Abstract

Objective:

To quantitatively and qualitatively describe the patient experience for stable patients presenting with miscarriage to the emergency department (ED) or ambulatory clinics.

Methods:

We present a sub-analysis of a mixed-methods study from 2016 on factors influencing miscarriage treatment decision-making among clinically stable patients. Fifty-four patients were evaluated based on location of miscarriage care (ED or ambulatory-only), and novel parameters were assessed including timeline (days) from presentation to miscarriage resolution, number of health system interactions, and number of specialty-based provider care teams seen. We explored themes around patient satisfaction through in-depth narrative interviews.

Results:

Median time to miscarriage resolution was 11 days (range 5-57) (ED) and 8 days (range 0-47) (ambulatory-only). We recorded a mean of 4.4±1.4 (ED) and 3.0±1.2 (ambulatory-only) separate care teams and a median of 13 (range 8-20) (ED) and 19 (range 8-22) (ambulatory-only) health system interactions. Patients seeking care in the ED were younger (28.3 vs. 34.0, OR 5.8, 95% CI 1.8-18.7), more likely to be of Black race (28.3 vs. 34.0, OR 3.3, 95% CI 1.1-10.0), uninsured or insured through Medicaid (16 vs. 6, OR 6.8, 95% CI 2.1-22.5), and more likely to meet criteria for post-traumatic stress disorder compared to ambulatory-only patients (10 vs. 3, OR 6.0, 95% CI 1.5-23.4). Patients valued diagnostic clarity, timeliness, and individualized care. We found that ED patients reported a lack of clarity surrounding their diagnosis, inefficient care, and a mixed experience with health care provider sensitivity. In contrast, ambulatory-only patients described a streamlined and sensitive care experience.

Conclusion:

Patients seeking miscarriage care in the ED were more likely to be socioeconomically and psychosocially vulnerable and were less satisfied with their care compared to those seen in the ambulatory setting alone. Expedited evaluation of early pregnancy problems, with attention to clear communication and emotional sensitivity, may optimize the patient experience.

Précis

Stable miscarriage patients presenting to the emergency department have baseline socioeconomic disadvantages and are less satisfied than those presenting to ambulatory clinics.

Introduction

Miscarriage, or early pregnancy loss, is a common pregnancy complication, affecting approximately one in five pregnancies in the United States (1, 2). Most miscarriages occur within the first trimester (1), and potentially before the usual time of the first prenatal appointment. Patients with concerns about a potential miscarriage, perhaps prompted by bleeding after a positive pregnancy test, present for care in emergency departments at a rate of approximately 500,000 each year in the United States (3). The health care setting in which a patient receives the evaluation, diagnosis, and management of an early pregnancy complication like miscarriage can influence her experience (4). People often suffer stress and grief with miscarriage (5), and clinicians caring for these patients have the opportunity to mitigate, rather than exacerbate, these negative outcomes (6, 7).

Patients may choose the emergency department over the ambulatory setting for a variety of reasons, including access and affordability, level of perceived clinical urgency, or clinician recommendation (8). When a nonviable pregnancy is diagnosed in early pregnancy, a patient may wait for natural tissue expulsion or select active management with a procedure or medication. The choice between expectant or active management often hinges on how important the timing of the resolution of the miscarriage is to the patient (9). We therefore sought to characterize the timeline from presentation to resolution in patients with miscarriage seeking care in emergency and ambulatory settings, as well as patient satisfaction with miscarriage management among these two groups.

Methods

We performed a secondary analysis of a convergent exploratory mixed-methods study: the Miscarriage Management Choice Study, which examined factors influencing miscarriage treatment decision-making among clinically stable patients, the primary results of which have been described previously (9). For this secondary analysis, we divided the study sample into two groups: those who sought care in the emergency department (ED) and those whose care was limited to the ambulatory setting (ambulatory-only). The ED group included patients treated exclusively in the ED as well as patients initially seeking care in the ED who were later seen in ambulatory clinics.

