Lee et al. 10.1073/pnas.0609763104. |

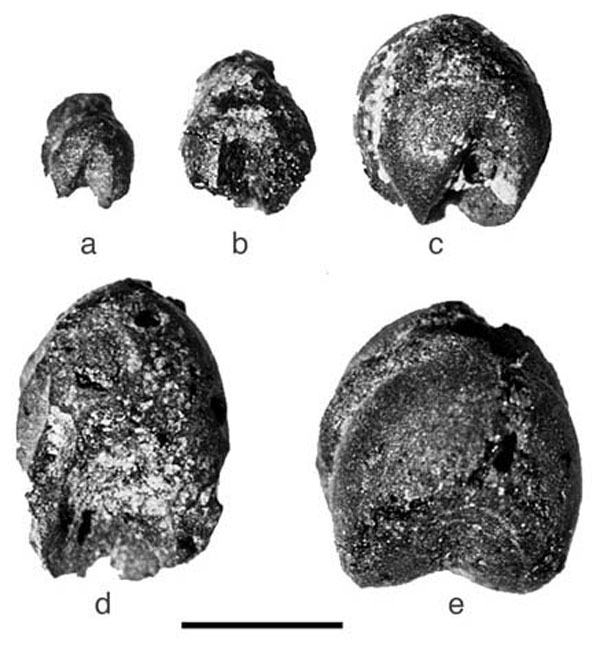

Fig. 7. Millet. (a-c) Foxtail millet from the Peiligang Wuluo Xipo (b), Erlitou Shaochai (a and c). (d and e) Broomcorn millet from the Late Yanghsao Nanwanyao (d) and Early Longshan Sigou SE sites (e). (Scale bar, 1 mm.)

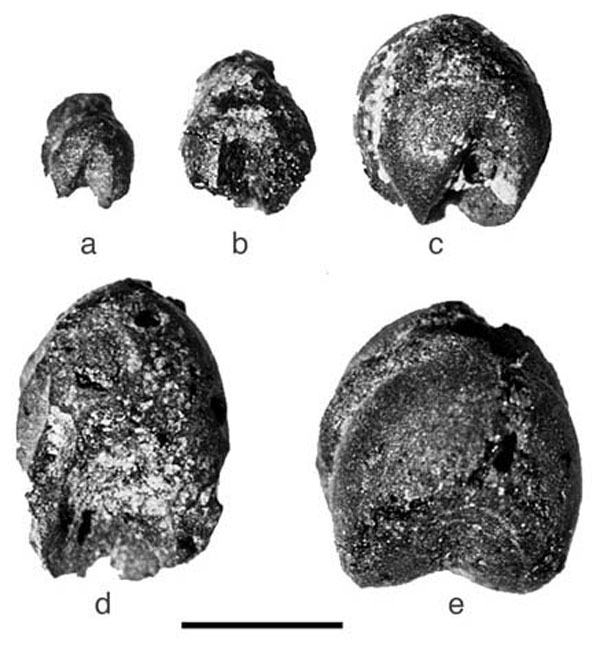

Fig. 8. Rice from the Erlitou Huizui site. (Scale bar, 1 mm.)

Fig. 9. Box plots (output from JMP statistical software; SAS Institute, Cary, NC) of length and width of complete rice grains from the Huizui site compared with rice from the Longshan period Liangchengzhen and the Early Neolithic Yuezhuang site. Blue lines indicate SD. There is considerable overlap among the measurements of the three collections, although the means appear to differ. The Huizui and Yuezhuang samples are too small to make a statistically significant comparison of means.

Fig. 10. Wheat from the Erligang Tianposhuiku site. (Scale bar, 1 mm.)

Fig. 11. Box plots (output from JMP statistical software; SAS Institute, Cary, NC) of length and width of complete wheat grains from the Tianposhuiku site and from Japan (Satsumon culture). Blue lines indicate SD. The comparison circles show that the Tianposhuiku wheat grains are statistically identical in size to the wheat grains from Japan. Both are extremely small and appear to be neither Triticum aestivum subsp. compactum nor T. aestivum subsp. sphearococcum, both of which have small grains.

Fig. 12. Soybean from the Erligang Tianposhuiku (Upper). Wild legumes: Late Longshan Matun (Lower Left) and Erligang (Lower Center) are probably either Melilotus or Lespedeza, whereas the Tianposhuiku specimen (Lower Right) is Korean clover. R, radicle; H, hilum. (Scale bar, 1 mm.)

