Abstract

Background:

We sought to characterize if prehospital transfer origin from the scene of injury (SCENE) or from a referral emergency department (REF) alters the survival benefit attributable to prehospital plasma resuscitation in patients at risk of hemorrhagic shock.

Methods:

We performed a secondary analysis of data from a recently completed prehospital plasma clinical trial. All of the enrolled patients from either the SCENE or REF groups were included. The demographics, injury characteristics, shock severity and resuscitation needs were compared. The primary outcome was a 30-day mortality. Kaplan-Meier analysis and Cox-hazard regression were used to characterize the independent survival benefits of prehospital plasma for transport origin groups.

Results:

Of the 501 enrolled patients, the REF group patients (n = 111) accounted for 22% with the remaining (n = 390) originating from the scene. The SCENE group patients had higher injury severity and were more likely intubated prehospital. The REF group patients had longer prehospital times and received greater prehospital crystalloid and blood products. Kaplan-Meier analysis revealed a significant 30-day survival benefit associated with prehospital plasma in the SCENE group (P < .01) with no difference found in the REF group patients (P = .36). The Cox-regression verified after controlling for relevant confounders that prehospital plasma was independently associated with a 30-day survival in the SCENE group patients (hazard ratio 0.59; 95% confidence interval 0.39–0.89; P = .01) with no significant relationship found in the REF group patients (hazard ratio 1.03, 95% confidence interval 0.4–3.0).

Conclusion:

Important differences across the SCENE and REF cohorts exist that are essential to understand when planning prehospital studies. Prehospital plasma is associated with a survival benefit primarily in SCENE group patients. The results are exploratory but suggest transfer origin may be an important determinant of prehospital plasma benefit.

Introduction

Hemorrhage remains a leading cause of preventable death after a traumatic injury.1,2 Recent clinical trials following injury have demonstrated the importance of the prehospital phase of care interventions that maximize survival benefits for those at risk of hemorrhage.3–8 Early plasma resuscitation has been shown to safely reduce mortality when provided during air medical transport to definitive trauma care using simple, pragmatic vital sign criteria.6 Further characterization of the survival advantages associated with prehospital plasma has demonstrated more robust outcome benefits in those with severe polytrauma, including traumatic brain injury.4,9–12 Having a complete understanding of the most relevant injured patient populations who benefit most from prehospital plasma is essential, allowing resources to be directed to those most appropriate.

The trauma patients admitted to tertiary and quaternary trauma centers arrive via air medical transport mainly from either the scene of injury or an outside emergency department that is unable to provide definitive trauma care.13–15 Although injured patients from either of these transfer origins may present to definitive trauma care with similar demographics and injury patterns, these distinct patient populations may respond differently to prehospital interventions because of differences in treatments, survival biases, and the respective timing of interventions relative to the time of injury.13,16–18

We performed a secondary analysis of data from a recently completed prehospital plasma clinical trial to determine if transfer origin from the scene of injury (SCENE) or from a referral hospital (REF) alters the beneficial outcome effects of prehospital plasma in patients at risk of hemorrhagic shock. We hypothesized that transfer origin would be an important moderator of prehospital plasma survival, with survival being strongest in those who arrive from scene of injury.

Methods

The current study was a post hoc secondary analysis of data derived from a recently completed multicenter prehospital plasma clinical trial.6 The PAMPer trial was a pragmatic, multicenter, Phase 3, cluster randomized clinical superiority trial designed to test the effect of administering plasma to severely injured trauma patients on air ambulances before arrival to definitive trauma care. The original study was approved under an Emergency Exception From Informed Consent protocol from the Human Research Protection Office of the US Army Medical Research and Material Command and by the appropriate Institutional Review Boards as previously described.6

The patients with blunt or penetrating injuries were eligible for enrollment if they met either of the following criteria at any time before arrival at the participating study center: (1) ≥1 episode of systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg and heart rate >108 beats/min, or (2) any episode of systolic blood pressure <70 mmHg. The exclusion criteria included prisoner status, known pregnancy, isolated penetrating injury to the head, ground-level fall, asystole or cardiopulmonary resuscitation (>5 minutes), or those wearing opt-out bracelets. The selected inclusion criteria were derived from prior prehospital interventional trials.19

Enrolled patients received 2 units of either group AB or group A with a low anti-B antibody titer (<1:100) thawed plasma or received standard prehospital air medical care. Standard care consisted of crystalloid-based resuscitation for 14 of the 27 participating air medical bases. The air transport teams at the other 13 participating air medical bases also carried 2 units of universal donor red blood cells on all flights as part of their standard trauma resuscitation care. Randomization was at the level of the air medical base for 1-month periods. Importantly, prehospital plasma was administered before other resuscitative fluids once the patient met all inclusion and no exclusion criteria. All of the study participants who were enrolled in the primary study were eligible and included in the current secondary analysis. The outcome assessors for the trial were blinded to the prehospital intervention received. No additional data was collected, and no further records were evaluated for the current analysis.6

For the current secondary analysis, air medical transfer origin was classified as either being transported from the scene (SCENE group) of their injury or from an outside referral emergency department (REF group). The prehospital time period for the overall PAMPer study and the current secondary analysis includes the time from qualifying vital sign inclusion criteria (enrollment) to participating trauma center arrival. All of the measurements, resuscitation volumes, and variables during this time period, from trial enrollment to trauma center arrival, were categorized as occurring during the prehospital phase of care inclusion, irrespective of transfer origin. Importantly, the patients who were admitted to an outside hospital were excluded from the original trial enrollment. The specific time of injury was unable to be obtained. The primary outcome for the current analysis was 30-day mortality. The secondary outcomes of interest included 24-hour mortality, trauma resuscitation and transfusion requirements, intensive care unit-based organ dysfunction and infectious outcomes, and hemostasis and/or coagulation measurements. All analyses were carried out in the intention-to-treat randomized patients. Causes of death were adjudicated by the site principal investigators in a rolling fashion over the enrollment time period.

