Abstract

Complex systems approaches have received increasing attention in public health because reductionist approaches yield limited insights in the context of dynamic systems. Most discussions to date have been highly abstract. There is a need to consider the application of complex systems approaches to specific research questions. After briefly reviewing the features of population health problems for which complex systems approaches are most likely to yield new insights, this commentary discusses possible applications of complex systems to health disparities research. It provides illustrative examples of how complex systems approaches may help address unanswered and persistent questions regarding genetic factors, life course processes, place effects, and the impact of upstream policies. It is argued that the concepts and methods of complex systems may help researchers move beyond current impasse points in health disparities research.

Researchers in public health have periodically reiterated calls for approaches that recognize that individual and population health emerge from the functioning of systems. (1–16) Resurgence of interest in systems approaches has been stimulated by growing application of systems approaches to study biological (17–19) and social processes(20, 21) and by increasing frustration with the ability of traditional methods to provide satisfying explanations or solutions for persistent health problems such as inequalities in health.

Systems approaches have historically emphasized the need to understand dynamic interrelations between various components. (22) Because the effect of a given input depends on other conditions in the system, emphasis shifts from isolating the “causal” effect of a single factor to comprehending the functioning of the system as a whole. Complex systems typically include heterogeneous agents at various levels, contact structures between agents, adaptation, non-linear dynamics, and stochasticity. These features lead to the emergence of patterns at various scales. (9, 23)

The recognition that the health of individuals and populations is the manifestation of a system in which biology interacts with environments and individuals interact with each other and with environments over time is a key element of the concept of population health. However, the specific ways in which features of this system give rise to health are rarely made explicit. Systems approaches encourage investigators, indeed require them, to make these relations explicit. Articulating these relations in detail may also help develop theory in population health that goes beyond artificial distinctions like “causes of disease in individuals” and “causes of disease in populations”. This is because from a systems perspective health is conceptualized as an emergent property of a system, in which processes operating at the levels of individuals and populations are inextricably connected.

A particularly vexing problem in population health is that of health disparities (24) Health disparities are characterized by persistent questions about etiology and policy. These questions may have remained difficult to answer in part because they involve the types of dynamic processes that characterize systems and because most existing work has been based on approaches that largely ignore these dynamics. Systems thinking and systems methodologies may help researchers move beyond current stalemates and enhance the production of knowledge regarding the causes of health disparities as well as the identification of effective policies or interventions.

When are complex systems approaches likely to make the most difference?

A key characteristic of the types of population health problems for which complex systems approaches may be useful is the presence of influential positive or negative feedback loops. (25, 26) Examples of feedback mechanisms include feedbacks between behavioral and environmental features (healthy food availability promoting a healthier diet which in turn creates greater demand for healthy foods) and feedbacks between health and social circumstances (health affecting income and income affecting health). Feedbacks are not always reinforcing or positive. The presence of negative or balancing feedbacks can regulate a system’s behavior so that it maintains stability or equilibrium over time. For example, balancing feedbacks may operate at the latter stages of an epidemic to slow the development of new cases. Due partly to the inadequacy of traditional quantitative methods in accounting for feedback loops, feedbacks are generally assumed to be ignorable in most public health research. Yet their presence can give rise to non-linear effects, effects distant in space and time, unanticipated effects, large effects of small changes in initial conditions, and outcomes that are strongly dependent on the history and order of past events, (6, 10, 27) all features of population health problems.

Another characteristic of population health problems especially suited to complex systems approaches is the presence of dependencies between individuals, i.e. situations in which the outcome for one individual is affected by the outcomes in other individuals. For this reason, infectious disease epidemiology has been at the forefront of the application of these methods in population health.(28) Non-infectious disease related outcomes such as behaviors may share some of these features. (29) This contagiousness generates feedback mechanisms through which individual and group characteristics affect each other over time. Accounting for the processes that generate these dependencies is important to correctly estimating the impact of an intervention on disease rates. This is distinct from for non-independence or interference between units as a nuisance that complicates causal inference or needs to be accounted for statistically.

