Contact details for recommendation for screening

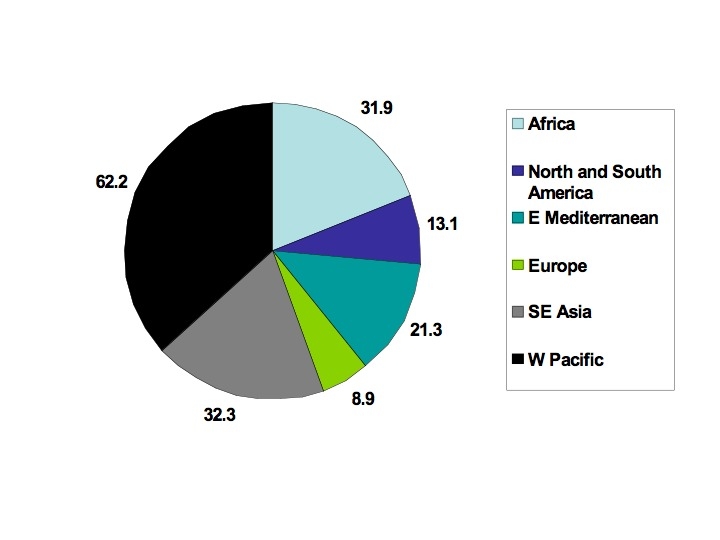

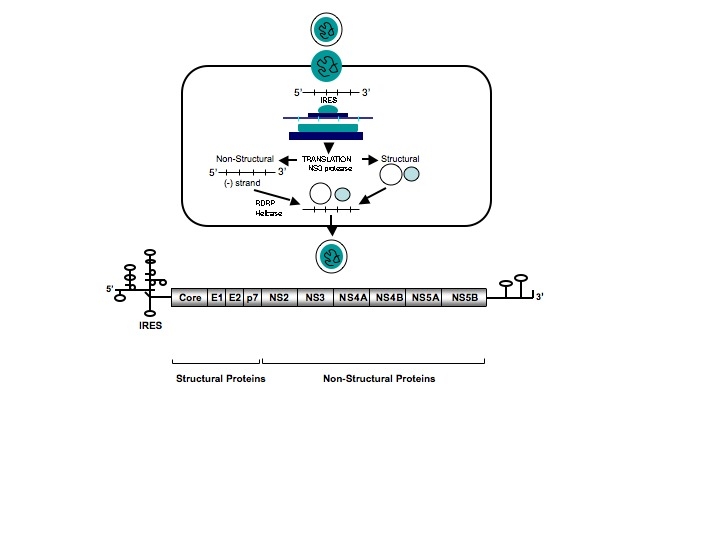

Hepatitis C virus is a single stranded RNA virus classified in the genus Hepacivirus belonging to the family Flaviviridae. The 9.6 kilobase genome encodes a polyprotein of 3000 amino acids that is processed by host cellular and viral proteinases into 10 mature structural and non-structural proteins that are essential for viral replication in the cytoplasm of hepatocytes (fig A). The World Health Organization estimates the global prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection is 3%, or 170 million patients.[1] [2] Seroprevalence is higher in Africa and Asia than in most industrialised regions, and Egypt has the highest reported seroprevalence (about 20%) because many of its residents have been exposed to the virus through parenteral antischistosomiasis therapy (fig B).[3] Phylogenetic analysis of hepatitis C virus has indicated that there are at least six major genetic groups, or genotypes, which vary by more than 30% in their nucleotide sequences, and at least 50 subtypes.[4] The geographical distribution of genotypes varies widely; genotype 1a is found commonly in North America and Europe, genotypes 2 and 3 in Western Europe and Australasia, genotype 4 in Africa and the Middle East, genotype 5 in southern Africa, and genotype 6 in South East Asia. Based on data from clinical studies, it seems that although hepatitis C virus genotypes are important in predicting response to antiviral therapy, they do not influence viral transmission, pathogenesis, or the clinical course of the disease.[5]

Fig A Overview of Hepatitis C Virus Genome and Lifecycle. The hepatitis C virus (hepatitis C virus) nucleocapsid is released into the cytoplasm following receptor mediated endocytosis, and polyprotein translation is initiated through the internal ribosome entry site (IRES) located at the 5’untranslated region of the genome. Host peptidase cleavage of the polyprotein produces structural proteins that form the nucleocapsid and protective outer layer of the virion. Posttranslational processing results in the generation of non-structural proteins that in turn encode a number of hepatitis C virus-specific enzymes (including NS3 protease, NS5B RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RDRP), and helicases) that help coordinate the intracellular life cycle of the hepatitis C virus replication complex. These viral enzymes represent potential targets for antiviral therapy. Negative-strand RNA intermediates serve as a template for polyprotein translation, following which viral particles are assembled in the endoplasmic reticulum, and mature virions are released into pericellular spaces.

