Abstract

Objective:

The predominant mechanism driving hyperuricemia in gout is renal uric acid underexcretion, yet the standard urate-lowering therapy (ULT) recommendation is first line xanthine oxidase inhibition (XOI) irrespective of the cause of hyperuricemia. Here, we conducted a comparative effectiveness clinical trial of first line un-titrated, low-dose benzbromarone uricosuric therapy vs. XOI ULT with low-dose febuxostat in gout with renal uric acid underexcretion.

Methods:

A prospective, randomized, single-center, open-labeled trial of men with gout and renal uric acid underexcretion (defined as fractional excretion of urate <5.5% and uric acid excretion ≤600 mg/day/1.73m2) was conducted. We randomly assigned 196 participants to low-dose benzbromarone 25 mg daily (LDBen) or low-dose febuxostat 20 mg daily (LDFeb) for 12 weeks. All participants received daily urine alkalization with oral sodium bicarbonate. The primary endpoint was rate of achieving serum urate (SU) target <6 mg/dL.

Results:

More participants in the LDBen group achieved the serum urate target than LDFeb (61% vs. 32%, P<0.001). Adverse events, including gout flares and urolithiasis, did not differ between groups, with the exception of more transaminase elevation in the LDFeb group (LDBen 4% vs. LDFeb 15%, P=0.008).

Conclusion:

Compared to LDFeb, LDBen had superior urate-lowering and similar safety in the relatively young and healthy patients with gout of renal uric acid underexcretion type.

Keywords: Benzbromarone, URAT1, Febuxostat, Urate-lowering therapy

INTRODUCTION

In gout, increased serum urate (SU), termed hyperuricemia, promotes deposition of monosodium urate crystals in articular and peri-articular structures, which can trigger acute episodes of very painful inflammatory arthritis (gout flare) (1, 2). Long-standing hyperuricemia and gout also can lead to palpable tophi, joint damage, and urolithiasis (1). Urate-lowering therapy (ULT) is the central strategy for effectively controlling hyperuricemia and gout (3–5). However, pathophysiology of hyperuricemia is heterogeneous in gout patients (6–10).

Renal uric acid underexcretion is the dominant cause of hyperuricemia (~70%−90% of gout patients) (7). However, uric acid overproduction and intestinal uric acid underexcretion with renal uric acid overload also can drive hyperuricemia alone or in combination with renal uric acid underexcretion in gout (6, 8–10). Ichida and Matsuo et al. (9) have developed criteria to classify hyperuricemia in gout into uric acid overproduction, renal uric acid underexcretion, extra-renal uric acid underexcretion, and combined mechanism types, via clinical and genetic test results, and via fractional excretion of urate (FEUA) and uric acid excretion (UUE) under low purine diet conditions. As such, FEUA less than 5.5% and UUE less than or equal to 600 mg/day/1.73m2 is used as criteria to define the renal uric acid underexcretion subset of gout (9).

The principal oral ULT agents are the XOI drugs allopurinol and febuxostat, and uricosuric agents that all act as inhibitors of the renal urate transporter URAT1 (benzbromarone and probenecid) (11–14). Based on available evidence to date, the 2020 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and 2016 European Congress of Rheumatology (EULAR) gout management guidelines recommend XOI using allopurinol as the first line ULT approach (12, 13). Whereas 2016 EULAR guidelines support uricosuric therapy as a second line ULT option in gout, 2020 ACR guidelines only provide conditional recommendation for probenecid use as a second line agent after allopurinol failure and benzbromarone is not part of that clinical guidance since the drug is not approved in the USA (12, 13). Allopurinol, febuxostat, and benzbromarone all in broad use in Asia, and comparably effective in achieving serum urate target and gout flare burden reduction in ULT treat-to-target dose titration studies in Asian study populations, the prevalence of HLA-B*5801 that is associated with allopurinol hypersensitivity reaction is higher in Han Chinese, Korean, and Thai descent (7.4%) (11, 12, 15–18). Notably, febuxostat is a recommended ULT drug in China, but at a dose of only 20–40 mg daily (13, 19). Moreover, a randomized controlled trial in Chinese gout patients that was not separated by the pathophysiology driving hyperuricemia used a 20 mg daily febuxostat dose, a quarter of the maximum approved in the USA (and a sixth of the maximum dose prescribed outside the USA), and benzbromarone 25 mg daily (a quarter of the typical maximum dose used in practice, and an eighth of the maximum advised dose that most often is used with moderate to severe renal impairment), the rate of achieving the serum urate target was similar with these low dose regimens (15), here termed “LDFeb” and “LDBen”.

We hypothesized that LDBen had superior urate-lowering and similar safety compared to first-line LDFeb in gout patients with renal uric acid underexcretion. The aim of this randomized controlled trial was to compare efficacy and safety of to treat gout of the renal uric acid underexcretion type.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study design and participants.

This was an open-labeled, prospective, randomized study, conducted in the Gout Clinic of the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University. We compared the efficacy and safety of LDBen and LDFeb in men with renal underexcretion type gout underwent 12 weeks of ULT. Inclusion criteria were: gout according to the 2015 ACR/EULAR gout classification criteria (19), male, age ranging from 18 years to 70 years, the levels of SU between 7.0 mg/dL and 10.0 mg/dL, and renal underexcretion. Renal underexcretion type defined as FEUA<5.5% and UUE≤ 600 mg/day/1.73m2 (9). Participants were excluded if one of the following criteria was met: FEUA ≥5.5% or UUE>600 mg/day/1.73m2; experiencing a gout flare within 2 weeks before enrollment; urinary calculi; elevated transaminases (>2.0 times of the upper normal limit); eGFR<60 ml/min/1.73m2; need to take any urate-lowing drug or other medicine affecting the serum urate (Supplement Table1). The ethics committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University approved the trial. The trial was registered at the Chinese Clinical Trial Registration Center (#ChiCTR1900022981). All participants provided written informed consent.

