Abstract

Gun-related deaths and gun purchases were at record highs in 2020. In light of the COVID-19 pandemic, public protests against police violence, and a tense political environment, which may influence policy preferences, we aimed to understand the current state of support for gun policies in the U.S. We fielded a national public opinion survey in January 2019 and January 2021 using an online panel to measure support for 34 gun policies among U. S. adults. We compared support over time, by gun ownership status, and by political party affiliation. Most respondents supported 33 of the 34 gun regulations studied. Support for seven restrictive policies declined from 2019 to 2021, driven by reduced support among non-gun owners. Support declined for three permissive policies: allowing legal gun carriers to bring guns onto college campuses or K-12 schools and stand your ground laws. Public support for gun-related policies decreased from 2019 to 2021, driven by decreased support among Republicans and non-gun owners.

Keywords: Guns, Gun policy, Public opinion

1. Introduction

An estimated 45,000 people died from gun-related deaths in 2020, the highest single year count in over two decades (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, n.d.). While gun ownership has increased over time, the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, lockdowns, economic disruption, widespread protests against police violence, and a tense political environment likely contributed to record numbers of gun sales in 2020 (Tavernise, 2021). Millions of Americans buying guns in 2020 (20–30% of purchasers) were first-time gun owners (Crifasi et al., 2021; Miller et al., 2022).

Prior research has shown that many factors including race/ethnicity, gender, religion, and geography are associated with gun ownership and support for gun policies (Schaeffer, 2021; Oraka et al., 2019; Merino, 2018; O’Brien et al., 2013). Gun ownership is strongly linked to decreased support for more restrictive gun policies (Schaeffer, 2021). Political party affiliation is also associated with differences in support for gun regulations, though differences in support vary across policies (Schaeffer, 2021). A 2017 survey by the current authors found that only 8 of 24 gun policies had more than a 10-point gap in support between Republicans and Democrats (Barry et al., 2018).

In this nationally representative survey, we aim to understand the current state of support for 34 specific gun policies in the United States in 2021 and to assess changes in support by gun ownership status and political party affiliation between 2019 and 2021.

2. Methods

This analysis used two waves of the National Survey of Gun Policy of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health fielded January 2–28, 2019 and January 4–20, 2021 (Barry et al., 2019). Both waves were fielded using NORC’s AmeriSpeak Panel, a probability-based panel covering approximately 97% of U.S. households (NORC at the University of Chicago, 2022). Individuals age 18 years and older selected to participate could complete surveys online or by telephone (NORC at the University of Chicago, 2022). Both survey waves had high completion rates; 80% (n = 1680) and 78% (n = 2778) of invited participants completed the survey in 2019 and 2021 respectively.

All analyses used survey weights to account for known sample deviations and nonresponse (Appendix A). Both surveys oversampled gun owners, defined as a person who answered yes to both “Do you happen to have in your home or garage any guns or revolvers?” and “Do any of these guns personally belong to you?” Individuals were not considered gun owners if they answered yes to the first question but no to personally owning any of the guns. For analyses using political party affiliation, individuals were considered Democrats if they identified as “strong Democrat” or “not so strong Democrat”, Republicans if they responded as “strong Republican” or “not so strong Republican” and Independent otherwise (“lean Democrat,” “lean Republican,” or “don’t lean/Independent/None.”)

The 2019 and 2021 survey waves used identical question wording to measure support for 26 policies across eight categories: purchaser licensing and background checks, prohibiting certain persons from purchasing or owning guns indefinitely, assault weapons and largecapacity magazine bans, regulating licensed gun dealers, temporary firearm removal for high-risk individuals, concealed carry, prohibiting certain persons from purchasing or owning guns temporarily, and other policies. We examined differences in support for policies from 2019 to 2021 among the overall sample, among gun owners and non-gun owners, and among Democrats and Republicans. Next, we examined public support for eight policies measured for the first time in 2021 overall and by gun-ownership status. These included policies related to background checks, extending domestic-violence related prohibitions to dating partners, and directing federal funding to states that want to establish handgun licensing systems. Other policies measured for the first time focused on prohibiting behaviors such as bringing a gun into a government building, selling kits to build a gun at home, and open carry of a gun at a public demonstration or rally.

All measures of policy support were dichotomized from the original 5-point Likert scale with responses of “strongly favor” or “somewhat favor” indicating support compared to “neither favor nor oppose,” “somewhat oppose,” or “strongly oppose”. Pearson’s chi-squared tests were used to assess differences in support across waves, gun-ownership status, and political party affiliation. All analyses were completed using Stata 15 (StataCorp, 2017). Both survey waves were approved by the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health Institutional Review Board.

