This randomized clinical trial evaluates the efficacy and tolerance of methotrexate alone or combined with low-dose prednisone in patients with chronic and recalcitrant alopecia areata totalis or universalis.

Key Points

Question

What is the efficacy of methotrexate alone or combined with low-dose prednisone in alopecia areata totalis (AT) or universalis (AU), the most severe and disabling types of alopecia areata?

Findings

This double-blind randomized clinical trial including 89 patients showed that while only a few patients with chronic AT or AU achieved complete hair regrowth with methotrexate alone, its combination with low-dose prednisone allowed complete or almost complete regrowth (Severity of Alopecia Tool [SALT] score <10) in 20% to 31.2% of patients.

Meaning

Methotrexate combined with low-dose prednisone may be an inexpensive and effective therapeutic option in AT and AU.

Abstract

Importance

Poor therapeutic results have been reported in patients with alopecia areata totalis (AT) or universalis (AU), the most severe and disabling types of alopecia areata (AA). Methotrexate, an inexpensive treatment, might be effective in AU and AT.

Objective

To evaluate the efficacy and tolerance of methotrexate alone or combined with low-dose prednisone in patients with chronic and recalcitrant AT and AU.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This academic, multicenter, double-blind, randomized clinical trial was conducted at 8 dermatology departments at university hospitals between March 2014 and December 2016 and included adult patients with AT or AU evolving for more than 6 months despite previous topical and systemic treatments. Data analysis was performed from October 2018 to June 2019.

Interventions

Patients were randomized to receive methotrexate (25 mg/wk) or placebo for 6 months. Patients with greater than 25% hair regrowth (HR) at month 6 continued their treatment until month 12. Patients with less than 25% HR were rerandomized: methotrexate plus prednisone (20 mg/d for 3 months and 15 mg/d for 3 months) or methotrexate plus placebo of prednisone.

Main Outcome and Measures

The primary end point assessed on photos by 4 international experts was complete or almost complete HR (Severity of Alopecia Tool [SALT] score <10) at month 12, while receiving methotrexate alone from the start of the study. Main secondary end points were the rate of major (greater than 50%) HR, quality of life, and treatment tolerance.

Results

A total of 89 patients (50 female, 39 male; mean [SD] age, 38.6 [14.3] years) with AT (n = 1) or AU (n = 88) were randomized: methotrexate (n = 45) or placebo (n = 44). At month 12, complete or almost complete HR (SALT score <10) was observed in 1 patient and no patient who received methotrexate alone or placebo, respectively, in 7 of 35 (20.0%; 95% CI, 8.4%-37.0%) patients who received methotrexate (for 6 or 12 months) plus prednisone, including 5 of 16 (31.2%; 95% CI, 11.0%-58.7%) who received methotrexate for 12 months and prednisone for 6 months. A greater improvement in quality of life was observed in patients who achieved a complete response compared with nonresponder patients. Two patients in the methotrexate group discontinued the study because of fatigue and nausea, which were observed in 7 (6.9%) and 14 (13.7%) patients receiving methotrexate, respectively. No severe treatment adverse effect was observed.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this randomized clinical trial, while methotrexate alone mainly allowed partial HR in patients with chronic AT or AU, its combination with low-dose prednisone allowed complete HR in up to 31% of patients. These results seem to be of the same order of magnitude as those recently reported with JAK inhibitors, with a much lower cost.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02037191

Introduction

Alopecia areata totalis (AT) and universalis (AU) are the most severe and disabling types of alopecia areata (AA).1 They are associated with a major alteration of patients’ quality of life, which is close to that observed in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa.2,3,4,5

While many treatments have been successfully proposed in plaque-type AA, very few treatments are effective in chronic types of AT or AU. Both superpotent topical corticosteroids6 and intravenous pulse corticosteroids,7,8,9 phototherapy,10 and topical immunotherapy11 are commonly used in plaque-type AA, but they have a very limited efficacy in chronic types of AT and AU. The efficacy of oral Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors was recently tested in many trials, which, however, included patients with both plaque-type AA and AT or AU.12 They reported a rate of hair regrowth (HR) between 12.0% and 64% depending on the various end points (from Severity of Alopecia Tool [SALT] score of 30 to a SALT score of 10).13,14,15 Topical JAK inhibitors seem less effective.12 Finally, cyclosporine was recently reported to be effective in different types of AA, with 31.7% of patients achieving a greater than 50% HR and 6.3% having a complete HR.16

Since our initial report using methotrexate alone or combined with a low dose of prednisone,17,18 16 studies have been published and analyzed in a meta-analysis.19 Globally, it showed a 44% rate of complete HR, which was mainly observed in adult patients treated with a combination of methotrexate and oral prednisone.19

