Abstract

Objectives:

To evaluate the secondary impact of a multilevel, child-focused, obesity intervention on food-related behaviors (acquisition, preparation, and fruit and vegetable (FV) consumption) on youths’ primary caregivers.

Design:

B’more Healthy Communities for Kids (BHCK), group-randomized, controlled trial, promoted access to healthy food and food-related behaviors through wholesaler and small store strategies, peer-mentor led nutrition education aimed at youth, and social media and text messaging targeting their adult caregivers. Measures included caregivers’ (n=516) self-reported household food acquisition frequency for FV, snacks, and grocery items over 30 days, and usual consumption of FV in a sub-sample of 226 caregivers via the NCI FV Screener. Hierarchical models assessed average-treatment-effects (ATE). Treatment-on-the-treated-effect (TTE) analyses evaluated the correlation between behavioral change and exposure to BHCK. Exposure scores at post-assessment were based on self-reported viewing of BHCK materials and participating in activities.

Setting:

30 Baltimore City low-income neighborhoods

Subjects:

Adult caregivers of youth ages 9–15 years.

Results:

90.89% of caregivers were female, average 39.31(± 9.31) years. Baseline mean fruit intake (servings/day) was 1.30(± 1.69) and vegetable was 1.35(± 1.05). In ATE, no significant effect of the intervention was found on caregiver food-related behaviors. In TTE, for each point increase in the BHCK exposure score (range 0–6.9), caregivers increased daily consumption of fruits by 0.2 servings (0.24± 0.11; 95%CI 0.04; 0.47). Caregivers reporting greater exposure to social media tripled their daily fruit intake (3.16± 0.92; 95%CI 1.33; 4.99) and increased frequency of unhealthy food purchasing, compared to baseline.

Conclusions:

Child-focused community-based nutrition interventions may also benefit family members’ fruit intake. Child-focused interventions should involve adult caregivers and intervention effects on family members should be assessed. Future multilevel studies should consider using social media to improve reach and engage caregiver participants.

Keywords: Fruit and vegetable, adult health, environmental intervention, African American, food purchasing, childhood obesity

Introduction

Dietary consumption leading to an energy imbalance is among the most proximal drivers of obesity.(1) Diets today, especially in low-income, urban communities of color, are often characterized by high intake of refined carbohydrates, added sugars, fats, and salt due to high consumption of energy dense, processed foods.(2; 3) Analyses of nationally representative surveys have demonstrated increased intake of high energy-dense foods, such as sugar-sweetened beverages(4) and snacks(5), in the past three decades among U.S. adults. Despite recent findings showing improvement in dietary quality from 1999–2012 among the overall adult population(6), African Americans and Hispanic adults continue to have the lowest dietary quality in the country.(7) These disparities in diet quality are likely influenced by racial and ethnic residential segregations and inequalities in availability, access, and affordability of nutrient-dense foods and resources.(8; 9; 10; 11)

In view of the multifactorial etiology of weight gain, efforts that simultaneously address multiple levels of the food system are recommended.(12) One example of such efforts are multilevel multicomponent community-based interventions, in which different levels of influence are targeted to change the food environment surrounding the individual, and to promote behavioral change.(13) Despite recognizing the importance of the various levels of influence outlined in socio ecological models (i.e., individual, household, organizational, community, policy)(14), most multilevel childhood obesity prevention interventions have primarily delivered nutrition education in school settings, yielding mixed results(15; 16), with limited activities to modify the out of school environment and for engaging families.(17) Furthermore, insufficient evaluation of the impact of multilevel community-based childhood obesity prevention trials on diet and food behaviors in children and their caregivers exists.(18)

Childhood obesity prevention interventions that also engaged adult caregivers have shown more positive child-related outcomes than child-only interventions.(19; 20) However, few child-focused interventions have reported impacts on caregiver behavioral outcomes(21), due to limited assessment of nutrition behaviors among this group.(22) Understanding the impact of childhood obesity prevention on caregivers is important because families’ eating practices, rules, and support influence children to initiate and sustain positive dietary changes, while providing opportunities for social learning.(23) Therefore, we evaluated the secondary impact of a child-focused community intervention on youths’ adult caregivers food acquisition, preparation, and fruit and vegetables (FV) consumption.

B’more Healthy Communities for Kids (BHCK) was a community-based multilevel multicomponent childhood obesity prevention intervention that sought to modify the food environment outside of school for low-income 9–15 years old youth in Baltimore, U.S.(24) We hypothesized that caregivers would have improved food-related behaviors in part due to the environmental changes of the BHCK intervention and educational activities through social media and texting. For instance, BHCK improved availability and promotion of healthful foods and beverages in small food stores (i.e., corner stores/carryout restaurants) that were frequented by youth outside of school hours and located in the neighborhoods where BHCK families lived.(25) Caregivers may also have been exposed to or attended community nutrition education sessions given that intervention activities in intervention neighborhoods were public and available to all community members.(26) In addition, caregivers could have also been exposed to flyers, giveaways that were brought home by youth attending BHCK activities in the after-school nutrition education sessions for youth. Lastly, BHCK social media and text-message intervention components targeted adult caregivers, in which its content aimed to reinforce health-related messages utilized at other BHCK intervention components.

Multilevel multicomponent interventions are implemented as synergistic interventions with components reinforcing one another at different levels(27); however, this limits the researcher’s ability to identify which specific component was more successful in influencing behavior change. Another consideration for multilevel multicomponent community-based interventions is regarding the extent to which intervention components are implemented with sufficient intensity.(28) One approach to identifying the intervention component that led to behavior change in multilevel multicomponent interventions, is to conduct treatment-on-the-treated effect (TTE) as a secondary impact analysis, in which study participants are analyzed according to the treatment received, instead of the original treatment assigned (average treatment effects - ATE).(26) Although causality cannot be inferred, this analysis may provide information about the dose response relationship between level of exposure to the intervention and behavioral change, and may identify specific intervention components that are more likely to influence the outcomes.(29)

Therefore, this manuscript aimed to answer the following questions:

What was the impact of the multilevel BHCK intervention on food-related behaviors (purchasing of healthier and unhealthier food items, food preparation and consumption of fruits and vegetables) among adult caregivers?

Was change in food-related behaviors associated with caregiver’s exposure level (‘dose received’) to the BHCK intervention?

What component of the multilevel BHCK intervention was correlated with changes in food-related behaviors among caregivers?

Methods

Study design

BHCK employed a group randomized controlled trial design with two intervention arms (random allocation to treatment on a 1:1 basis), implemented in two rounds (waves). A detailed description of the formative research, trial design, and sample size calculation has been published elsewhere.(24)

The intervention integrated different levels of an ecological model and multiple intervention components into a food systems approach from wholesalers, to small food stores, and to families that promoted access to nutritious food and balanced diets. Using a socio ecological model for health promotion, the BHCK intervention tapped into the dynamic interplay among individual, behavioral, household, environmental, and policy levels.(14) Individual-level components were based in community recreation centers, using youth-leaders (college and high-school trained mentors) to provide education and nutrition skills to youth (9–15 years old). The family-level included social media and texting. Social media (Facebook and Instagram) were used to integrate the different levels of BHCK to inform family-level nutrition behaviors. Recipes, news, and BHCK-specific activities were featured in these communication channels. Text messages (sent 3 times/week) and social media platforms also targeted mainly youth’s caregivers by guiding them to set and achieve goals to healthier behaviors for themselves and their families, as well as promoting BHCK community activities. An example of a goal setting text message was as follows: “Does your child have a sweet tooth? Try offering them granola bars or fruit as an alternative to candy 1 time this week.” Intervention flyers and promotion of the intervention were mailed to caregivers and youth twice a month at the end of Wave 2 only. An overview of the intervention is presented in Table 1.

