Abstract

The emergence of new genes throughout evolution requires rewiring and extension of regulatory networks. However, the molecular details of how the transcriptional regulation of new gene copies evolves remain largely unexplored. Here, we show how duplication of a transcription factor gene allowed the emergence of two independent regulatory circuits. Interestingly, the ancestral transcription factor was promiscuous and could bind different motifs in its target promoters. After duplication, one paralog evolved increased binding specificity so that it only binds one type of motif, whereas the other copy evolved a decreased activity so that it only activates promoters that contain multiple binding sites. Interestingly, only a few mutations in both the DNA binding domains and in the promoter binding sites were required to gradually disentangle the two networks. These results reveal how duplication of a promiscuous transcription factor followed by concerted cis and trans mutations allows expansion of a regulatory network.

Introduction

Gene duplication is believed to be an important driver of evolution because duplicated genes often diverge and evolve new functions 1-10. Such gene duplication events occur relatively frequently, with at least 50% of prokaryotic genes and over 90% of eukaryotic genes estimated to have emerged by gene duplication 11-14.

The emergence of new genes with novel functions might require reprogramming and/or extension of the regulatory network to ensure that the new paralogs are properly expressed 9,12,15-17. Specifically, differential regulation of newly duplicated genes may be important to avoid “paralog interference”, a situation where the duplicates interfere with each other’s function 17. Gu and coworkers suggested a model of asymmetrical regulatory evolution of paralog genes after the duplication, where the regulation of one gene copy evolves rapidly, while the other copy retains the ancestral expression profile 15. In keeping with this theory, several global genome-wide studies confirm that paralogs are often differentially expressed and show an increased rate of expression divergence. This likely reflects the need for cells to evolve specific regulatory programs for the ancestral and novel gene functions that emerge after the duplication event 8,12,15,16,18-22.

While the number of studies demonstrating divergent transcriptional regulation of paralogs is increasing, few studies have investigated the molecular details underlying regulatory divergence. Some authors emphasize the importance of loss and gain of cis-regulatory elements in the evolution of paralog regulation 19,22-26. It has been demonstrated that whereas the number of cis-regulatory elements shared between two paralogs drops with their age, the total number of regulatory elements in their promoters remains the same, implying that a loss of regulatory motifs is compensated by gain of novel regulatory motifs 23. Similarly, Ihmels and coauthors reported a large-scale loss of a specific cis-regulatory element from the promoters of dozens of genes following the whole-genome duplication in the yeast lineage 22. This event led to a major transcription network reprogramming and allowed optimization of anaerobic growth in S. cerevisiae.

Apart from the importance of cis changes in the promoters of duplicated genes, changes in trans-acting factors (i.e. transcription factors that regulate the paralogs) may also play a crucial role in the evolution of paralog gene regulation. It has been shown that only 2-3% of the divergence in paralog expression is explained by changes in cis-regulatory motifs 27. Several studies further suggested that duplication of transcription factors may be an important mechanism that allows re-wiring of existing regulatory networks or the development of new regulatory circuits 12,17,28,29.

Babu and Teichmann proposed three basic scenarios of gene regulation after duplication that contemplate changes in both cis and trans regulatory elements 12. In the first scenario, both copies of the gene can stay under regulation of the same transcription factor, which is an expected outcome if the paralogs do not develop different functions, but are conserved because of dosage effects 7,11,30. Alternatively, a newly duplicated paralog can become a part of another (existing) regulatory network, for example after gaining a novel cis-regulatory element (i.e. a transcription factor binding site that did not occur in the promoter of the ancestral gene). However, some cases of neofunctionalization, where one of the paralogs acquires a completely new function, may require a completely novel regulatory circuit. A third scenario therefore involves the generation of a new regulatory cascade by duplication and functional divergence of an existing transcription factor, so that each of the two paralog target genes becomes regulated by one of the two newly duplicated transcription factors. However, the concerted duplication and evolution of a target and its transcription factor seems unlikely and intuitively requires a large number of concerted evolutionary events; except perhaps following a whole–genome duplication event2,31-35.

To investigate these scenarios, we focus on the regulation of the MAL genes in yeast. The MAL genes comprise three gene subfamilies (MALT, MALS and MALR) that allow uptake and metabolism of various disaccharides, with each subfamily showing multiple duplication and neofunctionalization events 36. The MALT subfamily encodes transporter proteins that allow active import of the sugars. Once inside the cell, the disaccharides are hydrolyzed by the MalS glycosidases. Some of the intracellular disaccharides are believed to bind the MalR regulator proteins, and these complexes activate the expression of the MALS and MALT genes 37.

We have previously shown that the MALS genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae underwent several duplication events, with some of the paralogs gaining a novel hydrolyzing activity towards α 1-6 glycosidic bonds (found for example in isomaltose and palatinose), while other MalS paralogs retained the ancestral preference for α 1-4 glycosidic bonds (for example in maltose) 7,36. Similarly, the MalT transporters also underwent duplication and functional divergence, with some of today’s paralogs importing α 1-6 substrates, while others maintained the ancestral selectivity for α 1-4 glycosides 36.

Here, we investigated how the regulation of the MALT and MALS genes evolved after their duplication and functional divergence. We show that the present-day S. cerevisiae MAL genes are regulated specifically; that is, the palatinose-specific genes are activated only in response to palatinose-like sugars, whereas the maltose-specific paralogs are only activated by maltose-like sugars. We demonstrate that this specific regulation of the two paralog groups became possible because the ancestral transcription factor MalR that regulated the ancestral MALS and MALT genes also underwent duplication. One new MalR paralog activates the expression of novel MALS and MALT responsible for palatinose utilization, while the other MalR paralog activates maltose-specific target genes. Furthermore, we establish a mutational path that explains how the differential regulation of both classes of paralog target genes could have evolved without suffering from paralog interference. Together, our results provide a detailed molecular view of how gene duplication can result in the emergence of a new transcriptional network.

Results

The MAL regulatory network allows specific regulation

The genome of the laboratory strain S. cerevisiae KV5000 harbors two functional MALT (transporter) and four functional MALS (maltase/isomaltase) genes. Following duplication, the activity of the MalS paralogs diverged, with Mal12 and Mal32 showing activity towards α 1-4 glycosides like maltose, and Ima1 and Ima5 hydrolyzing α 1-6 glycosides like isomaltose and palatinose. The two MalT paralogs show a lower degree of specialization, with Mal31 exclusively transporting α 1-4 glycosides, and Mal11 transporting both α 1-4 and α 1-6 disaccharides 7,36.

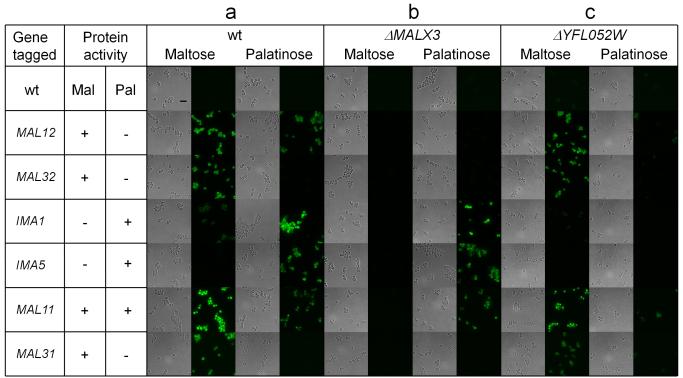

We first investigated whether expression of different MALS and MALT genes is regulated specifically by the sugar they show activity for. We therefore fluorescently tagged each of the four MALS and two MALT target genes in the wild type (wt) strain and evaluated their expression in medium containing either maltose (α 1-4 disaccharide) or palatinose (α 1-6 disaccharide) using fluorescence microscopy. Figure 1a shows that MAL gene regulation in S. cerevisiae is specific: most of the genes are only activated in presence of their respective substrate sugars (maltose or palatinose), and not in presence of the sugar for which they do not show activity. One notable exception is the MAL12 hydrolase gene, which shows activity towards α 1-4 disaccharides, but also seems to be activated by the α 1-6 disaccharide palatinose. However, this gene shares a bidirectional promoter with the MAL11 transporter gene, which transports both types of disaccharides. Hence, the a-specific activation of MAL12 in palatinose may be a consequence of the need to activate MAL11, which encodes the only transporter that allows uptake of α 1-6 disaccharides like palatinose.

