Abstract

Purpose:

New oral nicotine products (ONPs), often advertised as “tobacco-free” (i.e., pouches, gum, lozenges, gummies), come in nontobacco flavors appealing to adolescents. It is unknown how adolescent willingness to use ONPs differs by product type and flavor, and whether sociodemographic disparities exist.

Methods:

Adolescent never tobacco product users (n = 1, 289) in ninth or 10th grade from 11 high schools in Southern California were surveyed in fall 2021 about ever and past 6-month use of ONPs and sociodemographic characteristics. Adolescents were randomized to view five different ONPs in either fruit or mint flavor, and asked to rate their willingness to use each product. Multivariable logistic random effect-repeated measures regression examined associations of product type, flavor, and sociodemographic characteristics with any willingness to use ONPs.

Results:

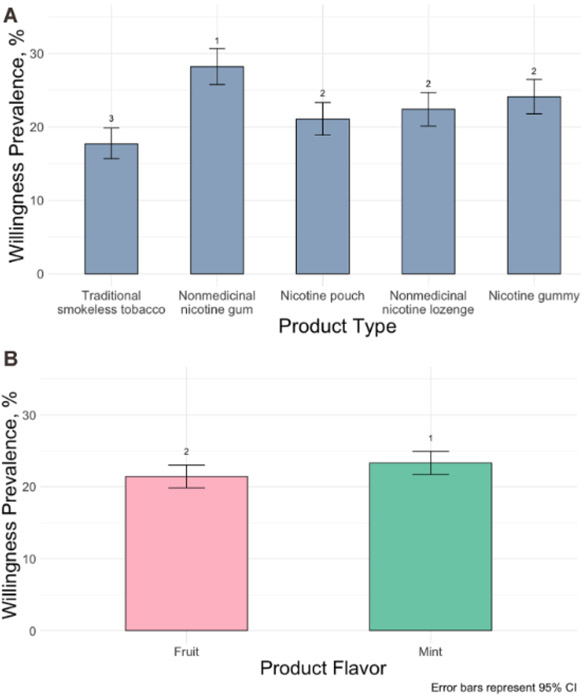

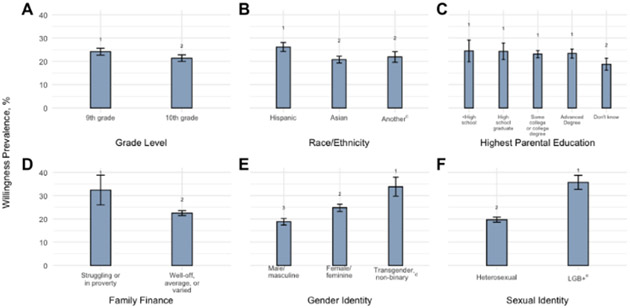

Compared to traditional smokeless tobacco (willingness = 17.8%), adolescents reported greater willingness to use ONPs (gum, 28.2%; pouches, 21.1%; lozenge, 22.4%; gummies, 24.1%); adjusted odd ratios [aORs] 1.25–1.84; p-values<.001). Mint flavor (23.3%) compared to fruit flavor (21.4%), significantly increased odds of willingness to use across all ONPs (aOR [95%CI] = 1.15 [1.05, 1.26], p = .004). Younger adolescents (ninth, 24.2% vs. 10th grade, 21.4%) and LGBTQ+ (34.2%) versus heterosexual (19.7%) and cisgender (18.8%) adolescents were more willing to use these products.

Discussion:

Adolescents reported greater willingness to use new ONPs compared to traditional smokeless tobacco. Adolescents who were younger (vs. older adolescents) or identified as LGBTQ+(vs. heterosexual and cisgender) were more willing to use new ONPs. Efforts to monitor adolescents’ willingness to use and actual use of these products are warranted.

Keywords: Adolescents, Oral nicotine products

A growing sector of new oral nicotine products (ONPs) (i.e., nicotine pouches, nontherapeutic gums, nontherapeutic lozenges, and gummies) are marketed and sold in the United States [1]. These products constitute a new category that differs from existing therapeutic oral nicotine and tobacco products and possesses unique characteristics (e.g., appealing flavors) that might attract adolescent users. Although some novel ONPs may have similar ingredients to therapeutic ONPs, they are sold and federally regulated as recreational (nontherapeutic) tobacco products and are available in a wider variety of flavors (e.g., ‘cherry bomb’) and formulations (e.g., gummies). Unlike existing recreational oral tobacco products (e.g., smokeless chewing tobacco), novel ONPs possess sleek packaging, do not use tobacco leaves, and do not use the term tobacco in their marketing (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Pictures oral products displayed participants in the experiment

