Abstract

This article describes the protocol for the Systematic Multi-domain Alzheimer’s Risk Reduction Trial (SMARRT), a single-blind randomized pilot trial to test a personalized, pragmatic, multi-domain Alzheimer’s disease (AD) risk reduction intervention in a US integrated healthcare delivery system. Study participants will be 200 higher-risk older adults (age 70–89 years with subjective cognitive complaints, low normal performance on cognitive screen and ≥ two modifiable risk factors targeted by our intervention) who will be recruited from selected primary care clinics of Kaiser Permanente Washington (KPWA), oversampling people with non-white race or Hispanic ethnicity. Study participants will be randomly assigned to a two-year Alzheimer’s risk reduction intervention (SMARRT) or a Health Education (HE) control. Randomization will be stratified by clinic, race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white vs. non-white or Hispanic) and age (70–79, 80–89). Participants randomized to the SMARRT group will work with a behavioral coach and nurse to develop a personalized plan related to their risk factors (poorly controlled hypertension, diabetes with evidence of hyper or hypoglycemia, depressive symptoms, poor sleep quality, contraindicated medications, physical inactivity, low cognitive stimulation, social isolation, poor diet, smoking). Participants in the HE control group will be mailed general health education information about these risk factors for AD. The primary outcome is two-year cognitive change on a cognitive test composite score. Secondary outcomes include: a) improvement in targeted risk factors, b) individual cognitive domain composite scores, c) physical performance, d) functional ability, e) quality of life, and f) incidence of mild cognitive impairment (MCI), AD and dementia. Primary and secondary outcomes will be assessed in both groups at baseline and 6, 12, 18 and 24 months.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, dementia, risk reduction behavior, health promotion, delivery of health care, integrated

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) prevalence is growing, creating a critical need for prevention. The number of people worldwide living with AD and related dementias is expected to rise from 47 million in 2015 to 132 million by 2050 [1]. Current medications do not change the disease course [2], and several drugs have recently failed Phase III trials [3–10]; thus, there is growing interest in strategies to prevent AD [11, 12]. We have estimated that up to 30% of AD may be attributable to modifiable risk factors including physical inactivity, low education, smoking, diabetes, hypertension, depression, and obesity [13, 14]. Our estimates are now being supported by several large population-based cohort studies, which are finding that in some populations AD prevalence is decreasing in parallel with population-level changes in risk factors, such as better education, lower smoking and better control of cardiovascular risk factors [15–21]. In addition, multi-domain prevention trials in Europe and Asia have found that interventions targeting multiple risk factors simultaneously in older adults can slow cognitive decline and reduce cognitive impairment [22–24], although results have been mixed [25–27]. These studies raise hope that multi-domain risk reduction interventions in higher-risk older adults have the potential to delay the onset of AD; however, additional studies are needed to clarify the effects of different intervention approaches in different study populations.

To date, there has not been a multi-domain Alzheimer’s risk reduction trial in the US. In addition, multi-domain risk reduction trials to date have typically involved relatively intensive interventions that would be difficult to implement in real-world settings. The Systematic Multi-domain Alzheimer’s Risk Reduction Trial (SMARRT) is a single-blind randomized pilot trial to test a personalized, pragmatic, multi-domain AD risk reduction intervention in a US integrated healthcare delivery system. The purpose of the pilot trial is to lay the foundation for a future multisite trial by developing and testing procedures and demonstrating proof-of-concept. This manuscript describes the study protocol for SMARRT.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Objectives

Primary Objective

The primary objective of this pilot trial is to collect preliminary data on SMARRT compared to Health Education (HE) control. This will provide us with proof-of-concept data for our primary outcome of two-year cognitive change and will enable us to estimate effect sizes for a larger multi-site trial. In addition, it will enable us to assess feasibility and acceptability and to determine whether intervention refinements are needed.

Secondary Objectives

Our secondary objectives are to compare changes in Alzheimer’s risk factors over two years in those randomized to SMARRT vs HE. The results will determine if SMARRT can have a meaningful impact on cognition by demonstrating significantly greater risk factor change than HE.

In addition, we will gather preliminary data on the impact of SMARRT vs HE on cognitive domain scores, physical performance, functional ability, quality of life and incidence of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and AD.

Overview of Study Design

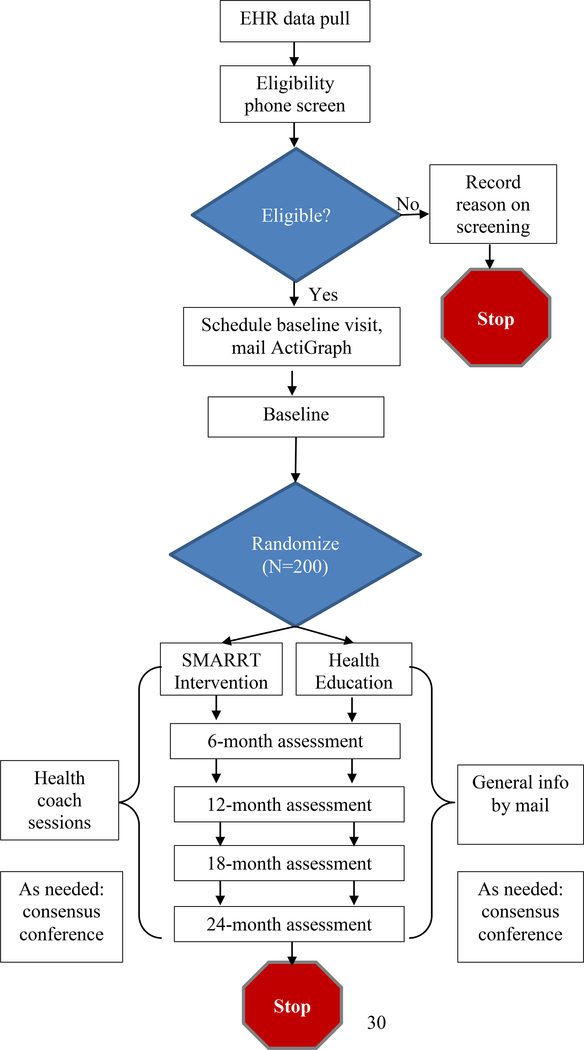

This study involves a pragmatic, single-blind, randomized controlled pilot trial. We will randomize 200 higher-risk older adults to the two-year SMARRT intervention or HE control. For the intervention, the team will work with participants to develop a tailored action plan to address risk reduction. Targeted areas will include: increasing physical, mental and social activities; optimally controlling cardiovascular risk factors (hypertension, diabetes), including avoiding both hyper and hypoglycemia among people with diabetes; quitting smoking; reducing depressive symptoms; improving sleep; neuroprotective diet; and decreasing use of potentially harmful medications. The HE group will received general information about these AD risk factors. Primary and secondary outcomes will be assessed in both groups at baseline and 6, 12, 18 and 24 months. The study flow diagram is provided in Figure 1, and an overview of study procedures is provided in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Systematic Multi-domain Alzheimer’s Risk Reduction Trial (SMARRT) Study Flow

Table 1.

