Abstract

Background:

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has created barriers to the delivery of health care services, including dental care. This study sought to quantify the change in dental visits in 2020 compared to 2019.

Methods:

This retrospective, observational study examined the percent change in weekly visits to dental offices by state, nationally, and by county-level COVID incidence using geographic information from the mobile applications of 45 million cellular smartphones during 2019 and 2020.

Results:

From March to August 2020, weekly visits to dental offices were 33% lower, on average, than in 2019. Weekly visits were 34% lower, on average, in counties with the highest COVID-19 rates. The greatest decline was observed during the week of April 12, 2020, when there were 66% fewer weekly visits to dental offices. The five states with the greatest declines in weekly visits between 2019 and 2020, ranging from declines of 38 to 53 percent, included California, Connecticut, District of Columbia, Massachusetts, and New Jersey.

Conclusions:

Weekly visits to US dental offices declined drastically during the early phases of the COVID-19 pandemic. Although rates of weekly visits rebounded substantially by June 2020, rates remain about 20% lower than the prior year as of August 2020. These findings highlight the economic challenges faced by dentist due to the pandemic.

Practical Implications:

States exhibited widespread variation in rates of declining visits during the pandemic, suggesting that dental practices may need to consider different approaches to reopening and encouraging patients to return depending on location.

Keywords: access to care, dental offices, dental health services, utilization of care

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has resulted in substantial changes to the delivery of health care services. Studies have already documented declines in use of outpatient and emergency medical services in the United States (US) due to the pandemic.1, 2 Dentistry faces unique challenges in the delivery of care because common dental procedures generate droplets and aerosols, which likely contribute to the transmission of COVID-19.3, 4 Little, however, is known about how the pandemic has impacted delivery of dental care in the US.

Many dental offices closed or offered only emergency care during the spring of 2020 due to the risk of virus transmission. In the US, all states restricted dental visits in some way, generally limiting services to only emergency care.5 In surveys conducted by the American Dental Association (ADA) Health Policy Institute, 97% of responding dentists indicated that their offices were seeing emergency patients only or not seeing any patients during the week of April 6, 2020.6 By the week of September 7, 2020, about 99% of responding dentists reported being open, with 50% reporting lower patient volumes than usual.7 Additionally, a nationally representative survey of adults conducted at the end of May 2020 reported that about 75% of US adults reported delaying dental care due to the pandemic.8 However, all of these studies relied on self-reported information from surveys, which may suffer from social desirability and nonresponse biases, and most report data from only a single point-in-time. Thus, additional data and analysis are needed to determine the impact the COVID-19 pandemic on US dental care utilization.

Using aggregated geographic data obtained from cellular smartphones, the aims of this study were (1) to compare the volume of visits in dental offices between 2019 and 2020 and (2) to examine how visit volume varied by COVID-19 incidence. We hypothesized that visits to dental offices would be lower in 2020 due to the pandemic and that the decline in visits over time would be greater in communities with higher rates of COVID-19.

Methods

Data and Variables.

We used data from SafeGraph, a company which collects aggregate geographic information from the mobile applications of 45 million smartphones in all 50 states and the District of Columbia.9 These data consist of global positioning system “pings” from smartphones, which are assigned a unique anonymous identifier for each smartphone, and the time, date, latitude, and longitude of the ping. Typical sources for these data include weather and shopping applications,10 and users of these applications voluntarily agree to share geographic information. The applications providing data are not disclosed by SafeGraph. SafeGraph data has been used by others to examine consumer preferences for restaurants and, more recently, to examine community mobility, social distancing, and COVID-19 transmission.11-13 For this study, we used SafeGraph’s Core Places and Patterns files providing data for 34 weeks in 2019 and 2020 for the dates of January 6, 2019 to August 31, 2019 and January 5, 2020 to August 29, 2020. The Core Places file includes approximately 5 to 6 million business establishments identified by North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) codes, which is a large share of the estimated 7 to 10 million establishments nationally.14 All places in the data are assigned one NAICS code and we identified dental offices using NAICS code 6212. Among the 140,749 unique places identified by NAICS code 6212 in our dataset, we excluded 2,230 places (1.6% of the total sample) that, based on name and Google search, appeared unlikely to be dental offices. By linking the Core Places and Patterns files, we were able to examine visits to dental offices.