The aim of the present randomized clinical trial (RCT) was to assess the safety and efficacy of methotrexate alone or combined with a low dose of prednisone for the treatment of patients with chronic AT and AU who previously did not respond to topical and systemic treatments. In particular, the goal of this study was to assess a “reasonable” treatment that could be effective in a certain proportion of patients but above all with good tolerance. This is why we deliberately chose a low dose of prednisone and did not consider a higher dose of prednisone of 0.5 mg/kg/d as in most articles in the literature.20,21,22,23

Methods

Participants

The trial protocol (NCT02037191) and statistical analysis plan are presented in Supplement 1 and Supplement 2, respectively. Inclusion criteria were the following: patients between 18 and 70 years of age with chronic and severe AT or AU, evolving for more than 6 months despite previous topical and systemic treatments, including intravenous pulse corticosteroids, phototherapy, superpotent topical corticosteroids, and topical immunotherapy. Patients who had previously been treated with methotrexate were excluded. All systemic and/or topical treatments had to be stopped for at least 2 months before inclusion in the study. Main exclusion criteria are detailed in the eAppendix in Supplement 3. This trial was approved by The Ethics Committee (CCP Nord Ouest 1). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. This study followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline.

Procedures

This double-blind RCT was conducted in 8 dermatology departments in France between March 2014 and December 2016. The design included 2 successive 6-month treatment phases. Patients in the initial phase were randomly assigned to receive oral methotrexate at a weekly dose of 20 or 25 mg depending on patient’s weight, or a placebo of methotrexate for 6 months. Patients who achieved HR of greater than 25% at month 6 continued their initial treatment at the same dosage until the end of the study at month 12. Patients who had no HR or a HR of less than 25% at month 6 were rerandomized to receive methotrexate (at the same dosage as during the initial phase) combined with oral prednisone (20 mg/d for 3 months then 15 mg/d for 3 months), or methotrexate plus a placebo of prednisone from month 6 to the end of the study at month 12. Treatments were assigned through central computerized randomization.

Outcomes

The primary end point was complete or almost complete HR of terminal hair at month 12 as assessed by 4 international experts (A.T., V.d.M., P.d.V., R.G.), who did not participate in the study. Complete or almost complete HR was defined as the reappearance of terminal hair on a scalp area greater or equal to 90% (SALT score ≤10). All patients who did not achieve a rate of HR of greater than 25% at month 6 and had to be rerandomized to receive methotrexate plus prednisone or placebo from month 6 to month 12 were analyzed as treatment failure for the primary end point, even if they secondarily achieved complete HR at month 12.

Secondary end points were (1) global regrowth assessment, which was evaluated at month 12 by the 4 international experts, study investigators, and patients themselves, and classified in 7 categories: no regrowth, regrowth of nonterminal hair fuzz, or regrowth of terminal hair corresponding to a SALT score of 25 or less, SALT score greater than 25 and less than or equal to 50, SALT score greater than 50 and less than or equal to 75, SALT score greater than 75 and less than or equal to 90, and complete or almost complete regrowth (SALT score >90); (2) relapse rate was defined as the occurrence of 3 or more new patches larger than 2 cm, or a disseminated relapse during the study (under treatment) in patients who initially achieved greater than 25% HR (whatever the initial treatment was); (3) evolution of quality of life as evaluated by the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI),24 Skindex, and the Scalpdex25; and (4) treatment tolerance. Secondary end points were evaluated in both (1) patients who received methotrexate or placebo for 12 months without being rerandomized at month 6 and (2) patients initially assigned to the placebo or methotrexate group who were rerandomized at month 6 to receive either methotrexate plus prednisone or methotrexate plus placebo (Figure 1).