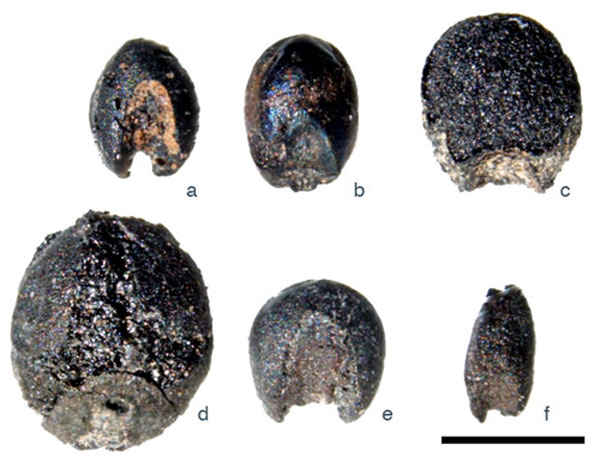

Fig. 13. Grass seeds. Green foxtail grass (a) from the Peiligang Wuluo Xipo site, panic grass (b) from the Erligang Tianposhuiku sites, other type of panic grass (c) from the Erlitou Shaochai site, and various other types from the Late Longshan Matun (d), Erlitou Huizui (e), and Tianposhuiku (f) sites. (Scale bar, 1 mm.)

Fig. 14. Seed density by period and site size.

Fig. 15. Beefsteak plant seeds from the Erligang period Tianposhuiku site. (Scale bar, 1 mm.)

Fig. 16. Pit visible in the loess cut in the Huizui site (terrace 1, pit 3). The Arrow indicates the concentration of ash and charred materials.

Seed category | Family | Common name | Scientific nomenclature |

Nut | Fagaceae | Oak | Quercus sp. |

Crops | Poaceae | Broomcorn millet | Panicum miliaceum |

|

| Foxtail millet | Setaria italica supsp. italica |

|

| Rice | Oryza sativa |

|

| Bread wheat | Triticum aestivum |

Possible crops | Fabaceae | Soybean | Glycine sp. (G. max?) |

| Lamiaceae | Beefsteak plant | Perilla frutescens |

Weeds | Poaceae | Green foxtail (green bristle grass) | Setaria italica subsp. viridis |

|

| Panic or mannagrass | Panicum sp. or Glyceria sp. |

|

| Millet tribe | Paniceae |

| Cyperaceae | Fimbry | Fimbristylis sp. |

|

| Other sedge | Carex or Cyperus sp.? |

| Brassicaceae | Mustard | Brassica sp.? |

| Chenopodiaceae | Chenopod | Chenopodium sp. |

| Polygonaceae | Knotweed | Polygonum sp. |

| Eurphorbiaceae | Spurge | Euphorbia sp. |

| Fabaceae | Korean clover | Kummerowia stipulacea |

|

| Lespedeza or sweet clover? | Lespedeza sp. or Melilotus sp.? |

| Boraginaceae | Borage family |

|

| Lamiaceae | Minature beefsteak plant | Molsa sp. |

| Solanaceae | Nightshade | Solanum sp. |

Fleshy fruits | Rosaceae | Bramble | Rubus sp. |

|

| Plum | Prunus sp. |

SI Text

Flotation and Analysis Methods.

Two flotation methods were used to process sediment samples: a manual decanting method in 1998-2001 and a modified Shell Mound Archaeology Project (SMAP)-style apparatus in 2002. Light fractions were collected with a 0.2-mm sieve. Heavy fractions were recovered in a 1-mm mesh. In the laboratory, plant remains >2 mm in their smallest dimension are sorted thoroughly into their constituent components of charred seeds and nutshell, charcoal, modern plant material such as rootlets, and mineral particles, and their weights are recorded. Only seeds and identifiable plant parts are extracted from the fractions <2 mm. Except for eight samples, only light fractions have been examined. The eight heavy fractions contained no plant remains, so none of the remaining heavy fractions was examined. Identifiable plant taxa are classified into three groups: crops, weeds, and fleshy fruits.Settlement and Technology in the Huanghe Drainage Basin.

Most Peiligang occupations are described as being substantial settlements having fully developed agricultural systems. Our working hypothesis is that the small Peiligang sites in the Yiluo valley are dry-season occupations. The late Peiligang appears to coincide with the early Hypsithermal. Geoarchaeological data point to an increase in landscape instability (riverine incising, erosion) at the time (1). How landscape instability relates to early agriculture here needs to be explored. The earliest painted pottery appears during the Early Neolithic and is from the Laoguantai occupation of the Baijia site (2). By the Yangshao period, the Hypsithermal was well established (3, 4). The landscape had stabilized, and local river floodplains were actively alluviating in the Yiluo region (1). Annual silt renewal provided fertile agricultural soil. Middle Neolithic Yangshao technology includes painted pottery as well as more utilitarian, cord-marked/stamped pottery, pottery kilns, and a diverse stone technology. Several house types (oval, rectangular, communal) are reported, and a deep ditch surrounds many sites, such as Banpo.River alluviation appears to have ceased in the Late Neolithic, and landscape instability reappeared for the first time since the early Hypsithermal (5). Late Neolithic characteristics include a four-tiered settlement system and possible urban centers. One such center, Liangchengzhen, is the current focus of an intensive archaeological study including paleoethnobotany (6). Several new material cultural traits with connections to the Shandong Peninsula's Dawenkou culture that was partly contemporary with the Henan-Shaanxi early Longshan (c. 4100-2600 B.C.) appeared in the region for the first time during the early Longshan, indicating a population influx from the east (7, 8). Eggshell thin pottery and typical Dawenkou prestige vessels are the main items that appeared. Our research includes the Longshan in the Ying River valley and the Shangqiu areas of Henan. Both studies also include later periods, and flotation samples have also been taken at one Yangshao site near Shangqiu. These projects are in progress, so we do not include those results here.