We first evaluated the treatment effect of prehospital plasma on 30-day mortality across SCENE and REF patient groups using a Cox proportional-hazard model. The plasma and transfer origin interaction was assessed for statistical significance accounting for confounders.

We then performed a Kaplan-Meier survival analysis comparing prehospital plasma versus standard care patients stratified across transfer origin groups (SCENE and REF), for both 24-hour and 30-day mortality, using log-rank comparison. To verify these unadjusted findings, we performed a multivariate analysis of survival with the use of a Cox proportional-hazard model to evaluate the treatment effect (plasma versus standard care), with adjustment for important confounders for 24-hour and 30-day mortality. The model was generated for the primary outcome in patients with a SCENE transfer origin.

All of the covariates statistically significant on univariate analysis were assessed. In the final regression model, only the covariates with a P < 0.1 and/or that altered the hazard ratio (HR) for the treatment of interested by >5% were used to prevent overfitting of the model. An identical model was used for all Cox-regression analyses. The model included prehospital crystalloid, prehospital transport time (minutes), injury severity (Injury Severity Score [ISS]), and prehospital Glasgow Coma Scale. The models passed the proportional-hazards assumption on the basis of Schoenfeld residuals. Descriptive statistics characterized the demographics and injuries of the patients and outcomes of interest. The categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages and tested using the χ2 analysis. The continuous variables were expressed as medians and IQRs and were tested using Student’s t test or Mann-Whitney U test as appropriate. All data were analyzed using Stata 17.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX).

Results

The original PAMPer trial enrolled a total of 501 patients (230 randomized to the plasma group and 271 randomized to the standard care group), all of whom met the current secondary analysis inclusion criteria. The randomized plasma and standard care arms of the primary trial were clinically similar in injury characteristics and shock parameters. The enrolled patients overall had a median ISS of 22 (IQR 13–30), a median initial Glasgow Coma Scale score of 11 (IQR 3–15), and an overall 30-day mortality rate of 29%. Importantly, the patients in the standard care arm were more likely to receive prehospital packed red blood cells and higher volumes of crystalloids before arrival due to the absence of plasma resuscitation capabilities in the standard care arm.

The current study population was composed of 390 patients with an air medical transfer origin from the scene of injury (SCENE; 78%) and 111 patients transferred from an outside referral emergency department (REF; 22%). Randomization to plasma or standard of care was equally distributed across each transfer origin group (SCENE: 45.6% randomized to plasma versus REF: 46.5% randomized to plasma). The SCENE and REF group patients were clinically similar in demographics and mechanisms of injury and presenting shock characteristics (Table I). The REF group patients received a greater volume of prehospital crystalloid resuscitation, were more likely to receive prehospital red cell transfusion, were less commonly intubated prehospital, and spent greater time in the prehospital phase of care before definitive trauma center arrival. The REF group patients had an overall lower injury severity, primarily due to lower head and/or neck and extremity injuries, and had lower unadjusted 24-hour and 30-day mortality. Trauma resuscitation requirement measurements included units of red cells, plasma, platelet units transfused, total blood component units transfused, and crystalloid resuscitation volumes in the initial 6 and 24 hours. There were no significant differences between resuscitation requirements at 6 or 24 hours based on transfer origin (Table II).

Table I.

Characteristics of Patients Stratified by Air Medical Transfer Origin (SCENE Versus REF)

| SCENE |

REF |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 390 | N = 111 | ||

| Age (y) median (IQR) | 44 (29–58) | 48 (30–66) | .25 |

| Male, n (%) | 288 (73.8) | 76 (68.5) | .26 |

| Race, n (%) | .01* | ||

| White | 347 (89.0) | 88 (79.3) | |

| African American | 25 (6.4) | 18 (16.2) | |

| Asian | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Other | 5 (1.3) | 3 (2.7) | |

| Unknown | 12 (3.1) | 2 (1.8) | |

| Hispanic, n (%) | 13 (3.3) | 2 (1.8) | .40 |

| BMI, median (IQR) | 31.6 (25.6–151.4) | 30.1 (26.4–43.2) | .29 |

| Blunt mechanism of injury, n (%) | .01* | ||

| Fall | 21 (6.3) | 14 (17.3) | |

| Machinery | 5 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| MVC-occupant | 183 (55.1) | 43 (53.1) | |

| MVC-motorcyclist | 67 (20.2) | 8 (9.9) | |

| MVC-cyclist | 6 (1.8) | 1 (1.2) | |

| MVC-pedestrian | 18 (5.4) | 3 (3.7) | |

| MVC-unknown | 2 (0.6) | 1 (1.2) | |

| Struck by or against | 16 (4.8) | 3 (3.7) | |

| Other | 14 (4.2) | 8 (9.9) | |

| Penetrating mechanism of injury, n (%) | .85 | ||

| Firearm | 33 (52) | 18 (56) | |

| Impalement | 6 (10) | 2 (6) | |

| Stabbing | 24 (38) | 12 (38) | |

| Prehospital crystalloid, median (IQR), mL | 581 (0–1200) | 1000 (0–2417) | < .01* |

