Abstract

Congenital central hypoventilation syndrome (CCHS) represents a rare genetic disorder usually caused by mutations in the homeodomain transcription factor PHOX2B. Some CCHS patients suffer mainly from deficiencies in CO2 and/or O2 respiratory chemoreflex, whereas other patients present with full apnea shortly after birth. Our goal was to identify the neuropathological mechanisms of apneic presentations in CCHS. In the developing murine neuroepithelium, Phox2b is expressed in three discrete progenitor domains across the dorsal-ventral axis, with different domains responsible for producing unique autonomic or visceral motor neurons. Restricting the expression of mutant Phox2b to the ventral visceral motor neuron domain induces marked newborn apnea together with a significant loss of visceral motor neurons, RTN ablation, and preBötzinger complex dysfunction. This finding suggests that the observed apnea develops through non-cell autonomous developmental mechanisms. Mutant Phox2b expression in dorsal rhombencephalic neurons did not generate significant respiratory dysfunction, but did result in subtle metabolic thermoregulatory deficiencies. We confirm the expression of a novel murine Phox2b splice variant which shares exons 1 and 2 with the more widely studied Phox2b splice variant, but which differs in exon 3 where most CCHS mutations occur. We also show that mutant Phox2b expression in the visceral motor neuron progenitor domain increases cell proliferation at the expense of visceral motor neuron development. We propose that visceral motor neurons may function as organizers of brainstem respiratory neuron development, and that disruptions in their development result in secondary/non-cell autonomous maldevelopment of key brainstem respiratory neurons.

Keywords: apnea, chemosensation, congenital central hypoventilation syndrome (CCHS), Nkx2.2, PHOX2B, respiratory rhythm-generating networks

INTRODUCTION

Although ventilation is a necessary biological function beginning at birth and ending at death, the pathophysiological mechanisms by which Central Nervous System (CNS) ventilation control dysfunction develops in newborns continues to elude neuropathologists. Significant insights into CNS ventilatory control have come from studying human diseases such as Congenital Central Hypoventilation Syndrome (CCHS). CCHS (OMIM #209880) represents a rare human genetic disorder of the Autonomic Nervous System (ANS) caused by heterozygous mutations in PHOX2B (1, 66). CCHS patients show monotonous breathing rhythms that do not change in response to altered levels of CO2 or O2, especially during non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep (29, 67). CCHS patients present with a spectrum of CNS respiratory control pathophysiologies, ranging from deficiency in chemosensation during unassisted breathing, to the most severe manifestations of overt apnea in the neonatal setting that requires life-sustaining mechanical ventilation regardless of vigilance states. Neonatal apnea may present in CCHS patients regardless of PHOX2B mutation type, and the developmental mechanisms by which neonatal apneic phenotypes manifest in some CCHS patients but not in others is not well understood.

Breathing maintains homeostatic pH and arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide (pCO2) and partial pressure of oxygen (pO2). This is achieved by a complex interaction of multiple rhombencephalon-derived neural circuits. Central chemoreceptors, which are capable of monitoring and sensing blood pH and CO2 levels as well as modulating the respiratory rhythm, stimulate respiration in response to hypercapnia (22). Excitatory neurons of the retrotrapezoid nucleus (RTN), derived embryonically from the dorsal dB2 rhombencephalic progenitor domain, mediate central chemoreception (51). Murine RTN neurons, which are situated ventral to the Facial Motor Nucleus (nVII) on the lateral medullary surface, express Vglut2, Phox2b, galanin and neuromedin B, among other markers (55). During acidification (which parallels an increase in arterial pCO2), RTN neurons send signals to the ventral respiratory column to regulate ventilation. Neuropathological findings in rodent CCHS models demonstrating RTN dysgenesis support the notion that the deficient chemoreflex of CCHS patients may result from defects in RTN function (13). However, RTN neuronal loss does not itself induce full apneic phenotypes in mice (41) which suggests that the neuropathological mechanisms by which patients develop neonatal apnea distinct from the mechanisms which induce defective chemosensation.

Data from human patients and murine CCHS models lead to an obvious question. Namely, does CCHS pathophysiology result from dysfunctional Phox2b-targetted gene expression in known Phox2b-positive respiratory centers (such as the RTN), or does CCHS disease result from developmental pathologies in non-respiratory progenitor cells? Given that Phox2b expression occurs across a wide swath of cells during embryogenesis, we proceeded to express a highly penetrant NPARM Phox2b mutation in two progenitor lineages that do not give rise to the RTN. We found that targeting mutant Phox2b into the visceral motor neuron progenitor domain, achieved by breeding Nkx2.2Cre mice to Phox2bΔ8 mice, resulted in a significant population of pups showing apnea shortly after birth with electrophysiological abnormalities in the PreBotzinger complex, as well as deficiencies in a spectrum of rhombomeric nuclei not developmentally derived from Nkx2.2-expressing progenitors. We provide evidence for a non-cell autonomous mechanism to CCHS neuropathology.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental animals and animal husbandry procedures

Procedures utilizing mice were performed in accordance with The Ohio State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines (protocol number: 2012A00000162-R1) and in accordance with the University of Chicago Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines (protocol number: 72486). Information regarding the strains of mice used including strain number and geno-typing details are delineated in Supporting Table S1. In this developmental screen, Phox2b+/Δ8-expressing mice were compared to their Phox2b+/+ littermates. Nkx2.2Cre (kind gift of Dr. Michel Matis, Rutgers University (63)) and Olig3Cre (kind gift of Dr. Yasushi Nakagawa, University of Minnesota (62)) mice were bred with a ROSATdTomato transgenic reporter line (Ai14) (36) to determine which structures are developmentally dependent on Nkx2.2 or Olig3 expression, respectively. Cre-inducible inhibitory Designer Receptors Exclusively Activated by Designer Drugs (DREADD) (ROSA+lhM4Di) (68) mice were bred with Nkx2.2Cre and Vglut2Cre (61) drivers in order to selectively silence with clozapine-N-oxide (CNO) (# C0832, Sigma-Aldrich) treatment neurons expressing the inhibitory, hM4Di DREADD receptor. An intersectional genetic strategy in which the Intersectional RC::FLTG mouse line (46) was bred with the Nkx2.2Cre and Phox2b-FLPo (26) Fsuppmouse lines in order to evaluate Nkx2.2 and Phox2b embryonic derivation. Genotyping was verified by PCR (Terra PCR Direct Red Dye Premix #639286, Clontech Laboratories) using primers detailed in Table S1.

Histology, immunohistochemistry and microscopy

Histology and immunostaining

Mice were anesthetized using a mixture of ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg) in sterile saline and perfused transcardially, first with 10 mL of PBS, then with 5 mL of 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS. Pup brains were drop-fixed in 4% PFA in DEPC-PBS at 4°C overnight, equilibrated in 30% sucrose/DEPC-PBS at 4°C until tissue sank to bottom of container and OCT embedded. OCT-embedded pup brains were cryosectioned at thicknesses optimized for each antibody. For immunostaining, sections exceeding 25 μm were processed as floating sections in a 96-well plate. Brain tissue was antigen retrieved with 10mM citrate buffer (pH 6.0) in an 80° C water bath for 30 minutes then washed with PBS + 0.1% Triton X-100 (#02300221, MP Biomedicals) three times for 10 minutes. Tissue was then blocked with 10% horse serum (#06750, Stem Cell Technologies) and 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS before incubation with primary antibody solution (5% horse serum, 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS) overnight at 4°C. Tissue was washed with PBS + 0.1% Triton X-100 three times for ten minutes before incubation with secondary antibody solution (5% horse serum, 0.1% Triton X-100) and counterstained with DAPI 1:1000 (#D1306, Invitrogen) for two hours at room temperature in the dark. Sections were first washed with PBS two times then with dH2O once for 10 minutes and coverslips were mounted with ProLong Gold Antifade Mountant (#P36934, Invitrogen). Our standard operating procedures for embryo analyses were similar, but with some modifications delineated in the Supporting Information.

Analyses of the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) in Olig3Cre, Phox2bΔ8 and control littermate P0 pups were challenging due to different atlases using varied terminology. The terms commissural NTS, lateral NTS, and medial NTS are utilized as shown in the Allen Developing Brain Atlas. The term rostral NTS, which is not present in the Allen Brain Atlas, is denoted to represent a population of NTS cells described by Paul Gray that are LMX1B-derived (21). Using the Allen Developing Brain Atlas for orientation, sister sections of the hindbrain, cryosectioned at 40 μm, were stained for PHOX2B and Choline Acetyltransferase (ChAT). Dorsal hindbrain structures analyzed, using Neurolucida’s cell counter program, were PHOX2B+, ChAT− including the NTS and the area postrema (AP). All antibody details are delineated in Table S2.

Microscopy and image analysis

Fluorescent images were captured on a Carl Zeiss Axio Imager Z.1 with LSM700 confocal microscope with a motorized stage using 10x/0.3 NA, 20X, and 40x/1.3 NA Oil DIC objectives. For cell cycle analyses and visualization of hindbrain pathology in Phox2bΔ8-expressing mice, single optical slices or Z-stacks were taken at 20X or 40x magnification. Tiled images were tiled with 10% overlap and stitched by Zen software (2011, Black, v. 7,0,0,285) into a 3D image. Cell quantitation was performed using different techniques optimized for each experiments as follows: (i) for the Olig3cre experiments were carried out in Neurolucida software (v 11.11.2, MicroBrightField) using the cell detector capable of automatic cells counts within a user-specified region, (ii) for quantitation of P0/1 Nkx2.2cre, Phox2bD8 neuropathology and BrdU quantitation, we the manual cell counter system from FIJI, (iii) for quantitation of E12.5 emrbyos and Phox2b nuclei segmentation of E10.5 embryos, we implemented custom R scripts through “imager” or “EBImage” packages. Details are delineated in the Supporting Information. For RNA quantitation of Phox2b-202 FISH, the entire thickness of analyzed cells was included in analysis by capturing 25 Z sections with a step size of 0.3μm. Images were converted into a single Z-plane by maximum intensity projection in FIJI (v1.0, RRID: SCR_002285) and Phox2b-202 puncta manually counted in FIJI using the cell counter plugin.

Cell cycle analysis

For cell cycle length analyses, an E10.5 pregnant dam carrying Nkx2.2Cre, Phox2bΔ8 embryos were injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with 5-Chloro-2′-deoxyuridine thymidine (CldU) at 50 mg/kg (#C6891, Sigma-Aldrich). The dam was then injected i.p. with 5-Ethynyl-2’-deoxyuridine (EdU) at 50 mg/kg (#E10187, Thermo Fisher Scientific) 2 hours after CldU administration. Thirty minutes after EdU injection, E10.5 embryos were collected via cesarean section. Cryosections were taken at 14 μm, unmasked via antigen retrieval with sodium citrate 10mM, and stained with pertinent antibodies. Note that CldU was immunolabeled with anti-BrdU antibody (Novus Biologicals, #NB500-169), and therefore all figure legends are referred to as BrdU represent CldU signals. EdU labeling was achieved using an Alexa Fluor™ 488 Click-iT Kit (#C10337, Thermo Fisher Scientific) as specified in the manufacturer’s protocol. Control mice were littermates of Nkx2.2Cre, Phox2bΔ8 mice that do not express mutant Phox2bΔ8 (ie, they are Phox2b+/+). Detailed workflows of the image analysis workflows are available in the Supporting Information.

Gene expression analysis

RT-qPCR: Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) was carried out using the SuperScript™ III First-Strand Synthesis (#18080051, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and SYBR™ Green PCR Master Mix (#4309155, Thermo Fisher Scientific) for a two-step RT-qPCR assay on a Step One Plus RT-PCR system (# 4376600, Applied Biosystems). Step One v2.3 software (Applied Biosystems) was used for comparative Ct analysis, with mouse Gapdh as the endogenous control. Primers for RT-qPCR are delineated in the Supporting Information.