Treatment and procedures.

As described in the previous study (16), all enrolled participants underwent a 14-day washout period, which stopped taking urate-lowering drugs and followed a low-purine diet. During the study, other urate-lowering drugs or drugs that were known to affect the SU level were prohibited. Random number generator created a randomization list. Participants were given a random code and were randomized 1:1 to one of the following: “LDBen” or “LDFeb”. Participants took oral febuxostat or benzbromarone once daily in the morning. All participants received daily urine alkalization with oral sodium bicarbonate, dosed at 1 gram three times daily. During study drug treatment, colchicine and/or NSAIDs were given to participants if they developed a gout flare. For participants with serum transaminase elevation higher than a doubling, hepatoprotective treatment (diammonium glycyrrhizinate, silibinin, or polyene phosphatidyl choline) was prescribed.

Random number generator created a randomization list and participants were given a random code. The clinician does not know which treatment option a participant would receive before randomization. Both the participant and the treating clinician knew the allocation of treatment. The participants were given advice on non-drug treatment, including diet, exercise, etc.

Information at the baseline including age, onset age, duration, lifestyles, body weight, height, body mass index (BMI, weight/height2, kg/m2), disease history (tophus, hypertension, fatty liver, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, cardiovascular disease), family history of gout were collected. Serum biochemical index included SU, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), fasting blood glucose (FBG), triglyceride (TG), cholesterol (TC), creatinine (Cr) was collected. The renal function was assessed by eGFR (CKD-EPI design formulas, eGFR (ml/min/1.73m2) = 141×(Cr/0.9)c×(0.993) age(year), Cr ≤ 80 μmol/L (0.9 mg/dL), c = −0.411; Cr > 80 μmol/L (0.9 mg/dL), c = −1.209), Clinically obesity was defined as BMI ≥ 28 kg/m2, based on Chinese criteria (20, 21). We measured the biochemistry parameters at every visit. Participants would be determined as withdrawn cases with three consecutive days without medication.

Outcomes.

The primary efficacy outcome was the rate of achieving target SU<6.0 mg/dL in week 12 of treatment. Secondary efficacy outcomes were the rate of achieving target SU<5.0 mg/dL, the change of SU (ΔSU%, (baseline SU-visit SU)/baseline SU), and changes of other laboratory parameters including SU, FBG, TC, TG, AST, ALT, Cr, eGFR. Safety outcomes included the incidence of gout flares, and the percentage of participants with treatment-emergent adverse events. Changes in renal function, changes in liver function, and urolithiasis were adverse events of particular interest in this study.

Sample size.

The sample size for this study was determined based on the primary endpoint (the rate of achieving target SU<6.0 mg/dL in week 12 of treatment). Based on previous studies and the preliminary study, we estimated that the rate of achieving serum urate target would be 60.% in the LDBen group and 38.% in the LDFeb group in this study (15, 16). We calculated that a sample size of 78 per group would be required according to a 5% two-sided significance level and 80% power to detect the difference between the LDBen group and LDFeb group (1:1 allocation). A sample size of 98 for each group was calculated to account for an estimated 20% dropout rate.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 22.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). All continuous variables were presented as mean (standard deviation, SD) or median (interquartile range, IQR) and categorical variables as percentages. Independent samples t-test or Mann-Whitney U was used to compare of continuous variables and chi-squared test (χ2 test) for categorical variables between the two groups. Variables from each visit within the group were compared to baseline using paired samples t-test or Wilcoxon signed ranks test. P value<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Study flow and clinical characteristics.

