Abstract

Objective:

To examine whether military separation (Veteran), service component (active duty, Reserve/National Guard), and combat deployment, are prospectively associated with continuing unhealthy alcohol use among U.S. military Service members.

Methods:

Millennium Cohort Study participants were evaluated for continued or chronic unhealthy alcohol use, defined by screening positive at baseline and the next consecutive follow-up survey for heavy episodic, heavy weekly, or problem drinking. Participants meeting criteria for chronic unhealthy alcohol use were followed for up to 12 years to determine continued unhealthy use. Multivariable regression models—adjusted for demographics, military service factors, and behavioral and mental health characteristics—assessed whether separation status, service component, or combat deployment, were associated with continuation of 3 unhealthy drinking outcomes: heavy weekly (sample n = 2653), heavy episodic (sample n = 22,933), and problem (sample n = 2671) drinking.

Results:

In adjusted models, Veterans (compared with actively serving personnel) and Reserve/Guard (compared with active duty members) had a significantly higher likelihood of continued chronic use for heavy weekly, heavy episodic, and problem drinking (Veteran OR range 1.17–1.47; Reserve/Guard OR range 1.25–1.29). Deployers without combat experience were less likely than nondeployers to continue heavy weekly drinking (odds ratio [OR] 0.75, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.61–0.91).

Conclusions:

The elevated likelihood of continued unhealthy alcohol use among Veterans and Reserve/Guard members suggests that strategies to reduce unhealthy drinking targeted to these populations may be warranted.

Keywords: alcohol, drinking, military personnel, veteran health

INTRODUCTION

Unhealthy alcohol use, ranging from drinking above national recommended limits to meeting diagnostic criteria (Saitz 2005), among U.S. military personnel is common (Jacobson et al. 2008, Bray et al. 2013). Heavy episodic drinking—a particularly risky pattern of unhealthy alcohol use that elevates risk for alcohol use disorder (Saha et al. 2007)—is especially common among younger Service members (Jacobson et al. 2008, Bray et al. 2013). Further, alcohol use disorder with concurrent mental disorders is prevalent among U.S. Veterans (Fuehrlein et al. 2018). Although factors associated with unhealthy alcohol use among Service members and Veterans have been well described in cross-sectional analyses (Burnett-Zeigler et al. 2011), few studies have investigated the factors associated with continued, or chronic, unhealthy alcohol use over time.

Continued unhealthy alcohol use may have clinical and occupational implications due to subsequent impact on the risk of adverse outcomes associated with unhealthy alcohol use (e.g., degraded performance and medical outcomes (Shield et al. 2013, Bradley et al. 2016, Barai et al. 2017, Williams et al. 2018)). Given the inherent occupational demands and performance requirements faced by military personnel, it is particularly important to identify factors that may increase the risk of continued unhealthy alcohol use in this population.

Most military studies examining associations between Service member characteristics and unhealthy alcohol use employed cross-sectional designs (Mattiko et al. 2011, Bray et al. 2013, Clarke-Walper et al. 2014) and only one study assessed factors associated with relapse (Williams et al. 2015). Existing studies have highlighted service-specific characteristics that may increase risk for unhealthy alcohol use. Specifically, the DoD’s prospective Millennium Cohort Study of Service members and Veterans (Ryan et al. 2007) previously documented that combat deployment and being Reserve/National Guard were risk factors for both initiation and relapse of unhealthy alcohol use and that separation from military service was a risk factor for relapse (Jacobson et al. 2008, Williams et al. 2015). Other studies have shown a high proportion of unhealthy alcohol use among Reserve/Guard personnel (Milliken et al. 2007, Allison-Aipa et al. 2010) and Veterans (Calhoun et al. 2015, Fuehrlein et al. 2018). Further, population-based surveys administered to Active Duty military personnel showed increased rates of heavy and binge drinking over a 10-year period, with higher rates among combat-exposed personnel compared with non-combat exposed personnel (Bray et al. 2013), indicating that active duty combat deployers may be at risk for chronic drinking.

Though prior cross-sectional studies illuminate vulnerable populations of military personnel, longitudinal investigations are necessary for identifying modifiable military-specific factors associated with subsequent risk for continued unhealthy alcohol use among personnel initially screening positive. This report builds on two previous publications using Millennium Cohort data examining the initiation (Jacobson et al. 2008) and relapse (Williams et al. 2015) of unhealthy alcohol use, by examining military-specific factors associated with continued or chronic use, which has been very sparsely studied. By examining up to 12 years of Millennium Cohort follow-up survey data, including new data collected since the original study of relapse, this study aimed to build on its predecessors by examining military-specific factors associated with continued unhealthy alcohol use. Based on previous findings from this Cohort we hypothesized that military Veterans, those in the Reserve/Guard component, and those experiencing combat deployment would be more likely to continue heavy weekly, heavy episodic, or problem, drinking.

METHODS

Study Population and Data Sources

Data for this analysis were from the Millennium Cohort Study, which was launched in July 2001 and currently consists of 4 recruitment panels (enrolled in 2001, 2004, 2007, and 2011, respectively). Participants mainly served during the Operation Iraqi Freedom/Operation Enduring Freedom (OIF/OEF) conflicts. The Millennium Cohort Study protocol was approved by the Naval Health Research Center Institutional Review Board (protocol NHRC.2000.0007), and all enrolled members provided voluntary informed consent. Participants completed a baseline questionnaire upon enrollment with follow-up surveys completed in approximately 3–4 year intervals. Briefly, the initial enrollment panel (2001) was a cross-section of individuals serving in the military as of October 2000, oversampled for previous deployers to Southwest Asia, Bosnia, or Kosovo from 1998–2000, Reservists, and female Service members. Subsequent enrollment panels followed the same general methodology but were sampled from newer military accessions having served 1 to 5 years when the sampling frame was obtained. Additional details regarding the sampling and methodology have been published elsewhere (Ryan et al. 2007).