RNA fluorescence in situ hybridization

To selectively target the mRNA of either Phox2b splice variant 1 (Phox2b-201) or the putative Phox2b alternative splice variant 2 (Phox2b-202), we utilized the Stellaris Probe Designer (http://www.biosearchtech.com/stellaris-designer) to create two custom sets of fluorescently labeled oligonucleotides. The first set, Phox2b-201, consisted of 34 oligos mapped to the 3’UTR and C-terminal end of Phox2b exon 3 splice variant 1 and labeled with CAL Fluor 610. These oligos were designed against the mouse Phox2b exon 3, and because Phox2bΔ8 mutant mice express human PHOX2B exon 3 instead of mouse Phox2b exon 3, Phox2b-201 oligos do not hybridize to Phox2bΔ8 transcripts. The second set, Phox2b-202, was comprised of 21 oligos mapped to the 3’UTR and C-terminal end of Phox2b exon 2 splice variant 2 and labeled with Quasar 670. For quality control, ShipReady Stellaris FISH probes against Gapdh fluorescently labeled with Quasar 570 dye (#SMF-3002-1, LGC Biosciences) were used. Sequences of oligos included in each custom probe sets are listed in Table S3. RNA FISH hybridizations were performed overnight according to the manufacturer’s protocol for frozen mouse brain tissue.

Physiological testing

Newborn respiration analysis in mutant Phox2bΔ8 mice

Respiration was analyzed in neonatal pups from both Nkx2.2Cre, Phox2bΔ8 and Olig3Cre, Phox2bΔ8 genotypes using a mouse pup plethysmography chamber (#987365, DSI) and QT preamplifier (#894002, DSI). P0 pups were placed in the chamber in the head-out configuration and acclimated for 1 minute before respiration was recorded for 10 minutes. Breathing in adult mice was monitored using a whole-body plethysmographer (#992541, DSI) with the Buxco Finepointe 2-site controller (#993582, DSI). Finepoint software was used (v2.4.7.10175) to record respiration parameters including, but not limited to, respiratory frequency (fR, breaths per minute), tidal volume (VT, mL/kg) and minute ventilation (VE, mL/min/kg). Quantitation of the number and duration of apneic occurrences was done manually by a blind observer. Apnea was defined as the absence of plethysmographic flow signal for more than two expected respiratory cycles (15, 27). Justification for pooling control genotypes is presented in the Supporting Information.

Chemogenetic experiments (newborn pups)

hM4Di expressing P1 pups underwent their first recording at baseline for 10 minutes. Following the initial recording, pups underwent CNO administration by intraperitoneal injection (i.p.) followed by 60 minutes at room air to equilibrate. Pups were then placed in the plethysmographer and respiration recorded for another 10 minutes. Control mice were littermates of ROSA+/hM4Di mice that do not express Cre-recombinase.

Chemogenetic experiments (adult mice): respiration analysis following neuronal circuit inhibition in ROSA+/hM4Di adult mice

hM4Di expressing adult mice underwent acclimatization to the plethysmographer for 15 minutes/day for 3 days. Plethysmograph recordings lasting 10 minutes prior to CNO administration via intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection (0.25 mg/kg) represented our baseline values. After 60 minutes, respiration was recorded and analyzed during a 10-minute recording interval. Data processing and analysis are detailed in the Supporting Information.

Electrophysiological slice recordings

Brainstem slices containing the preBötC were prepared from Nkx2.2Cre, Phox2bΔ8 and control mice (postnatal Day 0) as described previously (18). Briefly, the dorsal face of the isolated brainstem was glued to an agar block and submerged in artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF, ~4°C) equilibrated with Carbogen (95% O2, 5% CO2). Transverse slices were made through the brainstem until anatomical landmarks, such as the inferior olive and hypoglosssal nucleus (XIIn), were identified. A single slice (600 ± 30 μm) containing the preBötC and XIIn was taken.

The composition of aCSF was as follows (in mM): 118 NaCl, 3.0 KCl, 25 NaHCO3, 1 NaH2PO4, 1.0 MgCl2, 1.5 CaCl2 and 30 d-glucose. When equilibrated with Carbogen at ambient pressure, the aCSF had a pH of 7.40-7.45 and an osmolarity of 308 ± 4 mOSM. Before recording, the extracellular KCl concentration was raised to 8.0 mM to induce rhythmic activity from the preBötC. Extracellular population activity was recorded with a glass suction pipette (tip resistance < 1 MΩ) filled with aCSF that was positioned over the ventral respiratory column containing the preBötC. Recorded signals were amplified 10 000X, filtered (low pass, 1.5 kHz; high pass, 250 Hz), rectified, and integrated using an electronic filter. Recordings were acquired in pCLAMP software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) and were analyzed post hoc in Clampfit software (version 10.2). Calculation of Irregularity score for a given metric was performed post hoc and previously described by (17).

Statistical modeling and data analysis

Descriptive and inferential statistics were performed in Microsoft Excel or R Studio. Student’s t-test for pairwise comparison or ANOVA with Tukey’s HSD correction for multiple comparisons was used as appropriate for each experiment as indicated in figure legends. Final figures were prepared using Adobe Illustrator © 2019 v24. Detailed data analytical pipelines are presented in the Supporting Information.

RESULTS

Selective expression of NPARM Phox2b in Nkx2.2-derived cells results in an apneic presentation at birth