It is unknown whether novel ONPs appeal to adolescents who have never used nicotine, which particular products might be most appealing, and if specific demographic groups are disproportionately susceptible to using these products. Use of traditional smokeless oral tobacco among adolescents and young adults has decreased over the past decade [2-4], with 3.6% of US high school students in 2021 [5] and 0.6% of California high school students in 2019–2020 [6] reporting current smokeless tobacco use. In tandem, US advertising expenditures on smokeless tobacco have steadily decreased since 2016, totaling $567,262,000 in 2020 [7]. While these trends are promising for public health, novel ONPs may be perceived more positively by adolescents than traditional smokeless tobacco due to their adolescent-friendly features (e.g., “tobacco-free” marketing moniker, discreetness, variety of flavors). Recent findings from the 2021 National Youth Tobacco Survey (NYTS) found that 1.9% of adolescents reported ever using of nicotine pouches, and less than 1% (0.08%) were current nicotine pouch users [5]. Evidence of whether adolescents are more likely to use novel ONPs compared to traditional smokeless tobacco would provide an empirical benchmark to guide various regulatory decisions about these products. If novel ONPs disproportionately appeal to certain demographic subpopulations, regulatory approaches to these products might take into account the implications for health disparities. Additionally, evidence on whether certain flavors of novel ONPs appeal to adolescents could further inform which flavors should be restricted or allowed to be marketed. The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently authorized marketing and sales of nicotine gum and lozenges manufactured by Altria Group, Inc—the maker of Marlboro brand cigarettes—in mint flavors (i.e., Verve Discs Blue Mint, Verve Discs Green Mint, Verve Chews Blue Mint, and Verve Chews Green Mint) [8]. More recently, the FDA issued a warning letter to the manufacturer VPR Brands LP (doing business as, “Krave Nic”), which markets gummies that have 1 milligram (mg) of nicotine each and are available in three flavors—Blueraz, Cherry Bomb, and Pineapple [9]. Use of any nicotine during adolescence is concerning given the harmful effects of nicotine on the developing brain [10-13]. Several manufacturers of novel nicotine pouches, gums, and lozenges have applied to the FDA to market their products in mint flavors as well as various unique fruit flavors (e.g., blue-raspberry, pomegranate) and are awaiting FDA regulatory decisions [14,15]. In addition to FDA regulatory decisions, many states and localities have restricted the sale of flavored tobacco products [16]. Appeal of flavored ONPs to adolescents should be taken into account at the state and local levels.

Use of new ONPs among adolescents is a growing problem. Our research recently found that adolescents were more likely to have used novel ONPs (e.g., gums, gummies) than most other nicotine/tobacco products, including combustible cigarettes [17]. To our knowledge, research has not yet examined adolescents’ willingness to use novel ONPs in comparison to traditional smokeless tobacco. The current study, among adolescents who reported never-use of any tobacco/nicotine product, examined self-reported willingness to use several types of commercially marketed oral nicotine and tobacco products. We hypothesized that adolescents would report greater willingness to use novel nicotine gums, lozenges, and gummies compared to traditional oral smokeless tobacco and higher intention to use fruit-versus mint-flavored oral tobacco products. We also examined sociodemographic correlates of willingness to use oral nicotine products.

Methods

Study sample and procedures

Public high schools in the Southern California region (i.e., Los Angeles, Riverside, San Bernardino, Orange, and Imperial counties) were approached about participating in a longitudinal cohort study on adolescent health behavior. Approximately 70 schools were approached about participating in the study to maximize diversity in sociodemographic characteristics of the sample, with a focus on recruiting schools representing adolescents from a wide variety of racial/ethnic backgrounds, socio-economic statuses, and suburban/urban areas. A total of 11 schools in eight school districts agreed to participate in the study. Recruitment of ninth graders from these 11 schools was conducted in two waves. Participation involved completing surveys semiannually. The survey reported here was administered September–December 2021.

Students completed in-classroom surveys collected on-site at their respective schools via self-administered computerized assessments. Students absent during data collection days were sent a link to the survey and invited to complete the electronic survey remotely outside of their class time (49.0% of students in the analytic sample). Among adolescents who completed the oral nicotine and tobacco use measures (N = 1,393), ever-users of any nicotine or tobacco product (i.e., combustible cigarettes, e-cigarettes, hookah, cigars/cigarillos, ONPs) were excluded from analyses (n = 104), leaving an analytic sample of 1,289 participants.

Ethics statement

The study was approved by the University of Southern California Institutional Review Board. Written parental consent and adolescent assent were obtained prior to data collection.

Measures

Willingness to use oral nicotine products (ONPs).

The FDA provides guidance regarding tobacco product perception and intention methodologies for assessing intention to use novel products [18], which we applied here. Participants received the following text: “Below are various types of nicotine products, including ones you can eat, suck on, or chew. We’re curious about whether you would try using any of them if you were offered them by a friend or someone you trust.” Next, participants were displayed pictures of each of the following product types: nontherapeutic nicotine gum, nicotine pouch, nontherapeutic nicotine lozenge, nicotine gummy, and smokeless tobacco (see Figure 1). Pictures were taken from mass-marketed manufacturer and distributor websites and were embedded as static images within the survey. Below the picture of each product, the question, “Would you use this product?” was displayed with the following responses: never, most likely not, probably not, not sure, maybe, probably yes, most likely yes, absolutely. Following previous research [19-21], responses were recoded into a dichotomous outcome separating non-willing (never [ = 0]) versus willing (all other responses [ = 1]). To examine differences in willingness to use each product type and the effect product flavor may have on willingness to use each product, participants were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to view each of the oral products in either a mint or fruit flavor, except for the gummy product which is only available in fruit flavors (participants randomized to either “Cherry Bomb” or “BlueRaz” gummy).

Sociodemographic characteristics

Adolescents self-reported sexual identity (heterosexual, asexual, bisexual, gay, lesbian, pansexual, queer, questioning, prefer not to disclose), gender identity (male/masculine, female/feminine, transgender male, transgender female, gender variant/nonbinary, another gender, prefer not to disclose), race/ethnicity (Hispanic, Non-Hispanic: American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, Black/African American, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, White, multiracial, another race, not reported), and highest parental/caregiver education (eighth grade or less, less than high school, high school graduate, some college, college graduate, advanced degree, do not know). Family finances were assessed using the following item: “Think about your family when you were growing up, from birth to age 16. Would you say your family during that time was…,” with the following corresponding response options: “Pretty well off financially,” “About average,” “Financially struggling or in poverty,” or “It varied.” All variables were assessed with investigator-defined, forced-choice, self-reported items.