Fig B Estimated global prevalence of chronic hepatitis C viral infection (in millions) based on hepatitis C virus antibody testing and a global population of 5811 million

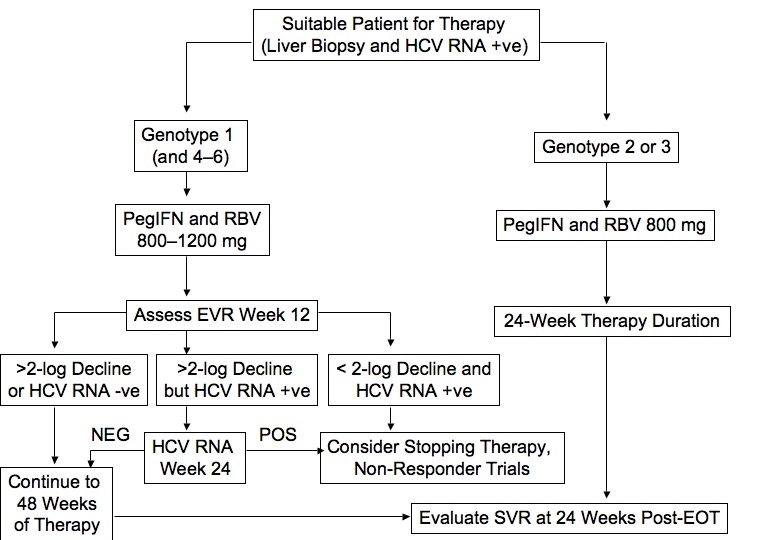

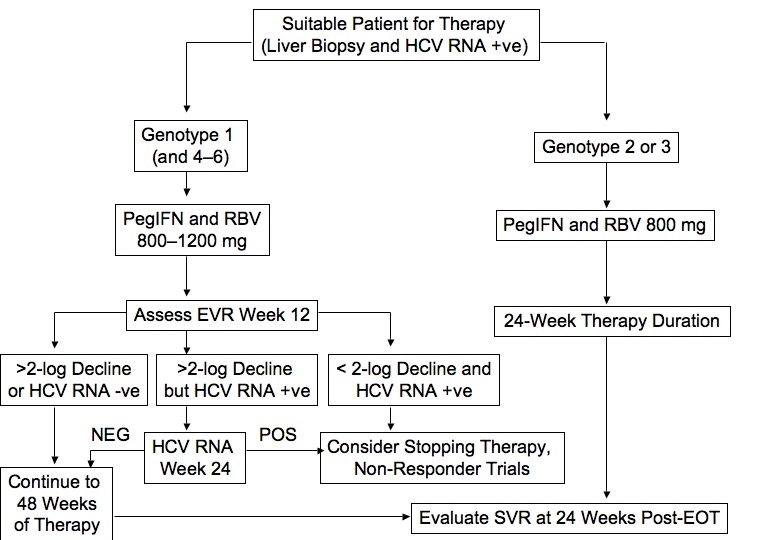

Fig C Algorithm for Initial Treatment of Chronic Hepatitis C. Although duration of treatment is generally based on genotype, some patients may require or opt for longer-term therapy depending on severity of disease on biopsy, HIV-1 co-infection, baseline hepatitis C virus RNA, and on-treatment virologic response. EOT, end of therapy; EVR, early virologic response; hepatitis C virus, hepatitis C virus; IFN, interferon; SVR, sustained virologic response.

Contact details for recommendations for screening

Centers for Disease Control,[5] US Preventative Services Task Force,[6] and National Institutes of Health.[7]

1. World Health Organization. Hepatitis C. Factsheet No 164 (updated Oct 2000). www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets (accessed 3 Feb 2006).

2. Shepard CW, Finelli L, Alter MJ. Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection. Lancet Infect Dis 2005;5:558-67.

3. Frank C, Mohamed MK, Strickland GT, Lavanchy D, Arthur RR, Magder LS, et al. The role of parenteral antischistosomal therapy in the spread of hepatitis C virus in Egypt. Lancet 2000;355:887-91.

4. Simmonds P, Bukh J, Combet C, Deleage G, Enomoto N, Feinstone S, et al. Consensus proposals for a unified system of nomenclature of hepatitis C virus genotypes. Hepatology 2005;42:962-73.

5. Seeff LB. Natural history of chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 2002;36(suppl 1):S35-46.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations for prevention and control of hepatitis C virus and HCV-related chronic disease. MMWR Recomm Rep. Oct 1998;47(RR-19):1-39. www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00055154.htm (accessed 6 Mar 2006).

7. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for hepatitis C: recommendation statement. March 2004. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. www.ahrq.gov/clinic/3rduspstf/hepcscr/hepcrs.htm (accessed 3 Mar 2006).

8. NIH Consensus Statement on Management of Hepatitis C: 2002. NIH Consens State Sci Statements 2002;19(3):1-46. http://consensus.nih.gov/2002/2002HepatitisC2002116html.htm (accessed 6 Mar 2006).

NDDIC, 2 Information Way, Bethesda, MD 20892–3570, USA. Phone: 1–800–891–5389, fax: 703–738–4929, e-mail: nddic@info.niddk.nih.gov, internet: http://digestive.niddk.nih.gov

American Liver Foundation, 75 Maiden Lane, Suite 603, New York, NY 10038, USA. Phone: 1–800–GO–LIVER (465–4837), 1–888–4HEP–USA (443–7222), or 212–668–1000, fax: 212–483–8179, e-mail: info{at}liverfoundation.org, internet: www.liverfoundation.org

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1600 Clifton Road NE, Mail Stop G37, Atlanta, GA 30333, USA. Phone: 404–371–5900, fax: 404–371–5488, internet: www.cdc.gov

Hepatitis Foundation International, 504 Blick Drive, Silver Spring, MD 20904–2901, USA. Phone: 1–800–891–0707 or 301–622–4200, e-mail: hepfi@hepfi.org, internet: www.hepfi.org

UK National Health Service. Phone: 0800 451451, internet: www.hepc.nhs.uk

British Liver Trust, Portman House, 44 High Street, Ringwood, Birmingham BH24 IAG. Phone: 0870 770 8028, e-mail:info@britishlivertrust.org.uk, internet: www.britishlivertrust.org.uk