Abstract

Cataract surgery is the most frequently undertaken NHS surgical procedure. Visual acuity (VA) provides a poor indication of visual difficulty in a complex visual world. In the absence of a suitable outcome metric recent efforts have been directed towards development of a cataract patient reported outcome measure (PROM) of sufficient brevity, precision and responsiveness to be implementable in routine high volume clinical services.

Aim

To compare and contrast the two most promising candidate PROMs for routine cataract surgery.

Method

The psychometric performance and patient acceptability of the recently UK developed five item Cat-PROM5 questionnaire was compared with the English translation of the Swedish nine item Catquest-9SF using Rasch based performance metrics and qualitative semi-structured interviews.

Results

Rasch based performance was assessed in 822 typical NHS cataract surgery patients across 4 centres in England. Both questionnaires demonstrated good to excellent performance for all metrics assessed, including Person Reliability Indices of 0.90 (Cat PROM5) and 0.88 (Catquest-9SF), responsiveness to surgery (Cohen’s standardized effect size) 1.45SD (Cat-PROM5) and 1.47SD (Catquest-9SF) and they were highly correlated with each other (R=0.85). Qualitative assessments confirmed that both questionnaires were acceptable to patients, including in the presence of ocular comorbidities. Preferences were expressed for the shorter Cat-PROM5 which allowed patients to map their own issues to the questions as opposed to the more restrictive specific scenarios of Catquest-9SF.

Conclusion

The recently UK developed Cat-PROM5 cataract surgery questionnaire is shorter, with performance and patient acceptability at least as good or better than the previous ‘best of class’ Catquest-9SF instrument.

Keywords: Cataract surgery, Patient reported outcome measure, PROM, Rasch analysis, Cat PROM5, Catquest-9SF

Introduction

Cataract is a common potentially blinding eye disease1 with an adverse impact on quality of life2 for which surgical intervention is currently the only effective treatment. In England during the 2015-2016 year there were over 390,000 cataract operations undertaken in the UK National Health Service (NHS), representing a crude rate of around 7.0 per 1000 population, with in addition over 13,000 post-cataract posterior capsulotomies3, at a combined estimated cost of approximately £400 million.

In the face of high demand, shrinking NHS resources and variations in eye care4 5, taking account of the overall impact of cataract on a patient’s life is of increasing importance6. The 2017 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) cataract surgery guideline (NG77) and the Royal College of Ophthalmologists 2015 cataract surgery commissioning guideline both recommend further research into self-reported measures of visual disability caused by cataract, including patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) for cataract surgery. In addition to the usual requirements of validity and robust psychometric performance2 a NHS-suitable cataract surgery PROM would need to be brief to be implementable in high volume service environments. Among the various measures two instruments appear to be the most promising candidates: the English translation of the Swedish Catquest 9SF 7 8, and the more recently UK developed Cat PROM59. Each are short, psychometrically robust instruments validated in English-speaking contexts9 10. In this report we compare and contrast their performance and relative merits in a group of typical UK cataract patients in 4 NHS centres.

Traditionally the visual impairment of cataract patients before and after surgery has been assessed by monocular visual acuity using a ‘letter chart’, the origins of which date back to the late 19th century11. Although useful, assessing patients’ overall eyesight using visual acuity fails to cover the wide range of problems and functional consequences of visual impairments due to cataract.

Since the 1980s, and in line with a broader WHO definition of disability, the PROM approach has attracted the attention of medical practitioners, researchers and health economists12. This methodology involves the validation of standardized questions exploring patients’ subjective perception of their state of health in relation to particular issues. The obvious theoretical advantage of the PROM approach is that it expands medical insight beyond the traditional narrow perspective of focusing attention on symptoms and signs of diseases13. A PROM may in addition provide data useful for health economic analyses.

A number of questionnaire instruments have been proposed in the ophthalmic and vision science literature, several of which were designed specifically to measure the state of vision of cataract patients2 7 8 14. Most published scales were developed within a Classical Test Theory (CTT) framework15, a traditional psychometric paradigm which is now widely acknowledged to have non-trivial limitations16. These methodological weaknesses can however be overcome by the alternative psychometric approaches of Item Response Theory (IRT)16 including through Rasch modeling17–19. It is the adoption of the stringent criteria of measures normally used in the physical sciences which makes the IRT framework particularly valuable when applied to PROMs20. The Catquest-9SF questionnaire with 9 items was developed using CCT and subsequently reduced and refined using Rasch analysis, the longer precursor instrument having originated in Sweden in 1990s7. This scale has been regarded by many as a ‘best of class’ instrument, attracting favourable commentary6, and prior to Cat PROM5 development was endorsed by the International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement (ICHOM) [http://www.ichom.org/medical-conditions/cataracts/] as their suggested example of a Rasch calibrated PROM.