Table 1:

Description of the B’more Healthy Communities for Kids intervention as implemented

| BHCK Intervention Components | Goal | Materials | Delivery | Duration | Implementationa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wholesaler(40) (n=3) | Ensure stocking of BHCK-promoted food items | - In-store signage (shelf-labels) of promoted items - Provision of $50 gift cards from wholesalers to BHCK intervention stores - Wholesaler circulars with BHCK logo highlighting promoted foods |

1x/month in-person visit by a BHCK-interventionist to maintain shelf-labels position, and monitor availability of promoted items |

Wave 1: July 2014 to Feb 2015 Wave 2: Dec 2015 to July 2016 Total # visits/wholesaler/wave: 6 Length of visits to wholesalers: 1–4hs |

Reach: high Dose delivered: high Fidelity: high |

| Small corner stores(40) and carryout restaurants(41) (n=50) | Improve supply and demand for healthier options of foods/beverages in low-income areas | - Gift cards from wholesalers for initial stocking - Stocking sheet with promoted items/ intervention phase -Online training modules for store owners - Store supplies as a reward for watching training modules (ranging from produce baskets to refrigerators) - Point-of-purchasing promotions and giveaways to customers - Poster and handouts promoting BHCK items -In-store taste tests |

BHCK-interventionists conducted in-store taste testing, put up communication materials, maintained shelf-label position, and monitored availability of promoted items |

Wave 1: July 2014 to Feb 2015 Total # sessions/store: 12 Wave 2: Dec 2015 to July 2016 Total # sessions/store: 15 In-store educational sessions were implemented every other week in each intervention store Length of in-store promotion sessions: 2h |

Reach: medium Dose delivered: medium Fidelity: medium-high |

| Youth-led (n=18) nutrition education in recreation centers(42) (n=14) | Hands-on nutrition education activities delivered by youth-leaders (college and high school Baltimore students) to children in the 9–15-year range attending the after-school program at the time of the intervention. | - BHCK youth-leaders were trained by BHCK-interventionist (35h) - Nutrition sessions followed the themes of each BHCK phase: 1) healthful beverages, 2) healthful snacks, and 3) healthful cooking methods - Giveaways and taste-tests with children at the end of each session - Posters put up in centers - Handouts distributed to children |

Trained youth-leaders were involved in the delivery of the intervention based on the perspectives of social cognitive theory, to encourage mentees to model mentors’ health behavior. Average of 2 youth-leaders/session/center 2 BHCK-interventionists oversaw execution of sessions to monitor quality of implementation of the intervention |

Wave 1: July 2014 to Feb 2015 Total # sessions/center: 14 Wave 2: Dec 2015 to July 2016 Total # sessions/center: 14 Nutrition sessions were implemented every other week by youth leaders Session length: 1h |

Reach: medium Dose delivered: medium Fidelity: high |

| Social media and texting(43) | Integrate all components of intervention and promoted nutrition knowledge, goal setting, and BHCK activities to adult caregivers | - Two social media platforms (Facebook & Instagram) featured recipes, news, and BHCK-specific activities related to promoted items and behaviors - Adult caregivers enrolled in the BHCK study (intervention group only) received a text message related to healthier eating behavior - Intervention households received weekly mailings with intervention flyers and promotional materials |

Social medias posts were delivered daily BHCK-interventionists monitored posts daily Bi-directional text messages were sent 3–5 times a week BHCK-interventionists sent weekly mailings, alternating child- and caregiver-targeted contents. |

Social Media: Wave 1 and 2: June 2014 to Jan 2017 Text message: Wave 1: July 2014 to Feb 2015 Wave 2: Dec 2015 to July 2016 Mailing: Wave 2 only: April to July 2016 9 mailings to caregivers and 7 directed at youth |

Reach: high Dose delivered: high Fidelity: high |

| Policy(44) | Work with city stakeholders to support policies for a healthier food environment in Baltimore, and to sustain BHCK activities | - Evidence-based information to support the development of policies at the city level using agent-based models to simulate impact to aid stakeholder decision-making (e.g. urban farm tax credit) | BHCK policy working group formed by BHCK-interventionists and research group, city councilmen, food policy director, wholesaler manager, Recreation and Parks Department, Health Department. | July 2013 to July 2016 10 meetings (2h) with stakeholders (every 4 months) |

Reach: high Dose delivered: medium Fidelity: medium |

Abbreviation: BHCK, B’more Healthy Communities for Kids

Implementation (process evaluation) definitions:

Reach: number of people in the target audience participating in each intervention activity.

Dose delivered: units of intervention materials/activities (e.g. nutrition sessions, posters, flyers) provided by BHCK interventionists

Fidelity: quality of intervention component implementation, based on reactions to or engagement with the program

High (≥100%), medium (50–99.9%) or low (<50%) is in reference to a priori set standard.

The BHCK intervention promoted healthful foods/beverages and behaviors in three sequential phases, each lasting two months: 1) healthier beverages (i.e., lower-sugar fruit drinks (25–75% less sugar than the original version), sugar-free drink mixes, zero-calorie flavored water, diet or low-sugar soda, and water), 2) healthier snacks (i.e., low-fat yogurt, low-fat popcorn, fresh fruits, fresh vegetables, low-sugar granola bars, and mixed fruits in 100% fruit juice), and 3) healthier cooking methods (i.e., cooking ingredients, such as low-sugar cereals, low-fat milk, 100% whole wheat bread, fresh/canned/frozen vegetables). A fourth phase, intended to review main messages covered in the previous phases, was implemented in Wave 2 only.

Setting

The trial took place in 30 low-income, predominantly African-American neighborhood zones in Baltimore, with low access to healthy food. Zones were defined as a 1.5-mile area around a recreation center (nucleus). Eligibility criteria for BHCK zones were: 1) predominantly African-American (>50%); 2) low-income (>20% of residents living below the poverty line); 3) ≥ 5 small (<3 aisles, no seating) food sources (e.g., corner stores and carryout restaurants); 4) having a recreation center more than ½ mile away from a supermarket.(30) The 30 zones were randomized into intervention (n=14) and comparison (n=16) groups, with recreation centers as the main unit of randomization. Wave 1 was implemented from July 2014-February 2015 (n=7 intervention and 7 comparison zones), and Wave 2 from December 2015-July 2016 (n=7 intervention and 9 comparison zones).

Subjects

After randomly selecting BHCK zones, a sample of adult caregivers and their children were recruited in the recreation centers and around the stores within the 1.5-mile buffer zone. Eligibility for the adult caregiver and child participants were determined at the household level. Household eligibility criteria were as follows: (1) being a caregiver (>18 years old) of at least one child aged 9–15 years; (2) living in the same location for at least one month; and (3) not anticipating a move in the next two years. Child and caregivers received $30 and $20 gift cards, respectively, after each of the pre- and post-intervention interviews.

Training of interventionists and data collectors

BHCK-interventionists were graduate students, public health educators, dietitians, or youth-leaders trained in nutrition and health education, and were not masked to the group (zone) assignment. Data collectors were graduate students and staff who were intensively trained, including through role plays and observations. They were masked after assignment to intervention to reduce information bias.

Measures

Caregiver data collection

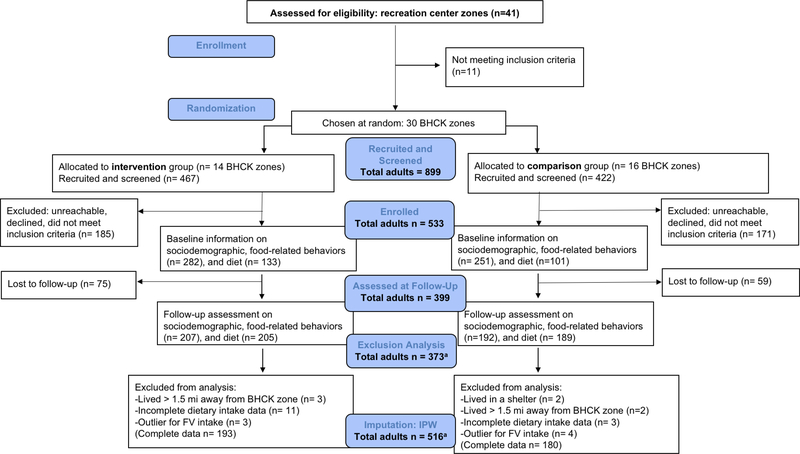

Baseline data were collected from June 2013 to June 2014 (Wave 1) in a total of 298 adult caregivers, and from April to November 2015 (Wave 2) in 235 caregivers. A post-evaluation was conducted from March 2015 to March 2016 (Wave 1) and from August 2016 to January 2017 (Wave 2), taking place immediately after implementation of the intervention to one year (Wave 1) or up to six months (Wave 2). We did not analyze participants who reported living in unstable housing arrangements such as in shelters or transitional housing (n=2), lived more than 1.5 miles away from a BHCK recreation center (n=5), had incomplete dietary intake data (n=14), or were considered an outlier (>10 servings/day, or >99.5th percentile) for fruit and vegetable intake (n=7), yielding a total of 373 participants with complete baseline and follow-up information for the analytical sample (Figure 1).