A palace complex (7.5 ha) stood in the center of the Erlitou site. A few dozen rammed-earth foundations ranging in size from 600 m2 to 10,000 m2 have been found. Members of the elite lineage enjoyed elaborate mortuary treatment, their burials often containing bronze, jade, and white pottery made of kaolin (9). Production of special bronze, bone, and pottery items was concentrated at Erlitou (1). The Yiluo region is traditionally thought to have been the location of the earliest dynasties in China (Xia, ca. 2100-1600 B.C. and Early Shang, ca. 1600-1450 B.C.). Many archaeologists believe that Erlitou represents the Xia (e.g., ref. 10). These views, however, are by no means universally held. Some argue that Erlitou represent a chiefdom and not necessarily a state (see the discussion in 11).

Cultigens.

The Late Neolithic millet grains are phenotypically similar to domesticated grains reported from late contexts elsewhere in Asia such as northeastern Japan (12, 13). A sample of 14 rice grains from the excavation phase of the project at the Huizui site averages 4.8 mm long by 2.4 mm (SI Fig. 11); none of the rice remains from the survey are complete enough to measure). For reasons we do not understand, the length varies more than the thickness. The size of the Huizui rice is consistent with that of nearly all of the charred rice reported from North China, South Korea, and Japan (6, 14). For example, the rice grains from Jiahu, in southern Henan, range from 2.5-5 mm to 0.7-2.1 mm (15). This type of rice was likely a common land race, but it would be premature to identify it as Oryza sativa subsp. japonica based on morphology alone. This small rice type appears to have been dispersed widely across northern Asia by late Longshan times. Reports of larger rice grains suggest greater variation than the Yiluo samples indicate. Rice grains from the Bronze-Age Daizui site in Liaoning Peninsula (2000-1100 B.C.) are unusually long, averaging 6.9 ´ 2.3 mm (16).The wheat grains are quite small, consistent with those recovered from contexts before A.D. 1500 in East Asia (14).

Weedy Plant Taxa.

Panicum is an extremely variable genus. The morphology of some members of the genus is similar to mannagrass (Glyceria sp.). Our samples contain a large number of specimens that we can only classify as a Panicum--Glyceria type. These seeds are in samples as old as the Late Yangshao and increase in frequency through time (Table 1). If they are mannagrass, it is important to consider that the genus is common in wetlands and rice paddy fields today (17). Considering the presence of rice phytoliths from the Yangshao period, these weeds might have been associated with paddy fields. However, without extensive comparison with modern specimens, we cannot conclude that mannagrass is in our samples. Other grass specimens cannot be classified to particular genera.1. Liu L, Chen X, Lee YK, Wright H, Rosen A (2002) J Field Archaeol 29:75-100.

2. Underhill AP (1997) J World Prehistory 11:103-160.

3. Shi Y, Kong Z, Wang S, Tang L, Wang F, Yao T, Zhao X, Zhang P, Shi S (1993) Global Planet Change 7:219-233.

4. Zhou W, Yu X, Jull T, Burr GS, Xiao JY, Lu X, Xian F (2004) Quat Res 62:39-48.

5. Liu L (2004) The Chinese Neolithic: Trajectories to Early States (Cambridge Univ Press, Cambridge, UK).

6. Crawford GW, Underhill AP, Zhao J, Lee G-A, Feinman G, Nicholas L, Luan F, Yu H, Fang H, Cai F (2005) Curr Anthropol 46:309-317.

7. Liu L (1996) Early China 21:1-46.

8. Underhill AP (2000) J East Asian Archaeol 2:93-128.

9. Erlitou Archaeological Team, Institute of Archaeology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (2004) Kaogu 5:18-37.

10. Lee YK (2002) Asian Perspect 41:15-42.

11. Liu L, Chen X (2001) Rev Archaeol 22:4-21.

12. Crawford GW (1992) in The Origins of Agriculture: An International Perspective, eds Cowan CW, Watson PJ (Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, DC), pp 7-38.

13. McGovern PE, Underhill AP, Fang H, Luan F, Hall GR, Yu H, Wang CS, Cai F, Zhao Z, Feinman GM (2005) Asian Perspect 44:249-275.

14. Crawford GW (2006) in Archaeology of Asia, ed Stark MT (Blackwell Publishing, Malden, MA), pp 77-95.

15. Chen B, Wang X, Zhang J (1999) in Wuyang Jizhu, ed Henan Institute of Archaeology (Science Press, Beijing).

16. Zhang M (2000) in Dazuizi, ed Dalian Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology (Dalian Press, Dalian, China), pp 280-284.

17. Ryang HS, Kim DS, Park SH (2004) Weeds of Korea, Morphology, Physiology, Ecology: Choripetalae (Rijeon Agricultural Resources Publications, Seoul).