| Received prehospital red blood cells, n (%) | 123 (31.5%) | 51 (45.9%) | < .01* |

| Initial GCS was <8, n (%) | 177 (45.4%) | 55 (49.5%) | .44 |

| Required prehospital intubation, n (%) | 219 (56.2%) | 37 (33.3%) | < .01* |

| Required prehospital CPR, n (%) | 24 (6.2%) | 7 (6.3%) | .95 |

| Prehospital systolic blood pressure, median (IQR), mmhg | 70 (62–81) | 69 (64–82) | .76 |

| Prehospital heart rate, median (IQR) | 106 (90–123) | 105 (87–120) | .34 |

| Prehospital time from randomization, median (IQR), min | 39 (31–49) | 52 (41–71) | < .01* |

| AIS head >2, n (%) | 156 (40.0) | 34 (30.6) | .07 |

| AIS face >2, n (%) | 17 (4.4) | 4 (3.6) | .73 |

| AIS chest >2, n (%) | 209 (53.6) | 56 (50.5) | .56 |

| AIS abdomen >2, n (%) | 96 (24.6) | 34 (30.6) | .20 |

| AIS extremity >2, n (%) | 139 (35.6) | 27 (24.3) | .03* |

| AIS external >2, n (%) | 7 (1.8) | 6 (5.4) | .03* |

| ISS, median (IQR) | 22 (14–33) | 17 (10–26) | < .01* |

| Traumatic brain injury on initial CT imaging, n (%) | 132 (33.8) | 34 (30.6) | .53 |

| Arrival lactate, median (IQR), mmol/L† | 3.6 (2.4–5.3) | 4.2 (2.3–6.5) | .36 |

| Arrival hemoglobin, median (IQR), g/dL‡ | 11.5 (9.7–13.1) | 11.7 (9.5–13.3) | .78 |

| 24-h mortality, n (%) | 80 (20.5) | 12 (10.8) | .02* |

| 30-d mortality, n (%) | 116 (29.7) | 24 (21.6) | .07 |

| Randomized to prehospital plasma group, n (%) | 178 (45.6) | 52 (46.8) | .82 |

AIS, Abbreviated Injury Scale; BMI, body mass index; CT, computed tomography; GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; ISS, Injury Severity Score; MVC, motor vehicle collision; REF, transfer origin from a referral emergency department; SCENE, transfer origin from the scene of injury.

P < .05

Lactate measurements unavailable for 200 SCENE patients and 42 REF patients.

Hemoglobin measurements unavailable for 38 SCENE patients and 10 REF patients’

Table II.

Trauma resuscitation requirements at 6 hours and 24 hours stratified by air medical transfer origin (SCENE versus REF)

| SCENE |

REF |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 390 | N = 111 | ||

| Trauma resuscitation in initial 6 h | |||

| Red cell transfusion, median (IQR), units | 3.0 (0.8–7.0) | 2.0 (0.0–6.0) | .14 |

| Plasma transfusion, median (IQR), units | 0.0 (0.0–3.0) | 0.0 (0.0–2.0) | .57 |

| Platelet transfusion, median (IQR), units | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | .19 |

| Total blood component transfusion, median (IQR), units | 4.0 (1.0, 11.0) | 2.0 (0.0–10.0) | .15 |

| Crystalloid, median (IQR), mLs | 2,700 (1,485–4,098) | 3,200 (1,500–4,996) | .11 |

| Trauma resuscitation in initial 24 h | |||

| Red cell transfusion, median (IQR), units | 4.0 (1.0–8.0) | 3.0 (0.0–6.0) | .14 |

| Plasma transfusion, median (IQR), units | 0.0 (0.0–4.0) | 0.0 (0.0–3.0) | .54 |

| Platelet transfusion, median (IQR), units | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | .33 |

| Total blood component transfusion, median (IQR), units | 4.0 (1.0–13.0) | 3.0 (1.0–11.0) | .25 |

| Crystalloid, median (IQR), mLs | 4,434 (2,687–6,635) | 4,500 (2,000–6,664) | .63 |

REF, transfer origin from a referral emergency department; SCENE, transfer origin from the scene of injury.

Unadjusted mortality comparison across standard care and plasma groups stratified by transfer origin demonstrated significant differences in the SCENE group patients between standard care and plasma groups for both early and 30-day mortality. No significant differences across treatment groups were found for REF group patients (Table III). Based on this, we then tested to determine if the survival benefit of prehospital plasma was affected or altered by transfer origin. Using a Cox proportional-hazard model, we tested for and found a significant interaction between randomization group and transfer origin (P = .03).

Table III.

Unadjusted 24-hour and 30-day mortality across randomized arms stratified by transfer origin (SCENE versus REF)

| SCENE |

REF |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard care N = 212 | Plasma N = 178 | P value | Standard care N = 59 | Plasma N = 52 | P value | |

| 24-h mortality, n (%) | 55 (25.9) | 25 (14.0) | < .01* | 5 (8.5) | 7 (13.5) | .40 |

| 30-d mortality, n (%) | 76 (35.8) | 40 (22.5) | < .01* | 13 (25.0) | 11 (18.6) | .42 |

REF, transfer origin from a referral emergency department; SCENE, transfer origin from the scene of injury.