We obtained ZIP code-level data from the 2019 Novel Coronavirus Visual Dashboard operated by the Johns Hopkins University Center for Systems Science and Engineering to examine variation in visits by local severity of the pandemic as of August 29, 2020.15 We constructed county-level counts of COVID-19 cases per 100,000 population using population estimates from the American Community Survey.16

Analysis.

First, we examined the percent change in weekly visits to dental offices nationally and by state. We calculated the percent difference in weekly visits to dental offices identified in SafeGraph data from the week of January 5, through the week of August 23, 2020, relative to the week of January 6, through the week of August 25, 2019. To illustrate the state-level findings, we stratified states into quartiles based on the percent difference in visits between 2019 and 2020.

Second, we examined if visit volume varied by COVID-19 incidence. To do so, we used information on the county location of dental offices and then constructed terciles to stratify counties by COVID-19 incidence per 100,000 residents as of August 29, 2020. We constructed these terciles due to the distribution of the data and for ease of interpretation of results. We plotted the change in weekly visits to dental offices over time. We then estimated a linear regression model to examine if the percent change in weekly visits from 2020 to 2019 was significantly different in counties by tercile of the county-level COVID-19 incidence rate during the pandemic. The dependent variable was the percent change in weekly visits from 2020 to 2019 in weeks of March 8, 2020 and after compared to the same time period in 2019. The key explanatory variable was the tercile of county level-COVID-19 incidence (reference group = counties in lowest tercile of COVID-19 incidence). The model was estimated with robust standard errors.

All analyses were conducted using Stata MP (Version 16.1, College Station, Texas). This study was deemed exempt by our Institutional Review Board. No patient consent was required for this research, as the data were anonymous without personal identifiers or contact information.

Results

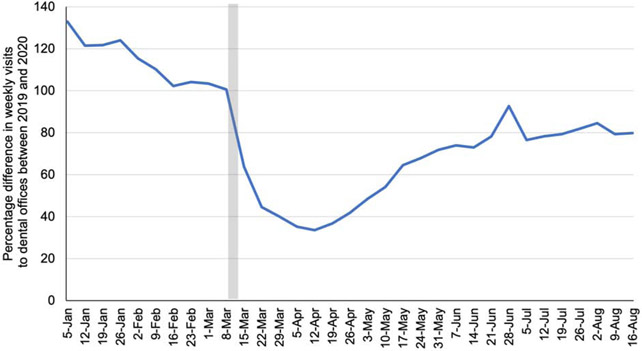

The analytic dataset included 43,328,712 total visits to dental offices from January 5 to August 29, 2020 and 55,398,871 total dental visits during the same time period in 2019. The largest number of visits, during both 2019 and 2020, was observed in Texas, California, and New York. On March 13, 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic was declared a national emergency in the US.17 Nationally, weekly visits to dental offices were 15% higher, on average, in the weeks prior to the declaration of a national emergency (January 5 to March 7, 2020) than in the corresponding weeks during 2019 (Figure 1). From the week of March 8 through the week of August 23, 2020, weekly visits to dental offices were 34% lower, on average, than in the corresponding weeks during 2019. The greatest decline in weekly visits compared to 2019 was observed during the week of April 12, 2020, when there were 66% fewer weekly visits to dental offices.

Figure 1. Percent differences in weekly visits to dental offices between 2019 and 2020.

Number of weekly visits to dental office was tracked using smartphone location data. The percent changes were centered at 100 for ease of interpretation. The gray bar illustrates that the COVID-19 pandemic was declared a national emergency in the US on March 13, 2020.