3. Results

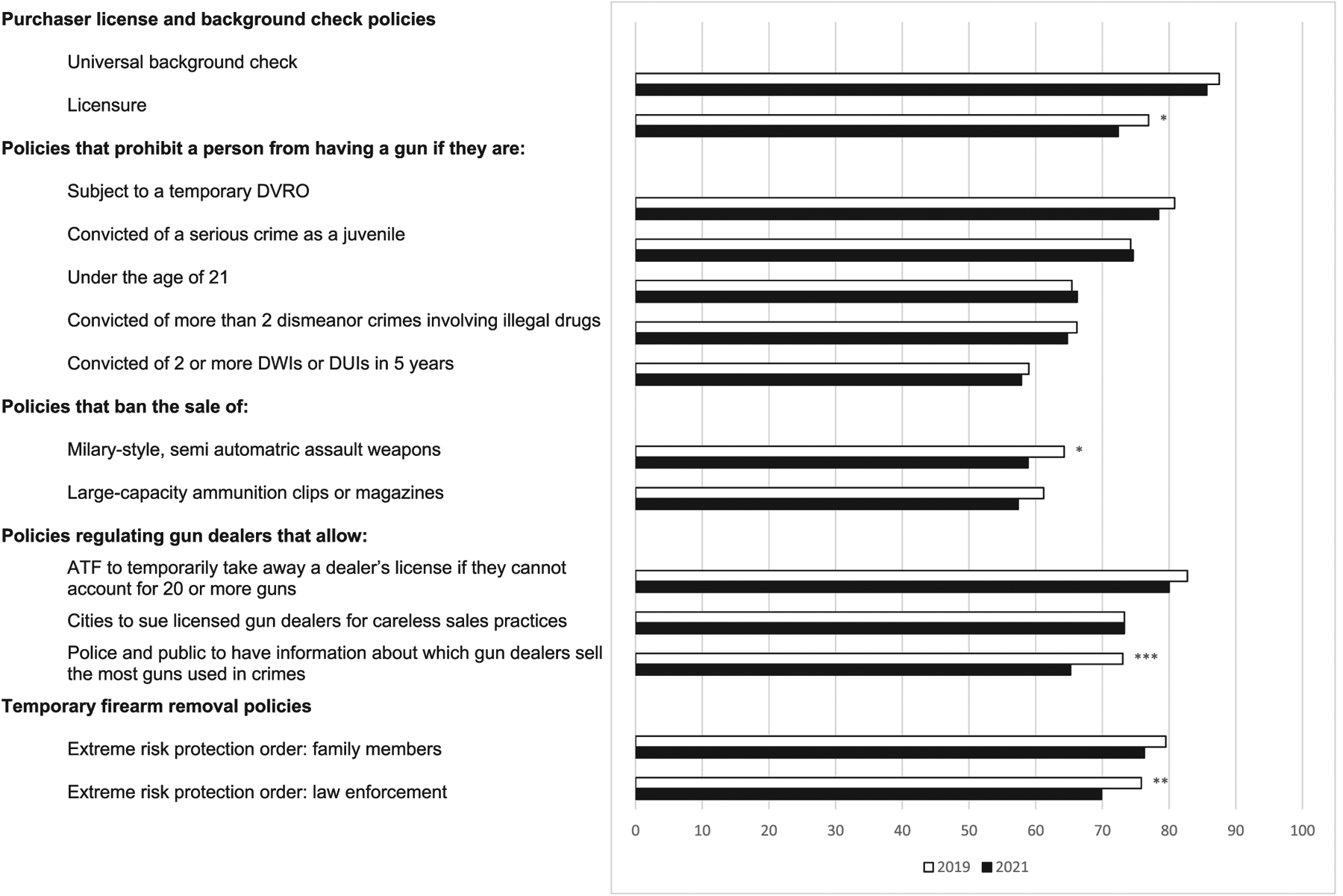

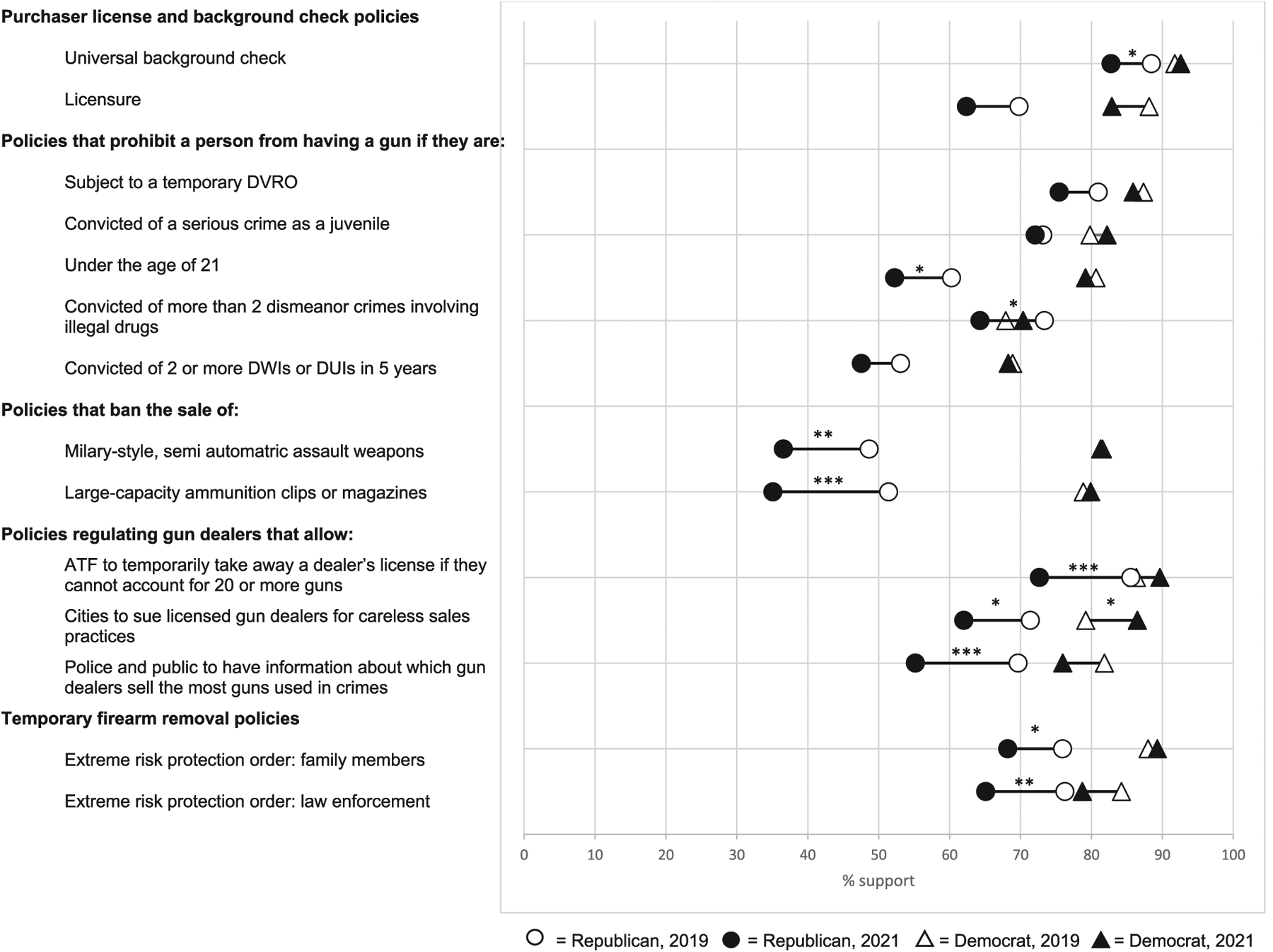

Of the 26 gun policies measured in both survey waves, public support declined significantly from 2019 to 2021 for three permissive policies, which would loosen restrictions on guns, and seven restrictive policies, which would increase restrictions on gun carrying and use, (Fig. 1). All declines in support were by <10 percentage points. The largest decreases in public support were for the three permissive policies: allowing a person who can legally carry a concealed gun to bring that gun onto a college or university campus (36% support in 2019 vs. 27% support in 2021); stand your ground (31% vs. 23%); and allowing a person who can legally carry a concealed gun to bring that gun onto school grounds for kindergarten through 12th grade schools (31% vs. 23%).

Fig. 1.

Percent of respondents who support different gun policies in 2019 and 2021.

Notes: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. ATF = Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives; DUI = driving under the influence; DVRO = domestic violence restraining order; DWI = driving while intoxicated; k-12 = kindergarden through 12th grade school.

Smaller but still statistically significant decreases in public support were observed for seven restrictive policies intended to curb gun violence: allowing the police and public to have information about which gun dealers sell the most guns used in crimes (73% in 2019 vs. 65% in 2021); requiring a safety test for a concealed carry license (81% vs. 73%); law enforcement-initiated extreme risk protection orders (76% vs. 70%); banning military-style, semi-automatic assault weapons (64% vs. 59%); requiring a person to be at least 21 years of age to own a semi-automatic rifle (73% vs. 68%); prohibiting a person from having a gun for 10 years if convicted of public display of a gun in a threatening manner, excluding self-defense (73% vs. 68%), and requiring licensure for purchase of a handgun (77% vs. 72%). Appendix B presents levels of support for all policies.

