Legname et al. 10.1073/pnas.0608970103. |

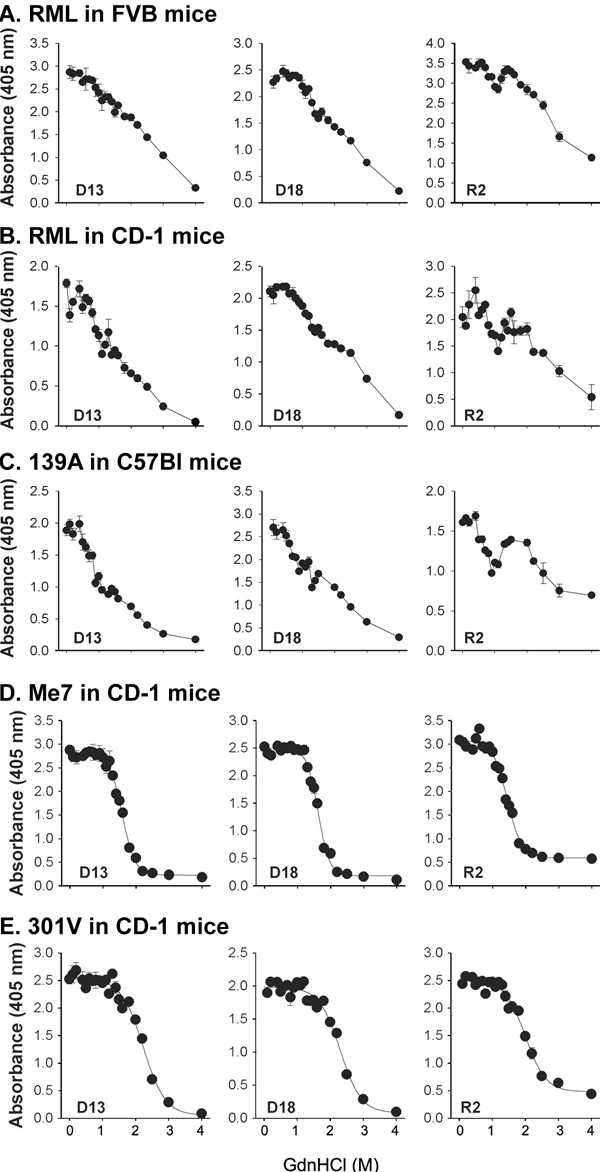

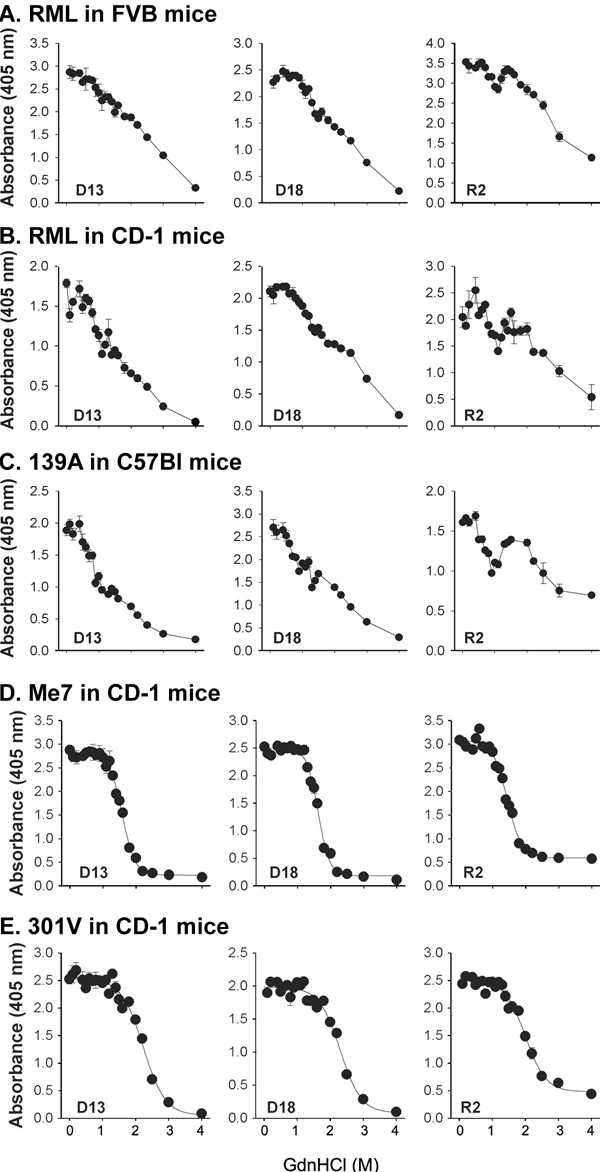

Fig. 5. Denaturation transitions of PrPSc from the RML, 139A, Me7, and 301V strains with increasing concentrations of Gdn·HCl. As described in the Supporting Text, P2 fractions were prepared from brains of FVB mice (n = 5) inoculated with RML prions (A); CD-1 mice (n = 4) inoculated with RML prions (B); C57B mice (n = 5) inoculated with 139A prions (C); CD-1 mice (n = 4) inoculated with Me7 prions (D); and CD-1 mice inoculated with 301V prions (E). Fractions were treated with increasing concentrations of Gdn·HCl (0-4 M) at 22°C. Following 1 h of incubation, the samples were diluted, treated with proteinase K for 1 h at 37°C, and precipitated with methanol/chloroform. ELISA wells were coated with 50 ml of denatured proteins. PrPSc was detected with the following Fabs: D13, D18, and R2, shown in the left, middle, and right graphs, respectively, of each image. Data points and bars represent the mean and standard deviation, respectively, of duplicate readings.

Fig. 6. Calibration of the densitometric quantification of recMoPrP(89-230) in Western blots. Aliquots of purified recMoPrP(89-230) were analyzed by SDS/PAGE and Western blotting, followed by densitometry (see Supporting Text). The graph shows the normalized densitometric signal as a function of increasing amounts of recMoPrP(89-230): 0.0156, 0.03125, 0.05, 0.0625, 0.1, 0.125, 0.185, 0.25, 0.375, 0.5, 0.75, 1, and 2 mg. The two curves were obtained by scanning a photographic film of the Western blot results (open circles) and by detecting the Western