The more recent Cat-PROM59 has been validated within the Rasch framework and consists of just 5 questions harvested from two existing UK instruments, the VSQ21 and the VCM122. The item reduction and validation process was conducted using data from typical UK patients undergoing cataract surgery, with the final Cat-PROM5 item set demonstrating satisfactory psychometric properties9. Determination of the final item set was influenced by statistical considerations, a patient ‘co-researcher’ advisory group and expert view. As part of the Cat-PROM5 development work, completions of the Catquest-9SF questionnaire were simultaneously obtained from participants, allowing a direct comparison of the performance of both instruments.

Methods

Participants

Analyses presented here are based on a group of 822 patients recruited from 4 cataract surgical centres in England (Bristol, Torbay, Cheltenham, Brighton). Data for the study were collected in 3 separate cycles (Pilot, Cycle 1 and Cycle 2). In order to estimate sensitivity to surgical intervention (effect size), participants in Cycles 1 and 2 were asked to complete questionnaires both before and after their cataract operation.

Analytical strategy

Comparative analysis was conducted by means of separate Rasch calibrations of both questionnaire instruments. In both analyses we used the Partial Credit Model (PCM)19 23 available within the Winsteps analysis program [www.winsteps.com].

Because the study included repeated measurements (before and after surgery) for Cycles 1 and 2 there was an issue with violation of the Rasch analysis assumption of independence of observations. The Rasch analyses were therefore split into two phases, calibration and scaling. In the first (calibration) phase participants who had contributed two questionnaire completions had either their pre- or postoperative completion (never both) randomly selected for inclusion in the analysis set, a procedure which avoided violation of the independence assumption. This set of data was Rasch analyzed and the item parameters (difficulties and Rasch-Andrich thresholds) established. These were then used at the next stage as anchors for estimation of the person parameters for the participant’s alternative (pre- or post-operative) completion. This analytical schedule avoided the problem of case dependency within the data, yet provided person estimates for two time points, thus allowing valid comparisons of the outcomes of pre- and post-operative groups.

Having completed analyses separately for Cat-PROM5 and Catquest-9SF the performance of both scales was compared with regards to three general questions: (1) Do they both measure the same construct? (2) How precise are each of the scales? (3) How well does each function when applied to typical UK NHS cataract patients? The first was assessed in terms of the correlation between the two questionnaires, we assumed a correlation of 0.70 (nearly 50% of common variance) or above would be sufficient. Precision of each was assessed using two reliability indexes: Rasch based reliability (the share of the ‘true’ variance in the total observed variance of the measure) and the classical Cronbach’s alpha with 0.70 to < 0.80 regarded as acceptable, 0.80 to <0.90 as good and 0.90 or above as excellent. To answer the final question we compared performance of both scales on several criteria providing insights on the functioning of each in a UK context. Since Catquest-9SF was developed and validated in other cultural and geographical contexts (Sweden & Australia) it was deemed important to assess these elements on a relevant UK patient group. We assessed these criteria: Rasch-Andrich item thresholds ordered in the expected (increasing) order; item fit (mean square outfit /infit statistics within 0.7-1.3); point-measure item correlation (>=0.4); category averages increasing monotonically along the Rasch continuum; unidimensionality (highest eigenvalue of residual correlation matrix <2.0); item invariance (Differential Item Functioning or DIF, assessed by both significance testing and by differential magnitude following the Educational Testing Service (ETS) classification of |DIF|>0.63 as being large); responsiveness to surgery adopting Cohen’s classification of standardized effect sizes (ES: >0.50 moderate; >0.80 large, i.e. the higher the ES the more responsive is the scale to surgical intervention); and completion burden (number of items).

