Abstract

In the absence of overt cellular pathology but profound perceptual disorganization and cognitive deficits, schizophrenia is increasingly considered a disorder of neural coordination. Thus, different causal factors can similarly interrupt the dynamic function of neuronal ensembles and networks, in particular in the prefrontal cortex (PFC), leading to behavioral disorganization. The importance of establishing preclinical biomarkers for this aberrant function has prompted investigations into the nature of psychotomimetic drug effects on PFC neuronal activity. The drugs used in this context include serotonergic hallucinogens, amphetamine, and NMDA receptor antagonists. A prominent line of thinking is that these drugs create psychotomimetic states by similarly disinhibiting the activity of PFC pyramidal neurons. In the present study we did not find evidence in support of this mechanism in PFC subregions of freely moving rats. Whereas the NMDA receptor antagonist MK801 increased PFC population activity, the serotonergic hallucinogen DOI dose-dependently decreased population activity. Amphetamine did not strongly affect this measure. Despite different effects on the direction of change in activity, all three drugs caused similar net disruptions of population activity and modulated gamma oscillations. We also observed reduced correlations between spikerate and LFP power selectively in the gamma band suggesting that these drugs disconnect spike-discharge from PFC gamma oscillators. Gamma band oscillations support cognitive functions affected in schizophrenia. These findings provide insight into mechanisms that may lead to cortical processing deficits in schizophrenia and provide a novel electrophysiological approach for phenotypic characterization of animal models of this disease.

Introduction

Schizophrenia is associated with aberrant information processing in the prefrontal cortex (PFC) (Weinberger et al., 1986; Goldman-Rakic, 1994; Lewis, 1995; Andreasen et al., 1997; Artigas, 2010). The mechanism underlying this disruption is poorly understood. Psychotomimetic drugs are an important modeling tool in this regard because despite acting on distinct groups of receptors, they similarly disrupt behavior. For example, serotonin (5HT) 2A agonists produce hallucinations and sensory disturbances in humans, and hyperlocomotion and cognitive deficits in rodents (Bowers and Freedman, 1966; Vollenweider et al., 1998; Aghajanian and Marek, 2000; Gonzalez-Maeso et al., 2007l; Geyer and Vollenweider, 2008). Likewise, NMDA receptor antagonists and amphetamine produce schizophrenia-like symptoms in humans and aberrant locomotion and cognition in rodents (Snyder, 1976; Krystal et al., 1994). A prominent theory in the field is that, although these drugs act on different receptor and neurotransmitter systems, they all disrupt PFC information processing by disinhibiting pyramidal cells (Aghajanian and Marek, 2000; Lewis and Moghaddam, 2006; Gray and Roth, 2007a, b; Gonzalez-Maeso et al., 2008; Gonzalez-Maeso and Sealfon, 2009).

Application of 5HT2 agonists (and serotonin) to medial PFC slices produces excitatory post-synaptic effects (Aghajanian and Marek, 1997; Marek and Aghajanian, 1999; Zhang and Marek, 2008) and increases discharge of medial PFC neurons projecting to midbrain areas in anesthetized animals (Puig et al., 2003). Likewise, NMDA antagonists increase the activity of PFC neurons (Jackson et al., 2004; Homayoun and Moghaddam, 2008). These findings have had important mechanistic implications for schizophrenia and drug target development (Marek and Aghajanian, 1998a; Moghaddam, 2003; Moghaddam, 2004; Gray and Roth, 2007a; Gonzalez-Maeso et al., 2008; Gonzalez-Maeso and Sealfon, 2009). However, despite evidence of an excitatory role for serotonergic hallucinogens, they inhibit neurons in motor, orbitofrontal (OFC), and anterior cingulate (ACC) cortices of anesthetized animals (Ashby et al., 1989; El Mansari and Blier, 2005). More importantly, their impact on PFC discharge or local field potential (LFP) oscillations in awake animals is unknown. This is critical as the excitatory influence of NMDA receptor antagonists on PFC neurons is observed selectively in awake animals (Jackson et al., 2004; Homayoun and Moghaddam, 2007) but not slice preparations (Wong et al., 1986; Huettner and Bean, 1988).

Here we compared the effects of a serotonergic hallucinogen with other psychotomimetic drugs on PFC neuronal activity of freely moving rats, to determine whether they share a common cellular or network outcome. We measured neuronal activity in OFC and ACC, two regions implicated in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia (Heckers et al., 1998; Kopp and Rist, 1999; Carter et al., 2001; Alain et al., 2002; Weiss et al., 2003; Ragland et al., 2004). Animals were implanted with stationary electrode arrays and received the hallucinogenic 5HT2A/C agonist 1-(2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodophenyl-2-aminopropane) (DOI), NMDA antagonist MK801, and amphetamine in a randomized design. We analyzed neuronal population activity, LFP power, and correlations between spike-discharge and LFP power. We find differential modulation of population activity but similarly reduced network integrity and decoupling of spiking and gamma power. These convergent outcomes are mechanisms by which diverse molecular factors may disrupt cortical function.

Material and Methods

Subjects and Surgical procedure

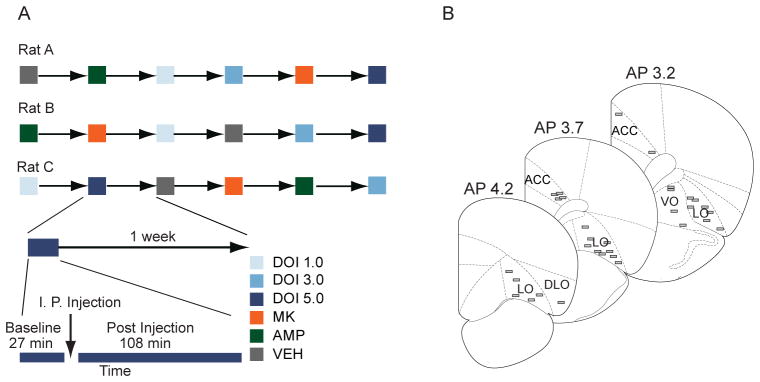

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (approx. 400 g, Harlan, Frederick, MD) were housed on a 12 hour light-dark cycle (lights on at 7 p.m.). Microelectrode arrays were implanted bilaterally in the OFC (n = 11 rats) or in the OFC and contralateral ACC (n = 6 rats) of isoflurane anesthetized rats, and secured with dental cement for chronic recording, as previously reported (Jackson et al., 2004). The following coordinates (Paxinos and Watson, 1998) were utilized (relative to Bregma): ACC = +3.0 mm anterior, +0.5 mm lateral, −2.2 mm ventral from skull; OFC = +3.0 mm anterior, +3.3 mm lateral, −4.5 mm ventral. Recording sessions began after seven days of postoperative recovery. At the completion of all recordings, rats were anesthetized with 400 mg/kg intraperitoneal (i.p.) chloral hydrate and perfused with saline and 10% buffered formalin. Coronal slices of frontal cortex were taken from each brain and cresyl-violet stained. Locations of electrode arrays were confirmed via light microscope. Data from rats with incorrect placements were discarded from all analyses. All procedures were in accordance with the National Institute of Health’s Guide to the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Experimental Design

Neuronal activity was recorded from freely moving rats in a clear polycarbonate home cage with bedding. Rats were habituated to all aspects of the recording process for two days. After a 30 min baseline recording, animals received an i.p. injection of DOI, amphetamine, MK801 or saline vehicle. Neuronal activity was recorded for 120 min after injection. Multiple doses of +/− DOI (1.0, 3.0 and 5.0 mg/kg) were used because this was the first electrophysiology study to examine the effects of this drug in awake PFC. Previous reports have demonstrated that similar doses of DOI produce psychotomimetic effects (Pranzatelli, 1990; Gewirtz and Marek, 2000; Zhang and Marek, 2008). The doses of MK801 (0.1 mg/kg) and amphetamine (2.0 mg/kg) were chosen based on previous studies showing a significant influence on PFC single unit activity and PFC-dependent behaviors (Aultman and Moghaddam, 2001; Homayoun et al., 2004; Jackson et al., 2004; Moghaddam and Homayoun, 2008). Each drug was administered according to a random design with a seven day washout between injections.