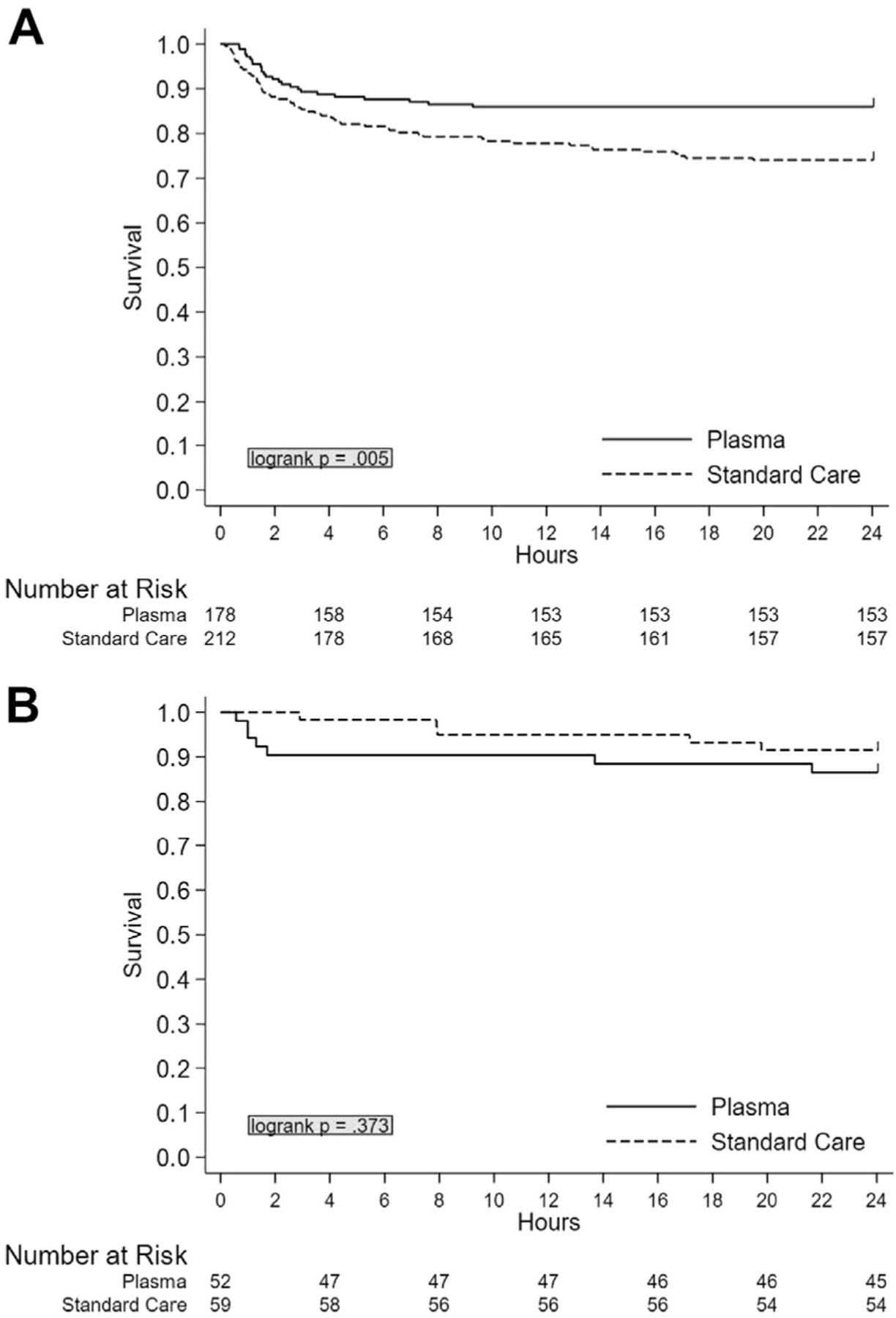

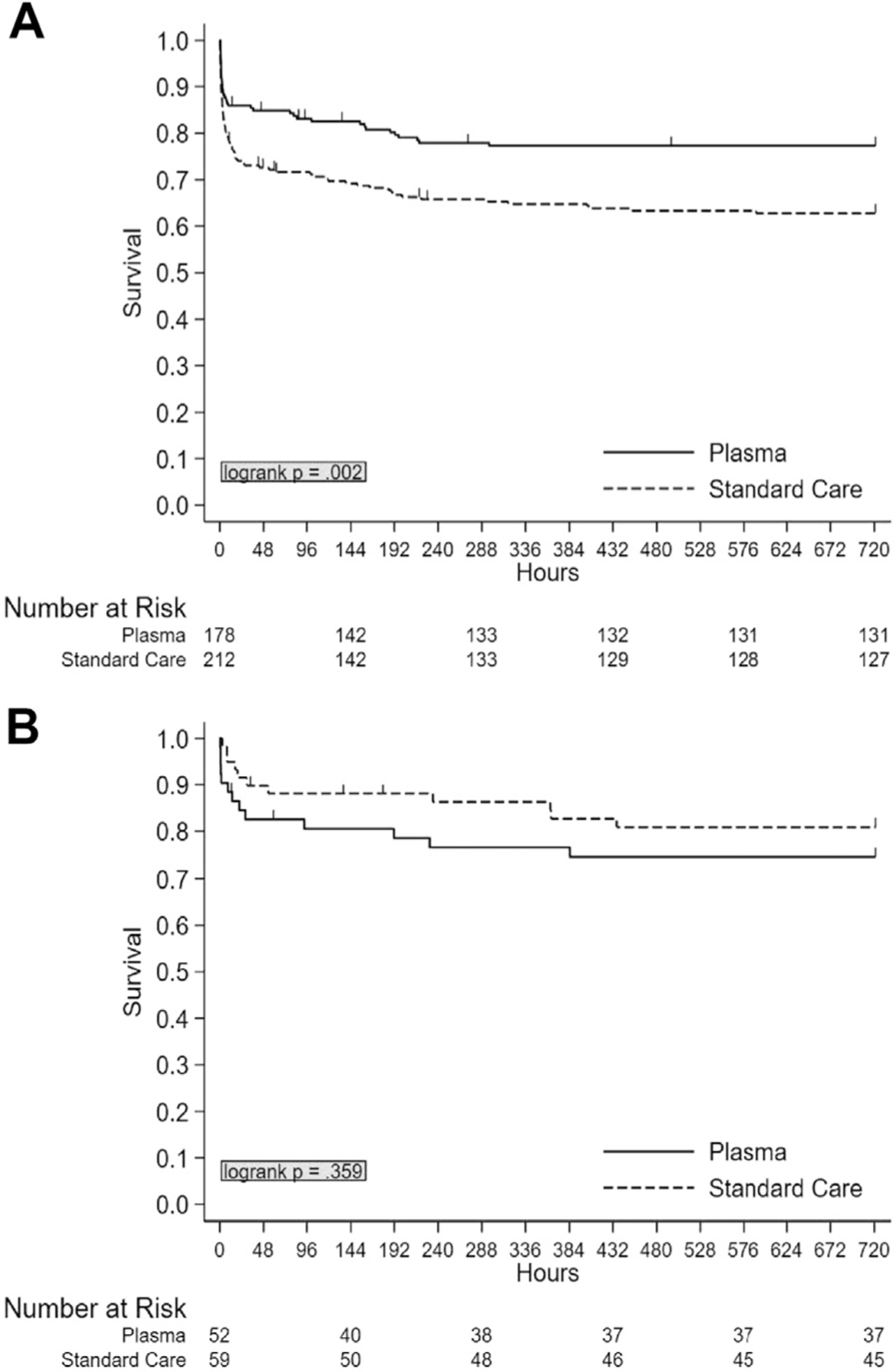

We then performed a Kaplan-Meier survival analysis for both 24-hour and 30-day mortality. The analysis revealed that there was a significant 24-hour survival benefit in SCENE group patients who received plasma compared to those who received standard of care (P = .005) but not in transfer patients (P = .37) (Fig 1). Similarly, there was a significant 30-day survival benefit in SCENE group patients who received plasma compared to those who received standard of care (P = .002) but not in transfer patients (P = .36) (Fig 2).

Figure 1.

Unadjusted Kaplan-Meier 24-hour survival analysis comparing plasma and standard care group patients stratified by air medical transfer origin. (A) SCENE versus (B) REF.

Figure 2.

Unadjusted Kaplan-Meier 30-day survival analysis comparing plasma and standard care patients stratified by air medical transfer origin. (A) SCENE versus (B) REF.