A qualitative study on a separate group of patients explored the face-validity and acceptability of each questionnaire (in terms of language, accuracy, and relevance), particularly for those with visual comorbidities. A purposeful sampling strategy was used to include perspectives from a range of visual comorbidities. Participants included men and women of varying ages as well as pre- or post-operative status. Semi-structured face to face interviews were guided by a topic guide to ensure that discussions covered the same basic issues, but with sufficient flexibility to allow emergence of new issues of importance, and with new points added as analysis progressed to enable exploration of emerging themes and encourage more detailed responses. Where uncertainties arose, respondents were asked how they understood the items and encouraged to explain their reasoning and reflect on their overall perceptions of the questionnaire. Data were analysed using techniques of constant comparison derived from grounded theory methodology24, and emerging themes and codes within transcripts and across the dataset were then compared to look for shared or disparate views among participants. Data collection and analysis continued until the point of data saturation.

Results

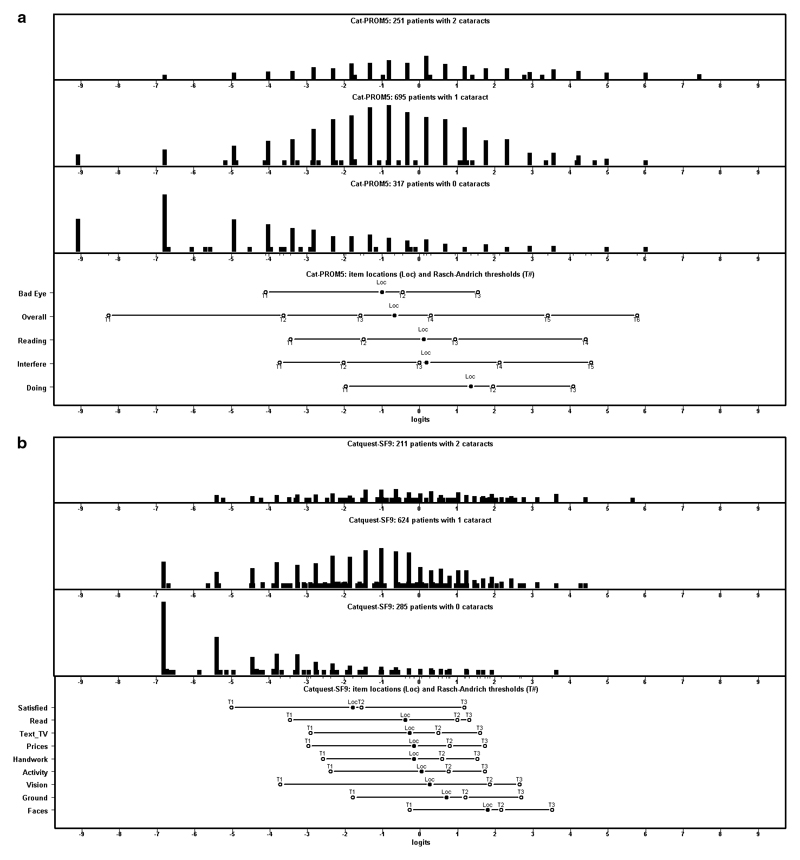

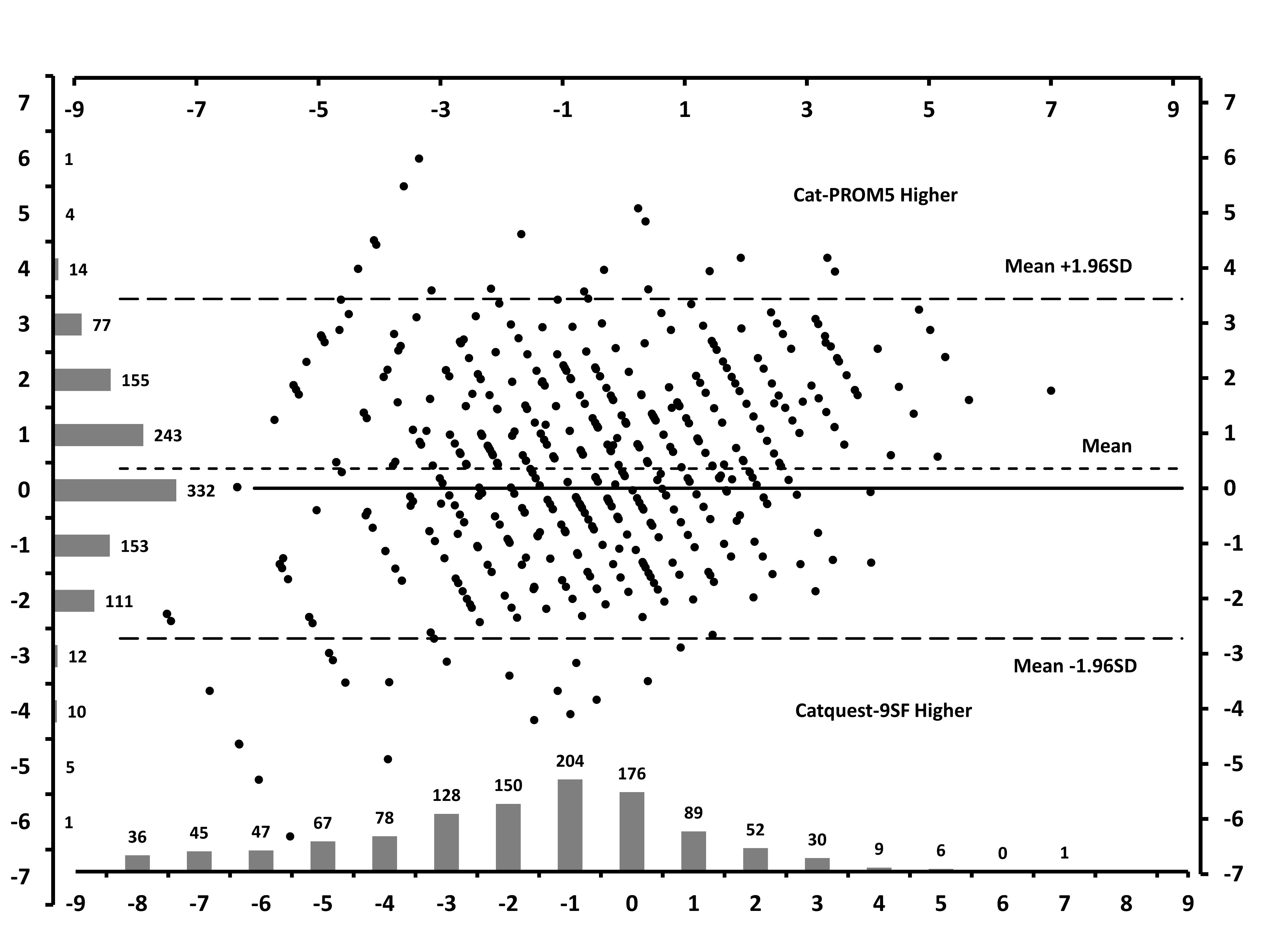

