Abstract

BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES:

Flavored non-tobacco oral nicotine products (eg, nicotine pouches and nontherapeutic nicotine gum, lozenges, tablets, gummies), are increasingly marketed in the United States. Prevalence of non-tobacco oral nicotine product use among adolescents is unknown.

METHODS:

We calculated prevalence of ever and past 6-month use of nicotine pouches, other non-tobacco oral nicotine products (ie, gum, lozenges, tablets, and/or gummies), e-cigarettes, cigarettes, hookah or waterpipe, cigars, cigarillos, and snus among high school students in Southern California between September and December 2021. Generalized linear mixed models tested associations of sociodemographic factors and tobacco-product use with use of any non-tobacco oral nicotine product.

RESULTS:

Among the sample (n = 3516), prevalence was highest for e-cigarettes (ever: 9.6%, past 6-month: 5.5%), followed by non-tobacco oral nicotine products (ever: 3.4%, past 6-month: 1.7%), and <1% for other products. Ever users of combustible tobacco (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 77.6; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 39.7–152) and ever users of noncombustible tobacco (aOR = 40.4; 95% CI= 24.3–67.0) had higher odds of ever using non-tobacco oral nicotine products, compared to never users of combustible and noncombustible tobacco. Use of any non-tobacco oral nicotine product was greater for Hispanic (versus all other races/ethnicities except Asian, aOR = 2.58; 95% CI = 1.36–4.87), sexual minority (versus heterosexual, aOR=1.63; 95% CI = 1.03–2.57), gender minority (versus male, aOR = 2.83; 95% CI = 1.29–6.19), and female (versus male, aOR=1.92, 95% CI = 1.20–3.06) participants.

CONCLUSIONS:

Non-tobacco oral nicotine products were the second most prevalent nicotine product used by adolescents. They were disproportionately used by certain racial or ethnic, sexual, or gender minority groups, and those with a history of nicotine use. Adolescent nontobacco oral nicotine product use surveillance should be a public health priority.

Non-tobacco oral nicotine products are a relatively new type of commercial nicotine product that include flavored nicotine pouches, nontherapeutic nicotine gums, lozenges, and tablets, and nicotine gummies (Fig 1).1,2 Although therapeutic nicotine gums and lozenges (ie, nicotine replacement therapy for cigarette smoking cessation) have been on the market for decades, a new sector of commercial oral nicotine products that are advertised as tobacco-free and not approved as cessation aids (ie, nontherapeutic) have recently entered the market. United States sales of non-tobacco nicotine pouches have increased substantially in recent years (commercial market share: 0.9% in 2018, to 4.0% in 2019 in the United States oral nicotine or tobacco commercial market).3 New nontobacco oral nicotine products may be of interest to adolescents because of the ability to conceal use from authority figures, similarity to preferred food products (eg, gum), and availability in appealing flavors. New non-tobacco oral nicotine products also employ marketing approaches that may attract youth, including availability in fruit and dessert flavors, digital marketing campaigns, and marketing themes connoting minimal harm.1,2

FIGURE 1.

Examples of flavored non-tobacco oral nicotine products on the market. A, Nicotine pouches. B, Nontherapeutic nicotine gum. C, Nontherapeutic nicotine lozenges. D, Nicotine gummies.

National surveys such as the National Survey on Drug Use and Health,4 Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System,5 and Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health6 do not currently include measures of nontobacco oral nicotine product use. Consequently, little is known about how common non-tobacco oral nicotine product use is among United States adolescents and whether there are certain groups that are at greater risk for use. In one study, ever use of non-tobacco nicotine pouches (which are similar to snus but do not contain tobacco plant) among Dutch adolescents (13 to 17 years old) surveyed in 2020 was <1%.7 However, no published studies have examined the prevalence of nicotine pouch use among United States adolescent populations or the prevalence of other novel non-tobacco oral nicotine products (eg, gums, lozenges, and gummies), which resemble candy and can be easily concealed. Because nicotine exposure in adolescence may adversely affect adolescent brain development and increase risk of nicotine addiction and attention, memory, learning, and impulse control problems,8–10 national surveillance of adolescent use of these products may be warranted if adolescent use of nontobacco oral nicotine products is of appreciable prevalence or elevated among vulnerable subgroups.

In the current study, we examine the prevalence of ever and past 6-month use of non-tobacco oral nicotine products, including nicotine pouches and flavored nontherapeutic nicotine gums, lozenges, tablets, and gummies, among Southern California ninth and tenth graders during Fall 2021. We present prevalence estimates relative to other tobacco product use (e-cigarettes, combustible cigarettes, hookah, snus, large cigars, and cigarillos). We also examine whether sociodemographic factors and other tobacco product use are correlated with use of non-tobacco oral nicotine products.