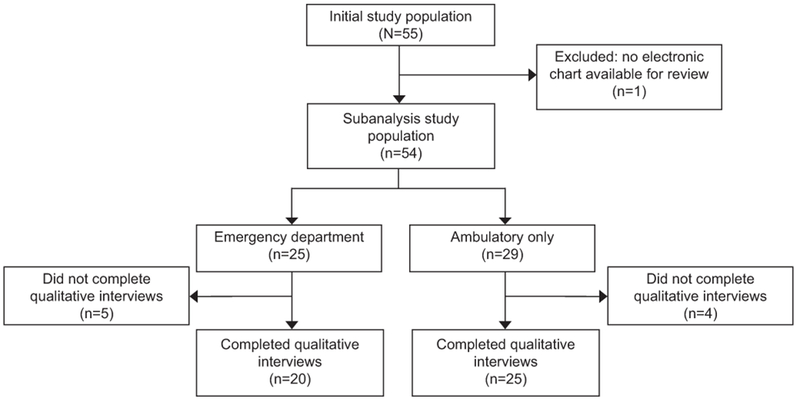

Fifty-five patients were recruited at the time of miscarriage diagnosis (after receiving a diagnosis, but before treatment) at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania between from January 2014 to January 2015, from the hospital ED and outpatient clinical practices. Eligible participants were at least 18 years old and English-speaking, had ultrasound diagnosis of an anembryonic gestation or embryonic or fetal demise in the first trimester (5-12 completed weeks of gestation) confirmed by two clinicians, and were clinically stable with a closed cervical os. Participants completed validated baseline questionnaires that included demographics and psychometric measures, as well as open-ended, semi-structured interviews within seven days of enrollment. We included 54 participants in this secondary analysis, as one participant did not have an electronic medical record data available for chart extraction (Figure 1). All study activities were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Pennsylvania.

Fig. 1.

Study participant data flowchart.

Forty-five interviews were required to reach thematic saturation around the outcome of interest (miscarriage management choice) from the primary study. Interview transcripts were entered into Nvivo 10 (QSR International, Melbourne Australia), a qualitative software package, and coded using a modified grounded theory approach. Two researchers independently reviewed transcripts to create systematic coding categories and inter-coding reliability was assessed by comparing 20% of transcripts. The median Kappa was 0.81 and agreement was 96%.

For this secondary analysis, quantitative outcomes included: time to miscarriage resolution (days from initial patient contact regarding early pregnancy concern at the study institution to final telephone or in-person health care system interaction during the observed pregnancy, including ultrasound or laboratory follow-up after medical management, or post-operative follow-up if indicated after surgical management); number of health care system interactions (defined as in-person or telephone encounters with a clinic or hospital service within the study institution, extracted from the electronic medical record); and number of care teams (distinct ambulatory clinics or hospital services). Data included in this analysis were limited to those recorded in the Penn Medicine electronic medical record.

We evaluated demographics and psychometric measures, including the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), the Beck Anxiety Inventory, the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), and the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist-Civilian (PCL-C), for all participants using standard descriptive statistics. For the baseline comparison of the ED and ambulatory-only groups, we used Pearson chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests to compare categorical scores as well as Student’s t-tests and Wilcoxon rank sum tests for continuous variables. Variables that differed with significance p<0.10 were considered for a multivariable model using backwards selection. We used a Cox proportional-hazards model to describe the association of these predictors with the time to miscarriage resolution. All quantitative analyses were completed using Stata 14.2 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

In our qualitative analysis, we first analyzed transcribed interview data across the entire cohort using a grounded theory approach along previously coded categories, or nodes, from the primary study. We selected all nodes relevant to patient experience and satisfaction (“Accessing care,” “Satisfaction and facilitation,” “Provider interactions,” and “Dissatisfaction and barriers”) and two researchers independently first identified and then agreed upon themes of patient satisfaction that emerged from the transcript segments. We then stratified these data into ED and ambulatory-only groups in order to examine the differences in these themes.

Results

Our overall study population (n=54) was socio-demographically diverse. Most participants were parous (n=33, 61%). Patients seeking care in the ED were younger (28.3 vs. 34.0, OR 5.8, 95% CI 1.8-18.7), more likely to be of Black race (16 vs. 11, OR 3.3, 95% CI 1.1-10.0), and more likely to be without insurance or insured through Medicaid (16 vs. 6, OR 6.8, 95% CI 2.1-22.5) compared to patients who did not seek care in the ED (Table 1). Additionally, patients using the ED were significantly more likely to meet criteria for post-traumatic stress disorder (10 vs. 3, OR 6.0, 95% CI 1.5-23.4; Table 1).