Inclusion Criteria

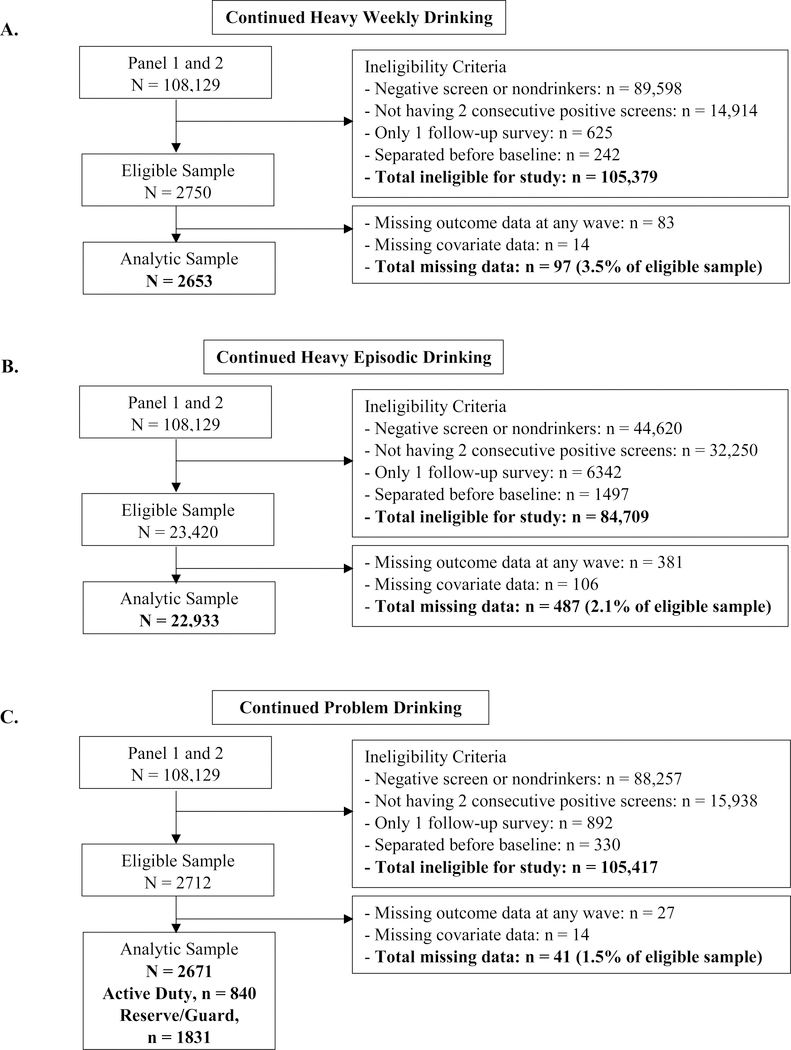

A minimum of three completed surveys were necessary for inclusion in this study. The first two surveys were used to determine persons previously meeting criteria for each of three patterns of unhealthy alcohol use (heavy weekly drinking, heavy episodic drinking, and problem drinking; defined below), and the final survey was used to assess whether a participant reported continued unhealthy use. These criteria were implemented to avoid capturing fluctuating behaviors for these potentially dynamic outcomes. A distinct subsample for each outcome was created for analyses. Only participants who screened positive for the outcome at baseline and the next consecutive survey, completed at least 3 surveys, and were serving in the military at baseline were eligible for analyses. A total of 2653 subjects met eligibility criteria for the heavy weekly drinking sample, 22,933 for the heavy episodic drinking sample, and 2671 for the problem drinking sample. Among eligible individuals, only 1.5% to 3.7% were excluded for missing data (see flowcharts for Figure 1A–C).

Figure 1.

Flow charts detailing the sample selection for each unhealthy drinking outcome. A – Continued Heavy Weekly Drinking; B – Continued Heavy Episodic Drinking; and C – Continued Problem Drinking.

Measures

Chronic and Continued Unhealthy Alcohol Use

Three patterns of unhealthy alcohol use were measured to define each subsample and determine continuation of each outcome by at least the third completed survey. Unhealthy alcohol use was defined using responses to 3 questions from the Millennium Cohort survey: (1) the number of drinks a participant reported consuming on each day of the past week, (2) the number of days in the past year a participant reported drinking ≥5 alcoholic drinks, and (3) the 5-item alcohol module from the PRIME-MD Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) (Spitzer et al. 1999), designed to assesses consequences happening more than once in the last 12 months associated with alcohol use. Heavy weekly drinking was derived from the self-reported total number of drinks consumed on each day of the past week, with a weekly threshold of >14 drinks for men and >7 drinks for women (Dawson et al. 2005, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2005). Heavy episodic drinking was defined as self-reported consumption of ≥5 drinks for men or ≥4 drinks for women on at least 1 day of the past week or “drinking ≥5 alcoholic beverages” on at least 1 day or occasion during the past year (Naimi et al. 2003, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2005). This measure was used because research suggests that report of any past-year heavy episodic drinking is associated with increased risk for alcohol use disorder and may be suitable for inclusion in diagnostic criteria for alcohol use disorder (Saha et al. 2007). Problem drinking was defined as endorsement of at least 1 of the following 5 items from the PHQ alcohol module happening more than once in the last 12 months: (1) drinking alcohol even though a physician suggested to stop drinking due to health problems; (2) drinking, being high, or being hungover from alcohol while working, going to school, or taking care of children or other responsibilities; (3) being late or missing work, school, or other activities because of drinking or being hungover; (4) having a problem getting along with people while drinking; or (5) driving a car after having several drinks or drinking too much (Jacobson et al. 2008). These dichotomous outcomes were measured at each study time point.

Main Exposures of Interest

Separation from military service, component status, and combat deployment, were the main exposures of interest. Separation from military service (Veteran status) was provided by the Defense Manpower Data (DMDC). Separation dates were used to determine whether a subject parted from service any time between their baseline survey and their most recent survey when the outcome was measured.

Component status (active duty or Reserve/Guard) was also provided by DMDC. Each participant’s status was updated to reflect their component at the time when they filled out their survey preceding their most recent survey when the outcome was measured.

Deployment dates were provided by DMDC and self-report of combat exposures was assessed at each follow-up based on at least one affirmative response to witnessing any of the following: (1) a person’s death due to war, disaster, or tragic event; (2) instances of physical abuse; (3) dead or decomposing bodies; (4) maimed soldiers or civilians; or (5) prisoners of war or refugees (Porter et al. 2018). At each subsequent follow-up survey, participants were asked whether these experiences had occurred in “the last 3 years”; thus, reports of experiences could be linked with deployments occurring during the same 3-year interval.