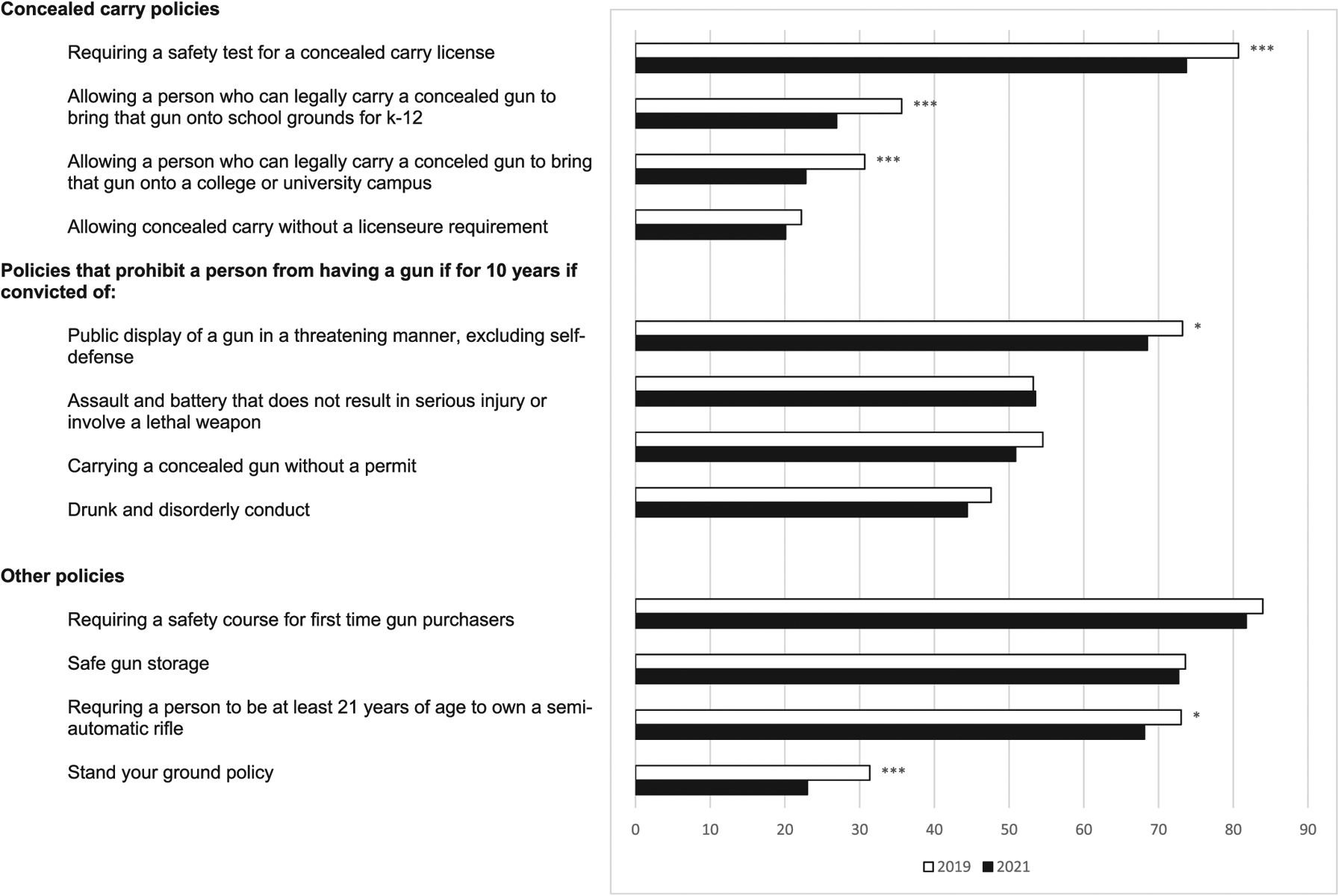

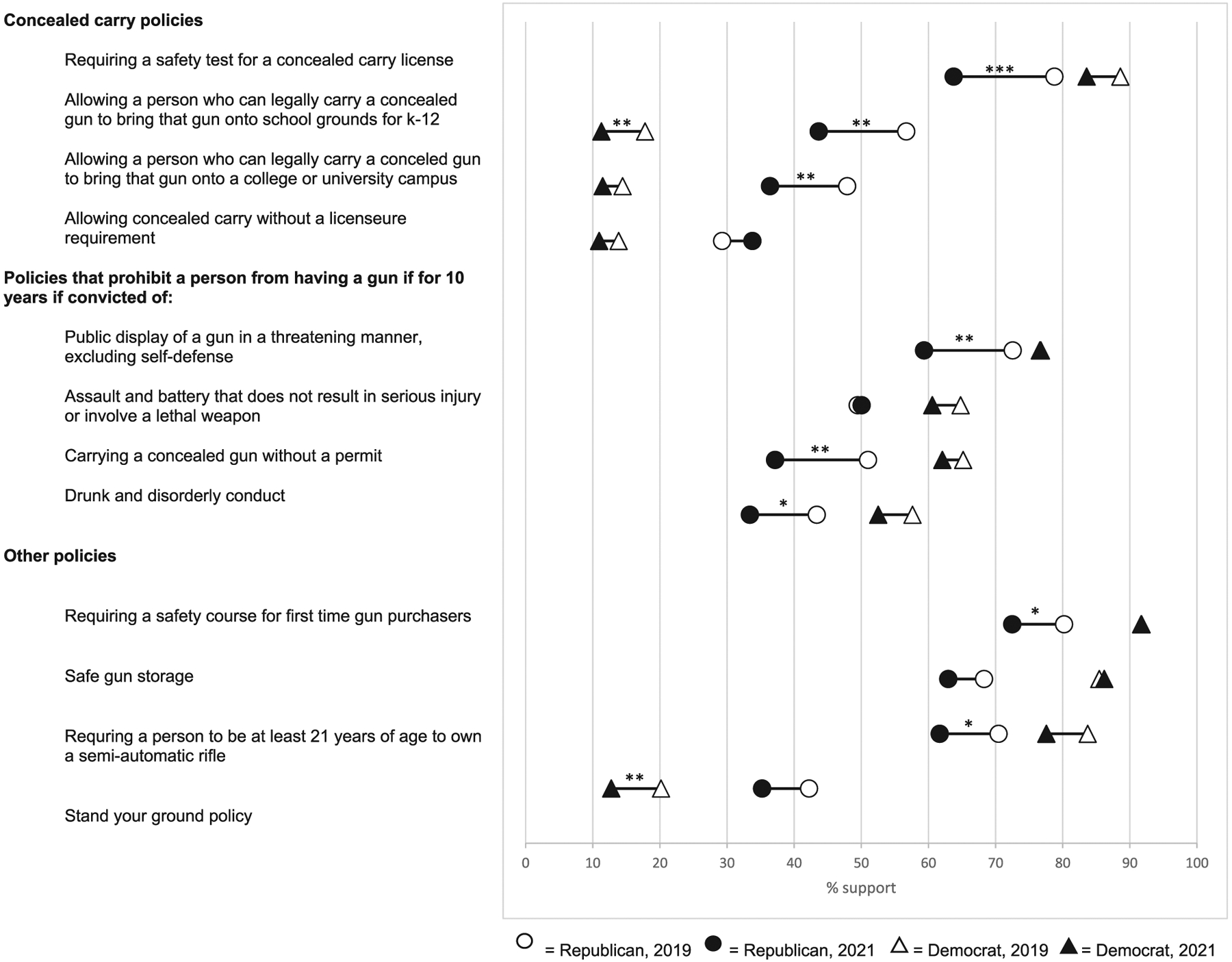

Changes in public support for gun policies were more common among non-gun owners than among gun owners (Fig. 2). There were statistically significant decreases in support among gun owners for only two policies – both of which would loosen restrictions on firearm carrying. Support among gun owners decreased by 10 percentage points for policies allowing a person who can legally carry a concealed gun to bring that gun onto a college or university campus (55% vs. 45%) and onto school grounds for kindergarten through 12th grade schools (47% vs. 37%).

Fig. 2.

Percent of respondents who support different gun policies in 2019 and 2021 by gun ownership status.

Notes: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. ATF = Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives; DUI = driving under the influence; DVRO = domestic violence restraining order; DWI = driving while intoxicated; k-12 = kindergarden through 12th grade school.

Among non-gun owners, there was significantly decreased support for three permissive gun policies and six restrictive policies. Support for three permissive policies decreased from 2019 to 2021 among non-gun owners: stand your ground policies (28% vs. 18%), allowing a person who can legally carry a concealed gun to bring that gun onto a college or university campus (29% vs. 20%) and onto school grounds for kindergarten through 12th grade schools (25% vs. 17%). Decreases in support among non-gun owners were also observed for six restrictive policies: allowing the police and public to have information about which gun dealers sell the most guns used in crimes (78% vs. 69%), requiring a safety test for a concealed carry license (83% vs. 77%), law enforcement-initiated extreme risk protection orders (80% vs. 73%), requiring a person to be at least 21 years of age to own a semi-automatic rifle (77% vs. 72%), allowing people to carry a concealed gun without a permit (59% vs. 54%), and banning the sale of military-style, semi-automatic assault weapons (72% vs. 67%). Appendix C presents levels of support by gun ownership in 2021.