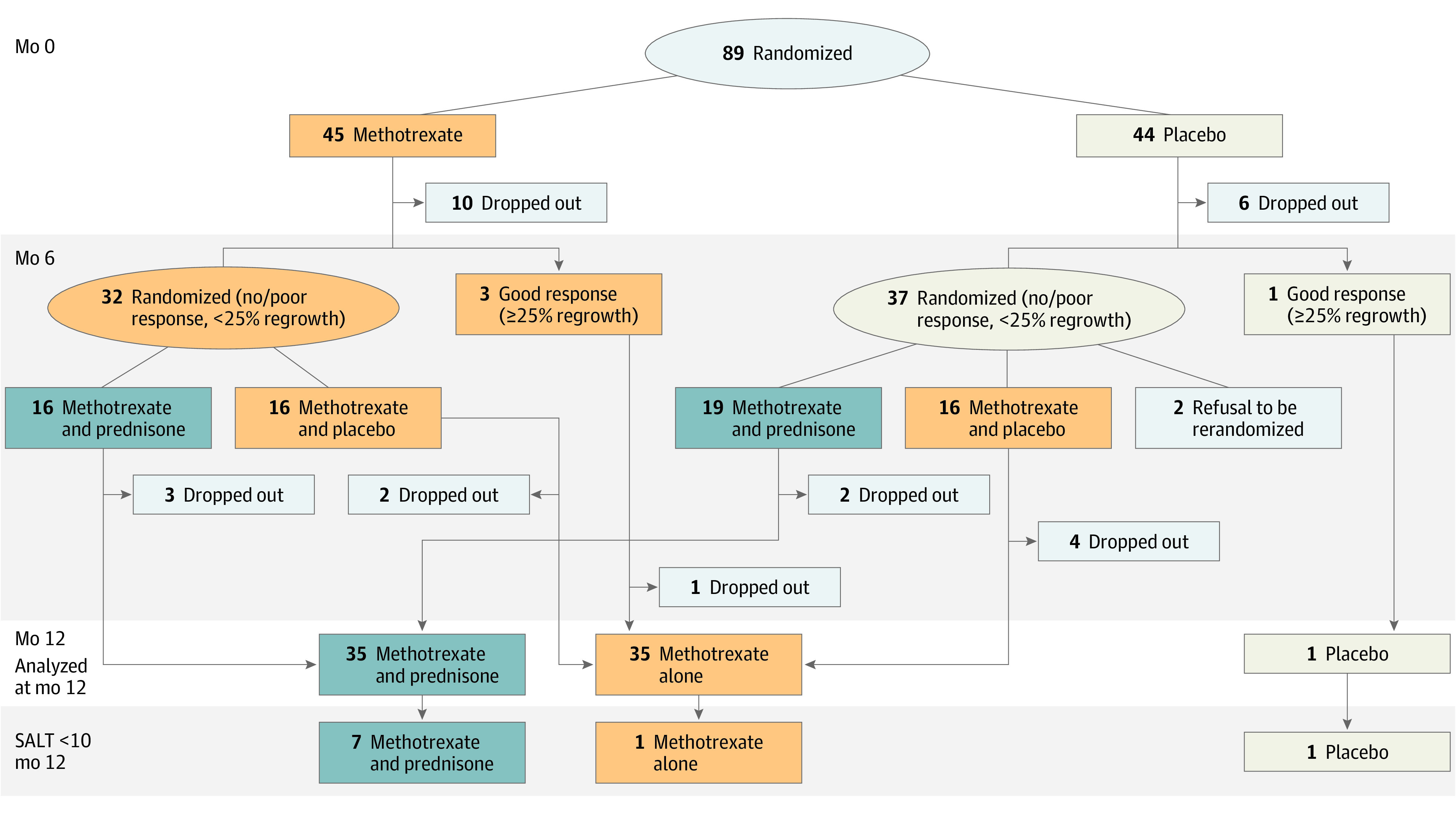

Figure 1. Flowchart of the Study.

Flowchart of the study, showing the number of patients who achieved a complete or almost complete hair regrowth (Severity of Alopecia Tool [SALT] score <10) according to treatment groups: (1) placebo alone for 12 months (n = 1); (2) methotrexate alone (for 6 to 12 months) (n = 35), corresponding to patients who received methotrexate from baseline to month 12 (n = 3), patients who received methotrexate from baseline to month 6 and were rerandomized to receive methotrexate + a placebo of prednisone for 6 months (month 6 to month 12) (n = 16), and patients who received placebo from baseline to month 6 and were rerandomized to receive methotrexate plus a placebo of prednisone for 6 months (month 6 to month 12) (n = 16); and (3) methotrexate plus prednisone (n = 35), corresponding to patients who received methotrexate from baseline to month 6 and were rerandomized at month 6 to receive methotrexate plus prednisone from month 6 to month 12 (n = 16) (these patients thus received methotrexate for 12 months and prednisone for 6 months) and patients who received a placebo of methotrexate from baseline to month 6 and were rerandomized at month 6 to receive methotrexate plus prednisone from month 6 to month 12 (n = 19) (these patients thus received methotrexate for 6 months and prednisone for 6 months).

Hair Regrowth Assessment

A first assessment of HR was performed at month 5 by 4 international experts who received 4 photos of the scalp areas (front, back, left and right sides) and were blinded to patients’ randomization group. They determined if HR was above or below 25% to rerandomize patients with less than 25% HR for the second part of the study. The initial treatment (methotrexate or placebo) was maintained from month 5 to month 6 (second randomization) in patients who had less than 25% HR and until the end of the study at month 12 in patients who achieved a greater than 25% HR at month 5. A second assessment of HR was performed at month 12 concomitantly by the 4 experts, investigators, and patients themselves.

Statistical Analyses

From our preliminary study and the literature,17,18,19 we hypothesized that 30% of patients in the methotrexate group would achieve complete or almost complete regrowth vs 5% of patients receiving placebo. To achieve 80% power relative to this difference at 2-sided .05 level and allowing 10% of dropouts, 90 patients had to be included. Analyses were based on the intent-to-treat (ITT) principle.

Patients who dropped out of the study and those who only had minimal HR at month 6 and were rerandomized for the second part of the study were considered as not having reached the primary end point and were analyzed as treatment failure. The proportion of patients achieving greater than 90% HR (SALT score ≤10) at month 12 while keeping the same treatment assigned at the initial randomization was compared between the 2 treatment groups using Fisher exact test.