Socio-demographic characteristics for participants have previously been reported9. Briefly, participants mean age was 76 years, 58% were female and 67% were undergoing surgery in their first eye. The respondents’ results (Rasch measure) on both scales showed a strongly positive association with a linear correlation of R=0.85 (P<0.001; N=1,189 completions), Figure 1 presents a Bland-Altman plot of agreement incorporating the distribution of the means along the horizontal axis and the distribution of the differences along the vertical axis. Table 1 provides details of the performance of both questionnaires, and Table 2 summarizes comparative performance based on the parameters noted above.

Figure 1.

Bland and Altman plot of agreement between Cat-PROM5 and Catquest-9SF measures for pre- and post-operative questionnaire completions (mean difference 0.36 logits; N=1,189)

Table 1.

Quality of the measurement models of Cat-PROM5 and Catquest-9SF across all cycles combined.

| Item |

Rasch measure

– item difficulty (SE) |

Infit MnSQ | Outfit MnSQ |

Point measure

correlation |

Rasch-Andrich thresholds

(centralized to item difficulty) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cat-PROM5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||||

|

| ||||||||||

| VSQ_Bad_Eye | -0.89 (.09) | 1.12 | 1.11 | 0.80 | -3.11 | 0.46 | 2.65 | - | - | - |

| Interfere | -0.06 (.08) | 0.73 | 0.76 | 0.89 | -4.17 | -2.29 | -0.16 | 2.39 | 4.23 | - |

| VSQ_Overall | -0.51 (.08) | 1.02 | 1.01 | 0.88 | -7.70 | -3.02 | -0.84 | 1.14 | 3.88 | 6.55 |

| VSQ_Doing | 1.41 (.11) | 0.91 | 0.87 | 0.77 | -3.56 | 0.72 | 2.85 | - | - | - |

| VSQ_Reading | 0.05 (.08) | 1.18 | 1.14 | 0.82 | -3.53 | -1.70 | 1.09 | 4.14 | - | - |