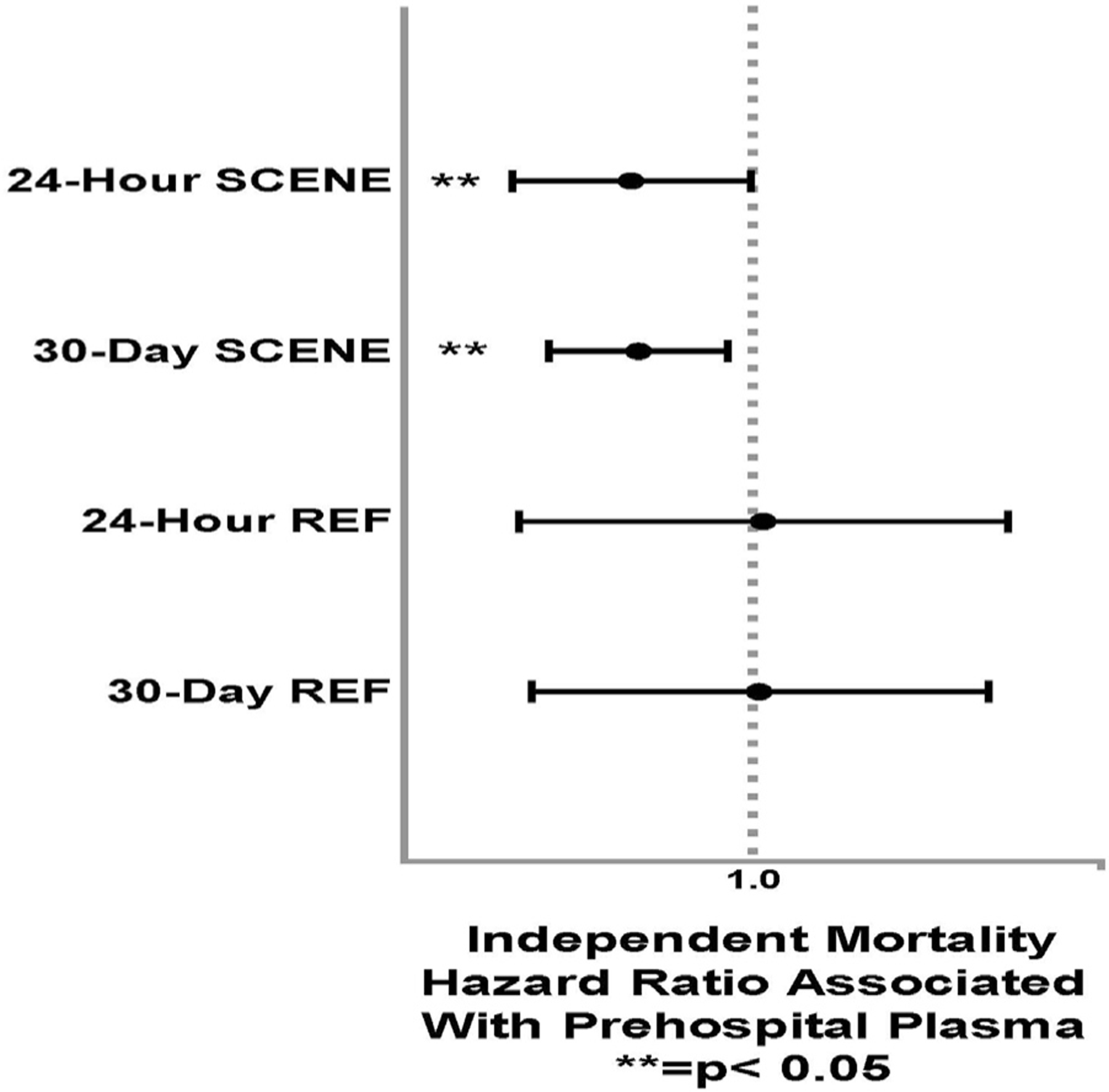

To verify our findings, multivariate analysis of survival using Cox proportional-hazard models adjusted for clinically and statistically significant covariates, including prehospital crystalloid, prehospital transport time, ISS, and initial GCS, was performed to characterize the independent effects of prehospital plasma when stratified by transfer origin (SCENE versus REF). These models demonstrated that prehospital plasma treatment was associated with a 43% reduction in risk of 24-hour mortality (HR 0.57, 95% CI 0.33–0.99, P = .047) and a 41% reduction in risk of 30-day mortality (HR 0.59, 95% CI 0.39–0.89, P = .012) in SCENE group patients. (Table IV). There was no significant mortality benefit associated with prehospital plasma found in REF group patients (24-hour HR 1.05, 95% CI 0.3–3.2, P = .93; 30-day HR 1.03, 95% CI 0.4–3.0, P = .95) using identical models and the HRs approximating 1.0 (Fig 3).

Table IV.

Multivariate Cox-hazard regression model characterizing the independent association of plasma with 24-hour and 30-day mortality in SCENE patients

| HR | P value | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24-h mortality in scene patients | ||||

| Plasma treatment | *0.57 | .047 | 0.33 | 0.99 |

| Prehospital crystalloid | 1.00 | .664 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Prehospital transport time | 1.00 | .051 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| ISS | 1.00 | .781 | 0.98 | 1.01 |

| Initial GCS | 0.83 | .000 | 0.80 | 0.86 |

| 30-d mortality in scene patients | ||||

| Plasma treatment | *0.59 | .012 | 0.39 | 0.89 |

| Prehospital crystalloid | 1.00 | .701 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Prehospital transport time | 1.00 | .968 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| ISS | 1.01 | .038 | 1.00 | 1.02 |

| Initial GCS | 0.86 | .000 | 0.84 | 0.87 |

GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; HR, hazard ratio; ISS, Injury Severity Score; SCENE, transfer origin from the scene of injury.

P < .05.

Figure 3.

Forest plot of adjusted Cox-regression mortality analyses for prehospital plasma at 24 hours and 30 days across transfer origin (SCENE versus REF).

When we similarly characterized non-mortality, intensive care resource outcomes across standard care and plasma arms stratified by transfer origin, no significant differences were found in the SCENE group patients where the plasma mortality benefit is demonstrated. There was a lower rate of early operative procedures in the first 24 hours from trauma center arrival and a trend toward lower vasopressor need in the plasma comparison group found in REF group patients (Table V). These findings suggest differences in the subgroup population and may not be a prehospital plasma-derived benefit. Finally, we compared the distribution of adjudicated cause of death across SCENE and REF group patients, with the top causes of death being hemorrhage and brain injury in both stratified groups (Table VI).

Table V.

Nonmortality outcomes across plasma and standard care patients stratified by air medical transfer origin

| SCENE |

REF |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard care N = 212 | Plasma N = 178 | P value | Standard care N = 59 | Plasma N = 52 | P value | |

| Acute respiratory distress syndrome, % | 16.5 | 22.5 | .14 | 25.4 | 15.4 | .19 |

| Multiple organ failure, % | 16.0 | 23.0 | .08 | 25.4 | 17.3 | .30 |

| Nosocomial infection, % | 17.5 | 20.8 | .40 | 20.3 | 17.3 | .68 |

| Vasopressor requirement (24 h), % | 54.2 | 51.7 | .61 | 39.0 | 23.1 | .07 |

| Urgent operative procedure (24 h), % | 60.8 | 56.7 | .41 | 64.4 | 40.4 | .01* |

REF, transfer origin from a referral emergency department; SCENE, transfer origin from the scene of injury

P < .05.