A third characteristic is the presence of macro-level patterns that emerge for the interplay of factors at different levels of organization. In population health, interest often centers in understanding the factors that lead to differences in rates of disease across groups. But these macro level patterns are the end result of a multiplicity of processes operating at different levels and scales (e.g. cellular/molecular, organism, inter-individual, and macro environmental). Complex systems approaches can help us explicitly understand how lower-level processes “scale-up” and interact with higher level factors to generate the higher scale macro patterns that we observe.(30)

Although feedbacks, dependencies, and emergent patterns may characterize virtually all population health problems, they may be especially important in health disparities. The systems nature of health disparities may explain their persistence and robustness across different health outcomes and over time, and their resistance to interventions. The following section reviews some key outstanding questions in health disparities research and uses simple schematic examples to illustrate how systems thinking may help us conceptualize these problems differently.

Health disparities questions

What role do genes really play?

Despite numerous discussions of the roles of genes and environments in health disparities (31–36) there remains considerable uncertainty regarding the importance of genetic variation. It has long been clear that there is substantially less genetic variation between than within commonly defined race/ethnic groups.(37) It is also true that certain genetic markers tend to cluster by geographic ancestry (38, 39) and although these constitute only a very small proportion of total genetic variation, their presence suggests that genetic differences across these groups could plausibly have at least some implications for health differences. On the other hand, the presence of disparities in multiple unrelated health outcomes as well as the presence of heterogeneity in race/ethnic differences over time and across contexts suggests that genetic factors alone are a very unlikely explanation for the bulk of health disparities. Moreover the failure of genetic variation to explain a substantial proportion of variation in disease risk for common chronic diseases even in cases where genetic polymorphisms linked to disease have been consistently identified suggests that gene-gene interactions and gene-environment interactions are likely to play a major role.(40)

A more nuanced understanding of how genes interact dynamically with each other and with environments is necessary to fully understand if and how genetic variation contributes to health disparities.(41) (42) Yet the methods commonly used are limited in their ability to capture the dynamic processes linking genes and environments over time. The reliance on statistical methods that ignore these dynamics may have contributed to the current stalemate in which neither genetic nor environmental factors appear to convincingly explain health disparities in ways that are compelling to both social and biological scientists.

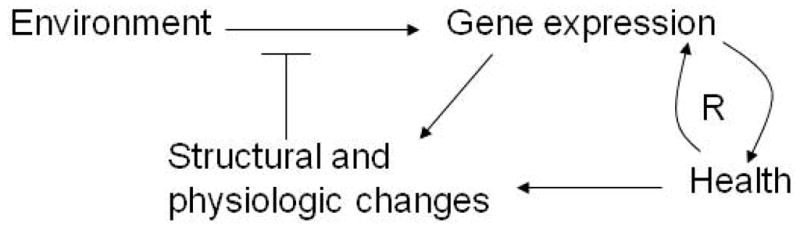

One example of the dynamic relations of genes and environments is Cole’s theory of “recursive developmental remodeling”. (43) Under this theory, environmental conditions affect gene expression triggering sets of neuroendocrine responses which in turn affect biological structure and function. These changes in biological structure and function in turn modulate the subsequent effects of the environment on gene expression. This creates a reinforcing mechanism by which the effects of the environment on gene expression can be enhanced or dampened substantially over time (figure 1). Health status itself may be affected by, and also affect gene expression, further reinforcing the cycle. The impact of environments or the role of genetic factors that modulate environmental influences on gene expression cannot be properly understood without accounting for these dynamic relations.

Figure 1.