Figure 1. Maltose and isomaltose-specific genes are differentially regulated.

Representative brightfield and fluorescence microscopy images of yeast cells with various MALS or MALT genes fluorescently tagged are shown for wt cells (a), and strains carrying deletions of genes encoding transcriptional regulators (panel b: MALX3, panel c: YFL052W). Cells were grown in presence of either palatinose (α 1-6 disaccharide) or maltose (α 1-4 disaccharide) as indicated above the pictures. Gene names are listed in the first column, and protein activities towards the two types of sugars (maltose or palatinose) are indicated in the second and third columns. Scale bar is included in the upper left image and equals 10 μm. The experiment was repeated at least three times.

We have demonstrated previously that the MALR transcription factor genes MALX3 and YFL052W are crucial for growth on maltose and palatinose respectively 36. To further investigate which of these transcriptional regulator genes is responsible for activation of which target gene(s), we deleted these MALR genes and investigated the effect on MALT and MALS activation. Deletion of MALX3 (Fig. 1b) abolishes the expression of the maltose-specific hydrolase genes MAL12 and MAL32, and the maltose-specific transporter gene MAL31. Moreover, the MAL11 gene encoding the promiscuous transporter capable of transporting both α 1-4 and α 1-6 disaccharides is also no longer expressed in the presence of maltose, even though it is still activated in palatinose. Expression of IMA1 and IMA5 encoding α 1-6 hydrolases is not affected by deletion of MALX3. By contrast, deletion of the second MALR gene, YFL052W, abolishes expression of IMA1 and IMA5 (Fig. 1c), while the maltose-induced expression of genes encoding α 1-4-specific proteins (MAL12, MAL32, MAL31) and the promiscuous MAL11 is not affected.

Different MalR regulators bind different DNA sites

The previous results demonstrate that the MALS and MALT genes are regulated by two distinct regulatory networks, governed by different MalR transcription factors in response to different disaccharides. The limited crosstalk between the two regulatory networks suggests that the maltose- and palatinose-specific MalR regulators bind different DNA binding sites. To test this, we determined the DNA binding sites of the palatinose-specific regulator Yfl052w using the ChIP-exo technique 38, and compared these to the known binding sites of the maltose-specific regulator Malx3 39. The ChIP-exo analysis supports the results reported in Fig. 1 and indicates that both transcription factors bind different sites. Specifically, when the α 1-6 disaccharide palatinose is present, Yfl052w binds the promoter regions of palatinose-specific genes (IMA1, IMA5, YFL052W) and the MAL11 promiscuous transporter, but not the promoters of maltose–specific genes (Supplementary Fig. 1). Instead, these maltose-specific genes are known to be bound by Malx3 in the presence of maltose 39

Additionally, two novel noncanonical targets of Yfl052w were identified in the ChIP-exo experiment - YHR210C and YJL217W (Supplementary Fig. 1). Both of these genes seem to have no role in α-disaccharide metabolism and they do not show sequence similarity with MAL genes. Deletion of any of the two does not change cell growth or expression patterns of the other MAL genes (IMA5 and MAL32) in palatinose or in maltose (Supplementary figure 2).