Covariates

Several covariates were measured due to their potential to influence changes in alcohol use over time. The following covariates were assessed at baseline and held constant throughout the follow-up period, since they were unlikely to change significantly during follow-up: sex; birth year; race/ethnicity; education level; service branch; military occupation; deployment to southwest Asia, Bosnia, or Kosovo prior to baseline (panel 1 only); and combat deployment prior to baseline. Covariates that were likely to change over time were assessed at the survey prior to outcome determination (most recent survey), including pay grade; marital status; screening status for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), determined using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition criteria for the PTSD Checklist–Civilian Version (report of moderate or higher level of at least 1 intrusion symptoms, 3 avoidance symptoms, and 2 hyperarousal symptoms) (Blanchard et al. 1996); screening status for depression, determined using the PHQ-8 (5 or more of the 8 depressive symptoms were reported on “more than half the days” or “nearly every day” in the past 2 weeks, and 1 of the symptoms is depressed mood or anhedonia) (Kroenke et al. 2009); smoking status; report of sexual assault (yes or no); and life stressors (none, 1, or >1), determined using a modified Holmes and Rahe scale (Holmes and Rahe 1967).

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive analyses were completed to examine bivariate relationships between each of the 3 drinking outcomes and the 3 main exposures, as well as other measured factors. This included the calculation of the proportion of continued unhealthy alcohol use for each outcome within strata of the main exposures of interest and covariates, using Chi-square test statistics. The Bonferroni correction method was applied to reduce the risk for Type I error given the 48 multiple comparisons made for each alcohol outcome, which adjusted the threshold for statistical significance from 0.05 to 0.001 (Armstrong 2014).

Generalized estimating equation (GEE) models were fit to the longitudinal data to estimate the odds of subsequent continuation of heavy episodic, heavy weekly, and problem drinking, in relation to the 3 main exposures (service component, combat deployment, and separation from military service). The GEE model framework allows participants to have multiple rows of data representing each follow-up data point, accounting for the correlation of within-subject data. Approximately 3 years passed between each follow-up, and the models were adjusted for the time between follow-ups. Participants that continued each pattern of unhealthy alcohol use were included in models until follow-up time ended. The models were adjusted for all characteristics that were oversampled in the original study sample (sex, prior deployment), as well as demographics (race/ethnicity, age, marital status, and education), military service characteristics (combat deployment prior to baseline, combat deployment during follow-up, service branch, occupation, and pay grade), and behavioral characteristics (smoking status, screening status for PTSD and depression, life stressors, and sexual assault).

Collinearity among independent variables was assessed using variance inflation factors: factors of 4 or greater indicated the presence of collinearity (Harrell et al. 1996). Given previous findings of significant differences in unhealthy alcohol use by component status, we tested for an interaction between service component and combat deployment for each of the 3 outcomes and used an alpha level of P ≤ 0.10 (Jewell 2004), and stratified results for outcomes where a significant interaction was detected.

RESULTS

Descriptive Results (Table 1)

Table 1.

Frequencies and Proportions of Continued Unhealthy Alcohol Use, by Subgroup Characteristics

| Samples with Two Sequential Positive Screens for Each Pattern of Unhealthy Alcohol Use* | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Heavy Weekly Drinking Sample (N=2653) |

Respondents with Continued Heavy Weekly Drinking n = 1631 |

Heavy Episodic Drinking Sample (N=22,933) |

Respondents with Continued Heavy Episodic Drinking n=17,017 |

Problem Drinking Sample (N=2671) |

Respondents with Continued Problem Drinking n=1537 |

|||

| n | % | p- value** |

n | % | p- value** |

n | % | p- value** |

|

| Main Exposures | |||||||||

| Veteran status | 0.28 | 0.65 | <.0001 | ||||||

| Actively serving | 1728 | 60.9 | 15695 | 74.2 | 1750 | 54.7 | |||

| Separated during follow-up | 925 | 63.0 | 7238 | 74.5 | 921 | 63.1 | |||

| Service component | <0.01 | <.0001 | 0.02 | ||||||

| Active duty | 1019 | 58.0 | 12057 | 72.5 | 840 | 54.2 | |||

| Reserve/National Guard | 1634 | 63.8 | 10876 | 76.0 | 1831 | 59.2 | |||

| Combat deployment during follow-up | <.0001 | <0.01 | 0.09 | ||||||

| Not deployed | 1438 | 66.3a | 10026 | 73.6 a | 1277 | 59.1 a | |||

| Deployed, no combat | 462 | 56.3b | 5231 | 73.3 a | 480 | 53.3 a | |||

| Deployed, with combat | 753 | 55.9b | 7676 | 76.0b | 914 | 57.8a | |||

| Demographic variables | |||||||||

| Sex | 0.85 | <.0001 | 0.28 | ||||||

| Male | 1914 | 61.6 | 18723 | 76.6 | 2191 | 58.1 | |||

| Female | 739 | 61.3 | 4210 | 64.3 | 480 | 55.4 | |||

| Birth year | <.0001 | <0.01 | 0.47 | ||||||

| Pre-1960 | 678 | 72.0 a | 3108 | 72.7 a | 377 | 61.2 a | |||

| 1960–1969 | 863 | 66.6 a | 7642 | 73.3 a | 692 | 56.2 a | |||

| 1970–1979 | 768 | 54.0 b | 8598 | 75.7 b,c | 989 | 57.5 a | |||

| 1980 + | 344 | 44.5 b | 3585 | 74.7 a,c | 613 | 57.2 a | |||

| Race/ethnicity | 0.06 | <.0001 | 0.84 | ||||||

| White | 2274 | 62.5 a | 18888 | 75.1 a | 2205 | 57.9 a | |||

| Black | 150 | 56.0 a | 1436 | 65.9 b | 172 | 55.9 a | |||

| Other | 229 | 55.5 a | 2609 | 73.8 a | 294 | 56.8 a | |||

| Marital status | <.0001 | <.0001 | 0.47 | ||||||

| Never married | 659 | 54.8 a | 5016 | 77.1 a | 923 | 57.7 a | |||

| Married | 1562 | 64.7 b | 14723 | 74.0 b | 1292 | 56.7 a | |||

| No longer married | 432 | 60.6 a, b | 3194 | 71.4 b | 456 | 60.0 a | |||

| Education level | 0.02 | <.0001 | 0.51 | ||||||

| High school/GED or less | 489 | 57.2 a | 3995 | 77.0 a | 548 | 59.7 a | |||

| Some college, no degree | 1004 | 60.7 a | 9293 | 74.2 b | 1152 | 57.4 a | |||

| Associate / Bachelor’s / Master’ degree | 1160 | 64.2 a | 9645 | 73.4 b | 971 | 56.7 a | |||