Analysis of secondary end points, global regrowth assessment and relapse rate, relied on the same methods. For quantitative outcomes with repeated measurements over time (eg, DLQI, Skindex, or Scalpdex scores), a mixed linear model was used with treatment as a fixed effect and time as a random effect. Reliability of HR assessment performed by international experts, investigators, and patients was assessed through estimation of the weighted κ coefficient and its 95% CI.

All statistical tests used 2-sided .05 level as significance threshold. For quantitative variables, mean (SD) or median (IQR) were reported. All analyses were performed with SAS software, version 9.3 (SAS Institute).

Results

Population of the Study

Eighty-nine patients (50 female, 39 male; mean [SD] age, 38.6 [14.3] years) with AT (n = 1) or AU (n = 88) were included. Baseline characteristics of patients are shown in Table 1. Forty-five patients were assigned to receive methotrexate alone, and 44 received placebo. The 2 groups were well balanced, except for the duration of AA before inclusion, which was longer in the placebo group than in the methotrexate group (mean [SD], 11.9 [11.9] vs 8.0 [10.8] years; P = .01). However, the duration of AT/AU before inclusion was not different between the 2 arms (mean [SD], 2.4 [2.2] vs 1.8 [2.2] years; P = .14).

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of the Population.

| Characteristic | Mean (SD) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methotrexate (n = 45) | Placebo (n = 44) | ||

| Age, y | 41.0 (15.0) | 36.1 (13.2) | .11 |

| Sex, No. (%) | .90 | ||

| Female | 25 (55.6) | 25 (56.8) | |

| Male | 20 (44.4) | 19 (43.2) | |

| Weight, kg | 71.2 (12.9) | 70.2 (13.5) | .70 |

| Previous duration, y | |||

| Of AA | 8.0 (10.8) | 11.9 (11.9) | .01 |

| Of AT/AU | 1.8 (2.2) | 2.4 (2.2) | .14 |

| DLQI score | 7.7 (6.2) | 7.6 (7.4) | .57 |

Abbreviations: AA, alopecia areata; AT, alopecia areata totalis; AU, alopecia areata universalis; DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index.

The flowchart of the study is shown in Figure 1. Sixteen patients (10 in the methotrexate group and 6 in the placebo group) dropped out during the first randomization period, and 14 during the second randomization period (2 patients from the placebo group who did not have HR refused to be rerandomized at month 6, 5 patients in the methotrexate plus prednisone group, 6 patients in the methotrexate plus placebo group, and 1 patient from the initial methotrexate group who had HR of greater than 25% at month 5 and complete HR at month 9 under methotrexate alone, and were then lost to follow-up after the month 9 evaluation) (Figure 1 and Table 2). All these patients were considered as treatment failure in the ITT analysis.

Table 2. Efficacy Results at Month 12 for Subgroups of Patients According to Treatment Regimen.

| Outcome | No. | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Methotrexate alone/methotrexate + placebo of prednisone | Placebo alone (6 mo) | Methotrexate (6 or 12 mo) + prednisone (6 mo) | |

| SALT score ≤10 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| SALT score >10 and ≤25 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| SALT score >25 and ≤50 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| SALT score >50 and ≤75 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| SALT score >75 and ≤90 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| No hair regrowth | 21 | 0 | 9 |

| Dropped out | |||

| During the first randomization period | 10 | 6 | 0 |

| During the second randomization period | 7 | 2 | 5 |

Abbreviation: SALT, Severity of Alopecia Tool.

Primary Outcome

At month 12, 1 patient in the methotrexate group and none in the placebo group had complete HR still receiving the same treatment as at the start of the study (P > .99). Additionally, 1 patient in the methotrexate group had complete HR at the month 9 evaluation but did not complete the month 12 visit.

Secondary Outcomes

Global Hair Regrowth at Month 12

The efficacy results for subgroups of patients depending on their treatment regimen are detailed in Figure 1 and Table 2. Among the 45 patients initially randomized in the methotrexate group, 3 patients had a greater than 25% HR at month 5 and continued to receive methotrexate alone until month 12. One of these 3 patients had complete HR, and 1 had a between 25% and 50% HR at month 12. The remaining patient had a complete HR at month 9 and was then lost to follow-up. Ten patients dropped out, most of them because they did not achieve HR, and 32 patients with less than 25% HR were rerandomized to receive methotrexate and prednisone (n = 16) or methotrexate and placebo of prednisone (n = 16) from month 6 to month 12 (Figure 1).

Among the 44 patients initially randomized in the placebo group, 1 patient had greater than 25% HR at month 6 and continued to receive placebo alone until month 12, 6 patients dropped out due to the absence of HR, and 37 had less than 25% HR. Thirty five of these 37 patients were rerandomized to receive methotrexate and prednisone (n = 19) or methotrexate and placebo (n = 16) from month 6 to month 12. The remaining 2 patients refused to be rerandomized for the second part of the study.