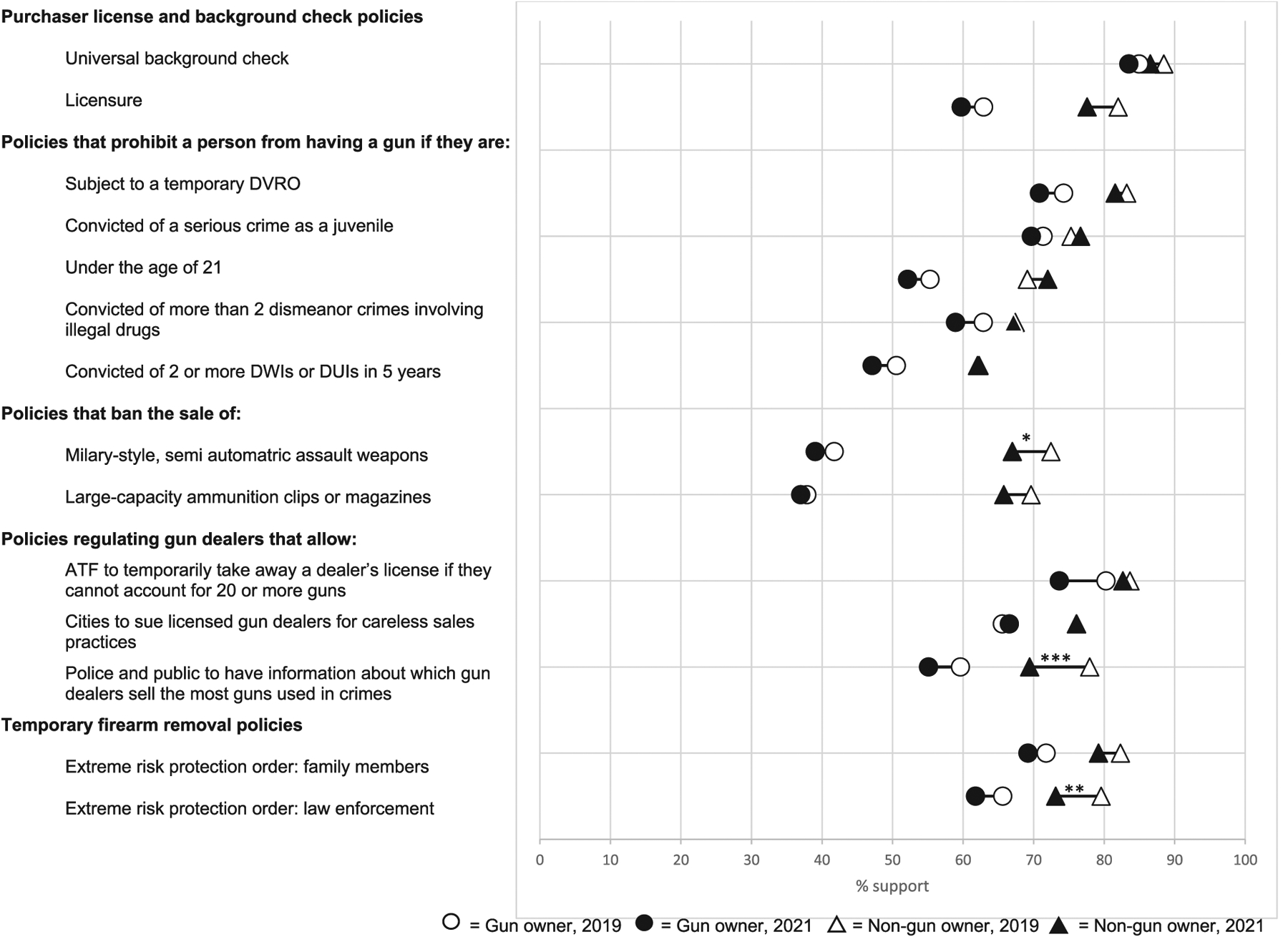

Changes in support for gun policies were more common among Republicans than Democrats (Fig. 3). Among Democrats, there was a significant increase in support from 2019 to 2021 for one restrictive policy: allowing cities to sue licensed gun dealers for careless sales practices (80% vs. 86%). There were significant decreases in support among Democrats for two permissive gun policies: allowing a person who can legally carry a concealed gun to bring that gun onto a college or university campus (18% vs. 11%) and stand your ground policies (20% vs. 13%).

Fig. 3.

Percent of respondents who support different gun policies in 2019 and 2021 by political party affiliation.

Notes: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. ATF = Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives; DUI = driving under the influence; DVRO = domestic violence restraining order; DWI = driving while intoxicated; k-12 = kindergarden through 12th grade school.