Electrophysiology

Single unit activity and LFP were recorded simultaneously via bilateral 8 channel Teflon-insulated stainless steel 50 μm microwire arrays (NB Labs, Denison, TX). Unity-gain junction field effect transistor headstages were attached to a headstage cable and commutator that did not restrict the animal’s movement. Signals were amplified via a multichannel amplifier (Plexon, Dallas, TX). Spikes were band pass filtered between 220 Hz and 5.9 KHz, amplified 500X and digitized at 40 KHz. LFP was band pass filtered between 0.7 Hz and 8 KHz, amplified 1000X, and digitized at 40 KHz. The digitized LFP recording was down sampled to 1 KHz. Single unit activity was then digitally high pass filtered at 300 Hz and LFP were low pass filtered at 125 Hz. Threshold crossing spike waveforms and LFP were stored for offline analysis. Single units were sorted using standard techniques and the Offline Sorter software package (Plexon, Dallas, TX). Single unit activity was only utilized if the neuron displayed a stable waveform throughout the session. Because each animal was allowed one week of washout between recording sessions, we chose to treat units recorded in different sessions as different units despite the fact that the same unit may have been serially recorded. This approach allowed for the most conservative assessment of unit identity. All units meeting these criteria were used in all single unit analyses. We did not remove putative fast-spiking interneurons from our samples as < 3% of neurons met criteria for putative fast-spiking interneurons. Further, there was no correlation between baseline discharge rate and the direction of any drug effect (see results).

Data Analysis

Analysis of single unit data was conducted with Matlab (MathWorks, Natick, MA) and SPSS statistical software (IBM, Somers, NY). The first 3 min of the 30 min baseline were excluded to ensure a stationary baseline. The last 12 min of the post-injection period were excluded to yield a post-injection period 4 times longer than the 27 min baseline period (108 min) (see Figure 1A). For all single unit analyses, 180 sec bins were utilized.

Figure 1.

Experimental design, electrode array placement and baseline activity. (A) Examples of randomized drug delivery schedules, with 1 week washout between test sessions. Each recording session consisted of a drug-free 27 minute baseline, followed by a 108 minute post-injection period. Rats were administered one injection per session. (B) Placement of electrodes in anterior cingulate or orbitofrontal cortices is shown.

Differences in baseline firing rate between samples of units were assessed with Kruskal-Wallis tests. Single unit activity was Z-score normalized against the mean baseline firing rate. In some analyses, normalized activity was absolute value transformed to examine the net change in activity without respect to direction of change. Changes in population activity were assessed by computing the normalized mean baseline and post-injection activity of all units, during the baseline and two 27-min bins following the injection (27 – 54 and 78 – 105 min post-injection). These time periods were chosen because they generally contained stationary population and single unit activity levels. These periods were used for all statistical comparisons, though data from the entire experiment are displayed for clarity. Similar to previous reports, a unit was classified as significantly activated or inhibited if three or more consecutive bins exceeded a 95% confidence interval around the baseline mean (Homayoun et al., 2005; Homayoun and Moghaddam, 2007). The stringency of these criteria were verified by bootstrap analysis of the baseline activity (10,000 samples; expected false-positive rate = 0.002). These criteria for classification were chosen to be sensitive to a wide range of changes in discharge rate, though it should be noted that the majority of drug induced changes in discharge rate were of longer duration. We assessed the cross-correlation in spike-discharge between each pair of simultaneously recorded unit pairs within each region. For this analysis, spike counts were quantified in 10 msec bins, inside a 200 msec window centered on the reference spike. A pair was classified as having a significant response if three consecutive bins of the resulting cross-correlation function exceeded a 99% confidence interval of the expectation under the assumption of a Poisson distribution.

In rats with implants in both OFC and ACC, LFP data were analyzed using customized Chronux (http://www.chronux.org) routines (Mitra and Bokil, 2008). LFP voltage traces were Fourier transformed inside of a sliding time window of 4 sec, with 2 sec steps. A standard multi-taper approach was utilized (Mitra and Pesaran, 1999; McCracken and Grace, 2009) in which 9 tapers were applied to each window. Power spectra were calculated from the multi-tapered Fourier transformations and spectral data in each frequency bin were Z-score normalized against the baseline period and each animal’s data was averaged together to yield group mean spectral data. Each animal’s spectral power during the baseline and two post-injection bins (27 – 54 and 78 – 105 mins post-injection) was used for statistical comparisons. To more accurately describe the modulation of power in the gamma band, we divided gamma into low (30 – 55 Hz) and high (55–80 Hz) gamma bands for all analyses. We assessed the relationship between gamma power and single unit discharge rate with a Pearson correlation. Each unit’s discharge rate and the simultaneously recorded high and low gamma band power were correlated across 9 consecutive 180 sec bins. Each unit’s correlation coefficient was transformed to a Fisher’s Z score. Normalized correlation coefficients were averaged to yield a population mean correlation during the baseline, early post-injection and late post-injection period. While correlations between units are often strongly associated with single unit and gamma power correlations, we did not factor between unit correlations into our calculations.

Statistical testing of LFP power and single unit population data followed the same procedure. Interactions between drug groups and time were assessed with two-way repeated measures ANOVA for both OFC and ACC. One-way between groups ANOVA was utilized to detect differences between each drug group in a given time bin (baseline, early or late post-injection). Post-hoc analyses were done with protected Fisher’s LSD tests. For each drug group, one-way repeated measures ANOVA were utilized to determine if post-injection time points were significantly different from baseline. For all tests, the Greenhouse-Geisser correction was applied as necessary. Statistically significant differences in baseline firing rate between samples were assessed with Kruskal-Wallis tests. Spearman rank-order correlation was used to assess the relationship between post-injection activity and baseline discharge rate. Pearson correlation was used to assess the relationship between dose of DOI and neuronal activity. For single unit data, differences in the distribution of responses (activated, inhibited or no change) between drug and vehicle samples were assessed with a chi-squaretest of independence. A similar procedure was used to assess modulation of the proportion of units with a significant cross correlation. All α levels were set to 0.05.

Results

Distinct effects of DOI, MK801 and amphetamine on unit activity of prefrontal cortex neurons

Drugs were administered in a randomized design (Figure 1A). In total, 527 OFC and 177 ACC units were recorded from histologically verified electrodes (Figure 1B). There was no difference in mean baseline discharge rate before administration of each drug (Table 1). There was no systematic correlation between single unit baseline firing rates and the post-injection effect in any group (Table 2). Each drug evoked sustained changes in the activity of a subpopulation of units, whereas vehicle was associated with weaker and more sporadic changes in activity (Figure 2A–L). In OFC and ACC, a significant interaction between drug group and time was detected (OFC, F(10,1076) = 11.497; ACC, F(10,350) = 7.188; all p < .001). These effects were caused by significant differences between drug groups during the two post-injection bins, but not the baseline period (OFC early bin, F(5,546) = 13.507; OFC late bin, F(5,546) = 11.611; ACC early bin, F(5,180) = 8.740; ACC late bin, F(5,180) = 7.856; all p < .001).

Table 1.

Mean baseline discharge rate. The mean baseline firing rates of each sample of OFC (left) and ACC (right) units, in each recording session. Data are listed as mean and standard error in units of Hz. There were no significant differences between population baseline discharge rates within a region in any sample region (OFC, Kruskal-Wallis χ2(5) = 6.107; ACC, Kruskal-Wallis χ2(5) = 3.635; all p > .05).

| Drug | OFC | ACC |

|---|---|---|

| VEH | 3.87 ± 0.53 | 6.98 ± 1.05 |

| DOI 1.0 | 4.05 ± 0.47 | 5.84 ± 0.87 |

| DOI 3.0 | 4.30 ± 0.51 | 5.38 ± 0.74 |

| DOI 5.0 | 3.82 ± 0.44 | 5.73 ± 1.02 |

| MK | 4.77 ± 0.55 | 6.29 ± 0.89 |

| AMP | 3.87 ± 0.60 | 6.30 ± 0.91 |

Table 2.