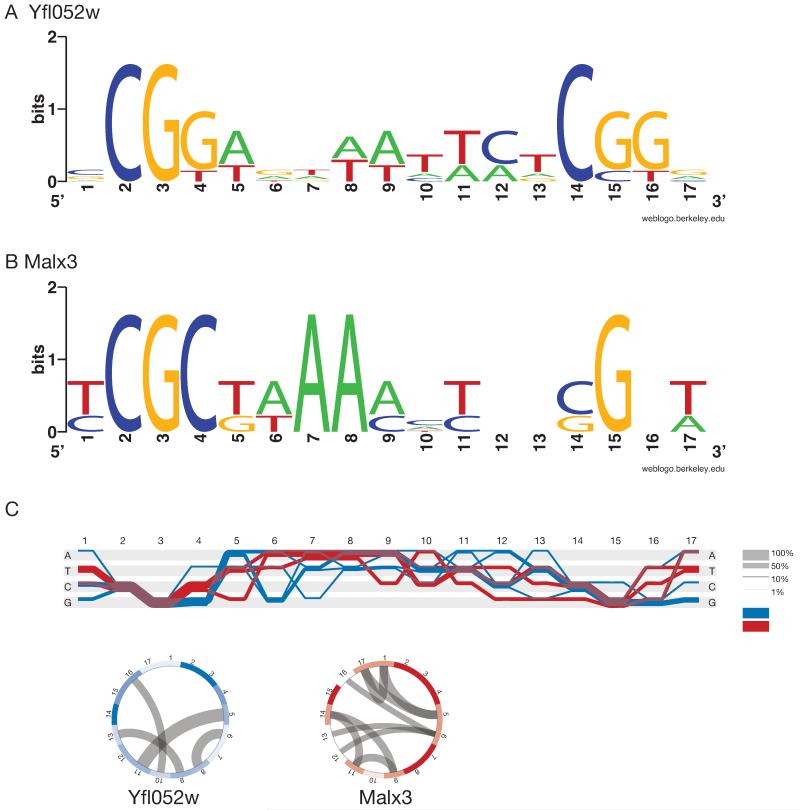

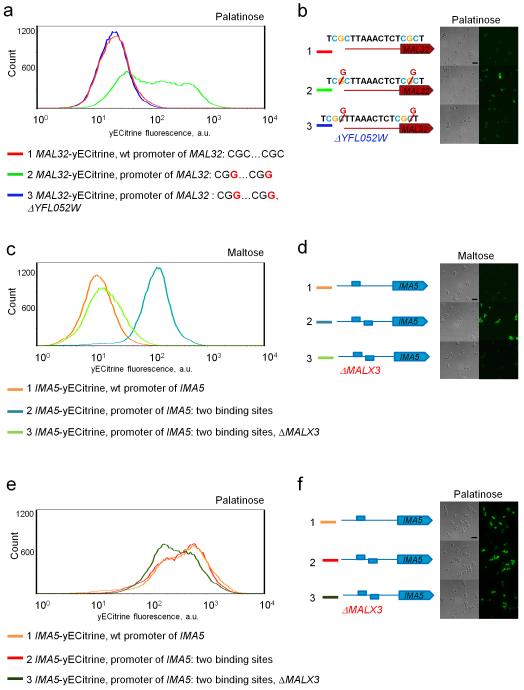

The MalR regulators belong to a family of fungal Zn-finger transcription factors, which typically bind short three-nucleotide CG-rich motifs separated by a spacer of fixed length 40. Fig. 2 shows that the DNA binding site of the palatinose-specific Yfl052w regulator is very similar to that of the maltose-specific Malx3 regulator. Specifically, the Yfl052w binding site consists of two CGG motifs separated by a 9 nt AT-rich spacer (Fig. 2a), while Malx3 DNA binding sites contain a CGC motif, a 9 nt spacer and a CGN motif (Fig. 2b). To confirm the binding sites of the different MalR regulators (Malx3 and Yfl052w), we first deleted the binding sites in a strain carrying a fluorescent reporter fusion of a maltose-specific target gene (MAL32) and in a strain carrying a reporter for a palatinose-specific gene (IMA5). In both cases, deletion of the respective binding sites abolished induction of the target gene by its respective substrate sugar (Fig. 3a lines 1 and 2 and Fig. 3b lines 1, 2 and 3). Moreover, replacing one binding site with the other switches the sugar-specificity of the promoters as well as the specific transcription factor needed to activate the reporter gene (Fig. 3), further suggesting that these slightly different binding sites separate the two regulatory circuits. Finally, to further confirm that this single nucleotide difference is indeed responsible for the different binding of both classes of transcription factors, we introduced a double point mutation in the promoter region of MAL32 gene, so that both CGC motifs in the Malx3 binding site were changed to CGG motifs. As shown in Fig. 4a,b, these mutations result in MAL32 gene expression in presence of palatinose, and this effect was dependent on the YFL052W gene.

Figure 2. Different DNA-binding specificity of different MalR transcription factors.

(a) Sequence logo of Yfl052w DNA binding site CGG(9N)CGG. (b) Sequence logo of Malx3 DNA binding site CGC(9N)CGN. (c) Sequence Diversity Diagram conveying differences and similarities between Yfl052w (blue) and Malx3 (red) binding sites. Regions where two groups overlap are shown in purple. Thickness of the line shows the relative proportion of the aligned sequences. Positions that differentiate two groups are identified by a separation of blue and red lines. The rings below are basic heatmaps in circular layout showing the information content of the positions. The more saturated the color, the higher the information content, thus indicating conserved regions. Mutual information (MI) represents covariance of positions and is shown as grey lines inside the circles. High MI indicates the dependency of one position on another.

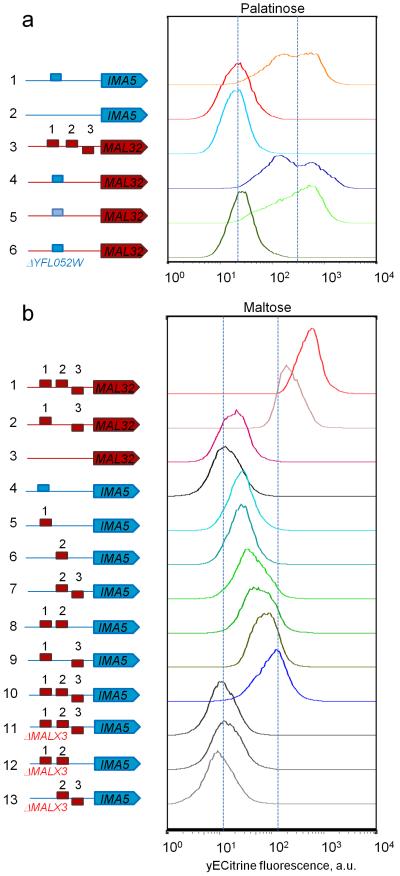

Figure 3. Maltose and palatinose-specific MalR regulators have different DNA binding sites.

Representative flow cytometry histograms of populations of fluorescent reporter strains carrying different types of DNA binding sites in the promoters of a maltose-specific gene MAL32 (red block arrow), or a palatinose-specific IMA5 (blue block arrow), grown in maltose or palatinose. CGG-containing binding sites found in promoters of palatinose-specific genes are depicted as blue rectangles, CGC-containing DNA binding sites found in promoters of maltose-specific gene are depicted as red rectangles. (a) DNA-binding specificity of the palatinose-specific regulator Yfl052w. (1) A fluorescently-tagged IMA5 gene under its native promoter shows a normal level of IMA5 expression activated by Yfl052w in palatinose. (2) Deletion of the Yfl052w binding site abolishes the expression of IMA5. (3) A fluorescently-tagged maltose-specific MAL32 under its native promoter shows no expression on palatinose and is used to quantify autofluorescence. Introduction of a Yfl052w binding site from the promoter of IMA5 (4) or IMA1 (5) in front of the fluorescently-tagged MAL32 gene makes the expression of this gene responsive to palatinose. (6) Deletion of YFL052W abolishes the expression of the MAL32 gene from (4). (b) DNA-binding specificity of the maltose-specific regulator Malx3. (1) A fluorescently-tagged MAL32 under its native promoter shows a normal level of MAL32 expression activated by Malx3 in maltose. (2) Deletion of one Malx3 binding site decreases the expression levels of fluorescently-labeled MAL32. (3) Deletion of all three Malx3 binding sites abolishes the expression of MAL32. (4) A fluorescently tagged IMA5 gene under its native promoter is used to show autofluorescence. Introduction of one (5),(6), two (7)-(9) or three (10) Malx3 binding sites in the promoter region of a fluorescently-tagged IMA5 gene makes the expression of this gene responsive to maltose, with increasing number of binding sites resulting in higher expression levels. (11)-(13) Deletion of the maltose-specific regulator MALX3 abolishes the expression of strains from (7),(8),(10). Each experiment was repeated at least three times with two biological replicates.

Figure 4. Yfl052w and Malx3 regulators show different DNA-binding specificity.

(a) Two point mutations in a maltose-inducible promoter yield a palatinose-inducible promoter. (1) Histogram of the fluorescence signal of a strain with a yECitrine-tagged MAL32 gene. This maltose-specific reporter gene shows no expression in palatinose and can be used to estimate the background fluorescence levels. (2) Single nucleotide C to G substitution in both CGC motifs in the upstream Malx3 binding site of the of MAL32 promoter leads to expression of this gene in palatinose. (3) Deletion of palatinose-specific regulator Yfl052w abolishes the expression of the mutant promoter. (b) Fluorescence microscopy images of the same strains reported in panel (a). (c) Increasing the number of CGG-containing binding sites in a palatinose-inducible promoter yields a promoter that is responsive to maltose. (d) Representative fluorescence microscopy images of the strains shown in panel (c) in maltose. (e) Increasing the number of CGG-containing binding sites does not affect the expression of the palatinose-inducible gene IMA5 in palatinose. (f) Representative fluorescence microscopy images of the strains shown in panel C in palatinose. Scale bar is included in the upper left image of panels (b), (d), (f) and equals 10 μm. Each experiment was repeated at least three times with two biological replicates.

Apart from the one-nucleotide difference between the binding motifs, we also noticed that the promoters of maltose-specific genes (MAL12, MAL32, MAL31) and the promiscuous MAL11 transporter always contain three Malx3 binding sites, while palatinose-specific genes (IMA1, IMA5, YFL052W) contain only one Yfl052w binding site. Interestingly, the results shown in Fig. 3 suggest that all three Malx3 binding sites are necessary to obtain full activation of the downstream gene, with one or even two binding sites only yielding partial activation.