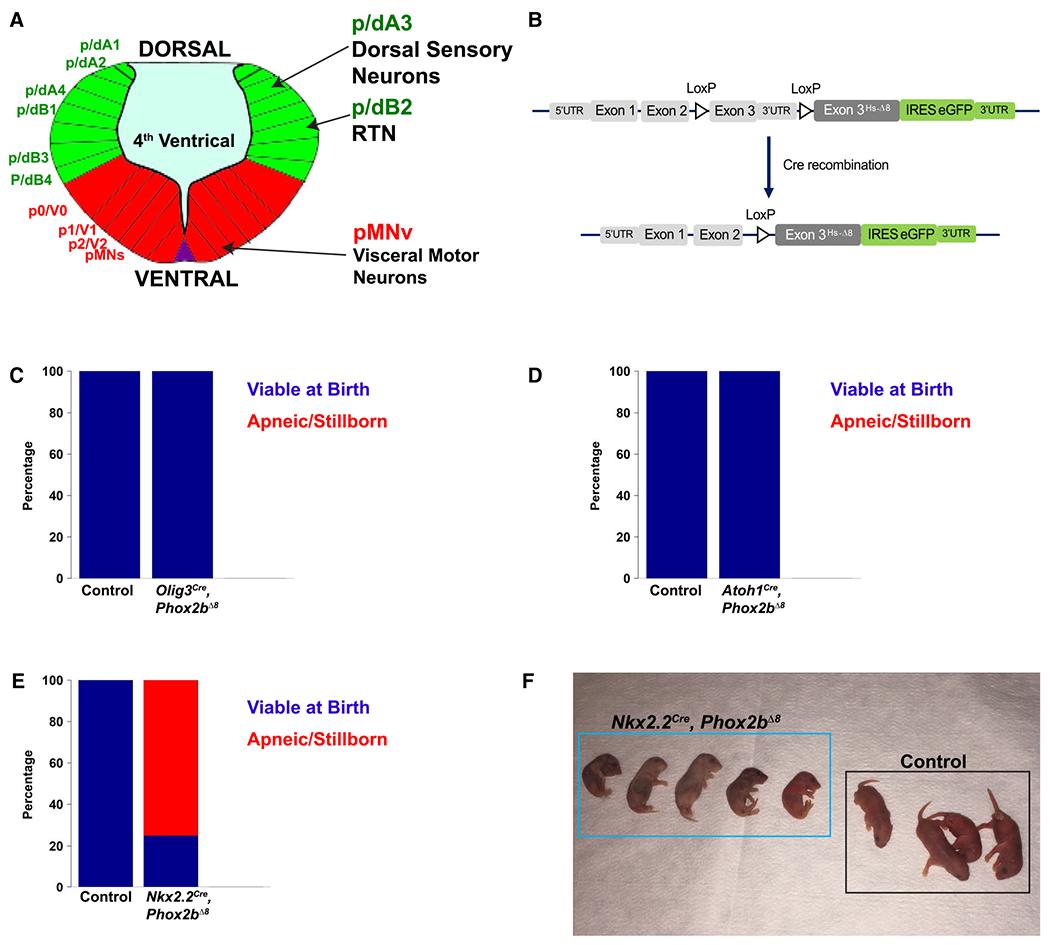

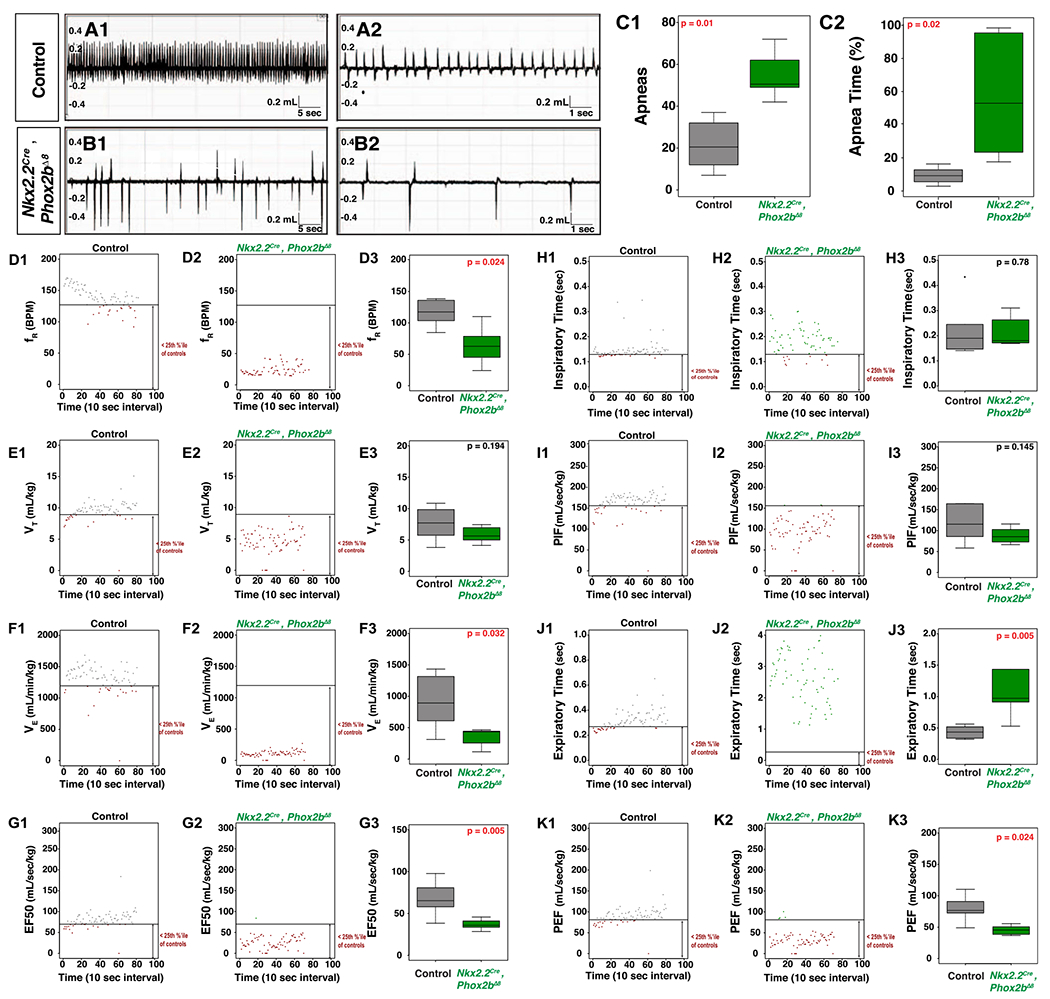

We utilized a spectrum of Cre drivers that develop into key breathing structures (see schematic in Figure 1A,B: Atoh1Cre, Olig3Cre and Nkx2.2Cre induce recombination in cells giving rise to the CO2-sensitive neurons of the RTN (50, 51, 64), dorsal rhombencephalic sensory neurons (58), and rhombencephalic ventral visceral motor neuron progenitor domain (pMNv) (7, 69), respectively. The results of these crossings are shown in Figure 1C–E, which demonstrates that Phox2bΔ8 expression in Nkx2.2-derived cells results in neonatal apneic presentations in mice (Figure 1F) (P = 0.0005 by Fisher’s Exact Test). As pathological and functional evaluation of mutant Phox2b expression in Atoh1Cre-expressing cells (37) has been extensively evaluated in the scientific literature (12–14, 24, 48), we, therefore, focused our investigations on expressing Phox2bΔ8 in progenitor populations derived from the ventral (Nkx2.2-derived) and dorsal (Olig3-derived) poles as their respective contributions to autonomic nervous system development and function have been less explored. For breathing pattern, we subjected newborn Nkx2.2cre, Phox2bΔ8 pups to restrained (head out) plethysmography (Figure 2). An example of the respiratory pattern in control and mutant animals is shown at two different timescales in Figure 2A,B; note that the Nkx2.2cre, Phox2bΔ8 animals show irregular patters with frequent and longer apneas (Figure 2C). Frequency (fR) and minute ventilation (VE) were significantly diminished in Nkx2.2cre, Phox2bΔ8 animals (Figure 2D,F). We also noted significant neurophysiological findings during expiration, including increased expiratory time (Te) (Figure 2J), with decreased EF50 (Figure 2G) and peak expiratory flow (PEF) (Figure 2K). However, tidal volume (VT) (Figure 2E), mean inspiratory time (Ti) (Figure 2H) and peak inspiratory time (PIF) (Figure 2I) were not different between groups. In view of these findings, we performed linear regression analysis of these data by placing the frequency (fR) as the response variable with both expiratory time (Te) and inspiratory time (Ti) as the predictor variables. The linear regression data are reported in Table S4. We note that the Nkx2.2Cre, Phox2bΔ8 animals showed a significantly repressed linear relationship between fR and Te. Specifically, the model predicts that each unit increase of Te reduces fR by 109 breaths per min (BPM) in the controls, whereas in the Nkx2.2cre, Phox2bA8 animals each unit increase in Te reduces fR by only 35 BPM. Of note, the Ti did not show a significant linear relationship with fR in the Nkx2.2cre, Phox2bΔ8 animals, indicating that in these mutants fR could not be predicted by Ti, yet showed no change in mean Ti between mutant and control groups (Figures 2H1 and 3). We conclude that expressing Phox2bΔ8 in the Nkx2.2 lineage induces an apneic phenotype at birth as well as an abnormal respiratory pattern.

Figure 1. Experimental design and mouse developmental screen.

A. Artistic rendering of rhombomere 4 of an E10.5 mouse embryo. The developing rhombencephalon can be subdivided into dorsal progenitor domains (green) and ventral domains (red). Within each domain, specific neuronal and glial populations are generated. Phox2b is expressed in 3 progenitor domains depicted on the right: dA3, dB2, and pMNv. These progenitor domains give rise to dorsal sensory neurons, retrotrapezoid nucleus RTN, and visceral motor neurons, respectively. B. Transgenic mouse strategy. The humanized NPARM Phox2b mouse mutation is located in exon 3. Cre-mediated recombination replace the endogenous murine exon 3 with a human exon3 harboring an eight-nucleotide deletion (Hs-Δ8). C-E. Developmental screen of mice to identify apneic/stillborn presentations. Stacked bar graphs show proportion of pups viable at birth in blue, with apneic/stillborn pups in red. Genotype is denoted on the bottom of each bar graph. This screen (C) derives from 28 control pups and 44 mutant pups spread over 10 litters, (D) derives from 10 control pups and 18 mutant pups spread over six litters, (E) derives from 10 control pups and 12 mutant pups. (F) Photograph of a representative Nkx2.2Cre, Phox2bΔ8 litter showing absent or limited respiratory movements and cyanosis at birth.

Figure 2. Respiratory Physiology in newborn Nkx2.2cre, Phox2bΔ8 pups.

A and B. Wave forms obtained from head out plethysmography configuration. Genotype designated on left. A1 and B1 are 1-minute-long traces demonstrating the marked differences in respiratory frequency between control and Nkx2.2Cre, Phox2bΔ8 mice. A2 and B2 are 16-second-long breathing traces demonstrated the waveforms of each breath for control and Nkx2.2Cre, Phox2bΔ8 mice. C1 and C2 show the number and duration of apneas, respectively. Analysis of respiratory patterns is shown as follows: D1-D3 show frequency (fR), E1-E3 show tidal volume (VT), F1-F3 show minute ventilation (VE), G1-G3 show EF50, H1-H3 show inspiratory time (Ti), I1-I3 show peak inspiratory flow (PIF), J1-J3 show Expiratory time (Te), and K1-K3 show peak expiratory flow. In each series, an example animal is plotted for each genotype. Each plot shows a line that represents the 25th percentile of pooled control data, with each data point lying out of the 25th percentile colored in red (note the significant number of red data points in the mutants). Box-whisker plots show the median as the bar, the box is the interquartile range, and the whiskers are 1.5 times the interquartile range. Control is in gray, Nkx2.2Cre, Phox2bΔ8 is green. Corrected P-values are shown in the top right of each boxplot, with red indicating tests with statistical significance. Nkx2.2Cre, Phox2bΔ8 show significantly decreased frequency, minute ventilation, EF50, peak expiratory time and an increased expiratory time. n = 6 control, n = 6 Nkx2.2cre, Phox2bΔ8 mice obtained from two distinct litters for these analyses.

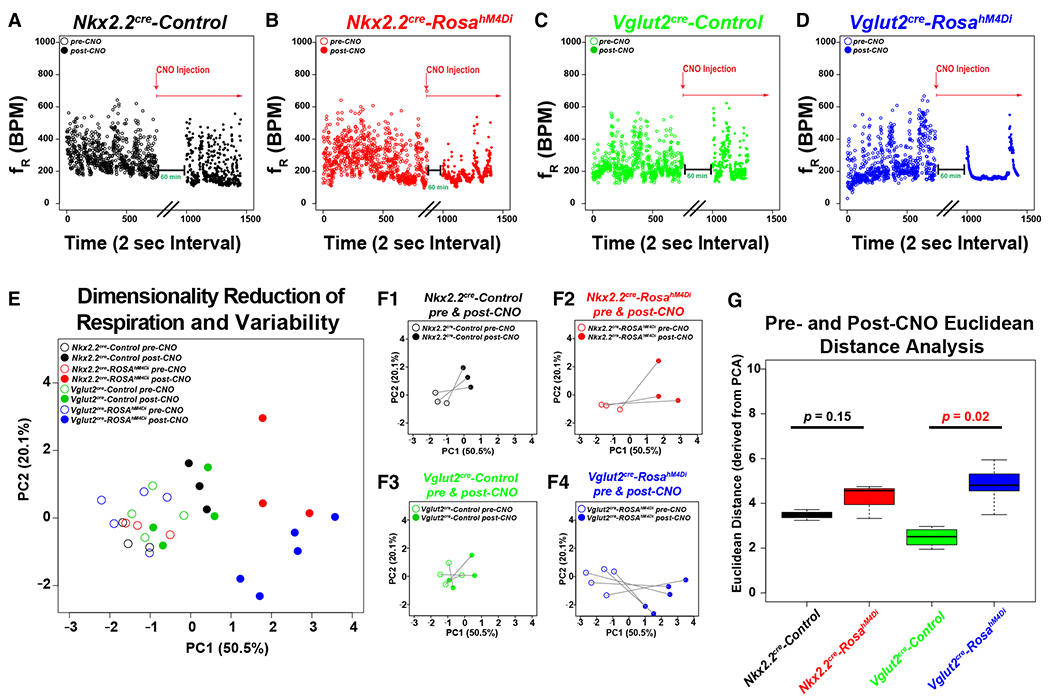

Figure 3. Respiratory Physiology of Nkx2.2Cre hM4Di inhibitory DREADD mice.

A-D. Dot plots show genotype on top, frequency on Y-axis (breaths per minute), and time (2 sec bins) on X-axis for sample animals before (open circle) and after (closed circle) i.p. injection of CNO (0.25 mg/kg). In each dot plot, the experimental paradigm is shown delineating the CNO treatment. Note that data were appended from pre and post-CNO recordings and plotted continuously on the same graph for ease of representation (black parallel lines on X-axis denote breaking of the continuous scale, with the post-CNO recording arbitrarily beginning at x = 1000). Nkx2.2Cre, ROSA+/h4MDI animals are plotted in red for dot plots, PCA, and bar graphs, Nkx2.2Cre, Controls are plotted in black, Vglut2Cre, are plotted in green, and Vglut2Cre, ROSA+/h4MDI animals are plotted in blue. E. Principal component analysis of all of the ventilation data and respiration variability data derived from Poincaré analysis are graphed along PC1 (50.5% of variance) and PC2 (20.1% of variance). Color coded legend is in the top right for E-F. F. For ease of representation, each group is graphed in isolation before and after CNO treatment along PC1 and PC2. F1 = Nkx2.2cre Control, F2 = Nkx2.2cre, ROSAh4MDi, F3 = Vglut2cre control, F4 = Vglut2cre, Rosah4MDi. G. The Euclidean distance along all of the principal components was calculated for each animal before and after CNO treatment, and then graphed as a box-whisker plot based on genotype. Box plots show solid black line to represent the median, the box represents in the interquartile range, and the whiskers represent 1.5 times the interquartile range. P-values of no significance are shown in the box plots in black font, with corrected P-values of < 0.05 shown in red. For Nkx2.2 experiments, Nkx2.2Cre, ROSA+/h4MDI n = 3, control animals n = 3. For Vglut2 experiments, Vglut2Cre, ROSA+/h4MDI n = 4, control n = 5.

Unlike the Nkx2.2cre, Phox2bΔ8 animals, which show perinatal lethality, the viability of Olig3cre, Phox2bΔ8 animals permitted us to test the autonomic responses to a wide array of physiological challenges across the lifespan. These data are illustrated in Figures S2 and S3. Olig3cre, Phox2bΔ8 animals do not show changes in respiratory parameters during the postnatal period relative to controls. P21 and adult animals showed no significant difference from controls during hypercapnia and hypoxic challenges (Figures S2), nor were changes noted during hyperoxic hypercapnia (Figure S3). We conclude that Phox2bΔ8 expression in Olig3-derived cells does not alter the hypercapnic nor hypoxic respiratory chemoreflex.

Chemogenetic silencing of Nkx2.2-derived neurons does not induce apnea

Having established that Phox2bΔ8 expression in progenitors derived front Nkx2.2- (but not Olig3-derived) leads to neonatal respiratory dysfunction, we next asked if modulating Nkx2.2-derived cells through chemogenetic-mediated silencing would result in apneic phenotypes similar to Phox2bΔ8 expression. We utilized recombination with the Vglut2Cre transgenic mouse as an expected positive control since VGLUT2 shows RTN expression (2, 39) and is expressed in ~45% of DBX-1-derived preBötC neurons (3, 16). To achieve this, we interbred Nkx2.2Cre or Vglut2Cre mice with ROSA+/hM4DI, a Cre-inducible inhibitory DREADD mouse line (ROSA+/hM4Di). In ROSA+/hM4Di mice, neurons derived from Cre-positive cells express the hM4Di DREADD receptor. Cells harboring the hM4Di DREADD receptor become hyperpolarized after treatment with the ligand clozapine-N-oxide (CNO). For both the Nkx2.2Cre and Vglut2Cre mouse experiments, we performed baseline plethysmography measurements of littermate control ROSA+/hM4Di mice before and 1-hour post-i.p. CNO administration, and compared the results to Cre-positive, ROSA+/hM4Di mice. Results from our assays are illustrated in Figures 3 and S4–S6 (Online Resource 1). Note that in Vglut2Cre experiments performed on adult mice, application of CNO to Cre-positive ROSA+/hM4Di mice significantly decreased the variability of breaths per minute (Figure 3A–D), which we attribute to CNO-dependent changes in CNS ventilation control. These experiments resulted in a high dimenstionality dataset. We were successful in reducing dimensions of our data by implementing principal component analysis on the respiratory and respiratory variability data. Specifically, our initial dataset of 48 data dimension per animal were reduced to 30 principal components (PC, see details in Supporting Information). Figure 3E–F shows coordinates along PC1 and PC2 pre-CNO (open circles) and post-CNO (closed circles). This analysis permitted us to calculate the Euclidean distance for each animal pre-CNO and post-CNO across the 30 PC dimensions, a measure representing the total CNO effect on each animal relative to the total variance noted in the dataset amongst all genotypes. As can be seen in Figure 3G, although Nkx2.2cre, ROSA+/hM4Di animals showed a trend to increased Euclidean distance, it did not meet our threshold of significance. In contrast the significantly different Euclidean distance was noted in the Vglut2cre, ROSA+/hM4Di animals. We also evaluated each parameter head to head using traditional approaches (Figures S4–S6). The following parameters showed no change in mean between pre-CNO and post-CNO administration in the Cre-positive ROSA+/hM4Di mice versus control mice in both the Nkx2.2Cre and Vglut2Cre experiments: frequency (fR, BPM), tidal volume (VT, mL/kg), minute ventilation (VE, mL/min/kg), inspiratory time (Ti, s), expiratory time (Te, s), peak inspiratory flow (PIF, mL/s/kg), peak expiratory flow (PEF, mL/s/kg), expiratory flow at 50% expired volume (EF50, mL/s/kg), end expiratory pause (EEP, ms), and end inspiratory pause (EIP, ms). In summary, chemogenetic silencing of glutamatergic neurons decreases variances of respiratory pattern. We further conclude that silencing Nkx2.2-derived cells does not phenocopy the Nkx2.2Cre, Phox2bΔ8 phenotype.