METHODS

Data are from an ongoing survey study of behavioral health among Southern California adolescents. Students were recruited in ninth grade from a total of 11 schools in 7 school districts from Los Angeles, Riverside, San Bernardino, Orange, or Imperial counties. Recruitment of ninth grade adolescents was conducted in 2 waves. In the first recruitment wave during the 2020 to 2021 academic year, ninth graders enrolled at participating schools were eligible. The second recruitment wave involved a new population of ninth graders enrolled in a subset of 4 participating schools that took place during Fall 2021 of the 2021 to 2022 academic year. Data for the current study are from the Fall 2021 data collection (September 30 to December 14, 2021), when students from the first recruitment wave were in tenth grade and those from the second recruitment wave were in ninth grade. Between September and December 2021, 8512 students were eligible, 4203 enrolled in the study (parental consent and student assent obtained), and 3764 students (ninth grade, n = 1236; tenth grade, n = 2528) took the Fall 2021 survey (Supplemental Fig 3). The analytic sample was restricted to 3516 participants with nonmissing data on nicotine and tobacco product use. Most students completed in-classroom surveys collected on site at their respective schools. Students absent during data collection days were sent a link to the survey and invited to complete the survey remotely outside of their class time.

Ethics Statement

The study was approved by the University of Southern California Institutional Review Board. Written parental consent and student assent were obtained before data collection.

Measures

Non-Tobacco Oral Nicotine Product Use

Survey items assessed ever (versus never) and past 6-month (versus no past 6-month) use of (A) nicotine pouches and (B) other non-tobacco oral nicotine products (ie, gum, lozenges, tablets, and/or gummies). Nicotine pouches and other nontobacco oral nicotine products were examined separately and subsequently collapsed for primary analyses (ie, representing any nontobacco oral nicotine product based on use of either nicotine pouches or other oral products).

Other Tobacco Product Use

Additional survey items assessed ever and past 6-month use of combustible cigarettes, e-cigarettes, snus, cigars, little cigars or cigarillos, and hookah or waterpipe. Despite its similarity to nicotine pouches, snus was not considered a non-tobacco oral nicotine product in this study as it contains tobacco plant. The survey did not include questions on use of traditional smokeless tobacco products (eg, dip or chewing tobacco), which is rare among adolescents in similar Southern California cohorts.11 We created variables for any combustible tobacco (ie, cigarettes, cigars, little cigars or cigarillos, hookah or waterpipe), any noncombustible tobacco product (ie, e-cigarettes, snus), and a mutually exclusive 4-category variable distinguishing between dual and exclusive ever use of combustible and noncombustible tobacco products (dual ever use of combustible and noncombustible tobacco, exclusive ever use of combustible tobacco, exclusive ever use of noncombustible tobacco, and never use of either combustible or noncombustible tobacco).

Sociodemographic Characteristics

Adolescents self-reported race and ethnicity (Hispanic, Non-Hispanic Asian, Non-Hispanic all other races [American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, White, multiracial, another race were assessed separately and collapsed in analysis]), sexual identity (heterosexual, sexual minority identity [asexual, bisexual, gay, lesbian, pansexual, queer, questioning], prefer not to disclose), gender identity (male or masculine, female or feminine, transgender or nonbinary [transgender male, transgender female, gender variant or nonbinary, another gender], prefer not to disclose), and highest parental or caregiver education (less than high school [eighth grade or less, less than high school], high school graduate, some college or college graduate [some college, college graduate], advanced degree, don’t know), and perceived socioeconomic status (financially struggling or in poverty, all other socioeconomic categories [it varied, about average, pretty well off financially]).

Statistical Analysis

We calculated the prevalence of ever (yes or no) and past 6-month (yes or no) use of nicotine pouches, other non-tobacco oral nicotine products (ie, gum, lozenges, tablets, and/or gummies), and each tobacco product (ie, combustible cigarettes, e-cigarettes, snus, cigars, little cigars or cigarillos, hookah/waterpipe) among the full sample. We examined the prevalence of ever and past 6-month use of any non-tobacco oral nicotine product (ie, nicotine pouches or other non-tobacco oral nicotine product) by sociodemographic characteristics and by combustible and noncombustible tobacco use history. To examine correlates of oral nicotine product use, we fit separate unadjusted generalized linear mixed models that accounted for clustering within schools to produce odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the association of each sociodemographic factor and combustible and noncombustible tobacco use history (independent variables) with ever and past 6-month use of any non-tobacco oral nicotine product (dependent variables). We additionally fit multivariable generalized linear mixed models adjusting for all sociodemographic factors. Missing data on sociodemographic factors ranged from 0.03% (grade) to 3.0% (parental education). Missing values were assigned a missing indicator and included in the analysis. Analyses used SAS v.9.4.

RESULTS

Among the sample of 3516 adolescents with nonmissing data on tobacco or nicotine use, 31.9% were in ninth grade and 68.1% were in tenth grade (Table 1). Most identified as Hispanic (47.3%) or Asian (32.0%), and 17.9% identified as another race and ethnicity (7.9% multiple races, 6.9% White, 1.3% Black, 0.31% Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, 0.06% American Indian, and 1.4% all other races). A majority reported that the highest level of parental education was some college or greater, and only 5.9% of participants reported that their family struggled financially or were in poverty. Approximately one-quarter (23.0%) of participants identified as sexual minority identity, and 4.1% preferred not to report their sexual identity. For gender identity, 46.6% of participants identified as female or feminine, 43.3% as male or masculine, 5.2% as transgender, gender nonbinary, or another gender, and 3.6% preferred not to say.