Table 1:

Demographics of patients presenting for miscarriage care by Emergency Department use

| Full Group N = 54 | Use of ED N = 25 | No use of ED N = 29 | OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| <=30 | 21 (39) | 15 (60) | 6 (21) | - |

| 30+ | 33 (61) | 10 (40) | 23 (79) | 5.6 (1.8-18.7) |

| Race | ||||

| African-American | 27 (50) | 16 (67) | 11 (38) | - |

| Other | 27 (50) | 8 (33) | 18 (63) | 3.3 (1.1-10.0) |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic | 2 (4) | 2 (8) | 0 (0) | Not applicable* |

| Non-Hispanic | 52 (96) | 23 (92) | 29 (100) | |

| Insurance | ||||

| Private | 32 (59) | 9 (36) | 23 (79) | - |

| Other†/None | 22 (41) | 16 (64) | 6 (21) | 6.8 (2.1-22.5) |

| Gravidity | ||||

| 1 | 12 (22) | 4 (16) | 8 (28) | - |

| 2+ | 42 (78) | 21 (84) | 21 (72) | 0.5 (0.6-6.6) |

| Parity | ||||

| 0 | 21 (39) | 9 (36) | 12 (41) | - |

| 1+ | 33 (61) | 16 (64) | 17 (59) | 0.8 (0.3-2.4) |

| Term Deliveries | ||||

| 0 | 23 (43) | 11 (44) | 12 (41) | - |

| 1+ | 31 (57) | 14 (56) | 17 (59) | 1.1 (0.4-3.3) |

| History of elective abortion | ||||

| No | 34 (63) | 13 (52) | 21 (72) | - |

| Yes | 20 (37) | 12 (48) | 8 (28) | 1.6 (0.8-3.2) |

| Previous history of miscarriage | ||||

| No | 34 (63) | 14 (56) | 20 (69) | - |

| Yes | 20 (37) | 11 (44) | 9 (31) | 1.4 (0.7-2.8) |

| Depressed‡ | ||||

| No (less than 16) | 20 (39) | 7 (29) | 13 (46) | - |

| Yes (16 or greater) | 32 (61) | 17 (71) | 15 (54) | 0.5 (0.2-1.5) |

| Anxiety§ | ||||

| Low (0-21) | 41 (79) | 16 (67) | 25 (89) | - |

| Moderate (22-35) | 7 (13) | 5 (21) | 2 (7) | 0.3 (0.0-1.5) |

| High (36 or greater) | 4 (8) | 3 (12) | 1 (4) | 0.2 (0.0-2.2) |

| Stress‖ | ||||

| Yes (less than 13.7) | 36 (69) | 19 (79) | 17 (61) | 2.5 (0.7-8.5) |

| No (13.7 or greater) | 16 (31) | 5 (21) | 11 (39) | - |

| PTSD symptoms | ||||

| No | 39 (75) | 14 (58) | 25 (89) | - |

| Yes | 13 (25) | 10 (42) | 3 (11) | 0.2 (0.0-0.7) |

| Management Method | ||||

| Surgical | 37 (69) | 15 (60) | 22 (76) | - |

| Medical | 15 (27) | 8 (32) | 7 (24) | 0.6 (0.2-2.0) |

| Expectant | 2 (4) | 2 (8) | 0 (0) | Not applicable* |

ED, Emergency Department PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

Data are n(%) or mean±SD.

Unable to model as the “no use of ED” group did not have any Hispanic patients or patients with expectant management.

Medicaid or Medicare, or uninsured

Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) score.