blot chemiluminescence signals directly (filled circles). For either curve, a linear relationship exists between the signal and recMoPrP(89-230) up to 0.5 mg. The slopes of the two curves differ slightly and may be due to the different methods of data acquisition. For all of the studies described in this manuscript, photographic film was used following by quantification through densitometric scanning.

Fig. 7. Gdn·HCl -meditated denaturation profiles of PrPSc in undiluted and 10-fold diluted mouse brain homogenates. These conformational-stability assays were performed on synthetic prions in the brain of a Tg9949 mouse (MK4985) on first passage and in the brain of an FVB mouse (MN9060) on second passage. (A) Western blots of PrPSc in brain extracts of the MK4985 mouse inoculated with synthetic prions on first passage. Samples were either undiluted (Left) or diluted 10-fold (Right). The [Gdn·HCl]1/2 values for synthetic prions in undiluted and diluted samples were 4.9 and 3.9 M, respectively. (B) Western blots of PrPSc in brain extracts of the MN9060 mouse inoculated with synthetic prions on second passage. Samples were either undiluted (Left) or diluted 10-fold (Right). The [Gdn·HCl]1/2 values for synthetic prions in undiluted and diluted samples were 3.8 and 3.0 M, respectively. In each lane, 10 ml of brain homogenate was loaded and immunoblotted with HuM-Fab D18. Control lane C, undigested, undenatured sample; lanes 0-6, samples were exposed to final molar concentrations of Gdn·HCl, as indicated, followed by limited PK digestion. Molecular weight markers based on the migration of protein standards are indicated in kDa.