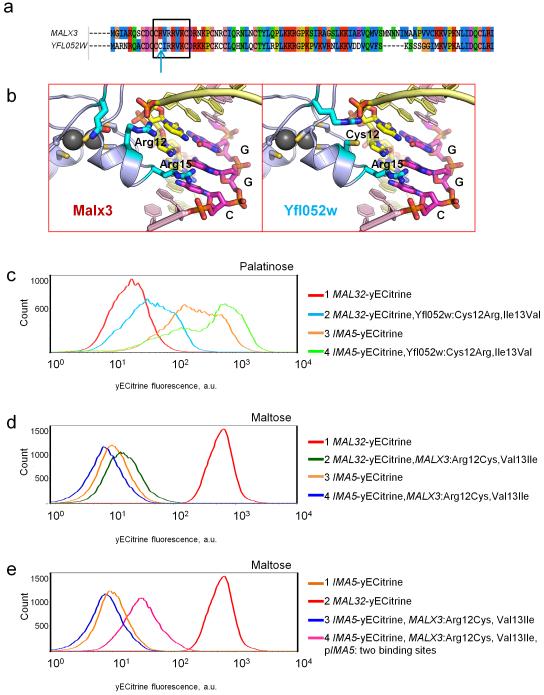

Two key amino acid substitutions in the DNA-binding domain of Yfl052w regulator are responsible for its altered DNA-binding preference

Next, we turned our attention to the MalR transcription factors. To determine which amino acid residues of palatinose-specific regulator Yfl052w could be responsible for its altered DNA-binding specificity, we modeled the three-dimensional structures of Yfl052w and Malx3 in complex with their DNA binding sites (Fig. 5). Our model suggests that the amino acid in position 12 may explain the difference in DNA-binding preference between Malx3 and Yfl052w. In Malx3, position 12 is occupied by Arg, which is not involved in the base pair recognition, but does interact with the negatively-charged phosphate backbone of DNA. In Yfl052w, position 12 is taken by a Cys residue, which in contrast to the Arg residue in Malx3 does interact with the bases of the DNA binding motif and specifically requires the presence of a G in the third position of CGG motif (Fig. 5b). In addition, Val in position 13 in Malx3 is substituted with Ile in Yfl052w. Both Val and Ile provide the hydrophobic environment required for amino acid in position 12. However, the Cys residue needs to be accompanied by a more hydrophobic amino acid, which might explain the exchange of Val (hydrophobicity index 79) to Ile (100).

Figure 5. Differences in the DNA-binding domain of Malx3 and Yfl052w explain their different binding specificity.

(a) Alignment of the Malx3 and Yfl052w DNA-binding domains. Amino acids predicted to interact with the DNA binding site are indicated with a black rectangle. The key position 12 that differs between Malx3 and Yfl052w is highlighted with a blue arrow. (b) Molecular modelling of the interaction between the Zn-finger domain and its DNA binding site. Important base pairs are represented as yellow and magenta sticks, important amino acids are represented as blue sticks. The Arg15 is shared between both transcription factors and is responsible for the recognition of the G in the middle of the CGG binding motif. Arg12 in Malx3 does not take part in recognition of the CGG motif, but Cys12 in Yfl052w does interact with the DNA and is responsible for the preference for a G nucleotide in the third position of the motif. (c) A mutated version of the palatinose-specific Yfl052 activator (Cys12Arg and Ile13Val) is able to partly activate the MAL32 promoter in response to palatinose and also retains its capacity to activate the IMA5 promoter. (d) A mutated version of the maltose-specific Malx3 activator (Arg12Cys and Val13Ile) is incapable to activate MAL32 or IMA5 in response to maltose. (e) A mutated version of the maltose-specific Malx3 activator (Arg12Cys and Val13Ile) is capable to partly activate an IMA5 promoter containing an additional Yfl052w binding site. Each experiment was repeated at least three times with two biological replicates.

To confirm whether the preference of Yfl052w to CGG motifs is indeed dictated by the two residues mentioned above, we mutated Cys12 in Yfl052w to Arg, and Ile13 to Val and tested the binding specificity of this mutated Yfl052w. As shown on Fig. 5c, the mutated Yfl052w is able to partially activate the expression of maltose-specific gene MAL32 in palatinose. Moreover, the fluorescence profile of these cells resembles that of wt cells with fluorescently tagged IMA5, which is also activated by Yfl052w. Interestingly, the mutated Yfl052w apparently also still activates its natural target promoter that drives IMA5.

Similarly, we introduced Arg12 to Cys and Val13 to Ile mutations in the Malx3 regulator. This mutated Malx3 regulator can no longer activate expression of its natural target MAL32 promoter (containing CGC-motifs), nor can it activate the palatinose-specific IMA5 gene (Fig. 5d). However, we showed earlier that Malx3 requires several DNA binding sites in order to activate expression of its target genes (Fig. 3b). Indeed, when a second CGG-containing binding site was introduced in the promoter of a fluorescently labeled IMA5 reporter strain, the mutated Malx3 was able to activate the expression of IMA5 in maltose, which is in keeping with the observation that Malx3 requires multiple binding sites (Fig. 5e).

Malx3 binds both CGC and CGG motifs

Structural modeling of Malx3 bound to DNA predicts that Malx3 is promiscuous and can bind both CGC and CGG motifs. This reduced binding stringency compared to Yfl052w is predicted to be a result of the Arg12 residue in the Malx3 binding domain, which allows both C and G in the third position of the binding motif. This prediction is supported by the observation that Yfl052w carrying a Cys12Arg substitution still activates expression of its natural target IMA5 that carries CGG motifs in its promoter (Fig. 5c). On the other hand, the results shown in Fig. 1 demonstrate that Malx3 does not activate expression from CGG-containing promoters of palatinose-specific target genes in vivo. However, the results from Fig. 3b show that Malx3 requires the presence of more than one binding site to activate expression, and promoters of palatinose-specific genes only contain one MalR binding site. In other words, whereas Malx3 is able to bind both CGG and CGC motifs, Malx3 may not be able to activate CGG-containing palatinose-specific promoters because they only contain one binding site; whereas maltose-specific promoters contain multiple sites. To verify this hypothesis, we introduced a second CGG-containing Yfl052w binding site in the promoter region of the fluorescently labeled IMA5 gene and measured the expression of this palatinose-specific gene in the presence of maltose. As shown in Fig. 4c,d, the introduction of an additional binding site leads to the activation of IMA5 gene expression by maltose to a level similar to its normal activation in palatinose, even in the absence of the Yfl052w transcription factor that normally activates IMA5.

Together, these results suggest that specific binding of Yfl052w to the promoter regions of palatinose-specific target genes is determined by the presence of CGG motifs. Promoters of maltose-specific genes contain CGC motifs and thus cannot be bound by Yfl052w because the Cys12 residue in the DNA-binding domain of this regulator prevents binding CGC sites. On the other hand, Malx3 is capable of binding both types of motifs (CGG and CGC), but requires the presence of several binding sites in the same promoter region to yield full gene activation. This prevents Malx3 from activating expression of palatinose-specific genes, which carry only one MalR binding site in their promoters.