Beck Anxiety Inventory

Perceived Stress Scale

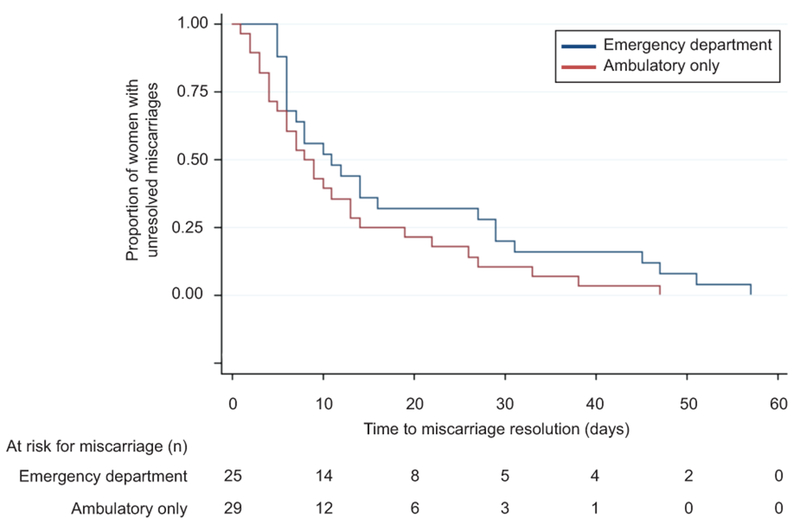

The ED and ambulatory-only patients had a median number of days to resolution of 11 (range 5-57) and 8 (range 0-47) respectively after adjusting for age, race, and insurance; Figure 2. During this period, we recorded a median of 13 (range 8-20) health care system interactions for ED patients and 19 (range 8-22) for ambulatory-only patients. Patients were exposed to an average of 4.4±1.4 (ED) and 3.0±1.2 (ambulatory-only) care teams, including obstetrics and gynecology general and specialty clinics, family medicine, internal medicine, radiology, emergency department, specialty consulting services, and more.

Fig. 2.

Survival curves of time to miscarriage resolution for stable patients seeking care in the emergency department or only in ambulatory settings.

Across the entire cohort, qualitative analysis of satisfaction with miscarriage care revealed the following themes: the balance between certainty of diagnosis and timeliness of treatment, compassion, and individualized attention (Table 2). Participants valued being certain of the outcome of the pregnancy and found it difficult to wait for a final diagnosis. While some participants valued a rapid resolution of the miscarriage, others needed time to process their diagnosis before initiating a treatment. Patients were sensitive to the level of compassion from their health care providers and had mixed experiences, some positive (“[I]t felt like a sister telling me”) and others negative (“[S]he was very ignorant and very disrespectful”). Similarly, patients valued health care providers’ ability to tailor care to each individual, whether through emotional support or time to cope.

Table 2:

Aspects of Care Logistics Valued by Patients Undergoing Miscarriage Evaluation and Management in All Locations

| Theme | Representative Quote(s) |

|---|---|

| Timeliness: How soon the resolution of the pregnancy could be established. | |

| Efficient resolution → | “I didn’t want to drag [it] out any further…I didn’t want to continue what I had already been through with the bleeding…I just wanted it to be over with.” |

| Time to process → | “It just felt a little extreme; I thought I was still pregnant” (in response to having surgery scheduled on the same day as miscarriage diagnosis). |

| Compassion: Perception from patients regarding level of empathy from staff. | |

| Positive → | “The way they said it, it felt like a sister telling me.” “They were very comforting…they made you feel like you were in a safe place; you felt the trust…they took your best interest at heart instead of ‘it’s just a procedure and you’re a patient and we do this every day.’” |

| Negative → | “The last doctor I had…through the procedure…she was very ignorant and very disrespectful.” “I think my original doctor, when I asked him how much time to take off, he said ‘you only need that day; if you really want to pamper yourself, take another one.’ And the pretty severe cramping [I had]…pampering myself sort of made me roll my eyes a little bit.” |

| Flexibility: Willingness of the staff to “bend the rules” for the benefit of the patient experience. | “[My nurse] was asking me if I was ok; [she told me] I could sit here for as long as I needed to.” “I had really expected [my husband] to be next to me. So she let him actually stay in the room, and it felt like she really cared about what I was feeling…I appreciated that she understood that.” |

| Certainty: Value in knowing the outcome of the pregnancy. | “The [waiting] window was really hard…in some ways worse than the news about the miscarriage.” “I couldn’t walk around with, you know, a dead fetus in me. I [needed] to know what was going on.” |