|

| ||||||||||

| Catquest-9SF | 1 | 2 | 3 | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Cat_Vision | 0.26 (.09) | 0.92 | 0.83 | 0.78 | -3.98 | 1.60 | 2.38 | |||

| Cat_Satisfied | -1.80 (.08) | 1.32 | 1.32 | 0.78 | -3.22 | 0.24 | 2.98 | |||

| Cat_Read | -0.39 (.08) | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.79 | -3.08 | 1.38 | 1.70 | |||

| Cat_Faces | 1.80 (.09) | 1.19 | 1.10 | 0.62 | -2.08 | 0.36 | 1.71 | |||

| Cat_Prices | -0.16 (.07) | 0.93 | 0.98 | 0.79 | -2.82 | 0.94 | 1.88 | |||

| Cat_Ground | 0.70 (.08) | 1.10 | 1.25 | 0.71 | -2.49 | 0.50 | 1.99 | |||

| Cat_Handwork | -0.16 (.07) | 0.80 | 0.76 | 0.81 | -2.43 | 0.75 | 1.68 | |||

| Cat_Text_TV | -0.28 (.07) | 0.98 | 1.03 | 0.79 | -2.64 | 0.76 | 1.88 | |||

| Cat_Activity | 0.03 (.07) | 0.75 | 0.66 | 0.81 | -2.42 | 0.73 | 1.69 | |||

Table 2.

Summary of quality of both measures

| Statistics | Cat-PROM5 | Catquest-9SF |

|---|---|---|

| Person reliability index | 0.90 | 0.88 |

| Cronbach’s α | 0.89 | 0.92 |

| Variance explained | 72% | 64% |

| Variance explained by patients | 55% | 48% |

| Variance explained by items | 16% | 16% |

| Variance unexplained | 28% | 36% |

| Highest residual eigenvalue | 1.5 | 1.6 |

| Number of items | 5 | 9 |

| Number of misfitting items (Infit/Outfit out of range 0.7-1.3) | 0 | 2 |

| Number of reversed thresholds | 0 | 0 |

| Number of reversed category means | 0 | 0 |

| Number of statistically significant DIF instances | 3 (7.5%) | 3 (4.2%) |

| Number of instances of ‘large’ DIF i.e. |DIF|≥0.64 Logits * | 1 (2.5%) | 2 (2.8%) |

| Cohen’s standardized effect size (Pilot/Cycle1/Cycle2) ** | -1.45 | -1.47 |

| Cohen’s standardized effect size (Pilot/Cycle1/Cycle2) *** | -1.09 | -1.14 |

Educational Testing Service criteria http://www.ets.org/Media/Research/pdf/RR-12-08.pdf)

denominator as SD from pre-op time point

denominator as SD for the whole sample (including both pre-and post-operatively)