Fig. 8. Conformational-stability assays of synthetic prions on first passage in Tg9949 mice. Western blots (A, C, E, and G) of PrPSc in brain extracts of Tg9949 mice inoculated with synthetic prions on first passage. In each lane, 10 ml of brain homogenate was loaded and immunoblotted with HuM-Fab D18. Control lane C, undigested, undenatured sample; lanes 0-6, samples were exposed to final concentrations of Gdn·HCl, as indicated, followed by limited PK digestion. Molecular weight markers based on the migration of protein standards are indicated in kDa. Denaturation curves (B, D, F, and H) were obtained by scanning the PK-resistant, PrPSc signals in Western blots for each Tg9949 brain. [Gdn·HCl]1/2 values for the synthetic prions correspond to the midpoint transitions as shown and range from 3.3 to 5.1 M.

Fig. 9. Conformational-stability assays of synthetic prions on second passage in Tg9949 mice. Brain homogenates from one Tg9949 mouse (MK4977) that died at 379 days after inoculation with synthetic prions were inoculated into three other Tg9949 mice. When these three mice died, brain homogenates were prepared and immunoblotted (A, C, and E) for PrPSc, as described in the legend to SI Fig. 8. Denaturation curves (B, D, and F) show [Gdn·HCl]1/2 values that vary from 2.4 to 4.0 M, suggesting the inoculum contains a mixture of prion strains.

Table 3. Reproducibility of conformational stability measurements of MoSP1 compared with other prion strains

Inoculum* | Recipient mouse | Mouse ID | [GdnHCl]1/2 (M ± SEM) | Incubation period (days ± SEM) | (n/n0)† | Number of repeats | Method‡ |

MoPrP(89-230) | Tg9949 | MK4985 | 4.9 ± 0.1 | 523 | 5 | WB | |

Tg9949 | MK4979 | 5.1 ± 0.1 | 522 | 6 | WB | ||

Tg9949 | MK4977 | 3.3 ± 0.3 | 379 | 1 § | WB | ||

Tg9949 | MK4974 | 5.0 ± 0.1 | 505 | 6 | WB | ||

MK4977 | Tg9949 | MM6060 | 3.7 ± 0.1 | 270 | 4 | WB | |

Tg9949 | MM6059 | 3.7 ± 0.1 | 270 | 1 § | WB | ||

Tg9949 | MM6055 | 2.9 ± 0.1 | 204 | 1 § | WB | ||

Tg9949 | MM6054 | 4.0 ± 0.1 | 327 | 1 § | WB | ||

Tg9949 | MM6050 | 2.4 ± 0.1 | 190 | 2 | WB | ||

MK4985 | FVB | MN70149 | 4.4 ± 0.1 | 453 | 2 | WB | |

MM6060 | Tg9949 | MN12916 | 3.4 ± 0.1 | 301 | 2 | WB | |

MK4977 | Tg4053 | MN11316 | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 88 | 2 | WB | |

RML | Tg4053 | MN8064 | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 60 | 4 | WB | |

RML | Tg9949 | N/A | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 161 ± 2 | 11/11 | 3 | WB |

RML | FVB | MM10872 | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 117 ± 3 | 10/10 | 4 | WB |

RML | CD-1 | N/A | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 133 ± 2 | 29/29 | 2 | E |

RML | CD-1 | N/A | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 117 ± 1 | 86/86¶ | 4 | WB |

Me7 | CD-1 | N/A | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 145 ± 2 | 24/24 | 2 | E |

301V | CD-1 | N/A | 2.2 ± 0.1 | 230 ± 3 | 10/10 | 2 | E |

139A | C57Bl6 | N/A | 2 | 147 ± 1 | 14/14 | 2 | E |

*Inocula are synthetic prions formed from recMoPrP(89-230) polymerized into amyloid; Tg9949 mouse brains MK4977, MK4985, and MM6060; and mouse RML prions.