Overview of Study Procedures

| Procedure | Screening | Baseline | Health Coach Sessions (SMARRT Group Only) | Health Education (HE Control Only) | 6 Month Assessment | 12 Month Assessment | 18 Month Assessment | 24 Month Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria | X | |||||||

| Informed Consent Form | X | X (1st session) | ||||||

| Actigraph | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Physical Function Tests | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Blood Pressure and Height/Weight | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Questionnaire packet | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Neuropsychological Test Battery | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Meet with Interventionist | X | |||||||

| Mailed Education Forms | X | |||||||

| Adverse Events | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

Setting

Kaiser Permanente Washington (KPWA) is an integrated healthcare delivery system with about 710,000 members in the Northwest United States that provides members with both insurance coverage and healthcare. Because KPWA provides insurance coverage, we have complete information about members’ healthcare utilization as well as diagnosis and procedure codes and medication fills. About 2/3rds of KPWA members receive all or nearly all clinical care from KPWA physicians at KPWA-owned clinics. For those members we also have information on clinical measures such as vital signs (e.g. blood pressure values) and laboratory test results. This study will only recruit members who are receiving their clinical care within KPWA’s healthcare system. The University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) will provide study oversight.

Regulatory Review and Approval

All study procedures have been reviewed and approved by Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) at KPWA and UCSF, and the study will be registered on ClinicalTrials.gov. All study participants will provide written, informed consent before participating in assessments or intervention activities. We received a consent and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) waiver to use electronic health records (EHR) to identify and recruit potential participants. HIPAA is a national privacy regulation in the US that requires all research study participants to review and sign a form that describes what type of information is being collected and how it will be used prior to participating in a study. IRBs can provide researchers with permission to use patient data for research without their prior approval when certain conditions are met, such as the research involves no more than minimal risk and is of sufficient importance to outweigh intrusion into the privacy of research subjects. Consistent with federal and state laws, all KPWA patients are provided with a Notice of Privacy Practices stating that their information may be used for research. Patients who have previously requested not to be contacted or have their records reviewed for research studies will be excluded.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion Criteria

Participants must meet all the inclusion criteria to participate in this study. These are: age 70–89 years (to target a population at increased risk of experiencing cognitive decline that is still able to participate fully in a two-year intervention study); English language fluency; cognitive concern (self-reported decline in memory or thinking over past 2 years); low normal performance on a brief telephone cognitive screen (short Cognitive Abilities Screening Instruments [CASI] [28]); and at least two additional risk factors that will be targeted by our intervention (Table 2). Low normal CASI scores will be defined as 26 to 29 inclusive. This reflects scores lower than the median score of participants enrolled in the Adult Changes in Thought (ACT) [29] Study (median 30, range 6 to 33) while excluding those whose scores suggest possible dementia (score ≤ 25) [28, 30]. A novel feature of this study is that for recruitment, we will identify many of these risk factors using EHR data. We will use the EHR data to target recruitment to people with at least one risk factor of interest, which should improve efficiency of recruitment. For most of these risk factors, we will confirm them during telephone screening, and these data will be used to determine final study eligibility.

Table 2.

Inclusion criteria for SMARRT Trial

| Inclusion Criteria | Definition | Data source |

|---|---|---|

| Older age | 70–89 years | EHR |

| Language | Fluent in English | EHR and telephone screening |

| KPWA enrollment status | ≥ 12 months (allow 3-month gap) | EHR |

| Low-normal cognitive performance | Brief CASI[28] score 26 to 29 inclusive | Telephone screening |

| Subjective cognitive complaints | Self-report of concern with memory or thinking, as captured by replying yes to the question: “In the past two years, have you experienced a decline in your memory or thinking?” | Telephone screening |

| ≥2 targeted risk factors* | ||

| • Poorly controlled hypertension | Systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 twice in the past 6 months | EHR |

| • Poorly controlled diabetes, with evidence of either hyperglycemia or potential hypoglycemia |

Hyperglycemia: ≥

1 hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) ≥ 8.0 in past 12 months

Potential hypoglycemia: Diabetes, taking insulin (at least one fill in past 6 months) and one or more of the following: 1) most recent HbA1c in past 12 months ≤ 6.0; 2) diagnosis code for hypoglycemia in past 1 year |

EHR |

| • High depressive symptoms |

Initial recruitment:

Score ≥3 on Patient Health Questionaire-2 (PHQ-2)[50] screen in past 12

months Final eligibility: Score ≥10 on PHQ-8[51] |

EHR (recruitment) Telephone screening (final eligibility) |

| • Poor sleep |

Initial recruitment:

diagnosis code for sleep disorder and/or ≥2 fills for a sleep

medication in the past 12 months Final eligibility: Scoring above the cut-off on the sleep questionnaire (problems with sleep 3+ nights/week and bothered “somewhat” or more) |

EHR (recruitment) Telephone screening (final eligibility) |

| • Risky medications | ≥ 2 fills for medications in a given class of risky medications in the past 6 months, per modified Beers criteria.[48] | EHR |

| • Physical inactivity | < 30 minutes moderate intensity most days (<150 minutes/week, Surgeon General guidelines) | Telephone screening |

| • Social isolation | Rarely or never get social and emotional support needed (scoring ≥ 6 out of 9 possible points)[36] | Telephone screening |

| • Current smoking |

Recruitment: EHR

evidence of current use of any tobacco Final eligibility: self-reported current smoking on telephone screen |