Overall, when pooling patients who continued in their initial randomization group (n = 4) and those who were rerandomized at month 6, 7 of 35 patients (20.0%; 95% CI, 8.4%-37.0%) who received methotrexate alone (without prednisone) had HR, including 1 patient with complete HR (SALT score <10) and 1 patient with complete HR at month 9 who could not be evaluated at month 12.

Among the 35 patients who received methotrexate (for 6 or 12 months) and prednisone for 6 months, 21 patients (60.0%; 95% CI, 42.1%-76.1%) had HR including complete HR (SALT score <10) in 7 patients (20.0%; 95% CI, 8.4%-37.0%).

Finally, when considering the 16 patients who received methotrexate for 12 months (patients initially randomized to the methotrexate group) and who received oral prednisone from month 6 to month 12 (in addition to methotrexate), complete HR (SALT score <10) was observed in 5 of 16 patients (31.2%; 95% CI, 11.0%-58.7%) (Figure 1).

Table 2 presents the detailed SALT scores of patients who received placebo, methotrexate alone, and the combination of methotrexate and prednisone.

Beginning of Hair Regrowth

A rate of greater than 25% of HR (that we considered as a beginning of HR) was first observed at the month-5 assessment after the start of treatment in all 3 patients who had complete or greater than 50% HR with methotrexate alone (including the 1 patient who had total HR at month 9 and did not attend the month-12 evaluation), and at the month-9 evaluation (corresponding to 3 months after the second randomization) in 11 of the 13 patients treated with the combination of methotrexate and prednisone.

Relapse Rate

A relapse occurred under treatment in 1 of the 36 patients who initially received placebo and had HR. The relapse occurred between month 9 and month 12 while the patient was continuing to receive placebo.

Quality of Life

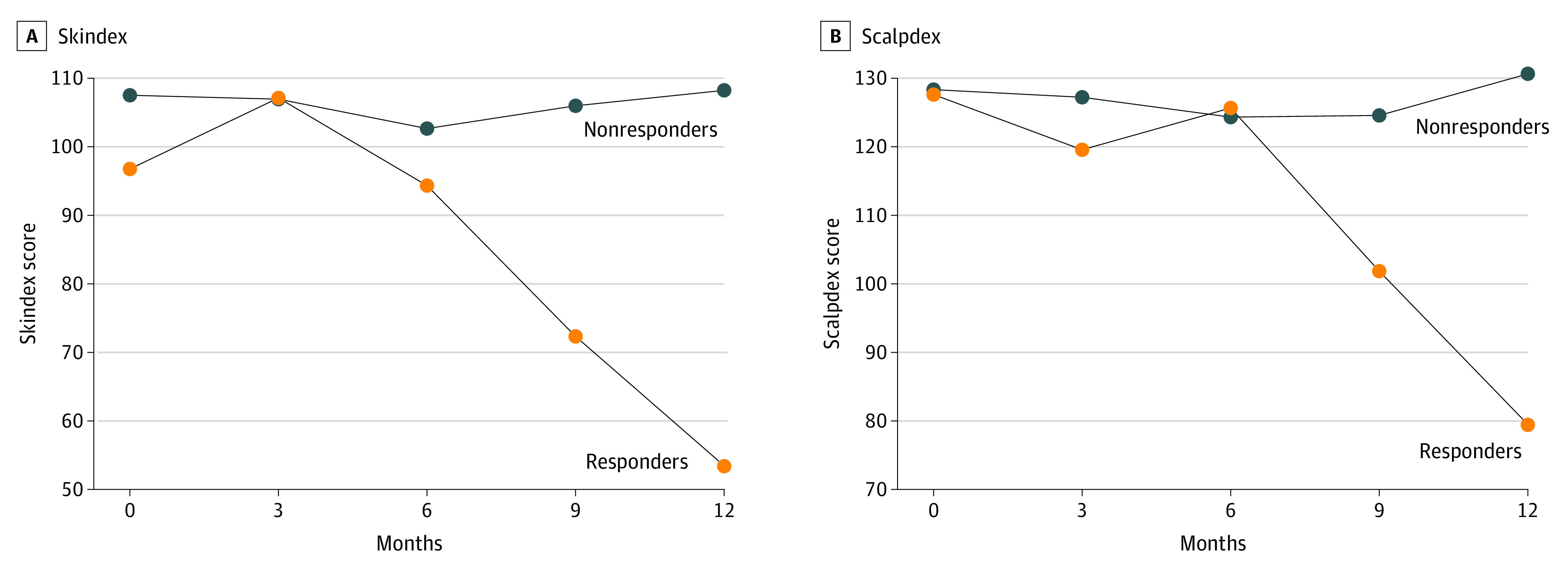

No statistical difference in the evolution of DLQI, Skindex, and Scalpdex scores was observed between the 2 groups. Patients with complete/almost complete HR (SALT score <10) had a greater improvement of DLQI, Skindex, and Scalpdex quality-of-life scores than nonresponder patients (P = .05, P = .03, and P = .03, respectively) (supporting data in Figure 2; eTable in Supplement 3).