Among Republicans, there were significant decreases in support for 16 restrictive policies and 2 permissive policies. Support decreased among Republicans from 2019 to 2021 for the following restrictive policies: universal background checks (88% vs. 83%), prohibiting someone from having a handgun (60% vs. 52%) or a semi-automatic rifle (70% vs. 62%) if they are under the age of 21, prohibiting someone from having a gun if they are convicted of more than two misdemeanor crimes involving illegal drugs (73% vs. 64%), banning the sale of military-style, semi-automatic assault weapons (49% vs. 37%) or large capacity ammunition clips or magazines (51% vs. 35%), allowing the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) to temporarily take away a gun dealer’s license if they cannot account for 20 or more guns (86% vs. 73%), allowing cities to sue licensed gun dealers for careless sales practices (71% vs. 62%), allowing the police and public to have information about which gun dealers sell the most guns used in crimes (70% vs. 55%), extreme risk protection orders initiated by law enforcement (76% vs. 65%) or family members (76% vs. 68%), requiring a safety test for a concealed carry license (79% vs. 64%), prohibiting a person from having a gun for 10 years of convicted of public display of a gun in a threatening manner (73% vs. 59%), carrying a concealed gun without a permit (51% vs. 37%), or drunk and disorderly conduct (43% vs. 33%), and requiring a safety course for first-time gun purchasers (80% vs. 72%). Support among Republicans also decreased for two permissive policies: allowing a person who can legally carry a concealed gun to bring that gun onto a college or university campus (57% vs. 44%) or kindergarten through 12th grade school grounds (48% vs. 36%). Appendix D presents levels of support by party affiliation in 2021.