†

n, number of animals developing clinical signs of prion disease; n0, number of animals inoculated. Animal dying atypically following inoculation were excluded (1).‡

WB, Western blot; E, ELISA.§

Brain homogenates were not available for additional experiments.¶

Mice were killed at 122 dpi and brains pooled together.1.Prusiner SB, McKinley MP(1987) Prions-Novel Infectious Pathogens Causing Scrapie and Creutzfeld-Jakob Disease (Academic, Orlando, FL), pp. 534.

Supporting Text

Introduction

Despite a wealth of data arguing that prions are composed solely of isoforms of the disease-causing prion protein, designated PrPSc, the composition of the infectious prion particle continues to be debated (1-3), largely because prions exist in many different strains. Each strain enciphers a distinct phenotype characterized by specific incubation times as well as by patterns of vacuolation and PrPSc deposition in the CNS (4-6).

PrPSc is formed from the cellular prion protein (PrPC) by a process during which PrPC undergoes a profound conformation change (7). NMR studies have shown PrPC is composed largely of three a-helices and two short b-strands (8, 9); PrPSc is likely to retain its C-terminal a-helix and a portion of a second a-helix while much of the molecule is refolded into a b-helix (10, 11). It is noteworthy that biophysical studies have been of insufficient resolution to demonstrate directly the putative b-helix.

Concerned that our synthetic prions might be laboratory contaminants despite numerous control studies (12), we studied one isolate using the conformational-stability assay (13). The exceptionally high resistance of this synthetic prion isolate to Gdn·HCl -mediated denaturation argued that the isolate is not a contaminant. Indeed, this prion isolate seems to differ from all other naturally occurring prions previously studied.

ELISA denaturation curves of natural prion strains.

Three PrP-specific rec human/mouse (HuM)-Fabs that recognize different epitopes of the PrP 27-30 molecule were used to assess the levels of PrPSc after Gdn·HCl denaturation (14). The HuM-D13 Fab (D13) binds to an epitope (residues 95-105) in the middle of PrP, HuM-D18 (D18) reacts with an epitope at residues 133-157, and R2 binds at C-terminal residues 225-231 (ref. 15). In the brains of FVB mice inoculated with RML prions, the level of MoPrP 27-30 decreased progressively as the concentration of Gdn·HCl increased up to 4 M. With the D18 and R2 recHuM-Fabs, the denaturation profiles were biphasic, raising the possibility of at least two distinct populations of PrPSc molecules with different stabilities. Similar results were found with RML prions propagated in wild-type (wt) CD-1 mice [supporting information (SI) Fig. 5B]. When the denaturation profiles for 139A prions propagated in C57Bl6 mice were plotted, the biphasic character of these profiles is even more pronounced (SI Fig. 5C). Both RML and 139A prions were derived from the Chandler isolate (16).In contrast to the denaturation profiles of RML and 139A prions (SI Fig. 5), Me7 or 301V prions propagated in CD-1 mice appear to be monophasic (SI Fig. 5 D and E). These curves suggest the population of PrPSc molecules is rather uniform with respect to their conformational stability. In contrast to Me7, where all of the PrPSc molecules were denatured by 2 M Gdn·HCl (SI Fig. 5D), 301V required 3 M; both RML and 139A prions required 4 M Gdn·HCl for complete denaturation. An alternative approach to gain comparative data is to measure the [Gdn·HCl]1/2 values. The [Gdn·HCl]1/2 values ranged from 1 to 2 M for RML and 139A; 1.6 to 1.7 M for Me7; and 2.2 to 2.4 M for 301V.

Linearity of the denaturation profiles.