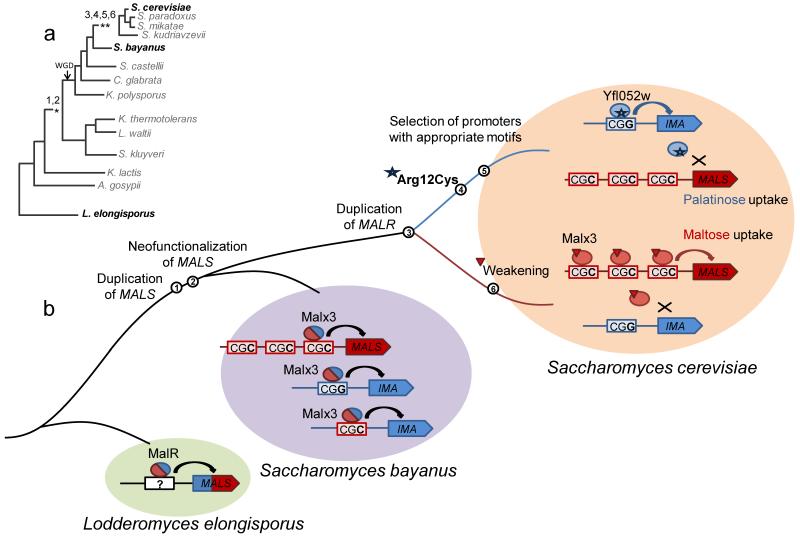

Evolutionary model of divergence of two regulatory networks

Taken together, our results uncover the mechanistic details underlying the emergence of two separate and specific regulatory circuits, one regulating maltose metabolism and the other regulating isomaltose and palatinose metabolism. We next wanted to establish the likely evolutionary path from the ancestral, pre-duplication circuit to the present-day situation.

The common ancestor of extant yeast species only had one copy of each of the three types of MAL genes (MALS, MALT and MALR)7,36. In some species, including S. cerevisiae, the MAL genes underwent several duplication events. In other species, like L. elongisporus, the MAL genes were not duplicated and the ancient, simple three-gene network seems to be preserved (Supplementary Fig. 3). Moreover, the activity of the MalS protein of L. elongisporus resembles that of the pre-duplication ancestral enzyme and can hydrolyze both maltose- and palatinose-like disaccharides 7. This suggests that its MalR regulator may be able to activate the expression of both the promiscuous MalS and the promiscuous MalT in presence of any of the two types of sugars. To test this hypothesis, we compared mRNA levels of MALS and MALT genes in L. elongisporus cells grown on either maltose, palatinose or glucose. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 4, expression of MALT and MALS is indeed activated in presence of both maltose and palatinose, but not glucose.

Next, we investigated the timing of the duplication and divergence of the MALS and MALR genes (Supplementary Fig. 3). We have previously shown that the MALS genes duplicated and acquired a novel function at least at the branching of Kluyveromyces thermotolerans 7. A similar analysis shows that the functional diversification of MALR genes happened later in the evolution, around the branching of S. bayanus from the Saccharomyces clade. Specifically, the genome of S. bayanus contains only one MALR of the promiscuous MALX3-type (Arg in the position 12) and lacks the palatinose-specific Yfl052w-like regulator (containing a Cys12Arg mutation), which is present in S. cerevisiae, S. paradoxus, S. mikatae and S. kudriavzevii. Expression analysis shows that the regulation of different MALS genes in S. bayanus is not specific; that is, maltose-specific and palatinose-specific MALS genes are equally activated in presence of maltose and palatinose, but not glucose (Supplementary Fig. 5). Furthermore, the nucleotide sequences of the MALR binding sites in the genomes of S. bayanus, S. mikatae, S. paradoxus and S. kudriavzevii are remarkably conserved. Similar to the sites in S. cerevisiae, they fall into two classes: CGG- and CGC-containing (Supplementary Data 1). Analogous to S. cerevisiae, in S. mikatae, S. paradoxus and S. kudriavzevii (i.e. species in which the MALR regulator as well as the MALS genes has duplicated and diversified), CGG-containing sites are found in the promoter regions of palatinose-specific genes, and CGC-containing sites are situated upstream of homologs of maltose-specific genes. By contrast, in S. bayanus (which contains multiple MALS, but only one Arg12-type MALR), CGG- and CGC sites are seemingly randomly distributed in the promoters of homologs of the different maltose- as well as palatinose-specific genes (Supplementary Data 1), which agrees with the nonspecific regulation of these genes in S. bayanus.

Together, these observations reveal that the MAL gene network evolved as depicted in Fig. 6. In this model, duplication and functional divergence of the MALS genes already happened in the common ancestor of K. thermotolerans and S. cerevisiae (Fig. 6, events 1and 2), but these genes were still controlled by one promiscuous MalR regulator that resembled today’s S. bayanus Malx3 protein (which has an Arg residue in position 12). Similar to the present-day Malx3 regulator, the ancestral regulator was able to bind both CGG and CGC-motifs and induced the expression of both maltose- and palatinose-specific genes in presence of both types of sugars. The promoters of these genes probably did not yet diverge, with both CGC and CGG motifs present upstream of maltose as well as palatinose-specific genes similar to the genome of present day S. bayanus. Yfl052w-like regulators most probably first appeared later in the evolution as a result of duplication (Fig. 6, event 3) and subsequent mutations, including the key Arg12Cys mutation (Fig. 6, event 4). This mutated Yfl052w-like paralog can no longer bind the CGC motifs, which are selected for in the promoters of maltose-specific genes. By contrast, the Malx3-like regulator evolves a weaker activity, so that it, loses the ability to activate expression of palatinose-specific genes, which are selected to have only one CGG-containing binding site, while retaining the ability to activate maltose-specific promoters that contain three CGC binding sites (Fig. 6, events 5 and 6).

Figure 6. Possible evolutionary mutational path of MAL regulatory network diversification.

(a) Simplified phylogenetic tree of the fungal lineage. The numbers correspond to the key evolutionary events listed in panel (b). WGD denotes the documented whole-genome duplication event in the fungal lineage. (b) Likely evolutionary path of the MAL regulatory network. The path starts from the common ancestor of L. elongisporus, S. bayanus and S. cerevisiae and ends at the modern day S. cerevisiae. In the common ancestor of L. elongisporus, S. bayanus and S. cerevisiae, maltose and isomaltose enzymatic activities are not separated and coexist in a single ancestral MalS enzyme, which is regulated by the single promiscuous MalR regulator. In the common ancestor of S. cerevisiae and K. thermotolerans, the MALS genes duplicated and neofunctionalized (1, 2), so that both types of target genes (maltose and palatinose specific) are present and are regulated by one promiscuous Malx3-like transcription factor that has an Arg residue at position 12 allowing it to bind both CGG and CGC motifs. The regulation is not specific at this point, that is, palatinose and maltose specific genes are equally expressed in presence of their respective substrate as well as a non-specific disaccharide (as it is in S. bayanus). Two separate regulatory circuits appear around the deviation of S. bayanus from the Saccharomyces tree. The MALR gene is duplicated (3) and this duplication event is followed by two single nucleotide mutations in the first positions of the Arg12 and Val13 codons, changing these to Cys and Ile in one of the paralogs (4), thus preventing it from binding CGC motifs in the promoters of maltose specific genes. Analysis of genomes that carry only one type MALR gene suggests that in the ancestral yeast CGG and CGC motifs were randomly distributed among maltose- and palatinose-specific genes. This implies that these binding sites needed to change in concert with the mutations in the MALR paralogs, so that palatinose-specific genes only contain one CGG site, and maltose-specific genes contain three CGC motifs so that they can still be activated by the weakened Malx3 paralog (5, 6).

Discussion

Several studies have investigated the regulatory divergence between species on a genome-wide level8,12,18,20,22,41-48. Together, these studies show that changes in gene regulation occur frequently and are important drivers of functional and morphological evolution 26,46,47. This is especially true for the evolution of the regulation of newly duplicated genes. Since paralogs often evolve different functions, these functionally diverged duplicates may need to be regulated independently. However, despite the importance of the evolution and divergence of gene regulation, the exact molecular mechanisms and mutational pathways that lead to the emergence of such novel regulatory networks remain largely unknown.

