Abstract

Background:

Hypomyelinating leukodystrophies are a heterogeneous group of genetic disorders with a wide spectrum of phenotypes and a high rate of genetically unsolved cases. Bi-allelic mutations in NKX6–2 were recently linked to spastic-ataxia 8 with hypomyelinating leukodystrophy (SPAX8).

Methods:

Using a combination of homozygosity mapping, exome sequencing, detailed clinical and neuroimaging assessment we describe a series of new NKX6–2 mutations in a multicentre setting. We then combined all reported NKX6–2 mutations, combining all reported NKX6–2 mutations, analyzing spectrum of NKX6–2-related disease.

Results:

We identified 11 new cases from 8 families of different ethnic backgrounds carrying compound heterozygous and homozygous pathogenic variants in NKX6–2, evidencing a high NKX6–2 mutation burden in the hypomyelinating leukodystrophy disease spectrum. Our data reveals a phenotype spectrum with neonatal onset, global psychomotor delay and worse prognosis at the severe end and a childhood onset with mainly motor phenotype at the milder end. We describe the phenotypic and neuroimaging expression in NKX6–2 and show that phenotypes with epilepsy in the absence of overt hypomyelination and diffuse hypomyelination without seizures can occur.

Conclusions:

We show that NKX6–2 mutations should be considered in patients with autosomal recessive, very early onset of nystagmus, cerebellar ataxia with hypotonia that rapidly progresses to spasticity, particularly when associated with neuroimaging signs of hypomyelination. Therefore, we recommend that NXK6–2 should be included in hypomyelinating leukodystrophy and spastic-ataxia diagnostic panels.

Keywords: spastic ataxia 8, SPAX8, NKX6–2, hypomyelination, leukodystrophy

INTRODUCTION

Hypomyelinating leukodystrophies are a heterogeneous group of genetic disorders with a wide spectrum of phenotypes. Given that myelination is a highly regulated process these disorders usually result from genetic abnormalities. However, the majority of individuals with hypomyelinating disorders have no genetic diagnosis [1].

Hypomyelination can result from dysfunctions in myelin generation or maintenance pathways including mutations in the myelin proteins (PLP1), protein translation (POLR3A, POLR3B, POLR1C) and gap junction proteins linking astrocytes and oligodendrocytes (GJC2).

We have recently described a new phenotype associated with bi-allelic mutations in NKX6–2 leading to spastic-ataxia 8 (SPAX8), autosomal recessive, with hypomyelinating leukodystrophy (OMIM: 617560) [2]. The reported NKX6–2 mutations were bi-allelic truncating or located in the highly conserved homeobox domain. Clinically, they presented with early onset spastic-ataxia or hypotonia progressing to severe spasticity within a few months and were associated with hypomyelination [2].

Here, we present a large, ethnically diverse cohort, describing comprehensively an expanding clinical and neuroimaging syndrome and a large genotypic spectrum of NKX6–2-related disease.

METHODS

The study included affected individuals with spastic-ataxia and hypomyelination from unrelated families of different ethnic backgrounds. Families were recruited under Institutional Review Board/ethics-approved research protocols (UCLH: 04/N034) with informed consent. For comprehensive genotype-phenotype analyses we included all reported genetically diagnosed NKX6–2 mutations. Extended methods are in Supplementary S1.