For descriptive purposes, we reported frequencies for each raw response category. Due to small cell sizes for particular response categories, for primary analyses we collapsed some responses and then recoded the following variables: family finances (financially struggling or in poverty vs. all other categories), highest parental education (less than high school, high school graduate, some college or college degree, advanced degree, or do not know), race/ethnicity (Hispanic, Non-Hispanic, Asian, all other races [i.e., American Indian/Alaska Native, Black/African American, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, White, multiethnic/multiracial, and another]), gender identity (male/masculine, female/feminine, transgender/non-binary), and sexual identity (heterosexual, all other sexual identities [LGB+]).

Data analytic plan.

Using χ2 tests, we examined differences in average prevalence of willingness to use new ONPs, stratified by product type, flavor, and sociodemographic characteristics (see Figures 2 and 3). In the main analysis, mixed model logistic regression including random effects to allow for both within and between-subject factors was used to test the association of product type, flavor, and demographic variables with odds of willingness to use (yes/no). Using outcome data for use willingness for all five products, we first tested a multivariable model in which within-subject (i.e., product type [smokeless tobacco as referent category]) and between-subject (i.e., sociodemographic variables) were simultaneous regressors. Next, interaction terms were separately added in subsequent models to test whether associations of flavor type with use willingness differed between mint and fruit flavors (product type × flavor) and whether associations of product type or flavor with use willingness differed by sociodemographic characteristics (product type × sociodemographic and flavor × sociodemographic). Analyses were tested in Mplus version eight using multilevel random effects [22]. Product type and flavor were nested within adolescents via two-level hierarchical modeling, and the effect of adolescent clustering within schools was adjusted by the complex design option [23]. Missing data on demographics were managed with full information maximum likelihood estimation. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated with statistical significance set at p < .05 (2-tailed). Benjamini-Hochberg multiple-testing corrections were applied to control the false-discovery rate at 0.05 [24].

Figure 2.

Willingness to use new oral nicotine products by product type and flavora,b. (A) is willingness prevalence by oral nicotine product type. (B) is willingness prevalence by product flavor (i.e., fruit or mint).

Note.a Analytic sample N=1289.b Diflerences calculated using the χ2 test. Groups not sharing numerals are significantly different in Bonferroni-corrected post-hoc pairwise contrasts. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 3.

Prevalence of willingness to use oral nicotine products by sociodemographic characteristics.a,b.

Note.a Analytic sample N = 1,289. b Differences calculated using the χ2 test. Groups not sharing numerals are significantly different in Bonferroni-corrected post hoc pairwise contrasts.c The “Another Race/Ethnicity” race/ethnicity category includes American Indian/Alaska Native, Black/African American, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, White, multiethnic/multiracial, and other. d The “transgender, nonbinary” category includes transgender male, transgender female, gender variant/nonbinary, or other categories. e The “LGB+” category includes lesbian, gay, bisexual, asexual, queer, pansexual, and questioning. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. (A-F) represent ONP willingness prevalence across different sociodemographic characteristics.

Results

Study sample

Demographic characteristics of the analytic sample of 1,289 never-users of combustible cigarettes, e-cigarettes, hookah, cigars/cigarillos, or ONPs are reported in Table 1. The sample included about half ninth grade and half 10th grade students and was demographically diverse (31.6% Hispanic, 48.5% Asian, 10.4% multiracial, 5.1% transgender/nonbinary identity, 15.6% nonheterosexual identity, 24% with neither parent with a college degree).

Table 1.

Characteristics of study sample of never nicotine/tobacco usersa

| Variablesb | n (%) |

|---|---|

| High school grade | |

| 9th grade | 630 (48.9) |

| 10th grade | 659 (51.1) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Hispanic | 405 (31.6) |

| Asian | 621 (48.5) |

| White | 84 (6.6) |

| Multiracial | 133 (10.4) |

| Another race/ethnicityc | 37 (2.9) |

| Gender identity | |

| Female or feminine | 576 (44.9) |

| Male or masculine | 600 (46.8) |

| Transgender or nonbinaryd | 65 (5.1) |

| Prefer not to disclose | 42 (3.3) |

| Sexual identity | |

| Straight or heterosexual | 942 (73.8) |

| LGB+e | 199 (15.6) |

| Questioning or unsure | 72 (5.6) |

| Prefer not to disclose | 63 (4.9) |

| Highest parental education | |

| Some high school or less | 67 (5.2) |

| High school graduate | 111 (8.7) |

| Some college | 130 (10.1) |

| College graduate | 438 (34.1) |

| Advanced degree | 357 (27.8) |

| Do not know | 180 (14.0) |

| Family finances | |

| Pretty well off financially | 374 (29.2) |

| About average | 710 (55.5) |

| Financially struggling or in poverty | 42 (3.3) |

| It varied | 153 (12.0) |

N = 1,298 never-users of combustible cigarettes, e-cigarettes, hookah, cigars/cigarillos, or oral nicotine.

Available data Ns = 1,276–1.233

Includes American Indian/Alaska Native, Black/African American, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, and “another” categories.

Includes transgender male, transgender female, gender variant/nonbinary, and “another” categories.

Includes asexual, bisexual, gay, lesbian, pansexual, queer, and “another” categories.

Associations of product type, flavor, and sociodemographic factors with willingness to use ONPs

Before the primary regression model was examined, we tested bivariate associations among all independent variables to check for the multicollinearity violation [25]. We examined Cramer’s V measuring the strength of association or dependency between two categorical variables. Cramer’s V estimates of all bivariate associations ranged from 0.03 (grade - financial status) to 0.46 (gender identity-sexual identity), which showed weak to moderate associations. No strong effect size (>0.6) was detected, and therefore our primary regression model did not have the multicollinearity issue.