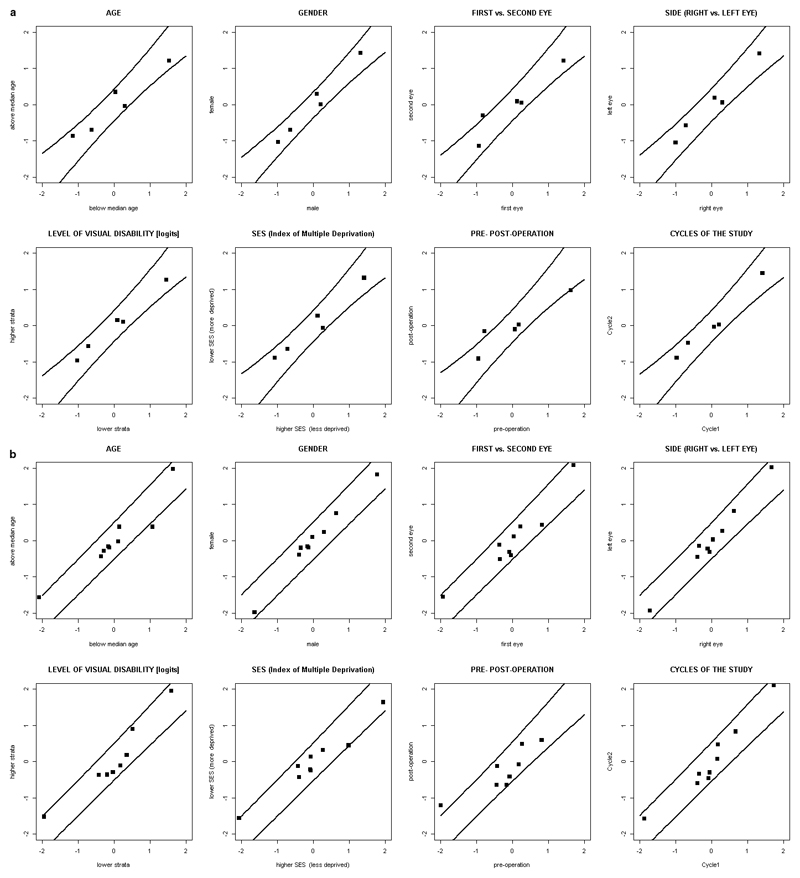

From both tables it is apparent that each scale performs well with only moderate to small relative differences. Figure 2 provides ‘Person-Item’ or ‘Wright’s maps’ for both scales illustrating the positions for each item and each of their levels. Pre-operatively there were no ceiling or floor effects for either scale. Post-operatively there was a moderate floor effect for Cat-PROM5 with 9% of respondents reporting no problems and for Catquest-9SF a more obvious floor effect with 25% reporting no problems. Figure 3 depicts the Differential Item Functioning (DIF) plots for each scale for assessment of item invariance across 8 groupings of participants (e.g. older vs. younger), showing that with very few exceptions the performance of the individual items is invariant across these groupings.

Figure 2.

Person-Item or Wright’s maps illustrating the distributions of patient responses in the upper panel from those with 2 cataracts, in the second panel from those with 1 cataract (a cataract in one eye and either pseudophakia or a clear crystalline lenses in the other), and in the third panel those with no cataracts (either bilateral pseudophakia or pseudophakia in one eye and a clear crystalline lenses in the other). The lower panel in Figure 2a shows the positions of the Item Locations (Loc) and Category Thresholds (T#) for Cat-PROM5 and Figure 2b shows these similarly for Catquest-9SF. All panels refer to the same horizontal scale from -9 to +9 logits.

Figure 3.

Differential Item Functioning graphics for partitioning of response data across 8 groupings for Cat-PROM5 (3a) and Catquest-9SF (3b). The graphics illustrate that item functioning is largely invariant across these groupings.

In the qualitative study sixteen interviews were conducted with nine men and seven women with a mean age of 75 years (range 57-92). Eleven patients were awaiting their cataract surgery, and five had recently undergone surgery. Thirteen participants had other visual co-morbidities, including age related macular degeneration (wet and dry), myopic macular degeneration, amblyopia, glaucoma, retinal vascular occlusion, previous retinal detachment, Fuchs endothelial dystrophy, and neurological visual field loss. Interviews lasted an average of 50 minutes (range = 24-73). Overall both questionnaires were well received, although patients with severe visual co-morbidities commented that it was difficult to differentiate between how the cataract and other conditions affected their quality of life. Most participants preferred the large-font format of Cat-PROM5. Some preferred questions with more response options as in Cat-PROM5, and others fewer response options as in Catquest 9SF. The specific scenarios of Catquest-9SF created some uncertainty where other health problems affected the issue being addressed, and where the issue was not relevant to their lives respondents were uncertain about how to respond. In contrast, Cat-PROM5 enabled them to determine the individual vision related factors which they perceived to be important, and to respond to the questions easily.

Discussion

The strong linear correlation (R=0.85) between the scales provides empirical evidence that both scales are measuring the same theoretical concept. The Bland Altman plot with distributions illustrates good agreement between individual person measures derived separately from the two questionnaires. Each has a similar high level of precision, Cat-PROM5, achieves ‘excellent’ reliability based on the Rasch model while Catquest-9SF achieves this level on the classical Cronbach’s alpha. It should be noted however that this latter coefficient is in part dependent on the number of questions included in the scale and Catquest-9SF has almost twice as many questions as Cat-PROM5. In the context of a scale intended for use in high volume cataract surgical services a longer scale has potential logistical and cost disadvantages which need to be born in mind. From these results however it is clear that both scales display high precision with the shorter Cat PROM5 perhaps having an edge over the longer Catquest-9SF. Both scales fit the data well with fitting indices mostly within acceptable limits, no reversed thresholds and point-measure correlations positive and reasonably high. Both scales are unidimensional constructs with the highest eigenvalues in each case below 2.0 (CatPROM5 1.5, Catquest-9SF 1.6). Had an alternative more stringent criterion of a highest eigenvalue threshold of 1.5 or less been used7 25, unidimensionality would however have been borderline.