RESULTS

Genotype spectrum in NKX6–2-related disease

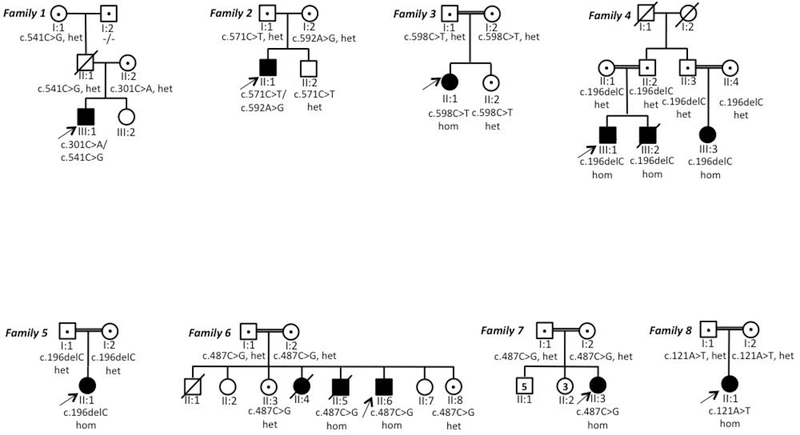

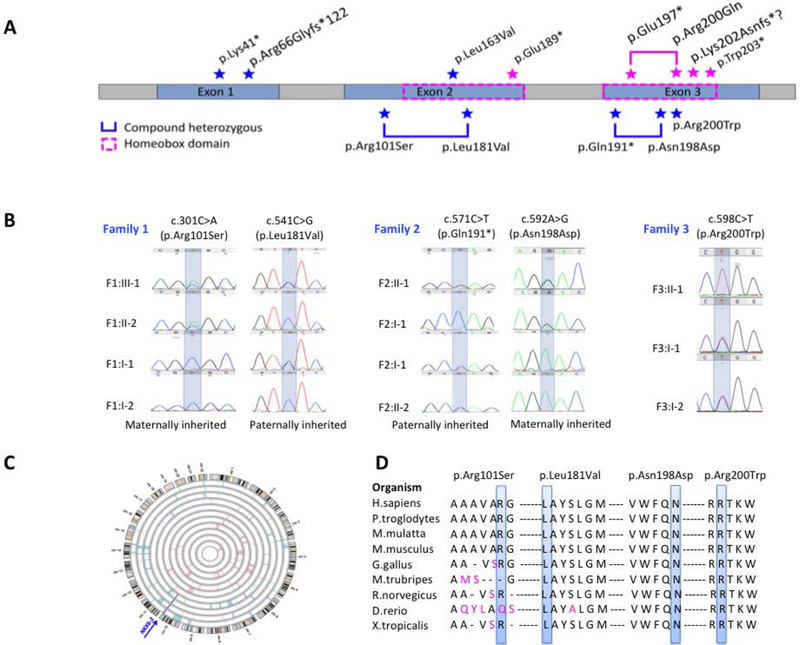

In this study we identified 11 new cases from 8 families (Figure 1) carrying pathogenic variants in NKX6–2. Eight distinct mutations were found including 4 were novel variants (Figure 2A). One was present in gnomAD with very low allele frequency in heterozygous state (MAF 0.0001170) but absent as homozygous (c.541C>G) (Figure 2B), and three were known pathogenic variants. The c.196delC identified in family IV and V was present in a shared homozygous region (Figure 2C). All missense variants were located in conserved amino acid positions (Figure 2D).

Figure 1. Family trees in all new families reported in this study.

het=heterozygous; hom= homozygous; the individuals tested in this study are indicated with a dot.

Figure 2. Mutation spectrum of NKX6–2–related disease.

A. NKX6–2 gene with all the mutations identified. All known and novel mutations identified in our cohort are labeled in blue star; all mutations previously reported are labeled in magenta star and plotted on top of the gene.

B. Sanger sequencing confirmation with segregation analysis for novel NKX6–2 variants reported in this study.

C. Homozygozity mapping in family IV and V identified a homozygous region on chromosome 10, shared by affected individuals and containing the pathogenic homozygous variant c.196delC in NKX6–2.

D. Conservation across species of each novel missense mutation reported in this study.

We extended our analysis to include 33 individuals from 21 families carrying NKX6–2 mutations identified in this study and previously reported [2–5] (Table 1, Supplementary S2–S3). So far, 13 distinct NKX6–2 variants have been linked to SPAX8 disease. Several mutations (c.121A>T, c.487C>G, c.196delC) were reported in multiple families. The c.196delC and c.487C>G were identified in 5 families each, all originally from the Middle East. Haplotype analysis from three families confirmed that c.196delC was a founder mutation. However, the c.487C>G carriers didn’t share same haplotype, the mutation arising recurrently [5]. The c.121A>T was identified in three families of Indian origin. Haplotype analysis data from two of these families confirmed a founder effect [2].

Table 1.

Variant description of all NXK6–2 mutations reported to date.

| Zygosity | c.DNA change |

Amino acid change |

Type of mutation |

Novel/ Known |

ACMG score | ACMG classification |

Onset | Phenotype | Additional signs reported |

Hypomyelination | Cerebellar atrophy |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound heterozygous | c.301C>A | p.Arg101Ser | Missense | Novel | PM2, PM3, PP1, PP3 | Likely pathogenic | Childhood | Predominantly motor delay | Seizures | Mild | Yes | This study |

| c.541C>G | p.Leu181Val | Missense | Known (rs369901030) (MAF= 0.0001170) | PM1, PM3, PP1, PP3 | Likely pathogenic | This study | ||||||

| Compound heterozygous | c.571C>T | p.Gln191* | Nonsense | Novel | PVS1, PM1, PM2, PM3, PP1 | Pathogenic | Neonatal | Severe global psychomotor delay | No | Diffuse, severe | No | This study |

| c.592A>G | p.Asn198Asp | Missense | Novel | PM1, PM2, PM3, PP1 | Likely pathogenic | This study | ||||||