Table VI.

Distribution of adjudicated cause of death across transfer origin

| Cause of Deaths, n (%) | SCENE (n = 118) | REF (n = 24) |

|---|---|---|

| Hemorrhage | 37 (31.3) | 6 (25.0) |

| TBI | 36 (30.5) | 6 (25.0) |

| Multiple organ failure | 14 (11.8) | 4 (16.6) |

| Sepsis | 2 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Withdrawal of care | 20 (16.9) | 4 (16.6) |

| Other | 9 (7.6) | 4 (16.6) |

REF, transfer origin from a referral emergency department; SCENE, transfer origin from the scene of injury; TBI, traumatic brain injury.

Discussion

The prehospital phase of care represents an increasingly important environment for interventions in severely injured patients at risk of bleeding and hemorrhagic shock.3,5,20 Beneficial treatments during this early time period may mitigate the detrimental effects of shock and the downstream complications that continue to complicate injury.4,11 Prehospital plasma during air medical transport has been shown to significantly reduce mortality, particularly in those with longer prehospital transport times and severe injury.10,12,21,22 The current analysis suggested that not all prehospital injured patients are alike and that transfer origin is an important moderator of the survival benefit attributable to pre-hospital plasma.

It has been shown that the risk of death is significantly lower when an injured patient is evaluated and treated at a definitive level 1 trauma center relative to nontrauma center care. Differences in patients, when transferred from a referral hospital versus the scene of injury, have also previously been documented.14,23 It is known that the overall risk of mortality may differ when a patient is taken directly to definitive trauma care relative to being transferred from and outside the hospital, particularly when traumatic brain injury is involved.24,25 This may be secondary to being transferred to a definitive trauma center, which is more adept with complex injury management or possible differences in case mix and injury severity. The patients who are transferred from an outside emergency department and are enrolled in a prehospital study may be a select cohort of patients who survived long enough to be transferred with an overall lower mortality risk due to this inherent bias.13 It has been shown that prehospital plasma has its greatest survival benefit in the most severely injured patients, particularly with severe polytrauma and traumatic brain injury.4,10,11 The current findings were robust, yet there were significant differences across SCENE and REF group patients. The REF group patients received greater volumes of crystalloids and prehospital red cell transfusions and had lower overall injury severity and attributable mortality. These differences may be responsible for the disparate findings across transfer origin. The modeling performed attempted to adjust for differences in case-mix across the transfer origin subgroups, and the findings remained significant and persisted. These differences across transfer origin groups still may, in part, mitigate the beneficial effect of prehospital plasma for the REF group, or the subgroup was underpowered to demonstrate benefit. Specific treatments and management at the outside emergency department were unable to be accounted for and may play a major role in our findings. There was no attributable harm signal associated with plasma in either stratified group. The possible mechanisms underlying these disparate outcome findings of plasma survival benefit across transfer origin groups are likely multifactorial. Irrespective of the underlying mechanisms driving these survival differences, the current findings highlighted the importance of prehospital patient selection for these types of clinical trials post-injury. Whether an intervention being tested is time-sensitive may not be known before trial initiation and could moderate important clinical outcomes. It may also be important whether a trial should focus on a pragmatic injured population or whether it should focus on specific study cohorts where the applicability of the results may be limited and less broad.

The current results may have been one of the first studies to demonstrate the survival outcome differences from intervention due to transfer origin in the setting of a prehospital randomized clinical trial. It may be that the timing of plasma is important, even when the intervention is transfused in the prehospital environment. The transfer origin may also represent a proxy for the interval of time between plasma transfusion and the time of injury. The enrolled patients transferred from the SCENE group may have received prehospital plasma earlier, closer to the time of injury, relative to REF group patients, where the time interval between injury and plasma is longer. The time of enrollment was when air medical transport arrived at the scene of injury or at the outside emergency department, and the patient met vital sign criteria. The time of injury was not a reliable variable and was unable to be recorded for the trial and represents an important limitation for the current analysis and determining the possible reasons for the differences in survival found.6

There were additional limitations of the current analysis. The study was a secondary, post hoc analysis, and the randomization was not focused around, and the data was not recorded specifically to characterize transfer origin groups. The subgroup populations were small, possibly underpowered, are at risk of type II error, and should be considered exploratory. The original trial was pragmatic and used simple vital sign criteria to enroll patients. There were differences in prehospital transport time that may have been important mediators of outcomes, and differences across sites may have been relevant. Despite using a robust statistical approach, the potential for residual confounding exists, and there may have been differences across transfer origin groups that were not measured and are unable to be accounted for. Despite modeling, the differences in injury severity may have been hard to adjust for, and prehospital plasma may have its most robust effect in those at highest risk of mortality.6,10 Although the trial data was collected prospectively, the acuity of management of the enrolled injured patients and the time-sensitive laboratory measurements (eg, arrival lactate and hemoglobin indices) lead to missingness. Although missingness did not differ across transfer origin groups, missing laboratory data represented a limitation for that comparison. Finally, these outcome differences were specific to a prehospital plasma intervention. It is not known whether other blood transfusion components, such as red cells or whole blood, would demonstrate similar findings.