Person-Item or Wright’s maps for both scales (Figure 2) illustrate good span and targeting, with both scales performing similarly with a slightly wider (better) range observed for Cat PROM5. There were no ceiling effects for either scale although a notable post-operative floor effect (25%) was evident for Catquest-9SF. It should be borne in mind that following successful cataract surgery in both eyes vision would be expected to have been restored to normal or near normal in the absence of visually significant comorbidities. Cat-PROM5 would however be more sensitive to detection of relatively minor post-operative residual visual difficulties. Both scales were highly responsive to surgical intervention, the estimated effect sizes or Cohen’s delta for each being very large, marginally greater for Catquest-9SF. Based on the theoretically more relevant pre-op SD calculation these were both near -1.5SD and based on the alternative pooled sample SD near 1.1SD (both calculation methods have been provided here for purposes of comparison with other published results). It is worth noting that an effect size of >0.8SD is regarded as a ‘large’ effect.

Item performance was mostly invariant for both measures across a range of groupings. In Table 2 and Figure 3 the number of statistically significant violations of invariance measured by DIF was 3 for both Catquest-9SF and Cat-PROM5. Of these, 2 were deemed ‘large’ for Catquest-9SF and 1 for Cat-PROM5. A statistically significant and large DIF thus occurred in less than 5% of all comparisons for each instrument.

The qualitative study indicated that both questionnaires were well received. Participants varied in regard to ease of completion of fewer (Catquest-9SF) or more (Cat PROM5) item response options. On the whole, patients preferred that the Cat-PROM5 questionnaire enabled them to determine the individual vision related factors which they perceived to be important, and to respond to the questions accordingly. In contrast the specific scenarios of Catquest-9SF provided particular instances that were sometimes not relevant to patients’ lives, and there was little opportunity to capture the ways in which cataract did affect their lives beyond those specific scenarios. The questions in Cat-PROM5 have previously been shown to have high face-validity for the majority of cataract patients,21 affirmed by the qualitative element of work.

Conclusion

In this report Cat-PROM5 was compared against the English translation of Catquest 9SF, a widely used originally Swedish cataract PROM instrument. These results show that both scales measure the same concept with high precision, are unidimensional, conform to the stringent Item Response Theory requirements of the Rasch model, and are highly responsive to cataract surgical intervention with very large effect sizes of around 1.5SD (baseline SD). The less restrictive Cat-PROM5 questions were preferred by patients, and at almost half the length this would seem the more feasible implementation option for measurement of visual difficulty related to cataract and its relief from surgery in high volume surgical services such as those of the UK NHS.

Summary Box.

What was known before:

The ‘patient’s view’ is increasingly recognized as a key measure in health service delivery

Patient’s self-reported visual difficulty related to cataract can be reliably measured using questionnaire instruments which must be brief to be implementable in high volume services

Cat-PROM5 and Catquest-9SF both demonstrate good psychometric performance with high responsiveness to surgery

What this study adds:

A head-to-head comparison between the best two candidate instruments demonstrates that both perform equally well psychometrically

Patients preferred Cat-PROM5 in terms of it being almost half the length of Catquest 9SF and less proscriptive, allowing them to map their own visual difficulties to the questions

Acknowledgements

This paper presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under its Programme Grants for Applied Research Programme (Reference Number RP-PG-0611-20013). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

JLD was supported by the NIHR Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC) West at University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust, and is an NIHR Senior Investigator.

It is with deep regret that we note the death of our co-author, friend and colleague Robert Johnston, who sadly died in September 2016.

Funding Statement:

This work was supported by National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) grant number RP-PG-0611-20013.

Footnotes

Competing Interests Statement:

Authors have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Frost NA, Hopper C, Frankel S, Peters TJ, Durant JS, Sparrow JM. The population requirement for cataract extraction: a cross-sectional study. Eye (Lond) 2001;15(Pt 6):745–52. doi: 10.1038/eye.2001.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McAlinden C, Gothwal VK, Khadka J, Wright TA, Lamoureux EL, Pesudovs K. A head-to-head comparison of 16 cataract surgery outcome questionnaires. Ophthalmology. 2011;118(12):2374–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DH. Hospital Episode Statistics for England. HSCIC. Hospital admitted patient care activity, 2015-16: Procedures and interventions - 4 character. [Accessed 31 May 2017]; http://content.digital.nhs.uk/article/2021/Website-Search?productid=23488&q=cataract&sort=Relevance&size=10&page=1&area=both#top.