Our results show how duplication of a promiscuous transcription factor and its target genes led to the development of two separate regulatory networks, with one paralog of the transcription factor regulating a set of target genes involved in maltose uptake and metabolism, and another regulating target genes responsible for palatinose consumption. Specifically, we find that only two point mutations in the promoter regions of the target genes, combined with two single-nucleotide mutations in the DNA-binding domain of the transcription factor paralogs are sufficient to ensure that each transcription factor paralog specifically activates its target promoters, without interfering with the regulation of the target genes of the other paralog.

While the predominant opinion in the field is that evolution on the regulatory level precedes the actual changes in the protein sequence of the target genes 8,10,18,21,22,25,49, our data indicate that the opposite is also possible. It seems likely that the pre-duplication ancestral MAL gene regulatory network was very simple and resembled the network in present-day L. elongisporus (Supplementary Fig. 3). The L. elongisporus MalR regulator is promiscuous and activates expression of a (bifunctional) MalS hydrolase and a transporter in response to either maltose or palatinose. Several duplication events of MALS genes followed by optimization of either maltase or palatinase activity in different paralogs led to emergence of two functional classes of MalS hydrolases in S. cerevisiae7. Interestingly, our analyses suggest that the specialization of palatinose-specific MalR regulators and the separation of the two regulatory networks likely occurred after the neofunctionalization of MALS target genes, around the branching of the S. bayanus and S. cerevisiae clades (Supplementary Fig. 3). The functional divergence of the MalS enzymes generated a situation where it became beneficial for the cells to regulate each of the MalS enzymes separately, so that each enzyme is only activated by its proper substrate and paralog interference is avoided. In keeping with this hypothesis, we have previously shown that activation of MAL genes in conditions where they are not required comes at a considerable fitness cost 50.

The evolutionary path described in our study highlights how promiscuity (or limited binding site specificity) may increase the “evolvability” of transcription factors by facilitating the emergence of distinct regulatory modules. Indeed, following a duplication event, successive mutations may allow a gradual increase in the specificity of the newly duplicated transcription factor paralogs and promote a smooth emergence of two independent regulatory circuits while avoiding misregulation of the target genes during this process (i.e. a so-called “fitness valley” is avoided). Importantly, only two key mutations in the Zn-finger DNA binding domain are needed to increase the binding specificity of the Yfl052w paralog. Together, these observations reveal how the seemingly unlikely model for the emergence of a new regulatory module through duplication of a transcription factor proposed by Babu and Teichmann12 can in fact really occur. However, in contrast with the theory that regulation evolves a-symmetrically, with only the regulation of the new function diverging from that of the ancestral function15, we find that in this case the evolution of two separated regulatory networks depends on concerted changes in both networks (one regulating α 1–4 glycoside metabolism, and the other regulating α 1–6 glycoside metabolism).

Interestingly, the importance of promiscuity also emerges from other studies that investigate the evolution of other proteins, such as enzymes and receptors. For example, the ancestral pre-duplication maltase showed activity towards both α 1–4 glycosides like maltose, but also a (trace) activity for α 1–6 glycosides such as isomaltose. Similarly, promiscuity has also been shown in other pre-duplication ancestral genes 2,51,52. Hence, whereas promiscuity and “side activities” are often regarded as imperfections, they are emerging as crucial factors that promote “evolvability” because the side-activities can be selected for and drive the evolution of a paralog after duplication 53.

It is especially interesting to compare our results to those reported in a recent elegant study by Baker and coworkers17. These researchers showed how duplication of the ancestral fungal Mcm1 transcription factor resulted in two paralogs that each evolved to regulate a subset of the original target genes. In contrast to the MAL gene system, the Mcm1 target genes were not duplicated, and duplication of the Mcm1 factor did not lead to the development of a completely separate regulatory circuit, but rather resulted in subfunctionalization and rewiring of the existing network, with the two paralogs diverging to regulate a subset of the original target genes. Moreover, whereas the MalR paralogs evolved different DNA binding sites, the Mcm1 paralogs primarily evolved specificity through mutations that restrict their interaction with other transcription factors (Arg81 and Matα1), showing that this is a possible alternative route to rewire networks.

At first sight, the scenario of the evolution of the MAL genes, where both a transcription factor and its targets are duplicated, might seem rare. However, such situations may occur relatively frequently, either independently, or as a result of whole genome duplication events8,19,54,55. Interestingly, the fungal lineage shows evidence for at least one whole-genome duplication event34,56 (see Supplementary Fig. 3). Several authors suggested that post whole-genome duplication networks may undergo functional partitioning, with the paralogs forming two independent subnetworks, which resembles the MAL gene scenario8,19. Moreover, a number of studies report that after the whole-genome duplication, the regulatory genes are preferentially retained comparing to other functional classes of genes2,31-33,35. However, in the case of the MAL genes, the observed duplication events do not coincide with the reported whole-genome duplication event and instead seem to be the results of (multiple) independent duplications of smaller chromosomal regions. Interestingly, Lynch and Katju proposed that such small-scale duplications might result in misregulation of the duplicated gene when the respective promoter region is not duplicated57. However, in the case of the MAL genes, the duplication events probably included the regulatory regions of the duplicated genes, as well as a (subsequent) duplication of the gene encoding the Mal regulator. While such events may be more rare than those associated with whole-genome duplications, they may occur relatively frequently in subtelomeric regions36. Moreover, many transcription factors show some level of promiscuity in their recognition of target sites58,59. As detailed above, such promiscuity may greatly facilitate the expansion and rewiring of transcriptional networks. Hence, whereas the molecular details may differ, the general themes uncovered in this study of the MAL regulatory circuit may be representative for a large number of similar events throughout the tree of life.

Methods

Strain construction

A complete list of strains and plasmids used in this study is listed in Supplementary Data 2. The primers used to make and confirm these strains can also be found in Supplementary Data 2. All constructs were verified by Sanger sequencing or/and PCR.

Microbial strains, plasmids and growth conditions

We showed earlier that the S. cerevisiae feral isolates RM11 (from a vineyard) and YJM789 (from an AIDS patient) as well as laboratory strain EM93, ancestral to S288c, can ferment maltose due to the presence of a MALX3 regulator in their genomes 36; whereas S. cerevisiae strain S288c lost its MALX3 regulator together with the ability to grow on maltose. We re-introduced MALX3 in the genome of S. cerevisiae S288c to restore its ability for growth on maltose and named the resulting strain KV5000. Therefore, KV5000 represents a reconstituted wild-type S. cerevisiae strain, and for this reason, we refer to this strain as the wild-type (WT) strain.

Yeast cultures were grown in rich YP media consisting of 2% peptone (Difco), 1% yeast extract (Difco), and 2% sugar (Sigma-Aldrich) at 30°C in a rotating wheel or shaking incubator. The sugars used in this study were purchased to their highest available purity and were filter-sterilized before adding to rich media. Plasmid sets were obtained from EUROSCARF (http://web.unifrankfurt.de/fb15/mikro/euroscarf/) for reusable markers (Deletion Marker Plasmids) and overexpression/epitope tagging 60. Plasmids were used as indicated by the manufacturer.