Figure 2. Evolution of the Quality of Life.

Evolution of the quality of life as assessed by Skindex and Scalpdex in responders (patients who achieved complete/almost complete hair regrowth, Severity of Alopecia Tool score <10) vs patients who did not.

Treatment Tolerance

A total of 103 grade 1 to 2 adverse events (AEs) were recorded in 45 patients (Table 3). No severe treatment-related AE occurred during the study. Nonsevere AEs were observed in 2 patients receiving placebo (0.007 AE per patient and month of exposure), 27 patients who received methotrexate alone (0.02 AE per patient and month of exposure), and 16 patients who received methotrexate plus prednisone (0.03 AE per patient and month of exposure). Two patients in the methotrexate group discontinued the study because of fatigue and nausea.

Table 3. Distribution of Grade 1-2 Adverse Events (n = 103) in Patients Treated With Methotrexate Alone, Methotrexate Plus Prednisone, and Placebo.

| Type of adverse events | No. (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 103) | Methotrexate (n = 68) | Methotrexate + prednisone (n = 33) | Placebo alone (6 mo) (n = 2) | |

| Blood abnormalitiesa | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.5) | 0 | 0 |

| Headache | 4 (3.9) | 4 (5.9) | 0 | 0 |

| Mucocutaneousb | 17 (16.5) | 12 (17.7) | 5 (15.1) | 0 |

| Infectionc | 26 (25.2) | 16 (23.5) | 8 (24.2) | 2 (100) |

| Musculoskeletald | 6 (5.8) | 4 (5.9) | 2 (6.1) | 0 |

| Nausea/vomiting | 14 (13.6) | 9 (13.2) | 5 (15.2) | 0 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1 (1.0) | 0 | 1 (3.0) | |

| Weight gain | 1 (1.0) | 0 | 1 (3.0) | 0 |

| Liver abnormalitiese | 6 (5.8) | 3 (4.4) | 3 (9.1) | 0 |

| Gastrointestinalf | 11 (10.6) | 9 (13.2) | 2 (6.1) | 0 |

| Dentalg | 4 (3.9) | 1 (1.5) | 3 (9.1) | 0 |

| Asthma | 3 (2.9) | 3 (4.4) | 0 | 0 |

| Fatigue | 7 (6.8) | 4 (5.9) | 3 (9.1) | 0 |

| Otherh | 2 (1.9) | 2 (2.9) | 0 | 0 |

Blood abnormalities: lymphopenia.

Mucocutaneous: dyshidrosis, warts, seborrhea, folliculitis, vitiligo, pruritus, oral ulcers, gingivitis, eczema, sebaceous cyst.

Infection: benign ear, nose, or throat infection, zona, labial herpes simplex, vaginitis, cutaneous abscess, flu, gastroenteritis, blepharitis.

Musculoskeletal: arthrosis, muscular pain, lumbago, tendinitis, gonalgia.

Liver abnormalities: cytolysis, elevated γ-glutamyltransferase.

Gastrointestinal: stomach pain, rectorrhagia, diarrhea, constipation, bloating.

Dental: tooth infection, dental cyst, tooth extraction.

Other: degenerative cervical myelopathy, metrorrhagia.

Main adverse effects in the methotrexate alone group were fatigue, nausea, abdominal pain, and benign infection. One patient in the methotrexate group had transient lymphopenia (980/μL; to convert to ×109/L, multiply by 0.001), and 6 patients had a transient elevation of liver enzymes (3 patients in the methotrexate alone group and 3 in the methotrexate plus prednisone group). These blood abnormalities spontaneously resolved without stopping treatments. Table 3 shows that the distribution of grade 1 to 2 AE was very close between patients treated with methotrexate alone or the combination of methotrexate and prednisone.

Interrater Concordance

Finally, a high interrater concordance for HR assessment was observed between experts, investigators, and patients: Cohen κ coefficient investigators/patients: 0.96 (95% CI, 0.92-0.96), κ coefficient investigators/experts: 0.81 (95% CI, 0.74-0.89); and κ coefficient patients/experts: 0.80 (95% CI, 0.72-0.89).

Discussion

Unlike most studies on severe types of AA, which included a significant proportion of patients with plaque-type AA, this academic double-blind RCT only included patients with AT and AU. Indeed, plaque-type AA is known to be less severe than AT and AU, whereas very poor therapeutic results have been reported in these later patients who have the highest therapeutic need. Our study mainly showed that while methotrexate alone did not demonstrate sufficient efficacy in AT and AU, the combination of methotrexate plus low-dose prednisone allowed to achieve complete or almost complete HR in up to 31% of patients. These findings are robust, as HR was evaluated by 4 blinded international experts whose assessment was highly consistent with that of the investigators and patients. These results are also in accordance with a meta-analysis of 419 patients from 16 studies, which reported a 44.7% rate of complete HR.19 A start of HR was observed 3 months after the start of the combination therapy in most patients who had HR, which corresponded to a shorter delay than that observed when using methotrexate alone.