TABLE 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of 3516 Adolescents in Southern California Between September and December 2021

| Sociodemographic Characteristic | No. (%) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| High school grade | |

| Ninth grade | 1121 (31.9) |

| Tenth grade | 2395 (68.1) |

| Race and ethnicity | |

| Hispanic | 1663 (47.3) |

| Asian | 1125 (32.0) |

| Multiple races | 277 (7.9) |

| White | 242 (6.9) |

| Black | 47 (1.3) |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 11 (0.31) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 2 (0.06) |

| Another race | 48 (1.4) |

| Missing | 101 (2.9) |

| Highest parental education | |

| 8th grade or less | 81 (2.3) |

| Some high school | 176 (5.0) |

| High school | 449 (12.8) |

| Some college | 459 (13.1) |

| College degree | 1087 (30.9) |

| Advanced degree | 766 (21.8) |

| Don’t know | 394 (11.2) |

| Missing | 104 (3.0) |

| Perceived socioeconomic status | |

| Well-off | 984 (28.0) |

| About average | 1845 (52.5) |

| Struggling financially or in poverty | 206 (5.9) |

| It varied | 415 (11.8) |

| Missing | 66 (1.9) |

| Sexual identity | |

| Heterosexual | 2507 (71.3) |

| Bisexual | 328 (9.3) |

| Questioning | 163 (4.6) |

| Pansexual | 107 (3.0) |

| Lesbian | 56 (1.6) |

| Gay | 41 (1.2) |

| Asexual | 40 (1.1) |

| Queer | 33 (0.94) |

| Another identity | 42 (1.2) |

| Prefer not to disclose | 145 (4.1) |

| Missing | 54 (1.5) |

| Gender identity | |

| Female or feminine | 1638 (46.6) |

| Male or masculine | 1524 (43.3) |

| Gender variant or nonbinary | 101 (2.9) |

| Transgender male | 18 (0.51) |

| Transgender female | 6 (0.17) |

| Another gender identity | 57 (1.6) |

| Prefer not to disclose | 128 (3.6) |

| Missing | 44 (1.3) |

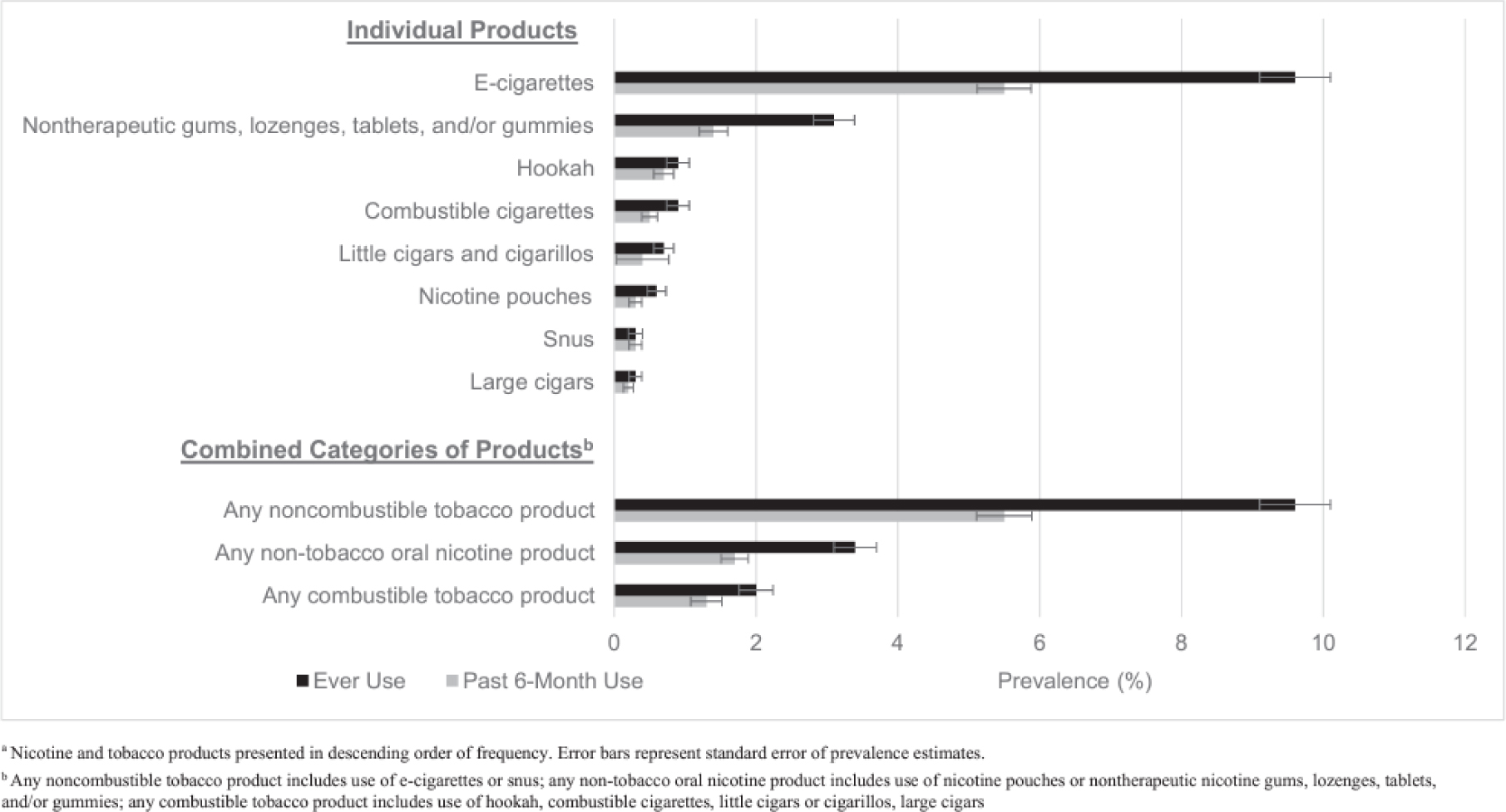

The most prevalent nicotine or tobacco product used was e-cigarettes (9.6% ever, 5.5% past 6 month use), followed by nicotine gums, lozenges, tablets, and/or gummies (3.1% ever, 1.4% past 6 month use; Fig 2). For all other products, ever and past 6 month use prevalence was <1%, including nontobacco nicotine pouches (0.6% ever, 0.3% past 6 month use). Overall, 3.4% of participants reported ever use and 1.7% reported past 6-month use of any non-tobacco oral nicotine product, whereas 9.6% reported ever use and 5.5% reported past 6-month use of any noncombustible tobacco product (ie, e-cigarettes, snus) and 2.0% of participants reported ever use and 1.3% reported past 6-month use of any combustible tobacco product (ie, cigarettes, cigars, little cigars or cigarillos, hookah).

FIGURE 2.

Prevalence of ever and past 6-month use of 8 different nicotine and tobacco products among 3516 adolescents in Southern California between September and December 2021.a