Figure 1: CONSORT flowchart of the randomization and course of the B’more Healthy Communities for Kids intervention.

a Analyses accounted for missing data and selection bias using inverse probability weighted (IPW) method, with the probability of being observed at follow-up as a function of the characteristics of caregiver (age, sex, and income) and study wave; final imputed sample size in the multilevel analysis n = 516.

Fruit and vegetable consumption

The National Cancer Institute (NCI) FV screener was used to collect usual consumption of 10 categories of FV intake in adult caregivers over the past month. It is a short dietary assessment instrument consisting of 14 questions and is a modified version of the FV screener from the Eating at America’s Table Study.(31) The screener inquired about frequency of intake of fruit, 100% fruit juice, and vegetables (lettuce, greens, potatoes, and legumes) consumed in a monthly, weekly, or daily basis. The amount of each food item was estimated as cups or servings and self-reported by the participant. We calculated the total number of both fruit and vegetable servings consumed daily using the 2005 MyPyramid definition of cup equivalents. For each food group, we multiplied the average frequency (daily) by the cup equivalent. The instrument has been validated and presents high correlations with 24-hour dietary recall, and is less burdensome compared to other instruments.(32) Food models were used to improve accuracy of serving size information. The NCI FV Screener was added to the data collection protocol after the Wave 1 intervention had begun and was first administered during Wave 1 post-intervention. Therefore, the effect of the intervention on FV intake of adults was calculated only using BHCK Wave 2 sample with pre- and post-evaluation data (n=196), as this instrument was not used during Wave 1 baseline data collection.

Household food preparation

Adult caregivers reported their frequency of meal preparation (cooking methods) for the household in the previous 30 days from the interview.(33) In addition, respondents ranked the top three most common cooking methods used when they prepared chicken, turkey (including ground turkey and turkey bacon), pork (including bacon), ground beef, fish, eggs, greens (excluding lettuce), and potatoes. The survey was adapted from an instrument used in a similar study(33), and on the basis of formative research.(34)

We created a healthful cooking score using similar methods previously reported in the literature.(35) Cooking methods were assigned values based on the amount of fat used, as follows: deep fry or pan-fried with oil (−2); pan-fried, drained or use of cooking spray (−1); not prepared in the last 30 days (0); pan-fried, drained, and rinsed with hot water (+1); broiled/baked, or grilled, or steamed, or boiled, or raw, or microwaved (+2). The scores were separately calculated for each food, weighted according to the most commonly reported method to estimate the healthiness of the cooking preparation: 60% (first method most commonly used), 30% (second method), and 10% (third method). For example, if chicken was most commonly pan-fried, second most commonly grilled, and third most commonly cooked with cooking spray, the score was calculated as (0.60 × −2) + (0.30 × 2) + (0.1 × −1) as an indicator of the overall healthiness of chicken preparation. Then, the scores for all of 8 foods were summed to obtain the overall household food preparation score (mean: −0.07 (0.88), range −1 to 2.1).

Frequency of food acquisition

Caregivers reported the number of times they acquired food from different food sources in the previous 30 days from the interview date (e.g., “How many times did you get these foods?”). Food acquisition included all of the following: food/beverages that were purchased with cash purchased with food safety net program benefits (SNAP, WIC), and food that was obtained for free (i.e., from pantries or donated by family/friends).(36)

A list of 33 BHCK-promoted healthier foods and beverages and 21 less healthful foods and beverages was provided, and respondents reported the number of times they had acquired each food in the specified timeframe. Prepared foods acquired from delis, vendors, or restaurants were not included, as this instrument was designed to measure foods purchased for consumption in the home environment rather than for immediate consumptions. The list was designed on the basis of formative research conducted with the community(33), and reflected foods promoted during the BHCK intervention. Face and content validity of the questionnaire were assessed on 15 randomly selected adult caregivers during the pilot phase.(33) The healthful and less healthful food acquisition variables were additive items based on the acquisition frequency of 33 healthful and 21 less healthful foods for each respondent and divided by 30 to yield a daily frequency score, respectively. Additive daily healthful food acquisition frequency ranged from 0.6 to 4.8 with a mean of 0.9 (SD = 0.6), and less healthful food acquisition frequency from 0.1 to 10.2 with a mean of 1.3 (SD = 1.1).

Exposure score

The key variables for assessing exposure (‘dose received’) were obtained using the 29-item Intervention Exposure Questionnaire (IEQ) collected as part of the post-intervention assessment for intervention and comparison groups. The IEQ measured participant’s self-reported viewing of BHCK communication materials (posters, handouts, giveaway), participation in food environment intervention activities (i.e., taste tests, seeing educational displays, redesigned carryout restaurants’ menu, and store promotional shelf-labels), and enrollment in social media/viewing of media posts, and receiving the text messaging program.(26) In addition, eight red herring questions were used to address response bias, and included materials used in previous studies conducted at other sites. We classified individuals into tertiles of red herring responses, where selecting 0–2 red herring answers was considered truthful, 3–5 moderate, 6–8 untruthful responses and kept only individuals in the tertile with the least number of red herring responses. No respondent answered positively to >3 (1/3 or more) of the red-herring questions; thus, none of the caregivers with complete responses were excluded from the analysis.

We calculated exposure scores for each component of the BHCK intervention to which adults could be exposed (communication materials, food environment intervention, social media, and texting) and an overall BHCK exposure score. Detailed description of the formation of the exposure score is presented in Table 2 and published elsewhere.(26) For each intervention component, points were assigned for exposure to study materials/activities and then scaled into proportions (0–1 range), yielding an overall BHCK exposure score of 11 points (possible highest score). A total of 370 adult caregivers had complete exposure data information.

Table 2:

Formation of Exposure Scores by B’more Healthy Communities for Kids intervention materials and activities

| Intervention Component | Intervention Material or Activity | Coding of Exposure Score | Observed mean scores (SE) | p-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Comparison | ||||

| Communication Materials | Seeing BHCK Logo in different places (stores, recreation centers, carryout restaurants, social media)b | None = 0 1–2 places = 1.5 3–5 places = 4 6 or more = 6 |

0.86 (0.05) Range: 0– 3.2 |

0.27 (0.03) Range: 0 – 2. |

<0.001 |

| Posters (10 questions) | For each poster: Yes = 1 Maybe = 0.5 No = 0 |

||||

| Handouts (9 questions) | For each handout: Yes = 1 Maybe = 0.5 No = 0 |

||||

| Giveaways (17 questions) | For each giveaway: Yes = 1 Maybe = 0.5 No = 0 |

||||

| Food Environment | Seeing shelf-label in different stores (BHCK corner stores and carryouts)b | None = 0 1–2 places = 1.5 3–5 places = 4 6 or more = 6 |

0.42 (0.03) Range: 0– 2.9 |

0.23 (0.04) Range 0 – 2 |

<0.001 |

| Taste tests (10 questions) (and 4 cooking demos at recreation center – applied to child only) | For each taste test: Yes = 1 Maybe = 0.5 No = 0 |

||||

| Educational Display (5 questions) | For each display: Yes = 1 Maybe = 0.5 No = 0 |

||||

| Seeing redesigned menu (8 questions) | For each menu: Yes = 1 Maybe = 0.5 No = 0 |

||||

| Purchased in a BHCK corner store in the past 7 days | Continuous variable: total frequency of purchase summed for all stores (n=21) | ||||

| Social Media | Follow or enrolled in BHCK social media (Facebook, Instagram) | For each account: Yes =1 No = 0 |