Nkx2.2 encodes a transcription factor that regulates development of visceral motor neurons, serotonergic neurons, and glia (44). It has been proposed by some authors that serotonergic neurons play a role in rhythmogenesis early in development, which gradually shifts to a chemosensory role in adult mice (6). To test potential effects of serotonergic cell fate, we generated Nkx2.2Cre, ROSA+/hM4Di newborn animals and silenced Nkx2.2Cre derived neurons with CNO and tested respiratory function by head out/restrained plethysmography (Figure S7). Similar to the adult data, we found no change in frequency, tidal volume, minute ventilation, Ti, nor EF50 in Nkx2.2Cre, ROSA+/hM4Di newborn pups. We conclude that chemogenetic silencing Nkx2.2-derived circuits does not decrease respiratory frequency in adults nor in newborn pups.

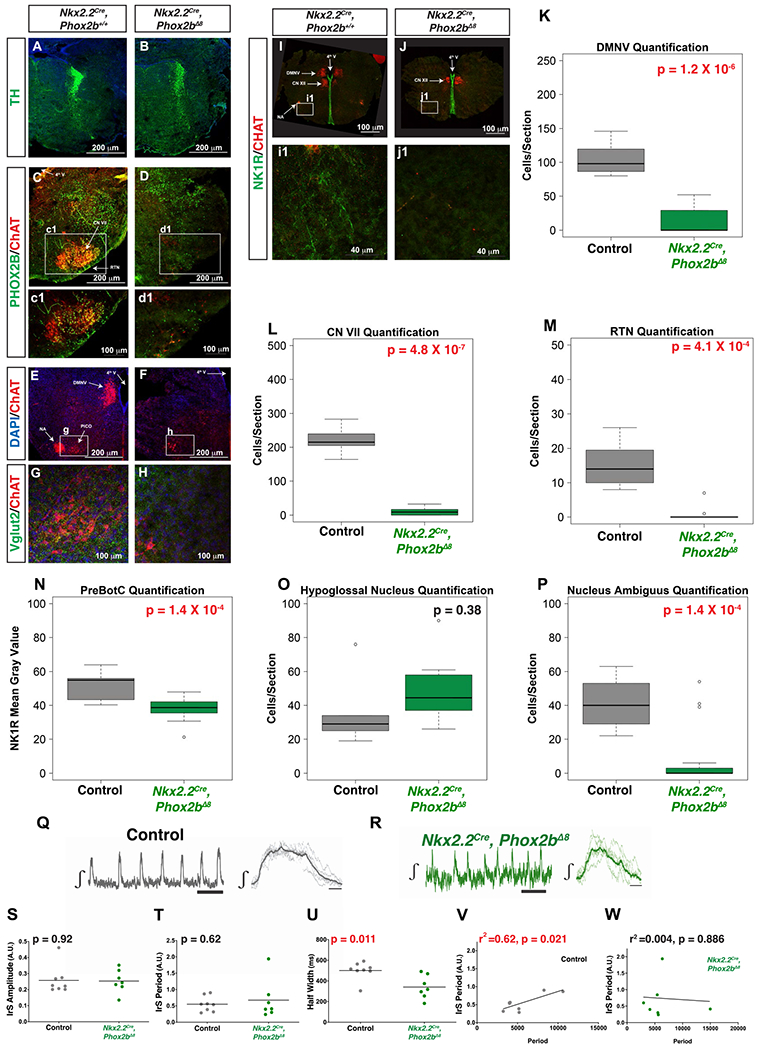

Nkx2.2Cre, Phox2bΔ8 mice show diffuse brainstem neuropathology and weakened inspiratory drive from the preBötC, whereas Olig3cre, Phox2bΔ8 mice show normal dorsal Phox2b-neuron specification

In order to fully understand Nkx2.2Cre, Phox2bΔ8 neuropathology, we generated timed pregnant females and evaluated E18.5 mouse brains. We focused our evaluation on the morphology of well-documented respiratory centers or Phox2b-derived nuclei, including locus coeruleus (LC), dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus nerve (DMNV), cranial nerve VII nucleus (nVII), retrotrapezoid nucleus (RTN), nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS), nucleus ambiguus (NA) and PreBötC. These structures are identified by a combination of immunohistochemical markers within a neuroanatomical context and are illustrated in Figure 4. We note that in contrast to HprtCre, Phox2bΔ8 mice which show loss of LC (Nobuta et al., 2015), Nkx2.2Cre, Phox2bΔ8 mice generate a well-formed LC (Figure 4A,B). The following brainstem nuclei were anatomically unaffected: the NTS, the median raphe (MR), and the PHOX2B-positive cells located in the parvicellular reticular nucleus and vestibular nucleus (data not shown). In contrast, we found a near ablation of the following structures: CN VII (Figure 4C,D), RTN (Figure 4C,D), DMNV (Figure 4I–J) and the NA (Figure 4E,F). We also noted a decreased NK1R mean gray value in the PreBötC region (Figure 4I1–J1,N). We also noted a decrease in Choline Acetyltransferase (ChAT)-positive cells in the area of the post-inspiratory complex (PiCo, Figure 4E–H). To quantitate the differences observed, we counted the number of ChAT-positive cells of the DMNV (Figure 4K), CN VII (Figure 4L, Hypoglossal Nucleus (Figure 4O) and NA (Figure 4P). In addition, we quantified the number of PHOX2B positive cells in the RTN (Figure 4M). These data indicate the Phox2bΔ8expression in Nkx2.2-derived cells leads to widespread cytoarchitectural changes in key respiratory control centers.

Figure 4. Brainstem Neuropathologies of Nkx2.2Cre; Phox2bΔ8 mice are accompanied by weakened inspiratory drive from the preBötC.

A and B. No apparent defect in the Locus coeruleus (TH+) in Nkx2.2Cre, Phox2bΔ8 mice compared to controls noted. C and D. VII nucleus (ChAT in red) and RTN with PHOX2B-positive neurons (green) at the ventral medullary surface. E-H. Significant dysgenesis of dorsal motor nucleus of vagus nerve and nucleus ambiguus at the level of the post-inspiratory complex (PiCo) respiratory oscillator (PICO is delineated in higher magnification in panels g and h for control and mutant mice, respectively). Panels I-J Dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus nerve, nucleus ambiguus and a decreased intensity of NK1R-immunoreactive cells noted. K-P. Box plots show solid black line to represent the median, the box represents in the interquartile range, and the whiskers represent 1.5 times the interquartile range. P-values of no significance are shown in the box plots in black font, with corrected P-values of < 0.05 shown in red. In box plots the parameter tested is labeled on Y-axis corresponding to either the number of ChAT-positive cells/section (K, L, O, P), PHOX2B positive cells/section (M), or NK1R Mean gray Value (N). Genotypes are delineated on X-axis. TH = Tyrosine Hydroxylase, ChAT = Choline Acetyltransferase, NK1R = Neurokinin 1 Receptor, VGLUT2 = vesicular glutamate transporter-2. Nkx2.2Cre, Phox2bΔ8 n = 10 images obtained from three pups, control n = 5 images obtained from two pups. Q-W. Representative image of the integrated inspiratory rhythm from isolated preBötC left, and the mean inspiratory burst (thick gray trace) of seven individual inspiratory bursts (thin gray traces) right, from a control preBötC isolated in a brainstem slice (Q); representative image of the integrated inspiratory rhythm from isolated preBötC left, and the mean inspiratory burst (thick green trace) of seven individual inspiratory bursts (thin green traces) right from a preBötC isolated in a brainstem slice from a Nkx2.2Cre, Phox2bΔ8 animal (R). While no differences were observed when comparing the irregularity score (IrS) of amplitude (S, P = 0.92) and period (T, P = 0.62) between the preBötC from control (n = 8) and Nkx2.2Cre, Phox2bΔ8 (n = 7) animals, halfwidth of preBötC burst from Nkx2.2Cre, Phox2bΔ8 animals has a significant shorter duration (U, P = 0.011). No difference in the mean IrS of period observed. Variance in IrS period was different between the two groups (F = 6.538, P-value for F test to compare variance = 0.026). Positive relationship existed between IrS of period and period in the control group (r2 = 0.62, P = 0.021) (V). In the Nkx2.2Cre, Phox2bΔ8 group, the relationship was flat (r2 = 0.004, P = 0.886) (W).

To address the possibility that the Phox2bΔ8 mutation destabilizes inspiratory drive, we conducted extracellular recordings from the preBötC isolated in brain slices prepared from control (Figure 4Q) and Nkx2.2cre, Phox2bΔ8 (Figure 4R) animals. While the regularity of amplitude (Figure 4S) and period (Figure 4T) was similar between groups, the burst duration was smaller in inspiratory rhythms from Nkx2.2Cre, Phox2bΔ8 animals (Figure 4U). Examining the relationship between irregularity of rhythmogenesis and period reveals that period irregularity correlates with cycle period (Figure 4V) yet this association was not present in the Nkx2.2Cre, Phox2bΔ8 group (Figure 4W). Thus, while the mutant preBötC was capable of generating inspiratory rhythms, the weaker inspiratory drive from the preBötC of Nkx2.2Cre, Phox2bΔ8 animals produces irregular activity independent of the frequency of rhythmogenesis that is normally found in control animals. These data demonstrate preBötzinger complex dysfunction in the Nkx2.2cre, Phox2bΔ8 mice.