Correlation of drug effect and baseline discharge rate. The correlation coefficient of each sample of OFC (left group of columns) and ACC (right group of columns) unit baseline discharge rates and post-injection responses. Data are listed as Spearman correlation coefficients. In each group, left column represents early post-injection bin and right column represents late post-injection bin.

| Drug | OFC | ACC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early | Late | Early | Late | |

| VEH | −0.21 | −0.19 | −0.33 | −0.38 |

| DOI 1.0 | −0.08 | −0.19 | 0.15 | 0.21 |

| DOI 3.0 | −0.02 | −0.20 | −0.26 | −0.38 |

| DOI 5.0 | 0.11 | 0.06 | −0.35 | −0.25 |

| MK | 0.21 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.05 |

| AMP | −0.07 | −0.13 | −0.02 | −0.25 |

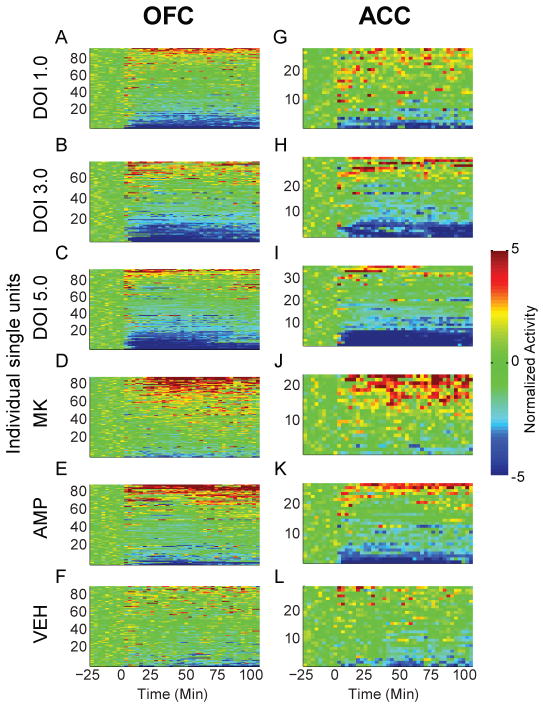

Figure 2.

Modulation of unit activity in OFC and ACC. (A–L) The normalized activity of OFC (A–F) and ACC (G–L) units before and after injection. Baseline activity is normalized to zero, and injection occurred at time = 0. Each row depicts an individual unit and units are sorted by direction and magnitude of change. The administered drug appears to the left of each row of color plots. Color scale for (A–L) appears at right. The total number of units (n) recorded from each rat (N), are listed below for each injection group. DOI 1.0, 3.0, 5.0 mg/kg; OFC: n = 97, 77, 91. N = 12, 11, 12. ACC: n = 27, 33, 36. N = 5, 6, 6. MK801 0.1 mg/kg; OFC: n = 91, N = 12. ACC: n = 24, N = 4. AMP 2.0 mg/kg; OFC: n = 86, N = 12. ACC: n = 27; N = 6. VEH control; OFC: n = 88, N = 11. ACC: n = 30, N = 4. Note that each drug group was associated with both increases and decreases in activity level.

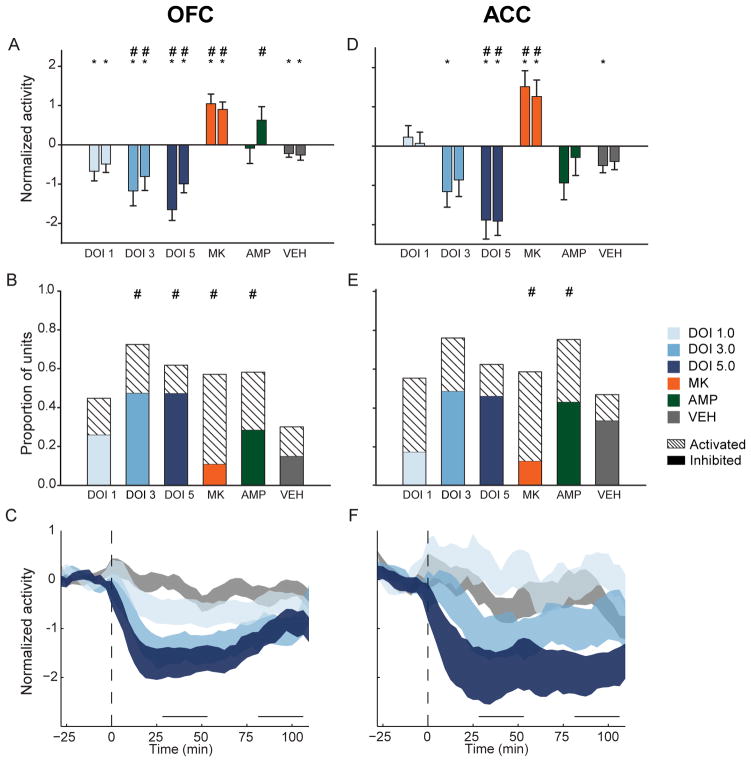

In the OFC, 1.0 mg/kg DOI significantly reduced population activity compared to baseline in both post-injection bins (Figure 3A, F(2,190) = 6.309, p = .008). Larger doses produced greater population suppression compared to baseline (3.0 mg/kg, F(2,156) = 17.618; 5.0 mg/kg, F(2,192) = 28.151; all p < .001) or vehicle (Figure 3A). These effects on population activity were echoed by the effects of DOI on individual units. While 1.0 mg/kg DOI did not strongly affect the activity of many units, larger doses of DOI inhibited the majority of units tested and produced significant differences in the distribution of responses compared to vehicle (Figure 3B, 3.0 mg/kg, χ2(2) = 31.240; 5.0 mg/kg, χ2(2) = 25.582, all p < .001). The higher doses (3.0 and 5.0 mg/kg) produced similar proportions of inhibited neurons (Figure 3B). The effect of DOI on suppressing OFC population activity was consistent throughout the recording session (Figure 3C), and dose was negatively correlated with the early and late post-injection effect (early, r = −.245; late, r = −.145).

Figure 3.

OFC and ACC post-injection population activity. (A) OFC mean normalized population activity from early and late post-injection periods. In each group, left bar represents early and right bar represents late post-injection period. Data are displayed as mean and standard error. Asterisks indicate statistically significant difference compared to drug-free baseline. Number signs (‘#’) indicate statistical significance relative to vehicle control. Legend appears at right, center of figure. (B) Proportion of OFC units in each sample, which were classified as “activated” or “inhibited”. Solid colors indicate inhibited units and dashed bars indicated activated units. Number signs indicate statistical significance compared to vehicle control group. (C) The normalized OFC population activity before and after DOI or vehicle injection are shown. Data are displayed as normalized mean ± standard error (shaded area). Horizontal lines above abscissa indicate “early” and “late” post-injection periods. Injection occurs at time = 0 (dashed vertical line). (D) ACC mean normalized population activity. Format same as A. (E) Proportion of activated or inhibited ACC units in each sample, which were classified as “activated” or “inhibited”. Format same as B. (F) The normalized ACC population activity before and after injection. Format same as C. Legend appears at right, center of figure.

ACC population activity was suppressed by DOI in a similar fashion. Unlike larger doses of DOI, the 1.0 mg/kg dose failed to produce a significant effect on population activity (Figure 3D). Though 1.0 mg/kg produced activation in the majority of units with a significant response, there was no significant difference in the response distribution compared to vehicle (Figure 3E). Larger doses of DOI reduced population activity. In the early post-injection bin 3.0 mg/kg DOI reduced population activity compared to baseline (Figure 3D, F(2,64) = 4.922, p = .010). The 5.0 mg/kg dose reduced ACC population activity at both early and late post-injection bins (Figure 3D, F(2,72) = 16.769, p < .001). Suppression of activity by 3.0 or 5.0 mg/kg occurred in the majority of individual units (Figure 3E). All doses of DOI produced a sustained effect on ACC population activity (Figure 3F). There was a negative correlation between dose of DOI and ACC post-injection effect (early, r = −.307; late, r = −.334).

In contrast to the effects of DOI, MK801 increased population activity in both brain regions (OFC, F(2,180) = 16.89; ACC, F(2,46) = 10.092; all p < .001) during both post-injection periods (Figure 3A, D). The most common change in activity was activation, creating significant differences in the MK801 and vehicle single unit response distributions (Figure 3B, E; OFC, χ2(2) = 19.076, p < .001; ACC, χ2(2) = 7.851, p = .020). Amphetamine increased OFC population activity compared to vehicle only in the late post-injection bin (Figure 3A). Amphetamine non-significantly suppressed ACC population activity (Figure 3D). The lack of strong effects on either population can be explained by the fact that amphetamine simultaneously increased the activity of many single units while decreasing the activity of many others, cancelling out a population effect. In both regions, this resulted in significant differences in the distribution of responses compared to vehicle (Figure 3B, E; OFC, χ2(2) = 15.540, p < .001; ACC, χ2(2) = 6.510, p = .039). Taken together, DOI mediated decreases in population activity that were distinct from those of other psychotomimetic drugs.