In the multivariable regression model 1 (Table 2, Model 1) including five product types and all sociodemographic covariates as simultaneous main effects regressors, product type was associated with willingness to use ONPs. Compared to smokeless tobacco (17.8%), willingness to use nontherapeutic gum (28.2%; adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 95%CI = 1.84 [1.68, 2.02]), pouches (21.1%; AOR [95%CI] = 1.25 [1.13,1.38]), nontherapeutic lozenges (22.4%; AOR [95%CI] = 1.34 [1.22, 1.46]), and gummies (24.1%; AOR [95%CI] = 1.47 [1.34, 1.62]) were significantly higher (p-values<.001; see Figure 2A). Collapsed across the five products, high school grade, gender identity, and sexual identity were significantly associated with increased willingness to use any oral nicotine product (see Table 2). Adolescents in 10th grade (21.4%) versus ninth grade (24.2%) had decreased odds of willingness to use ONPs (AOR [95%CI] = 0.72 [0.55, 0.92], p = .004). Also, students reporting their gender identity as female/feminine (24.8%; AOR [95%CI] = 1.36 [1.03, 1.80], p = .02) or transgender/nonbinary (33.8%; AOR [95%CI] = 1.64 [1.18, 2.95], p = .004) had greater odds of willingness to use ONPs than cisgender male adolescents (18.8%). Compared to heterosexual adolescents (19.7%), LGB + adolescents (35.7%) had greater odds of willingness to use ONPs (AOR [95%CI] = 1.89 [1.30, 2.75], p < .001). No significant associations were detected for race/ethnicity, highest parental education, or family finances after adjusting for other covariates, though Hispanic ethnicity and financially struggling were associated with greater odds of willingness to use ONPs in unadjusted analyses (Figure 3). Each of the demographic and product type associations was replicated in a second model (Table 2, Model 2) that excluded gummies data and additionally included the flavor variable. The model also found that mint flavor significantly increased odds of use intention compared to fruit flavor (23.3% vs. 21.4% presented in Figure 2B; AOR [95%CI] = 1.15 [1.05, 1.26], p = .004).

Table 2.

Associations of product type, flavor, and sociodemographic factors with willingness to use oral nicotine products

| Regressors | Model 1a,b |

Model 2a,b |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted OR (95%CI) | p-value | Adjusted OR (95%CI) | p-value | |

| Product type | ||||

| Traditional smokeless tobacco | REF | – | REF | – |

| Nonmedicinal nicotine gum | 1.84 (1.68, 2.02) | <.001g | 1.84 (1.67, 2.03) | <.001g |

| Nicotine pouches | 1.25 (1.13, 1.38) | <.001g | 1.25 (1.12, 1.38) | <.001g |

| Nonmedicinal nicotine lozenges | 1.34 (1.22. 1.46) | <.001g | 1.34 (1.22, 1.47) | <.001g |

| Nicotine gummiesc | 1.47 (1.34, 1.62) | <.001g | Not included | – |

| Flavor | ||||

| Fruit | Not included | – | REF | – |

| Mint | Not included | – | 1.15 (1.05, 1.26) | .004g |

| High school grade | ||||

| 9th grade | REF | – | REF | – |

| 10th grade | 0.72 (0.55, 0.92) | .004g | 0.74 (0.56, 0.94) | .01g |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic | 1.30 (0.90, 1.88) | .16 | 1.32 (0.92, 1.90) | .13 |

| Asian | 0.93 (0.66, 1.34} | .73 | 0.94 (0.66, 1.34) | .74 |

| Another race/ethnicityd | REF | – | REF | – |

| Highest parental education | ||||

| <High school | 1.27 (0.74, 2.21) | .38 | 1.33 (0.77, 2.32) | .29 |

| High school graduate | 1.19 (0.73, 1.93) | .49 | 1.18 (0.72, 1.91) | .50 |

| Some college or college degree | REF | – | REF | – |

| Advanced degree | 1.02 (0.74, 1.39) | .91 | 1.01 (0.74, 1.37) | .96 |

| Do not know | 0.86 (0.57, 1.31) | .49 | 0.93 (0.62, 1.42) | .65 |

| Family finances | ||||

| Struggling or in poverty | 1.10 (0.51, 2.34) | .81 | 1.13 (0.52, 2.46) | .73 |

| Well-off, average, or varied | REF | – | REF | – |

| Gender identity | ||||

| Male/masculine | REF | – | REF | – |

| Female/feminine | 1.36 (1.03, 1.80) | .02g | 1.36 (1.03, 1.81) | .02g |

| Transgender or nonbinarye | 1.64 (1.18, 2.95) | .004g | 1.63 (1.17, 2.94) | .008g |

| Sexual identity | ||||

| Heterosexual | REF | – | REF | – |

| LCB+f | 1.89 (1.30, 2.75) | <.001g | 1.88 (1.29, 2.74) | .001g |

OR, odds ratio; 95%CI, 95% confidence interval.

Analytic sample N = 1,289 (tobacco nonusers who completed the experimental paradigm).

Binary logistic mixed random effect-repeated measures regression modeling (outcome: willingness to use [Yes/No]) includes all regressors simultaneously. School-level clustering effects were adjusted using the complex analysis function.

Nicotine gummies product type includes candy flavor only and therefore Model 1 did not include flavor variable. In Model 2 which included the flavor variable, data observations for nicotine gummies were excluded.

The “Another Race/Ethnicity” race/ethnicity category includes American Indian/Alaska Native, Black/African American, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, White, multiethnic/multiracial, and another.

The “Transgender or nonbinary” category includes transgender male, transgender female, gender variant/nonbinary, or another categories.