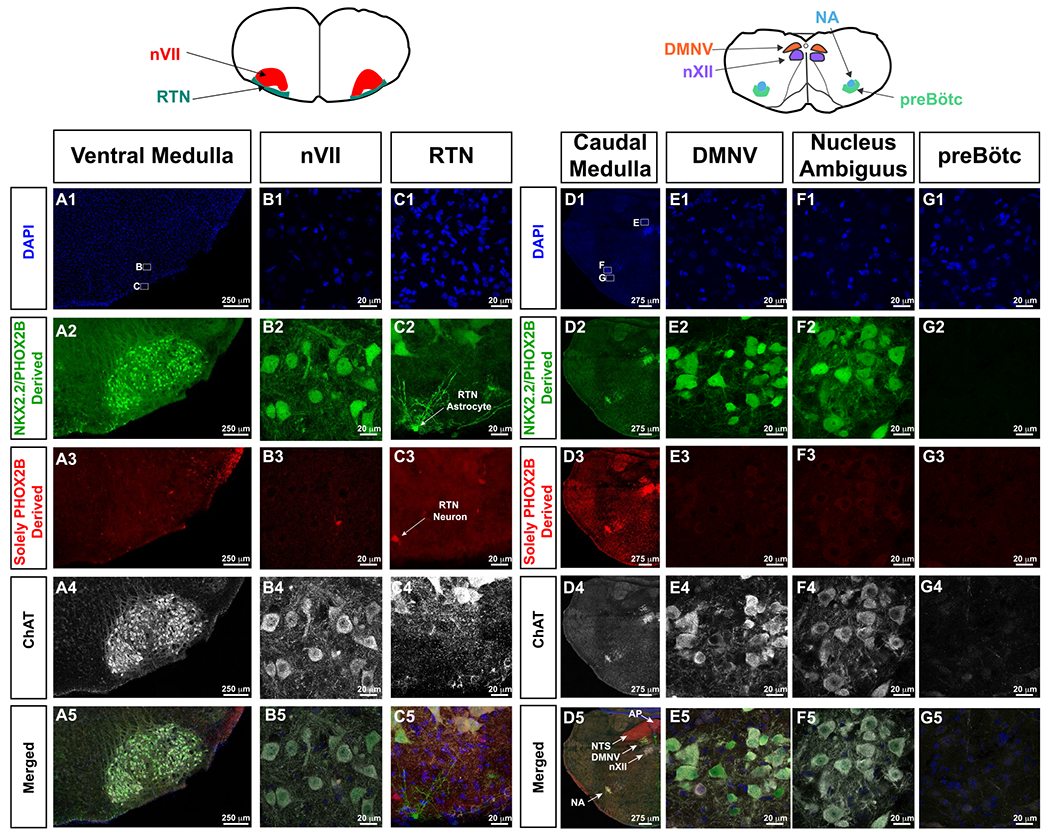

We next performed lineage tracing studies to identify the Phox2b, and Nkx2.2-derived lineages so that we could evaluate the neuropathology within an embryonic cell lineage context. To achieve this, we utilized an intersectional genetic strategy. By this strategy, flp-recombinase expression alone induces tdTomato expression, but if flp-recombinase and Cre-recombinase are expressed within the same developmental lineage, the tdTomato cassette is excised, permitting GFP expression. We performed analyses on P7 Phox2b-FLP0, Nkx2.2Cre, RC::FLTG animals. Note that the cholinergic cells of the nVII cranial nerve showed GFP expression in this animal, indicating that nVII neurons are derived from progenitor cells that express Nkx2.2 and Phox2b (Figure 5A,B). However, in the RTN, small neurons at the ventral surface show tdTomato expression (Figure 5C3 arrow), whereas a subset of RTN astrocytes show dual derivation of Nkx2.2 and Phox2b (10). In the caudal medulla, the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus nerve (DMNV) and nucleus ambiguus (Figure 5E–F), a well-characterized Phox2b-expressing neuron cluster (33), shows derivation from both Phox2b and Nkx2.2-expressing progenitor cells. The area postrema and NTS (Figure 5D5, arrows) show derivation from only Phox2b, whereas the preBötC neurons show no evidence of derivation from Nkx2.2 nor Phox2b-derived progenitor cells (Figure 5G1–G5). We, therefore, conclude that the loss of visceral motor neurons in Nkx2.2Cre, Phox2bΔ8 animals (ie, nVII, nucleus ambiguus, and dorsal motor nucleus of vagus nerve) results from cell autonomous expression of mutant Phox2bΔ8. However, the respiratory centers analyzed (RTN, and preBötC) do not show NKX2.2 derivation. We propose that the agenesis/dysfunction of these structures is due to non-cell autonomous effects on the development of these structures.

Figure 5. Lineage tracing of Nkx2.2/Phox2b-derived and Phox2b-derived cells.

For orientation, cartoons of brainstem anatomy are illustrated atop of the panels, with left cartoon pertaining to A-C, whereas right cartoon pertains to d-g. In this intersectional approach, GFP expressing cells show derivation from both Nkx2.2 and Phox2b expressing cells (second row from top), and tdTomato expressing cells are solely derived from PHOX2B expressing progenitor cells (third row from top). ChAT (white in fourth and fifth row from top) highlights cholinergic neurons. In A1 and D1, small white boxes delineate where the high magnification photomicrographs in the respective panels were obtained. In Panel C2, white arrow indicates a Nkx2.2-derived, Phox2b-derived astrocyte. Panel C3, white arrow indicates Phox2b-derived RTN neuron. Panel D5 shows the anatomy of key medullary structures including area postrema (AP, Phox2b-derived, ChAT-negative), nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS, Phox2b-derived, ChAT-negative), dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus (DMNV, Nkx2.2/Phox2b-derived, ChAT-positive), hypoglossal nucleus (nXII, not derived from Phox2b nor Nkx2.2, ChAT-positive), and nucleus ambiguus (NA, Nkx2.2/Phox2b-derived, ChAT-positive). RTN neurons are not derived from Nkx2.2, and preBötC neurons, which do not express tdTomato nor GFP do not show Nkx2.2 nor Phox2b derivation.

We next tested if we could identify any neuropathological findings in the Olig3Cre, Phox2bΔ8 mice in brainstem structures. To this end, we procured postnatal Day 0/1 (P0/1) pup brains and performed neuroanatomical analyses. Choline Acetyltransferase (ChAT) immunofluorescence was used for orientation throughout our brainstem sections. These findings are illustrated in Figure S8. We note that the dorsal rhombencephalic Phox2b-derived structures, including NTS, DMNV and area postrema (AP) were not detrimentally affected. Unsurprisingly, the nVII and RTN were unaffected as well. However, we noticed an increase of dorsal PHOX2B+ cells in the rostral brainstem of Olig3Cre, Phox2bΔ8 mice relative to controls (compare Figure S8A1,A2, quantified in Figure S8I). In view of these findings, we then performed lineage tracing by interbreeding Olig3Cre mice with ROSAtdTomato mice. Olig3 demarcates the dorsal progenitor domain in the early neural tube (60), developing spinal cord (40) and rhombencephalon (58). Olig3−/− mice show loss of NTS (35, 58) yet preservation of cerebellar architecture. No recombination was noted in the RTN, the nucleus ambiguus, and in preBötC neurons. Our experiments demonstrated robust recombination in cerebellum (Figure S8D–E), the parabrachial nucleus, and a subset of NTS cells (ranging from 5 to 15% of PHOX2B-positive NTS cells, quantified in Figure S8J). We also noted robust expression of tdTomato in the dorsal ependymal cells of the central canal as well as in the area postrema (AP) (Figure S8F1,F2,G1,G2,H1,H2), a circumventriculate organ that regulates a diverse array of physiological processes, including metabolism (reviewed by (49)). We conclude that only a subset of PHOX2B-positive NTS neurons are derived from Olig3 progenitor cells in our model, and that the AP shows strong Phox2b/Olig3 derivation.

Given the role that the AP plays in autonomic homeostasis, we were interested in exploring other potential physiological perturbations that could occur in Olig3Cre, Phox2bΔ8 mice. Lesions in the AP reportedly show defects in cardiovascular regulation, including attenuation of hypotensive pharmacologic agents (8), modulation of hypertension-inducing diets in rats (5), and regulation of mean arterial pressure (56). Furthermore, AP neurons possess both nicotinic and muscarinic acetylcholine receptors (45, 57). We, therefore, performed baseline blood pressure measurements before and following treatment with the muscarinic acetylcholine receptor agonist carbachol. These results are shown in Figure S9. Mean arterial pressure, systolic blood pressure, and diastolic blood pressure were unaffected, relative to control, in Olig3Cre, Phox2bΔ8 mice. Furthermore, Olig3Cre, Phox2bΔ8 mice responded normally to carbachol administration, showing significant lowering in blood pressure relative to baseline. We conclude that Phox2bΔ8 expression in Olig3-derived cells does not affect cardiovascular response to muscarinic agonism.

The AP has a well-documented role in metabolic regulation (reviewed by Waterson et al., (65)). We, therefore, performed metabolic analysis in a Comprehensive Lab Animal Monitoring System (CLAMS, Columbus Instruments) in Olig3Cre, Phox2bΔ8 mice during different physiological states. These factors included fed/fasted, dark/light, mutant/control, and room temperature/4 °C. We analyzed our data by performing linear regression models where VO2, VCO2, heat energy expenditure, or Activity were response variables to the aforementioned factors. The summary of these linear regression models are shown in Tables S5–S8. Although Olig3Cre, Phox2bΔ8 genotype as a factor was itself not found to significantly alter the response variables tested, we did find a significant interaction of Olig3Cre, Phox2bΔ8 status with CLAMS performed at 4° C for VO2, VCO2 and energy expenditure, but not activity. VO2, VCO2 and energy expenditure were increased in response to cold exposure in mutant, but not WT mice. Specifically, the linear regression model showed that Olig3Cre, Phox2bΔ8 status increased VO2, VCO2 and energy expenditure by 14.3% (P = 0.005), 16.6% (P = 0.0036) and 19% (P = 0.0044), respectively. This intriguing association may be due to dysfunction of PHOX2B-positive AP neurons in Olig3Cre, Phox2bΔ8 mice. We propose that metabolic regulation and temperature homeostasis shows dysfunction in Olig3Cre, Phox2bΔ8 mice.

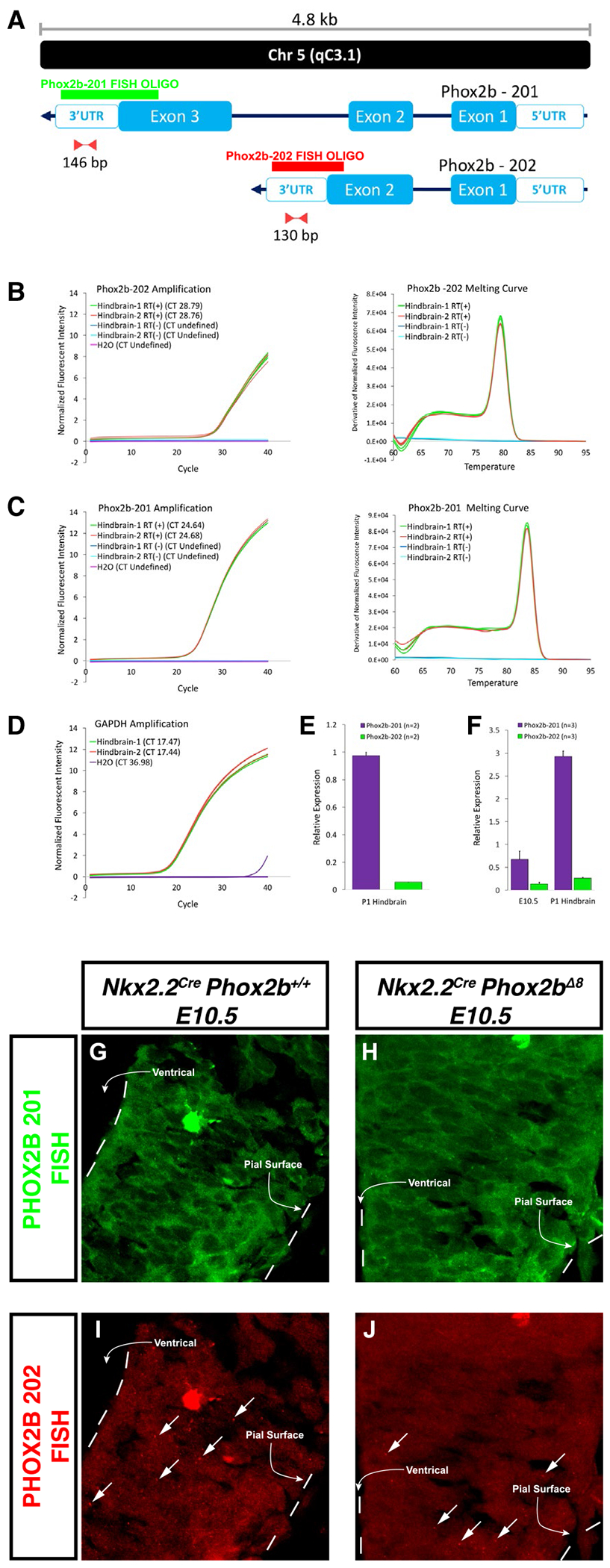

Phox2b splice variant expression in Nkx2.2Cre, Phox2bΔ8 mice

In-silico analysis of the Phox2b locus demonstrated that, in addition to the well-characterized 3-exon containing Ph0x2b mRNA fragment, a smaller transcript exists lacking the complete DNA-binding homeodomain (Ensembl number NSMUSG00000012520). Hereon we refer to the well-characterized, full-length transcript as Phox2b splice variant 1 (Phox2b-201), and the shorter mRNA transcript Phox2b splice variant 2 (Phox2b-202), as illustrated in Figure 6A. We note that many commonly utilized antibodies in the scientific literature detect an N-terminal PHOX2B epitope in common to proteins produced from Phox2b-201 and potentially Phox2b-202, or a C-terminal Phox2b epitope unique to Phox2b-201 protein products (41, 43). No antibody capable of detecting Phox2b-202 expression has been confirmed or published to our knowledge in the scientific literature. Therefore, we generated oligonucleotide primers to confirm the in-silico prediction of Phox2b-201 and -202. We demonstrate detection of this transcript at E10.5 and at P1 in Figure 6B–F. Note that under control developmental circumstances, the transcript levels of Phox2b-201 are larger than Phox2b-202 at E10.5. However, by postnatal Day 1, Phox2b splice variant 201 is further elevated relative to splice variant 202. We conclude from these qRT-PCR studies that the in-silico prediction of Phox2b-202 mRNA expression is accurate, and that the ratio of Phox2b-202/Phox2b-201 changes dynamically during development.