ED: Emergency Department

Our qualitative stratified analysis of ED and ambulatory-only locations of care revealed the following themes: clarity, efficiency, and sensitivity (Table 3). Ambulatory-only patients described a sense of clarity surrounding their diagnosis and treatment options compared to patients who sought care in the ED. Similarly, the ambulatory-only patients observed a sense of efficiency in their care, describing the perceived benefit of same-day treatment options, while ED patients described multiple hand-offs and long wait times. ED patients reported mixed experiences with health care provider sensitivity. One participant recounted her positive experience in the ED: “They were just interested in my overall well-being, like emotional, asked if I was in any pain, what it was that I felt like I needed,” while another described her negative interaction with a radiology technologist, saying, “His attitude just wasn’t there.” The ambulatory-only group more consistently reported a sense of feeling cared for by their health care providers: “It was like they took your best interest at heart instead of, ‘it’s just a procedure, and you’re a patient, and we do this every day.’” Our analysis of these themes found that ED patients reported a lack of clarity surrounding their diagnosis, inefficient care, and a mixed experience with health care provider sensitivity. In contrast, ambulatory-only patients often described a clearer, more streamlined, and sensitive care experience.

Table 3:

Aspects of Care Logistics Valued by Patients Undergoing Miscarriage Evaluation and Management: Stratified by Location

| Emergency Department | Ambulatory-only |

|---|---|

| Sensitivity | |

| “I went to the Emergency Room to get an ultrasound. The [radiology technologist], he was really just—his attitude just wasn’t there. He did the ultrasound […] and he said, the pregnancy’s no more. The fact that he came and just said that, it was kinda like, okay. Well, I know you had sensitivity training and that’s not how you tell anybody anything.” | “She was very sensitive. She kept saying it’s not my fault. It’s nothing I did wrong. […] She seemed very patient. […] She didn’t seem like she was in any rush to kind of end the conversation or get me out of there. She really seemed sensitive to how difficult it must have been for me.” |

| “They were just interested in my overall well-being, like emotional, asked if I was in any pain, what it was that I felt like I needed…They did that both in the ER and in [Family Planning].” | “They did actually like speak to me as if I was a person and not just the patient. They had bedside manners, so they actually—they made you feel like you were in a safe place, you felt the trust. |

| Clarity | |

| “It’s just like, how is it my quants are going up and every time I go to the Emergency Room, they’re still giving me bad news?” | “[T]hey could do more counseling here and really go into our options more, and I felt like that was good.” |

| “[T]hey gave me a piece of paper and told me to go to my GYN or whatever and schedule an appointment.” | “No, I didn’t have any questions because it was pretty much cut and dry. They did explain to me the full outcomes of all three procedures. So I really understood what to expect and what was going to be the outcome.” |

| Efficiency | |

| “It just took a while before I saw anyone. … Of course I knew, they knew, everybody knew that they would have to call Ob/Gyn for a consult, and that they would be the one doing the stuff. … Not only did I have to wait before I was seen, I was in pain, I had no support, but then I had to go through two gynecological exams, which I thought was pretty unnecessary.” | “I feel very fortunate because I have a great relationship with [my Ob/Gyn] and she was the one who discovered that the pregnancy wasn’t viable. She also delivered my daughter. … [She] helped put the wheels in motion for me right away.” |

| “I talked to the doctor that was in charge for—in the [ED], and then the Ob/Gyn came and they both agreed that—yeah. And then the third doctor came that—they had switched shifts and he came in and he spoke with me, and he pretty much had the same—ultimately the same as the other two.” | “They did everything they could to help make it manageable and make it—I guess to provide that closure as soon as possible. Like her taking me that same day. […] So I guess, there’s doctors recognizing that people just want to have closure and not prolong an already painful, horrible situation. To me, it was very important and I appreciated that.” |

ED; Emergency Department

Discussion

In this mixed-methods study, distinct profiles emerged between patients who sought miscarriage care through the ED and patients who sought care exclusively in the outpatient setting. Our observation that patients who presented to the ED were more likely to be young, Black, and underinsured compared to patients who sought care only in ambulatory clinics is consistent with data from the general population in the United States: patients of lower socioeconomic status seek ED care more often than those of higher status (10). Our additional finding that ED patients were more likely to meet criteria for post-traumatic stress disorder reveals that this group was not only socioeconomically but also psychosocially vulnerable.