| Homozygous | c.598C>T | p.Arg200Trp | Missense | Novel | PS1, PM1, PM2, PM3, PP1 | Pathogenic | Neonatal | Severe global psychomotor delay | No | Diffuse, severe | Yes | This study |

| Homozygous | c.121A>T | p.Lys41* | Nonsense | Known | PVS1, PS3, PM2, PM3, PP1 | Pathogenic | Childhood | Predominantly motor delay | Dystonia. Limitation of eye movements | Diffuse, severe | Yes | This study, Chelban et al1 |

| Homozygous | c.196delC | p.Arg66Glyfs*122 | Frameshift | Known | PVS1, PM2, PM3, PP1 | Pathogenic | Neonatal | Severe global psychomotor delay | Limitation of eye movements, hearing impairment. Gastrostomy for severe dysphagia. Scoliosis | Diffuse, severe | No | This study, Anazi et al2, Baldi et al3 |

| Homozygous | c.487C>G | p.Leu163Val | Missense | Known | PM1, PM2, PM3, PP1 | Likely pathogenic | Neonatal | Severe global psychomotor delay | Seizures. Gastrostomy for severe dysphagia. | Variable. 2 cases reported with no hypomyelination | Yes | This study, Chelban et al1, Baldi et al3 |

| Homozygous | c.565G>T | p.Glu189* | Nonsense | Known | PVS1, PM1, PM2, PM3, PP1 | Pathogenic | Neonatal | Severe global psychomotor delay | Severe dystonia | Diffuse, severe | Yes | Dorboz et al4 |

| Compound heterozygous | c.589C>T | p.Gln197* | Nonsense | Known | PVS1, PM1, PM2, PM3, PP1 | Pathogenic | Neonatal | Severe global psychomotor delay | Swallowing difficulties. Poor visual acuity | Diffuse, severe | No | Dorboz et al4 |

| c.599G>A | p.Arg200Gln | Missense | Known | PM1, PM2, PM3, PP1 | Likely pathogenic | |||||||

| Homozygous | c.606delinsTA | p.Lys202Asnfs?1 | Frameshift | Known | PVS1, PM1, PM2, PM3, PP1 | Pathogenic | Neonatal | Severe global psychomotor delay | Severe dystonia | Diffuse, severe | Yes | Dorboz et al4 |

| Homozygous | c.608G>A | p.Trp203* | Nonsense | Known | PVS1, PM1, PM2, PM3, PP1 | Pathogenic | Neonatal | Severe global psychomotor delay | Seizures | Diffuse, severe | No | Baldi et al3 |

AA =amino acid; Comp. het. = compound heterozygous; Homoz.=homozygous;

Chelban V, Patel N, Vandrovcova J, et al. Mutations in NKX6–2 Cause Progressive Spastic Ataxia and Hypomyelination. American journal of human genetics. 2017;100(6):969–977.

Anazi S, Maddirevula S, Salpietro V, et al. Expanding the genetic heterogeneity of intellectual disability. Human genetics. 2017;136(11–12):1419–1429.

Baldi C, Bertoli-Avella AM, Al-Sannaa N, et al. Expanding the clinical and genetic spectra of NKX6–2-related disorder. Clinical genetics. 2018.

Dorboz I, Aiello C, Simons C, et al. Biallelic mutations in the homeodomain of NKX6–2 underlie a severe hypomyelinating leukodystrophy. Brain : a journal of neurology. 2017;140(10):2550–2556.

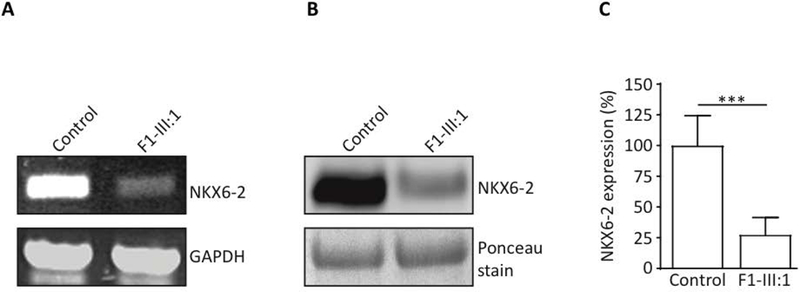

With one exception (p.Arg101Ser), all missense mutations affected the Homeobox domain. To establish the deleterious effect of p.Arg101Ser variant we performed RT-PCR and WB. Control RT-PCR for glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) confirmed the presence of cDNA in all samples. In the patient, NKX6–2 cDNA was severely reduced compared to controls (Figure 3A). Immunoblot analysis confirmed significant reduction in NKX6–2 protein levels in the patient compared to controls (Figure 3B–C, Supplementary 4).