In adjusted analyses, the odds of ever use of any non-tobacco oral nicotine product were elevated for tenth graders (versus ninth graders, adjusted OR [aOR]: 2.08, 95% CI: 1.23–3.50), Hispanic participants (versus all other race and ethnicities except Asian, aOR: 2.58, 95% CI: 1.36–4.87), participants reporting a sexual minority identity (versus heterosexual, aOR: 1.63, 95% CI: 1.03–2.57), participants identifying as female or feminine (versus male or masculine, aOR: 1.92, 95% CI: 1.20–3.06), and transgender or nonbinary youth (versus male or masculine, aOR: 2.83, 95% CI: 1.29–6.19) (Table 2). Sociodemographic correlates were similar for past 6-month use of any non-tobacco oral nicotine product (Supplemental Table 4).

TABLE 2.

Sociodemographic Correlates of Ever Use of Any Non-Tobacco Oral Nicotine Product Among 3516 Adolescents in Southern California Between September and December 2021

| Sociodemographic Factor | No. (%) Oral Nicotine Product Usea | Unadjusted Prevalence Difference (95% CI) | Unadjusted OR (95% CI)b | Adjusted OR (95% CI)b,c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| High school grade | ||||

| Ninth grade | 22 (2.0) | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Tenth grade | 96 (4.0) | 2.0 (0.9 to 3.2) | 2.02 (1.24 to 3.32) | 2.08 (1.23 to 3.50) |

| Race and ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic | 79 (4.7) | 2.4 (0.9 to 3.9) | 2.15 (1.25 to 3.70) | 2.58 (1.36 to 4.87) |

| Asian | 22 (2.0) | −0.3 (−1.0 to 1.7) | 0.99 (0.50 to 1.98) | 1.52 (0.71 to 3.25) |

| All other racesd | 17 (2.3) | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Parental education | ||||

| Less than high school | 15 (5.8) | 2.9 (−0.06 to 5.9) | 2.06 (1.12 to 3.80) | 1.64 (0.87 to 3.09) |

| High school | 19 (4.2) | 1.3 (−0.07 to 3.4) | 1.41 (0.81 to 2.45) | 1.23 (0.70 to 2.17) |

| Some college or college degree | 45 (2.9) | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Advanced degree | 20 (2.6) | −0.3 (−1.7 to 1.1) | 0.93 (0.54 to 1.59) | 1.09 (0.63 to 1.89) |

| Don’t know | 11 (2.8) | −0.1 (−2.0 to 1.7) | 1.00 (0.51 to 1.95) | 1.02 (0.51 to 2.04) |

| Subjective financial status | ||||

| Struggling or in poverty | 14 (6.8) | 3.7 (1.2 to 6.3) | 2.27 (1.27 to 4.08) | 1.76 (0.96 to 3.23) |

| Well-off, average, or varied | 99 (3.1) | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Sexual identity | ||||

| Heterosexual | 66 (2.6) | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Sexual minoritye | 44 (5.4) | 2.8 (1.1 to 4.5) | 2.13 (1.44 to 3.16) | 1.63 (1.03 to 2.57) |

| Prefer not to disclose | 5 (3.4) | 0.8 (−2.2 to 3.9) | 1.48 (0.58 to 3.76) | 1.29 (0.49 to 3.44) |

| Gender identity | ||||

| Male or masculine | 28 (1.8) | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Female or feminine | 67 (4.1) | 2.3 (1.1 to 3.4) | 2.29 (1.46 to 3.58) | 1.92 (1.20 to 3.06) |

| Transgender or nonbinaryf | 13 (7.1) | 5.3 (1.5 to 9.1) | 4.10 (2.08 to 8.10) | 2.83 (1.29 to 6.19) |

| Prefer not to disclose | 5 (3.9) | 2.1 (−1.4 to 5.5) | 2.31 (0.87 to 6.11) | 1.69 (0.60 to 4.76) |

Ref., reference; No., number.