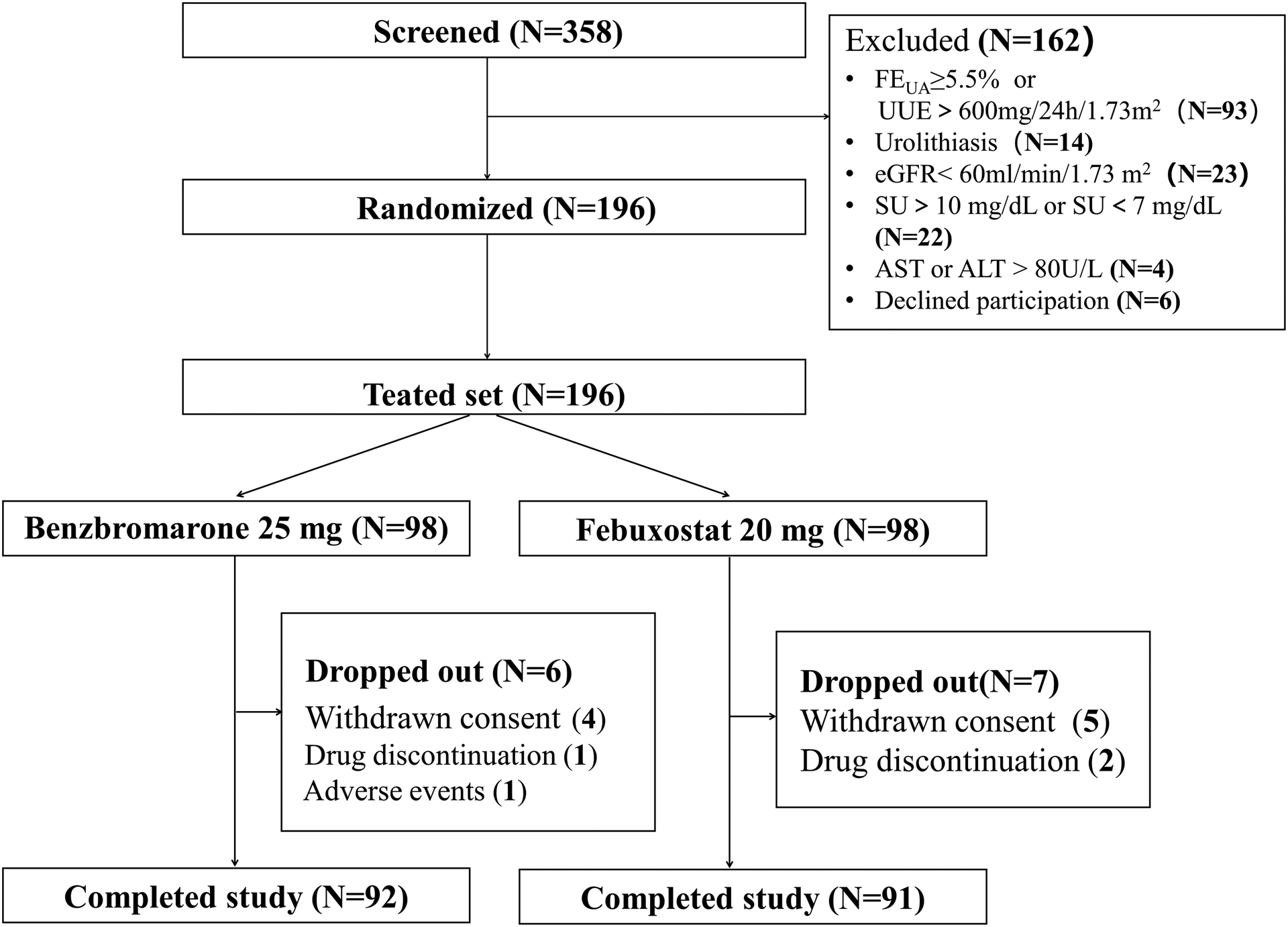

The clinical trial was initiated on 3 May 2019 and completed on 26 January 2021. A total of 196 participants was randomized to receive ULT with “LDBen” (N=98) or “LDFeb” (N=98) (Figure 1). Overall, 183 participants (93.4%) completed the trial, and 13 participants dropped out before the end of the study (6 in the LDBen, 7 in the LDFeb). The reasons cited for discontinuation included voluntarily withdrawal (4 in the LDBen, 5 in the LDFeb), drug discontinuation (1 in the LDBen, 2 in the LDFeb). One participant in the LDBen group stopped the trial because of gout flare at week 4 (Figure 1). Patients in both groups took medication according to the regimen and confirmed by pill counts.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of this study. FEUA=fractional excretion of urate. UUE=uric acid excretion. ALT= alanine aminotransferase, AST=aspartate aminotransferase. eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate. SU = serum urate.

Clinical characteristics at baseline were similar between the two groups (Table 1). Participants receiving “LDBen” or “LDFeb” treatment were of a mean age of 43.89 years and 43.29 years, respectively. The means (SD) duration of gout was similar in the two groups (LDBen 5.2 (4.6) vs. LDFeb 5.6 (4.8) years). More than 75% of study participants had not taken prior urate-lowering therapy. Baseline SU levels were 8.72 (0.73) mg/dL in the LDBen group and 8.59 (0.70) mg/dL in the LDFeb group. Laboratory parameters and coexisting conditions (obesity, hypertension, fatty liver, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease) were similar at baseline between the groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and baseline clinical characteristics.

| LDBen (N=98) | LDFeb (N=98) | |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic and general characteristics | ||

| Age, mean (SD), years | 43.89 (13.10) | 43.29 (12.22) |

| Male, N (%) | 98 (100) | 98 (100) |

| Height, mean (SD), cm | 174.01 (5.84) | 175.37 (5.73) |

| Body weight, mean (SD), kg | 81.07 (9.82) | 82.98 (11.27) |

| Body mass index, mean (SD), kg/m2 | 26.77 (2.85) | 26.97 (3.21) |

| Systolic blood pressure, mean (SD), mmHg | 133.19 (16.23) | 134.18 (15.32) |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mean (SD), mmHg | 84.21 (10.80) | 85.84 (12.09) |

| Gout feature | ||

| Serum urate, median (IQR), mg/dL | 8.70 (7.91, 9.06) | 8.77 (8.10, 9.27) |

| Onset age, mean (SD), years | 39 (12) | 38 (10) |

| Duration of gout, mean (SD), years | 5.2 (4.6) | 5.6 (4.8) |

| Gout flare frequency, N (%) | ||

| < twice / year | 48 (49) | 45 (46) |

| ≥ twice / year | 50 (51) | 53 (54) |

| Tophus, N (%) | 18 (18) | 18 (18) |

| Family history of gout, N (%) | 16 (16) | 21 (21) |

| Naïve of ULT | 75 (77) | 79 (81) |

| Coexisting conditions | ||

| Obesity, N (%) | 40 (41) | 32 (33) |

| Hypertension, N (%) | 16 (16) | 20 (20) |

| Cardiovascular disease, N (%) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Fatty liver, N (%) | 17 (17) | 24 (25) |

| Hyperlipidemia, N (%) | 20 (20) | 17 (17) |

| Diabetes, N (%) | 15 (15) | 14 (14) |

| Blood chemistry parameters | ||

| Serum creatinine, median (IQR), μmol/L | 82 (76, 93) | 85 (76, 95) |

| Fasting blood glucose, mean (SD), mmol/L | 5.52 (0.68) | 5.56 (0.63) |

| Cholesterol, mean (SD), mmol/L | 4.84 (0.82) | 4.76 (1.17) |

| Triglyceride, median (IQR), mmol/L | 1.69 (1.17, 2.34) | 1.67 (1.25, 2.53) |

| AST, median (IQR), U/L | 21 (18, 24.25) | 19 (17, 24) |

| ALT, median (IQR), U/L | 26 (18, 37.5) | 23.5 (16.75, 36) |

| eGFR, mean (SD), ml/min/1.73m2 | 96.30 (15.51) | 94.60 (15.09) |

eGFR=estimated glomerular filtration rate. SD=standard deviation; IQR=interquartile range. LDBen=Low-dose benzbromarone; LDFeb=Low-dose febuxostat. Data were presented as the mean (SD) or median (IQR) or number (N, %).