Figure 3. Functional analyses and pathogenicity of variants identified in Family 1.

A. Reverse transcription PCR in compound heterozygous missense case F1-III:1 showed absent or severely reduced NKX6–2 compared to control (CTR); glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) used as a loading control.

B. Reduced NKX6–2 protein levels confirmed by Western blot in individual F1-III:1. Total protein lysate extracted from human fibroblasts assessed by SDS-PAGE and analysed by western blotting using anti-NKX6–2 antibody (left panel).

C. Densitometry analysis shows significant reduction in NKX6–2 protein levels in fibroblasts harbouring the NKX6–2 missense mutation compared to control cells. *** p < 0.01, replicate values, mean and SD are shown; one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test.

The majority of reported cases (81.8%, 27/33) presented in the first year of life, half of these (14/27) as neonates. We analyzed whether the mutation type influenced the age of onset. Sixteen cases carried two truncating alleles, 13 had bi-allelic missense mutations and four had compound heterozygous variants including one truncating mutation. Although an earlier mean onset age was observed in the group harboring 2 truncating alleles, versus the group with 2 missense alleles (7.3 months vs 8.3 months), the difference was not statistically significant (p=0.78).

Phenotype spectrum in NKX6–2-related disease

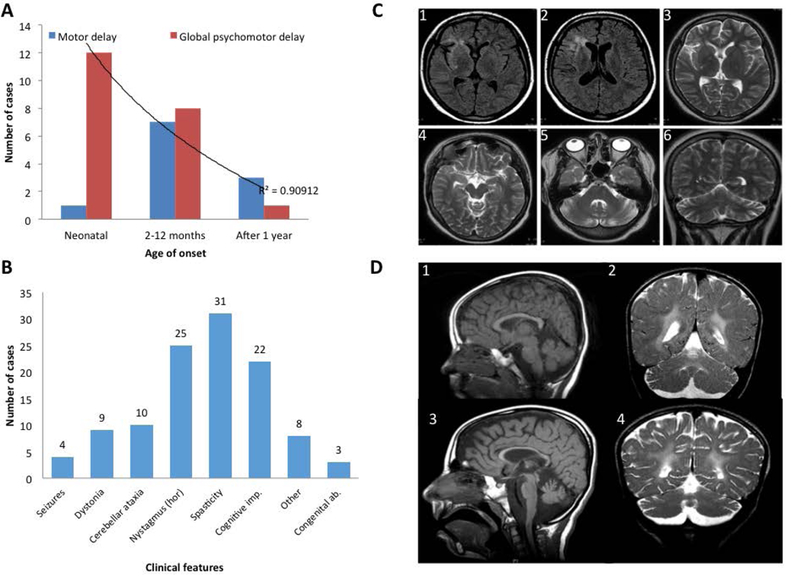

Assessment of the age of onset and disease severity revealed two ends of an expanding phenotype spectrum of NKX6–2 mutations.

Neonatal and very early onset

Neonatal onset was associated with higher rate of severe global psychomotor disability when compared with onset after 1 month old (p=0.05) (Figure 4A). Twenty cases with information on motor milestones showed very severe motor deficit; all children failing to achieve independent ambulation and 70% (14/20) failing to achieve head control. Furthermore, 90% of children with disease onset before one year never achieved verbal milestones/meaningful speech.

Figure 4. Genetype-phenotype correlation and neuroimaging spectrum of NKX6–2 mutations.

A. The neonatal onset group has statistically significant higher frequency of global psychomotor developmental delay (red) compared with the other 2 groups (onset from 2 months -1 year and onset after 1 year). Childhood onset is associated with predominantly motor delay (blue). P=0.05, r2=0.9). n.s=not significant.

B. Clinical features associated with NKX6–2 mutations (the horizontal axis), the number of cases on the vertical axis (total n=33). Hor =horizontal, gaze evoked nystagmus.

C. FLAIR and T2 weighted MRI acquisitions from case F1-III:1 exhibiting T2 hyperintense signal change in periventricular WM surrounding the frontal horn of the right lateral ventricle, and frontal and temporal opercular and subinsular WM T2 weighted hyperintense signal change associated with a degree of cortical volume loss. Note the normal signal intensity of the globi pallidi, thalami, and external capsules, mesencephalon and pons. There is disproportionate cerebellar volume loss with mild T2-weighted hyperintense signal change in the peri-dentate WM.

D. Longitudinal MRI in case F7-II:3 at ages of 4 years (D1, D2) and 8 ½ years (D3, D4)(D1, D3-mid-sagittal T1-weighted; D2, D4-coronal T2-weighted) showing progressive thinning of the corpus callosum and cerebellar atrophy associated with WM abnormality sparing the U fibers (2,4). There is progressive enlargement of the cortical sulci and extra axial CSF spaces indicating underlying global brain atrophy.