The “LGB+” category includes lesbian, gay, bisexual, asexual, queer, pansexual, and questioning.

p-values were statistically significant after Benjamini-Hochberg corrections for multiple testing to control false-discovery rate at .05 (based on 2-tailed corrected p-value).

Interaction tests

The association of product type with willingness to use ONPs was not moderated by flavor (product type × flavor, p = .25; Table 3). Omnibus tests of whether the effect of product type and flavor on use intention differed by each sociodemographic factor were also not significant (product type × sociodemographic and flavor × sociodemographic characteristics p-values ≥ .07).

Table 3.

Interaction effects among study variables on willingness to use

| Interaction terms | Model 1a,b,c |

Model 2a,b,c |

|---|---|---|

| p-valued | p valued | |

| Product type × flavor | NA | .25 |

| Product type interaction terms | ||

| Product type × high school grade | .43 | .34 |

| Product type × race/ethnicity | .12 | .09 |

| Product type × highest parental education | .07 | .10 |

| Product type × family finances | .09 | .14 |

| Product type × gender identity | .20 | .12 |

| Product type × sexual identity | .18 | .13 |

| Flavor interaction terms | ||

| Flavor × high school grade | NA | .98 |

| Flavor × race/ethnicity | NA | .51 |

| Flavor × highest parental education | NA | .83 |

| Flavor × family finances | NA | .37 |

| Flavor × gender identity | NA | .64 |

| Flavor × sexual identity | NA | .72 |

NA, not assessed.

Analytic sample N = 1,289.

Binary logistic random effect-repeated measures mixed regression modeling (outcome: willingness to use [Yes/No]) includes all regressors presented in Table 2 simultaneously. School-level clustering effects were adjusted using the complex analysis function.

Each interaction term was separately tested.

p-value from omnibus tests for multinomial variables.

Sensitivity analysis

Among the analytic sample, 49.0% students completed the survey remotely outside of their class time, and there was a significant bivariate association between survey type and willingness to use (21.1% willing for in-class survey vs. 23.7% for Online survey; p = .02). To address the possibility that survey type impacted our findings, we conducted a sensitivity analysis of primary multivariable regression models, additionally adjusting for survey type covariate (see Table A1 in the Online Supplemental Material). No meaningful differences between primary and sensitivity analyses were detected.

Discussion

This study provides new information about adolescents’ interest in using novel ONPs. The main findings indicate that nicotine and tobacco naïve adolescents are more willing to use nontherapeutic nicotine gums, lozenges, pouches, and gummies compared to traditional smokeless tobacco and show a slight preference for mint versus fruit flavored oral products. Additionally, the study found substantial sociodemographic disparities in willingness to use these new ONPs, with adolescents who were younger, female, or LGBTQ+ (i.e., lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and other nonheterosexual and or non-cisgender identities) being more willing to use ONPs.

There are several reasons why adolescents might be more willing to use new ONPs than traditional oral smokeless tobacco. Novel ONPs do not mention the term tobacco on their packaging, which eliminates a deterrent that is present in traditional oral smokeless tobacco products. Public health campaigns have successfully increased adolescents’ knowledge of harms of tobacco; therefore, tobacco-containing products may be perceived as having adverse health effects that do not correspond to new ONPs [26,27]. Given the proliferation of nicotine products advertised as “tobacco-free,” public health campaigns should now teach adolescents that nicotine is harmful to them regardless of whether it is synthetic or tobacco-derived. Novel ONPs also require no spitting (unlike smokeless tobacco) and have the appearance of candy, gum, or mints. Thus, these products can be used discreetly and hidden from parents, teachers, and other authority figures. In addition, novel oral products have a modern and sleek design that is uncommon to traditional oral tobacco products and may be enticing to adolescents [28]. This is concerning because the sleek, discreet design of JUUL and other pod-based or disposable nicotine vaping products appeals to adolescents [29] and likely contributed to the adolescent vaping epidemic [30]. Further, emerging products appear to be an important addition to tobacco company portfolios, particularly for established companies [31-34]. For example, Altria, the parent company of Philip Morris USA, owns Skoal (smokeless tobacco), Marlboro (cigarettes), Black & Mild (little cigars), and a minority stake in JUUL(35%) [34,35]. Therefore, continued efforts to denormalize all forms of nicotine/tobacco use, including through adolescent-led public health campaigns, are needed.

Results are consistent with the extant literature that has overwhelmingly found that both fruit- and mint-flavored tobacco products appeal to adolescents [36-38]. Adolescents in this study had slightly greater odds of willingness to use mint-flavored than fruit-flavored products. Mint and fruit are the most widely used tobacco product flavors among adolescents [36-38]. Results are consistent with the 2021 NYTS, which found that mint was the most commonly used flavor of smokeless tobacco and nicotine pouches among US high school students [5]. Similarly, a nationally representative sample of adolescents in 2019 demonstrated that preference for mint-flavored JUUL pods was more prevalent than preference for fruit-flavored JUUL pods among 10th and twelfth graders, especially among frequent users [38]. Mint-flavored gum is more commonly used than fruit-flavored gum [39] and therefore may be more familiar and appealing. In this study, the difference in willingness to use mint-versus fruit-flavored products was small; however, prevalence of adolescents’ use of mint-flavored ONPs warrants ongoing monitoring. FDA has proposed rules prohibiting menthol, which tastes similar to mint, in cigarettes and cigars [40]. If mint-flavored ONPs have long-term appeal to adolescents, prohibiting mint flavors may protect public health. Appeal of mint-flavored ONPs to adolescents should be balanced with their appeal to adults who smoke and seek a potentially less harmful nicotine/tobacco product.