In the studies that used Western blots, we determined the range over which a linear response to Gdn·HCl -mediated denaturation could be expected. The densitometric scanning of the unglycosylated PrP band in Western blots was used to quantify the level of PrPSc after exposure to a specified concentration of Gdn·HCl followed by limited digestion with proteinase K (PK). First, we calibrated the system using MoPrP(89-230). The response was linear over a 30-fold range of PrP levels from 0.016 to 0.5 mg of purified recMoPrP(89-230) when the blots were exposed to photographic film and then scanned (SI Fig. 6). All of the Western blots had signals that were in the linear response range of the calibration curve. Although unneeded, the linear response range could be extended over 60-fold to ~1 mg of purified recMoPrP(89-230) when the chemiluminescence of gels was measured directly.Second, we diluted selected brain homogenates by a factor of 10 or 100 as a second method to ensure the linearity of the Gdn·HCl response. When samples were diluted 10-fold, they exhibited slightly modified Gdn·HCl -mediated denaturation profiles compared to the undiluted samples. Only those samples with high intensity signals could be evaluated after a 10-fold dilution of the brain homogenate (see SI Figs. 8 and 9). As shown, conformational-stability assays were performed on synthetic prions in the brain of a Tg9949 mouse (MK4985) on first passage and in the brain of an FVB mouse (MN9060) on second passage. The Western blots of the undiluted and 10-fold diluted homogenate of the MK4985 brain (SI Fig. 7A) are similar but the [Gdn·HCl]1/2 values for the synthetic prions of undiluted and 10-fold diluted samples differ; they are 4.9 M and 3.9 M, respectively. Like the Western blots in SI Fig. 7A, the blot of the undiluted and 10-fold diluted homogenate of the MN9060 brain (SI Fig. 7B) are similar while the [Gdn·HCl]1/2 values for the synthetic prions of undiluted and 10-fold diluted samples differ somewhat less; they are 3.8 M and 3.0 M, respectively. Although the Gdn·HCl values were reduced as much as 20% upon 10-fold dilution of the brain homogenate, the shape of the denaturation curves was unchanged. No signals were observed under the conditions of the experiment when these samples were diluted by a factor of 100.

While the change in [Gdn·HCl]1/2 values was readily measurable after a 10-fold dilution of some of the samples, not all 30 samples had sufficiently high PrPSc levels to permit analysis after a 10-fold dilution (Fig. 4). As a compromise, all of the [Gdn·HCl]1/2 values used in the plot of [Gdn·HCl]1/2 values versus incubation times were from studies using undiluted brain homogenates (Fig. 4).

Reproducibility of denaturation experiments using Western blots and ELISA protocols.

Denaturation experiments were performed using two different techniques: ELISA and Western blots. The results obtained with the former have been discussed above. The results obtained with the latter have been discussed in the main text. It is important to note that the studies performed with the ELISA used pooled brains from several mice to obtain the denaturation curves. Typically, six mouse brains were homogenized followed by centrifugation to produce the P2 fraction (see Supporting Materials and Methods below). SI Table 3 lists the number of replicas obtained for each sample analyzed. Each experiment performed using ELISA denaturation was carried out in duplicate for each strain reported. Therefore, the [Gdn·HCl]1/2 values determined by ELISA should be considered mean values for the particular strain analyzed.Using the Western blot protocol to determine the conformational stability of synthetic and naturally occurring prions, either several individual experiments were performed on tissue samples of a single brain (see number of experiments in SI Table 3) or on pools of brains as in the case of RML-inoculated, CD-1 mice where four independent experiments were performed. For the synthetic prion samples from MK4985 and MK4979 mice, the [Gdn·HCl]1/2 values were determined 5 and 6 times, respectively; these values ranged between 4.9 and 5.1 M. Statistical analyses of the denaturation curves gave low standard error intervals.

Energy landscape and calculation of D G0.

If we assume that each prion isolate exhibits a slightly different tertiary structure and each tertiary structure specifies a particular quaternary structure, we are presented with a conundrum. We must ask, how many different tertiary structures can a protein adopt? What is the energy landscape of a protein with so many structures? We have no biophysical precedent for such a macromolecule.The mechanism by which Gdn·HCl denatures PrPSc and renders it sensitive to limited proteolysis is unknown. Whether Gdn·HCl renders PrPSc susceptible to proteolytic digestion by disrupting tertiary or quaternary structure (or both) remains to be established. It will be important to establish whether large aggregates of PrPSc are more resistant to Gdn·HCl denaturation than small ones. If so, then prion isolates causing disease in 500 days ought to be more aggregated than those causing disease in 60 days. Can we convert a 500-day isolate into a 60-day isolate by sonication or some other procedure that disperses large aggregates of PrPSc?