Figure 6. Transcriptional analysis of PHOX2B expression in developing hindbrain.

A. Schematic representation of mRNA for two splice variants described for Phox2b. Splice variants are annotated automatically by the Ensembl database and manually curated by the HAVANA group. Also depicted are the relative binding location and the amplicon length of primer pairs and probes designed to amplify and detect unique sequences at the 3′UTR region of each splice variant. B-C Amplification (left) and melting curves (right) obtained after a RT-PCR assay for Phox2b-202 (B) and Phox2b-201 (C) using cDNA samples from hindbrains of two mice at P1. Amplification curves described the cycle threshold (CT) for each sample and melting curves show the presence of a single amplicon for each primer pair. RNA samples that were not subjected to Reverse Transcriptase reaction (RT(-)) were used as negative controls. D. Amplification curve for Gapdh showing the respective CT for each sample. E. Relative expression of Phox2b-202 and Phox2b-201 obtained after analysis of the amplification curves for the two hindbrain samples. F. Expression of the two Phox2b splice variants is detected on E10.5 embryos and P1 mice. Probes targeting Phox2b-201 (G-H) and Phox2b-202 (I-J) in control and Nkx2.2cre, Phox2bΔ8 embryos, respectively. Arrows in I-J point to punctuated morphologies that are characteristic of Phox2b-202. The bright structure in G and I represents an erythrocyte.

Having confirmed the existence of Phox2b-202, we then sought to design FISH probes that could recognize both endogenous transcripts. This was necessary because our N-terminal PHOX2B antibody cannot distinguish between proteins produced from Phox2b-201, Phox2b-202, or Phox2bΔ8 protein products. In our design, we took advantages of the differences between these transcripts as the oligos designed against Phox2b- 201 would not bind to the mutant exon 3 in Phox2bΔ8. We tested for the expression of Phox2b-202 in Nkx2.2Cre, Phox2bΔ8 mice at E10.5 by RNA FISH. Phox2b-201 oligonucleotide morphology was characterized by significant granular texture in the cytoplasm of neuroepithelial cells (Figure 6G–H). In contrast, the splice variant 202 signals showed less granular cytoplasm, with markedly large punctated staining scattered throughout the neuroepithelium (Figure 6I–J). We identified both splice variants 201 and 202 in the Nkx2.2Cre, Phox2bΔ8 mice and littermate controls in the ventral neuroepithelium at E10.5, with no detectable difference noted between mutant and control groups at this age.

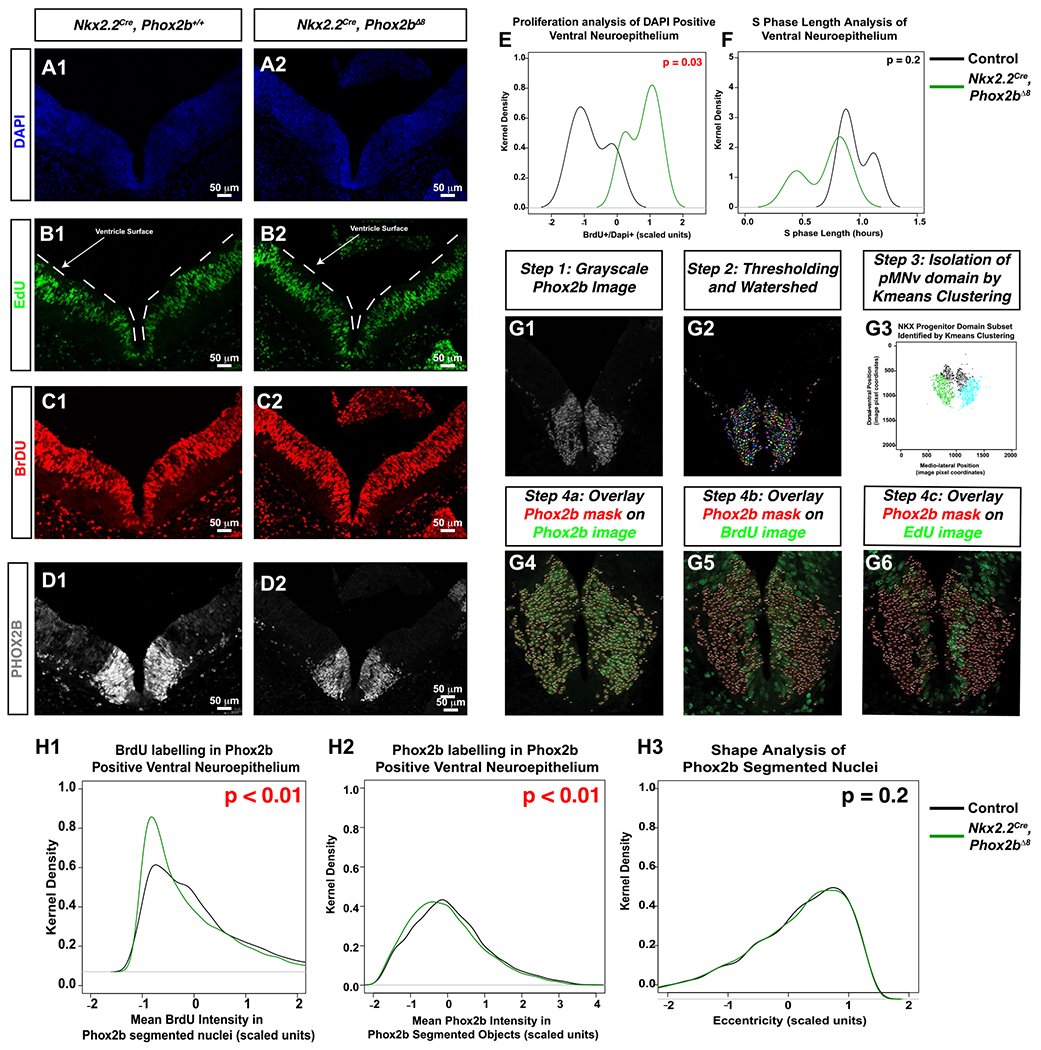

Phox2bΔ8 expression in the Nkx2.2-derived progenitor domain results in embryonic patterning changes of the ventral neuroepithelium

We next tested the extent to which Phox2bΔ8 expression in Nkx2.2-derived cells disrupts the embryonic patterning and embryonic cell cycle analysis in Nkx2.2Cre, Phox2bΔ8 mice. We generated timed pregnancies to obtain Nkx2.2Cre, Phox2bΔ8 mice and control littermates at E10.5. The analysis focused on rhombomere 4 (r4). At E10.5, rhombomere 4 shows full thickness Phox2b expression throughout ventricular and mantle zone, with Phox2b/Islet1-positive motor neurons having exited cell cycle occupying the mantle zone, and Phox2b/Nkx2.2-positive progenitor cells occupying the ventricular zone (Figure 7A1–D2).

Figure 7. Nkx2.2Cre, Phox2bΔ8 mice exhibit altered cell proliferation and disordered ventral neural tube differentiation.

A-D. Sections from E10.5 embryos at the level of rhombomere 4. A CldU-EdU pulse chase was performed in order to determine whether cell proliferation was altered in mice. CldU was administered 2 hours before administering EdU. Thirty minutes later, the animal was sacrificed and the E10.5 embryos were collected. CldU was detected using anti-BrdU antibody, and EdU detected via click-it chemistry. White lines in EdU image denote the ventricle surface. E. Proportion of BrdU positive cells over DAPI was performed, scaled, and plotted using the kernel density estimator on Y-axis and scaled value on the X-asix. A paired t-test demonstrated that Nkx2.2Cre, Phox2bΔ8 mice underwent significantly more cell proliferation during the 2.5-hour incubation with CldU than controls in the pMNv domain, although S-phase length estimation was not significantly (F). (G1-G6) Image analysis workflow from Phox2b image (G1), to segmentation (G2), isolation of pMNv domain by Kmeans clustering (G3), and overlaying Phox2b segmented nuclei as masks over the Phox2b channel (G4), BrdU channel (G5), and EdU channel (G6). H1. Kernel density estimator functions of the distribution of BrdU intensities in Phox2b segmented objects. Mutant mice show a higher proportion of Phox2b segmented objects with low BrdU mean intensities (top right shows t-test P-value comparing mean BrdU intensities amongst all Phox2b segmented objects between control and experimental groups). H2. A slight leftword shift in distribution of Phox2b mean intensities in Phox2b segmented objects in shown (top right shows t-test P-value comparing mean BrdU intensities amongst all Phox2b segmented objects between control and experimental groups). H3. Eccentricity kernel density estimation function is superimposed on control, with no statistical significance noted.

We found that at E10.5, a trend in the reduction in the number of ISLET-positive cells in the mantle zone of Nkx2.2Cre, Phox2bΔ8 embryos. This trend is represented as a decrease in percent of positively expressed ISLET cells labeled with DAPI in the mutants which approaches statistical significance by E12.5 (Supporting Table S9 – Online Resource 1). These data indicate that the statistically significant loss of ISLET1 positive visceral motor neurons identified in our E18.5 experiments may begin as early as E10.5 in Nkx2.2Cre, Phox2bΔ8 mice. Proliferation assays occurred by pulsing animals with CldU (2.5 hours) and EdU (0.5 hours), a technique permitting calculation of S-phase time in neural progenitor cells (47) as well as S-phase localization of progenitor cells (23). Note that the brief EdU pulse-labeled progenitor cells distant from the ventricular surface, whereas CldU pusling delinates signals spanning both EdU and nuclei at the ventricular surface (Figure 7B1,B2,C1,C2, note that CldU is revealed using anti-BrdU antibody). We demarcated the ventral neuroepithelium by marking the dorsal and ventral extremes of the ventral Phox2b immunoreactive region (a region that included both Phox2b+ and Phox2b− cells), and in that region counted the number of BrdU positive, EdU positive and BrdU positive/EdU negative nuclei for S-phase cycle estimation. Note that the distribution of %BrdU positive nuclei (ie, (BrdU+/Dapi+)%) is higher relative to control, indicating that Nkx2.2Cre, Phox2bΔ8 mice have more proliferation in the ventral neuroepithelim relative to controls without significant changes in S-phase (Figure 7E,F).