Efficacy.

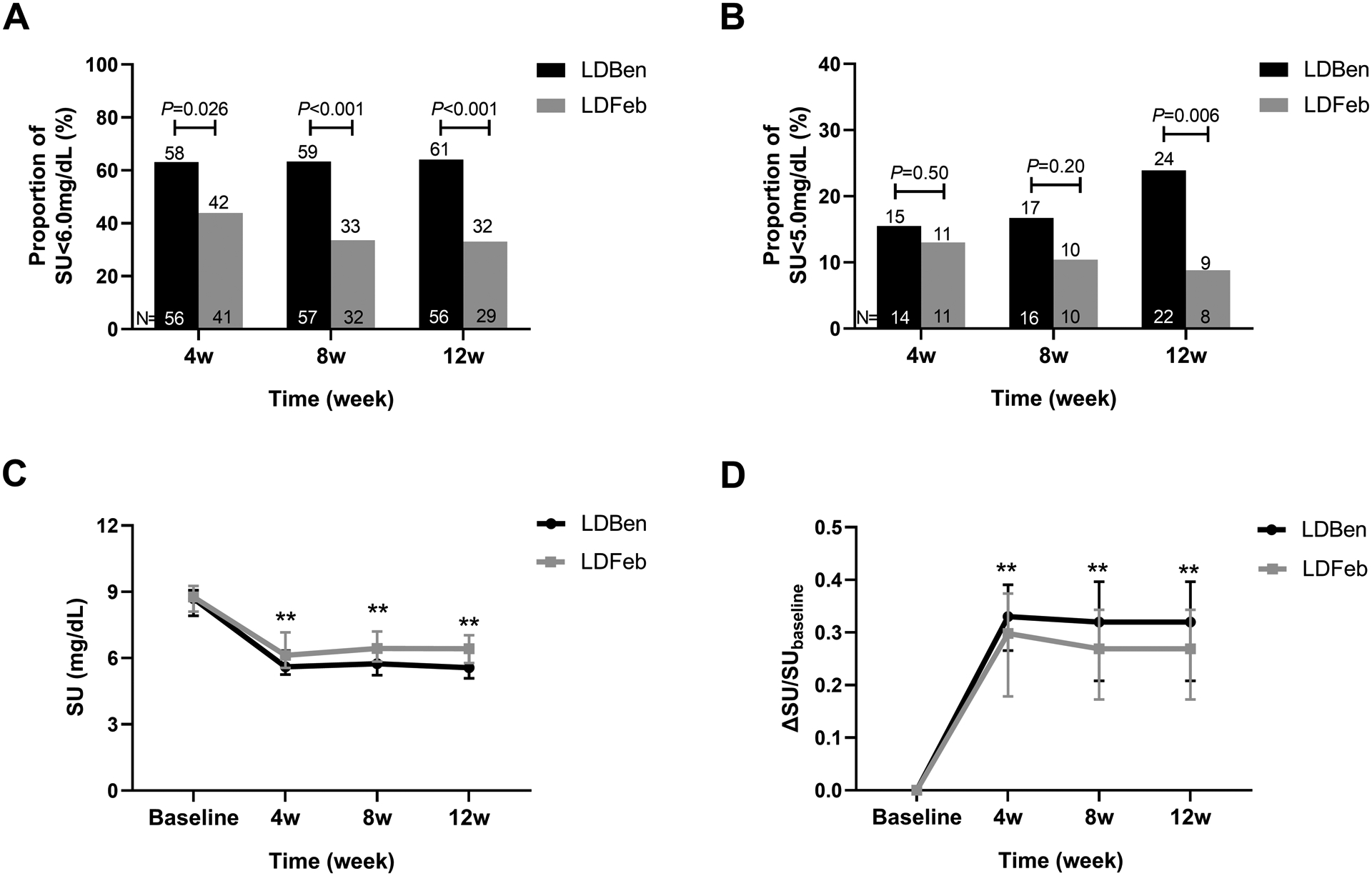

The primary efficacy outcome was the proportion of participants with SU levels <6 mg/dL during the treatment period. The proportion of participants who reached the treatment urate target was significantly higher in the LDBen group than in the LDFeb group at 4 weeks (58% vs. 42%, P=0.03), at 8 weeks (59% vs. 33%, P<0.001), and at 12 weeks (61% vs. 32%, P<0.001) (Figure 2, A).

Figure 2.

The efficacy of the two groups. (A) Proportion of participants with SU < 6.0 mg/dL at weeks 4, 8 and 12. (B) Proportion of participants with SU<5.0 mg/dL at week 4, 8 and 12. (C) The trend of serum urate level of the two groups at 4, 8 and 12 weeks. (D) The ΔSU of the two groups at 4, 8 and 12 weeks. ΔSU= (baseline SU- visit SU)/baseline SU. The data at the bottom of the bar chart shows the number of participants, the data at the top of the bar chart shows the percentage of participants.