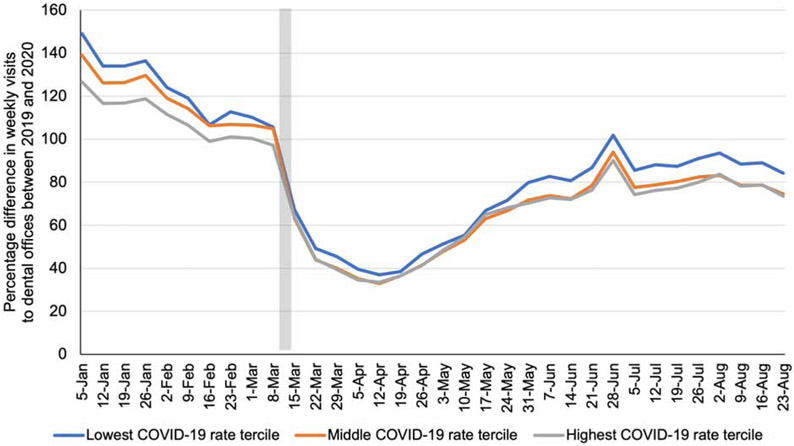

At the state-level, among the 13 states (i.e., top quartile) experiencing the greatest declines in weekly visits to dental offices following the declaration of a national emergency, most were located in the Northeast (n=5) and South (n=4) US Census regions (Figure 2). The five states with the greatest declines in weekly visits between 2019 and 2020, ranging from declines of 38 to 53 percent, included California, Connecticut, District of Columbia, Massachusetts, and New Jersey. The greatest decline was observed in the District of Columbia, which experienced a 53% decline in weekly visits. Among the states in the bottom quartile experiencing the smallest declines in weekly visits to dental offices following the declaration of a national emergency, most were located in the South (n=8) US Census region.

Figure 2. State-level percent differences in weekly visits to dental offices during March to August between 2019 and 2020.

Map reflects the state-level unadjusted differences in weekly visits to dental offices from March 8 through the week of August 23, 2020 compared to the same weeks in 2019. Weekly visits to dental office were tracked using smartphone location data.

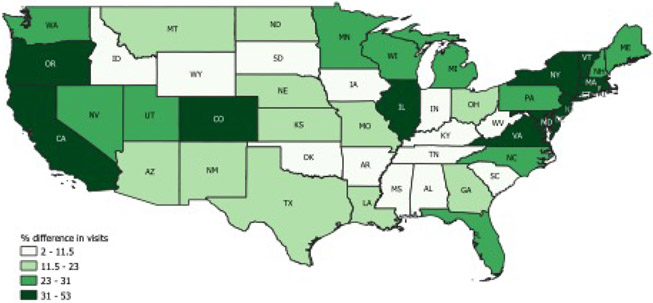

When examined by county level-COVID-19 incidence, the decline in weekly visits was slightly higher in those counties most impacted by COVID-19 (Figure 3). From the week of March 8 through the week of August 23, 2020, weekly visits to dental offices were 35% lower, on average, than in the corresponding weeks during 2019 in counties with the highest COVID-19 rates. During this same time period, weekly visits were 27% lower, on average, than in the corresponding weeks during 2019 in counties with the lowest COVID-19 rates. Results from the regression model allow us to compare the difference in visits between 2019 and 2020 in counties after the declaration of a national emergency (Appendix Table 1). As indicated by the intercept in the regression model, weekly visits declined by 0.8% on average during the pandemic for counties with the lowest COVID-19 incidence. The average decline in weekly visits during the pandemic was 5.7% greater in counties with the highest COVID-19 incidence compared to counties with the lowest COVID-19 incidence (95% Confidence Interval (CI)= −7.8 to −3.7, P<0.001). The average decline in weekly visits during the pandemic was 8.3% greater in counties in the middle tercile COVID-19 incidence compared to counties in the lowest tercile of COVID-19 incidence (95% CI= −10.1 to −6.5, P<0.001).

Figure 3. Percent differences in weekly visits to dental offices between 2019 and 2020, by cumulative county-level COVID-19 incidence rate per 100,000 population tercile.

Number of weekly visits to dental office was tracked using smartphone location data. The percent changes were centered at 100 for ease of interpretation. County-level COVID-19 incidence rates per 100,000 population were estimated using data from the Johns Hopkins University Center for Systems Science and Engineering, as of August 29, 2020. The gray bar illustrates that the COVID-19 pandemic was declared a national emergency in the US on March 13, 2020.