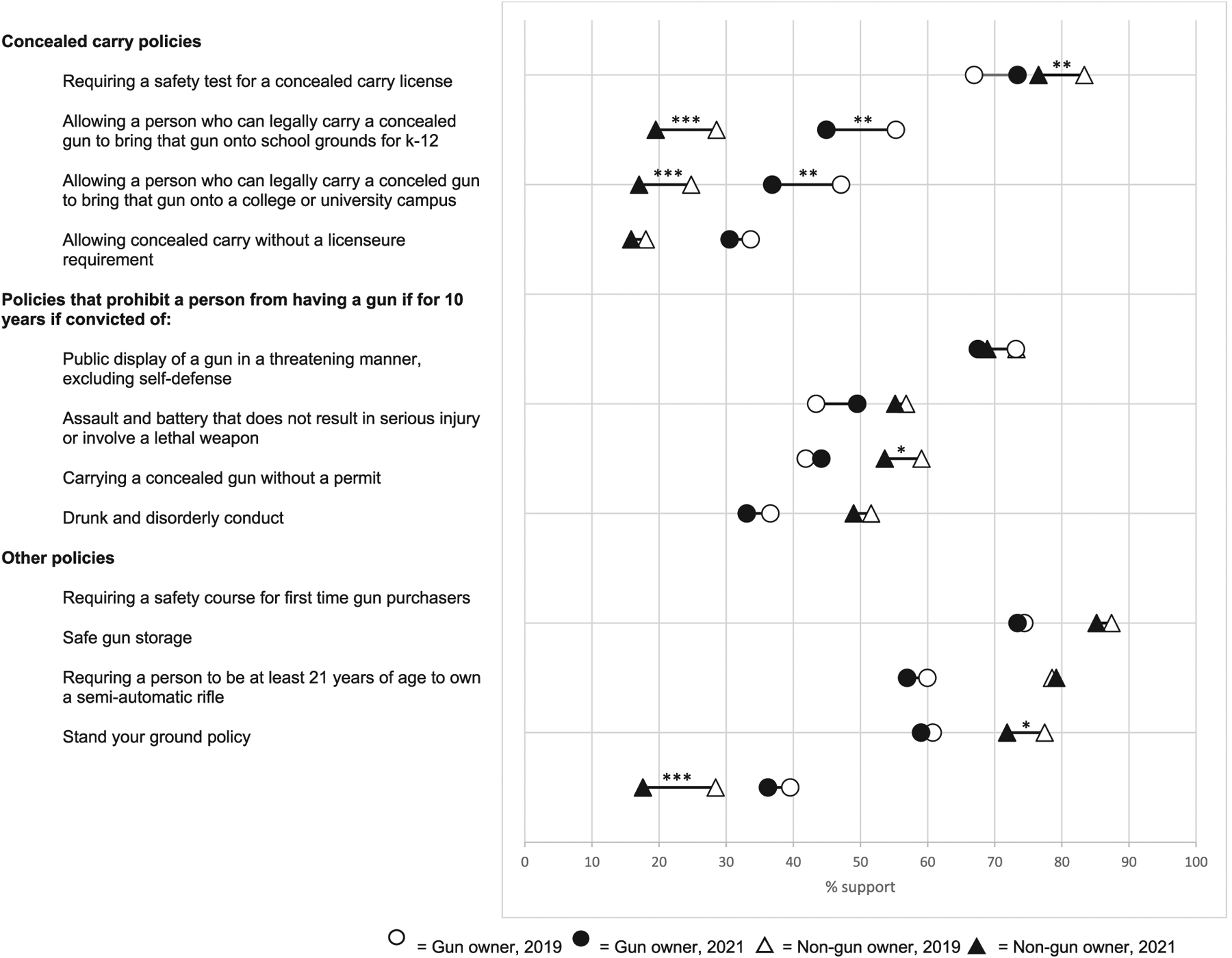

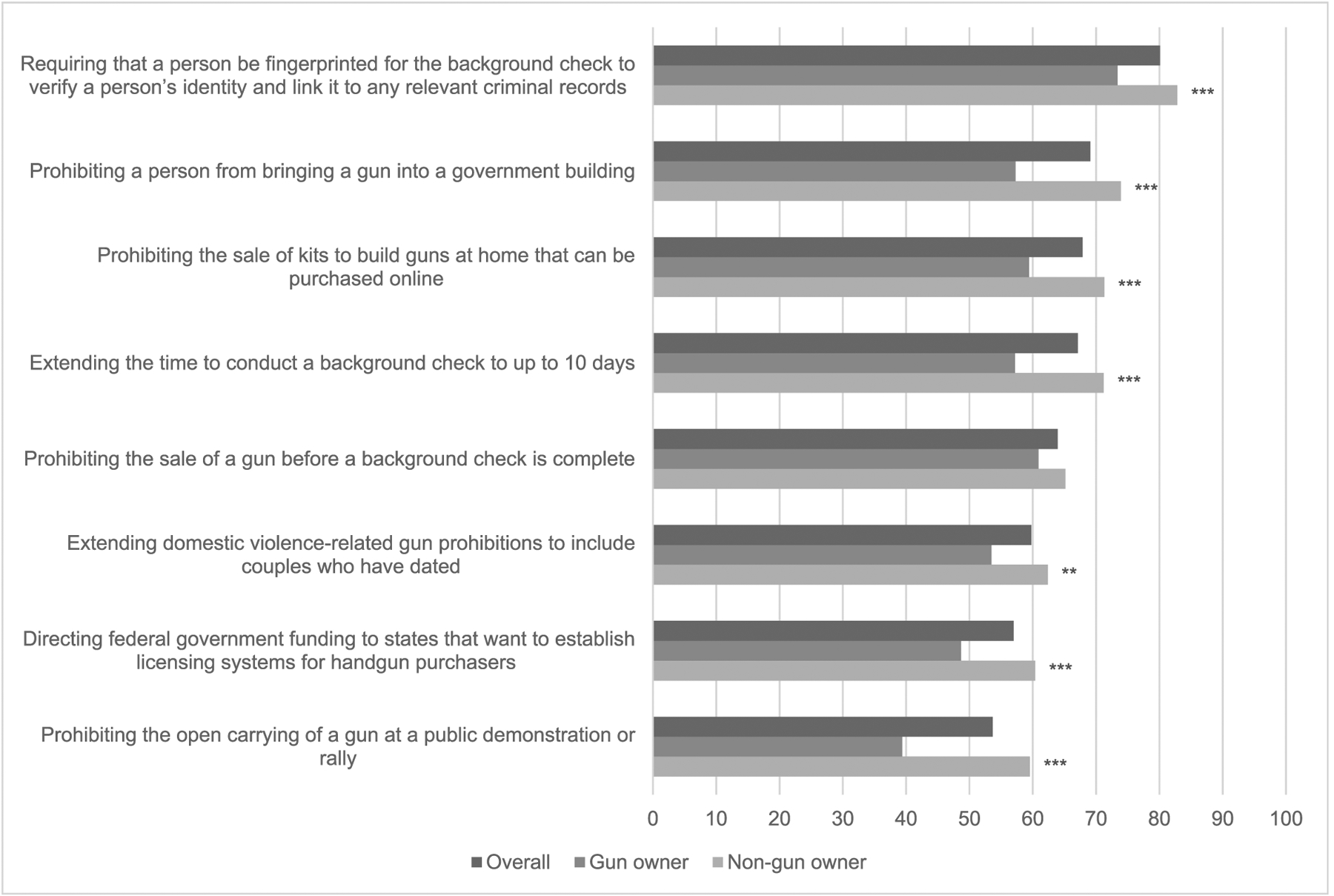

Fig. 4 shows public support for eight policies examined for the first time in 2021. The majority of respondents supported all eight restrictive policies including: requiring that a person be fingerprinted for the background check to verify their identity and link it to any relevant criminal records (80%), prohibiting a person from bringing a gun into a government building (70%), prohibiting the sale of kits to build guns at home that can be purchased online (68%), extending the time to conduct a background check to up to 10 days (67%), prohibiting the sale of a gun before a background check is complete (64%), extending domestic violence-related prohibitions to include couples who have dated (60%), directing federal government funding to states that want to establish licensing systems for handgun purchasers (57%), and prohibiting the open carrying of a gun at a public demonstration or rally (54%). Non-gun owners had significantly higher levels of support compared to gun owners for seven of the eight policies – all except prohibition of gun sales until a background check is complete (Appendix E and F).

Fig. 4.

Percent of respondents who support newly surveyed policies by gun ownership status, 2021.

Notes: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001.

4. Discussion