The proportion of participants who reached SU <5.0 mg/dL in the two groups was similar at weeks 4 and 8, but more participants in the LDBen group reached this lower SU level after 12 weeks (LDBen 24% vs. LDFeb 9%, P=0.006) (Figure 2, B). The mean SU concentration during the entire study period in the LDBen group was significantly lower than in the LDFeb group (P<0.001). At week 12, the mean (SD) level of SU decreased from 8.59 (0.70) (mg/dL) to 5.81(1.19) (mg/dL) in the LDBen group and from 8.72 (0.73) (mg/dL) to 6.39 (0.94) (mg/dL) in the LDFeb group, respectively (Figure 2, C). The percentage SU change (ΔSU, (baseline SU-visit SU)/baseline SU) was 32.0% in the LDBen group and 26.5% in the LDFeb group (P <0.001) (Figure 2, D).

No differences were detected in glucose and lipid metabolic markers between the two groups at week 12 (Table 2). However, the mean FBG concentration in the LDBen group was significantly lower than in the LDFeb group at week 4, 8 (P<0.001 at both times points) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Major clinical parameters during the trial.

| Baseline | 4 weeks | 8 weeks | 12 weeks | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Numbers of participants completed the follow up, N (%) | ||||

| LDBen | 98 (100) | 97 (99) | 96 (98) | 92 (94) |

| LDFeb | 98 (100) | 98 (100) | 96 (98) | 91 (93) |

| Serum urate, median (IQR), mg/dL | ||||

| LDBen | 8.70 (7.91, 9.06) | 5.60 (5.26, 6.34) **## | 5.74 (5.22, 6.60) **## | 5.57 (5.08, 6.46) **## |

| LDFeb | 8.77 (8.10, 9.27) | 6.12 (5.55, 7.16)## | 6.44 (5.84, 7.21)## | 6.42 (5.77, 7.03)## |

| Fasting blood glucose, mean (SD), mmol/L | ||||

| LDBen | 5.52 (0.68) | 5.35 (0.54)##** | 5.34 (0.44)##** | 5.39 (0.51) |

| LDFeb | 5.56 (0.63) | 5.65 (0.58) | 5.69 (0.59)# | 5.54 (0.58) |

| Cholesterol, mean (SD), mmol/L | ||||

| LDBen | 4.84 (0.82) | 4.80 (0.84) | 4.84 (0.86) | 4.80 (0.85) |

| LDFeb | 4.76 (1.17) | 4.77 (0.99) | 4.83 (0.93) | 4.85 (1.01) |

| Triglyceride, median (IQR), mmol/L | ||||

| LDBen | 1.69 (1.17, 2.34) | 1.57 (1.19, 1.99) | 1.56 (1.14, 2.00)# | 1.50 (1.19, 2.11)# |

| LDFeb | 1.67 (1.25, 2.52) | 1.74 (1.22, 2.67) | 1.65 (1.17, 2.44) | 1.77 (1.17, 2.5) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase, median (IQR), U/L | ||||

| LDBen | 21 (18, 24.25) | 20 (17, 23) #** | 21 (17.25, 23.75) | 20 (16.25, 23) ** |

| LDFeb | 19 (17, 24) | 22 (18, 27)## | 21 (18, 28)## | 22 (18, 28)## |

| Alanine aminotransferase, median (IQR), U/L | ||||

| LDBen | 26 (20, 37.5) | 24 (18, 33)## | 25 (19, 33.75) | 24 (17, 33)##* |

| LDFeb | 23.5 (16.75, 36) | 27 (18, 37)# | 27 (18, 40.75)# | 28 (19, 40) |

| Creatinine, median (IQR), μmol/L | ||||

| LDBen | 82 (76, 93) | 79.5 (72, 88)## | 84 (76, 91) | 81 (75, 89) |

| LDFeb | 85 (76, 95.25) | 81 (74, 90.5)## | 82.5 (75, 90)# | 83 (74, 91) |

| eGFR, mean (SD), ml/min/1.73m 2 | ||||

| LDBen | 96.30 (15.51) | 100.57 (19.96)# | 96.86 (15) | 98.39 (15.42) |

| LDFeb | 94.60 (15.09) | 97.33 (16.71)## | 97.85 (15.58)# | 97.40 (15.87) |

eGFR=estimated glomerular filtration rate, SD=standard deviation; IQR=interquartile range. Data were presented as the mean (±SD) or interquartile range or number (%), LDBen= Low-dose benzbromarone, LDFeb=Low-dose febuxostat. LDBen vs. LDFeb

P< 0.05,

P < 0.01. Baseline vs 4 weeks, 8 weeks, 12 weeks in the LDBen or LDFeb

P< 0.05,

P< 0.01.

Safety.

Over the 12-week study period, the incidences of adverse events (AEs) were similar in two groups: 60% in the LDBen group and 65% in the LDFeb group. There was no serious AEs (Table 3). There was no skin reactions, gastrointestinal adverse events, fulminant hepatitis, or major adverse cardiac events in either group (data not shown). No between-group differences were observed in the proportion of participants with gout flare (LDBen 30% vs. LDFeb 36%, P=0.36) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Percentage of adverse events during the trial.

| LDBen (N=98) | LDFeb (N=98) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Urolithiasis, N (%) | 5 (5) | 2 (2) | 0.25 |

| Gout flare, N (%) | 30 (30) | 36 (36) | 0.36 |

| Once | 18 (18) | 16 (16) | 0.71 |

| Twice | 9 (9) | 14 (14) | 0.27 |

| More than twice | 3 (3) | 6 (6) | 0.50 |

| New-onset AST elevation from normal, N (%) | 1 (1) | 9 (9) | 0.009 |

| 1–2 × elevation | 1 (1) | 8 (8) | 0.035 |

| 2–3 × elevation | 0 | 1 (1) | 1.00 |

| New-onset ALT elevation from normal, N (%) | 4 (4) | 10 (10) | 0.10 |

| 1–2 × elevation | 3 (3) | 8 (8) | 0.12 |

| 2–3 × elevation | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 1.00 |

| eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73m 2 , N (%) | 0 | 0 | 1.00 |

| Other, N (%) | 0 | 0 | 1.00 |

ALT= alanine aminotransferase, AST=aspartate aminotransferase, eGFR=estimated glomerular filtration rate. LDBen= Low-dose benzbromarone, LDFeb=Low-dose febuxostat. Values are N (%).