The ED patient experience was qualitatively associated with greater patient confusion and less satisfaction, similar to other qualitative studies of miscarriage care in the ED where patients reported poor communication, unfriendly environment, and a lack of emotional support (11, 12). Participants who sought care in the ED had longer time to miscarriage resolution and a greater number of care teams involved in the miscarriage diagnosis and management. However, due to the small sample size of this study and baseline differences in the study groups, which were not randomized, we were unable to test for significant differences in our study outcomes. Further study is needed to disentangle the causal relationship between socioeconomic and psychosocial status, utilization of the ED, and the patient miscarriage experience.

Strengths of our study include its mixed-methods approach, which offers a more in-depth understanding of the patient experience of miscarriage stratified by location of care. In addition, we used novel objective metrics with regard to the patient experience, including the quantification of care teams and health system interactions.

Our study has several limitations. First, the single-site design and English language requirement limit our generalizability; larger studies with geographic variability would be valuable to inform the best care for patients with concerning symptoms in early pregnancy. Second, several participants initiated pregnancy-related care outside of the study institution and self-referred to the study site prior to recruitment. Data from outside facilities was not part of the electronic medical record and therefore unavailable for extraction, which may have resulted in underestimates of the time to miscarriage resolution, number of health care interactions, and number of care teams. Third, psychosocial questionnaires were administered after the time of miscarriage diagnosis, which might have impacted our ability to determine the directional relationship between post-traumatic stress disorder scores and ED exposure. However, given that the PCL-C focuses on historical trauma, and that the groups did not differ on our measure of acute stress (PSS), it is likely that this finding related to chronic stress and was not a reaction to the miscarriage or their miscarriage care.

Miscarriage is associated with a negative psychological impact for many people, with clinically important symptoms of depression and anxiety in 22-41% of women in the first week after miscarriage (13), and the emotional experience of miscarriage can persist even after grief and depressive symptoms have resolved (14). Insufficient psychosocial support has been identified as a major gap in miscarriage care (15, 16). Early pregnancy assessment units, which offer expedited evaluation of early pregnancy problems, with on-site ultrasound and health care providers trained in both the clinical and emotional care of miscarriage, may optimize the patient experience (17). However, not all health systems include early pregnancy assessment units, and given that miscarriage treatment can be safely provided in emergency departments (18, 19), this particularly vulnerable population undergoing miscarriage or possible miscarriage may warrant special attention. Previous research has demonstrated that the quality of miscarriage care improves when health care providers offer patients both medical information and emotional validation, and involve them in clinical decision-making (4, 9, 20–22), and caregivers can integrate these behaviors in the emergency room setting. Future studies should investigate whether specific interventions in the provision of miscarriage care, such as minimizing care teams, clarifying communication about diagnosis and treatment, and providing targeted emotional support, improve patients’ experience.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Supported in part by R01 HD071920-01.

The authors thank C. Neill Epperson, MD for her guidance with the psychosocial assessments.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure

Andrea H. Roe, MD, MPH, received money paid to her institution for her role as the site PI for a Sebela Pharmaceuticals trial of an investigational copper IUD (VeraCept). The other authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

Each author has confirmed compliance with the journal’s requirements for authorship.