Discussion

From March to August 2020, there was a large decline in the number of weekly visits to dental offices compared to the corresponding period in 2019. The largest decline was observed during April, a time when many states were encouraging social distancing to avoid the spread of the virus. Visits to dental offices increased through early July but declined again and were 20% lower than the prior year’s rates of weekly visits at the end of August. Although surveys of providers and patients have indicated that the COVID-19 pandemic led to fewer dental visits,6, 8 this is the first study, to our knowledge, to directly compare the volume of visits in 2019 and 2020 and to use objective data unaffected by self-reporting biases.

Visits to dental offices may have declined during the spring and summer of 2020 for several reasons. First, many dental offices closed during this time in response to mandates and recommendations issued by states and state dental societies that dental offices provide only urgent care.5 Second, even when offices were open, patients may have cancelled or delayed visits due to fear about contracting COVID-19, a fear that has been well-documented by media outlets.18, 19 A recent survey of US dentists, however, reported that fewer than 1% of dentists had COVID-19 within the past month, nearly all dentists had implemented enhanced infection control efforts, and 73% of dentists reported using personal protective equipment, as recommended by the US Centers for Disease Control.20 Finally, even before the pandemic, 13% of non-elderly adults reported financial barriers to receiving dental care, which was higher than any other type of health care,21 and pandemic-related economic uncertainty may further encourage patients to avoid or delay dental care due to cost.

The ADA recommended postponing elective procedures as of March 16 and all states had some level of closure or reduced services, primarily in March and April.5,22 We found declines in visits to dental offices following declaration of a national emergency across all three terciles of COVID-19 incidence per 100,000 county population. While all communities were likely impacted by reductions in dental services regardless of the severity of the pandemic, we observed larger declines in counties with higher COVID-19 rates as compared to counties with the lowest COVID-19 rates. These findings may be driven by closures of dental offices in areas most affected by the pandemic or patient choices to delay care due to fear of COVID-19. There may also be other characteristics of the communities most affected in the early months of the pandemic that explain this difference. Future studies should examine the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic over a longer period on dental services, as well as how pre-pandemic levels of access to dentists is associated with declines in dental visits during the pandemic, as well as other factors such as socioeconomic status and the percentage of routine users of dental care in a community.

Further, the pandemic has disproportionally hurt racial/ethnic minority and low-income populations23 —populations that are also disproportionally impacted by dental caries and have low rates of dental visits.24, 25 A survey of US adults conducted in May 2020 reported no difference in delayed dental care due to the pandemic by race and ethnicity;8 however, the survey sample was small and did not allow for stratification. Unfortunately, the data used in this study lack information on individual characteristics, preventing us from examining this important issue. Further research is needed to understand if historically disadvantaged populations are differentially impacted by declines in visits to dental offices, and those studies can potentially utilize information on the distribution of racial/ethnic groups at the community-level. In the interim, efforts to monitor and facilitate dental care access for historically disadvantaged populations during and after the pandemic are needed.

This study highlights the economic challenges of the pandemic for dentists, as declines in visits correspond to lost revenue. The ADA Health Policy Institute estimates that dental care spending may decline by up to 38% in 2020, which aligns with our finding that visits to dental offices declined by an average of 33% since March 8, 2020.26 Lost revenue may have immediate impacts, as more than half of dental practices are solo practices.27 Federal funding has been made available to dental practices experiencing economic challenges due to the pandemic, including Paycheck Protection Program loans, Economic Injury Disaster Loans, and grants via the Provider Relief Payment Fund for eligible providers who participate in Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program.28, 29 Whether this funding will be sufficient to sustain dental practices remains unclear.

