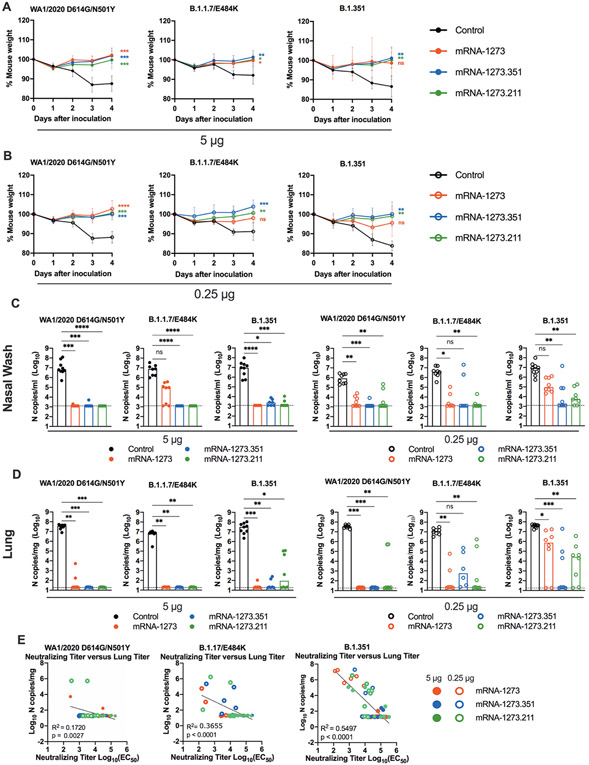

Fig. 2. mRNA vaccination confers protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection after in 129S2 mice.

Seven to nine-week-old female 129S2 mice were immunized and boosted with 5 or 0.25 μg of mRNA vaccines as described in Fig. 1A. Three weeks after boosting, mice were challenged by intranasal inoculation with 105 focus-forming units (FFU) of WA1/2020 N501Y/D614G, B.1.1.7/E484K, or B.1.351. (A and B) Body weight change was measured over time. Data shown is the mean ± SEM (n = 6 to 9 mice per group, two experiments). Data were analyzed by a one-way ANOVA of the area under the curve from 2 to 4 dpi with Dunnett’s post-test; comparison to control immunized group: ns, not significant; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001). (C and D) Viral burden at 4 dpi in the nasal washes (C) and lungs (D) was assessed by qRT-PCR of the N gene after challenge of immunized mice (n = 6 to 8 mice per group, two experiments). Boxes illustrate median values, and dotted line shows LOD. Data were analyzed by a one-way Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA with Dunn’s post-test; comparison among all immunization groups: ns, not significant; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001). (E) Correlation analyses are shown comparing serum neutralizing antibody concentrations three weeks after boosting plotted against lung viral titer (4 dpi) in 129S2 mice after challenge with the indicated SARS-CoV-2 strain. EC50, half maximal effective concentration. Pearson’s correlation P and R2 values are indicated as insets. Closed symbols, 5 μg vaccine dose; open symbols, 0.25 μg vaccine dose.