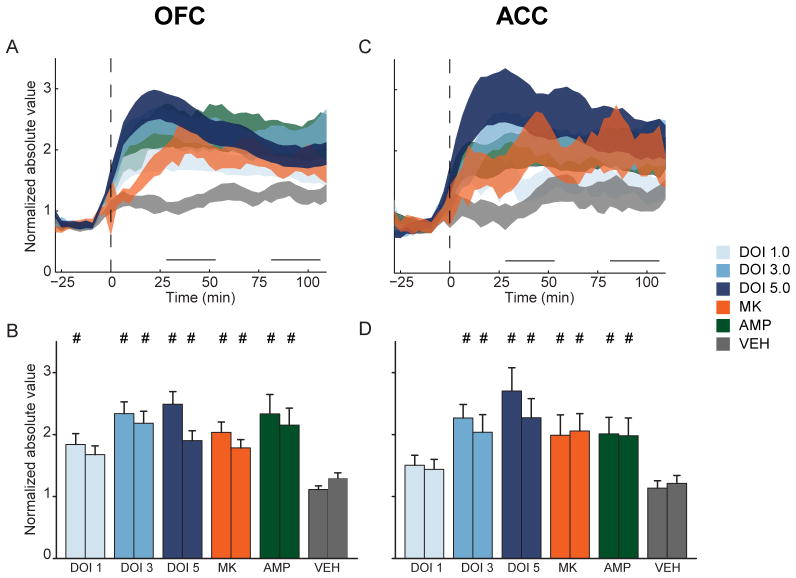

Similar levels of population disruption by DOI, MK801 and amphetamine

Given that each drug drove both increases and decreases in single unit activity and distinctly different patterns of population activity, we reasoned that their psychotomimetic nature may arise, in part, from the net disruption of self-organized activity levels. Each unit’s normalized activity was absolute value transformed to examine disruptions of activity, without respect to the direction of the disruption (Figure 4A–D). In OFC and ACC, a significant interaction between time and drug was detected (OFC, F(10,1082) = 5.064, p < .001; ACC, F(10,350) = 3.093, p = .001). In both regions there were significant differences between drug groups in both post-injection periods (OFC early, F(5, 541) = 6. 604, p < 001; OFC late, F(5,541) = 3.562, p = .004; ACC early, F(5,175) = 4.567, p < .001; ACC late, F(5,175) = 2.610, p = .026).

Figure 4.

Disruption of OFC and ACC population activity. (A) Each OFC unit’s normalized activity was absolute value transformed so that inhibition and activation were represented identically. Absolute value transformed OFC (A) population activity is displayed as mean ± standard error (shaded area). Horizontal lines above abscissa indicate “early” and “late” post-injection periods. Injection occurs at time = 0 (dashed vertical line). (B) Absolute value of mean normalized OFC population activity during early and late post-injection period. In each group, left bar represents early and right bar represents late post-injection period. Data are displayed as mean and standard error. Number signs indicate statistical significance compared to vehicle control. (C) ACC absolute value transformed population activity. Format same as A. (D) ACC absolute value transformed activity during early and late post-injection period. Format same as B. Legend appears at right, center of figure.

In OFC and ACC, DOI dose-dependently elevated absolute value transformed population activity above vehicle levels (Figure 4A–D). In OFC, 1.0 mg/kg DOI produced significant disruptions of population activity only in the early post-injection bin (Figure 4B), while this dose did not produce significant disruptions of activity in the ACC (Figure 4C–D). Larger doses of DOI produced greater levels of population disruption in both periods and both brain regions (Figure 4B, D). In OFC, MK801 and amphetamine also produced increased levels of disruption compared to vehicle during both the early and late post-injection periods (Figure 4B). A similar pattern was detected in ACC (Figure 4D). There was little difference in the magnitude of disruption produced by each psychotomimetic drug. MK801, amphetamine, 3.0 and 5.0 mg/kg DOI all produced equivalent levels of OFC population disruption (Figure 4B). An identical relationship was found in ACC (Figure 4D).

Cross-correlation analysis between each pair of simultaneously recorded units within the OFC or ACC, which is a rough measure of the functional connectivity between units, detected no consistent effect of any psychotomimetic drugs (Table 3). It should be noted that, in both regions, the lowest dose of DOI decreased the proportion of significant pairs compared to baseline (Table 3; OFC early, χ2(1) = 9.133, p = .003; OFC late, χ2(1) = 9.756, p = .002; ACC early, χ2(1) = 14.990, p < .001; ACC late, χ2(1) = 14.990, p < .001). However, this should be interpreted cautiously as the vehicle sessions were characterized by instability in the proportion of pairs that possessed a significant cross correlation (Table 3; OFC early, χ2(1) = 4.701, p = .030; OFC late, χ2(1) = 5.128, p = .024; ACC early, χ2(1) = 16.910, p < .001; ACC late, χ2(1) = 29.212, p < .001).

Table 3.

Proportion of unit-pairs with a significant cross correlation. The proportion of OFC (left group of columns) and ACC (right group of columns) unit-pairs classified as having a significant cross-correlation in discharge are listed in the baseline, early and late post-injection period.

| Drug | OFC | OFC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base | Early | Late | Base | Early | Late | |

| VEH | 0.17 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.17 | 0.38 | 0.45 |

| DOI 1.0 | 0.31 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.30 | 0.12 | 0.12 |

| DOI 3.0 | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.19 |

| DOI 5.0 | 0.23 | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.17 |

| MK | 0.28 | 0.21 | 0.23 | 0.27 | 0.25 | 0.28 |

| AMP | 0.26 | 0.20 | 0.22 | 0.21 | 0.11 | 0.22 |

Effect of DOI, MK801 and amphetamine on LFP oscillations

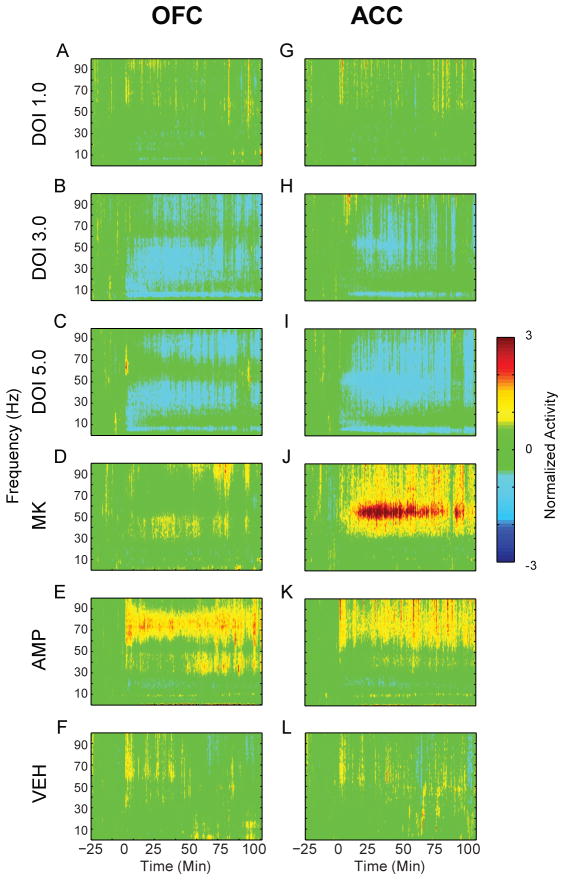

The most consistent effect on LFP oscillations by all drugs was modulation of gamma power (Figure 5A–L). To more accurately describe the results, we divided the gamma band into low and high ranges. In OFC, significant interactions between time and drug were detected in both low (30–55 Hz) and high (55–80 Hz) gamma bands (low gamma, F(10,52) = 7.166; high gamma, F(10, 52) = 4.235; all p < .001). In both cases, these were driven by significant differences between drug groups during both post-injection periods but not the baseline (low gamma early bin, F(5,26) = 7.203; low gamma late bin, F(5,26) = 7.294; high gamma early bin, F(5,26) = 5.254; high gamma late bin, F(5,26) = 6.744; all p < .001). Similarly, in ACC there were significant interactions between time and drug detected in both low and high gamma bands (low gamma, F(10, 40) = 11.999; high gamma, F(10, 40) = 8.240; all p < .001). Both post-injection periods were marked by significant differences between groups (low gamma early bin, F(5,20) = 16.668; low gamma late bin, F(5,20) = 14.896; high gamma early bin, F(5,20) = 9.911; high gamma late bin, F(5,20) = 18.234, all p < .001).