Differences in willingness to use ONPs by sexual and gender identity are mostly consistent with previously identified tobacco use disparities. In this study, LGBTQ + adolescents were more likely to be willing to use ONPs. Nationally representative research conducted in 2013–2016 [41] and 2020 [42] similarly found greater prevalence of past-month tobacco use among LGB + compared to heterosexual adolescents. Moreover, a representative study of middle and high school students in California found that transgender adolescents had greater odds of cigarette smoking than cisgender adolescents [43]. Our study suggests that LGBTQ + adolescents may be at elevated risk for using novel ONPs as well, and potentially progressing to regular ONP use. Ongoing surveillance of ONP use is needed in this high-risk population. In unadjusted analysis, our study also found greater willingness to use ONPs among Hispanic adolescents than adolescents of another race or ethnicity. Non-Hispanic White and Hispanic adolescents generally have higher tobacco use prevalence than Black adolescents [42,44] and adolescents of another race/ethnicity [42]. However, use of snus, which is comparable to ONPs in use experience [45], is highest among non-Hispanic White adolescents [44]. Smokeless tobacco use prevalence is higher among non-Hispanic White high school students than Hispanic or Black students [5]. Further, the findings from this study are different from nationally representative data from the NYTS [46], which show that smokeless tobacco use is traditionally concentrated in cisgender white youth, particularly among males from nonurban regions [46]. The current study found that willingness to use new ONPs was more prevalent among transgender/nonbinary youth, which is consistent with regional data examining traditional smokeless tobacco also from California [47]. Other studies of regions with similar or greater diversity have found interest and use of traditional smokeless tobacco among Hispanic young adults but even higher prevalence among young adults of Asian ancestry (relative to Hispanic) [48,49]. Our results suggest that novel ONPs could draw Hispanic adolescents into tobacco product use.

Finally, in this study, we also found that a greater proportion of financially struggling adolescents were willing to use ONPs, relative to adolescents who were well-off or average. This finding, significant only in unadjusted analysis, is consistent with previous reports of greater cigarette smoking prevalence among lower-income than among higher-income adolescents [44]. Tobacco use disparities persist into adulthood, with disproportionately high tobacco use prevalence among LGBTQ+ and lower-income adults [50]. Tobacco use initiation with ONPs during adolescence has the potential to contribute to ongoing tobacco use disparities. Prior research has shown that willingness to use tobacco products is predictive of future initiation of tobacco [51-54], and thus it is possible that ONPs may potentially contribute to ongoing tobacco use disparities among adolescents. Regulatory action authorizing marketing and sales of novel ONPs should account for the risks they may carry for priority populations.

This study has limitations. Findings may not be representative of regions outside California or of other age groups. However, the diversity of this sample is a notable strength, as adolescent perceptions of smokeless tobacco and novel ONPs in racially/ethnically diverse populations are understudied. All measures were assessed via self-report; thus, there is the possibility of recall bias. These data are cross-sectional and thus we were not able to assess whether willingness to use these products leads to actual product use, although previous research has shown associations with other tobacco products among adolescents who have never used tobacco products [55]. Longitudinal research measuring prospective associations of willingness to use ONPs with subsequent product use would be informative. Additionally, only a single picture of each oral nicotine product packaging was displayed with subsequent willingness to use assessment to reduce participant burden. Thus, future studies are needed to more rigorously assess knowledge, access, and perceptions of these new emerging products in more granular detail. Finally, these data were examined only among nonusers of any tobacco or nicotine product. Limiting the sample to nonusers enabled examination of whether novel ONPs may appeal to nonusers and therefore encourage more adolescents to initiate nicotine/tobacco use. Future studies should examine these associations and how perceptions of and willingness to use ONPs may differ by current or ever tobacco product use.

Implications and conclusions

Novel ONPs (i.e., nontherapeutic nicotine gum, mints, gummies, and pouches) with nontobacco flavors like mint are potential tobacco regulatory targets that might reduce adolescents’ interest in or willingness to use ONPs. Sales of tobacco/nicotine products marketed as “tobacco-free” have substantially increased in the United States since 2016 [1] and monitoring of these new ONPs, particularly as related to adolescent use, is warranted. “Tobacco-free” labels have been found to increase young adults’ intention to use disposable e-cigarettes [56], and may have a similar effect on adolescents’ intention to use ONPs. Adolescents’ preference for mint flavors in novel ONPs is consistent with prior research on e-cigarettes [38] and may warrant regulatory action. Given the recent emergence of these ONPs, further data are needed to understand whether marketing these novel tobacco products as “tobacco-free” is associated with increased use intention, as it may be difficult for adolescents and other consumers to distinguish these new products from therapeutic ONPs that have been authorized by the FDA. Marketing campaigns (e.g., “tobacco-free” moniker) might increase interest from adolescents who are younger and LGBTQ+, as participants from these subgroups were more willing to use ONPs in the current study. Adolescents can develop nicotine dependence symptoms rapidly [57], and experimenting with ONPs may lead to continued use and potential progression to inhalable nicotine/tobacco products (e.g., cigarettes, e-cigarettes). To guide regulatory action, additional research is needed to better understand how these new ONPs are perceived, used, and associated with other tobacco/nicotine use among adolescents.

Supplementary Material

IMPLICATIONS AND CONTRIBUTION.

Sales of new oral nicotine products (ONPs) (i.e., nicotine pouches, gum, lozenges, and gummies) are increasing in the United States. Adolescents were more willing to use ONPs in mint (vs. fruit) flavor. Younger and LGBTQ + adolescents may be at greater risk of using these products.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute and the FDA Center for Tobacco Products (CTP) under Award Number U54CA180905, National Cancer Institute under award number R01CA229617, National Institute on Drug Abuse under award number K24DA048160, and the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (K01HL148907).