EHR (recruitment) Telephone screening (final eligibility) |

Exclusion Criteria

Candidates meeting any of the exclusion criteria during EHR review or telephone screening will be excluded from study participation. For initial determination of eligibility, we will rely on information recorded in the EHR, such as International Classification of Diseases 10 (ICD-10) diagnosis codes and medication fills. We will exclude those who are currently residing in a skilled nursing or rehabilitation facility; received palliative care or hospice services (based on clinic encounters, past 2 years); Charlson comorbidity index score > 5 (based on ICD-10 diagnoses, past year, to exclude severe comorbidity likely to interfere with ability to participate in the study) [31]; bipolar illness or schizophrenia (any ICD-10 code, past 2 years, or receiving two or more fills for antipsychotic medications, past 6 months); current alcohol or drug use disorder (any ICD-10 code, past 2 years); receiving chronic opioid therapy (enough supplied to have taken 20 morphine equivalent doses/day for ≥70 days in the previous 90-day period); Parkinson’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or multiple sclerosis (any ICD-10, past 2 years); severe visual impairment (any ICD-10, past 2 years, which could limit ability to participate in the intervention and outcomes assessments); requested not to be contacted or not to have their medical record reviewed for research studies (KPWA Health Research Institute database); and evidence of dementia (ICD-10 codes, past 2 years, or prescription fills for dementia medications such as donepezil or memantine, past 2 years). The use of EHR data to identify exclusion criteria also is a novel feature that is designed to improve efficiency of recruitment. Additional exclusion criteria will be assessed during telephone screening and will include: severe hearing impairment (unable to complete telephone screen); inability to come in for assessments; inability to participate in an intervention and outcomes assessments conducted in English; plans to disenroll from KPWA or move out of the area in the next 2 years; current enrollment in the Adult Changes in Thought (ACT) study; answering ‘yes’ to the question “have memory problems contributed to a decline in your ability to care for yourself over the past year;” answering ‘no’ to the question “has your memory or thinking declined in the past 2 years;” short CASI scores ≤25 (suggestive of cognitive impairment) or ≥30 (low likelihood of experiencing cognitive decline over 2 years); or inability to provide informed consent.

Enrollment and Assessment Procedures

Recruitment

Our goal is to target higher-risk individuals who will be motivated to make medical and behavioral changes to reduce their Alzheimer’s risk. Initial eligibility will be determined using medical risk data from the EHR. Final eligibility will be determined during telephone screening.

Initial eligibility criteria using EHR data will be based on having at least one targeted risk factor. We will recruit among those with at least one targeted risk factor (rather than two) because not all risk factors of interest can be identified from the EHR (e.g., physical activity), and we expect many individuals initially identified as having one risk factor will ultimately have two or more based on information collected on the telephone interview. The final inclusion criteria of at least two risk factors will be determined via a combination of EHR data (for hypertension, diabetes and contraindicated medications) and phone screening (for the remaining risk factors). In order to achieve greater diversity, we will use race-ethnicity information from KPWA demographic files to oversample potential participants who are Hispanic or non-white, with a goal of having at least 30% of study participants from diverse backgrounds.

Recruitment letters describing the study will be mailed to current KPWA members who meet initial eligibility criteria. These letters will include a phone number that participants can call to opt out of being contacted for this study.

Telephone Screening Evaluation

Approximately one week after letters have been mailed, interviewers will call potentially eligible people and describe the study activities, randomization, and risks and benefits of the study. They will confirm understanding, invite questions and obtain verbal informed consent to continue with the screening process. Final eligibility will be determined using a standardized screening questionnaire.

Because our goal is to enroll people with low normal cognitive function, we will also perform the short telephone version of the CASI [28]. Enrollment will be restricted to those whose scores fall between 26 and 29 inclusive (see inclusion criteria section for rationale). Individuals who are eligible and interested will then be scheduled for in-person written consent and baseline assessment, and will be sent an accelerometer by mail to obtain a measure of baseline levels of physical activity.

Consenting Procedure

At the written consent and baseline assessment visit, the assessor will discuss the nature of the study and review the consent and HIPAA authorization form. All study participants will provide written informed consent.

Baseline Assessments

All participants will complete the assessments listed below at baseline and four follow-up visits spaced over 24 months (approximately 6, 12, 18 and 24 months).

Primary Outcome: Two-year Cognitive Change (Composite Score):

Cognitive function will be measured by a global composite score from the modified Neuropsychological Test Battery (mNTB) [23, 32], a comprehensive battery including tests of memory (Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised [WMS-R] Visual Paired Associates, WMS-R Logical Memory, Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease [CERAD] Word List); attention (WMS-R Digit Span); executive functioning/processing speed (Trail Making Test, Stroop Test, Digit Symbol Substitution Test); and language (Category Fluency Test, Phonemic Fluency [FAS]). The original NTB [33], on which the mNTB builds, is well-validated with strong test-retest reliability [33, 34], ability to distinguish between individuals at different clinical stages (i.e., normal cognition, MCI, AD) [34], and sensitivity to detecting cognitive change in early stages of Alzheimer’s [33]. The mNTB [23, 32] improves on the original NTB by adding measures of executive functioning and processing speed, domains that are important to assess in prevention trials as these abilities are compromised by important AD risk factors such as cardiovascular disease and physical inactivity. Importantly, the mNTB was found to be sensitive to change in prior multi-domain AD risk reduction trials [23, 24].

Secondary Outcomes.

- Improvement on Alzheimer’s risk factors. Because this is a pilot study, one of our goals is to quantify the number and type of Alzheimer’s risk factors each person has at baseline as well as change in each risk factor over two years in response to the SMARRT intervention. This will be accomplished using a combination of validated objective and self-report measures as well as EHR data. We chose to use individual measures rather than an AD risk score so that we could examine each risk factor independently. In addition, current AD risk scores do not include all of the risk factors being targeted in this study. Specific measures include:

- Self-reported physical activity (Rapid Assessment of Physical Activity for Older Adults, RAPA) [35]: a 9-item physical activity inventory with yes/no responses, designed for older adults and based on U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention physical activity recommendations.

- Objectively measured physical activity (waist-worn ActiGraph accelerometer): worn for 7 days prior to each assessment visit with counts per minute aggregated using ActiLife software.

- Leisure / Social Activity (PROMIS Satisfaction with Participation in Discretionary Social Activities, Short Form) [36]: 7-item questionnaire that asks individuals to rate satisfaction with engagement in social and other leisure activities and social connectedness in the past 7 days on a 5-point Likert scale (not at all … very much).

- Cognitive activity (Cognitive Activity Questionnaire) [37]: 11-item questionnaire that asks how often individuals engage in cognitively stimulating activities such as reading the newspaper or computer activities on a 6-point Likert scale (once a month/never … every day).