Liver and kidney function were monitored throughout the trial. An increase from baseline AST was observed at each follow-up in the LDFeb group (P<0.001). In contrast, the AST in the LDBen group did not increase over time, and was lower than the LDFeb group at week 4 and week 12 (P<0.01 at both time points). The percentage of participants with AST elevation in the LDBen group was significantly lower than in the LDFeb group (1% vs. 9%, P=0.02) (Table 3). Furthermore, fewer participants in the LDBen group had AST 2–3 times elevation than in the LDFeb group (1% vs. 8%, P=0.03). The median ALT decreased in the LDBen group, but increased in the LDFeb group at weeks 4 and 8, with lower ALT level in the LDBen group at week 12 compared with LDFeb (P=0.03). Overall, the percentage of participants with transaminase elevation above the upper limit of normal was lower in the LDBen group than in the LDFeb group (4% vs. 15%, P=0.008) (Table 3).

There were no significant differences between the two groups in serum Cr and eGFR during the treatment period (Table 2). No participant developed eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73m2 in either group. Urolithiasis was observed in 5 participants in the LDBen group and 2 participants in the LDFeb group (5% vs. 2%, P=0.25) (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

The findings of this randomized clinical trial provide important new insights into gout management. Specifically, despite advanced understanding of the pathophysiological basis of hyperuricemia and gout, ULT according to the hyperuricemia classification type is not generally recommended and rarely done in Western clinical practice (12, 13, 19). Earlier, observational studies suggested that benzbromarone might be more effective than allopurinol in the reduction of SU in hyperuricemia caused by renal uric acid underexcretion (22). This China-based trial was unique, not only by comparing efficiency and by safety of the benzbromarone and febuxostat in randomized clinical trial participants with gout defined to be of the renal underexcretion type, but also by comparing low dose regimens. Low-dose benzbromarone (25 mg/day) had greater urate-lowering efficacy and an excellent safety profile compared with low-dose febuxostat (20 mg/day) over 12 weeks of therapy. Low-dose benzbromarone produced significantly greater serum urate-lowering treatment success than low-dose febuxostat in the gout patients with renal underexcretion type.

Importantly, the trial was designed to test a hypothesis, by comparing uricosuric to XOI drug ULT in patients with gout with a single dominant cause of hyperuricemia. This design promoted enrollment of a relatively healthy population of younger participants with disease onset particularly common in the 30–40 age group. It is well recognized that the capacity to renally excrete uric acid is modulated partly by the functional capacity for glomerular filtration of urate. In this context, stage 3 CKD, which is very prevalent in gout patients (23, 24), was an exclusion criterion in this study. In addition, this Chinese gout study population had substantially lower prevalence of hypertension, dyslipidemia, and cardiovascular diseases than typical Western gout clinical trial populations (25). Furthermore, all participants were given 1 gram three times daily oral sodium bicarbonate to alkalinize the urine, which likely limited urolithiasis (16), and may have enhanced urate-lowering efficacy (26). Moreover, use of ULT study drugs differed from that in Western clinical trials and typical Western medical practice patterns and recommendations for gout, where allopurinol is the recommended first line ULT drug (12, 13, 27). In this context, FDA approved dosing of febuxostat is for 40 and 80 mg/day, and benzbromarone is not approved in the USA, and is only recommended as a second line ULT drug in Europe, due to potentially lethal hepatotoxicity reactions not believed to be due to modulation of URAT1 activity (31). Furthermore, in countries where benzbromarone remains approved, the starting dosages of benzbromarone range from 12.5mg to 50mg daily (12, 28–30). Hence, as emerging URAT1 inhibitor uricosuric therapies are developed as potential monotherapies in Western clinical trials (27), careful consideration will likely be needed in clinical trial patient selection for pathophysiologic type of hyperuricemia, comorbidities, and use of urinary alkalinization with agents such as potassium citrate (16).

Comparison of results in distinctly designed clinical trials is clearly imperfect. However, in the current low dosing ULT trial in this selective cohort of gout with renal uric acid underexcretion, the percentage of participants achieving serum urate target (<6.0 mg/dL) of 61% in the LDBen group was approximately twice that of LDFeb. By contrast, Naoyuki et al. (31) found that percentage of patients achieving serum urate target (<6.0 mg/dL) was 45.7% in the 20 mg/day febuxostat treatment group. Liang et al. (15) indicated that similar to our results, the rate of achieving the serum urate target was 39.5% in 105 gout patients not selected for primary uric acid underexcretion, using febuxostat 20 mg/day, whereas it was only 35.7% in 109 patients using benzbromarone 25 mg/day.

In this study, the urate-lowering effect of benzbromarone appeared to be more enduring over the trial period than febuxostat. Importantly, febuxostat does lead to a sustained reduction at the final time point compared to baseline. While we did not observed differences in medication adherence using pill counts between groups, it is possible that these differences might be explained by differences in adherence behaviours, differences in the mechanisms of the urate-lowering therapy, FEUA declined as SU levels were reduced by treatment with febuxostat (32), or due to chance. There were no differences in reported medication adherence between the LDBen and LDFeb groups. Some variation in urate levels over time is often observed in ULT trials (15, 33).