Figure 5.

Modulation of LFP power in OFC and ACC. (A–L) The normalized change in power of LFP oscillations in OFC (A–F) and ACC (G–L) before and after injection. Baseline activity is normalized to zero, and injection occurs at time = 0. The administered drug appears to the left of each row of spectrograms. Color scale appears at right.

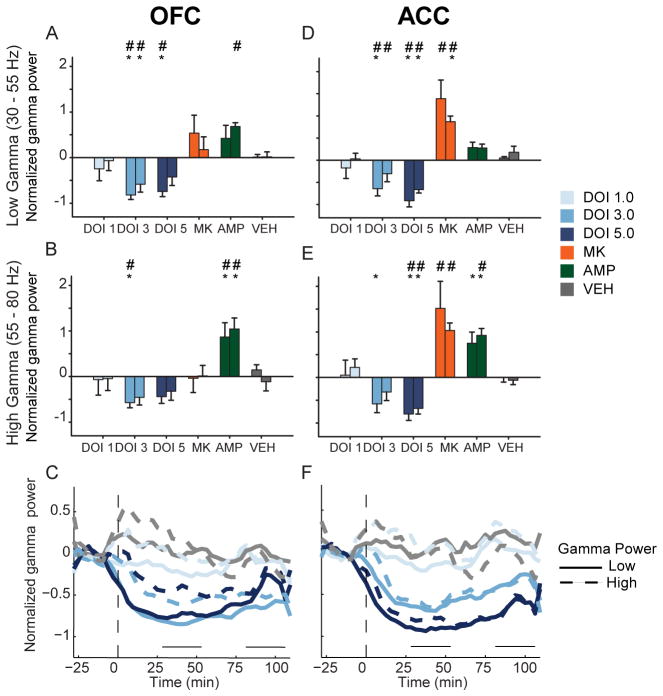

The 3.0 mg/kg dose of DOI decreased OFC low and high gamma power (Figure 6A–B, low gamma, F(2,10) = 18.624, p < .001; high gamma, F(2,10) = 10.479, p = .004). The 5.0 mg/kg dose reduced OFC low gamma (F(2,10) = 13.706, p = .011) but not high gamma power (Figure 6A–B). The effect of DOI was sustained throughout the entire post-injection period in both low and high gamma bands (Figure 6C). A similar trend was found in ACC. The 3.0 mg/kg dose significantly decreased low gamma power (Figure 6D, F(2,8) = 9.832, p = .007). High gamma power was also reduced by 3.0 mg/kg in the early post-injection period (Figure 6E, F(2,8) = 6.208, p = .024). At the 5.0 mg/kg dose of DOI, low and high gamma power were reduced during both post-injection periods (Figure 6D–E, low gamma, F(2,8) = 33.340, p < .001; high gamma, F(2,8) = 16.580, p = .001). In ACC, reductions of gamma power were temporally consistent and dose dependent (Figure 6F).

Figure 6.

Modulation of gamma power in OFC and ACC. (A – B) The normalized change in OFC low (A) and high (B) gamma power (30 – 55 Hz and 55 – 80 Hz, respectively) are depicted as mean and standard error for each group. Left bar represents early and right bar represents late post-injection period. Asterisks indicate statistically significant difference relative to drug-free baseline. Number signs indicate statistical significance compared to vehicle control. (C) Modulation of OFC gamma power by DOI. The normalized mean changes in low and high gamma power are depicted for each dose of DOI in OFC. Solid lines represent low gamma and dashed lines represent high gamma. Horizontal lines above abscissa indicate “early” and “late” post-injection periods. Injection occurs at time = 0 (dashed vertical line). Note that only mean without error is displayed for clarity. Legend appears at right. (D – E) The normalized change in ACC low (D) and high (E) gamma power. Format same as (A – B). Legend appears at right. (F) Modulation of ACC gamma power. Format same as (C).

MK801 strongly increased gamma power in ACC, with less effect in OFC (Figure 6A–B, D–E). There was a modest and non-significant increase in the power of low gamma activity in OFC (Figure 6A–B). ACC gamma power was significantly increased in both low and high gamma bands (Figure 6D–E). Amphetamine increased OFC low gamma power (Figure 6A) and high gamma power (Figure 6B). In ACC, high gamma power was increased more than low gamma power (Figure 6D–E). Thus, in contrast to DOI, both amphetamine and MK801 increased gamma power.

DOI, MK801 and amphetamine reduce coupling of spike-discharge and gamma power

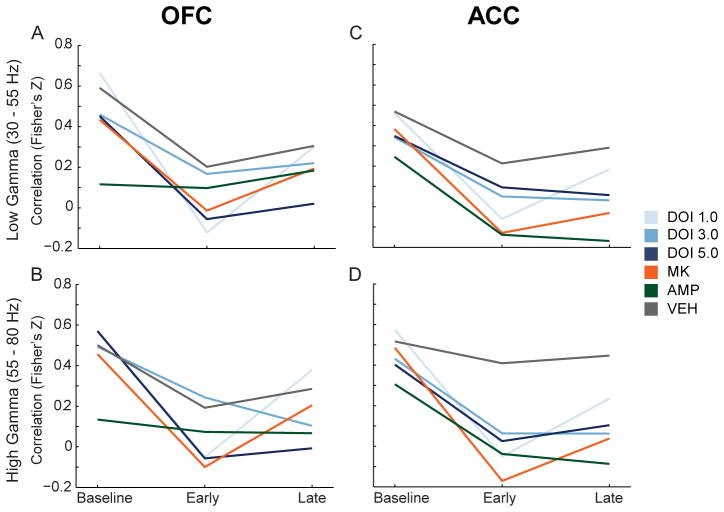

The correlation between changes in gamma power and single unit discharge rate was examined for all treatments in both the low and high gamma bands (Figure 7A–D). We observed that vehicle weakly reduced the correlation between gamma power and discharge rate, while psychotomimetic drugs modulated this correlation more strongly (Figure 7A–D). In OFC, 1.0 and 5.0 mg/kg DOI and MK801 significantly decreased mean correlations between spike-discharge and high gamma power compared to vehicle in the early post-injection period (Figure 7B, F(5,149) = 3.057, p = .012, all post-hoc tests p < .05). DOI at 5.0 mg/kg also decreased the mean correlation in the late post-injection period (F(5,149) = 2.494, p = .034, post-hoc test p < .05). In ACC, more robust differences between vehicle and psychotomimetic drugs were observed. DOI (1.0 mg/kg), MK801 and amphetamine decreased discharge-low gamma power correlation in the early post-injection period (Figure 7C, F(5,183) = 2.954, p = .014, all post-hoc tests p < .05). Each drug, with the exception of the lowest dose of DOI, significantly reduced the ACC discharge-low gamma power correlation compared to vehicle during the late post-injection period (Figure 7C, F(5,183) = 4.193, p = .001, post-hoc test p < .05). All drugs, except the lowest dose of DOI, significantly decreased the ACC discharge-high gamma power correlation compared to vehicle (Figure 7D, early, F(5,183) = 5.706, p < .001; late, F(5,183) = 5.848, p < .001; all post-hoc tests p < .05).

Figure 7.

Modulation of the correlation in gamma power and discharge rate in OFC and ACC. (A – B) The change in correlation between OFC single unit discharge rate and OFC low (A) and high (B) gamma power are depicted as mean Fisher’s Z score normalization of Pearson’s correlation coefficient for each group. The three time points represent baseline, early and late post-injection period. (C – D) The change in correlation between ACC single unit discharge and ACC low (C) and high (D) gamma power. Format same as (A – B). Legend appears at right, center of figure.

Of note, we did not observe consistent changes in the correlation between spike-discharge and spectral power in other frequency bands (data not shown). Furthermore, with our experimental design, we did not observe modulation of spike-field coherence by these drugs at any frequency band in either brain region (data not shown). Taken together, these data indicate that a common detrimental effect of different classes of psychotomimetic drugs in the PFC is to reduce the spontaneous coupling of single unit activity with gamma oscillations.