Most respondents to our 2021 national survey expressed support for broad range of policies related to guns and gun ownership. We found decreased support from 2019 to 2021 for three policies that would increase access to and carrying of firearms: allowing guns onto college campuses and K-12 school grounds and for stand your ground laws that expand legal justification for using lethal force. However, public support for seven policies intended to curb gun violence through gun regulations declined from 2019 to 2021. These changes were driven principally by decreased support among non-gun owners and Republicans.

The reasons for these trends are likely multi-faceted. Prior literature has shown associations between a lack of trust in the government, gun ownership, and skepticism of or opposition to gun safety reforms (Jiobu and Curry, 2001; De Angelis et al., 2017). In the wake of the social disruption due to the pandemic, lockdowns, job losses, acts of racialized police violence, protests, disputed elections, and violent insurrection, it is likely that some Americans – including non-gun owners – have experienced a decline in trust in government and lost faith in laws and law enforcement to keep them safe, resulting in decreased support, even for policies shown to prevent gun violence (Crifasi, 2018). For others, these events may have activated more partisan beliefs (e.g., as seen in the growth of the “Blue Lives Matter” retort to the “Black Lives Matter” movement),contributing to decreased support for gun regulations across the board as observed among Republicans in this survey (O’Brien et al., 2013; Hetherington and Weiler, 2018; Filindra and Kaplan, 2016).