Fluorescent microscopy imaging

Cell were pre-grown overnight in YPD 2% glucose medium and then transferred to YP media supplemented with either palatinose (2%) or maltose (2%) for another 16 hours. The acquisition of the images was done with the Optomorph software (version 1.0.2) in combination with a Nikon Eclipse Ti microscope equipped with a DL-604M-#VP camera (Andor™ technology). Images were processed and scaled with ImageJ software.

Flow cytometry to measure gene expression levels

Cell were grown in YP medium supplemented with maltose (2%) or palatinose (2%) till the OD600=0.1. Fluorescent histograms were acquired using a BD Biosciences Influx flow cytometer with 488 nm laser coupled to 530-540 nm detector.

RNA isolation and qPCR

RNA was isolated with phenol/chloroform. Genomic DNA elimination and reverse transcription was performed using the QIAGEN QuantiTech Reverse Transcription kit according to manufacturer’s instructions. AB Power SYBR Green PCR master mix was used for qPCR.

Modelling

To investigate the difference between the MalR proteins homology models were constructed. As there are no homologoes template structures available for the C-terminal domain, only the N-terminal DNA binding region was investigated. Sequence comparison and fold recognition using Phyre2 indicated pdb entry 1D66 (Gal4-DNA complex) as the most suitable template40,61. All complexes were modelled using the homology implementation in the Molecular Operating Environment (MOE, Chemical Computing group, Montreal, Canada) with the implemented CHARMM force field in the presence of the 1D66 DNA structure 62. Prior to modelling complexes, the base pair sequence of 1D66 sequence was adapted according to the MalR recognition motifs. Following the homology modelling incorporating the DNA structures the complex was optimized by steepest descent minimization in the presence of explicit water molecules.

ChIP-exo

ChIP-exo was performed following the Pugh’s lab protocol 63 by Peconics LLT, USA and independently repeated by EMBL GeneCore, Germany. KP54 strain with HA-tagged Yfl052W was used for analysis. Untagged strain KP52 served as a control. DNA-protein complexes were precipitated using the Roche Anti-HA high affinity rat monoclonal antibody (clone 3F10).

Chip-exo data analysis

After Illumina sequencing, low quality reads (q< 30) and adaptor sequences were first trimmed by using Trim Galore! (http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/trim_galore/). Resulting reads were then mapped to the S. cerevisiae reference genome (S288C, R64-1-1) by BWA version 0.7.4 64 with default parameters. BAM-formatted files were then generated using samtools version 0.1.18 (The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools) and further sorted following chromosome order by picard version 1.100 (http://picard.sourceforge.net). GEM (Genome wide Event finding and Motif discovery) version 2.41 was used to detect the positive peak and motif discovery 65. Default parameters were used except -- k_min was set to 5, -- k_max was set to 15, --s was set to 10,000,000 and --smooth was set to 3, respectively. After comparing the experimental sample with the control, the coordinate from resulted peaks were then visualized by using IGV 2.3 to confirm the accuracy 66.

Bioinformatics analyses

Genomic sequences of S. cerevisiae S288C, S. mikatae IFO 1815 (AABZ00000000.1), S. kudriavzevii IFO 1802 (AACI00000000.3), S. paradoxus NRRL Y-17217 (AABY00000000.1), L. elongisporus NRRL YB-4239 (AAPO00000000.1) were downloaded from the National Center for Biotechnology Information. S. bayanus CBS7001 genomic sequence is downloaded from www.SaccharomycesSensuStricto.org. Homologs of different MalR, MalS and MalT genes were identified with local BLAST+ suite. Upstream regions (−800;0 nt from the translation start) of found homologs were used to determine possible MalR DNA binding sites. Protein alignment and Ks score calculations were performed using MEGA software (version 5.2).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

KP acknowledges financial support from TRIPLE I and a Belspo mobility grant from the Belgian Federal Science Policy Office co-funded by the Marie Curie Actions from the European Commission. Research in the lab of KJV is supported by ERC Starting Grant 241426, HFSP program grant RGP0050/2013, VIB, EMBO YIP program, KU Leuven Program Financing, FWO, and IWT. AV acknowledges RIKEN for the FPR grant. The work of FK was supported by a grant of the HHMI International Early Career Scientist Program (grant #55007424), the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (grant #BFU2012-31329) as part of the EMBO YIP program, two grants from the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness, “Centro de Excelencia Severo Ochoa 2013 - 2017 (grant #Sev-2012-0208)” and (grant #BES-2013-064004) funded by the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), the European Union and the European Research Council (grant #335980_EinME). KV is supported by an FWO postdoctoral fellowship. Funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Competing Financial Interests: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Accession codes: The sequences generated in the ChIP-exo experiment have been deposited in Gene Expression Omnibus database under the accession code GSE57902.