Based on conformational-stability measurements, we set out to calculate D G0 values for each prion isolate from SI Figs. 8 and 9. Many parameters were considered in analyzing the thermodynamic stability of synthetic prions. The temperature dependence of protein unfolding is of inherent thermodynamic importance. All conformational-stability assays presented here were performed at 22°C. It will be of interest to perform conformational-stability measurements at different temperatures. Whether the same relationships will be maintained between prion stability and incubation time is uncertain. Preliminary calculations suggest different D G0water values exist for each prion isolate (data not shown). Such calculations are complicated by at least four different processes: (i) unfolding of PrPSc, (ii) dissociation of infectious monomers that are probably composed of PrPSc trimers (11), (iii) dissociation of multimers of infectious monomers, and (iv) refolding of partially denatured PrPSc. The specific contributions of each of these four processes to the melting of PrPSc by exposure to increasing concentrations of Gdn·HCl remain to be defined. While measuring the conformational stability of PrPSc by limited proteolysis is crude procedure, the ability to perform this procedure on homogenates permits measurements using a small portion of a single mouse brain. Since PrPSc represents <0.01% of the protein in an RML-infected mouse brain, studies on purified samples of PrPSc present a considerable challenge (17).

Material and Methods

Prion strains.

Transmission of BSE prions from dairy cattle to VM mice generated the 301V strain (18). Scrapie prions from Suffolk sheep propagated in C57BL mice led to the Me7 strain (19). These strains were passaged in Swiss CD-1 and FVB mice obtained from Charles River Laboratories. The full-length murine RML prion strain propagated in Swiss mice was initially provided by W. Hadlow (Rocky Mountain Laboratory, Hamilton, MT) and was passaged in Swiss CD-1 and FVB mice obtained from Charles River Laboratories (16). Synthetic prions were produced as previously described (12).Preparation of brain homogenates.

Crude brain homogenates (10% (wt/vol)) in calcium- and magnesium-free PBS were prepared by repeated extrusion through syringe needles of successively smaller size, as previously described (20). The brain homogenates prepared from killed, diseased mice were used for serial passage as well as characterization of PrPSc.HuM-Fab preparation.

Mouse Fabs obtained from a phage display library (21) was used in the construction of the HuM-D13, HuM-D18 and HuM-R2 clones. Preparation of HuM-Fabs was performed as described previously (22).PrPSc detection by Western immunoblotting.

PrPSc was measured by limited PK digestion and immunoblotting as described previously (23). Limited protease digestion was performed with 20 mg/ml PK (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) for 60 min at 37°C. Digestions were terminated by the addition of 10 ml of 100 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) in absolute methanol (Roche). Digested samples were then mixed with equal volumes of 2 ´ SDS sample buffer. All samples were boiled for 10 min before electrophoresis. SDS-PAGE analyses were performed on 1.5-mm, 13% polyacrylamide gels (24). Following electrophoresis, Western blotting was performed as previously described (20). Membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat milk protein in TBST (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8; 150 mM NaCl plus 0.05% Tween-20) for 1 h at room temperature. Blocked membranes were incubated with 1 mg/ml recombinant HuM-D18. Following incubation with the primary Fab, membranes were washed 3 ´ 10 min in TBST, incubated with horseradish peroxidase-labeled, anti-human Fab secondary antibody (ICN) diluted 1:5000 in TBST for 45 min at room temperature, and washed again, 4 ´ 10 min in TBST. After enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) detection (Amersham Pharmacia Bioscience, Piscataway, NJ) for 1 to 5 min, blots were sealed in plastic covers and exposed to ECL Hypermax film (Amersham Pharmacia). Films were processed automatically in a Konica film processor.1. Chesebro B (2004) Science 305:1918-1921.