Future research should examine determinants of attitudinal changes related to gun regulations in a longitudinal study that can determine causality and inflection points. Understanding why different groups hold or change their attitudes about various gun policies may help inform which messages or messengers and moments may be effective in increasing support for restrictive gun policies. Understanding drivers of attitudinal changes and the effectiveness of messaging on affecting policy support may be especially important as states may need to adapt their gun policies following recent, contradictory federal movement on the issue of gun policy. On June 25, 2022, following mass shootings in Buffalo, NY and Uvalde, TX, President Biden signed a bipartisan gun safety bill that includes incentives for states to adopt extreme risk protection order policies, closed the domestic violence dating loophole, and expanded background checks for gun sales to young adults ages 18–21 (S.2938 - 117th Congress (2021–2022): Bipartisan Safer Communities Act, n.d.). This law, however, follows a Supreme Court decision striking down a New York law that restricted concealed carry of guns (New York State Rifle and Pistol Association v. Bruen. 597 U.S, 2022). This decision not only established for the first time an individual right to “bear arms in public for self defense”, but also established a new test for determining the constitutionality of gun laws based on “text, history, and tradition.” (New York State Rifle and Pistol Association v. Bruen. 597 U.S, 2022)

This study should be viewed in light of its limitations. Online survey administration may be subject to sampling bias; however, the AmeriSpeak panel uses probability-based sampling and survey weights were used in all analyses to account for non-response and population characteristics (NORC at the University of Chicago, 2022; American Association for Public Opinion Research Standards Committee, 2010). While we compare support for policies from 2019 to 2021, both survey waves were cross-sectional, so we are unable to follow the same individuals over time. It is also beyond the scope of this study to examine drivers of changes within other sub-population groups. Finally, the attack on the U.S. Capitol occurred on January 6, 2021 while our survey was in the field. Most respondents (68%) completed the survey before January 6 and policy support was largely unassociated with when the survey was administered relative to January 6 (Appendix G).

5. Conclusion

Findings indicate that support for policies intended to reduce gun violence decreased from 2019 to 2021, driven by reductions in support among non-gun owners and Republicans. Future research should examine what determines attitudinal changes related to gun regulations.

Supplementary Material

Funding

This study was funded by the Bloomberg American Health Initiative and the Smart Family Foundation. Stone was supported by T32MH109436. Ward was supported by T32HD094687. The study sponsor did not play a role in study design, data analyses and interpretation, writing of the manuscript or the decision to submit this manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Elizabeth M. Stone: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. Cassandra K. Crifasi: Writing – review & editing. Julie A. Ward: Writing – review & editing. Jon S. Vernick: Writing – review & editing. Daniel W. Webster: Writing – review & editing. Emma E. McGinty: Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Colleen L. Barry: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2022.107314.

Data availability

The data that has been used is confidential.

References

- American Association for Public Opinion Research Standards Committee, 2010. AAPOR Report on Online Panels. Available at: http://www.aapor.org/Education-Resources/Reports/Report-on-Online-Panels.aspx. Accessed September 7, 2021.

- Barry CL, Webster DW, Stone E, Crifasi CK, Vernick JS, McGinty EE, 2018. Public support for gun violence prevention policies among gun owners and non–gun owners in 2017. Am. J. Public Health 108 (7), 878–881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry CL, Stone EM, Crifasi CK, Vernick JS, Webster DW, McGinty EE, 2019. Trends in public opinion on US gun laws: majorities of gun owners and non–gun owners support a range of measures. Health Aff. 38 (10), 1727–1734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS) [online]. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars. Accessed September 7, 2021.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Health Statistics. New CDC/NCHS Data Confirm Largest One-Year Increase in U.S. Homicide Rate in 2020. Available at: October 6, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/nchs_press_releases/2021/202110.htm. Accessed October 30, 2021.

- Crifasi C, 2018. Gun policy in the United States: evidence-based strategies to reduce gun violence. Appl. Health Econ. Health Policy 16 (5), 579–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crifasi CK, Ward JA, McGinty EE, Webster DW, Barry CL, 2021. Gun purchasing behaviours during the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, march to mid-July 2020. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Angelis J, Benz TA, Gillham P, 2017. Collective security, fear of crime, and support for concealed firearms on a university campus in the western United States. Crim. Justice Rev 42 (1), 77–94. [Google Scholar]

- Filindra A, Kaplan NJ, 2016. Racial resentment and whites’ gun policy preferences in contemporary America. Polit. Behav 38 (2), 255–275. [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington M, Weiler J, 2018. Prius or Pickup?: How the Answers to Four Simple Questions Explain America’s Great Divide. Houghton Mifflin. [Google Scholar]

- Jiobu RM, Curry TJ, 2001. Lack of confidence in the federal government and the ownership of firearms. Soc. Sci. Q 82 (1), 77–88. [Google Scholar]

- Merino SM, 2018. God and guns: examining religious influences on gun control attitudes in the United States. Religions. 9 (6), 189. [Google Scholar]

- Miller M, Zhang W, Azrael D, 2022. Firearm purchasing during the COVID-19 pandemic: results from the 2021 National Firearms Survey. Ann. Intern. Med 175 (2), 219–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen. 597 U.S. 2022.

- NORC at the University of Chicago, 2022. Technical Overview of the Amerispeak Panel NORC’s Probability-Based Household Panel. Available at: https://amerispeak.norc.org/Documents/Research/AmeriSpeak%20Technical%20Overview%202019%2002%2018.pdf. Accessed February 25, 2022.13.

- O’Brien K, Forrest W, Lynott D, Daly M, 2013. Racism, gun ownership and gun control: biased attitudes in US whites may influence policy decisions. PLoS One 8 (10), e77552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oraka E, Thummalapally S, Anderson L, Burgess T, Seibert F, Strasser S, 2019. A cross-sectional examination of US gun ownership and support for gun control measures: sociodemographic, geographic, and political associations explored. Prev. Med 123, 179–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- S.2938 - 117th Congress (2021 – 2022): Bipartisan Safer Communities Act. Schaeffer K, 2021. Key Facts about Americans and Guns. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/09/13/key-facts-about-americans-and-guns/. Accessed July 8, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp, 2017. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX. [Google Scholar]

- Tavernise S, May 31, 2021. An Arms Race in America: Gun Buying Spiked During the Pandemic. It’s Still Up. The New York Times. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that has been used is confidential.