0.08 (0.01) Range: 0 – 1 |

0.04 (0.01) Range 0 – 2 |

0.06 |

| Seeing BHCK posts (Facebook or Instagram) (8 questions) | For each post: Yes = 1 No = 0 |

||||

| Text-Message | Weekly frequency of receiving a BHCK text message | None = 0 1/week = 1 2/week = 2 3 or more/week = 3 |

0.55 (0.02) Range 0 – 1 |

0.26 (0.02) Range 0 – 1 |

<0.001 |

| Overall BHCK Exposure Score | 1. Added points within each intervention material/activity according to number of questions 2. Re-scaled exposure to material/activity to 0–1 range 3. Summed all re-scaled exposure scores by intervention components |

1.92 (0.08) Range 0– 6.4 |

0.82 (0.07) Range 0– 6.7 |

<0.001 | |

Abbreviations: SE, standard error; BHCK, B’more Healthy Communities for Kids

p-value based on two-tailed t-test comparing mean scores between intervention and comparison groups.

we asked participants the number of places where they saw the BHCK logo or saw a BHCK shelf-label at a corner store with four possible answers (None; 1–2 places; 3–5 places; 6 or more). When coding, we chose the average number in the range of places they reported seeing the intervention materials (i.e., 0, 1.5, 4, 6, respectively). Then, we re-scaled the points to range from 0 to1 to make all the intervention materials exposure score equivalent before summing by exposure components (communication materials, food environment, social media, and text messages).

Covariates

Caregivers were assessed on: demographics and household socioeconomic information (age, sex, caregiver education level (categorized into < high school, completed high school, and > high school), employment status, and household income (US$0–10,000; 10,001–20,000; 20,001–30,000 or higher), housing arrangement (owned, rent, and shared with family or other arrangement (group housing, transitional housing)), and household participation in food assistance programs. These programs included receiving the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) or Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits in the past year. Caregivers also had their anthropometric measures taken (height using a stadiometer and weight using a portable scale) after removing shoes and heavy clothing. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height squared (m2).

Data analysis

All analyses were conducted using Stata 13.1 (College Station, TX). Descriptive statistics were performed to characterize the study sample at baseline by study group assignment. Continuous variables were tested for differences between intervention and comparison groups with independent two-tailed t-tests. The Chi-square test for proportions was used for categorical variables. Variable and model residual distributions were examined for normality and extreme values (outliers) using quantile-quantile plots and goodness of fit tests (Kolmogorov-Smirnov).

The average treatment effects (ATE) on the change in diet, food preparation, and food-acquisition behaviors among adult caregivers were assessed by the difference between the mean change of the outcome in the intervention group compared to the control group. We tested the intervention effect on adult caregivers’ food-related behaviors using a multilevel linear mixed-effect model fit by maximum likelihood. Random effects accounted for variation at the BHCK zone and at the caregiver-level (repeated measures).

Due to the 24.9% attrition rate, we used inverse probability weighting (IPW) to address potential bias due to loss to follow-up and to correct for the effects of missing data.(37) Using all available data, we estimated weights for every missing outcome of interest fitting a logistic regression model. We treated the categorical indicator of response at follow-up as the outcome variable, regressed on the baseline response for intake, preparation, or acquisition, with age, sex, income, wave (predictive of dropout) as covariates. Once the weights were determined, they were incorporated in the multilevel linear mixed-effect analysis using the pweight option for the mixed command in Stata. Results of the ATE analysis using only completed-cases without the IPW method are shown in Supplemental Table 1.

We also conducted a treatment-on-the-treated effect (TTE) analysis, in which study participants were analyzed according to the treatment received,(29) as estimated by their exposure scores. We conducted multiple linear regression models to analyze the association between the change in caregivers’ food behaviors (intake, preparation, and acquisition) and caregiver exposure levels (total exposure score, and by exposure to intervention components), adjusted for age, sex, income, and household size. We used a bootstrap method with 2000 repetitions and bias-corrected confidence intervals to account for the within-individual correlation of the data, clustered on the BHCK zone.(38; 39) For the significant results, we estimated the proportion of variability explained (effect size) with omega-squared (ω2) after fitting the multivariate models. A sensitivity analysis using multiple logistic regression on the correlation between the categorical change in food-related behavior (no change versus positive change) and the exposure scores (low (if 0) versus high (if above 0)) was also conducted to estimate the standardized effect size given by the odds ratio. Given the time frame for follow-up data collection differed by wave, we conducted tests of homogeneity to explore if the effect of exposure was moderated by the two BHCK Waves.

For all analyses, we reported the 95% confidence intervals (CI). Statistical significance was defined by a p-value of < 0.05.

Results

Implementation of each component of the BHCK intervention was evaluated through detailed process evaluation reported elsewhere.(40; 41; 42; 43; 44) Table 1 illustrates implementation quality of each BHCK component. The intervention was implemented with overall moderate- to high-reach, dose delivered, and fidelity.(45)

On average, caregivers presented an overall BHCK exposure score of 1.38 points, SD ± 1.2 (range: 0–6.9), BHCK Communication Materials exposure score (mean: 0.6 (observed range: 0.0 – 3.1), possible highest score: 4), Food Environment exposure score (mean: 0.3 (observed range: 0.0–3.1), possible highest score: 5), Social Media exposure score (mean: 0.2 (observed range: 0.0–2), possible highest score: 2); and a Text Messaging exposure score based on the frequency of BHCK text messages received per week (mean: 1.10 (observed range: 0–3).

When comparing the overall exposure scores between the groups, caregivers in the intervention group demonstrated significantly higher mean exposure scores than adult caregivers in the comparison group (intervention: mean 1.90 ± 0.08; comparison: mean 0.82 ± 0.07, p<0.001) (Table 2). Even though the comparison group was exposed to the BHCK intervention components, the intervention group had significantly higher exposure scores than the comparison group for the communication materials, food environment, and text message components (p<0.001). Social media exposure scores were not statistically significantly different when comparing group means (p=0.06). Reported exposure level to the BHCK intervention was low among caregivers.

Characteristics of the baseline BHCK evaluation sample

The vast majority of our study sample self-identified as African-American (96.6%), and 49% of caregivers were either overweight or obese (Table 3). Most caregivers were female (93.2%) and from a household that received SNAP (70.8%). Significant differences were found between treatment groups with respect to caregiver’s age (p=0.01), being higher in the comparison group.

Table 3:

Baseline characteristics of the B’more Healthy Communities for Kids adult caregiver sample

| Baseline characteristics | n (516) | Intervention | Comparison | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n= 280) | (n= 247) | |||

| Caregiver | ||||

| Gender – female (%) | 469 | 53.30 | 46.70 | 0.39 |

| Age (years) – mean (SD) | 515 | 38.20 (8.63) | 40.60 (9.87) | 0.01* |

| African American (%) | 478 | 48.84 | 43.80 | 0.99 |

| Education level | ||||

| < High school (%) | 90 | 58.89 | 41.11 | 0.43 |

| High school (%) | 207 | 52.17 | 47.83 | |

| > High school (%) | 218 | 50.92 | 49.08 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) – mean (SD) | 512 | 34.18 (8.05) | 33.04 (7.31) | 0.09 |

| Normal weight (%) | 65 | 55.38 | 44.62 | 0.82 |

| Overweight (%) | 99 | 50.51 | 49.49 | |

| Obesity (%) | 344 | 52.62 | 47.38 | |

| Household | ||||

| Individuals in the household - mean (SD) | 516 | 4.63 (1.66) | 4.53 (1.62) | 0.49 |

| Annual income (US$) | ||||

| 0–10,000 (%) | 120 | 13.76 | 9.50 | 0.13 |

| 10,001–20,000 (%) | 117 | 10.08 | 12.60 | |

| 20,001–30,000 (%) | 93 | 10.08 | 7.95 | |

| >30,000 (%) | 186 | 18.80 | 17.25 | |

| Food security a | ||||

| Food secure (%) | 302 | 55.88 | 61.48 | 0.19 |

| Food insecure (%) | 214 | 44.12 | 38.52 | |

| Food assistance participation | ||||

| SNAP (%) | 516 | 75.00 | 70.49 | 0.25 |

| WIC (%) | 516 | 21.69 | 22.13 | 0.90 |

| Housing arrangement | ||||

| Living w/ family or other (%) | 53 | 8.46 | 12.30 | 0.34 |

| Rented (%) | 353 | 70.22 | 66.39 | |

| Owned (%) | 110 | 21.32 | 21.31 | |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation; BMI, Body Mass Index; SNAP, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program; WIC, The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children

Food security classified according to USDA ERS measure. Food secure households encompassed high food security and marginal food security. Food insecure households were either low food secure or very low food secure.