Complex medical needs included severe dysphagia requiring gastrostomy (6/33 cases), congenital heart disease (1/33), respiratory failure (2/33) leading to death, undescended testicles (1/33), severe dental and/or gum abnormalities (6/33 cases), inguinal hernia (1/33). Survival in this group was shorter with 12.1% (4/33) of children dying in their first five years.

Childhood onset

Childhood onset with predominantly motor delay and complex spastic-ataxia was identified in seven individuals in this study and those previously reported [2]. Case F1-III:1 has the least severe motor phenotype in our series (Supplementary S5). Case F8-II:1 has a phenotype resembling the previously reported cases with the c.121A>T mutation-severe spastic-ataxia but relatively preserved cognition [2]. The seven cases all achieved ambulation, though required walking aids (walking frame) 1 to 3 years into the disease and wheelchair 3 to 8 years later. Features including head titubation and severe dystonia in the previously reported patients who achieved adulthood, suggest that they may be related to disease progression rather than genotype.

Complex spastic-ataxia and developmental delay

The most common symptom at onset was nystagmus (25/33 cases) (Figure 4B) described as horizontal gaze-evoked, in the majority of cases. Other ocular manifestations were square wave jerks, hypometric saccades, impaired smooth pursuit and reduced visual acuities (4 cases). Limitation of bilateral, lateral gaze eye movements was seen later in three cases that reached adulthood.

Spasticity with brisk reflexes in the upper and lower limbs, and upgoing plantar responses were present in all cases. Axial hypotonia was reported at presentation in 9 patients, all with onset of disease before 1 year of age associated with upper and lower limb spasticity soon after presentation. Cervical and/or limb dystonia was present in around ~ 40% of cases where information was available. Examination of the peripheral nervous system was normal in all cases and normal nerve conduction studies were reported in two cases that reached adulthood.

Seizures were present in four (12.5%) patients harbouring NKX6–2 mutations. Case F1-III:1 presented primary tonic progressing to secondarily generalised seizure at six years. Electroencephalography at the age of 13 showed loss of age-based background activity and absent anterior-posterior gradient of background activity with focal tonic seizure presenting clinically as hemifacial seizures. There was intermittent frequency slowing, most pronounced at frontal electrodes and multifocal epileptic discharges (sharp waves and sharp-slow-waves) pronounced over the right hemisphere and several focal tonic seizures. The seizures were multi-drug resistant. No details regarding seizure phenomenology are available in the other three cases [3, 5].

Cognitive function varied greatly between patients. Interestingly, two cases reported here (F1-III:1 and F8-II:1) and four previously reported [2] (total 6/33) had normal cognitive development for their age. Case F8-II:1 and the four previously reported cases with normal cognitive development carry the homozygous nonsense mutation p.Lys41* while F1-III:1 carries two missense compound heterozygous variants (p.Arg101Ser; p.Leu181Val). However, severe cognitive impairment with arrested speech development was present in 66% of all children with bi-allelic NKX6–2 pathogenic variants and in all reported children with neonatal onset. We acknowledge that in most cases, an accurate cognitive function assessment was difficult due to severe motor impairment and/or developmental language delay.

Other features present in SPAX8 patients included strabismus (4/33 patients), scoliosis (6/33), neck or/and limb dystonia (9/23), contractures (4/33 patients), dysmorphism (2/33), hip dislocation (2/33) and single cases of hearing impairment and hirsutism.

Neuroimaging spectrum in NKX6–2-related disease

The key neuroimaging feature in the majority of cases was a hypomyelinating leukodystrophy. Magnetic resonance images (MRI) (Supplementary S6) showed signal abnormality with atrophy noted supratentorially within the thalami, and the globus pallidi. Infratentorially, there was notable involvement of the pons with signal abnormality involving the transverse pontine fibres with relative expansion to the entire pons. This contrasted with the orthogonal orientated fibres of the corticospinal tracts of relatively normal signal, providing a distinctive prominent appearance of the mid-pons on the axial T2-weighted sequences. Furthermore, signal change was noted in the cerebellar hemispheres, particularly involving the subcortical white matter (WM) and the dentate nuclei. Cerebellar volume was relatively increased in very young patients, likely related to the underlying WM changes, and demonstrated mild atrophic change over time. Not all children developed cerebellar atrophy (Supplementary S7).