Discussion

Despite distinct pharmacological profiles, serotonergic hallucinogens, NMDA receptor antagonists and amphetamine are all psychotomimetic in humans, and produce cognitive deficits in humans and laboratory animals. This suggests that these drugs similarly disrupt the function of brain networks that lead to aberrant behaviors related to schizophrenia. Understanding the nature of these network level disruptions may provide insight into mechanisms by which different molecular factors can lead to similar behavioral endpoints. We found that while these drugs had different inhibitory or excitatory effects on OFC and ACC population activity in awake animals, they similarly disrupted net population activity, selectively modulated LFP gamma power, and reduced the correlation of spike rate and gamma power.

Effects on single unit and population activity

The serotonergic hallucinogen DOI dose-dependently inhibited spontaneous population activity of ACC and OFC neurons. In contrast, MK801 increased population activity, and amphetamine activated or suppressed many units, thus weakly influencing population activity. While the impact of amphetamine and MK801 on PFC population activity has been reported before (Jackson et al., 2004; Moghaddam and Homayoun, 2008), this is the first investigation of the effects of serotonergic hallucinogens on cortical neurophysiology in awake animals. The lowest dose of DOI drove weak and sporadic increases in ACC single unit activity, which did not modulate population activity. Higher doses of DOI predominantly decreased the activity of individual ACC units in a sustained fashion. DOI predominantly suppressed OFC single unit activity at all doses. In contrast to MK801 and amphetamine, DOI dose-dependently decreased OFC and ACC population activity.

Our population level findings agree with previous anesthetized recordings, demonstrating reduced neuronal activity in medial PFC (including ACC) and OFC following iontophoresis of DOI (Ashby et al., 1989; Ashby et al., 1990; Rueter et al., 2000). DOI reduces the intrinsic excitability of cortical neurons and activates inhibitory circuits, which could potentially drive these effects (Sheldon and Aghajanian, 1990; Abi-Saab et al., 1999; Zhou and Hablitz, 1999; Carr et al., 2002) but see (Ashby et al., 1990). In contrast to these studies, DOI mediates excitatory post synaptic effects in slice preparations from prelimbic and infralimbic cortices (Aghajanian and Marek, 1997; Marek and Aghajanian, 1998b; Aghajanian and Marek, 1999; Marek and Aghajanian, 1999; Zhang and Marek, 2008). Thus, our results are in agreement with some previous studies, but contrast with others. This difference may be due to differential serotonergic modulation of pyramidal cell activity in PFC subregions. Previous studies reporting excitatory effects have focused mainly on rat prelimbic and infralimbic cortices, whereas inhibitory effects were observed mainly in piriform cortex, OFC and ACC (Ashby et al., 1989; Ashby et al., 1990; Sheldon and Aghajanian, 1990; Aghajanian and Marek, 1997; el Mansari and Blier, 1997; Marek and Aghajanian, 1998b; Aghajanian and Marek, 1999; Marek and Aghajanian, 1999; Rueter et al., 2000; Scruggs et al., 2000; Puig et al., 2003; Scruggs et al., 2003; Muschamp et al., 2004; Zhang and Marek, 2008). Furthermore, recordings in prelimbic and infralimbic cortices have targeted mostly cells in layer V of the PFC whereas our data set was comprised of a more heterogeneous sample of cortical neurons. Previous reports of inhibitory effects from OFC and ACC have sampled across cortical layers as well (Ashby et al., 1989; Ashby et al., 1990; el Mansari and Blier, 1997; Rueter et al., 2000). Collectively, these data suggests that serotonergic hallucinogens do not produce a uniform disinhibitory influence on all PFC subregions and layers. Current theories, which factor in novel mechanisms of antipsychotic drug action, suggest psychotomimetic NMDA receptor antagonists and serotonergic hallucinogens disinhibit the PFC uniformly and through a common mechanism (Aghajanian and Marek, 2000; Gray and Roth, 2007a, b; Gonzalez-Maeso et al., 2008; Gonzalez-Maeso and Sealfon, 2009). However, our data show that MK801 increased discharge in the same networks inhibited by DOI, suggesting that disinhibition theories of psychotomimetic states require reevaluation.

Although each drug had different effects on neuronal population activity, when each unit’s activity was absolute value transformed, equivalently sized disruptions of population activity were observed. The integrity of cortical networks depends on maintaining a delicate balance of inhibitory and excitatory neurotransmission (van Vreeswijk and Sompolinsky, 1996). Thus, excitation or inhibition produced by these drugs at any node in a neuronal network could potentially disrupt the activity of that network, leading to perceptual disorganization and cognitive deficits (London et al., 2010). Along these lines antipsychotic efficacy may be a product of restoring network activity to self-organized levels. In support of this mechanism, antipsychotic drugs normalize both psychotomimetic drug induced increases and decreases in neuronal discharge (Homayoun and Moghaddam, 2008). Collectively these data suggest that the psychotomimetic effect of these drugs may arise, in part, from the decreased integrity of signaling by cortical populations.

Effects on local field potentials

In both OFC and ACC, psychotomimetic drugs modulated the power of gamma oscillations. DOI reduced gamma power, an effect which disrupts spike timing (Fuchs et al., 2007) and may engender a schizophrenia-like state by disrupting the organization of spike-discharge within neuronal networks (Uhlhaas and Singer, 2010). DOI modulated both low and high gamma power, but had a stronger effect on low gamma. On the other hand, the effects of amphetamine were larger in upper gamma band. Low and high gamma bands are pharmacologically dissociable (Oke et al., 2010) and differentially modulate PFC-dependent cognition (Wyart and Tallon-Baudry, 2008; Chaumon et al., 2009). Our data indicate that, while psychotomimetic drugs preferentially disrupt gamma power, these effects are dissociable in terms of the direction of change in gamma power as well as the frequency ranges that are impacted. Gamma oscillations are reflective of local network activity and support working memory, attention and other aspects of human cognition affected in schizophrenia (Traub et al., 2004; Lisman and Buzsaki, 2008; Fries et al., 2007; Fries et al., 2001; Schroeder and Lakatos, 2009; Buzsaki and Draguhn, 2004; Womelsdorf et al., 2006; Uhlhaas and Singer, 2010). Thus, disruption of spontaneous gamma power may be indicative of, or cause, disrupted network signaling and psychotomimetic cognitive impairments.

Spontaneous correlations between spike-rate and gamma power are associated with cognitive processing in humans and non-humans alike (Denker et al.; Liu and Newsome, 2006; Nir et al., 2007). During baseline recordings in freely moving animals, we found a positive correlation between fluctuations in gamma power and neuronal discharge rate. All psychotomimetic drugs decreased this spontaneous correlation relative to vehicle or baseline, most prominently in ACC, despite the fact that they had divergent effects on population activity and gamma power. While a causal link between these correlations and the effects on population activity, gamma power modulation, or behavior has not been established, previous work suggests that both NMDA receptor antagonists and amphetamine decouple PFC gamma oscillators from their controlling networks (Pinault, 2008; Uhlhaas and Singer, 2010). It has also been suggested that decreased correlations between spike-rate and gamma power represent decoupling of a neuron’s spike output from the activity of the population (Nir et al., 2007). Taken together, our data demonstrates that psychotomimetic drugs decouple single unit discharge from rhythmic oscillations in OFC and ACC, and thereby decrease coordination of neuronal populations. This mechanism is in line with our observation that each drug disrupted population activity to a similar degree, suggesting that the net destruction of well-controlled spike-discharge and disconnection from network oscillations may be a shared outcome of these psychotomimetic drugs.

Conclusions

In freely moving animals, the serotonergic hallucinogen DOI reduced population activity and the power of gamma oscillations across both regions of PFC. In contrast, NMDA receptor antagonists increased population activity and gamma power. While each psychotomimetic drug produced diverse effects on the activity of individual neurons, they produced comparable levels of net disruption on population activity and decoupled single unit discharge from gamma oscillations in both PFC subregions. As opposed to disinhibition of PFC populations, disorganization of the spiking and oscillator activity in PFC networks may be common pathways through which distinct molecular factors can lead to disorganized behavior and psychosis. These findings suggest that large scale analysis of cortical activity, such as population disruptions or spike-field interactions, may provide a novel electrophysiological approach to characterize animal models of schizophrenia.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the US National Institute of Health to B.M. (R37 MH48404) and J.W. (T32 NS007433).