| Military variables | |||||||||

| Pay grade | <0.01 | 0.28 | 0.11 | ||||||

| Enlisted | 1980 | 59.7 | 17161 | 74.5 | 2205 | 58.3 | |||

| Officer | 673 | 67.1 | 5772 | 73.8 | 466 | 54.3 | |||

| Service branch | 0.61 | <.0001 | 0.11 | ||||||

| Army | 1306 | 61.9 a | 10693 | 74.7 a | 1425 | 57.7 a | |||

| Navy/Coast Guard | 512 | 62.3 a | 4405 | 74.8 a | 496 | 55.6 a | |||

| Marine Corps | 186 | 57.0 a | 1472 | 83.6 b | 270 | 64.1 a | |||

| Air Force | 649 | 61.7 a | 6363 | 71.2 c | 480 | 55.8 a | |||

| Military occupation | 0.40 | <.0001 | 0.28 | ||||||

| Combat | 562 | 62.0 a | 5150 | 77.1 a | 626 | 55.8 a | |||

| Healthcare | 260 | 65.3 a | 1941 | 71.7 b | 231 | 54.6 a | |||

| Other | 1831 | 60.9 a | 15842 | 73.8 b | 1814 | 58.6 a | |||

| Deployment prior to baseline to SW Asia, Bosnia, or Kosovo | 0.93 | 0.24 | 0.04 | ||||||

| No | 1983 | 61.6 | 16482 | 74.1 | 2132 | 56.6 | |||

| Yes | 670 | 61.7 | 6451 | 74.9 | 539 | 61.6 | |||

| Combat deployment prior to baseline | <0.01 | 0.22 | 0.87 | ||||||

| Not deployed | 2364 | 62.9 a | 19955 | 74.2 a | 2251 | 57.6 a | |||

| Deployed, no combat | 92 | 54.4 a,c | 1094 | 73.5 a | 110 | 55.5 a | |||

| Deployed, with combat | 197 | 49.2b,c | 1884 | 75.9 a | 310 | 58.4 a | |||

| Behavioral variables | |||||||||

| Positive screen for mental health disorders | <.0001 | 0.02 | 0.10 | ||||||

| None | 2016 | 61.6 a | 18952 | 74.7 a | 1792 | 56.6 a | |||

| PTSD only | 138 | 58.7 a,b | 929 | 74.6 a | 193 | 60.1 a | |||

| Depression only | 273 | 71.7 b | 1701 | 71.7 a | 301 | 55.3 a | |||

| PTSD and depression | 226 | 51.6 a | 1351 | 72.5 a | 385 | 62.9 a | |||

| Sexual assault | 0.75 | <.0001 | 0.93 | ||||||

| No | 2410 | 61.5 | 21561 | 74.8 | 2439 | 57.6 | |||

| Yes | 243 | 62.6 | 1372 | 66.6 | 232 | 57.3 | |||

| Smoking status | 0.69 | <.0001 | <0.01 | ||||||

| Never smoker | 899 | 62.7 a | 10805 | 72.1 a | 1040 | 52.8 a | |||

| Former smoker | 969 | 61.1 a | 7187 | 76.2 b | 865 | 60.1 b | |||

| Current smoker | 785 | 61.0 a | 4941 | 76.6 b | 766 | 61.3 b | |||

| Life stressors | 0.09 | 0.25 | 0.01 | ||||||

| None | 1901 | 61.6 a | 17107 | 74.2 a | 1765 | 55.6 a | |||

| 1 | 547 | 63.9 a | 4505 | 74.3 a | 641 | 61.9 a | |||

| >1 | 205 | 55.1 a | 1321 | 76.3 a | 265 | 60.6 a | |||

Participants were followed for up to 12 years after chronic unhealthy drinking was established. Subjects were evaluated for screening positive for alcohol misuse after screening positive for a given outcome for at least 2 consecutive survey assessments.

Group differences were evaluated using the Chi-square test statistic, and associated p-values were adjusted for the 48 multiple comparisons made for each outcome using the Bonferroni correction method. The Bonferroni correction adjusted the significance threshold to p < 0.001, which are indicated with bold type. Percentages with different superscripts were significantly different from one another at p < 0.001(multilevel variables only).

GED, general equivalency diploma; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; SW, Southwest.

The overall proportions of continued unhealthy alcohol use were as follows: 61.4% for heavy weekly drinking (n = 1631); 74.2% for heavy episodic drinking (n = 17,017); and 57.5% for problem drinking (n = 1537). A significantly greater proportion of Veterans (compared with actively serving personnel) reported continued problem drinking (p < 0.001), while a significantly greater proportion of Reserve/Guard personnel (compared with active duty) reported heavy episodic drinking (p < 0.001). Participants who did not deploy during follow-up had the highest prevalence of continued heavy weekly drinking while those deployed with combat had a significantly higher prevalence of continued heavy episodic drinking compared with those deployed without combat and those not deployed.

Other factors significantly associated with continued heavy weekly drinking included older age, being married, having no deployments prior to baseline, and screening positive for depression. Factors significantly associated with continued heavy episodic drinking included male sex, younger age, White race/ethnicity, having never been married, having less education, being in the Marine Corps, having a combat-related occupation, having no self-report of sexual assault, and being a former or current smoker. Former or current smoking was the only additional factor significantly related to continued problem.