Interestingly, in case F1-III:1 with two missense compound heterozygous mutations neuroimaging findings were milder compared to cases carrying homozygous truncation mutations (Figure 4C). Marked cerebellar atrophy was a key finding in this case. Furthermore, two other paediatric NKX6–2-related cases were reported previously without overt hypomyelination [4]. Thinning of the corpus calosum was present in 6/33 patients. A longitudinal MRI study in F7-II:3 at 4 and 8 years old shows progressive thinning of corpus callosum and cerebellar atrophy, associated with WM abnormality sparing the U fibers (Figure 4D).

DISCUSSION

Recently we described the first cases of NKX6–2 mutations leading to hypomyelination and spastic-ataxia phenotype in humans [2]. Given the rarity of hypomyelinating disorders and the absence of an unbiased cohort to screen, it is difficult to estimate the frequency of NKX6–2 mutations. However, genetic analysis of the UCL leukodystophies cohort identified 10 cases of hypomyelination with pathogenic mutations in PLP1 (four families), single cases of TUBB4A, POLR3A/B and CLCN2 [6]. Here we present six additional cases (three families) of hypomyelination due to NKX6–2 mutations from the same research group suggesting a more significant burden of NKX6–2 mutations.

We expanded the phenotypic spectrum and showed that NKX6–2 mutations lead to a neonatal onset at the severe end and childhood onset at the milder end. Interestingly, the compound heterozygous missense variants c.301C>A (p.Arg101Ser) and c.541C>G (p. Leu181Val) led to a significant reduction (>70%) of the NKX6–2 protein. It is possible that the small amount of NKX6–2 protein identified by western blot provided a degree of myelination leading to a less severe clinical picture. This individual and the three cases previously published [5] presented with multi-drug resistant epilepsy. In focal cortical dysplasia, a common cause of drug-resistant epilepsy, hypomyelination abnormality was confirmed in numerous histopathological epilepsy surgery specimen studies [7]. Focal dysplasia is currently linked to abnormalities in the differentiation of glial cells from their progenitors and their migration to the cortical place [8], a process regulated by transcription factors including NKX6–2 [9].

Additional clinical features associated with NKX6–2 mutations-cervical and/or limb dystonia, congenital abnormalities (congenital heart disease, undescended testes), severe dental and/or gum abnormalities -reflect the developmental role of NKX6–2 as a member of the homeobox gene family [10]. These genes are involved in the development, specifying geographical orientation of the body by directing the formation of limbs and organs [11]. Some homeobox genes such as PAX6 [12], OTX2 [13], and MEOX1 [14] were involved in a variety of developmental and neurological disorders with brain abnormalities.

Clinical and neuroimaging findings in NKX6–2-related disease reflect the involvement of WM and pyramidal tracts (spasticity, brisk reflexes, upgoing plantars), cerebellum (truncal and limb ataxia, nystagmus), and bulbar function (dysarthria, dysphagia). Complications related to these clinical manifestations led to significant impairment in vital functions including swallowing (although dysphagia was not routinely assessed in all cases, severe dysphagia requiring gastrostomy was reported in several cases), respiration and functionally disabling spasticity, similarly to other myelin-related diseases [15]. Early screening and recognition of these disease-related complications are important aspects during the clinical assessments of these patients.

Furthermore, our study expands the MRI spectrum of NKX6–2 mutations from diffuse hypomyelination to focal T2-weighted hyperintensity and parenchymal volume loss. Recently, other hypomyelinating leukodystrophy genes such as TUBB4A and POLR3A have been shown to have distinct phenotypes and neuroimaging spectrum, ranging from spastic paraplegia to spastic-ataxia without overt hypomyelination to hypomyelinating leukodystrophies resulting from different mutations [16, 17]. We identified a similar pattern in NKX6–2 with cases presenting clinically with spastic-ataxia in the absence of hypomyelination and a reduction of NKX6–2 protein levels (case F1-III:1) compared to extended hypomyelination in cases with truncating mutations resulting in no expression of NKX6–2 protein as previously reported [2]. Therefore, we highlight the importance of molecular diagnosis with additional functional work and confirmatory evidence.

In conclusion, we show that the phenotypic and neuroimaging expression in NKX6–2 mutations can range from a complex, neonatal onset at the severe end, a childhood onset at the milder end of the spectrum and that phenotypes with epilepsy in the absence of overt hypomyelination, and diffuse hypomyelination without seizures, can occur. We recommend that NXK6–2 should be included in hypomyelinating leukodystrophy and spastic-ataxia diagnostic panels.

Supplementary Material

Genotype-phenotype description all NKX6–2 mutations reported to date.

NA-not available, m-months, y-years, VEP-visual evoked potentials, ERG-electroretinogram, BAEP = brainstem auditory evoked potential, PDA=Patent Ductus Arteriosus.

Pathogenicity and novelty assessment of all NKX6–2 variants identified in this study.

Western blot analysis in individual F1-III:1. Experiments performed three times and three lysates from case and controls are shown on the blot.