In conclusion, prehospital plasma is significantly associated with higher survival in trauma patients at risk for hemorrhagic shock who arrive from the scene of injury, although no significant association is demonstrated for those who are transferred from a referral emergency department. The underlying reasons for these disparate outcome findings remain obscure, but these outcome differences may be important when planning for future prehospital interventional trials, particularly when a plasma-based intervention is used. Further analyses are required to verify these findings, and the current results should be considered exploratory in nature.

Funding/Support

Supported by the US Army Medical Research and Materiel Command (W81XWH-12–2-0023 to J.L.S.).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest/Disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interests or disclosures to report.

References

- 1.Rhee P, Joseph B, Pandit V, et al. Increasing trauma deaths in the United States. Ann Surg 2014;260:13–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cannon JW. Hemorrhagic shock. N Engl J Med 2018;378:370–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li SR, Guyette F, Brown J, et al. Early prehospital tranexamic acid following injury is associated with a 30-day survival benefit: a secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg 2021;274:419–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gruen DS, Guyette FX, Brown JB, et al. Association of prehospital plasma with survival in patients with traumatic brain injury: a secondary analysis of the PAMPer cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e2016869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guyette FX, Brown JB, Zenati MS, et al. Tranexamic acid during prehospital transport in patients at risk for hemorrhage after injury: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg 2020;156:11–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sperry JL, Guyette FX, Brown JB, et al. Prehospital plasma during air medical transport in trauma patients at risk for hemorrhagic shock. N Engl J Med 2018;379:315–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shackelford SA, Del Junco DJ. Prehospital blood product transfusion and combat injury survival-reply. JAMA 2018;319:1167–1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henriksen HH, Rahbar E, Baer LA, et al. Pre-hospital transfusion of plasma in hemorrhaging trauma patients independently improves hemostatic competence and acidosis. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2016;24:145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anto VP, Guyette FX, Brown J, et al. Severity of hemorrhage and the survival benefit associated with plasma: results from a randomized prehospital plasma trial. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2020;88:141–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gruen DS, Guyette FX, Brown JB, et al. Characterization of unexpected survivors following a prehospital plasma randomized trial. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2020;89:908–914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gruen DS, Brown JB, Guyette FX, et al. Prehospital plasma is associated with distinct biomarker expression following injury. JCI Insight 2020;5:e135350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reitz KM, Moore HB, Guyette FX, et al. Prehospital plasma in injured patients is associated with survival principally in blunt injury: results from two randomized prehospital plasma trials. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2020;88:33–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu Z, Ayyagari RC, Martinez Monegro EY, et al. Blood component use and injury characteristics of acute trauma patients arriving from the scene of injury or as transfers to a large, mature US Level 1 trauma center serving a large, geographically diverse region. Transfusion 2021;61:3139–3149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.MacKenzie EJ, Rivara FP, Jurkovich GJ, et al. A national evaluation of the effect of trauma-center care on mortality. N Engl J Med 2006;354:366–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Newgard CD, McConnell KJ, Hedges JR, Mullins RJ. The benefit of higher level of care transfer of injured patients from nontertiary hospital emergency departments. J Trauma Nov. 2007;63:965–971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ho AM, Dion PW, Yeung JH, et al. Prevalence of survivor bias in observational studies on fresh frozen plasma:erythrocyte ratios in trauma requiring massive transfusion. Anesthesiology 2012;116:716–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nirula R, Maier R, Moore E, Sperry J, Gentilello L. Scoop and run to the trauma center or stay and play at the local hospital: hospital transfer’s effect on mortality. J Trauma 2010;69:595–599;discussion 599–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hill AD, Fowler RA, Nathens AB. Impact of interhospital transfer on outcomes for trauma patients: a systematic review. J Trauma 2011;71:1885–1900;discussion 1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bulger EM, May S, Kerby JD, et al. Out-of-hospital hypertonic resuscitation after traumatic hypovolemic shock: a randomized, placebo controlled trial. Ann Surg 2011;253:431–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rowell SE, Meier EN, McKnight B, et al. Effect of out-of-hospital tranexamic acid vs placebo on 6-month functional neurologic outcomes in patients with moderate or severe traumatic brain injury. JAMA 2020;324: 961–974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sim ES, Guyette FX, Brown JB, et al. Massive transfusion and the response to prehospital plasma: it is all in how you define it. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2020;89:43–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pusateri AE, Moore EE, Moore HB, et al. Association of prehospital plasma transfusion with survival in trauma patients with hemorrhagic shock when transport times are longer than 20 minutes: a post hoc analysis of the PAMPer and COMBAT clinical trials. JAMA Surg 2020;155:e195085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nathens AB, Maier RV, Brundage SI, Jurkovich GJ, Grossman DC. The effect of interfacility transfer on outcome in an urban trauma system. J Trauma 2003;55:444–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hartl R, Gerber LM, Iacono L, Ni Q, Lyons K, Ghajar J. Direct transport within an organized state trauma system reduces mortality in patients with severe traumatic brain injury. J Trauma 2006;60:1250–1256;discussion 1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haas B, Stukel TA, Gomez D, et al. The mortality benefit of direct trauma center transport in a regional trauma system: a population-based analysis. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2012;72:1510–1515;discussion 1515–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]