- 4.Royal National Institute of Blind People (RNIB) Saving Money, Losing Sight. London, UK: 2013. [accessed 31 May 2017]. https://www.rnib.org.uk/sites/default/files/Saving%20money%20losing%20sight%20Campaign%20report_0.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Foot B, MacEwen C. Surveillance of sight loss due to delay in ophthalmic treatment or review: frequency, cause and outcome. Eye (Lond) 2017;31(5):771–75. doi: 10.1038/eye.2017.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coronini-Cronberg S. The cataract surgery access debate: why variation may be a good thing. Eye (Lond) 2016;30(3):331–2. doi: 10.1038/eye.2015.272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lundstrom M, Pesudovs K. Catquest-9SF patient outcomes questionnaire: nine-item short-form Rasch-scaled revision of the Catquest questionnaire. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2009;35(3):504–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2008.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lundstrom M, Pesudovs K. Questionnaires for measuring cataract surgery outcomes. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2011;37(5):945–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2011.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sparrow JM, Grzeda MT, Frost NA, Johnston RL, Liu CSC, Edwards L, et al. Cat-PROM5: A brief psychometrically robust self-report questionnaire instrument for cataract surgery. Eye. 2017 doi: 10.1038/eye.2018.1. (In Press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gothwal VK, Wright TA, Lamoureux EL, Lundstrom M, Pesudovs K. Catquest questionnaire: re-validation in an Australian cataract population. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2009;37(8):785–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2009.02133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Massof RW. The measurement of vision disability. Optom Vis Sci. 2002;79(8):516–52. doi: 10.1097/00006324-200208000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dawson J, Doll H, Fitzpatrick R, Jenkinson C, Carr AJ. The routine use of patient reported outcome measures in healthcare settings. BMJ. 2010;340:c186. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pesudovs K, Burr JM, Harley C, Elliott DB. The development, assessment, and selection of questionnaires. Optom Vis Sci. 2007;84(8):663–74. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e318141fe75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kowalski JW, Rentz AM, Walt JG, Lloyd A, Lee J, Young TA, et al. Rasch analysis in the development of a simplified version of the National Eye Institute Visual-Function Questionnaire-25 for utility estimation. Qual Life Res. 2012;21(2):323–34. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-9938-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spearman C. The proof and measurement of association between two things. By C. Spearman, 1904. Am J Psychol. 1987;100(3–4):441–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Embretson SE, Reise SP. Item Response Theory for Psychologists Multivariate. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andrich D. Rasch Models for Measurement. SAGE Publications, Inc; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rasch G. Probabilistic models for some intelligence and attainment tests. Copenhagen: The Danish Institute of Education Research; 1960. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wright BD, Stone MH. Best Test Design. Rasch Measurement. Chicago: MESA; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 20.van der Linden W. Fundamental Measurement and the Fundamentals of Rasch Measurement. In: Wilson M, editor. Objective measurement: theory into practice, the American educational research association. Chicago: Ablex; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Donovan JL, Brookes ST, Laidlaw DA, Hopper CD, Sparrow JM, Peters TJ. The development and validation of a questionnaire to assess visual symptoms/dysfunction and impact on quality of life in cataract patients: the Visual Symptoms and Quality of life (VSQ) Questionnaire. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2003;10(1):49–65. doi: 10.1076/opep.10.1.49.13775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frost NA, Sparrow JM, Durant JS, Donovan JL, Peters TJ, Brookes ST. Development of a questionnaire for measurement of vision-related quality of life. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 1998;5(4):185–210. doi: 10.1076/opep.5.4.185.4191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bond TG, Fox CM. Applying the Rasch Model: Fundamental Measurement in the Human Sciences. Third Edition. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Strauss A, Corbin J. Grounded theory methodology. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. Handbook of Qualitative Research. London: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith RM, Miao CY. Assessing unidimensionality for Rasch measurement. In: Wilson M, editor. Objective Measurement: Theory into Practice. Norwood, NJ: Ablex; 1994. pp. 316–28. [Google Scholar]