Footnotes

We declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abi-Saab WM, Bubser M, Roth RH, Deutch AY. 5-HT2 receptor regulation of extracellular GABA levels in the prefrontal cortex. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;20:92–96. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(98)00046-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aghajanian GK, Marek GJ. Serotonin induces excitatory postsynaptic potentials in apical dendrites of neocortical pyramidal cells. Neuropharmacology. 1997;36:589–599. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(97)00051-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aghajanian GK, Marek GJ. Serotonin, via 5-HT2A receptors, increases EPSCs in layer V pyramidal cells of prefrontal cortex by an asynchronous mode of glutamate release. Brain Research. 1999;825:161–171. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01224-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aghajanian GK, Marek GJ. Serotonin model of schizophrenia: emerging role of glutamate mechanisms. Brain Research. 2000;31:302–312. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(99)00046-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alain C, McNeely HE, He Y, Christensen BK, West R. Neurophysiological evidence of error-monitoring deficits in patients with schizophrenia. Cereb Cortex. 2002;12:840–846. doi: 10.1093/cercor/12.8.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen NC, O’Leary DS, Flaum M, Nopoulos P, Watkins GL, Boles Ponto LL, Hichwa RD. Hypofrontality in schizophrenia: distributed dysfunctional circuits in neuroleptic-naive patients. Lancet. 1997;349:1730–1734. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)08258-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artigas F. The prefrontal cortex: a target for antipsychotic drugs. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2010;121:11–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashby CR, Jr, Edwards E, Harkins K, Wang RY. Effects of (+/−)-DOI on medial prefrontal cortical cells: a microiontophoretic study. Brain Res. 1989;498:393–396. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)91124-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashby CR, Jr, Jiang LH, Kasser RJ, Wang RY. Electrophysiological characterization of 5-hydroxytryptamine2 receptors in the rat medial prefrontal cortex. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1990;252:171–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aultman JM, Moghaddam B. Distinct contributions of glutamate and dopamine receptors to temporal aspects of rodent working memory using a clinically relevant task. Psychopharmacologia. 2001;153:353–364. doi: 10.1007/s002130000590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers MB, Jr, Freedman DX. “Psychedelic” experiences in acute psychosis. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1966:15. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1966.01730150016003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzsaki G, Draguhn A. Neuronal oscillations in cortical networks. Science. 2004;304:1926–1929. doi: 10.1126/science.1099745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr DB, Cooper DC, Ulrich SL, Spruston N, Surmeier DJ. Serotonin receptor activation inhibits sodium current and dendritic excitability in prefrontal cortex via a protein kinase C-dependent mechanism. J Neurosci. 2002;22:6846–6855. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-16-06846.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter CS, MacDonald AW, 3rd, Ross LL, Stenger VA. Anterior cingulate cortex activity and impaired self-monitoring of performance in patients with schizophrenia: an event-related fMRI study. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1423–1428. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.9.1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaumon M, Schwartz D, Tallon-Baudry C. Unconscious learning versus visual perception: dissociable roles for gamma oscillations revealed in MEG. J Cogn Neurosci. 2009;21:2287–2299. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2008.21155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denker M, Roux S, Linden H, Diesmann M, Riehle A, Grun S. The local field potential reflects surplus spike synchrony. Cereb Cortex. 2011;21:2681–2695. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- el Mansari M, Blier P. In vivo electrophysiological characterization of 5-HT receptors in the guinea pig head of caudate nucleus and orbitofrontal cortex. Neuropharmacology. 1997;36:577–588. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(97)00035-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- el Mansari M, Blier P. Responsiveness of 5-HT(1A) and 5-HT2 receptors in the rat orbitofrontal cortex after long-term serotonin reuptake inhibition. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2005;30:268–274. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fries P, Nikolic D, Singer W. The gamma cycle. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30:309–316. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fries P, Reynolds JH, Rorie AE, Desimone R. Modulation of oscillatory neuronal synchronization by selective visual attention. Science. 2001;291:1560–1563. doi: 10.1126/science.1055465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs EC, Zivkovic AR, Cunningham MO, Middleton S, Lebeau FE, Bannerman DM, Rozov A, Whittington MA, Traub RD, Rawlins JN, Monyer H. Recruitment of parvalbumin-positive interneurons determines hippocampal function and associated behavior. Neuron. 2007;53:591–604. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gewirtz JC, Marek GJ. Behavioral evidence for interactions between a hallucinogenic drug and group II metabotropic glutamate receptors. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;23:569–576. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00136-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geyer MA, Vollenweider FX. Serotonin research: contributions to understanding psychoses. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2008;29:445–453. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2008.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman-Rakic P. Working memory dysfunction in schizophrenia. Journal of Neuropsychiatry & Clinical Neuroscience. 1994;6:348–357. doi: 10.1176/jnp.6.4.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Maeso J, Sealfon SC. Psychedelics and schizophrenia. Trends Neurosci. 2009;32:225–232. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Maeso J, Weisstaub NV, Zhou M, Chan P, Ivic L, Ang R, Lira A, Bradley-Moore M, Ge Y, Zhou Q, Sealfon SC, Gingrich JA. Hallucinogens recruit specific cortical 5-HT(2A) receptor-mediated signaling pathways to affect behavior. Neuron. 2007;53:439–452. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Maeso J, Ang RL, Yuen T, Chan P, Weisstaub NV, Lopez-Gimenez JF, Zhou M, Okawa Y, Callado LF, Milligan G, Gingrich JA, Filizola M, Meana JJ, Sealfon SC. Identification of a serotonin/glutamate receptor complex implicated in psychosis. Nature. 2008;452:93–97. doi: 10.1038/nature06612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray JA, Roth BL. Molecular targets for treating cognitive dysfunction in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2007a;33:1100–1119. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray JA, Roth BL. The pipeline and future of drug development in schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2007b;12:904–922. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halberstadt AL, van der Heijden I, Ruderman MA, Risbrough VB, Gingrich JA, Geyer MA, Powell SB. 5-HT(2A) and 5-HT(2C) receptors exert opposing effects on locomotor activity in mice. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:1958–1967. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckers S, Rauch S, Goff D, Savage C, Schacter D, Fischman A, Alpert N. Impaired recruitment of the hippocampus during conscious recollection in schizophrenia. Nature Neuroscience. 1998;1:318–323. doi: 10.1038/1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homayoun H, Moghaddam B. NMDA receptor hypofunction produces opposite effects on prefrontal cortex interneurons and pyramidal neurons. J Neurosci. 2007;27:11496–11500. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2213-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homayoun H, Moghaddam B. Orbitofrontal cortex neurons as a common target for classic and glutamatergic antipsychotic drugs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:18041–18046. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806669105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homayoun H, Jackson ME, Moghaddam B. Activation of metabotropic glutamate 2/3 receptors reverses the effects of NMDA receptor hypofunction on prefrontal cortex unit activity in awake rats. J Neurophysiol. 2005;93:1989–2001. doi: 10.1152/jn.00875.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homayoun H, Stefani MR, Adams BW, Tamagan GD, Moghaddam B. Functional Interaction Between NMDA and mGlu5 Receptors: Effects on Working Memory, Instrumental Learning, Motor Behaviors, and Dopamine Release. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:1259–1269. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huettner JE, Bean BP. Block of N-methyl-D-aspartate-activated current by the anticonvulsant MK-801: selective binding to open channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:1307–1311. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.4.1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson M, Homayoun H, Moghaddam B. NMDA receptor hypofunction produces concomitant firing rate potentiation and burst activity reduction in the prefrontal cortex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of U S A. 2004;101:6391–6396. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308455101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopp B, Rist F. An event-related brain potential substrate of disturbed response monitoring in paranoid schizophrenic patients. J Abnorm Psychol. 1999;108:337–346. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.108.2.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krystal JH, Karper LP, Seibyl JP, Freeman GK, Delaney R, Bremner JD, Heninger GR, Bowers MB, Jr, Charney DS. Subanesthetic effects of the noncompetitive NMDA antagonist, ketamine, in humans. Psychotomimetic, perceptual, cognitive, and neuroendocrine responses. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:199–214. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950030035004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis DA. Neural circuitry of the prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia [comment] Archives of General Psychiatry. 1995;52:269–273. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950160019004. discussion 277–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis DA, Moghaddam B. Cognitive dysfunction in schizophrenia: convergence of gamma-aminobutyric acid and glutamate alterations. Arch Neurol. 