References

- 1.Rossen LM, Ahrens KA, Branum AM. Trends in Risk of Pregnancy Loss Among US Women, 1990-2011. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2018. January;32(1):19–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang X, Chen C, Wang L, Chen D, Guang W, French J. Conception, early pregnancy loss, and time to clinical pregnancy: a population-based prospective study. Fertil Steril 2003. March;79(3):577–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wittels KA, Pelletier AJ, Brown DF, Camargo CA Jr. United States emergency department visits for vaginal bleeding during early pregnancy, 1993-2003. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2008. May;198(5):523, e1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geller PA, Psaros C, Kornfield SL. Satisfaction with pregnancy loss aftercare: are women getting what they want? Arch Womens Ment Health 2010. April;13(2):111–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farren J, Mitchell-Jones N, Verbakel JY, Timmerman D, Jalmbrant M, Bourne T. The psychological impact of early pregnancy loss. Hum Reprod Update 2018. November 1;24(6):731–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bellhouse C, Temple-Smith M, Watson S, Bilardi J. “The loss was traumatic… some healthcare providers added to that”: Women’s experiences of miscarriage. Women and birth : journal of the Australian College of Midwives 2019. April;32(2):137–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clement EG, Horvath S, McAllister A, Koelper NC, Sammel MD, Schreiber CA. The Language of First-Trimester Nonviable Pregnancy: Patient-Reported Preferences and Clarity. Obstet Gynecol 2019. January;133(1):149–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kangovi S, Barg FK, Carter T, Long JA, Shannon R, Grande D. Understanding why patients of low socioeconomic status prefer hospitals over ambulatory care. Health affairs (Project Hope) 2013. July;32(7):1196–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schreiber CA, Chavez V, Whittaker PG, Ratcliffe SJ, Easley E, Barg FK. Treatment Decisions at the Time of Miscarriage Diagnosis. Obstetrics & Gynecology 2016;128(6):1347–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tang N, Stein J, Hsia RY, Maselli JH, Gonzales R. Trends and characteristics of US emergency department visits, 1997-2007. Jama 2010. August 11;304(6):664–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MacWilliams K, Hughes J, Aston M, Field S, Moffatt FW. Understanding the Experience of Miscarriage in the Emergency Department. Journal of emergency nursing: JEN : official publication of the Emergency Department Nurses Association 2016. November;42(6):504–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baird S, Gagnon MD, deFiebre G, Briglia E, Crowder R, Prine L. Women’s experiences with early pregnancy loss in the emergency room: A qualitative study. Sexual & reproductive healthcare : official journal of the Swedish Association of Midwives 2018. June;16:113–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prettyman RJ, Cordle CJ, Cook GD. A three-month follow-up of psychological morbidity after early miscarriage. The British journal of medical psychology 1993. December;66 ( Pt 4):363–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Volgsten H, Jansson C, Svanberg AS, Darj E, Stavreus-Evers A. Longitudinal study of emotional experiences, grief and depressive symptoms in women and men after miscarriage. Midwifery 2018. September;64:23–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simmons RK, Singh G, Maconochie N, Doyle P, Green J. Experience of miscarriage in the UK: qualitative findings from the National Women’s Health Study. Soc Sci Med 2006. October;63(7):1934–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Punches BE, Johnson KD, Gillespie GL, Acquavita SA, Felblinger DM. A Review of the Management of Loss of Pregnancy in the Emergency Department. Journal of emergency nursing: JEN : official publication of the Emergency Department Nurses Association 2018. March;44(2):146–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsartsara E, Johnson MP. Women’s experience of care at a specialised miscarriage unit: an interpretative phenomenological study. Clinical Effectiveness in Nursing 2002 2002/June/01/;6(2):55–65. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kinariwala M, Quinley KE, Datner EM, Schreiber CA. Manual vacuum aspiration in the emergency department for management of early pregnancy failure. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine 2013;31(1):244–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schreiber CA, Creinin MD, Atrio J, Sonalkar S, Ratcliffe SJ, Barnhart KT. Mifepristone Pretreatment for the Medical Management of Early Pregnancy Loss. N Engl J Med 2018. June 7;378(23):2161–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stratton K, Lloyd L. Hospital-based interventions at and following miscarriage: literature to inform a research-practice initiative. The Australian & New Zealand journal of obstetrics & gynaecology 2008. February;48(1):5–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wallace RR, Goodman S, Freedman LR, Dalton VK, Harris LH. Counseling women with early pregnancy failure: utilizing evidence, preserving preference. Patient education and counseling 2010;81(3):454–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Richardson A, Raine-Fenning N, Deb S, Campbell B, Vedhara K. Anxiety associated with diagnostic uncertainty in early pregnancy. Ultrasound in obstetrics & gynecology : the official journal of the International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology 2017. August;50(2):247–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.