Our results are in fact difficult to compare with those from recent studies that assessed the efficacy of JAK inhibitors, since all these studies included patients with plaque-type AA in addition to patients with AT or AU. Indeed, only 50% of patients included in the recent RCT testing baricitinib in AA had AT or AU, whereas 50% had a plaque-type AA.15 Additionally, patients with a long duration of AA were included only if they had a previous episode of HR spontaneously or under treatment, while patients in the current trial were selected based because they had chronic and recalcitrant AA without HR despite previous local and systemic treatments. Despite the fact that the statistical analyses in all the trials testing JAK inhibitors in AA were mostly performed on the whole population of patients with plaque type and AT and AU, the last study by King et al15 reported almost complete HR at week 36 (SALT score <10) in 4.7% and 13.9% of patients treated with baricitinib, 2 mg and 4 mg, respectively. In an extension phase of the study Taylor et al26 recently reported rates of 15.3% and 28.9% of patients who achieved a SALT score less than 10 at week 52 among the whole population of patients with severe (plaque type) and very severe AA. These results seem to be of the same order of magnitude as the 20% rate of complete HR observed in the present study in patients with exclusive AT or AU (no plaque-type AA) who received methotrexate (for 6 months plus prednisone for 6 months), which increased up to 31% in those who received methotrexate for 12 months (from the first randomization) combined with prednisone for 6 months.

Our results question the respective roles of methotrexate and corticosteroids, since most patients who achieved major HR were treated with the combination therapy. The therapeutic effect of methotrexate in our study is suggested by the efficacy of this combined treatment despite the fact that we deliberately chose a rather low 20 and then 15 mg/d dose of prednisone, unlike most studies of the literature, which tested a 2-fold higher dose of 0.5 mg/kg/d,20,21,22,23 and the fact that according to our clinical experience, methotrexate alone is regularly effective in plaque-type AA. In addition, it is likely that methotrexate has a steroid-sparing effect as in many other autoimmune diseases, allowing a tapering of corticosteroid doses. Indeed, in clinical practice, after obtaining HR, the prednisone dose is progressively tapered from 15 mg/d to a dose of between 5 and 10 mg/d, to avoid long-term corticosteroid adverse effects. This is a limitation of this treatment in the long term, since some patients are corticosteroid dependent.

To assess this evolution in the long term, we recorded the follow-up of 7 of the 8 patients who achieved complete HR during the study. After a mean follow-up of 70.3 months, 5 of 7 patients still had HR between a SALT score of 40 and 0. Three patients had stopped treatment, while the 4 patients who were still treated took a mean dose of prednisone and methotrexate of 8.7 mg/d and 11.6 mg/wk, respectively. Two adverse effects were observed: 1 case of osteoporosis, and 1 case of Cushingoid face.

Adverse events were well-known adverse effects of methotrexate, which mainly included fatigue, nausea, and abdominal pain. Infections occurred in 23.5% of patients treated with methotrexate alone and 24.2% of those treated with methotrexate plus prednisone and were benign in all cases.

Importantly, the combination of prednisone with methotrexate was rather well tolerated, since corticosteroid-related adverse effects were rarely observed. This good tolerance was likely related to the low dose of prednisone used. Additionally, the safety data of methotrexate are particularly well known, both in the short term and long term.

Limitations

This study has limitations. Thirty patients (33.7%) dropped out of the study, which can be considered as a limitation of the study. However, all these patients were analyzed as treatment failure in the ITT analysis, which is in accordance with the fact that most of these patients dropped out because they did not have HR. Additionally, the tertiary care center of Saint Louis Hospital was likely responsible for a selection bias, since this center, which manages patients with the most severe AT and AU, constituted 58.7% of the population in this trial with a rate of treatment failure at month 6 of 60.9% vs 41.7% in the other centers.

Conclusions

Overall, this RCT has shown that the combination of methotrexate and low-dose prednisone can be considered as a therapeutic option in patients with recalcitrant types of AT or AU, even after the failure of previous systemic treatments, since it allowed complete HR in 20% to 31% of patients.