This study should be interpreted in the context of its limitations. SafeGraph data provide information on a large national sample of individuals, representing about 10% to 15% of smartphones in the US, but does not represent individuals without smartphones.30 SafeGraph acquires mobile location data through voluntary user opt-ins. Research indicates willingness to opt-in to disclose personal information typically declines with age, so these results may be more representative of younger populations.31 Additionally, the smartphones included in the dataset may change over time as users install and remove applications, thus our findings are likely suggestive of societal trends rather than the behavior of specific individuals. Furthermore, we used “pings” from smartphone visits to dental offices, identified using NAICS code 6212. These “pings” were used as proxies for dental visits and we were unable to distinguish between visits made by staff and patients, and we cannot determine what type of treatments patients may have received during visits. If dental offices were underrepresented in these data, we may undercount dental visits. However, as this would impact both 2019 and 2020, we would not expect this to impact the percent change in weekly visits to dental offices over time. Further, while we took care to exclude places identified by NAICS code 6212 that were unlikely to provide dental care, e.g., labs making dental materials, this code may be an imprecise identifier of dental offices. We also lacked information on county-level COVID-19 rates for some counties in Utah and Massachusetts, and instead used rates aggregated across counties. Finally, we did not account for state-specific stay-at-home orders or regulations and recommendations for the closure and safe-practice of dentistry during the pandemic. As was noted earlier, state-level and ADA guidance encouraged some level of closure or reduced services in dental offices during March and April 2020, 5,22 indicating all states were impacted by closures.