- Control of cardiovascular risk factors (hypertension and diabetes): blood pressure and Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) values from EHR; height, weight, and blood pressure measured at each assessment visit.

- Smoking: self-reported current tobacco usage assessed by asking “Have you smoked even a puff in the last 7 days?” and if yes, “How many cigarettes have you smoked in the last 7 days?”

- Depressive symptoms (Center for Epidemiologic Studies – Depression Scale, CES-D) [40]: 20-item questionnaire that assesses both positive and negative affect over the last week rated on a scale from 0 (rarely or none of the time) to 4 (most or all of the time).

- Sleep quality (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, PSQI) [41]: 19-item questionnaire that assesses sleep quality and disturbances over the past month (not at all, less than once a week, once or twice a week, three or more times a week).

- Potentially harmful medications (identified from KPWA pharmacy database): based on a detailed list of contraindicated medications developed for the intervention (see Intervention section below).

Individual cognitive domain scores

Physical performance (Short Physical Performance Battery, SPPB) [42]: Includes standard tests of balance, time to complete five chair stands, and usual gait speed.

Functional ability (Cognitive Function Instrument, CFI) [43]: 14-item self-report inventory of cognitive and functional difficulties in everyday tasks (e.g., remembering appointments, managing finances, driving).

Quality of life (PROMIS Global Health) [44]: 10-item questionnaire includes items on self-rated health (physical, mental, social) as well as pain and fatigue.

Incidence of MCI, dementia and AD (determined based on decline in cognitive status through consensus conferences using standard clinical criteria) [45–47].

Randomization and Blinding

After the baseline visit, study participants will be randomized in a 1:1 ratio to intervention and control groups. Randomization will be implemented using randomly permuted blocks of size two, stratified on clinic, age (70–79 vs. 80–89), and race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white vs. non-white or other Hispanic) This will maximize blinding of outcome assessors by ensuring that the sequence is not easy to guess and will achieve balanced groups that accurately reflect the underlying composition of the study population. The randomization sequences will be generated in advance by the study statistician, securely stored electronically, and accessible only to intervention staff. Research staff who enroll study participants and collect outcome data will be unaware of the randomization sequence and will be blinded to group assignment.

Follow-up and Final Visits

Assessments given at baseline will be repeated four times over the following 24 months (approximately 6, 12, 18, and 24 months).

The study does not plan to terminate anyone’s participation early. They will continue in the study if they develop dementia, for as long as they and their legally authorized representative are willing to continue. For those unable to attend follow-up evaluations, we will offer a phone follow-up (CASI, survey questions, adverse events [AEs]). If a participant asks to withdraw, we will first ask them if we can contact them again in a few months. If they are unwilling, we will ask permission to follow via medical records only.

Intervention Procedures

SMARRT Intervention Arm

The SMARRT intervention team includes behavioral interventionists and a nurse care manager supported by a SMARRT clinical support team that includes a study physician and study psychologists. After baseline assessments have been completed, the intervention team will use a standardized procedure to develop an individualized Alzheimer’s Risk Profile for each participant randomized to the SMARRT intervention arm. This will include a graphic display of the targeted risk factors showing areas where the participant is doing well (green), areas where they can continue to improve (orange), and areas that are of particular risk for them (red). Participants will then meet in-person with an interventionist to review their risk profile and develop an initial personalized risk reduction action plan. Interventionists will elicit participants’ values and motivators to reduce Alzheimer’s risk and will use a decisional balance process informed by motivational interviewing and confidence ratings to help them choose 1–3 specific, achievable risk reduction steps that they are most ready to adopt. Participants will be provided with tools to track their progress. At each subsequent visit, interventionists will review progress, problem-solve barriers, and set new goals as needed. Following detailed protocols, the intervention team will provide counseling if participants experience distress related to being informed of their Alzheimer’s risk.

The specific goals and approaches for each risk factor are listed in Table 3. Targeted areas will include: increasing physical, mental and social activities; quitting smoking; healthy diet; controlling cardiovascular risk factors (diabetes, hypertension), including avoiding hypoglycemia in people with diabetes; reducing depressive symptoms; improving sleep; and decreasing use of potentially harmful medications. Interventionists will provide patients with a menu of options for each targeted risk factor, and goals will be individualized to preferences, barriers, and motivators to optimize intervention adherence. For each target, there are options that leverage technology as appropriate for the participants’ interest and skill level. Non-technology based options are provided for each target as well.

Table 3.

Targeted Risk Factors, Approaches and Outcomes in SMARRT

| Risk Factor | Goal | Menu of Options Tailored to Individual Preferences & Abilities | Outcome Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poorly controlled hypertension | <140/90 (<130/90 in patients with 10-year atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk ≥10%) | Exercise, diet, medication changes using stepped care “treat to target” approach with primary care provider (PCP) | Blood pressure (study visits; EHR) |

| Poorly controlled diabetes | Hemoglobin A1c between 7 and 8 | Exercise, diet, medication changes using stepped care “treat to target” approach with primary care | HbA1c (EHR) |

| Physical inactivity | Increase by 2500 steps/day OR maintain if they are over 10,000 steps/day OR work up to 8,000 steps per day | KPWA covered programs (e.g., Silver Sneakers, EnhanceFitness), community programs (e.g., YMCA, mall walking), smart phone apps (e.g., Apple Health, MyFitnessPal, MapMyWalk), wearable devices (e.g., pedometer, Fitbit), protocol to reduce sitting | Rapid Assessment of Physical Activity (RAPA) for Older Adults [35]; Actigraphy |

| Lack of mental stimulation | Increase engagement in cognitively stimulating activities that are enjoyable | Senior center activities, local college classes, crossword puzzles and games, cognitive training web programs, smart phone apps (e.g., Lumosity, Brain HQ), on-line classes, volunteering; mindfulness | Cognitive Activities Questionnaire [37] |

| Social isolation | Increase social engagement | Senior center activities, group exercise, social networking websites (e.g., Facebook), video chat tools, volunteering | PROMIS – Satisfaction with Participation in Discretionary Social Activities [36] |

| Depressive symptoms | Fewer depressive symptoms | Brief behavioral activation, Problem-solving Treatment -Primary Care (PST-PC),referral to behavioral health for cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), antidepressant medication via PCP, apps based on CBT (e.g,. MoodKit) | Center for Epidemiologic Studies – Depression Scale [40] |

| Sleep difficulty | Improvement on self-reported sleep quality and sleep duration | Sleep hygiene and sleep restriction education, CBT for Insomnia (CBT-I), apps (e.g. Sleepio), physical activity, behavioral activation | Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index [41] |

| Smoking | Reduction/cessation | Referral to Quit for Life, comprehensive program at no cost to KPWA members delivered by phone, web, or smart phone; mobile tools (NCI QuitPal) | Self-reported current tobacco usage |

| Unhealthy diet | Increase adherence to MIND diet | Education about neuroprotective foods, self-monitoring neuroprotective food intake with food logs or websites/apps (e.g. Fitbit, MyFitnessPal, MyPlate) | Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay (MIND) Diet Score [38] |

| Contraindicated medications | Elimination/minimization | Education on alternatives, including nonpharmacologic therapy; study physician contacts PCP with concerns and recommendations | Contra-indicated medications for cognition (2015 Beers criteria [48] and KPWA list) |