Use of nicotine pouches or nontherapeutic nicotine gums, lozenges, tablets, and/or gummies.

Estimate of association with ever versus never oral nicotine use from generalized linear mixed models accounting for clustering with schools.

Adjusted model includes all sociodemographic factors as simultaneous regressors.

All other races includes American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, White, multiracial, another race.

Sexual minority identity includes asexual, bisexual, gay, lesbian, pansexual, queer, and questioning.

Transgender or nonbinary includes transgender male, transgender female, gender variant or nonbinary, another gender.

The prevalence of ever use of any non-tobacco oral nicotine product was greatest among dual ever users of combustible and noncombustible tobacco products (43.6%; prevalence difference [PD] versus never use: 42.8%, 95% CI: 29.7%–55.9%), followed by exclusive ever users of combustible tobacco (26.7%; PD versus never use: 25.8%, 95% CI: 3.4%–48.2%), and exclusive ever users of noncombustible tobacco products (22.2%; PD versus never use: 21.3%, 95% CI: 16.5%–26.2%) (Table 3). Among never users of either combustible or noncombustible tobacco, 0.85% had ever used any non-tobacco oral nicotine product. Compared to never users of combustible and noncombustible tobacco, aORs were 77.6 (95% CI: 39.7–152) for ever users of combustible tobacco, and 40.4 (95% CI: 24.3–67.0) for ever users of noncombustible tobacco products. Similar patterns were seen for past 6-month use of any non-tobacco oral nicotine product (Supplemental Table 4).

TABLE 3.

Tobacco Product Correlates of Ever Use of Any Non-Tobacco Oral Nicotine Product Among 3516 Adolescents in Southern California Between September and December 2021

| Tobacco Product Use Historya | No. Participants | No. (%) Oral Nicotine Product Useb | Unadjusted Prevalence Difference (95% CI) | Unadjusted OR (95% CI)c | Adjusted OR (95% CI)c,d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Dual use combustible and noncombustible tobacco | 55 | 24 (43.6) | 42.8 (29.7 to 55.9) | 89.9 (46.7 to 173) | 90.1 (43.5 to 187) |

| Exclusive combustible tobaccoe | 15 | 4 (26.7) | 25.8 (3.4 to 48.2) | 42.2 (12.6 to 141) | 45.3 (12.8 to 160) |

| Exclusive noncombustible tobacco | 284 | 63 (22.2) | 21.3 (16.5 to 26.2) | 33.1 (20.7 to 53.0) | 33.4 (19.8 to 56.5) |

| Never use | 3162 | 27 (0.85) | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Any combustible tobacco | 70 | 28 (40.0) | 39.2 (27.7 to 50.6) | 77.4 (42.1 to 143) | 77.6 (39.7 to 152) |

| Never use | 3162 | 27 (0.85) | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Any noncombustible tobacco | 339 | 87 (25.7) | 24.8 (20.2 to 29.5) | 40.1 (25.5 to 62.9) | 40.4 (24.3 to 67.0) |

| Never use | 3162 | 27 (0.85) | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

Combustible tobacco includes combustible cigarettes, hookah or waterpipe, little cigars or cigarillos, big cigars. Noncombustible tobacco includes e-cigarettes and snus. Never use includes participants who never used combustible and noncombustible tobacco.

Use of nicotine pouches or nontherapeutic nicotine gums, lozenges, tablets, and/or gummies

Estimate of association with ever versus never oral nicotine use from generalized linear mixed models accounting for clustering with schools.

Adjusted model includes tobacco product use history and all sociodemographic factors from Table 2.

Regression estimates should be interpreted with caution due to events <5 among exclusive combustible tobacco users.

DISCUSSION

This study represents one of the first attempts to estimate the prevalence of flavored non-tobacco oral nicotine product use among adolescents in the United States. Among adolescents in ninth and tenth grades from Southern California, flavored non-tobacco oral nicotine products were the second most commonly used nicotine product, behind e-cigarettes. Hispanic ethnicity, female and gender minority identity, and sexual minority identity were associated with greater odds of use of nontobacco oral nicotine products among adolescents. Non-tobacco oral nicotine product use was greatest among adolescents who had ever used both combustible and other noncombustible tobacco products, and prevalence was rare among never users of tobacco products. This is the first study to estimate the prevalence of a new subclass of nontherapeutic nontobacco oral nicotine products (ie, gum, lozenges, tablets, and gummies), and only the second to estimate the prevalence of non-tobacco nicotine pouch use among adolescents.7 Prevalence estimates in this regional cohort were low across all nicotine or tobacco products, resembling recent national trends12–14; however, rates of nontherapeutic non-tobacco oral nicotine products in this sample, particularly for nicotine gum, lozenges, tablets, and/or gummies, were not negligible and were more common than almost all other nicotine products (with the exception of e-cigarettes).