Footnotes

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2022.09.027.

Disclaimer: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or the FDA.

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- [1].Marynak KL, Wang X, Borowiecki M, et al. Nicotine pouch unit sales in the US, 2016-2020. JAMA 2021;326:566–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].East KA, Reid JL, Rynard VL, Hammond D. Trends and Patterns of tobacco and nicotine product Use among youth in Canada, England, and the United States from 2017 to 2019. J Adolesc Health 2021;69:447–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Li L, Borland R, Cummings KM, et al. Patterns of non-cigarette tobacco and nicotine use among current cigarette smokers and recent quitters: Findings from the 2020 ITC four country smoking and vaping survey. Nicotine Tob Res 2021;23:1611–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Meza R, Jimenez-Mendoza E, Levy DT. Trends in tobacco use among adolescents by grade, sex, and race, 1991-2019. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e2027465. e2027465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Gentzke AS, Wang TW, Cornelius M, et al. Tobacco product use and associated factors among middle and high school students – national youth tobacco survey, United States, 2021. MMWR Surveill Summ 2022;71:1–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Zhu S-H, Braden K, Zhuang Y-L, et al. Results of the statewide 2019-2020 California student tobacco survey. San Diego, CA: University of California San Diego; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Federal Trade Commission. Smokeless tobacco report for 2020. 2021. Available at: https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/reports/federal-trade-commission-cigarette-report-2020-smokeless-tobacco-report-2020/p114508fy20smokelesstobaccop114508fy20smokelesstobacco.pdf. Accessed November 15, 2022.

- [8].Food and Drug Adminstration (FDA). FDA permits marketing of new oral tobacco products through premarket tobacco product application pathway. 2021. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-permits-marketing-new-oral-tobacco-products-through-premarket-tobacco-product-application. Accessed December 10, 2021.

- [9].Food and Drug Adminstration (FDA). FDA Warns manufacturer for marketing Illegal flavored nicotine gummies. 2022. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-warns-manufacturer-marketing-illegal-flavored-nicotine-gummies?utm_campaign=ctp-ntn&utm_content=pressrelease&utm_medium=email&utm_source=govdelivery&utm_term=stratcomms. Accessed August 18, 2022.

- [10].Yolton K, Dietrich K, Auinger P, et al. Exposure to environmental tobacco smoke and cognitive abilities among US children and adolescents. Environ Health Perspect 2005;113:98–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Dwyer JB, McQuown SC, Leslie FM. The dynamic effects of nicotine on the developing brain. Pharmacol Therap 2009;122:125–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Chen R, Clifford A, Lang L, Anstey KJ. Is exposure to secondhand smoke associated with cognitive parameters of children and adolescents?-a systematic literature review. Ann Epidemiol 2013;23:652–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Gould TJ, Leach PT. Cellular, molecular, and genetic substrates underlying the impact of nicotine on learning. Neurobiol Learn Mem 2014;107:108–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Lucy Goods Inc. PMTA accepted for scientific review and key data accepted for publication by the society for research on nicotine and tobacco (SRNT). 2021. Available at: https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/lucy-goods-inc-pmta-accepted-for-scientific-review-and-key-data-accepted-for-publication-by-the-society-for-research-on-nicotine-and-tobacco-srnt-301238837.html. Accessed December 8, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- [15].R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company. Reynolds submits first VELO dissolvable nicotine lozenge premarket tobacco product applications. 2020. Available at: https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/reynolds-submits-first-velo-dissolvable-nicotine-lozenge-premarket-tobacco-product-applications-301116768.html. Accessed November 28, 2022.

- [16].Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids. States & localities that have restricted the sale offlavored tobacco products. 2022. Available at: https://www.tobaccofreekids.org/assets/factsheets/0398.pdf. Accessed November 15, 2022.

- [17].Harlow AF, Vogel E, Tackett AP, et al. Adolescent use of flavored tobacco-free oral nicotine products. Pediatrics 2022;150:e2022056586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Food and Drug Adminstration (FDA). Guidance Document: Tobacco products: Principles for designing and conducting tobacco product perception and intention studies. Docket Number: FDA-2019-D-4188 2022. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/tobacco-products-principles-designing-and-conducting-tobacco-product-perception-and-intention. Accessed August 25, 2022.