This study provides important information about declines in weekly visits to US dental offices in 2020. Although rates of weekly visits were about 60% lower during April 2020 than April 2019, by early August, rates had rebounded somewhat and were about 20% lower than in the prior year. States exhibited widespread variation in declining visits, suggesting that dental practices may need to consider different approaches to reopening and encouraging patients to return depending on location.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research [grant numbers R01 DE026136-03 and R01 DE028530-01A1]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research or the National Institutes of Health. The funding source had no involvement in study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; the writing of the report; nor in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hartnett K, Kite-Powell A, DeVies J. National Syndromic Surveillance Program Community of Practice: Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on emergency department visits—United States, January 1, 2019–May 30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69(23):699–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mehrotra A, Chernew M, Linetsky D, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on outpatient care: visits return to prepandemic levels, but not for all providers and patients. New York, NY: The Commonwealth Fund; 2020. "https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/2020/oct/impact-covid-19-pandemic-outpatient-care-visits-return-prepandemic-levels". Accessed October 23, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Izzetti R, Nisi M, Gabriele M, Graziani F. COVID-19 transmission in dental practice: brief review of preventive measures in Italy. J Dent Res 2020;99(9):1030–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meng L, Hua F, Bian Z. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Emerging and future challenges for dental and oral medicine. J Dent Res 2020;99(5):481–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Dental Association. COVID-19 State Mandates and Recommendations. Chicago, IL: American Dental Association; 2020. "https://success.ada.org/en/practice-management/patients/covid-19-state-mandates-and-recommendations". Accessed October 15, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 6.ADA Health Policy Institute. COVID-19: Economic Impact on Dental Practices Week of June 1 Results. Chicago IL: American Dental Association; 2020. "https://surveys.ada.org/reports/RC/public/YWRhc3VydmV5cy01ZWQ2NjRiNzBhNzI3MTAwMGVkMDY2ZTQtVVJfNWlJWDFFU01IdmNDUlVO". Accessed July 10, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 7.ADA Health Policy Institute. COVID-19: Economic Impact on Dental Practices Week of September 7 Results. Chicago, IL: American Dental Association; 2020. "https://iad1.qualtrics.com/reports/RC/public/YWRhc3VydmV5cy01ZjU3OWI5NzkzZDE2YTAwMTYzMjBmZWUtVVJfM3BaeGhzWm12TnNMdjB4". Accessed October 21, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kranz AM, Gahlon G, Dick AW, Stein BD. Characteristics of US adults delaying dental care due to the COVID-19 pandemic. JDR Clin Trans Res 2020. doi: 10.1177/2380084420962778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.SafeGraph. Determining point-of-interest visits from location data: a technical guide to visit attribution. San Francisco, CA: SafeGraph; 2020. "https://uploads-ssl.webflow.com/5baafc2653bd67278f206724/5d939e761d397862e80013c0_SafeGraph%20Technical%20Guide%20To%20Visit%20Attribution.pdf". Accessed September 21, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andersen M, Bryan S, Slusky D. COVID-19 surgical abortion restriction did not reduce visits to abortion clinics. NBER Working Paper 2020;(28058). "https://www.nber.org/papers/w28058". Accessed January 7, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Athey S, Blei D, Donnelly R, Ruiz F, Schmidt T. Estimating heterogeneous consumer preferences for restaurants and travel time using mobile location data. Paper presented at: AEA Papers and Proceedings, 2018. "https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/pandp.20181031". Accessed October 26, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lasry A, Kidder D, Hast M, et al. Timing of community mitigation and changes in reported COVID-19 and community mobility—four US metropolitan areas, February 26–April 1, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69(15). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Narayanan RP, Nordlund J, Pace RK, Ratnadiwakara D. Demographic, jurisdictional, and spatial effects on social distancing in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS One 2020;15(9):e0239572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crane LD, Decker RA, Flaaen A, Hamins-Puertolas A, Kurz C. Business Exit During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Non-Traditional Measures in Historical Context. Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2020-089. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 15.COVID-19 data repository by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University; 2020. "https://github.com/CSSEGISandData/COVID-19/blob/master/README.md". Accessed October 6, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Community Survey 2014-2018 5-year estimates now available. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2019. "https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2019/acs-5-year.html". Accessed October 6, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Trump DJ. Message to the Congress on declaring a national emergency concerning the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. Washington, DC: White House; 2020. "https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/message-congress-declaring-national-emergency-concerning-novel-coronavirus-disease-covid-19-outbreak/". Accessed October 23, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kritz F The dentist will see you now. but should you go? Washington, DC: National Public Radio; 2020. "https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2020/07/06/886456835/the-dentist-will-see-you-now-but-should-you-go". Accessed October 15, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cramer M Is it safe to go back to the dentist? New York, NY: New York Times; 2020. "https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/25/health/dentist-coronavirus-safe.html". Accessed October 15, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Estrich CG, Mikkelsen M, Morrissey R, et al. Estimating COVID-19 prevalence and infection control practices among US dentists. J Am Dent Assoc 2020;151(11):815–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vujicic M, Buchmueller T, Klein R. Dental care presents the highest level of financial barriers, compared to other types of health care services. Health Aff 2016;35(12):2176–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burger D ADA recommending dentists postpone elective procedures. 2020. "https://www.ada.org/en/publications/ada-news/2020-archive/march/ada-recommending-dentists-postpone-elective-procedures". Accessed October 20 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moore JT, Ricaldi JN, Rose CE, et al. Disparities in incidence of COVID-19 among underrepresented racial/ethnic groups in counties identified as hotspots during June 5–18, 2020—22 states, February–June 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69(33):1122–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin M, Griffin SO, Gooch BF, et al. Oral health surveillance report: trends in dental caries and sealants, tooth retention, and edentulism, United States: 1999–2004 to 2011–2016. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2019. "https://www.cdc.gov/oralhealth/pdfs_and_other_files/Oral-Health-Surveillance-Report-2019-h.pdf". Accessed October 26, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang Y Racial/ethnic disparity in utilization of general dental care services among US adults: Medical Expenditure Panel Survey; 2012. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities 2016;3(4):565–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nasseh K, Vujicic M. Modeling the impact of COVID-19 on U.S. dental spending — June 2020 update. Chicago, IL: American Dental Association; 2020. "https://www.ada.org/~/media/ADA/Science%20and%20Research/HPI/Files/HPIBrief_0620_1.pdf". Accessed October 26, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 27.ADA Health Policy Institute. How many dentists are in solo practice? Chicago, IL: American Dental Association; 2020. "https://www.ada.org/~/media/ADA/Science%20and%20Research/HPI/Files/HPIgraphic_1018_1.pdf?la=en". Accessed October 15, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 28.American Dental Association. Fact Sheet: Small Business Administration loans for dentists. Chicago, IL: American Dental Association; 2020. "https://www.ada.org/~/media/CPS/Files/COVID/ADA_ADCPA_SBA_Loan.pdf". Accessed October 16, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 29.HHS Assistant Secretary for Public Affairs. CARES Act Provider Relief Fund: general information. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2020. "https://www.hhs.gov/coronavirus/cares-act-provider-relief-fund/general-information/index.html". Accessed October 16, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Squire RF. What about bias in the SafeGraph dataset? San Francisco, CA: SafeGraph; 2019. "https://www.safegraph.com/blog/what-about-bias-in-the-safegraph-dataset". Accessed October 21, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goldfarb A, Tucker C. Shifts in privacy concerns. Am Econ Rev 2012; 102(3):349–53. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.