Not surprisingly, lack of clinical trial evidence to date has been accompanied by lack of consensus on use of assays for renal uric acid underexcretion in clinical practice for promoting precision in gout management. For example, the 2006 EULAR gout management guidelines recommended that renal uric acid excretion should be determined in selected gout patients, especially those with a family history of young-onset gout, the onset of gout under age 25, or with renal calculi (Strength of recommendation: 72 (95%CI: 62 to 81)) (18). The 2012 ACR Guidelines for Management of Gout recommended that clinicians consider causes of hyperuricemia for gout patients (evidence grade C) (34). However, the most recent update of the ACR Gout Management Guidelines conditionally recommended against checking urinary uric acid to assist in precision of therapy agent choice and strategy in ULT (34, 35).

We did not find severe hepatotoxicity with low-dose benzbromarone, but ethnic background may affect drug responses, and severe hepatotoxicity of benzbromarone has rarely been reported in Asia (11). Notably, elevated transaminases and the rare occurrence of severe liver injury have been reported with febuxostat (14, 36). In our study, the proportion of participants with liver damage in the LDFeb group was higher than that in the LDBen group, mainly in the increase of AST. No significant change in TG was reported in this study, though a previous study suggested that febuxostat could cause elevated triglycerides (15). The incidence of urolithiasis in the LDBen group (5%) was numerically but not significantly higher than that in the LDFeb group (2%) in this study. Incidence of approximately 3% for urolithiasis has been reported with benzbromarone 75–120 mg/day (37, 38), including in a trial in China using benzbromarone 25 mg/day (16), similar to our result.

Several other study limitations should be noted, such as the single center, open-label design and relatively short treatment period, which did not allow assessment of long-term safety. We only included patients with baseline SU level ranging from 8.0 mg/dL to 10 mg/dL, who were relatively young and with few comorbidities, and study results may not be generalizable to patients with higher serum urate levels or impaired kidney function, as well patients from other geographical regions, age and ethnicity groups. The study only recruited men, and the findings may not be generalizable to women with gout. Furthermore, the scope to implement this treatment strategy more widely would be limited currently because the availability of benzbromarone and other uricosurics is varied across the globe and in many countries is very limited. The efficacy of benzbromarone and febuxostat in gout patients with normal excretion was not compared in this study. Last, serum urate-lowering efficacy of both benzbromarone and febuxostat was not maximal at doses of the ULT medication used here.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that low-dose benzbromarone has greater serum urate lowering efficacy than low-dose febuxostat for relatively young and healthy patients with gout of renal underexcretion type. Further investigation would be warranted to test precision in the model for use of a URAT1 inhibitor in selecting first line ULT according to primary renal uric acid underexcretion, as opposed to decreased renal function. However, the results suggest that low dosing of benzbromarone may warrant stronger consideration as a safe and effective therapy to achieve serum urate target in gout without moderate CKD.

Supplementary Material

Funding

This work was sponsored by Shandong Provincial Key Research and Development Plan (Major Scientific and Technological Innovation Project, #2021CXGC011103), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (#31900413, #81770869, #81900636), and Shandong Provincial Science Foundation for Outstanding Youth Scholars (#ZR2021YQ56). RT was supported by the NIH (#AR060772, #AR075990) and the VA Research Service.