The interplay of genes and environments: recursive developmental remodeling (adapted from Cole 2009)(43)

The figures utilize a simple notation in which a single headed arrow for X to Y indicates that X is a cause of Y (e.g. family norms are causally related to physical activity) or that X causes increased exposure to Y (e.g. genetic factors related to exercise predisposition affect selection into exercise promoting environments). A line intersecting a one headed arrow (in the form of a T) indicates that the factor modifies or modulates the relation between X and Y (effect modification in epidemiologic terms). For example in Figure 1 the T-shaped line from structural/physiologic changes that intersects the arrow from environment to gene expression indicates that the structural and physiologic changes modify or modulate the effect of environments on gene expression. Analogously, in figure 5 discrimination modifies the relation between personal resources/preferences and residential location; and stress modifies the relation between location of services and behaviors. Classic positive or negative feedback loops are indicated with an R (reinforcing) or a B (balancing). Reinforcing loops promote or reinforce change in one direction. Balancing loops tend to close the gap between the current state and the desired state (e.g. increases in stress result in health behaviors which reduce stress levels bringing the body back into its desired state). See text for explanation of specific R and B loops. In order to keep figures simple and because variables are not always quantitative, directionality (plus or minus signs associated with the arrows) is not indicated in the figures but the types of relations can be inferred from the description in the text.

The dynamics are rendered even more complex if we recognize that in addition to interacting with environments, genes may also be related to the extent to which persons are exposed to certain types of social and environmental contexts. These contexts may affect health directly or may modulate the effects of genes.(44) A simple example is that genes have consequences for skin color and in certain social contexts, skin color may be correlated with exposure to discrimination(45) because persons are discriminated partly based on their skin color. The cause of the discrimination is the social norm, but skin color determines who is discriminated. This exposure to discrimination may in turn have health implications directly through stress mechanisms, through effects on gene expression (triggering the processes shown in figure 1), or through interactions with hypertension-related genetic variants that covary with skin color. Failure to understand these relations would result in overestimates of the associations between genes linked to skin color and hypertension.

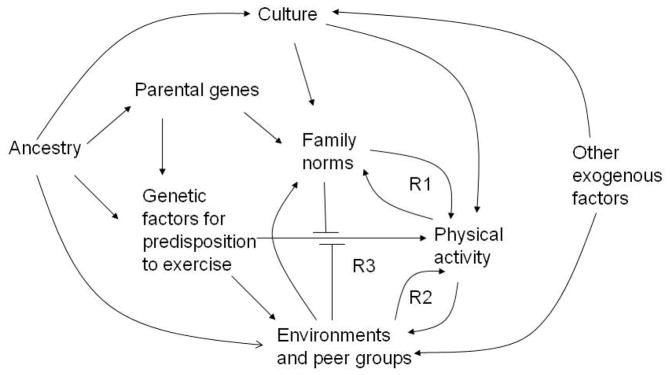

Another example of gene-environment dynamics is provided in figure 2. Recent work has suggested that genetic variants may be related to a greater predisposition to exercise.(46) A simplistic interpretation is that exercise levels are genetically determined and the standard statistical approach would be to estimate the impact of genes on physical activity by isolating the genetic effect after adjusting for other factors. But the system in which these genes operate may be much more complex (figure 2). If genetic factors truly influence the predisposition to exercise, parental genes (which are linked to the genes of their offspring) may partly shape the exercise norms at home. In addition, the offspring’s genes could be related to the selection into peer-groups and environments conducive to exercise. Family norms, peer behaviors, and environments may affect physical activity through mechanisms that have nothing to do with genes. They may also modify the relation between genes and physical activity, enhancing their effects. Physical activity behavior may also have reinforcing effects on environments and norms (R1 and R2 in figure 2). Another reinforcing cycle involves effects of environments on family norms, effects of norms on physical activity behaviors, and effects of behaviors on environments (R3, figure 2). Persons with shared ancestry (which may or may not be related to the physical activity genes) may also share norms/cultural values or be more likely to live in certain types of environments (influenced by other exogenous factors), which may have a much stronger causal effect on physical activity than genes. Failure to account for these relations would result in simplistic misrepresentations of the “causes” of health disparities.

Figure 2.