References

- 1.Chen S, Zhang YE, Long M. New genes in Drosophila quickly become essential. Science. 2010;330:1682–1685. doi: 10.1126/science.1196380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Conant GC, Wolfe KH. Turning a hobby into a job: how duplicated genes find new functions. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2008;9:938–950. doi: 10.1038/nrg2482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Innan H, Kondrashov F. The evolution of gene duplications: classifying and distinguishing between models. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2010;11:97–108. doi: 10.1038/nrg2689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kondrashov FA, Rogozin IB, Wolf YI, Koonin EV. Selection in the evolution of gene duplications. Genome Biol. 2002;3 doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-2-research0008. RESEARCH0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prince VE, Pickett FB. Splitting pairs: the diverging fates of duplicated genes. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2002;3:827–37. doi: 10.1038/nrg928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sidow A. Gen(om)e duplications in the evolution of early vertebrates. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 1996;6:715–722. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(96)80026-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Voordeckers K, et al. Reconstruction of ancestral metabolic enzymes reveals molecular mechanisms underlying evolutionary innovation through gene duplication. PLoS Biol. 2012;10:e1001446. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wapinski I, Pfeffer A, Friedman N, Regev A. Natural history and evolutionary principles of gene duplication in fungi. Nature. 2007;449:54–61. doi: 10.1038/nature06107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang J. Evolution by gene duplication: an update. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2003;18:292–298. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ohno S. Evolution By Gene Duplication. Springer-Verlag; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lynch M. The Evolutionary Fate and Consequences of Duplicate Genes. Science (80-.) 2000;290:1151–1155. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5494.1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teichmann S. a, Babu MM. Gene regulatory network growth by duplication. Nat. Genet. 2004;36:492–6. doi: 10.1038/ng1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Teichmann SA, Park J, Chothia C. Structural assignments to the Mycoplasma genitalium proteins show extensive gene duplications and domain rearrangements. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1998;95:14658–14663. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gough J, Karplus K, Hughey R, Chothia C. Assignment of homology to genome sequences using a library of hidden Markov models that represent all proteins of known structure. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;313:903–919. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gu X, Zhang Z, Huang W. Rapid evolution of expression and regulatory divergences after yeast gene duplication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:707–712. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409186102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gu Z, Rifkin SA, White KP, Li W-H. Duplicate genes increase gene expression diversity within and between species. Nat. Genet. 2004;36:577–579. doi: 10.1038/ng1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baker CR, Hanson-Smith V, Johnson AD. Following gene duplication, paralog interference constrains transcriptional circuit evolution. Science. 2013;342:104–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1240810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thompson D. a, et al. Evolutionary principles of modular gene regulation in yeasts. Elife. 2013;2:e00603. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Conant GC, Wolfe KH. Functional partitioning of yeast co-expression networks after genome duplication. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e109. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tirosh I, Barkai N. Comparative analysis indicates regulatory neofunctionalization of yeast duplicates. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R50. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-4-r50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li W-H, Yang J, Gu X. Expression divergence between duplicate genes. Trends Genet. 2005;21:602–607. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ihmels J, et al. Rewiring of the yeast transcriptional network through the evolution of motif usage. Science. 2005;309:938–40. doi: 10.1126/science.1113833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Papp B, Pál C, Hurst LD. Evolution of cis-regulatory elements in duplicated genes of yeast. Trends Genet. 2003;19:417–422. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(03)00174-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hogues H, et al. Transcription Factor Substitution during the Evolution of Fungal Ribosome Regulation. Mol. Cell. 2008;29:552–562. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prud’homme B, Gompel N, Carroll SB. Emerging principles of regulatory evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104(Suppl):8605–8612. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700488104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arnoult L, et al. Emergence and diversification of fly pigmentation through evolution of a gene regulatory module. Science. 2013;339:1423–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1233749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang Z, Gu J, Gu X. How much expression divergence after yeast gene duplication could be explained by regulatory motif evolution? Trends Genet. 2004;20:403–407. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wapinski I, et al. Gene duplication and the evolution of ribosomal protein gene regulation in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:5505–5510. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911905107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pérez JC, et al. How duplicated transcription regulators can diversify to govern the expression of nonoverlapping sets of genes. Genes Dev. 2014 doi: 10.1101/gad.242271.114. doi:10.1101/gad.242271.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sugino RP, Innan H. Selection for more of the same product as a force to enhance concerted evolution of duplicated genes. Trends Genet. 2006;22:642–4. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2006.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davis JC, Petrov DA. Preferential duplication of conserved proteins in eukaryotic genomes. PLoS Biol. 2004;2 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seoighe C, Wolfe KH. Yeast genome evolution in the post-genome era. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 1999;2:548–554. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(99)00015-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van de Peer Y, Maere S, Meyer A. The evolutionary significance of ancient genome duplications. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009;10:725–732. doi: 10.1038/nrg2600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wolfe KH, Shields DC. Molecular evidence for an ancient duplication of the entire yeast genome. Nature. 1997;387:708–713. doi: 10.1038/42711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blanc G, Wolfe KH. Functional divergence of duplicated genes formed by polyploidy during Arabidopsis evolution. Plant Cell. 2004;16:1679–1691. doi: 10.1105/tpc.021410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brown CA, Murray AW, Verstrepen KJ. Rapid expansion and functional divergence of subtelomeric gene families in yeasts. Curr. Biol. 2010;20:895–903. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chow TH, Sollitti P, Marmur J. Structure of the multigene family of MAL loci in Saccharomyces. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1989;217:60–69. doi: 10.1007/BF00330943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rhee HS, Pugh BF. Comprehensive genome-wide protein-DNA interactions detected at single-nucleotide resolution. Cell. 2011;147:1408–19. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sirenko OI, Ni B, Needleman RB. Purification and binding properties of the Mal63p activator of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr. Genet. 1995;27:509–516. doi: 10.1007/BF00314440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marmorstein R, Carey M, Ptashne M, Harrison SC. DNA recognition by GAL4: structure of a protein-DNA complex. Nature. 1992;356:408–414. doi: 10.1038/356408a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ronald J, Brem RB, Whittle J, Kruglyak L. Local regulatory variation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLoS Genet. 2005;1:e25. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0010025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tirosh I, Reikhav S, Levy AA, Barkai N. A yeast hybrid provides insight into the evolution of gene expression regulation. Science. 2009;324:659–662. doi: 10.1126/science.1169766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Madan Babu M. Evolution of transcription factors and the gene regulatory network in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:1234–1244. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stefflova K, et al. Cooperativity and rapid evolution of cobound transcription factors in closely related mammals. Cell. 2013;154:530–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Odom DT, et al. Tissue-specific transcriptional regulation has diverged significantly between human and mouse. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:730–732. doi: 10.1038/ng2047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reed RD, et al. optix drives the repeated convergent evolution of butterfly wing pattern mimicry. Science. 2011;333:1137–1141. doi: 10.1126/science.1208227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baker CR, Booth LN, Sorrells TR, Johnson AD. Protein Modularity, Cooperative Binding, and Hybrid Regulatory States Underlie Transcriptional Network Diversification. Cell. 2012;151:80–95. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tirosh I, Wong KH, Barkai N, Struhl K. Extensive divergence of yeast stress responses through transitions between induced and constitutive activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2011;108:16693–16698. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113718108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.King M, Wilson a. Evolution at two levels in humans and chimpanzees. Science (80-.) 1975;188:107–116. doi: 10.1126/science.1090005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.New AM, et al. Different Levels of Catabolite Repression Optimize Growth in Stable and Variable Environments. PLoS Biol. 2014;12:e1001764. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Carroll SM, Ortlund EA, Thornton JW. Mechanisms for the evolution of a derived function in the ancestral glucocorticoid receptor. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002117. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bridgham JT, Carroll SM, Thornton JW. Evolution of hormone-receptor complexity by molecular exploitation. Science. 2006;312:97–101. doi: 10.1126/science.1123348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Aharoni A, et al. The “evolvability” of promiscuous protein functions. Nat. Genet. 2005;37:73–76. doi: 10.1038/ng1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gachon CMM, Langlois-Meurinne M, Henry Y, Saindrenan P. Transcriptional co-regulation of secondary metabolism enzymes in Arabidopsis: functional and evolutionary implications. Plant Mol. Biol. 2005;58:229–245. doi: 10.1007/s11103-005-5346-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ward JJ, Thornton JM. Evolutionary models for formation of network motifs and modularity in the Saccharomyces transcription factor network. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2007;3:1993–2002. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kellis M, Birren BW, Lander ES. Proof and evolutionary analysis of ancient genome duplication in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature. 2004;428:617–624. doi: 10.1038/nature02424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lynch M, Katju V. The altered evolutionary trajectories of gene duplicates. Trends Genet. 2004;20:544–549. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stormo GD. DNA binding sites: representation and discovery. Bioinformatics. 2000;16:16–23. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chan SK, Jaffe L, Capovilla M, Botas J, Mann RS. The DNA binding specificity of Ultrabithorax is modulated by cooperative interactions with extradenticle, another homeoprotein. Cell. 1994;78:603–15. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90525-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Janke C, et al. A versatile toolbox for PCR-based tagging of yeast genes: new fluorescent proteins, more markers and promoter substitution cassettes. Yeast. 2004;21:947–962. doi: 10.1002/yea.1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kelley LA, Sternberg MJE. Protein structure prediction on the Web: a case study using the Phyre server. Nat. Protoc. 2009;4:363–371. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vanommeslaeghe K, et al. CHARMM general force field: A force field for drug-like molecules compatible with the CHARMM all-atom additive biological force fields. J. Comput. Chem. 2010;31:671–690. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rhee HS, Pugh BF. ChIP-exo method for identifying genomic location of DNA-binding proteins with near-single-nucleotide accuracy. Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol. 2012 doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb2124s100. Chapter 21, Unit 21.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Guo Y, Mahony S, Gifford DK. High Resolution Genome Wide Binding Event Finding and Motif Discovery Reveals Transcription Factor Spatial Binding Constraints. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2012;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Thorvaldsdóttir H, Robinson JT, Mesirov JP. Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV): high-performance genomics data visualization and exploration. Brief. Bioinform. 2013;14:178–92. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbs017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.