Competing interests

Robert Terkeltaub has received research funding from Astra-Zeneca, and has consulted with Horizon, Selecta, SOBI, Dyve BioSciences, Fortress and Astra-Zeneca, Allena, Fortress Bio, and LG Life Sciences. Nicola Dalbeth reports grants and personal fees from Astra-Zeneca, grants from Amgen, personal fees from Dyve BioSciences, personal fees from JW Pharmaceuticals, personal fees from Selecta, personal fees from Arthrosi, personal fees from Horizon, personal fees from Abbvie, personal fees from Janssen, personal fees from PK Med, outside the submitted work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dalbeth N, Gosling AL, Gaffo A, Abhishek A. Gout. Lancet 2021; 397:1843–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dalbeth N, Merriman TR, Stamp LK. Gout. Lancet 2016; 388:2039–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perez-Ruiz F Treating to target: a strategy to cure gout. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009; 48 Suppl 2:ii9–ii14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu X, Zhai T, Ma R, Luo C, Wang H, Liu L. Effects of uric acid-lowering therapy on the progression of chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ren Fail 2018; 40:289–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shoji A, Yamanaka H, Kamatani N. A retrospective study of the relationship between serum urate level and recurrent attacks of gouty arthritis: evidence for reduction of recurrent gouty arthritis with antihyperuricemic therapy. Arthritis Rheum 2004; 51:321–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mandal AK, Mount DB. The molecular physiology of uric acid homeostasis. Annu Rev Physiol 2015; 77:323–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vitart V, Rudan I, Hayward C, Gray NK, Floyd J, Palmer CN, et al. SLC2A9 is a newly identified urate transporter influencing serum urate concentration, urate excretion and gout. Nat Genet 2008; 40:437–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dalbeth N, Merriman T. Crystal ball gazing: new therapeutic targets for hyperuricaemia and gout. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009; 48:222–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ichida K, Matsuo H, Takada T, Nakayama A, Murakami K, Shimizu T, et al. Decreased extra-renal urate excretion is a common cause of hyperuricemia. Nat Commun 2012; 3:764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woodward OM, Kottgen A, Coresh J, Boerwinkle E, Guggino WB, Kottgen M. Identification of a urate transporter, ABCG2, with a common functional polymorphism causing gout. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009; 106:10338–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Azevedo VF, Kos IA, Vargas-Santos AB, da Rocha Castelar Pinheiro G, Dos Santos Paiva E. Benzbromarone in the treatment of gout. Adv Rheumatol 2019; 59:37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.FitzGerald JD, Dalbeth N, Mikuls T, Brignardello-Petersen R, Guyatt G, Abeles AM, et al. 2020 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the Management of Gout. Arthritis Rheumatol 2020; 72:879–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Richette P, Doherty M, Pascual E, Barskova V, Becce F, Castaneda-Sanabria J, et al. 2016 updated EULAR evidence-based recommendations for the management of gout. Ann Rheum Dis 2017; 76:29–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frampton JE. Febuxostat: a review of its use in the treatment of hyperuricaemia in patients with gout. Drugs 2015; 75:427–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liang N, Sun M, Sun R, Xu T, Cui L, Wang C, et al. Baseline urate level and renal function predict outcomes of urate-lowering therapy using low doses of febuxostat and benzbromarone: a prospective, randomized controlled study in a Chinese primary gout cohort. Arthritis Res Ther 2019; 21:200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xue X, Liu Z, Li X, Lu J, Wang C, Wang X, et al. The efficacy and safety of citrate mixture vs sodium bicarbonate on urine alkalization in Chinese primary gout patients with benzbromarone: a prospective, randomized controlled study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2021; 60:2661–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamanaka H, Tamaki S, Ide Y, Kim H, Inoue K, Sugimoto M, et al. Stepwise dose increase of febuxostat is comparable with colchicine prophylaxis for the prevention of gout flares during the initial phase of urate-lowering therapy: results from FORTUNE-1, a prospective, multicentre randomised study. Ann Rheum Dis 2018; 77:270–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang W, Doherty M, Pascual E, Bardin T, Barskova V, Conaghan P, et al. EULAR evidence based recommendations for gout. Part I: Diagnosis. Report of a task force of the Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis 2006; 65:1301–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neogi T, Jansen TL, Dalbeth N, Fransen J, Schumacher HR, Berendsen D, et al. 2015 Gout classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis 2015; 74:1789–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou BF, Cooperative Meta-Analysis Group of the Working Group on Obesity in C. Predictive values of body mass index and waist circumference for risk factors of certain related diseases in Chinese adults--study on optimal cut-off points of body mass index and waist circumference in Chinese adults. Biomed Environ Sci 2002; 15:83–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Consultation WHOE. Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet 2004; 363:157–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perez-Ruiz F, Alonso-Ruiz A, Calabozo M, Herrero-Beites A, Garcia-Erauskin G, Ruiz-Lucea E. Efficacy of allopurinol and benzbromarone for the control of hyperuricaemia. A pathogenic approach to the treatment of primary chronic gout. Ann Rheum Dis 1998; 57:545–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roughley MJ, Belcher J, Mallen CD, Roddy E. Gout and risk of chronic kidney disease and nephrolithiasis: meta-analysis of observational studies. Arthritis Res Ther 2015; 17:90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roughley M, Sultan AA, Clarson L, Muller S, Whittle R, Belcher J, et al. Risk of chronic kidney disease in patients with gout and the impact of urate lowering therapy: a population-based cohort study. Arthritis Res Ther 2018; 20:243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mackenzie IS, Ford I, Nuki G, Hallas J, Hawkey CJ, Webster J, et al. Long-term cardiovascular safety of febuxostat compared with allopurinol in patients with gout (FAST): a multicentre, prospective, randomised, open-label, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2020; 396:1745–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wiederkehr MR, Moe OW. Uric Acid Nephrolithiasis: A Systemic Metabolic Disorder. Clin Rev Bone Miner Metab 2011; 9:207–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Benn CL, Dua P, Gurrell R, Loudon P, Pike A, Storer RI, et al. Physiology of Hyperuricemia and Urate-Lowering Treatments. Front Med (Lausanne) 2018; 5:160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Multidisciplinary Expert Task Force on H, Related D. Chinese Multidisciplinary Expert Consensus on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Hyperuricemia and Related Diseases. Chin Med J (Engl) 2017; 130:2473–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yamanaka H, Japanese Society of G, Nucleic Acid M. Japanese guideline for the management of hyperuricemia and gout: second edition. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids 2011; 30:1018–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yu KH, Chen DY, Chen JH, Chen SY, Chen SM, Cheng TT, et al. Management of gout and hyperuricemia: Multidisciplinary consensus in Taiwan. Int J Rheum Dis 2018; 21:772–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kamatani N, Fujimori S, Hada T, Hosoya T, Kohri K, Nakamura T, et al. An allopurinol-controlled, multicenter, randomized, open-label, parallel between-group, comparative study of febuxostat (TMX-67), a non-purine-selective inhibitor of xanthine oxidase, in patients with hyperuricemia including those with gout in Japan: phase 2 exploratory clinical study. J Clin Rheumatol 2011; 17:S44–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu S, Perez-Ruiz F, Miner JN. Patients with gout differ from healthy subjects in renal response to changes in serum uric acid. Joint Bone Spine 2017; 84:183–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin Y, Chen X, Ding H, Ye P, Gu J, Wang X, et al. Efficacy and safety of a selective URAT1 inhibitor SHR4640 in Chinese subjects with hyperuricaemia: a randomized controlled phase II study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2021; 60:5089–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Khanna D, Fitzgerald JD, Khanna PP, Bae S, Singh MK, Neogi T, et al. 2012 American College of Rheumatology guidelines for management of gout. Part 1: systematic nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapeutic approaches to hyperuricemia. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012; 64:1431–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jansen TL. Rational pharmacotherapy (RPT) in goutology: Define the serum uric acid target & treat-to-target patient cohort and review on urate lowering therapy (ULT) applying synthetic drugs. Joint Bone Spine 2015; 82:225–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bohm M, Vuppalanchi R, Chalasani N, Drug-Induced Liver Injury N. Febuxostat-induced acute liver injury. Hepatology 2016; 63:1047–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Masbernard A, Giudicelli CP. Ten years’ experience with benzbromarone in the management of gout and hyperuricaemia. S Afr Med J 1981; 59:701–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stamp LK, Haslett J, Frampton C, White D, Gardner D, Stebbings S, et al. The safety and efficacy of benzbromarone in gout in Aotearoa New Zealand. Intern Med J 2016; 46:1075–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.