Intervention groups are statistically different (p<0.05) when comparing the proportion of adult characteristics using the chi-square test or means with two-tailed t-test.

Impact of BHCK intervention on food-related behavior of caregivers

In the ATE analysis, we did not find a significant effect of the intervention on the food acquisition, home food preparation, and daily consumption of FV among intervention adult caregivers compared to their counterparts (Table 4).

Table 4:

Impact of the B’more Healthy Communities for Kids intervention on food-related behaviors among adult caregivers: Average-Treatment-Effects analysis

| Caregiver food-related behaviorsa,b | Predicted Baseline |

Predicted Post-intervention |

Pre-post change: difference c |

p | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention |

Comparison |

Intervention |

Comparison |

|||||||

| Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Effect (95% CI) | ||

| Acquisition (frequency/day) d | ||||||||||

| Healthful food score | 1.48 | 0.07 | 1.49 | 0.06 | 1.37 | 0.07 | 1.43 | 0.06 | −0.05 (−0.22; 0.12) | 0.57 |

| Unhealthful food score | 1.29 | 0.06 | 1.40 | 0.07 | 1.21 | 0.06 | 1.34 | 0.10 | −0.01 (−0.23; 0.19) | 0.87 |

| Home meal preparation | ||||||||||

| Frequency of meal preparation (monthly) | 33.82 | 2.24 | 36.79 | 1.87 | 32.69 | 1.34 | 38.82 | 2.36 | −3.12 (−9.11; 2.81) | 0.30 |

| Healthful cooking score | −0.01 | 0.04 | −0.01 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.07 | −0.06 | 0.07 | −0.01 (−0.24; 0.20) | 0.88 |

| Daily Consumption (srv/day) e | ||||||||||

| Total fruit | 1.10 | 0.07 | 1.46 | 0.25 | 0.96 | 0.14 | 1.17 | 0.16 | 0.15 (−0.36; 0.66) | 0.55 |

| Total vegetable | 1.23 | 0.04 | 1.44 | 0.11 | 0.94 | 0.02 | 1.29 | 0.17 | −0.13 (−0.54; 0.25) | 0.51 |

| Total fruit and vegetable | 2.33 | 0.08 | 2.92 | 0.29 | 1.90 | 0.14 | 2.44 | 0.23 | 0.07 (−0.42; 0.53) | 0.78 |

Abbreviations: SE, standard error; CI, confidence interval; srv, servings

Multilevel models were conducted with Stata 13.1 package with the maximum likelihood option and corrected missing data using the inverse probability weighted method (n=516 for purchasing and n=226 for consumption). Multilevel models are good approach to be used under the missing at random assumption, as it models both the means and the random effect jointly.

In all models: treatment group was coded as comparison (0) and intervention (1); time was coded as baseline (0) and post-intervention (1); standard errors were corrected for clustering for repeated measures from the same individual and BHCK neighborhood (from 1 to 30).

Mean difference in change over time for intervention compared to control adult caregiver

Food acquisition frequency (daily) was estimated via a pre-defined list containing 100% fruit juice, apples, bananas, oranges, other fresh fruits, frozen fruits, canned fruits, fresh vegetables, frozen vegetables, and canned vegetables (excluding potatoes). Adults reported frequency of purchasing these items in the previous 30 days.

Fruit and Vegetable intakes were estimated via the Quick Fruit and Vegetable Screener from the National Cancer Institute’s Eating at America’s Table Study (EATS) study. Sample size (n) = 226

Association between food-related behaviors and exposure to the BHCK intervention

The results of the TTE analysis are presented on Table 5 (overall exposure score) and Table 6 (BHCK components exposure score). For each one-point increase in exposure score, there was a 0.24 increase in mean daily fruit serving intake over time (0.24 ± 0.11; 95% CI 0.04; 0.47). There was no statistical difference in the effect of exposure moderated by the two BHCK Waves (Supplemental Table 2).

Table 5:

Association between exposure to B’more Healthy Communities for Kids intervention on change in food-related behaviors and fruit and vegetable consumption among low-income African American adult caregivers: Treatment-on-the-Treated-Effect analysis

| Change in food-related behaviors and fruit and vegetable intakea,b | Total Exposure Scored |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SE | 95% CI | |

| Healthful food acquisition score (daily frequency) | 0.01 | 0.03 | −0.07; 0.07 |

| Unhealthful food acquisition score (daily frequency) | 0.06 | 0.06 | −0.06; 0.17 |

| Frequency of home food preparation (days) | 1.13 | 1.50 | −1.69; 4.21 |

| Healthful cooking methods score | −0.02 | 0.05 | −0.11; 0.09 |

| Daily total fruit consumption (servings)c | 0.24* | 0.11 | 0.04; 0.47 |

| Daily total vegetable consumption (servings)c | −0.81 | 0.07 | −0.22; 0.06 |

| Daily total fruit and vegetable consumption (servings)c | 0.16 | 0.10 | −0.11; 0.33 |

Abbreviation: SE, bootstrapped standard error; CI, bias corrected confidence interval

Change from pre- to post-intervention evaluation, n=370

Multiple linear regression models with bootstrap variance (2000 replications) and clustered by BHCK zone, controlled for adult caregiver’s age, sex, income, and household size

Fruit and Vegetable intakes were estimated via the Quick Fruit and Vegetable Screener from the National Cancer Institute’s Eating at America’s Table Study (EATS) study. Sample size (n) = 184

Mean total exposure score: 1.1 (observed range: 0–6.7)

Statistically significant at p<0.05

Table 6:

Association between exposure to B’more Healthy Communities for Kids intervention components and change in food-related behaviors and fruit and vegetable consumption among low-income African American adult caregivers: Treatment-on-the-Treated-Effect analysis

| Change in food-related behaviors and fruit and vegetable intakea,b | Communication Materials Exposure Scored | Food Environment Exposure Scoree | Social Media Exposure Scoref | Text Messaging Exposure Scoreg | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SE | 95% C.I. | Mean | SE | 95% C.I. | Mean | SE | 95% C.I. | Mean | SE | 95% C.I. | |

| Healthful food acquisition score (daily frequency) | 0.01 | 0.06 | −0.14; 0.10 | 0.02 | 0.10 | −0.19; 0.19 | 0.28 | 0.12 | −0.16; 0.73 | 0.03 | 0.04 | −0.04; 0.12 |

| Unhealthful food acquisition score (daily frequency) | 0.03 | 0.11 | −0.17; 0.23 | 0.16 | 0.19 | −0.21; 0.56 | 0.47* | 0.23 | 0.02; 0.93 | −0.02 | 0.04 | −0.10; 0.06 |

| Frequency of home food preparation (days) | 3.31 | 2.60 | −1.94; 8.59 | 2.52 | 2.80 | −1.98; 9.51 | 1.41 | 10.20 | −18.54; 21.35 | −0.54 | 1.53 | −3.55; 2.47 |

| Healthful cooking methods score | 0.03 | 0.08 | −0.14; 0.19 | 0.07 | 0.18 | −0.31; 0.15 | −0.37 | 0.35 | −1.07; 0.33 | −0.02 | 0.05 | −0.12; 0.08 |

| Daily total fruit consumption (servings)c | 0.22 | 0.17 | −0.06; 0.59 | 0.55 | 0.34 | −0.26; 0.10 | 3.16* | 0.92 | 1.33; 4.99 | 0.02 | 0.15 | −0.30; 0.31 |

| Daily total vegetable consumption (servings)c | −0.14 | 0.11 | −0.38; 0.06 | −0.15 | 0.18 | −0.54; 0.18 | −0.21 | 0.93 | −2.02; 1.48 | −0.01 | 0.13 | −0.26; 0.25 |

| Daily total fruit and vegetable consumption (servings)c | 0.07 | 0.18 | −0.31; 0.43 | 0.40 | 0.39 | −0.71; 0.95 | 2.94* | 1.01 | 0.96; 4.93 | 0.25 | 0.21 | −0.39; 0.44 |

Abbreviation: SE, bootstrapped standard error; CI, bias corrected confidence interval

Change from pre- to post-intervention evaluation, n=370

Multiple linear regression models with bootstrap variance (2000 replications) and clustered by BHCK zone, controlled for adult caregiver’s age, sex, income, and household size

Fruit and Vegetable intakes were estimated via the Quick Fruit and Vegetable Screener from the National Cancer Institute’s Eating at America’s Table Study (EATS) study. Sample size (n) = 184

Communication material score mean: 0.6 (observed range: 0–3.1);

Food environment intervention exposure score mean: 0.3 (observed range: 0–3.1);

Social media/texting exposure score mean: 0.2 (observed range: 0–2);

Texting exposure score mean: 1.1 (observed range 0–3)

Statistically significant behavioral change at p<0.05; Omega-squared (ω2) estimates of the proportion of the variance in the unhealthful food acquisition, fruit, and fruit and vegetable intake which is due to the variance in the social media exposure score (effect size) = 0.005; 0.04; 0.02, respectively.