2006;63:1372–1376. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.10.1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisman J, Buzsaki G. A neural coding scheme formed by the combined function of gamma and theta oscillations. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34:974–980. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Newsome WT. Local field potential in cortical area MT: stimulus tuning and behavioral correlations. J Neurosci. 2006;26:7779–7790. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5052-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- London M, Roth A, Beeren L, Hausser M, Latham PE. Sensitivity to perturbations in vivo implies high noise and suggests rate coding in cortex. Nature. 2010;466:123–127. doi: 10.1038/nature09086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loscher W, Annies R, Honack D. The N-methyl-D-Aspartate receptor antagonist MK-801 induces increases in dopamine and serotonin metabolism in several brain regions of rats. Neuroscience Letters. 1991;128:191–194. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(91)90258-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marek G, Aghajanian G. The electrophysiology of prefrontal serotonin systems: Therapeutic implications for mood and psychosis. Biological Psychiatry. 1998a;44:1118–1127. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00036-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marek GJ, Aghajanian GK. 5-Hydroxytryptamine-induced excitatory postsynaptic currents in neocortical layer V pyramidal cells: suppression by mu-opiate receptor activation. Neuroscience. 1998b;86:485–497. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00043-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marek GJ, Aghajanian GK. 5-HT2A receptor or alpha1-adrenoceptor activation induces excitatory postsynaptic currents in layer V pyramidal cells of the medial prefrontal cortex. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1999;367:197–206. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00945-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCracken CB, Grace AA. Nucleus accumbens deep brain stimulation produces region-specific alterations in local field potential oscillations and evoked responses in vivo. J Neurosci. 2009;29:5354–5363. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0131-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitra P, Bokil H. Observed brain dynamics. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mitra PP, Pesaran B. Analysis of dynamic brain imaging data. Biophys J. 1999;76:691–708. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77236-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moghaddam B. Bringing order to the glutamate chaos in schizophrenia. Neuron. 2003;40:881–884. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00757-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moghaddam B. Targeting metabotropic glutamate receptors for treatment of the cognitive symptoms of schizophrenia. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004;174:39–44. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-1792-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moghaddam B, Adams BW. Reversal of phencyclidine effects by a group II metabotropic glutamate receptor agonist in rats. Science. 1998;281:1349–1352. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moghaddam B, Homayoun H. Divergent plasticity of prefrontal cortex networks. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:42–55. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muschamp JW, Regina MJ, Hull EM, Winter JC, Rabin RA. Lysergic acid diethylamide and [−]-2,5-dimethoxy-4-methylamphetamine increase extracellular glutamate in rat prefrontal cortex. Brain Res. 2004;1023:134–140. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nir Y, Fisch L, Mukamel R, Gelbard-Sagiv H, Arieli A, Fried I, Malach R. Coupling between neuronal firing rate, gamma LFP, and BOLD fMRI is related to interneuronal correlations. Curr Biol. 2007;17:1275–1285. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.06.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oke OO, Magony A, Anver H, Ward PD, Jiruska P, Jefferys JG, Vreugdenhil M. High-frequency gamma oscillations coexist with low-frequency gamma oscillations in the rat visual cortex in vitro. Eur J Neurosci. 2010;31:1435–1445. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07171.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. San Diego: Academic Press; 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinault D. N-methyl d-aspartate receptor antagonists ketamine and MK-801 induce wake-related aberrant gamma oscillations in the rat neocortex. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63:730–735. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pranzatelli MR. Evidence for involvement of 5-HT2 and 5-HT1C receptors in the behavioral effects of the 5-HT agonist 1-(2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodophenyl aminopropane)-2 (DOI) Neurosci Lett. 1990;115:74–80. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(90)90520-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puig MV, Celada P, Diaz-Mataix L, Artigas F. In vivo modulation of the activity of pyramidal neurons in the rat medial prefrontal cortex by 5-HT2A receptors: relationship to thalamocortical afferents. Cereb Cortex. 2003;13:870–882. doi: 10.1093/cercor/13.8.870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragland JD, Gur RC, Valdez J, Turetsky BI, Elliott M, Kohler C, Siegel S, Kanes S, Gur RE. Event-related fMRI of frontotemporal activity during word encoding and recognition in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1004–1015. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.6.1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rueter LE, Tecott LH, Blier P. In vivo electrophysiological examination of 5-HT2 responses in 5-HT2C receptor mutant mice. Naunyn-Schmiedebergs Archives of Pharmacology. 2000;361:484–491. doi: 10.1007/s002109900181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder CE, Lakatos P. The gamma oscillation: master or slave? Brain Topogr. 2009;22:24–26. doi: 10.1007/s10548-009-0080-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scruggs JL, Schmidt D, Deutch AY. The hallucinogen 1-[2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodophenyl]-2-aminopropane (DOI) increases cortical extracellular glutamate levels in rats. Neurosci Lett. 2003;346:137–140. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(03)00547-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scruggs JL, Patel S, Bubser M, Deutch AY. DOI-Induced activation of the cortex: dependence on 5-HT2A heteroceptors on thalamocortical glutamatergic neurons. Journal of Neuroscience (Online) 2000;20:8846–8852. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-23-08846.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiden LS, Sabol KE, Ricaurte GA. Amphetamine: effects on catecholamine systems and behavior. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1993;33:639–677. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.33.040193.003231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon PW, Aghajanian GK. Serotonin (5-HT) induces IPSPs in pyramidal layer cells of rat piriform cortex: evidence for the involvement of a 5-HT2-activated interneuron. Brain Res. 1990;506:62–69. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)91199-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder SH. The dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia: focus on the dopamine receptor. Am J Psychiatry. 1976;133:197–202. doi: 10.1176/ajp.133.2.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traub RD, Bibbig A, LeBeau FE, Buhl EH, Whittington MA. Cellular mechanisms of neuronal population oscillations in the hippocampus in vitro. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2004;27:247–278. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tricklebank MD, Singh L, Oles RJ, Preston C, Iversen SD. The behavioural effects of MK-801: a comparison with antagonists acting non-competitively and competitively at the NMDA receptor. Eur J Pharmacol. 1989;167:127–135. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(89)90754-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlhaas PJ, Singer W. Abnormal neural oscillations and synchrony in schizophrenia. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11:100–113. doi: 10.1038/nrn2774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Vreeswijk C, Sompolinsky H. Chaos in neuronal networks with balanced excitatory and inhibitory activity. Science. 1996;274:1724–1726. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollenweider FX, Vollenweider-Scherpenhuyzen MF, Babler A, Vogel H, Hell D. Psilocybin induces schizophrenia-like psychosis in humans via a serotonin-2 agonist action. Neuroreport. 1998;9:3897–3902. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199812010-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger D, Berman K, Zec R. Physiological dysfunction of dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia. I. Regional cerebral blood flow (rCBF) evidence. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1986;43:114–125. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800020020004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss AP, Schacter DL, Goff DC, Rauch SL, Alpert NM, Fischman AJ, Heckers S. Impaired hippocampal recruitment during normal modulation of memory performance in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53:48–55. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01541-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Womelsdorf T, Fries P, Mitra PP, Desimone R. Gamma-band synchronization in visual cortex predicts speed of change detection. Nature. 2006;439:733–736. doi: 10.1038/nature04258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong EH, Kemp JA, Priestley T, Knight AR, Woodruff GN, Iversen LL. The anticonvulsant MK-801 is a potent N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:7104–7108. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.18.7104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyart V, Tallon-Baudry C. Neural dissociation between visual awareness and spatial attention. J Neurosci. 2008;28:2667–2679. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4748-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Marek GJ. AMPA receptor involvement in 5-hydroxytryptamine2A receptor-mediated pre-frontal cortical excitatory synaptic currents and DOI-induced head shakes. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2008;32:62–71. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2007.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou FM, Hablitz JJ. Activation of serotonin receptors modulates synaptic transmission in rat cerebral cortex. J Neurophysiol. 1999;82:2989–2999. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.6.2989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]