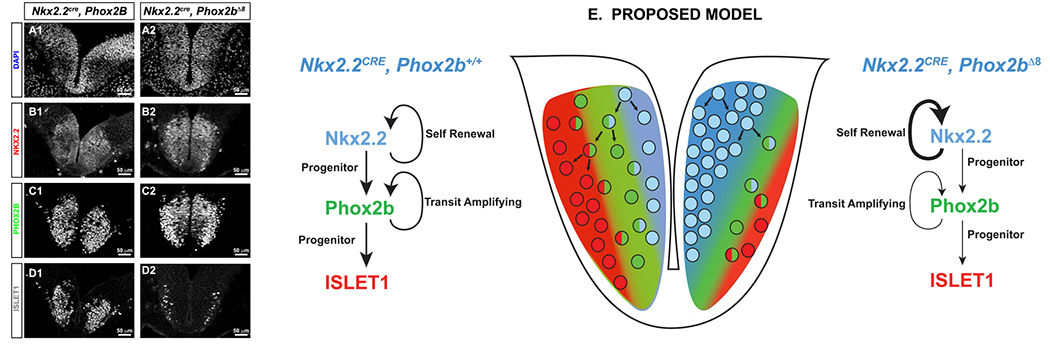

We next tested proliferation within the r4 Phox2b+ region. To achieve this, we developed an image analysis workflow which objectively segments Phox2b+ nuclei (Figure 7G1–G6, see details in Supporting Information). In brief, we used the segmented objects (representing Phox2b+ nuclei, Figure 7G1) as a mask which were overlaid over the Phox2b, EdU and BrdU image channels. This permitted us to extract imaging features in each Phox2b immunoreactive object over all the Phox2b, EdU and CldU channels. These features included intensity, Haralick texture and shape features. As an exploratory step, we generated class labels of either “experimental” (representing segmented objects from Nkx2.2cre, Phox2bΔ8 mice) or “control” groups for each segmented object. Next, we trained random forest, adaboost, support vector machine, and LDA classification algorithms on a training set composed of 70% of randomly sampled objects across all animals. We note that decision tree-based algorithms random forest and adaboost were able to show significant classification accuracy on the test set data (confusion matrixes shown in Figure S10A–D). The random forest model showed BrdU mean pixel intensity as the most important features in classification of the Phox2b segmented objects as belonging to experimental versus control groups (Figure S10E). After further evaluation, we noted that the Phox2b segmented objects from Nkx2.2cre, Phox2bΔ8 mice had a larger distribution of low BrdU pixel intensities (note the significant leftward shift in distribution of BrdU mean pixel intensity from Nkx2.2cre, Phox2bΔ8 segmented objects, Figure 7H1) with a slightly lower, albeit reaching our threshold of significance, intensity of Phox2b (Figure 7H2). In contrast, the morphological feature Eccentricity showed no statistical difference between groups, indicating that the auto-segmentation procedure had created similar object types during automated analysis (Figure 7H3). These data imply that the Phox2b+ progenitor population undergoes less proliferation in Nkx2.2cre, Phox2bΔ8 mice. Furthermore, found that at E10.5, a trend in the reduction in the number of ISLET-positive cells in the mantle zone of Nkx2.2Cre, Phox2bΔ8 embryos (Figure 8A–D). This trend is represented as a decrease in percent of positively expressed ISLET cells labeled with DAPI in the mutants which approaches statistical significance by E12.5 (Table S9). These data indicate that the statistically significant loss of ISLET1 positive visceral motor neurons identified in our E18.5 experiments may begin as early as E10.5 in Nkx2.2Cre, Phox2bΔ8 mice.

Figure 8. Experimental model of visceral motor neuron loss in CCHS.

Nkx2.2Cre, Phox2bΔ8 E10.5 embryos and controls were stained with antibodies against N-terminal PHOX2B, NKX2.2 and ISLET1 (A-E). Note the decrease in ISLET1-positive motor neurons is noted in D1. E. Proposed model of visceral motor neuron maldevelopment. Wild-type scenario is artistically rendered on left side, which illustrates a self-renewing Nkx2.2 progenitor stage, giving rise to a Phox2b positive proliferative pool with transit amplifying characteristics, which then give rise to terminally differentiated ISELT1 positive cells. In CCHS, the proliferative PHOX2B population is reduced, and there is an expansion of the Nkx2.2 proliferative population, resulting over time to a net decreased production of ISLET1 positive cells.

DISCUSSION

Proposed developmental mechanism for apneic phenotype in CCHS

The objective of this study was to elucidate developmental mechanisms by which some CCHS presentations manifest with full apnea. We tested the hypothesis that the apneic CCHS phenotype may be elicited through maldevelopment in different embryonic progenitor domains. We discovered a severe apneic phenotype in mice expressing Phox2bΔ8 in the Nkx2.2-derived progenitor domains, but not other embryological domains. While our findings show that RTN neurons and preBötC neurons are not embryologically derived from Nkx2.2, we observed Nkx2.2Cre, Phox2bΔ8 mice possess cytoarchitectural defects throughout the VRC and is accompanied by disrupted inspiratory rhythmogenesis from the preBötC. Burst duration from the preBötC of Nkx2.2Cre, Phox2bΔ8 mice is abbreviated, and the relationship between frequency and the variability of rhythmogenesis is changed. Furthermore, our inability to induce apneic phenotypes through chemogenetic silencing of Nkx2.2-derived cells underscores that dysfunction in Nkx2.2-derived neuronal networks alone does not lead to an apneic phenotype. These findings together support the notion that the cytoarchitectural defects in the VRC may be disrupting respiratory oscillators in the VRC via non-cell autonomous developmental mechanisms. Such mechanisms cause selective loss of neurons, disorganized respiratory circuits, and likely contributes to the irregular breathing pattern and severe apneic phenotype.

Expiration is a passive process and becomes active during periods of increased metabolic demand. Nkx2.2Cre, Phox2bΔ8 mutation, produces significant changes in expiration, increasing the expiratory time and decreasing the expiratory flow. An expiratory population of neurons has been described in the pFRG region (30). Evidences also suggest that the pFRG and chemosensitive neurons in the RTN may interact in a way that glutamatergic inputs from the RTN to the pFRG are necessary for the activation of the expiratory neurons during hypercapnia challenge, which is responsible for the generation of active expiratory pattern and the emergence of expiratory-related bursts in sympathetic activity (70).

Loss of RTN/pFRG neurons likely contributes to a reduced central chemoreflex and increased apnea events in these animals, compromising ventilation. Recent studies have also identified a cluster of Atoh-1 derived cells in the rostral rhombic lip (rRL) contribute to respiratory pattern derived hypoxia (24). Furthermore, the absence of RTN/pFRG also compromise innervations to the ventral respiratory column, which may affect the control of respiratory pattern generators, as well as changing the air outflow. We also note that among brainstem nuclei affected in the Nkx2.2Cre, Phox2bΔ8 mice, key structures known to modulate cardiac autonomic function undergo dysgenesis. Specifically, NA and DMNV have distinct populations of cardiac vagal preganglionic neurons, displaying crucial restraining modulation of heart rate (32, 38). As most neurons lost in Nkx2.2Cre, Phox2bΔ8 DMNV, these likely included a spectrum of vagal cardiac preganglionic neurons. These neurons densely innervate the atria, sinoatrial and atrioventricular nodal tissue and also conducting tissue, controlling the heart rate, rate of atrioventricular conduction and the strength of atrial contraction (19). Vagal innervations also project to cardiac ventricles and atria (9). In summary, considering the importance of cardiac parasympathetic activity derived from the DMNV, we cannot exclude the possibility that progressive decline of cardiac function contributes to the decreased postnatal viability at birth in Nkx2.2Cre, Phox2bΔ8 pups.

Nkx2.2 has a well-documented role in generating serotonergic neurons (20), as well as visceral motor neurons (42). Nkx2.2−/− pups breath normally at birth but die on P6 from pancreatic insufficiency (59). Nkx2.2 has a primary role in ventral embryonic patterning (4), yet Nkx2.2−/− animals do not generate defects in Phox2b-derived branchiomotor neurons, presumably through redundancy with Nkx2.9 (31). Our intersectional genetic studies show unequivocally that nVII shows derivation from both Phox2b and Nkx2.2 expressing cells. Compelling evidence in the scientific literature suggests that the location of nVII may be unimportant for proper RTN function. For instance, the human nVII nucleus is located at a position that is significantly more rostral and dorsal relative to the murine nVII. Two studies reported a cluster of PHOX2B-positive neurons adjacent to human nVII considered as candidate human RTN neurons. Lavezzi and colleagues reported cells showing cytoplasmic PHOX2B immunoreactivity located between the nVII and the superior olivary nuclear complex (34). Rudzinski and Kapur studied human fetal brains, identifying a population of PHOX2B-positive, TH-negative cells dorsolateral to the human nVII at the level of the pontomedullary junction (53). The cells in Rudzinski and Kapur’s study show relatively close apposition to the pial surface, although a significant displacement away for the glial limitans exists for this population relative to their murine counterparts. The location of the putative human RTN proposed in these two studies is similar, but the Rudzinski and Kapur cell population is located significantly more ventrolateral to that described in the Lavezzi and colleagues’ study. Nevertheless, despite human nVII localization being different, it is presumed that human RTN still functions analogously to its murine RTN counterpart. Of note, data from the reeler and scrambler mouse models, both of which show marked neuroblast migration defects, also support a role for preserved respiratory rhythm generation despite a displaced nVII. Reeler mice suffer ataxia, tremors, and impaired motor coordination due to aberrant layer formation in neocortex, hippocampus, and cerebellum resulting from mutation in the reeler gene (11,25). Scrambler mice demonstrate similar cytoarchitectural disorganization to Reeler mice (54), and suffer from mutations in the gene disabled homologue 1 (Dab1), which encodes the Dab1 adaptor protein (28,54), a component of the REELER signal transduction system. Seminal work by Rossel, and colleagues demonstrated that in both reeler and scrambler mice, the nVII migrates laterally from the neuroepithelium but does not migrate to the normal ventral position (52). As these mice survive into adulthood, respiratory rhythm generation is likely preserved, but subtle defects in respiratory control have not been explored in these mice. In summary, data from comparative neuroanatomical analyses as well as mouse models of disease offer compelling evidence that proper nVII development, even if aberrantly migrated, correlates with the presence of a respiratory rhythm. In contrast, in our CCHS model, dysgenesis of visceral motor neurons such as nVII result in an apneic phenotype. We propose that this group of neurons may serve as developmental organizers for the proper generation of respiratory oscillators. For instance, Nkx2.2-derived visceral motor neurons or glia could play an essential role in the trafficking and positioning of respiratory oscillator neurons during early embryogenic development.

Molecular mechanisms of Phox2bΔ8 induced developmental neuropathology

A potential limitation in our study is the fact that we do not identify GFP expression in the Nkx2.2cre, Phox2bΔ8 animals. Our inducible Phox2bΔ8 humanized mutation generates a bicistronic mRNA containing Phox2bΔ8 coding region, an IRES sequence, and a GFP coding region. Identification of Phox2bΔ8 is not possible by antibody-mediated immunohistochemistry. As a positive control for GFP expression, we performed side-by-side analyses with Olig3Cre, Phox2bΔ8 mice at P0/P1 which showed robust GFP expression in the dorsal rhombencephalon (Figure S11). These data indicate potentially that the Phox2bΔ8::GFP bicistronic transcript is silenced in Nkx2.2Cre, Phox2bΔ8 animals. This raises a few interesting possibilities as to how Phox2b dysfunction may occur in CCHS. We predict that either Phox2bΔ8 is expressed at very low levels with negligent transcriptional impact, or that Phox2bΔ8 is expressed and causes transcriptional dysfunction due to its aberrant C-terminus. During normal murine development, the ratio between murine Phox2b splice variant 201 and splice variant 202 is finely calibrated, with the 201/202 ratio increasing with developmental age. One mechanistic possibility to pursue is the notion that the ratio of 201:202 may be critical for proper neuron development. If this scenario was to be the cause, in Nkx2.2Cre, Phox2bΔ8 animals, dysfunctional Phox2b splice variant 201-dependent transcription, either because Phox2bΔ8 is acting as a dysfunctional transcription factor or as an absent transcription factor, would alter the physiological 201:202 ratio. We proposed (Figure 8E) that the net effect would be an increase in ventral Nkx2.2-derived cell proliferation at the expense of visceral motor neuron development. Our data point to the existence of a potential Phox2b+ transit amplifying progenitor stage located at the interface of the ventricular zone and the ISLET1-positive marginal zone. In CCHS, there is a significant decrease in CldU incorporation in the Phox2b+ progenitor cells, thereby leading to a net decrease in the Islet1+ cells. We posit that maintaining a ratio of functional 201:202 Phox2b transcripts may be critical for proper cell cycle exit of pMNv progenitor cells so that they proceed into PHOX2B-positive/ISLET-1-positive visceral motor neurons. By diminishing the Phox2b+ proliferative compartment, the visceral motor neuron pool does not develop properly. Thus, the deficits in visceral motor neurons noted at E18.5 in this CCHS model, including the NA, DMNV, and CNVII, are cell autonomous within the Nkx2.2 progenitor domain. However, the maldevelopment of these structures leads to defects in respiratory neural networks in cells not derived from the Nkx2.2 progenitor domain. These dysfunctions in respiration which mediate the majority of the CCHS phenotype are non-cell autonomous.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Justification for pooling of control genotypes.