When exploring the exposure score by intervention component, we found a positive change in food-related behaviors among adult caregivers correlated with a greater exposure to the BHCK social media component. For each one-point increase in social media exposure score (e.g., following an additional social media account or seeing an additional post online), there was an increased three servings of daily fruit intake (3.16 ± 0.92; 95% CI 1.33; 4.99) and daily FV intake (2.94 ± 1.01; 95% CI 0.96; 4.93). A higher social media exposure score was also associated with increased unhealthful daily food acquisition score (0.47 ± 0.23; 95% CI 0.02; 0.93). Effect sizes estimated by omega-squared showed a higher proportion of the variance in fruit intake explained by the variance in the social media exposure score (ω2=0.04), than the effect size of unhealthful food acquisition (ω2=0.0005) (Table 6 and Supplemental Table 3). Our sensitivity analysis conducted with multivariate logistic regression models showed that the direction of association and the estimated effect sizes given by standardized odds ratios were similar as the linear regression models (Supplemental Table 3).

Discussion

BHCK tested a 6- to 8-month community-based intervention designed for low-income African-American families to improve access and consumption of healthful foods. The ATE analysis did not show evidence of significant improvement in food acquisition, preparation, and FV consumption among adult caregivers. However, the TTE analysis (‘dose received’) showed a statistically significant increase in daily intake of fruits among participants who reported higher exposure to the intervention. In addition, we used the exposure score to partition out the change in food-related behaviors influenced by different BHCK intervention components and found that the social media component had a positive correlation with improved daily fruit intake, daily FV intake, and unexpectedly with higher frequency of unhealthful food acquisition.

Mixed results have been observed among the few childhood obesity interventions that assessed behavioral change at the caregiver-level, mainly due to differences in level of caregiver participation in the intervention, varied quality of outcome measurements, and quality of intervention implementation. The Screen-Time Weight-loss Intervention delivered face-to-face in households by community workers to youth (9–12 years old) and their caregivers, did not find an impact on BMI nor physical activity levels of primary caregivers.(46) Authors attributed the null effects due to low adherence to the fidelity of the initial implementation protocol.(46; 47) The multilevel multicomponent community-based Switch what you Do, View, and Chew intervention that targeted children 9–11 years old attending 10 schools in Minnesota and Iowa, U.S., found a significant increase in intake of self-reported FV weekly servings among intervention caregivers.(48) The Shape Up Somerville community-based participatory research reported decreases in BMI among intervention caregivers; however, height and weight were self-reported, and no behavioral outcome was assessed.(21)

The null impact of BHCK on caregiver’s behavior may be attributed to 1) the low intervention exposure experienced by caregivers; and/or 2) the contamination of the intervention activities among comparison caregivers, thus attenuating the average effect towards the null in the ATE analysis.(49) Other community-based interventions have also attributed limited effects resulting from an ATE approach to the low level of engagement informed by TTE analysis. The Switch intervention observed greater change in weekly FV intake among caregivers who were more involved in the intervention, compared to those who were less involved.(48) Another community-based childhood obesity prevention intervention - The Healthy Families Study – found positive health-related outcomes among families with higher exposure to the intervention (TTE), and null results with ATE analyses.(49) Authors attributed the null effects from the primary impact analysis to low participation in community classes.(49)

In our study, low exposure might be explained by the fact that the BHCK study sample were not required to attend community-based activities (i.e., taste tests, point-of-purchase promotions, and nutrition education sessions in corner stores, carryout restaurants and recreation centers). Furthermore, we did not expect the intervention study sample to receive the same dose of the intervention across all components. Conversely, only adult caregivers in the intervention arm were asked to join the text messaging program at study enrollment and were given directions of how to follow BHCK social media platforms. However, both social media platforms were public, meaning that any individual could follow the social media accounts (Facebook and Instagram), which increased the likelihood of exposure contamination among participants in the control group, and that may have attenuated differences between study arms. On the other hand, the usage of a tailored approach may help explain behavior changes observed among only those with higher levels of exposure to the social media component. The social media and text messaging component employed goal-setting bi-directional communication strategies. Social media pages were public accounts with daily posts that mirrored the content of text messaging and other BHCK components, and participants were encouraged to share online achievement, barriers, tips, and resources. The higher reach and intensity of the social media component may help explain the positive correlation with food-related behaviors, compared to the other intervention components.

The increase in fruit intake was driven by a one-point increase in social media exposure, which corresponds to following at least one of the study social media accounts or seeing four or more posts. Similar to our findings, The Food Hero study - a social media campaign targeted at SNAP-eligible families with children - found increased positive beliefs about FV among participants.(50) Although previous studies have tested social media approaches for behavioral interventions(51; 52; 53; 54), to our knowledge, BHCK was the first study to combine these strategies into a multilevel multicomponent community-based nutrition intervention. The use of social media to provide a platform for actionable information and social support for families with children has been recommended in the obesity prevention literature(54; 55; 56) and is being further tested in ongoing community-based trials.(57; 58)

Given the low consumption of FV among the U.S. population(59), especially among low-income African-American individuals(60; 61), it is necessary to explore innovative strategies to promote healthier dietary intake. Although we found a positive correlation between self-reported exposure to the BHCK social media component with FV, the main increase in intake was in fruits, and not vegetables. Fruits are sweeter, often do not required any preparation (consumed raw), and generally consumed and accepted as a snack, drink, and dessert(62), whereas vegetables often require cooking, and are more typically consumed as part of meals.(63) Future studies should consider the impact of the intervention on fruit and vegetables as separate and different food types.(64; 65)

Unexpectedly, we found that an increased frequency of unhealthful food acquisition was correlated with greater exposure to the BHCK social media component. One potential reason for this may be that adults exposed to BHCK social media may have also been exposed to online advertising for energy-dense, nutrient-poor foods and mobile marketing food campaigns.(66; 67) Prior studies have demonstrated a negative effect of online food advertisement on youth’s consumption of healthful foods(68; 69), and similar trends were found for adult caregivers.(70; 71) More research needs to be conducted to examine the relationship between public health social media campaigns and advertising exposure.

Limitations of this study should be noted. The survey was administered to self-identified caregivers, under the assumption that they acquire most of the food and cook for their family members. However, some caregivers may not be the primary food purchasers in their households. Also, our measure of frequency of food purchased did not take into consideration the quality or quantity of the acquired food/beverage. Future child-focused interventions should conduct more comprehensive food and nutrient assessments of adult caregivers. The loss of observations over the course of the study is also a limitation, despite our efforts to avoid drop-outs during the course of the study (e.g., eligibility criteria included intent to stay within the study areas over the next two years, multiple attempts were made to contact the families over the phone - and if not possible to reach over the phone, household visits were done to conduct follow-up surveys). Thus, to address potential selection bias, inverse probability weighting (IPW) was employed in the analysis to correct for the effects of missing data.(37) Another study limitation might be the risk of social desirability bias by treatment assignment, reflected in the self-reported intervention exposure questionnaire. However, our questionnaire included red-herring questions to improve validity, and data collectors were masked to intervention treatment assignment. We were not able to directly assess individual’s social media participation, as individuals often display nicknames instead of names used on their profile pages, which precluded our efforts to cross check the self-reported information. In addition, although we utilized a computer software to manage our text messaging program, some people may have not received the texts (because of low credit balance on their phone) or may have not read the text sent.