- [19].Kwon E, Seo D-C, Lin H-C, Chen Z. Predictors of youth e-cigarette use susceptibility in a US nationally representative sample. Addict Behav 2018;82:79–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Sawdey MD, Day HR, Coleman B, et al. Associations of risk factors of e-cigarette and cigarette use and susceptibility to use among baseline PATH study youth participants (2013–2014). Addict Behav 2019;91:51–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Ambrose BK, Rostron BL, Johnson SE, et al. Perceptions of the relative harm of cigarettes and e-cigarettes among US youth. Am J Prev Med 2014;47:S53–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Muthén L. Mplus user’s guide. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén; 1998;2017. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Vittinghoff E, Glidden DV, Shiboski SC, McCulloch CE. Logistic regression. In: Regression Methods in Biostatistics. Boston, MA: Springer; 2012:139–202. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Ser B (Methodological) 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Shrestha N. Detecting multicollinearity in regression analysis. Am J Appl Mathematics Stat 2020;8:39–42. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Strong DR, Messer K, White M, et al. Youth perception of harm and addictiveness of tobacco products: Findings from the population assessment of tobacco and health study (wave 1). Addict Behav 2019;92:128–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Agaku IT, Perks SN, Odani S, Glover-Kudon R. Associations between public e-cigarette use and tobacco-related social norms among youth. Tob Control 2020;29:332–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].World Health Organization (WHO). WHO study group on tobacco product regulation. Report on the scientific basis of tobacco product regulation: Eighth report of a WHO study group. 2021. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240022720. Accessed December 8, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Kavuluru R, Han S, Hahn EJ. On the popularity of the USB flash drive-shaped electronic cigarette JUUL. Tob Control 2019;28:110–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Cullen KA, Ambrose BK, Gentzke AS, et al. Notes from the Field: use of electronic cigarettes and any tobacco product among middle and high school students – United States, 2011–2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67:1276–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].McNeill A, Sweanor D. Beneficence or maleficence–big tobacco and smokeless products. Addiction 2009;104:167–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Dutra LM, Grana R, Glantz SA. Philip Morris research on precursors to the modern e-cigarette since 1990. Tob Control 2017;26:e97–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Truth Initiative. Spinning a new tobacco industry. 2019. Available at: https://truthinitiative.org/sites/default/files/media/files/2019/11/Tobacco%20Industry%20Interference%20Report_final111919.pdf. Accessed August 9, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Brink S, Nahhas G, Cummings KM, et al. Cigarette brand preferences of adolescent and adult smokers in the United States. Tob Induced Dis 2018;16. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Delnevo CD, Hrywna M, Miller Lo EJ, Wackowski OA. Examining market trends in smokeless tobacco sales in the United States: 2011–2019. Nicotine Tob Res 2021;23:1420–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Rose SW, Johnson AL, Glasser AM, et al. Flavour types used by youth and adult tobacco users in wave 2 of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study 2014-2015. Tob Control 2020;29:432–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Cullen KA, Gentzke AS, Sawdey MD, et al. E-Cigarette use among youth in the United States, 2019. JAMA 2019;322:2095–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Leventhal AM, Miech R, Barrington-Trimis J, et al. Flavors of e-cigarettes used by youths in the United States. JAMA 2019;322:2132–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Martyn DM, Lau A. Chewing gum consumption in the United States among children, adolescents and adults. Food Addit Contam Part A Chem Anal Control Expo Risk Assess 2019;36:350–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Food and Drug Adminstration. FDA proposes rules prohibiting menthol cigarettes and flavored cigars to prevent initiation, significantly reduce tobacco-related disease and death [press release]. 2022. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-proposes-rules-prohibiting-menthol-cigarettes-and-flavored-cigars-prevent-youth-initiation. Accessed May 10, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Kasza KA, Edwards KC, Tang Z, et al. Correlates of tobacco product initiation among youth and adults in the USA: Findings from the PATH study Waves 1-3 (2013-2016). Tob Control 2020;29:s191–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Gentzke AS, Wang TW, Jamal A, et al. Tobacco product use among middle and high school students – United States, 2020. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:1881–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Day JK, Fish JN, Perez-Brumer A, et al. Transgender youth substance use disparities: Results from a population-based sample. J Adolesc Health 2017;61:729–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Miech RA, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, et al. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975-2020: Volume I, Secondary school students. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- [45].Plurphanswat N, Hughes JR, Fagerström K, Rodu B. Initial information on a novel nicotine product. Am J Addict 2020;29:279–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Odani S, Armour BS, Agaku IT. Racial/ethnic disparities in tobacco product use among middle and high school students—United States, 2014–2017. Morbidity Mortality Weekly Rep 2018;67:952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Zhu S-H, Lee J, Zhuang Y-L, et al. Tobacco use among high school students in Santa Clara county: Findings from the 2017–18 California student tobacco survey. San Diego, CA: Center for Research and Intervention in Tobacco Control (CRITC), University of California, San Diego. Available at: https://publichealth.sccgov.org/sites/g/files/exjcpb916/files/castudent-survey-2019.pdf. Accessed November 28, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- [48].Clendennen SL, Mantey DS, Wilkinson AV, et al. Digital marketing of smokeless tobacco: A longitudinal analysis of exposure and initiation among young adults. Addict Behav 2021;117:106850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Mantey DS, Clendennen SL, Pasch KE, et al. Marketing exposure and smokeless tobacco use initiation among young adults: A longitudinal analysis. Addict Behav 2019;99:106014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Drope J, Liber AC, Cahn Z, et al. Who’s still smoking? Disparities in adult cigarette smoking prevalence in the United States. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:106–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Cole AG, Kennedy RD, Chaurasia A, Leatherdale ST. Exploring the predictive validity of the susceptibility to smoking construct for tobacco cigarettes, alternative tobacco products, and E-cigarettes. Nicotine Tob Res 2019;21:323–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Lienemann BA, Rose SW, Unger JB, et al. Tobacco advertisement liking, vulnerability factors, and tobacco use among young adults. Nicotine Tob Res 2019;21:300–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Fulmer EB, Neilands TB, Dube SR, et al. Protobacco media exposure and youth susceptibility to smoking cigarettes, cigarette experimentation, and current tobacco use among US youth. PLoS One 2015;10:e0134734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Silveira ML, Conway KP, Everard CD, et al. Longitudinal associations between susceptibility to tobacco use and the onset of other substances among US youth. Prev Med 2020;135:106074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Barrington-Trimis JL, Liu F, Unger JB, et al. Evaluating the predictive value of measures of susceptibility to tobacco and alternative tobacco products. Addict Behav 2019;96:50–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Chen-Sankey J, Ganz O, Seidenberg A, Choi K. Effect of a ‘tobacco-free nicotine’ claim on intentions and perceptions of Puff Bar e-cigarette use among non-tobacco-using young adults. Tob Control 2021. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2021-056957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].DiFranza JR, Rigotti NA, McNeill AD, et al. Initial symptoms of nicotine dependence in adolescents. Tob Control 2000;9:313e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.