Multivariable Model Results

Collinearity and Interaction Testing

None of the independent variables were found to be collinear. A marginally significant interaction between combat deployment and service component was identified for the problem drinking outcome only (P = 0.10). The associations between combat deployment and continued problem drinking stratified by active duty and Reserve/Guard status are presented in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Adjusted* Odds Ratios (ORs) for Continued Problem Drinking Over Follow-up† Among Participants Who Initially Screened Positive for 2 Consecutive Assessments, Stratified by Service Component

| Adjusted Odds for Continued Problem Drinking |

||

|---|---|---|

| Active Duty (N = 840) |

Reserve/National Guard (N = 1831) |

|

| Characteristic | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) |

| Veteran status | ||

| Actively serving | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Separated during follow-up | 1.87 (1.40–2.50) | 1.36 (1.10–1.68) |

| Combat deployment during follow-up | ||

| Not deployed | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Deployed, no combat | 0.81 (0.56–1.18) | 0.92 (0.72–1.17) |

| Deployed, with combat | 1.44 (1.01–2.04) | 0.95 (0.77–1.18) |

Bold values indicate statistically significant ORs.

The model results presented were adjusted for the following variables: sex; birth year; race/ethnicity; marital status; education level; pay grade; service branch; deployment to Southwest Asia, Bosnia, or Kosovo from 1998–2000; deployment prior to baseline to operations in Iraq or Afghanistan; screening status for posttraumatic stress disorder or depression; report of sexual assault; smoking status; and report of life stressors.

Participants were followed for up to 12 years after chronic unhealthy drinking was established.

CI, confidence interval.

Continued Heavy Weekly Drinking

In models adjusted for all measured factors, Veterans (vs actively serving members) and Reserve/Guard members (vs active duty) were significantly more likely to continue heavy weekly drinking (Veterans, OR 1.35, 95% CI 1.15–1.60; Reserve/Guard, OR 1.26, 95% CI 1.07–1.50; Table 2). Service members with recent deployment history were less likely to continue heavy weekly drinking (deployed with combat, OR 0.85, 95% CI 0.70–1.03; deployed without combat, RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.61–0.91) compared with those with no deployment; however, only the deployed without combat group was significantly different.

TABLE 2.

Adjusted* Odds Ratios (ORs) for Continued Unhealthy Alcohol Use Over Follow-up† Among Participants Who Initially Screened Positive for 2 Consecutive Assessments

| Adjusted Odds for Continued Heavy Weekly Drinking (N = 2635) |

Adjusted Odds for Continued Heavy Episodic Drinking (N = 22,933) |

Adjusted Odds for Continued Problem Drinking (N = 2671) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) |

| Main exposures of interest | |||

| Veteran status | |||

| Actively serving | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Separated during follow-up | 1.35 (1.15–1.60) | 1.17 (1.10–1.25) | 1.47 (1.25–1.72) |

| Service component | |||

| Active duty | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Reserve/National Guard | 1.26 (1.07–1.50) | 1.25 (1.18–1.32) | 1.29 (1.10–1.52) |

| Combat deployment during follow-up | |||

| Not deployed | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Deployed, no combat | 0.75 (0.61–0.91) | 0.97 (0.91–1.05) | 0.89 (0.72–1.08) |

| Deployed, with combat | 0.85 (0.70–1.03) | 1.05 (0.99–1.13) | 1.06 (0.88–1.27) |

Bold values indicate statistically significant ORs.

The model results presented were adjusted for the following variables: sex; birth year; race/ethnicity; marital status; education level; pay grade; service branch; deployment to Southwest Asia, Bosnia, or Kosovo from 1998–2000; deployment prior to baseline to operations in Iraq or Afghanistan; screening status for posttraumatic stress disorder or depression; report of sexual assault; smoking status; and report of life stressors.

Participants were followed for up to 12 years after chronic unhealthy drinking was established.

CI, confidence interval.

Continued Heavy Episodic Drinking

Both Veterans (vs actively serving members) and Reserve/Guard members (vs active duty) were significantly more likely to continue heavy episodic drinking (Veterans, OR 1.17, 95% CI 1.10–1.25; Reserve/Guard, OR 1.25, 95% CI 1.18–1.32).Combat deployment was not significantly associated with continued heavy episodic drinking.

Continued Problem Drinking

Both Veterans (vs actively serving members) and Reserve/Guard members (vs active duty) were more likely to continue problem drinking (Veterans, OR 1.47, 95% CI 1.25–1.72; Reserve/Guard, OR 1.29, 95% CI 1.10–1.52). Combat deployment was not significantly associated with continued problem drinking (Table 2). In models stratified by component status (Table 3) there was a significant association between combat deployment and continued problem drinking among Active Duty participants only (OR 1.44, 95% CI 1.01–2.04). Associations with Veteran status remained in the same direction, where Veterans were more likely to continue problem drinking compared with actively serving participants, but associations were stronger for active duty (OR 1.87, 95% CI 1.40–2.50) than Reserve/Guard (OR 1.36, 95% CI 1.10–1.68) (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

The present study found that Veterans and Reserve/Guard members had a higher likelihood of continued unhealthy alcohol use across all three outcomes, while deployment without combat experience was associated with a lower likelihood of continuing heavy weekly drinking, and deployment with combat experience was associated with a higher likelihood of continued problem drinking among active duty personnel. Deployers may face unique stressors if exposed to combat; Reserve/Guard members may experience consequences of inadequate training for certain missions, or difficulties with reintegration; and Veterans may experience stress during and after separation, or may feel more freedom to imbibe post-separation. An Institute of Medicine (IOM) report (page 6) stated that “levels of alcohol and other drug use in the military are a public health crisis” and identified unmet treatment and services needs in current and former Reserve and National Guard members and Veterans with other than honorable discharge (Institute of Medicine, 2012). These subgroups often have less access to care in the Veterans Health Administration (VA), a setting that may offer evidence-based, alcohol-related services at higher rates than other healthcare settings (Moyer and Finney 2010, Williams et al. 2011, Bachrach et al. 2018).