BHCK was an intervention that sought to modify the out of school community food environment and engage families through social media, but did not implement a component to improve the household food environment. Therefore, future studies aiming at preventing childhood obesity among underserved communities should consider intervening in both community and household food environments. Lastly, although multilevel, multicomponent interventions have broader reach than single-level approaches, they have the additional challenge of achieving low exposure.(72) Hence, conducting a detailed process evaluation during implementation is essential for understanding to what extent the target population is receiving the program.

Conclusions

The BHCK intervention is one of the few child-focused obesity prevention interventions to measure treatment effects at the caregiver-level in terms of food acquisition, preparation, and FV consumption, and the first study to attempt to evaluate a dose response relationship in terms of exposure level to the different intervention components. Although our ATE analysis including all trial participants demonstrated no effect of BHCK on food-related behaviors, we were able to demonstrate that a higher level of exposure to the BHCK intervention was associated with improvements in daily fruit intake among adult caregivers, particularly among those with higher exposures to the social media component. Our study highlights the importance of optimal dose and intensity of community-based intervention activities to achieve intended behavioral changes, and the possibility of intervention contamination between intervention and comparison participants in community-based behavior interventions. Future multilevel multicomponent community-based interventions should engage caregivers more in the intervention, enroll larger samples, as well as assess engagement and exposure to intervention activities during the trial to enhance likelihood of intervention effectiveness. Social media (Facebook, Instagram) may be a promising tool to improve reach and engage caregiver participants in multilevel childhood obesity interventions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

We would like to thank the families interviewed and the following students, staff, and volunteers who assisted in the BHCK data collection, including: Anna Kharmats, Cara F. Ruggiero, Kelleigh Eastman, Melissa Sattler, JaWanna Henry, Jenny Brooks, Selma Pourzal, Teresa Schwendler, Gabriela Vedovato, Sarah Rastatter, Kate Perepezko, Lisa Poirier, Thomas Eckmann, Maria Jose Mejia, Yeeli Mui, Priscila Sato, Bengucan Gunen, Ivory Loh, Courtney Turner, Whitney Kim, Shruti Patel, Ellen Sheehan, Ryan Wooley, Gabrielle Headrick, Donna Dennis, Elizabeth Chen, Kiara James, Latecia Williams, Harmony Farner, Rena Hamzey, Nandita Krishnan, Alexandra Ross.

Financial Support: Research reported in this publication was supported by the Global Obesity Prevention Center (GOPC) at Johns Hopkins, and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) and the Office of the Director, National Institutes of Health (OD) under award number U54HD070725. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NICHD or the Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research. This work was also funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (1U48DP000040, SIP 14–027). ACBT is supported by a doctoral fellowship from the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development CNPq (GDE: 249316/2013–7).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None

Ethical Standards Disclosure

This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving human subjects were approved by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Institutional Review Board (IRB #00004203). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