For management of medical conditions (e.g., hypertension, diabetes, depression, sleep disorders), a “treat-to-target” approach will be used. This will involve setting discrete goals for targeted conditions (e.g., blood pressure, HbA1c, depressive symptoms) in consultation with the participant and the primary care team, systematically monitoring participant progress, making suggestions to the participant and primary care team for adjusting treatment as needed (treat-to-target) and supporting participant self-care. Each week, the SMARRT intervention team will meet with the SMARRT clinical support team for case reviews. Treatment algorithms will be based on standard KPWA treatment recommendations synthesized from national guidelines. Approval to exercise will be obtained from primary care physicians (PCPs) to ensure participants can safely engage in exercise prior to receiving interventions. Those who are approved and interested will be encouraged to gradually increase their physical activity levels, focusing on walking. In addition, our protocol includes strategies to reduce sitting behavior as an alternative in those who are not interested or able to increase physical activity levels. The SMARRT study physician or nurse will make recommendations to the participant and their PCP about management of targeted medical conditions and use of specific high-risk medications via Epic messaging, a secure, electronic, internal messaging system that enables clinical staff to communicate with each other about patient care. A detailed list of contraindicated medications including generic and brand names was developed using the 2015 updated Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medications in older adults [48] and a Kaiser reference for high-risk medications in the elderly, focusing on medications that impact cognitive function. Examples of targeted medications include those with strong anticholinergic properties, such as some antihistamines (e.g., diphenhydramine), some antidepressants (e.g., amitriptyline, paroxetine), and sedative-hypnotics (e.g., alprazolam, lorazepam). Nurses will work collaboratively with the primary care team to deprescribe contraindicated medications, and health coaches will work with participants on behavioral approaches to manage underlying conditions such as depression or insomnia. Prior studies have shown that simple educational interventions regarding risky medications can substantially reduce usage in older patients [49].

Interventionists will follow a standard protocol for delivering the SMARRT intervention that allows for personalization of the specific risk reduction action plan; these plans will evolve over time according to participant progress, motivation and preferences or newly identified risk factors. Staff will use a tracking database to record information for each participant, including date and time of session, identified risk factors, motivational barriers and important values, and the outcome of discussions around developing goals. For each participant, the exact number and mode (phone or in-person) of contacts will differ, but we will aim to have at least 1 contact per month with each participant. Best practice will include in-person meetings twice a year during the 2-year intervention period. Even if a participant has relatively fewer risk factors, or successfully addresses all of their risk factors, interventionists will continue to check in with them to ensure that they are maintaining their healthy behaviors over time.

Health Education (HE) Control Arm

In this pragmatic pilot trial, our goal is to compare the personalized SMARRT intervention to what is currently ‘usual care’ in the healthcare system, while also providing enough interaction to maintain retention and blinding. Therefore, participants randomized to the Health Education (HE) group will receive mailed materials (typically 1–2 pages) every 3 months. This will include general information on Alzheimer’s and dementia risk reduction using materials from sources such as the Alzheimer’s Association and educational materials commonly provided as part of routine care at KPWA. The information will address factors that will be targeted in the SMARRT intervention, including physical, mental and social engagement; management of cardiovascular risk factors; quitting smoking, healthy diet; depression; sleep; and contraindicated medications. HE participants will not be provided with personalized information about their risk of Alzheimer’s and dementia.

Adherence Assessment

Interventionists will use the tracking database to carefully document each contact with participants, including the type (in person, phone) and outcome (risk factor targeted, goal, whether the goal was met, comments). This will enable us to determine the total number and type of contacts per participant, the number and types of risk factors targeted, and the extent to which goals were achieved. Interventionists also will document weekly case review recommendations with the clinical support team to supply information about intervention adherence. In the control arm, there is no active intervention (only passive materials, usual care) so we cannot assess adherence or engagement.

Safety Assessments

Data and Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB)

This study will be monitored by an external Data and Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB), which will act in an advisory capacity to the National Institute on Aging (NIA) and the PIs to monitor participant safety, data quality, and the progress of the study. Members of the DSMB are listed in the Appendix.

Adverse Events (AEs) and Serious Adverse Events (SAEs)

We expect AEs associated with this intervention to be minimal and consistent with risks of daily life (e.g., anxiety caused by clinical assessments, muscle aches from physical activity). AEs will be tracked in the study database. We will use a multipronged approach to collect information about AEs, including active as well as passive modes. We will collect information through: reports or contact with study participants, surveys specifically asking about AEs, and data in the EHR. All participants will be prompted to report AEs and SAEs at their follow-up assessment visits (approximately 6, 12, 18, and 24 months). Those in the SMARRT group may also report AEs during check-ins with interventionists. Those in the HE group will be asked to respond to an AE form sent in the mail every three months (approximately months 3, 9, 15, and 21) when new health education materials are sent. SAEs will be reported immediately to the project PIs and to the Institutional Review Board (IRB) and DSMB. All interviewers, nurses, and other study staff will be trained to identify potential AEs. These would include participant, family member, or physician complaints; threats to withdraw or actual withdrawals from the study; and responses to questionnaire items indicating risk of serious consequences.

Intervention Discontinuation

Study participants may withdraw at any time for any reason. Participants will continue to be followed, with their permission, even if the study intervention is discontinued. Follow-up measurement visits will continue to be scheduled if the participant is willing. If not, the study team will follow-up via by phone calls and/or medical record review, as allowed by the participant.