Figure S2. Respiratory physiology of Olig3Cre, Phox2bΔ8 mice.

Figure S3. Hyperoxic hypercapnic challenge in OligCre, Phox2bΔ8 mice.

Figure S4. F, TV, and MV analysis following chemogenetic silencing of Nkx2.2-derived cells.

Figure S7. Respiratory function analysis following chemogenetic silencing of Nkx2.2-derived circuits in newborn mice.

Figure S6. PAU, PENH, EEP, EIP analysis following chemogenetic silencing of Nkx2.2-derived cells.

Figure S9. Cardiovascular physiology of Olig3Cre, Phox2bΔ8 mice.

Figure S10. Machine learning analysis of cell cycle data.

Figure S11. GFP expression analysis in Nkx2.2cre and Olig3Cre drivers.

Table S1. Genotyping primers.

Table S2. Antibodies.

Table S3. Oligonucleotide sequences used for RNA FISH probes.

Table S4. The linear model was performed in Rstudio using the model lm(f ~ Ti+Te).

Table S5. VO2 linear regression model summary.

Table S6. VCO2 linear regression model summary.

Table S7. Energy expenditure linear regression model summary.

Table S8. Activity linear regression model summary.

Table S9. Quantification of Phox2b and Islet1 positive cell on the ventral neuroepithlium.

Figure S5. Ti, Te, PIF, PEF, and EF50 analysis following chemogenetic silencing of Nkx2.2-derived cells.

Figure S8. Neuropathological findings in Olig3Cre, Phox2bΔ8 mice.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by National Institute of Health/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NIH/NHLBI R01HL132355 for CMC, JJO; R01HL138738 to KIS) and by American Heart Association (AHA) 17CSA33610078 to KIS. This research was also supported by public funding from São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) (Grants: 2016/23281-3 to ACT; 2015/23376-1 and 2015/23376-1 to TSM). TMS acknowledges 2017/12678-2 funding from FAPESP. This research was supported by (NIH/NHLBI PO1HL 144454), National Institute of Health/ The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NIH/NINDS R01 NS10742101 to AJG), and National Institute of Health/National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIH/NIDA T32DA043469 supported CCS).

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Derived data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on request.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amiel J, Laudier B, Attie-Bitach T, Trang H, de Pontual L, Gener B et al. (2003) Polyalanine expansion and frameshift mutations of the paired-like homeobox gene PHOX2B in congenital central hypoventilation syndrome. Nat Genet 33:459–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bochorishvili G, Stornetta RL, Coates MB, Guyenet PG (2012) Pre-Botzinger complex receives glutamatergic innervation from galaninergic and other retrotrapezoid nucleus neurons. J Comp Neurol 520:1047–1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bouvier J, Thoby-Brisson M, Renier N, Dubreuil V, Ericson J, Champagnat J et al. (2010) Hindbrain interneurons and axon guidance signaling critical for breathing. Nat Neurosci 13:1066–1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Briscoe J, Sussel L, Serup P, Hartigan-O’Connor D, Jessell TM, Rubenstein JL, Ericson J (1999) Homeobox gene Nkx2.2 and specification of neuronal identity by graded Sonic hedgehog signalling. Nature 398:622–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bruner CA, Mangiapane ML, Fink GD, Webb RC (1988) Area postrema ablation and vascular reactivity in deoxycorticosterone-salt-treated rats. Hypertension 11(6 Pt 2):668–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cerpa VJ, Wu Y, Bravo E, Teran FA, Flynn RS, Richerson GB (2017) Medullary 5-HT neurons: switch from tonic respiratory drive to chemoreception during postnatal development. Neuroscience 344:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng L, Chen CL, Luo P, Tan M, Qiu M, Johnson R, Ma Q (2003) Lmx1b, Pet-1, and Nkx2.2 coordinately specify serotonergic neurotransmitter phenotype. J Neurosci 23:9961–9967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collister JP, Osborn JW (1998) The area postrema does not modulate the long-term salt sensitivity of arterial pressure. Am J Physiol 275(4 Pt 2):R1209–R1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coote JH (2013) Myths and realities of the cardiac vagus. J Physiol 591:4073–4085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Czeisler CM, Silva TM, Fair SR, Liu J, Tupal S, Kaya B et al. (2019) The role of PHOX2B-derived astrocytes in chemosensory control of breathing and sleep homeostasis. J Physiol 597:2225–2251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D’Arcangelo G, Miao GG, Chen SC, Soares HD, Morgan JI, Curran T (1995) A protein related to extracellular matrix proteins deleted in the mouse mutant reeler. Nature 374:719–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dauger S, Pattyn A, Lofaso F, Gaultier C, Goridis C, Gallego J, Brunet JF (2003) Phox2b controls the development of peripheral chemoreceptors and afferent visceral pathways. Development 130:6635–6642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dubreuil V, Thoby-Brisson M, Rallu M, Persson K, Pattyn A, Birchmeier C et al. (2009) Defective respiratory rhythmogenesis and loss of central chemosensitivity in Phox2b mutants targeting retrotrapezoid nucleus neurons. J Neurosci 29:14836–14846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Durand E, Dauger S, Pattyn A, Gaultier C, Goridis C, Gallego J (2005) Sleep-disordered breathing in newborn mice heterozygous for the transcription factor Phox2b. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 172:238–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fu C, Shi L, Wei Z, Yu H, Hao Y, Tian Y et al. (2019) Activation of Phox2b-expressing neurons in the nucleus tractus solitarii drives breathing in mice. J Neurosci 39:2837–2846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Funk GD, Smith JC, Feldman JL (1993) Generation and transmission of respiratory oscillations in medullary slices: role of excitatory amino acids. J Neurophysiol 70:1497–1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garcia AJ 3rd, Dashevskiy T, Khuu MA, Ramirez JM (2017) Chronic intermittent hypoxia differentially impacts different states of inspiratory activity at the level of the preBotzinger complex. Front Physiol 8:571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garcia AJ 3rd, Zanella S, Dashevskiy T, Khan SA, Khuu MA, Prabhakar NR, Ramirez JM (2016) Chronic intermittent hypoxia alters local respiratory circuit function at the level of the preBotzinger complex. Front Neurosci 10:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Geis GS, Wurster RD (1980) Cardiac responses during stimulation of the dorsal motor nucleus and nucleus ambiguus in the cat. Circ Res 46:606–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goridis C, Rohrer H (2002) Specification of catecholaminergic and serotonergic neurons. Nat Rev Neurosci 3:531–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gray PA (2013) Transcription factors define the neuroanatomical organization of the medullary reticular formation. Front Neuroanat 7:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guyenet PG (2014) Regulation of breathing and autonomic outflows by chemoreceptors. Compr Physiol 4:1511–1562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gygli PE, Chang JC, Gokozan HN, Catacutan FP, Schmidt TA, Kaya B et al. (2016) Cyclin A2 promotes DNA repair in the brain during both development and aging. Aging 8:1540–1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van der Heijden ME, Zoghbi HY. (2018) Loss of Atoh1 from neurons regulating hypoxic and hypercapnic chemoresponses causes neonatal respiratory failure in mice. eLife 7:e38455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hirotsune S, Takahara T, Sasaki N, Hirose K, Yoshiki A, Ohashi T et al. (1995) The reeler gene encodes a protein with an EGF-like motif expressed by pioneer neurons. Nat Genet 10:77–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hirsch MR, d’Autreaux F, Dymecki SM, Brunet JF, Goridis C (2013) A Phox2b:FLPo transgenic mouse line suitable for intersectional genetics. Genesis 51:506–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hodges MR, Wehner M, Aungst J, Smith JC, Richerson GB (2009) Transgenic mice lacking serotonin neurons have severe apnea and high mortality during development. J Neurosci 29:10341–10349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Howell BW, Hawkes R, Soriano P, Cooper JA (1997) Neuronal position in the developing brain is regulated by mouse disabled-1. Nature 389:733–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang J, Colrain IM, Panitch HB, Tapia IE, Schwartz MS, Samuel J et al. (2008) Effect of sleep stage on breathing in children with central hypoventilation. J Appl Physiol 105:44–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huckstepp RT, Cardoza KP, Henderson LE, Feldman JL (2015) Role of parafacial nuclei in control of breathing in adult rats. J Neurosci 35:1052–1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jarrar W, Dias JM, Ericson J, Arnold HH, Holz A (2015) Nkx2.2 and Nkx2.9 are the key regulators to determine cell fate of branchial and visceral motor neurons in caudal hindbrain. PLoS One 10:e0124408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jordan D, Khalid ME, Schneiderman N, Spyer KM (1982) The location and properties of preganglionic vagal cardiomotor neurones in the rabbit. Pflugers Arch 395:244–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kang BJ, Chang DA, Mackay DD, West GH, Moreira TS, Takakura AC et al. (2007) Central nervous system distribution of the transcription factor Phox2b in the adult rat. J Comp Neurol 503:627–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lavezzi AM, Weese-Mayer DE, Yu MY, Jennings LJ, Corna MF, Casale V et al. (2012) Developmental alterations of the respiratory human retrotrapezoid nucleus in sudden unexplained fetal and infant death. Auton Neurosci 170:12–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu Z, Li H, Hu X, Yu L, Liu H, Han R et al. (2008) Control of precerebellar neuron development by Olig3 bHLH transcription factor. J Neurosci 28:10124–10133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Madisen L, Zwingman TA, Sunkin SM, Oh SW, Zariwala HA, Gu H et al. (2010) A robust and high-throughput Cre reporting and characterization system for the whole mouse brain. Nat Neurosci 13:133–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matei V, Pauley S, Kaing S, Rowitch D, Beisel KW, Morris K et al. (2005) Smaller inner ear sensory epithelia in Neurog 1 null mice are related to earlier hair cell cycle exit. Dev Dyn 234:633–650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McAllen RM, Spyer KM (1976) The location of cardiac vagal preganglionic motoneurones in the medulla of the cat. J Physiol 258:187–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mulkey DK, Stornetta RL, Weston MC, Simmons JR, Parker A, Bayliss DA, Guyenet PG (2004) Respiratory control by ventral surface chemoreceptor neurons in rats. Nat Neurosci 7:1360–1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Muller T, Anlag K, Wildner H, Britsch S, Treier M, Birchmeier C (2005) The bHLH factor Olig3 coordinates the specification of dorsal neurons in the spinal cord. Genes Dev 19:733–743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nobuta H, Cilio MR, Danhaive O, Tsai HH, Tupal S, Chang SM et al. (2015) Dysregulation of locus coeruleus development in congenital central hypoventilation syndrome. Acta Neuropathol 130:171–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pattyn A, Hirsch M, Goridis C, Brunet JF (2000) Control of hindbrain motor neuron differentiation by the homeobox gene Phox2b. Development 127:1349–1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pattyn A, Morin X, Cremer H, Goridis C, Brunet JF (1997) Expression and interactions of the two closely related homeobox genes Phox2a and Phox2b during neurogenesis. Development 124:4065–4075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pattyn A, Vallstedt A, Dias JM, Samad OA, Krumlauf R, Rijli FM et al. (2003) Coordinated temporal and spatial control of motor neuron and serotonergic neuron generation from a common pool of CNS progenitors. Genes Dev 17:729–737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pedigo NW Jr, Brizzee KR (1985) Muscarinic cholinergic receptors in area postrema and brainstem areas regulating emesis. Brain Res Bull 14:169–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]