Nontherapeutic non-tobacco nicotine gums, lozenges, tablets, and gummies have several attributes that might attract youth. For example, Krave, Lucy, Solace, and Rogue brand products are available in flavors such as “Cherry Bomb,” “Blue Raz,” “Fruit Medley,” and “Pomegranate” and resemble candies, which may create a sense of familiarity for youth. The act of putting a piece of gum or gummy in the mouth might feel intuitive and less risky for an adolescent, in contrast to nicotine or tobacco products that are inhaled or are packaged in pouches, both of which may seem foreign to youth with little experience using tobacco products. Importantly, oral nicotine products are discreet and easily concealed; without packaging, and in some cases, even with packaging, many products are indistinguishable from regular gum or candy, making them easy to hide from parents, teachers, or other authority figures. Many nontherapeutic oral nicotine products also have modern packaging designs that distinguish these products from traditional nicotine replacement therapy products (eg, Nicorette), and brands have engaged in digital media campaigns in which their oral nicotine products are marketed as a lower risk alternative to inhalable nicotine products.2 Flavors, concealability, design, and digital marketing were all identified as important drivers behind the rise in youth use of JUUL e-cigarettes between 2015 and 201815 and the subsequent rise in youth use of PuffBar and other disposable e-cigarettes.13 It is plausible that nontherapeutic flavored nicotine gums, lozenges, and gummies may take the place of other nicotine products in the coming years, given their unique features, similarity in marketing to other nicotine products that have gained rapid popularity in this age group, and apparent appeal to young people.

On the other hand, we found that the prevalence of nicotine pouch use, another type of non-tobacco oral nicotine product, was low (<1%) among adolescents in our sample, similar to a previous Dutch study.7 Non-tobacco nicotine pouches are placed in between the lip and gums and resemble Swedish style snus, but instead of shredded tobacco filling, the pouches contain microcrystalline cellulose with nicotine salt, flavors, sweeteners, and other additives.2,16,17 Although there is no previous estimate of nicotine pouch use prevalence in American youth, ever use estimates of snus has been low among previous national samples of United States adolescents13,18 and was low in the current cohort. It is possible that oral nicotine or tobacco products in pouch forms (whether as snus or nicotine pouches) are either less appealing or more difficult to access than other nicotine or tobacco products among adolescents in the United States. However, in contrast to mass-manufactured snus products, which are available only in mint variants, mass-marketed non-tobacco nicotine pouch brands such as Velo (British American Tobacco), On! (Altria), and Zyn (Swedish Match) come in fruity flavors, such as “Citrus Burst.”2 Given these characteristics and evidence of increasing marketing of nicotine pouches in the United States,1,2 national monitoring of non-tobacco nicotine pouch use in American youth is warranted.

Similar to research on other tobacco products,19–21 adolescents from disadvantaged populations appeared to be at greatest risk of having used non-tobacco oral nicotine products, including sexual and gender minority youth. Hispanic adolescents were at greater risk of having used oral nicotine products compared with those with other racial and ethnic identities. E-cigarette use is increasing among Hispanic populations,19 which may at least partially explain the differences by Hispanic ethnicity observed in this study given that oral nicotine use was highly correlated with a history of other noncombustible tobacco use. Additionally, previous studies demonstrate sexual identity disparities in adolescent use of cigarettes20,22–25 and e-cigarettes.26–29 However, very little data exists on gender identity disparities in tobacco product use among adolescents.30–32 Young people are increasingly identifying as gender nonbinary or nonconforming,33 and it is critical to continue to monitor gender identity disparities in oral nicotine product use as well as other tobacco product use that may harm adolescent health.

Female adolescents were more likely than males to have used nontobacco oral nicotine products. Oral nicotine products are easily shareable and discrete, attributes which may appeal to adolescent females who tend to use nicotine for social reasons and are more likely than males to experience societal disapproval and stigma of substance use.34,35 Previous research also indicates that male youth are more likely than females to use tobacco products for the “nicotine rush.”36 Nicotine absorption through mucous membranes that occurs from oral nicotine product use is slower than lung absorption,37 potentially resulting in a less noticeable nicotine “buzz” than smoking or vaping.

As in previous studies in adult populations,1,7,38 we found that most adolescents who had ever used non-tobacco oral nicotine products had also used e-cigarettes or cigarettes, with the greatest prevalence among dual ever users of combustible and noncombustible tobacco products. However, it is not clear from our data whether non-tobacco oral nicotine products were initiated before or after initiation of e-cigarettes and combustible tobacco. Given that use of other noncombustible nicotine products such as e-cigarettes increases risk of subsequent initiation of combustible cigarette smoking39 and cannabis use,40 there is reason to be concerned about whether non-tobacco oral nicotine product use increases risk of using other harmful substances. Notably, <1% of adolescents who had never used other nicotine or tobacco products reported using any nontobacco oral nicotine products. It will be important to continue to monitor non-tobacco oral nicotine use to see whether prevalence among never tobacco users changes in the future.