One key finding from this study is that Veteran status was associated with a higher likelihood for continuation of all three patterns of unhealthy alcohol use, even after inclusion and adjustment for factors highly associated with substance use (e.g., PTSD, depression, sexual trauma status, and military combat deployment) (Clarke-Walper et al. 2014). All study participants were in military service at baseline, and approximately 31% separated from service during follow-up across the 3 study populations combined (12% from baseline to follow-up 1; 12% from follow-up 2 to follow-up 3; and 7% from follow-up 3 to follow-up 4). Studies have shown that separation from service may be a time when negative outcomes occur, such as the development of mental health disorders (Brignone et al. 2017), weight gain (Littman et al. 2013) and substance use (Derefinko et al. 2018).

The transition out of military service may increase stress given the likely need to find new employment and/or education, housing, and social circles, all while potentially continuing to provide for one’s self or family. Stress from changes in life circumstances has been linked with alcohol use (Keyes et al. 2011). Resultantly, unhealthy behaviors may continue post-separation, potentially as coping mechanisms for adapting to a new lifestyle. Although a recent study reported that many Veterans are being screened for alcohol use and receiving advice regarding alcohol’s adverse health effects from a physician (Bachrach et al. 2018), this study also found that Veterans were not more likely to be given explicit advise to reduce or abstain from drinking, a key element of an evidence-based brief intervention (Whitlock et al. 2004), which may contribute to the continuation of unhealthy drinking in Veterans.

Reserve/Guard personnel were more likely than active duty to continue all three patterns of unhealthy alcohol use. Higher levels of pre-deployment preparedness and unit support are associated with a lower likelihood of post-deployment unhealthy alcohol use, suggesting the training for deployment roles that is critical to post-deployment success may not always be sufficient for Reserve/Guard members (Orr et al. 2014). In addition, Reserve/Guard members must reintegrate into their communities after deployment and may not encounter appropriate post-deployment support (Goldmann et al. 2012) or have adequate access to services (Gorman et al. 2011). Finally, access to VA services varies for Reserve/Guard members, depending on criteria like the amount of time served and duty status (U.S. Department of Veteran’s Affairs, Office of Public and Intergovernmental Affairs, 2018), such that many members may not receive the services they need (Institute of Medicine, 2013).

We observed that Service members with deployment history were less likely than those who did not deploy to continue heavy weekly drinking; although the association was only statistically significant for deployers without combat experience. These findings, divergent from those reporting higher risk for initiation for the same alcohol outcomes among combat deployers in our 2008 report (Jacobson et al. 2008), may be due to the fact that future behavior is guided by past behavior and habits tend to exist in a stable context (Ouellette and Wood 1998). While a negative deployment-related experience like combat stress may be sufficient to initiate a new behavior, the experience of one or multiple deployments may not be supportive of chronic unhealthy alcohol use, given the unstable environment and the practicality issue (lack of access to alcohol while deployed).

Reasons why deployers may have been less likely to continue heavy weekly drinking in this study are that some deployers may have needed to drink regularly to cope with deployment experiences, and no longer needed this coping strategy after a longer period home from deployment. It is also possible that for the 40% of the sample that deployed more than once (data not shown), the cumulative time deployed, and thereby cumulative time with limited or no access to alcohol, coupled with the rigors of deployment and remaining deployable, may lead people away from this pattern of unhealthy alcohol use. Some evidence of this is also suggested by the conflicting findings that deployers were less likely than nondeployers to continue heavy weekly drinking, but combat deployers were more likely than nondeployers to continue problem drinking, among Active Duty personnel. This may have been due to the high-risk behavior measured by the problem drinking outcome (e.g. driving a car after drinking too much), and high risk behaviors have been reported to persist post-deployment in other studies (Woodall et al. 2014).

This study had limitations. Despite the comprehensive sampling frame, the Millennium Cohort Study may not be fully representative of the entire military or Veteran populations. Issues of generalizability may also be related to non-response to follow-up questionnaires. The survey was administered approximately every three years, and not all participants responded to each follow-up. It is possible that changes in drinking habits could have avoided detection by occurring within the interval between surveys and use resumed by the time of the next survey. Nonresponse bias has been investigated among participants from the first enrollment panel, revealing that heavy drinking was associated with lower likelihood of response (Littman et al. 2010). Participants may be prone to recall error when reporting alcohol use in the past week and during the past year (Dawson 2003). Also, no assessment of diagnostic criteria for alcohol use disorders was included in the surveys, nor were measures of previous treatment history for alcohol use disorders available. Nonetheless, these findings are generalizable to current Service members and recent Veterans who began unhealthy drinking behavior while still on active service.

Despite these limitations, strengths of this analysis include follow-up time for participants of up to 12 years, making this one of the only longitudinal studies of a military population tracking the same individuals for this length of time while measuring continued unhealthy alcohol use. In addition, the examination of 3 different alcohol outcomes allowed for a more complete picture of chronic drinking behavior in this military population. With 2 panels of subjects included in this study, the relatively large size and heterogeneity of the sample with respect to age, military status, and other factors enabled adjustment for confounding, exploration of effect modification, and examination of chronic alcohol misuse over the military-life course.

CONCLUSIONS

This study observed that both Reserve/Guard members and OIF/OEF Veterans were more likely to continue unhealthy drinking behavior across all three dimensions of alcohol misuse. Our prospective Millennium Cohort study findings, when coupled with those of Jacobson and Williams, provides the DoD and VA medical systems with screening criteria for identifying chronic unhealthy alcohol use, as well as risk factors associated with relapse to, or initiation of alcohol use. The VA has been a leader among healthcare systems in integrating evidence-based alcohol-related care (Moyer and Finney 2010, Williams et al. 2011, Gordon 2018) —including routine alcohol screening, brief interventions for patients screening positive for unhealthy alcohol use, and clinical guidelines recommending behavioral and pharmacological treatments for alcohol use disorders guided by shared decision making (The Management of Substance Use Disorders Work Group, 2015). However, the VA could employ strategies for improved recruitment and retention of Veterans such as reducing barriers to utilization (e.g. better explanation about VA benefits eligibility and improved patient satisfaction) (Damron-Rodriguez et al. 2004), implementing evidence-based brief interventions offering explicit advice (Whitlock et al. 2004), and offering treatments in a patient-centered way for those with more severe and chronic unhealthy alcohol use (i.e., more than 70% of all eligible participants in our study across patterns of unhealthy alcohol use). The DoD could also continue to focus resources on screening returning combat deployers for substance use and should work to reduce organizational barriers for seeking care (Kim et al. 2016) and identify effective treatments. Potential treatment options include behavioral (e.g., cognitive behavioral therapy) and/or pharmacologic interventions (e.g., FDA-approved medications to treat AUD). Given that unhealthy alcohol use coupled with its negative consequences leads to diminished force readiness, medical morbidity and mortality, and increased spending for medical and legal costs, continued focus on integrative screening and treatment approaches remains critical for the DoD and VA.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Disclaimer: Some authors are employees of the US Government. This work was prepared as part of their official duties. Title 17, U.S.C. §105 provides that copyright protection under this title is not available for any work of the U.S. Government. Title 17, U.S.C. §101 defines a U.S. Government work as work prepared by a military service member or employee of the U.S. Government as part of that person’s official duties.