2. Nishida N, Katamine S, Manuelidis L (2005) Science 310:493-496.

3. Jeffrey M, Gonzalez L, Espenes A, Press C, Martin S, Chaplin M, Davis L, Landsverk T, Macaldowie C, Eaton S, McGovern G (2006) J Pathol 209:4-14.

4. Dickinson AG, Meikle VMH, Fraser H (1968) J Comp Pathol 78:293-299.

5. Bruce ME, McBride PA, Farquhar CF (1989) Neurosci Lett 102:1-6.

6. Hecker R, Stahl N, Baldwin M, Hall S, McKinley MP, Prusiner SB (1990) VIIIth Intl Congr Virol, Berlin Aug 26-31 284.

7. Pan K-M, Baldwin M, Nguyen J, Gasset M, Serban A, Groth D, Mehlhorn I, Huang Z, Fletterick RJ, Cohen FE, Prusiner SB (1993) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90:10962-10966.

8. Riek R, Hornemann S, Wider G, Billeter M, Glockshuber R, Wüthrich K (1996) Nature 382:180-182.

9. James TL, Liu H, Ulyanov NB, Farr-Jones S, Zhang H, Donne DG, Kaneko K, Groth D, Mehlhorn I, Prusiner SB, Cohen FE (1997) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94:10086-10091.

10. Wille H, Michelitsch MD, Guénebaut V, Supattapone S, Serban A, Cohen FE, Agard DA, Prusiner SB (2002) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99:3563-3568.

11. Govaerts C, Wille H, Prusiner SB, Cohen FE (2004) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:8342-8347.

12. Legname G, Baskakov IV, Nguyen H-OB, Riesner D, Cohen FE, DeArmond SJ, Prusiner SB (2004) Science 305:673-676.

13. Legname G, Nguyen H-OB, Baskakov IV, Cohen FE, DeArmond SJ, Prusiner SB (2005) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:2168-2173.

14. Peretz D, Scott M, Groth D, Williamson A, Burton D, Cohen FE, Prusiner SB (2001) Protein Sci 10:854-863.

15. Peretz D, Williamson RA, Matsunaga Y, Serban H, Pinilla C, Bastidas RB, Rozenshteyn R, James TL, Houghten RA, Cohen FE, Prusiner SB, Burton DR (1997) J Mol Biol 273:614-622.

16. Chandler RL (1961) Lancet 1:1378-1379.

17. Prusiner SB, McKinley MP, Bowman KA, Bolton DC, Bendheim PE, Groth DF, Glenner GG (1983) Cell 35:349-358.

18. Fraser H, Bruce ME, Chree A, McConnell I, Wells GAH (1992) J Gen Virol 73:1891-1897.

19. Dickinson AG, Meikle VM (1969) Genet Res 13:213-225.

20. Scott M, Foster D, Mirenda C, Serban D, Coufal F, Wälchli M, Torchia M, Groth D, Carlson G, DeArmond SJ, Westaway D, Prusiner SB (1989) Cell 59:847-857.

21. Williamson RA, Peretz D, Pinilla C, Ball H, Bastidas RB, Rozenshteyn R, Houghten RA, Prusiner SB, Burton DR (1998) J Virol 72:9413-9418.

22. Peretz D, Williamson RA, Kaneko K, Vergara J, Leclerc E, Schmitt-Ulms G, Mehlhorn IR, Legname G, Wormald MR, Rudd PM, Dwek RA, Burton DR, Prusiner SB (2001) Nature 412:739-743.

23. Supattapone S, Nguyen H-OB, Cohen FE, Prusiner SB, Scott MR (1999) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96:14529-14534.

24. Laemmli UK (1970) Nature 227:680-685.

25. Prusiner SB, McKinley MP (1987) (Academic, Orlando,FL), p. 534.