This research is subject to some limitations. Although non-tobacco oral nicotine products were common in our sample relative to other nicotine products, the overall prevalence of nicotine and tobacco product use in this study was low. It was, therefore, necessary to collapse sociodemographic variables in analyses, which inhibited more granular examination of correlates by specific races or sexual and gender identities. Recruitment for this study took place from Fall 2020 to Fall 2021 amid the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. As such, 22% of eligible students did not return parental or caregiver consent forms, 22% of parents or caregivers did not consent to participation, and 7% of students did not assent to participation; this could lead to selection bias if students who participated differ from those who did not participate with respect to demographics and nicotine product use behaviors. Additionally, these data were collected in Southern California which may limit generalizability of results to the national United States population; however, previous findings of adolescent tobacco use behaviors in similar California cohorts are highly concordant with findings from nationwide samples.41–44 Because of the cross-sectional nature of the data, we were unable to determine the temporal relationship between oral nicotine product use and e-cigarette and combustible tobacco use. All data were self-reported, and there may be misclassification of nicotine product use or sociodemographic factors. Use of traditional smokeless tobacco products and Food and Drug Administration-approved nicotine replacement therapy was not assessed here. Finally, nicotine gum, lozenges, tablets, and gummies were assessed in one single question, and we were unable to determine which of these oral nicotine products was most prevalent.

CONCLUSION

In this study of Southern California adolescents, flavored non-tobacco oral nicotine products were the second most widely-used nicotine product type and were disproportionately used by certain populations historically impacted by tobacco-related health disparities. Use of these products are not currently tracked in youth national surveillance surveys. Surveillance of non-tobacco oral nicotine product use among adolescents merits priority for national policies designed to protect pediatric populations and promote health equity.

Supplementary Material

WHAT’S KNOWN ON THIS SUBJECT:

Non-tobacco oral nicotine products (eg, nicotine pouches, gum, lozenges, gummies) are increasingly marketed in the United States. It is unknown how common non-tobacco oral nicotine product use is among adolescents, and whether certain groups are at elevated risk of use.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS:

Flavored non-tobacco oral nicotine products were the second most prevalent nicotine product used by adolescents in Southern California. They were disproportionately used by certain racial and ethnic, sexual, or gender minority groups, and those with a history of nicotine use.

FUNDING:

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute and the Food and Drug Administration Center for Tobacco Products (CTP) under Award Number U54CA180905, National Cancer Institute under award number R01CA229617, National Institute on Drug Abuse under award K24DA048160 and K01DA042950, and the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (K01HL148907). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the Food and Drug Administration. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

ABBREVIATIONS

- aOR

adjusted odds ratio

- CI

confidence interval

- OR

odds ratio

- PD

prevalence difference

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES: The authors have indicated they have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Plurphanswat N, Hughes JR, Fagerström K, Rodu B. Initial information on a novel nicotine product. Am J Addict. 2020;29(4):279–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robichaud MO, Seidenberg AB, Byron MJ. Tobacco companies introduce “tobacco-free” nicotine pouches industry watch. Tob Control. 2020;29:145–146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Delnevo CD, Hrywna M, Miller Lo EJ, Wackowski OA. Examining market trends in smokeless tobacco sales in the United States: 2011–2019. Nicotine Tob Res. 2021;23(8):1420–1424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.SAMHSA. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: results from the 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Available at: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/. Accessed January 18, 2022.

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Available at: www.cdc.gov/yrbs. Published 2019. Accessed January 18, 2022.

- 6.United States Department of Health and Human Services. National Institutes of Health. National Institute on Drug Abuse, and United States Department of Health and Human Services. Food and Drug Administration. Center for Tobacco Products. Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study [United States] Public-Use Files. Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research[distributor], 2021-12–16 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Havermans A, Pennings JLA, Hegger I, et al. Awareness, use and perceptions of cigarillos, heated tobacco products and nicotine pouches: A survey among Dutch adolescents and adults. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021;229(Pt B):109136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.England LJ, Bunnell RE, Pechacek TF, Tong VT, McAfee TA. Nicotine and the developing human: a neglected element in the electronic cigarette debate. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(2):286–293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacobsen LK, Krystal JH, Mencl WE, Westerveld M, Frost SJ, Pugh KR. Effects of smoking and smoking abstinence on cognition in adolescent tobacco smokers. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57(1):56–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Musso F, Bettermann F, Vucurevic G, Stoeter P, Konrad A, Winterer G. Smoking impacts on prefrontal attentional network function in young adult brains. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2007;191(1):159–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gilreath TD, Leventhal A, Barrington-Trimis JL, et al. Patterns of alternative tobacco product use: emergence of hookah and e-cigarettes as preferred products amongst youth. J Adolesc Health. 2016;58(2):181–185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park-Lee E, Ren C, Sawdey MD, et al. Notes from the field: e-cigarette use among middle and high school students - National Youth Tobacco Survey, United States, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(39):1387–1389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gentzke AS, Wang TW, Jamal A, et al. Tobacco product use among middle and high school students - United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(50):1881–1888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trends in lifetime prevalence of use of various drugs in Grades 8, 10, and 12. Available at: http://monitoringthefuture.org/data/21data/table1.pdf. Accessed January 9, 2022

