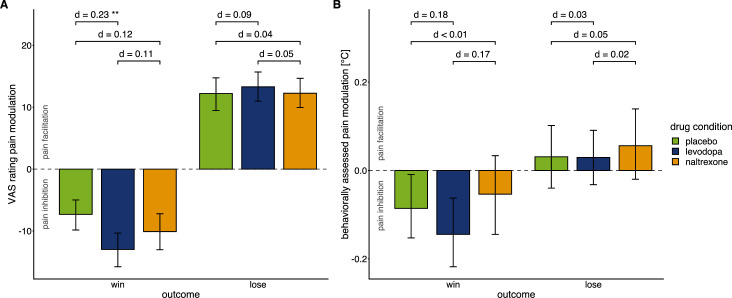

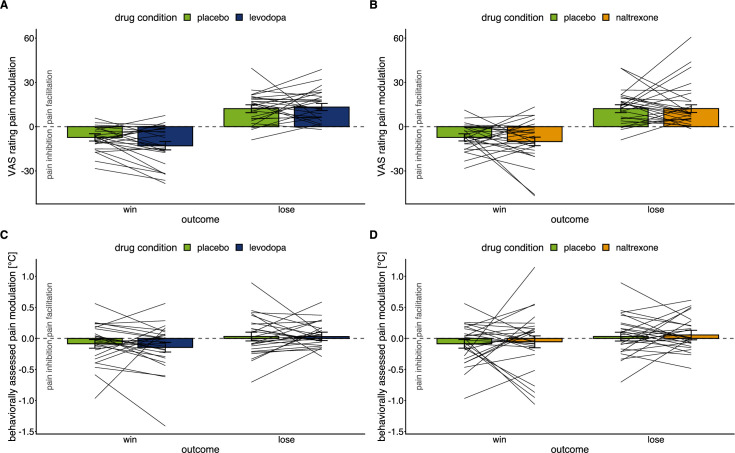

Figure 3. Effects of drug manipulation on endogenous pain modulation.

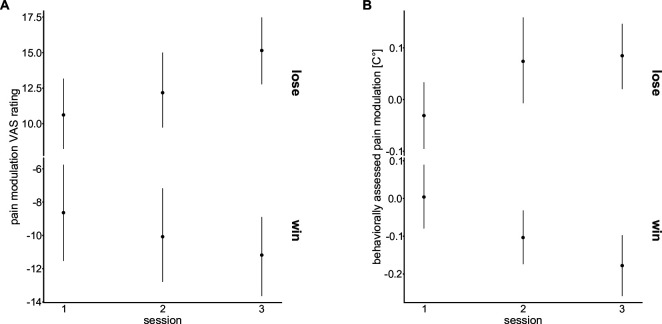

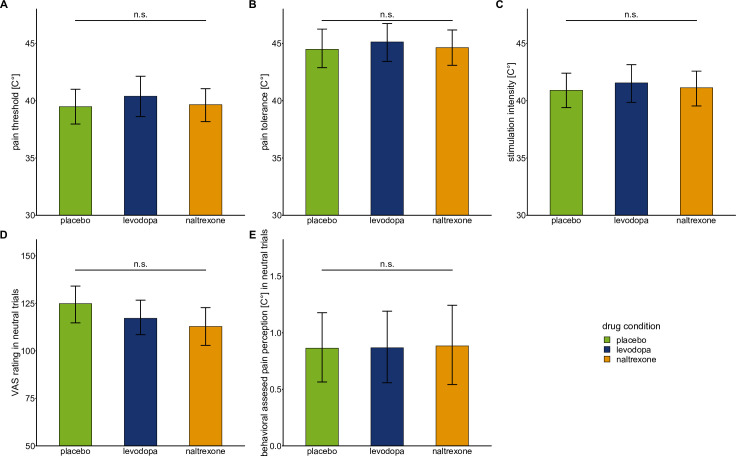

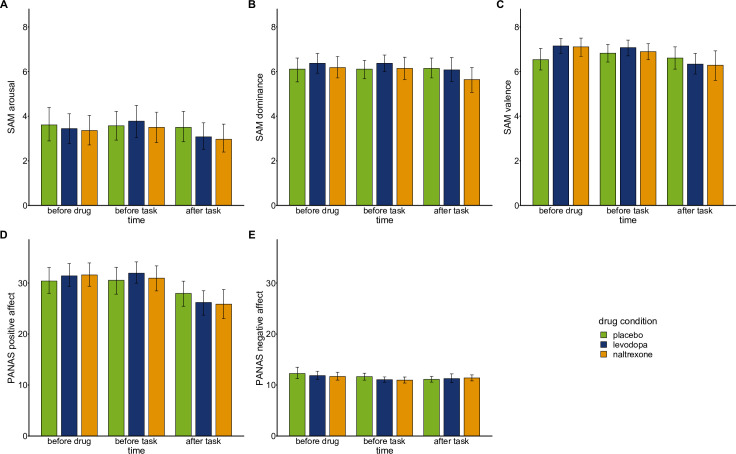

Effects of drug manipulation on endogenous pain modulation assessed by VAS ratings of pain intensity (A) and behaviorally assessed pain perception (B) after winning and losing in the wheel of fortune game, respectively (placebo: n=28, levodopa: n=27, naltrexone: n=28). Bars show group level means and error bars show 95% confidence interval of the group level mean. d indicates the standardized effect-size after controlling for random effects and residual variance. While the temporal order of sessions did affect pain modulation (Figure 3—figure supplement 1), measures of pain sensitivity, that were not experimentally manipulated (Figure 3—figure supplement 2), and measures of mood (Figure 3—figure supplement 3) did not significantly differ between drug conditions. For individual effects of the drug manipulations on endogenous pain modulation see Figure 3—figure supplement 4.