Statistical Considerations

General Design Issues

The primary outcome will be a global cognitive function composite score. To calculate the composite score, each raw test score will be standardized based on the mean/standard deviation from all participants at baseline. Then, the resulting z-scores will be averaged across tests. Secondary outcomes will include change in Alzheimer’s risk factors, individual cognitive domain scores, physical performance, functional ability, quality of life and incidence of MCI and dementia. Our hypotheses include the following:

We hypothesize that composite cognitive function scores among participants randomized to the SMARRT intervention arm will show improvement and/or less decline, relative to those in the control arm.

We hypothesize that participants in the SMARRT intervention will show improvements on Alzheimer’s risk factors during the intervention, relative to those in the control arm.

We hypothesize that additional outcomes including individual cognitive domain z-scores, physical performance, functional ability, and quality of life will be improved by the intervention. We also hypothesize that incidence of MCI and Alzheimer’s will be lower among participants in the SMARRT arm.

Sample Size

Because this is a pilot trial, our goal is to estimate effect sizes for a larger trial. Therefore, sample size estimates are based primarily on considerations of precision rather than power and effect size. For our primary outcome, our sample size of 200 will enable us to estimate the effect size with a precision of +/− 0.08 SDs, assuming loss to follow-up of 10% and intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.6 based on data from the FINGER trial [23]. This estimate will be used in combination with a consensus clinically meaningful effect, based on the literature and investigator expertise. For secondary outcomes, we estimate that precision will range from +/− 0.06 SDs to +/− 0.08 SDs, depending on the ICC. We anticipate that conversion to MCI/AD in this two-year trial will be low (<10%); therefore, this outcome is considered exploratory.

Data Analyses

We will first assess balance on baseline characteristics of the SMARRT and HE groups using graphical and tabular checks for overlap, and statistical comparisons using t-tests, Wilcoxon, chi-square, and Fisher’s exact tests as appropriate. All analyses will use intent-to-treat principles.

To estimate the effect of SMARRT compared to HE on our primary outcome, repeated measures of the composite cognitive function score obtained at 0, 6, 12, 18 and 24 months, we will use a linear mixed model (LMM), with fixed effects for the baseline score, time, treatment, and the time-by-treatment interaction, as well as random intercepts and slopes. Exploratory analyses will be performed within the intervention group to determine whether there is evidence that the magnitude of the effect varies based on the number or types of risk factors targeted, the extent to which goals are achieved, or the number or type of interventionist contacts. These analyses will be restricted to the intervention group because among controls, the number and type of risk factors targeted will not be assessed, achievement of goals will be undefined, and the number and type of contacts will differ systematically by design. Hence these results will be descriptive and will not estimate effect modification, mediation or dose-response, respectively. We also will use multiple imputation to explore the impact of missing data.

Similar methods will be used to assess the effect of the intervention on changes in Alzheimer’s risk factors over two years. Because this is a pilot study, we chose not to pre-specify the benchmarks for change/improvement for each risk factor. Instead, we will quantify the amount of change achieved for each risk factor. Generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs), also with fixed effects for the baseline value, time, treatment, and the time-by-treatment interaction, and random intercepts and slopes, will be used as appropriate to assess treatment effects on binary, count, ordinal, and multinomial risk factors, including the number of risk factors.

LMMs and GLMMs also will be used to compare the impact of SMARRT vs. HE on individual cognitive domain z-scores, physical performance, functional ability, and quality of life. Finally, Cox proportional hazards models will be used to analyze intervention effects on time to MCI and AD.

Data Collection and Quality Assurance

Data Collection Forms

Outcome assessments will be performed by trained research specialists who will be blinded to group assignments. Most measures during the outcome assessments will be collected using paper forms. The data from these forms will be entered by the assessors into a secure, web-based system overseen by UCSF. Participants will complete questionnaires via a touch-screen tablet computer. The participants’ responses on those questionnaires will be automatically scored and entered into the web-based database. Paper forms will be available as back-ups if needed.

Data Management

All data will be collected by KPWHRI staff in KPWA facilities. Data will be collected and stored separately for enrollment and intervention activities and outcome assessments. Enrollment and intervention data will be collected and stored within KPWHRI. Outcome data will be entered into UCSF’s secure web-based data entry site, called REDCap.

Quality Assurance

Standardized training procedures will be implemented for all study personnel and will be included in a detailed Manual of Operating Procedures. Interventionists will have master’s degrees in relevant health-related areas (e.g. public health, social work) and will be trained by two licensed clinical psychologists to deliver motivational interviewing, problem solving treatment, and general health coaching for all health behaviors. They will be trained using didactic techniques, role-play, and direct observation of at least two initial sessions and two follow-up sessions with corrective feedback. Outcome assessors will be trained to administer the neuropsychological test battery by the study neuropsychologist, who will review audio recordings and data records of cognitive test battery administration from at least two of the first 10 assessment visits for quality assurance and to provide corrective feedback. Similar procedures will be used to train outcome assessors on secondary outcome measures.

Data for a random sample of 10% of study participants will be double-entered to determine the extent of data entry error and adjust if indicated.

CONCLUSION

The Systematic Multi-domain Alzheimer’s Risk Reduction Trial (SMARRT) will provide important pilot data regarding the effects of a personalized, Alzheimer’s risk reduction program delivered through an integrated healthcare system. If our hypotheses are supported, we plan to perform a larger multi-site trial to determine whether the SMARRT intervention can delay onset of MCI and AD in high-risk older adults. Given the projected rise in Alzheimer’s prevalence and the lack of disease-modifying medications, it is critically important to test the efficacy of pragmatic preventative interventions such as SMARRT. If SMARRT proves to be effective in this setting, it could be adapted and disseminated to other health care delivery settings in other countries. Ultimately, multi-domain interventions such as SMARRT have the potential to help address the global burden of dementia by promoting brain-healthy activities to reduce risk and delay onset of Alzheimer’s and dementia.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study is funded by the National Institute on Aging (1R01AG057508). The Principal Investigators are Kristine Yaffe, MD, University of California, San Francisco, and Eric B. Larson, MD, MPH, Kaiser Permanente Washington Research Institute. Key personnel are listed in the Appendix. The study protocol was developed using the National Institute on Aging Clinical Intervention Study Protocol Template (https://www.nia.nih.gov/research/dgcg/clinical-research-study-investigators-toolbox/startup). This manuscript reflects protocol version 1.2, which was approved by the Data and Safety Monitoring Board on May 31, 2018. This trial has been registered on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03683394).