- 15.Barrington-Trimis JL, Leventhal AM. Adolescents’ use of “pod mod” e-cigarettes - urgent concerns. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(12):1099–1102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patwardhan S, Fagerström K. The new nicotine pouch category: a tobacco harm reduction tool? Nicotine Tob Res. 2021;2021:1–3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Azzopardi D, Liu C, Murphy J. Chemical characterization of non-tobacco “modern” oral nicotine pouches and their position on the toxicant and risk continuums. Drug Chem Toxicol. 2021;1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Loukas A, Batanova MD, Velazquez CE, et al. Who uses snus? A study of Texas adolescents. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14(5):626–630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dai H, Ramos AK, Faseru B, Hill JL, Sussman SY. Racial disparities of e-cigarette use among US youths: 2014–2019. Am J Public Health. 2021;111(11):2050–2058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harlow AF, Lundberg D, Raifman JR, et al. Association of coming out as lesbian, gay, and bisexual+ and risk of cigarette smoking in a nationally representative sample of youth and young adults. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175(1):56–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Watson RJ, Lewis NM, Fish JN, Goodenow C. Sexual minority youth continue to smoke cigarettes earlier and more often than heterosexuals: Findings from population-based data. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;184:64–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Corliss HL, Wadler BM, Jun HJ, et al. Sexual-orientation disparities in cigarette smoking in a longitudinal cohort study of adolescents. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15(1):213–222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fish JN, Turner B, Phillips G II, Russell ST. Cigarette smoking disparities between sexual minority and heterosexual youth. Pediatrics. 2019;143(4):e20181671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blosnich J, Lee JGL, Horn K. A systematic review of the aetiology of tobacco disparities for sexual minorities. Tob Control. 2013;22(2):66–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Balsam KF, Beadnell B, Riggs KR. Understanding sexual orientation health disparities in smoking: a population-based analysis. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2012;82(4):482–493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krueger EA, Braymiller JL, Barrington-Trimis JL, Cho J, McConnell RS, Leventhal AM. Sexual minority tobacco use disparities across adolescence and the transition to young adulthood. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;217:108298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoffman L, Delahanty J, Johnson SE, Zhao X. Sexual and gender minority cigarette smoking disparities: An analysis of 2016 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System data. Prev Med. 2018;113:109–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dai H Tobacco product use among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adolescents. Pediatrics. 2017;139(4):e20163276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wheldon CW, Kaufman AR, Kasza KA, Moser RP. Tobacco use among adults by sexual orientation: findings from the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health Study. LGBT Health. 2018;5(1):33–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson SE, O’Brien EK, Coleman B, Tessman GK, Hoffman L, Delahanty J. Sexual and gender minority U.S. youth tobacco use: population assessment of tobacco and health (PATH) study wave 3, 2015–2016. Am J Prev Med. 2019;57(2):256–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Day JK, Fish JN, Perez-Brumer A, Hatzenbuehler ML, Russell ST. Transgender youth substance use disparities: results from a population-based sample. J Adolesc Health. 2017;61(6):729–735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Felner JK, Andrzejewski J, Strong D, Kieu T, Ravindran M, Corliss HL. Vaping disparities at the intersection of gender identity and race/ethnicity in a population-based sample of adolescents. Nicotine Tob Res. 2022;24(3):349–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Diamond LM. Gender fluidity and nonbinary gender identities among children and adolescents. Child Dev Perspect. 2020;14(2):110–115 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kloos A, Weller RA, Chan R, Weller EB. Gender differences in adolescent substance abuse. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2009;11(2):120–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kauffman SE, Silver P, Poulin J. Gender differences in attitudes toward alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs. Soc Work. 1997;42(3):231–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Al-Hamdani M, Hopkins DB, Hardardottir A, Davidson M. Perceptions and experiences of vaping among youth and young adult e-cigarette users: considering age, gender, and tobacco use. J Adolesc Health. 2021;68(4):787–793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Benowitz NL, Hukkanen J, Jacob P III. Nicotine chemistry, metabolism, kinetics and biomarkers. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2009;192(192):29–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brose LS, McDermott MS, McNeill A. Heated tobacco products and nicotine pouches: a survey of people with experience of smoking and/or vaping in the UK. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(16):8852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Soneji S, Barrington-Trimis JL, Wills TA, et al. Association between initial use of e-cigarettes and subsequent cigarette smoking among adolescents and young adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(8):788–797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Audrain-McGovern J, Stone MD, Barrington-Trimis J, Unger JB, Leventhal AM. Adolescent e-cigarette, hookah, and conventional cigarette use and subsequent marijuana use. Pediatrics. 2018;142(3):e20173616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Primack BA, Shensa A, Sidani JE, et al. Initiation of traditional cigarette smoking after electronic cigarette use among tobacco-naïve US young adults. Am J Med. 2018;131(4):443.e1–443.e9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Berry KM, Fetterman JL, Benjamin EJ, et al. Association of electronic cigarette use with subsequent initiation of tobacco cigarettes in US youths. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(2):e187794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barrington-Trimis JL, Urman R, Berhane K, et al. E-Cigarettes and future cigarette use. Pediatrics. 2016;138(1):e20160379–e20160379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leventhal AM, Strong DR, Kirkpatrick MG, et al. Association of electronic cigarette use with initiation of combustible tobacco product smoking in early adolescence. JAMA. 2015;314(7):700–707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.