References

- 1.Swinburn BA, Sacks G, Hall KD et al. (2011) The global obesity pandemic: shaped by global drivers and local environments. Lancet 378, 804–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kirkpatrick SI, Dodd KW, Reedy J et al. (2012) Income and Race/Ethnicity Are Associated with Adherence to Food-Based Dietary Guidance among US Adults and Children. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics 112, 624–635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martinez Steele E, Baraldi LG, Louzada ML et al. (2016) Ultra-processed foods and added sugars in the US diet: evidence from a nationally representative cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 6, e009892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bleich SN, Wang YC, Wang Y et al. (2009) Increasing consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages among US adults: 1988–1994 to 1999–2004. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 89, 372–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Piernas C, Popkin BM (2010) Snacking Increased among US Adults between 1977 and 2006. Journal of Nutrition 140, 325–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson MM, Reedy J, Krebs-Smith SM (2016) American Diet Quality: Where It Is, Where It Is Heading, and What It Could Be. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics 116, 302–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rehm CD, Penalvo JL, Afshin A et al. (2016) Dietary Intake Among US Adults, 1999–2012. Jama-J Am Med Assoc 315, 2542–2553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Black C, Moon G, Baird J (2014) Dietary inequalities: what is the evidence for the effect of the neighbourhood food environment? Health & place 27, 229–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Larson NI, Story MT, Nelson MC (2009) Neighborhood environments: disparities in access to healthy foods in the U.S. Am J Prev Med 36, 74–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drewnowski A, Aggarwal A, Cook A et al. (2016) Geographic disparities in Healthy Eating Index scores (HEI-2005 and 2010) by residential property values: Findings from Seattle Obesity Study (SOS). Prev Med 83, 46–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gordon-Larsen P, Nelson MC, Page P et al. (2006) Inequality in the built environment underlies key health disparities in physical activity and obesity. Pediatrics 117, 417–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lobstein T, Jackson-Leach R, Moodie ML et al. (2015) Child and adolescent obesity: part of a bigger picture. Lancet 385, 2510–2520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roberto CA, Swinburn B, Hawkes C et al. (2015) Patchy progress on obesity prevention: emerging examples, entrenched barriers, and new thinking. The Lancet 385, 2400–2409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler a et al. (1988) An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health education quarterly 15, 351–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hung L-S, Tidwell DK, Hall ME et al. (2015) A Meta-Analysis of School-Based Obesity Prevention Programs Demonstrates Limited Efficacy of Decreasing Childhood Obesity. Nutrition Research 35, 229–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gittelsohn J, Kumar MB (2007) Preventing childhood obesity and diabetes: is it time to move out of the school? Pediatric Diabetes 8, 55–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bleich SN, Segal J, Wu Y et al. (2013) Systematic Review of Community-Based Childhood Obesity Prevention Studies. Pediatrics 132, e201–e210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Waters E, de Silva-Sanigorski A, Hall BJ et al. (2011) Interventions for preventing obesity in children. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews, CD001871–CD001871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heim S, Bauer KW, Stang J et al. (2011) Can a Community-based Intervention Improve the Home Food Environment? Parental Perspectives of the Influence of the Delicious and Nutritious Garden. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 43, 130–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Golan M, Crow S (2004) Targeting parents exclusively in the treatment of childhood obesity: long-term results. Obes Res 12, 357–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coffield E, Nihiser AJ, Sherry B et al. (2015) Shape Up Somerville: change in parent body mass indexes during a child-targeted, community-based environmental change intervention. American journal of public health 105, e83–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haerens L, Deforche B, Maes L et al. (2006) Evaluation of a 2-year physical activity and healthy eating intervention in middle school children. Health Educ Res 21, 911–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pollard SL, Zachary DA, Wingert K et al. (2014) Family and Community Influences on Diabetes-Related Dietary Change in a Low-Income Urban Neighborhood. The Diabetes Educator 40, 462–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gittelsohn J, Steeves E, Mui Y et al. (2014) B’More Healthy Communities for Kids: Design of a Multi-Level Intervention for Obesity Prevention for Low-Income African American Children. BMC public health 14, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gittelsohn J, Trude AC, Poirier L et al. (2017) The Impact of a Multi-Level Multi-Component Childhood Obesity Prevention Intervention on Healthy Food Availability, Sales, and Purchasing in a Low-Income Urban Area. International journal of environmental research and public health 14, 1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trude ACB, Kharmats AY, Jones-Smith JC et al. (2018) Exposure to a multi-level multi-component childhood obesity prevention community-randomized controlled trial: patterns, determinants, and implications. Trials 19, 287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mikkelsen BE, Novotny R, Gittelsohn J (2016) Multi-Level, Multi-Component Approaches to Community Based Interventions for Healthy Living—A Three Case Comparison. International journal of environmental research and public health 13, 1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glasgow RE, Klesges LM, Dzewaltowski DA et al. (2004) The future of health behavior change research: What is needed to improve translation of research into health promotion practice? Annals of Behavioral Medicine 27, 3–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sedgwick P (2015) Intention to treat analysis versus per protocol analysis of trial data. Brit Med J 350, h681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walker RE, Keane CR, Burke JG (2010) Disparities and access to healthy food in the United States: A review of food deserts literature. Health & place 16, 876–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Subar AF, Thompson FE, Kipnis V et al. (2001) Comparative Validation of the Block, Willett, and National Cancer Institute Food Frequency Questionnaires : The Eating at America’s Table Study. American Journal of Epidemiology 154, 1089–1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yaroch AL, Tooze J, Thompson FE et al. (2012) Evaluation of three short dietary instruments to assess fruit and vegetable intake: the National Cancer Institute’s food attitudes and behaviors survey. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics 112, 1570–1577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suratkar S, Gittelsohn J, Song H-J et al. (2010) Food insecurity is associated with food-related psychosocial factors and behaviors among low-income African American adults in Baltimore City. J Hunger Environ Nutr 5, 100–119. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gittelsohn J, Franceschini MCT, Rasooly IR et al. (2008) Understanding the Food Environment in a Low-Income Urban Setting: Implications for Food Store Interventions. Journal of Hunger & Environmental Nutrition 2, 33–50. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vedovato GM, Surkan PJ, Jones-Smith J et al. (2016) Food insecurity, overweight and obesity among low-income African-American families in Baltimore City: associations with food-related perceptions. Public health nutrition 19, 1405–1416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gittelsohn J, Anliker Ja, Sharma S et al. (2006) Psychosocial Determinants of Food Purchasing and Preparation in American Indian Households. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 38, 163–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fitzmaurice GM, Laird NM, Ware JH (2012) Applied Longitudinal Analysis. Chicester, UNITED STATES: John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guan W (2003) From the help desk: Bootstrapped standard errors. Stata Journal 3, 71–80. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Amemiya A (1978) The Estimation of a Simultaneous Equation Generalized Probit Model. Econometrica 46, 1193. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schwendler T, Shipley C, Budd N et al. (2017) Development and Implementation: B’more Healthy Communities for Kids Store and Wholesaler Intervention. Health Promotion Practice, 1524839917696716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perepezko K, Tingey L, Sato P et al. (2018) Partnering with carryouts: implementation of a food environment intervention targeting youth obesity. Health Educ Res 33, 4–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sato PM, Steeves EA, Carnell S et al. (2016) A youth mentor-led nutritional intervention in urban recreation centers: a promising strategy for childhood obesity prevention in low-income neighborhoods. Health Education Research 31, 195–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Loh IH, Schwendler T, Trude ACB et al. (2018) Implementation of Text-Messaging and Social Media Strategies in a Multilevel Childhood Obesity Prevention Intervention: Process Evaluation Results. Inquiry 55, 46958018779189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nam CS, Ross A, Ruggiero C et al. (2018) Process Evaluation and Lessons Learned From Engaging Local Policymakers in the B’More Healthy Communities for Kids Trial. Health Education & Behavior 00, 1090198118778323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ruggiero CF, Poirier L, Trude ACB et al. (2018) Implementation of B’More Healthy Communities for Kids: process evaluation of a multi-level, multi-component obesity prevention intervention. Health Educ Res. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maddison R, Marsh S, Foley L et al. (2014) Screen-Time Weight-loss Intervention Targeting Children at Home (SWITCH): a randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 11, 111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Epstein LH, Roemmich JN, Robinson JL et al. (2008) A randomized trial of the effects of reducing television viewing and computer use on body mass index in young children. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 162, 239–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gentile DA, Welk G, Eisenmann JC et al. (2009) Evaluation of a multiple ecological level child obesity prevention program: Switch what you Do, View, and Chew. BMC Med 7, 49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hull PC, Buchowski M, Canedo JR et al. (2016) Childhood obesity prevention cluster randomized trial for Hispanic families: outcomes of the healthy families study. Pediatr Obes. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tobey LN, Manore MM (2014) Social Media and Nutrition Education: The Food Hero Experience. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 46, 128–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.O’Brien LM, Palfai TP (2016) Efficacy of a brief web-based intervention with and without SMS to enhance healthy eating behaviors among university students. Eating Behaviors 23, 104–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Naslund JA, Aschbrenner KA, Marsch LA et al. (2018) Facebook for Supporting a Lifestyle Intervention for People with Major Depressive Disorder, Bipolar Disorder, and Schizophrenia: an Exploratory Study. Psychiatr Q 89, 81–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tobey LN, Koenig HF, Brown NA et al. (2016) Reaching Low-Income Mothers to Improve Family Fruit and Vegetable Intake: Food Hero Social Marketing Campaign-Research Steps, Development and Testing. Nutrients 8, E562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.George KS, Roberts CB, Beasley S et al. (2016) Our Health Is in Our Hands: A Social Marketing Campaign to Combat Obesity and Diabetes. American Journal of Health Promotion 30, 283–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.O’Kane C, Wallace A, Wilson L et al. (2018) Family-Based Obesity Prevention: Perceptions of Canadian Parents of Preschool-Age Children. Can J Diet Pract Res 79, 13–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Medairos R, Kang V, Aboubakare C et al. (2017) Physical Activity in an Underserved Population: Identifying Technology Preferences. Journal of Physical Activity & Health 14, 3–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gittelsohn J, Jock B, Redmond L et al. (2017) OPREVENT2: Design of a multi-institutional intervention for obesity control and prevention for American Indian adults. BMC public health 17, 105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tomayko EJ, Prince RJ, Cronin KA et al. (2017) Healthy Children, Strong Families 2: A randomized controlled trial of a healthy lifestyle intervention for American Indian families designed using community-based approaches. Clin Trials 14, 152–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Committee DGA (2015) Scientific report of the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee, advisory report to the Secretary of Health and Human Services and the Secretary of Agriculture. Washington, DC: U.S.: US Department of Agriculture and US Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Robinson T (2008) Applying the Socio-ecological Model to Improving Fruit and Vegetable Intake Among Low-Income African Americans. Journal of Community Health 33, 395–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Di Noia J, Monica D, Cullen KW et al. (2016) Differences in Fruit and Vegetable Intake by Race/Ethnicity and by Hispanic Origin and Nativity Among Women in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children, 2015. Preventing Chronic Disease 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Burg J, de Vet E, de Nooijer J et al. (2006) Predicting fruit consumption: Cognitions, intention, and habits. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 38, 73–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Anderson AS, Cox DN, McKellar S et al. (1998) Take Five, a nutrition education intervention to increase fruit and vegetable intakes: impact on attitudes towards dietary change. Br J Nutr 80, 133–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Appleton KM, Hemingway A, Saulais L et al. (2016) Increasing vegetable intakes: rationale and systematic review of published interventions. Eur J Nutr 55, 869–896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Glasson C, Chapman K, James E (2011) Fruit and vegetables should be targeted separately in health promotion programmes: differences in consumption levels, barriers, knowledge and stages of readiness for change. Public health nutrition 14, 694–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zimmerman FJ (2011) Using Marketing Muscle to Sell Fat: The Rise of Obesity in the Modern Economy. Annu Rev Publ Health 32, 285–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Montgomery KC, Chester J, Grier SA et al. (2012) The new threat of digital marketing. Pediatr Clin North Am 59, 659–675, viii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Harris JL, Speers SE, Schwartz MB et al. (2012) US Food Company Branded Advergames on the Internet: Children’s exposure and effects on snack consumption. Journal of Children and Media 6, 51–68. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Boyland EJ, Nolan S, Kelly B et al. (2016) Advertising as a cue to consume: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of acute exposure to unhealthy food and nonalcoholic beverage advertising on intake in children and adults. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 103, 519–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dixon H, Scully M, Wakefield M et al. (2011) Parent’s responses to nutrient claims and sports celebrity endorsements on energy-dense and nutrient-poor foods: an experimental study. Public health nutrition 14, 1071–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pettigrew S, Tarabashkina L, Roberts M et al. (2013) The effects of television and Internet food advertising on parents and children. Public health nutrition 16, 2205–2212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Heerman WJ, JaKa MM, Berge JM et al. (2017) The dose of behavioral interventions to prevent and treat childhood obesity: a systematic review and meta-regression. The international journal of behavioral nutrition and physical activity 14, 157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.