REFERENCES

- [1].Alzheimer’s Disease International (2015) Alzheimer’s Disease International (ADI), London. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Alzheimer’s Association (2017) 2017 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement 13, 325–373. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Atri A, Frolich L, Ballard C, Tariot PN, Molinuevo JL, Boneva N, Windfeld K, Raket LL, Cummings JL (2018) Effect of Idalopirdine as Adjunct to Cholinesterase Inhibitors on Change in Cognition in Patients With Alzheimer Disease: Three Randomized Clinical Trials. JAMA 319, 130–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Bezprozvanny I (2010) The rise and fall of Dimebon. Drug News Perspect 23, 518–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Cummings JL, Morstorf T, Zhong K (2014) Alzheimer’s disease drug-development pipeline: few candidates, frequent failures. Alzheimers Res Ther 6, 37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Fagan T (August 8, 2012) in Alzheimer Research Forum online.

- [7].Fagan T (August 18, 2010) in Alzheimer Research Forum online.

- [8].Honig LS, Vellas B, Woodward M, Boada M, Bullock R, Borrie M, Hager K, Andreasen N, Scarpini E, Liu-Seifert H, Case M, Dean RA, Hake A, Sundell K, Poole Hoffmann V, Carlson C, Khanna R, Mintun M, DeMattos R, Selzler KJ, Siemers E (2018) Trial of Solanezumab for Mild Dementia Due to Alzheimer’s Disease. N Engl J Med 378, 321–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Jeffrey S (May 7, 2013) in Medscape Today