Report No. 19–115 was supported by the Defense Health Program, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development, and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Patient Care Services under work unit no. 60002. The funder had no part in the study design, collection of the data, analysis of the data, or writing of manuscript.

The study protocol was approved by the Naval Health Research Center Institutional Review Board in compliance with all applicable Federal regulations governing the protection of human subjects. Research data were derived from an approved Naval Health Research Center, Institutional Review Board protocol number NHRC.2000.0007.

In addition to the authors, the Millennium Cohort Study Team includes Richard Armenta, PhD; Satbir Boparai, MBA; Felicia Carey, PhD; Toni Rose Geronimo-Hara, MPH; Claire Kolaja, MPH; Cynthia LeardMann, MPH; Rayna Matsuno, PhD; Deanne Millard; Chiping Nieh, PhD; Teresa Powell, MS; Ben Porter, PhD; Anna Rivera, MPH; Beverly Sheppard; Daniel Trone, PhD; Jennifer Walstrom; and Steven Warner, MPH. The authors also appreciate contributions from the Deployment Health Research Department, Millennium Cohort Family Study Team, Birth and Infant Health Research Team, and Henry M. Jackson Foundation. We greatly appreciate the contributions of the Millennium Cohort Study participants.

Role of Funding Source

This work was supported in part by Merit Review, Award ZDA1–04-W10 from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Clinical Science Research and Development service. Dr. Williams was supported by a Career Development Award from the Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development (CDA 12–276). The Department of Veterans Affairs Puget Sound supported Dr. Boyko’s involvement in this research. The Millennium Cohort Study is funded through the Defense Health Program and the Military Operational Medicine Research Program of the U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command, Fort Detrick, MD, and the U.S. Navy Bureau of Medicine and Surgery under work unit 60002.

Ethical Approval

This research has been conducted in compliance with all applicable federal regulations governing the protection of human subjects in research (Protocol NHRC.2000.0007).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

REFERENCES

- 1.Substance Use in the U.S. Armed Forces Retrieved from: http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2012/Substance-Use-Disorders-in-the-US-Armed-Forces.aspx. In: Institute of Medicine, Institute of Medicine, 2012. Accessed November 9, 2018.

- 2.Returning home from Iraq and Afghanistan: Assessment of readjustment needs of veterans, service members and their families Available at http://nap.edu/13499. Accesssed December 2, 2015 In: Institute of Medicine, 2013.

- 3.Helping Patients Who Drink Too Much: A Clinician’s Guide, Updated 2005 Edition U. S. Department of Health & Human Services. National Institutes of Health. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Available at: https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/sites/default/files/publications/guide.pdf Accessed: March 12, 2019.

- 4.VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Substance Use Disorders Available at: https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/sud/VADoDSUDCPGRevised22216.pdf The Management of Substance Use Disorders Work Group, 2015. Accessed June 28, 2019.

- 5.Federal Benefits for Veterans, Dependents and Survivors, Chapter 9 Reserve and National Guard, Eligibility for VA Benefits Retrieved from: https://www.va.gov/opa/publications/benefits_book/benefits_chap09.asp U.S. Department of Veteran’s Affairs, Office of Public and Intergovernmental Affairs, 2018. Accessed November 9, 2018.