Trial Protocol

Statistical Analysis Plan

eAppendix. Exclusion criteria

eTable. QOL of responders (patients who achieved complete/almost complete HR (< SALT 10) versus patients who did not

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Mirzoyev SA, Schrum AG, Davis MDP, Torgerson RR. Lifetime incidence risk of alopecia areata estimated at 2.1% by Rochester Epidemiology Project, 1990-2009. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134(4):1141-1142. doi: 10.1038/jid.2013.464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolkenstein P, Loundou A, Barrau K, Auquier P, Revuz J; Quality of Life Group of the French Society of Dermatology . Quality of life impairment in hidradenitis suppurativa: a study of 61 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56(4):621-623. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.08.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dubois M, Baumstarck-Barrau K, Gaudy-Marqueste C, et al. ; Quality of Life Group of the French Society of Dermatology . Quality of life in alopecia areata: a study of 60 cases. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130(12):2830-2833. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Güleç AT, Tanriverdi N, Dürü C, Saray Y, Akçali C. The role of psychological factors in alopecia areata and the impact of the disease on the quality of life. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43(5):352-356. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02028.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gupta MA, Gupta AK. Depression and suicidal ideation in dermatology patients with acne, alopecia areata, atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139(5):846-850. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02511.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tosti A, Piraccini BM, Pazzaglia M, Vincenzi C. Clobetasol propionate 0.05% under occlusion in the treatment of alopecia totalis/universalis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(1):96-98. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2003.423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shreberk-Hassidim R, Ramot Y, Gilula Z, Zlotogorski A. A systematic review of pulse steroid therapy for alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(2):372-4.e1, 5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.09.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedli A, Labarthe MP, Engelhardt E, Feldmann R, Salomon D, Saurat JH. Pulse methylprednisolone therapy for severe alopecia areata: an open prospective study of 45 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39(4, pt 1):597-602. doi: 10.1016/S0190-9622(98)70009-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kar BR, Handa S, Dogra S, Kumar B. Placebo-controlled oral pulse prednisolone therapy in alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52(2):287-290. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.10.873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.El-Mofty M, Rasheed H, El-Eishy N, et al. A clinical and immunological study of phototoxic regimen of ultraviolet A for treatment of alopecia areata: a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Dermatolog Treat. 2019;30(6):582-587. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2018.1543847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee S, Kim BJ, Lee YB, Lee W-S. Hair regrowth outcomes of contact immunotherapy for patients with alopecia areata: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(10):1145-1151. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.2312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Phan K, Sebaratnam DF. JAK inhibitors for alopecia areata: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33(5):850-856. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guo L, Feng S, Sun B, Jiang X, Liu Y. Benefit and risk profile of tofacitinib for the treatment of alopecia areata: a systemic review and meta-analysis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(1):192-201. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.King B, Guttman-Yassky E, Peeva E, et al. A phase 2a randomized, placebo-controlled study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of the oral Janus kinase inhibitors ritlecitinib and brepocitinib in alopecia areata: 24-week results. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85(2):379-387. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2021.03.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.King B, Ohyama M, Kwon O, et al. ; BRAVE-AA Investigators . Two phase 3 trials of baricitinib for alopecia areata. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(18):1687-1699. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2110343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lai VWY, Chen G, Gin D, Sinclair R. Cyclosporine for moderate-to-severe alopecia areata: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial of efficacy and safety. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81(3):694-701. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.04.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joly P. The use of methotrexate alone or in combination with low doses of oral corticosteroids in the treatment of alopecia totalis or universalis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(4):632-636. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chartaux E, Joly P. Long-term follow-up of the efficacy of methotrexate alone or in combination with low doses of oral corticosteroids in the treatment of alopecia areata totalis or universalis. Article in French. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2010;137(8-9):507-513. doi: 10.1016/j.annder.2010.06.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Phan K, Ramachandran V, Sebaratnam DF. Methotrexate for alopecia areata: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(1):120-127.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.06.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kurosawa M, Nakagawa S, Mizuashi M, et al. A comparison of the efficacy, relapse rate and side effects among three modalities of systemic corticosteroid therapy for alopecia areata. Dermatology. 2006;212(4):361-365. doi: 10.1159/000092287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kern F, Hoffman WH, Hambrick GW Jr, Blizzard RM. Alopecia areata: immunologic studies and treatment with prednisone. Arch Dermatol. 1973;107(3):407-412. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1973.01620180061019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Winter RJ, Kern F, Blizzard RM. Prednisone therapy for alopecia areata: a follow-up report. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112(11):1549-1552. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1976.01630350025006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olsen EA, Carson SC, Turney EA. Systemic steroids with or without 2% topical minoxidil in the treatment of alopecia areata. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128(11):1467-1473. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1992.01680210045005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Finlay AY. Skin disease disability: measuring its magnitude. Keio J Med. 1998;47(3):131-134. doi: 10.2302/kjm.47.131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen SC, Yeung J, Chren M-M. Scalpdex: a quality-of-life instrument for scalp dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138(6):803-807. doi: 10.1001/archderm.138.6.803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taylor SC, Korman NJ, Tsai TF. Efficacy of baricitinib in patients with various degrees of alopecia areata severity: results from BRAVE-AA1 and BRAVE-AA2 [poster abstract 33766]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87(3)(suppl):AB52. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2022.06.243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

Statistical Analysis Plan

eAppendix. Exclusion criteria

eTable. QOL of responders (patients who achieved complete/almost complete HR (< SALT 10) versus patients who did not

Data Sharing Statement