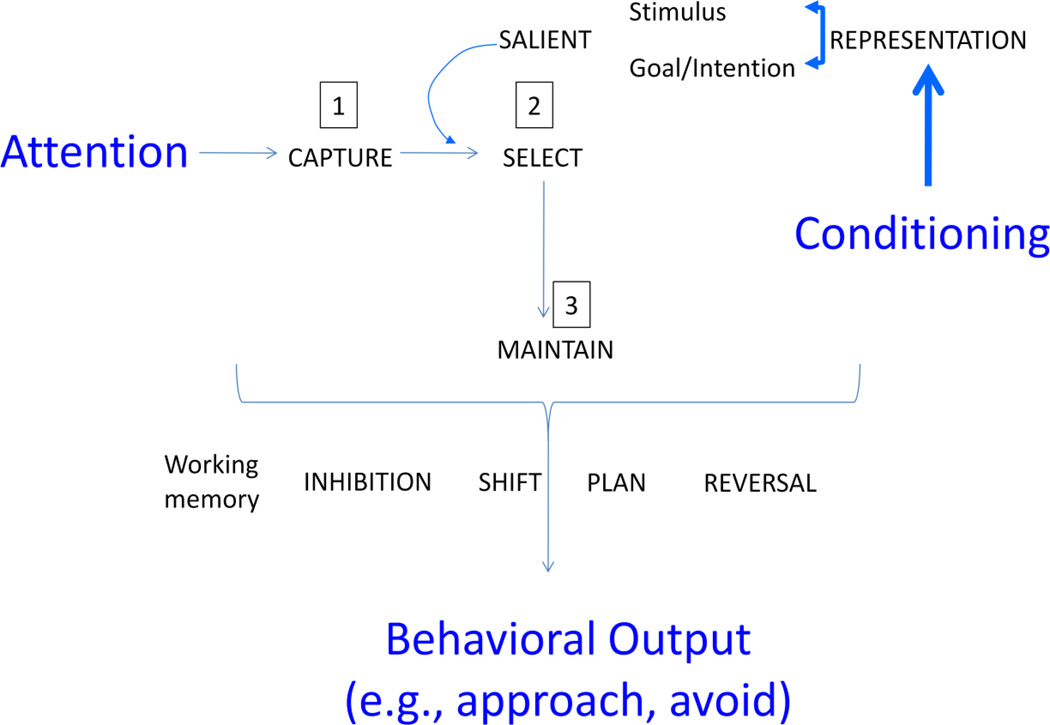

Figure 1. Articulation among attention, conditioning, and motivated behavior.

This schematic describes how attention, conditioning and decision-making are tightly interdependent and significantly contribute to behavioral output.

- First, attention captures the context as a whole (e.g., visual scene of a crowd; hubbub).

-

It then selects a stimulus (e.g., the girl with a red sweater; song in the background). The critical notion here is that attention will select the most salient stimulus. Salience is determined either by the physical features of the stimulus (e.g., color red; favorite song), or by a preset goal or intention (e.g., looking for your friend who has a red coat). Schematically, the selective orienting by physical/perceptual characteristics is mediated by “stimulus-driven attention” mechanisms, whereas the selective orienting by internal rules/intentions is mediated by “goal-driven attention”. Stimuli can be endowed with affective value if they are systematically associated with other affectively-laden stimuli (e.g., song repeatedly heard during summer vacation becomes the favorite song). This is at this juncture that conditioning comes to play a critical role. A neutral stimulus conditioned to threat or to reward will acquire a unique salience that will determine the focus of selective attention.Once attention orients selectively to an object, it maintains the focus on the object to permit, or prime, other cognitive processes to manipulate the information. These cognitive processes pertain mostly to executive function, e.g., working memory, inhibition, shift, plan, reversal, and they ultimately generate a course of action. The course of action is the behavioral output, which can be generalized as an approach or an avoidant response (Ernst et al., 2006).This latter hypothesis requires to be further qualified. The proposed valence bias in associative conditioning may be different for cue- and context-conditioning. Furthermore, the direction of the bias in cue-conditioning may depend on the context in which learning occurs. As a first iteration of this theory, we will make the case for a positive bias, with the understanding that this is only a first approximation awaiting systematic testing.