- 6.Allison-Aipa TS, Ritter C, Sikes P, Ball S. The impact of deployment on the psychological health status, level of alcohol consumption, and use of psychological health resources of postdeployed U.S. Army Reserve soldiers. Mil Med 2010;175:630–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Armstrong RA. When to use the Bonferroni correction. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 2014;34:502–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bachrach RL, Blosnich JR, Williams EC. Alcohol screening and brief intervention in a representative sample of veterans receiving primary care services. Journal of substance abuse treatment 2018;95:18–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barai N, Monroe A, Lesko C, et al. The Association Between Changes in Alcohol Use and Changes in Antiretroviral Therapy Adherence and Viral Suppression Among Women Living with HIV. AIDS and behavior 2017;21:1836–1845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blanchard EB, Jones-Alexander J, Buckley TC, Forneris CA. Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist (PCL). Behav Res Ther 1996;34:669–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bradley KA, Rubinsky AD, Lapham GT, et al. Predictive validity of clinical AUDIT-C alcohol screening scores and changes in scores for three objective alcohol-related outcomes in a Veterans Affairs population. Addiction (Abingdon, England) 2016;111:1975–1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bray RM, Brown JM, Williams J. Trends in binge and heavy drinking, alcohol-related problems, and combat exposure in the U.S. military. Substance use & misuse 2013;48:799–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brignone E, Fargo JD, Blais RK, Carter ME, Samore MH, Gundlapalli AV. Non-routine Discharge From Military Service: Mental Illness, Substance Use Disorders, and Suicidality. Am J Prev Med 2017;52:557–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burnett-Zeigler I, Ilgen M, Valenstein M, et al. Prevalence and correlates of alcohol misuse among returning Afghanistan and Iraq veterans. Addict Behav 2011;36:801–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Calhoun PS, Schry AR, Wagner HR, et al. The prevalence of binge drinking and receipt of provider drinking advice among US veterans with military service in Iraq or Afghanistan. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 2016. May;42(3):269–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clarke-Walper K, Riviere LA, Wilk JE. Alcohol misuse, alcohol-related risky behaviors, and childhood adversity among soldiers who returned from Iraq or Afghanistan. Addict Behav 2014;39:414–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Damron-Rodriguez J, White-Kazemipour W, Washington D, Villa VM, Dhanani S, Harada ND. Accessibility and acceptability of the Department of Veteran Affairs health care: diverse veterans’ perspectives. Mil Med 2004;169:243–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dawson DA. Methodological issues in measuring alcohol use. Alcohol research & health : the journal of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism 2003;27:18–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dawson DA, Grant BF, Li TK. Quantifying the risks associated with exceeding recommended drinking limits. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research 2005;29:902–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Derefinko KJ, Hallsell TA, Isaacs MB, et al. Substance Use and Psychological Distress Before and After the Military to Civilian Transition. Mil Med 2018;183:e258–e265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fuehrlein BS, Kachadourian LK, DeVylder EK, et al. Trajectories of alcohol consumption in U.S. military veterans: Results from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study. Am J Addict 2018. doi: 10.1111/ajad.12731 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goldmann E, Calabrese JR, Prescott MR, et al. Potentially modifiable pre-, peri-, and postdeployment characteristics associated with deployment-related posttraumatic stress disorder among ohio army national guard soldiers. Annals of epidemiology 2012;22:71–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gordon S. Wounds of War: How the VA Delivers Health, Healing, and Hope to the Nation’s Veterans. In: Ithaca, NY, United States: Cornell University Press, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gorman LA, Blow AJ, Ames BD, Reed PL. National Guard families after combat: mental health, use of mental health services, and perceived treatment barriers. Psychiatric services (Washington, DC) 2011;62:28–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harrell FE Jr., Lee KL, Mark DB. Multivariable prognostic models: issues in developing models, evaluating assumptions and adequacy, and measuring and reducing errors. Statistics in medicine 1996;15:361–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holmes TH, Rahe RH. The Social Readjustment Rating Scale. Journal of psychosomatic research 1967;11:213–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jacobson IG, Ryan MA, Hooper TI, et al. Alcohol use and alcohol-related problems before and after military combat deployment. JAMA 2008;300:663–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jewell NP. Test of consistency of association across strata, in: Statistics for Epidemiology. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, pp. 158–159. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keyes KM, Hatzenbuehler ML, Hasin DS. Stressful life experiences, alcohol consumption, and alcohol use disorders: the epidemiologic evidence for four main types of stressors. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011;218:1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim PY, Toblin RL, Riviere LA, Kok BC, Grossman SH, Wilk JE. Provider and Nonprovider Sources of Mental Health Help in the Military and the Effects of Stigma, Negative Attitudes, and Organizational Barriers to Care. Psychiatric services (Washington, DC) 2016;67:221–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kroenke K, Strine TW, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Berry JT, Mokdad AH. The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. J Affect Disord 2009;114:163–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Littman AJ, Boyko EJ, Jacobson IG, et al. Assessing nonresponse bias at follow-up in a large prospective cohort of relatively young and mobile military service members. BMC Med Res Methodol 2010;10:99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Littman AJ, Jacobson IG, Boyko EJ, Powell TM, Smith TC, Millennium Cohort Study T. Weight change following US military service. International journal of obesity 2013;37:244–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mattiko MJ, Olmsted KL, Brown JM, Bray RM. Alcohol use and negative consequences among active duty military personnel. Addict Behav 2011;36:608–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Milliken CS, Auchterlonie JL, Hoge CW. Longitudinal Assessment of Mental Health Problems Among Active and Reserve Component Soldiers Returning From the Iraq War. JAMA 2007;298:2141–2148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moyer A, Finney JW. Meeting the challenges for research and practice for brief alcohol intervention. Addiction (Abingdon, England) 2010;105:963–4; discussion 964–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Naimi TS, Brewer RD, Mokdad A, Denny C, Serdula MK, Marks JS. Binge drinking among US adults. JAMA 2003;289:70–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Orr MG, Prescott MR, Cohen GH, et al. Potentially modifiable deployment characteristics and new-onset alcohol abuse or dependence in the US National Guard. Drug Alcohol Depend 2014;142:325–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ouellette JA, Wood W. Habit and Intention in Everyday Life: The Multiple Processes by Which Past Behavior Predicts Future Behavior Psychological bulletin 1998;124:54–74. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Porter B, Hoge CW, Tobin LE, et al. Measuring Aggregated and Specific Combat Exposures: Associations Between Combat Exposure Measures and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, Depression, and Alcohol-Related Problems. J Trauma Stress 2018;31:296–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ryan MA, Smith TC, Smith B, et al. Millennium Cohort: enrollment begins a 21-year contribution to understanding the impact of military service. J Clin Epidemiol 2007;60:181–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saha TD, Stinson FS, Grant BF. The role of alcohol consumption in future classifications of alcohol use disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend 2007;89:82–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saitz R. Clinical practice. Unhealthy alcohol use. The New England journal of medicine 2005;352:596–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shield KD, Parry C, Rehm J. Chronic diseases and conditions related to alcohol use. Alcohol research : current reviews 2013;35:155–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. JAMA 1999;282:1737–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Whitlock EP, Polen MR, Green CA, Orleans T, Klein J. Behavioral counseling interventions in primary care to reduce risky/harmful alcohol use by adults: a summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Annals of internal medicine 2004;140:557–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Williams EC, Frasco MA, Jacobson IG, et al. Risk factors for relapse to problem drinking among current and former US military personnel: a prospective study of the Millennium Cohort. Drug Alcohol Depend 2015;148:93–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Williams EC, Johnson ML, Lapham GT, et al. Strategies to implement alcohol screening and brief intervention in primary care settings: a structured literature review. Psychol Addict Behav 2011;25:206–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Williams EC, McGinnis KA, Bobb JF, et al. Changes in alcohol use associated with changes in HIV disease severity over time: A national longitudinal study in the Veterans Aging Cohort. Drug Alcohol Depend 2018;189:21–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Woodall KA, Jacobson IG, Crum-Cianflone NF. Deployment experiences and motor vehicle crashes among U.S. service members. Am J Prev Med 2014;46:350–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]