- [10].Salloway S, Sperling R, Fox NC, Blennow K, Klunk W, Raskind M, Sabbagh M, Honig LS, Porsteinsson AP, Ferris S, Reichert M, Ketter N, Nejadnik B, Guenzler V, Miloslavsky M, Wang D, Lu Y, Lull J, Tudor IC, Liu E, Grundman M, Yuen E, Black R, Brashear HR, Bapineuzumab, Clinical Trial I (2014) Two phase 3 trials of bapineuzumab in mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med 370, 322–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Larson EB, Yaffe K, Langa KM (2013) New insights into the dementia epidemic. N Engl J Med 369, 2275–2277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Yaffe K (2018) Modifiable Risk Factors and Prevention of Dementia: What Is the Latest Evidence? JAMA Intern Med 178, 281–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Barnes DE, Yaffe K (2011) The projected effect of risk factor reduction on Alzheimer’s disease prevalence. Lancet Neurol 10, 819–828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Norton S, Matthews FE, Barnes DE, Yaffe K, Brayne C (2014) Potential for primary prevention of Alzheimer’s disease: an analysis of population-based data. Lancet Neurol 13, 788–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Langa KM, Larson EB, Crimmins EM, Faul JD, Levine DA, Kabeto MU, Weir DR (2017) A Comparison of the Prevalence of Dementia in the United States in 2000 and 2012. JAMA Intern Med 177, 51–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Manton KC, Gu XL, Ukraintseva SV (2005) Declining prevalence of dementia in the U.S. elderly population. Adv Gerontol 16, 30–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Matthews FE, Arthur A, Barnes LE, Bond J, Jagger C, Robinson L, Brayne C, Medical Research Council Cognitive F, Ageing C (2013) A two-decade comparison of prevalence of dementia in individuals aged 65 years and older from three geographical areas of England: results of the Cognitive Function and Ageing Study I and II. Lancet 382, 1405–1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Qiu C, von Strauss E, Backman L, Winblad B, Fratiglioni L (2013) Twenty-year changes in dementia occurrence suggest decreasing incidence in central Stockholm, Sweden. Neurology 80, 1888–1894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Rocca WA, Petersen RC, Knopman DS, Hebert LE, Evans DA, Hall KS, Gao S, Unverzagt FW, Langa KM, Larson EB, White LR (2011) Trends in the incidence and prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease, dementia, and cognitive impairment in the United States. Alzheimers Dement 7, 80–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Schrijvers EM, Verhaaren BF, Koudstaal PJ, Hofman A, Ikram MA, Breteler MM (2012) Is dementia incidence declining?: Trends in dementia incidence since 1990 in the Rotterdam Study. Neurology 78, 1456–1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Wu YT, Beiser AS, Breteler MMB, Fratiglioni L, Helmer C, Hendrie HC, Honda H, Ikram MA, Langa KM, Lobo A, Matthews FE, Ohara T, Peres K, Qiu C, Seshadri S, Sjolund BM, Skoog I, Brayne C (2017) The changing prevalence and incidence of dementia over time - current evidence. Nat Rev Neurol 13, 327–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Lee KS, Lee Y, Back JH, Son SJ, Choi SH, Chung YK, Lim KY, Noh JS, Koh SH, Oh BH, Hong CH (2014) Effects of a multidomain lifestyle modification on cognitive function in older adults: an eighteen-month community-based cluster randomized controlled trial. Psychother Psychosom 83, 270–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Ngandu T, Lehtisalo J, Solomon A, Levalahti E, Ahtiluoto S, Antikainen R, Backman L, Hanninen T, Jula A, Laatikainen T, Lindstrom J, Mangialasche F, Paajanen T, Pajala S, Peltonen M, Rauramaa R, Stigsdotter-Neely A, Strandberg T, Tuomilehto J, Soininen H, Kivipelto M (2015) A 2 year multidomain intervention of diet, exercise, cognitive training, and vascular risk monitoring versus control to prevent cognitive decline in at-risk elderly people (FINGER): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 385, 2255–2263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Rosenberg A, Ngandu T, Rusanen M, Antikainen R, Backman L, Havulinna S, Hanninen T, Laatikainen T, Lehtisalo J, Levalahti E, Lindstrom J, Paajanen T, Peltonen M, Soininen H, Stigsdotter-Neely A, Strandberg T, Tuomilehto J, Solomon A, Kivipelto M (2018) Multidomain lifestyle intervention benefits a large elderly population at risk for cognitive decline and dementia regardless of baseline characteristics: The FINGER trial. Alzheimers Dement 14, 263–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Andrieu S, Guyonnet S, Coley N, Cantet C, Bonnefoy M, Bordes S, Bories L, Cufi MN, Dantoine T, Dartigues JF, Desclaux F, Gabelle A, Gasnier Y, Pesce A, Sudres K, Touchon J, Robert P, Rouaud O, Legrand P, Payoux P, Caubere JP, Weiner M, Carrie I, Ousset PJ, Vellas B, Group MS (2017) Effect of long-term omega 3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation with or without multidomain intervention on cognitive function in elderly adults with memory complaints (MAPT): a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol 16, 377–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Lam LC, Chan WC, Leung T, Fung AW, Leung EM (2015) Would older adults with mild cognitive impairment adhere to and benefit from a structured lifestyle activity intervention to enhance cognition?: a cluster randomized controlled trial. PLoS One 10, e0118173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Moll van Charante EP, Richard E, Eurelings LS, van Dalen JW, Ligthart SA, van Bussel EF, Hoevenaar-Blom MP, Vermeulen M, van Gool WA (2016) Effectiveness of a 6-year multidomain vascular care intervention to prevent dementia (preDIVA): a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 388, 797–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Teng EL, Hasegawa K, Homma A, Imai Y, Larson E, Graves A, Sugimoto K, Yamaguchi T, Sasaki H, Chiu D, et al. (1994) The Cognitive Abilities Screening Instrument (CASI): a practical test for cross-cultural epidemiological studies of dementia. Int Psychogeriatr 6, 45–58; discussion 62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Kukull WA, Higdon R, Bowen JD, McCormick WC, Teri L, Schellenberg GD, van Belle G, Jolley L, Larson EB (2002) Dementia and Alzheimer disease incidence: a prospective cohort study. Arch Neurol 59, 1737–1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Corrada MM, Brookmeyer R, Paganini-Hill A, Berlau D, Kawas CH (2010) Dementia incidence continues to increase with age in the oldest old: the 90+ study. Ann Neurol 67, 114–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Charlson M, Szatrowski TP, Peterson J, Gold J (1994) Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J Clin Epidemiol 47, 1245–1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Kivipelto M, Solomon A, Ahtiluoto S, Ngandu T, Lehtisalo J, Antikainen R, Backman L, Hanninen T, Jula A, Laatikainen T, Lindstrom J, Mangialasche F, Nissinen A, Paajanen T, Pajala S, Peltonen M, Rauramaa R, Stigsdotter-Neely A, Strandberg T, Tuomilehto J, Soininen H (2013) The Finnish Geriatric Intervention Study to Prevent Cognitive Impairment and Disability (FINGER): study design and progress. Alzheimers Dement 9, 657–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Harrison J, Minassian SL, Jenkins L, Black RS, Koller M, Grundman M (2007) A neuropsychological test battery for use in Alzheimer disease clinical trials. Arch Neurol 64, 1323–1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Harrison J, Rentz DM, McLaughlin T, Niecko T, Gregg KM, Black RS, Buchanan J, Liu E, Grundman M, Group E-A-SI (2014) Cognition in MCI and Alzheimer’s disease: baseline data from a longitudinal study of the NTB. Clin Neuropsychol 28, 252–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Topolski TD, LoGerfo J, Patrick DL, Williams B, Walwick J, Patrick MB (2006) The Rapid Assessment of Physical Activity (RAPA) among older adults. Prev Chronic Dis 3, A118. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Hahn EA, Beaumont JL, Pilkonis PA, Garcia SF, Magasi S, DeWalt DA, Cella D (2016) The PROMIS satisfaction with social participation measures demonstrated responsiveness in diverse clinical populations. J Clin Epidemiol 73, 135–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Vemuri P, Lesnick TG, Przybelski SA, Machulda M, Knopman DS, Mielke MM, Roberts RO, Geda YE, Rocca WA, Petersen RC, Jack CR Jr. (2014) Association of lifetime intellectual enrichment with cognitive decline in the older population. JAMA Neurol 71, 1017–1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Morris MC, Tangney CC, Wang Y, Sacks FM, Barnes LL, Bennett DA, Aggarwal NT (2015) MIND diet slows cognitive decline with aging. Alzheimers Dement 11, 1015–1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Morris MC, Tangney CC, Wang Y, Sacks FM, Bennett DA, Aggarwal NT (2015) MIND diet associated with reduced incidence of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 11, 1007–1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Radloff LS (1977) The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement 1, 385–401. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ (1989) The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res 28, 193–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, Glynn RJ, Berkman LF, Blazer DG, Scherr PA, Wallace RB (1994) A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J Gerontol 49, M85–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Amariglio RE, Donohue MC, Marshall GA, Rentz DM, Salmon DP, Ferris SH, Karantzoulis S, Aisen PS, Sperling RA, Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative S (2015) Tracking early decline in cognitive function in older individuals at risk for Alzheimer disease dementia: the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study Cognitive Function Instrument. JAMA Neurol 72, 446–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Hays RD, Bjorner JB, Revicki DA, Spritzer KL, Cella D (2009) Development of physical and mental health summary scores from the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) global items. Qual Life Res 18, 873–880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Petersen RC, Lopez O, Armstrong MJ, Getchius TSD, Ganguli M, Gloss D, Gronseth GS, Marson D, Pringsheim T, Day GS, Sager M, Stevens J, Rae-Grant A (2018) Practice guideline update summary: Mild cognitive impairment: Report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 90, 126–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, Bennett DA, Craft S, Fagan AM, Iwatsubo T, Jack CR Jr., Kaye J, Montine TJ, Park DC, Reiman EM, Rowe CC, Siemers E, Stern Y, Yaffe K, Carrillo MC, Thies B, Morrison-Bogorad M, Wagster MV, Phelps CH (2011) Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 7, 280–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Winblad B, Palmer K, Kivipelto M, Jelic V, Fratiglioni L, Wahlund LO, Nordberg A, Backman L, Albert M, Almkvist O, Arai H, Basun H, Blennow K, de Leon M, DeCarli C, Erkinjuntti T, Giacobini E, Graff C, Hardy J, Jack C, Jorm A, Ritchie K, van Duijn C, Visser P, Petersen RC (2004) Mild cognitive impairment--beyond controversies, towards a consensus: report of the International Working Group on Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Intern Med 256, 240–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].By the American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria Update Expert P (2015) American Geriatrics Society 2015 Updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 63, 2227–2246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Tannenbaum C, Martin P, Tamblyn R, Benedetti A, Ahmed S (2014) Reduction of inappropriate benzodiazepine prescriptions among older adults through direct patient education: the EMPOWER cluster randomized trial. JAMA Intern Med 174, 890–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Li C, Friedman B, Conwell Y, Fiscella K (2007) Validity of the Patient Health Questionnaire 2 (PHQ-2) in identifying major depression in older people. J Am Geriatr Soc 55, 596–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Kroenke K, Strine TW, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Berry JT, Mokdad AH (2009) The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. J Affect Disord 114, 163–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.