Genotype-Phenotype description of the eight new families reported in this study.

Hypomyelination in NKX6–2-related disease. From left to right: multiple T1 weighted (column 1) and T2 weighted (columns 2–5) MRI acquisitions through four cases (top to bottom rows: F4-III:1, F3-II:1, F6-II:6, F2-II:1). Normal to hyperintense T1-white matter (WM) signal (column 1) in areas corresponding to the T2-weighted hyperintense signal (column 2) confirmed hypomyelination. Column 2 demonstrates diffuse T2 weighted hyperintense signal change in subcortical, deep WM including external capsules, globi pallidi and thalami. Columns 3 and 4 demonstrate dorsal mesencephalic and diffuse pontine T2 weighted hyperintense signal change. Column 5, demonstrates diffuse cerebellar WM T2 weighted hyperintense signal change including the peri-dentate WM with relative preservation of cerebellar volume.

Neuroimaging spectrum of NKX6–2-related disease.

Extended Methods.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the patients and their families for their essential help with this work. We are grateful to The Spastic Paraplegia Foundation and The UK HSP Society. This study was supported by the Medical Research Council (MRC UK MR/J004758/1, G0802760, G1001253), The Wellcome Trust in equipment and strategic award (Synaptopathies) funding (WT093205MA and WT104033/Z/14/Z), Ataxia UK, British Neurological Surveillance Unit (BNSU), the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). We also thank the Sequencing and Genotyping Core Facilities at KFSHRC for their technical help. N.K is supported by KACST Grant (14-MED2007–20) and KFSHRC seed grant (RAC#2120022). I.D receives support from the NIHR UCL/UCLH Biomedical Research Centre. Supported in part by Doris Duke Clinical Scientist Development Award 2014112 MCK and NIH NINDS NS083739 (MCK). M.A.S. was supported by the Deanship of Scientific Research, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia through the research group project number RGP-VPP-301.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures of all authors

Viorica Chelban -None

Maysoon Alsagob -None

Katja Kloth -None

Adela Chirita-Emandi -None

Jana Vandrovcova -None

Indran Davagnanam -None

Somayeh Bakhtiari -None

Moeenaldeen D. AlSayed -None

Zuhair Rahbeeni -None

Hamad AlZaidan -None

Nancy T. Malintan -None

Jessika Johannsen -None

Stephanie Efthymiou -None

Eloïse Tribollet -None

Kshitij Mankad -None

Saif A. Al-Shahrani -None

Mai AlShammariv -None

Stanislav Groppa-None

Nourelhoda A. Haridy -None

Laila AlQuait -None

Alya Qari -None

Rozeena Huma -None

Rawan Almass -None

Faten B Almutairi -None

Khushnooda Ramzan -None

Ibrahim A. Alorainy -None

Muddathir H. Hamad -None

Mustafa A. Salih -None

Faiqa Imtiaz -None

Maria Puiu -None

Michael C Kruer -None

Tatjana Bierhals -None

Nicholas W. Wood -None

Dilek Colak -None

Henry Houlden -None

Namik Kaya -None

Author roles:

(1) Research Project: A. Conception, B. Organization, C. Execution; (2) Statistical Analysis: A. Design, B. Execution, C. Review and Critique; (3) Manuscript Preparation: A. Writing of the First Draft, B. Review and Critique.

Viorica Chelban 1A, 1B, 1C, 2A, 2B, 3A

Maysoon Alsagob 1C, 2A, 2B, 3A

Katja Kloth 1C, 3B

Adela Chirita-Emandi 1C, 3B

Jana Vandrovcova 1C, 2B, 3B

Indran Davagnanam 1C, 3B

Somayeh Bakhtiari 1C, 3B

Moeenaldeen D. AlSayed 1C, 3B

Zuhair Rahbeeni 1C, 3B

Hamad AlZaidan 1C, 3B

Nancy T. Malintan 1C, 3B

Jessika Johannsen 1C, 3B

Stephanie Efthymiou 1C, 3B

Eloïse Tribollet 1C, 3B

Kshitij Mankad 1C, 3B

Saif A. Al-Shahrani 1C, 3B

Mai AlShammariv 1C, 3B

Stanislav Groppa 1C, 3B

Nourelhoda A. Haridy 1C, 3B

Laila AlQuait 1C, 3B

Alya Qari 1C, 3B

Rozeena Huma 1C, 3B

Rawan Almass 1C, 3B

Faten B Almutairi 1C, 3B

Khushnooda Ramzan 1C, 3B

Ibrahim A. Alorainy 1C, 3B

Muddathir H. Hamad 1C, 3B

Mustafa A. Salih 1C, 3B

Faiqa Imtiaz 1C, 3B

Maria Puiu 3B

Michael C Kruer 1C, 3B

Tatjana Bierhals 1C, 3B

Nicholas W. Wood 1A, 1C, 3B

Dilek Colak 3B

Henry Houlden 1A, 1B, 1C, 3B

Namik Kaya 1A, 1B, 1C, 3B

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

References:

- 1.Vanderver A., et al. , Whole exome sequencing in patients with white matter abnormalities. Ann Neurol, 2016. 79(6): p. 1031–1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chelban V., et al. , Mutations in NKX6–2 Cause Progressive Spastic Ataxia and Hypomyelination. Am J Hum Genet, 2017. 100(6): p. 969–977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dorboz I., et al. , Biallelic mutations in the homeodomain of NKX6–2 underlie a severe hypomyelinating leukodystrophy. Brain, 2017. 140(10): p. 2550–2556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anazi S., et al. , Expanding the genetic heterogeneity of intellectual disability. Hum Genet, 2017. 136(11–12): p. 1419–1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baldi C., et al. , Expanding the clinical and genetic spectra of NKX6–2-related disorder. Clin Genet, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lynch DS, et al. , Clinical and genetic characterization of leukoencephalopathies in adults. Brain, 2017. 140(5): p. 1204–1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blumcke I., et al. , The clinicopathologic spectrum of focal cortical dysplasias: a consensus classification proposed by an ad hoc Task Force of the ILAE Diagnostic Methods Commission. Epilepsia, 2011. 52(1): p. 158–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cepeda C., et al. , Epileptogenesis in pediatric cortical dysplasia: the dysmature cerebral developmental hypothesis. Epilepsy Behav, 2006. 9(2): p. 219–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Briscoe J., et al. , A homeodomain protein code specifies progenitor cell identity and neuronal fate in the ventral neural tube. Cell, 2000. 101(4): p. 435–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhong YF and Holland PW, The dynamics of vertebrate homeobox gene evolution: gain and loss of genes in mouse and human lineages. BMC Evol Biol, 2011. 11: p. 169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pearson JC, Lemons D., and McGinnis W., Modulating Hox gene functions during animal body patterning. Nat Rev Genet, 2005. 6(12): p. 893–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Azuma N., et al. , Mutations of the PAX6 gene detected in patients with a variety of optic-nerve malformations. Am J Hum Genet, 2003. 72(6): p. 1565–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ragge NK, et al. , Heterozygous mutations of OTX2 cause severe ocular malformations. Am J Hum Genet, 2005. 76(6): p. 1008–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mohamed JY, et al. , Mutations in MEOX1, encoding mesenchyme homeobox 1, cause Klippel-Feil anomaly. Am J Hum Genet, 2013. 92(1): p. 157–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Haren K., et al. , Consensus statement on preventive and symptomatic care of leukodystrophy patients. Mol Genet Metab, 2015. 114(4): p. 516–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Curiel J., et al. , TUBB4A mutations result in specific neuronal and oligodendrocytic defects that closely match clinically distinct phenotypes. Hum Mol Genet, 2017. 26(22): p. 4506–4518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.La Piana R., et al. , Diffuse hypomyelination is not obligate for POLR3-related disorders. Neurology, 2016. 86(17): p. 1622–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Genotype-phenotype description all NKX6–2 mutations reported to date.

NA-not available, m-months, y-years, VEP-visual evoked potentials, ERG-electroretinogram, BAEP = brainstem auditory evoked potential, PDA=Patent Ductus Arteriosus.

Pathogenicity and novelty assessment of all NKX6–2 variants identified in this study.

Western blot analysis in individual F1-III:1. Experiments performed three times and three lysates from case and controls are shown on the blot.

Genotype-Phenotype description of the eight new families reported in this study.

Hypomyelination in NKX6–2-related disease. From left to right: multiple T1 weighted (column 1) and T2 weighted (columns 2–5) MRI acquisitions through four cases (top to bottom rows: F4-III:1, F3-II:1, F6-II:6, F2-II:1). Normal to hyperintense T1-white matter (WM) signal (column 1) in areas corresponding to the T2-weighted hyperintense signal (column 2) confirmed hypomyelination. Column 2 demonstrates diffuse T2 weighted hyperintense signal change in subcortical, deep WM including external capsules, globi pallidi and thalami. Columns 3 and 4 demonstrate dorsal mesencephalic and diffuse pontine T2 weighted hyperintense signal change. Column 5, demonstrates diffuse cerebellar WM T2 weighted hyperintense signal change including the peri-dentate WM with relative preservation of cerebellar volume.

Neuroimaging spectrum of NKX6–2-related disease.

Extended Methods.