The interplay of genes and environment: the role of gene-environment interaction and correlation

The figures utilize a simple notation in which a single headed arrow for X to Y indicates that X is a cause of Y (e.g. family norms are causally related to physical activity) or that X causes increased exposure to Y (e.g. genetic factors related to exercise predisposition affect selection into exercise promoting environments). A line intersecting a one headed arrow (in the form of a T) indicates that the factor modifies or modulates the relation between X and Y (effect modification in epidemiologic terms). For example in Figure 1 the T-shaped line from structural/physiologic changes that intersects the arrow from environment to gene expression indicates that the structural and physiologic changes modify or modulate the effect of environments on gene expression. Analogously, in figure 5 discrimination modifies the relation between personal resources/preferences and residential location; and stress modifies the relation between location of services and behaviors. Classic positive or negative feedback loops are indicated with an R (reinforcing) or a B (balancing). Reinforcing loops promote or reinforce change in one direction. Balancing loops tend to close the gap between the current state and the desired state (e.g. increases in stress result in health behaviors which reduce stress levels bringing the body back into its desired state). See text for explanation of specific R and B loops. In order to keep figures simple and because variables are not always quantitative, directionality (plus or minus signs associated with the arrows) is not indicated in the figures but the types of relations can be inferred from the description in the text.

How important are early life factors?

Despite the recognition that factors over the lifecourse are likely to play a role in many diseases (47, 48), questions remain regarding the relative importance of early life and the contributions of early life factors to health disparities. Part of the uncertainty results from the analytical methods used, which attempt to isolate the effects or early life from later life factors or examine the association of trajectories over time with later health but are limited in their ability to capture the dynamic processes that shape these effects over time.(49)

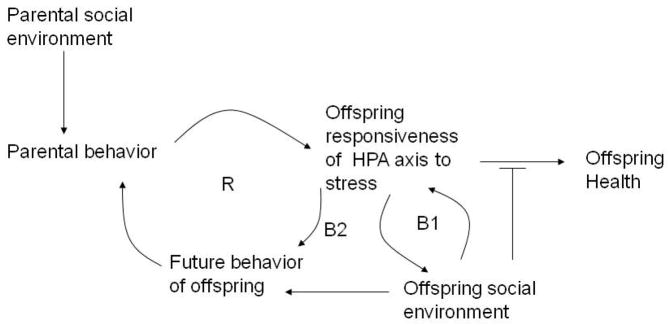

One often noted example involves the impact of early life exposure on stress responsivity later in life. Animal experiments have shown how parental behavior can modify the long term stress responsivity of the offspring through mechanisms involving epigenetic modifications of the glucocorticoid receptor gene.(50, 51) These differences in stress responsivity may interact with stress-generating social exposures over the lifecourse to affect many health outcomes (such as metabolic or hypertension related outcomes). Greater stress responsivity could also promote the selection into social environments that tend to reduce stress responsivity creating a balancing feedback loop B1). In addition, stress responsivity affects the behavior of the offspring towards its own offspring setting the stage for a reinforcing loop (R, Figure 3) that perpetuates and magnifies stress responsivity differentials and their health consequences across generations. A larger balancing feedback (B2) may also operate through which parental behavior (such as less bonding with the offspring) results in greater stress responsivity of the offspring, this greater stress responsivity leads to selection into less stressful environments, and these less stressful environments result in better parental bonding behavior towards future generations (B2). The net intergenerational effect will thus be result of the countervailing influences of R and B2.

Figure 3.

Long term effects and transgenerational transmission of early life experiences (based on Diorio and Meaney, 2007; Weaver et al., 2004) (50, 51)

The figures utilize a simple notation in which a single headed arrow for X to Y indicates that X is a cause of Y (e.g. family norms are causally related to physical activity) or that X causes increased exposure to Y (e.g. genetic factors related to exercise predisposition affect selection into exercise promoting environments). A line intersecting a one headed arrow (in the form of a T) indicates that the factor modifies or modulates the relation between X and Y (effect modification in epidemiologic terms). For example in Figure 1 the T-shaped line from structural/physiologic changes that intersects the arrow from environment to gene expression indicates that the structural and physiologic changes modify or modulate the effect of environments on gene expression. Analogously, in figure 5 discrimination modifies the relation between personal resources/preferences and residential location; and stress modifies the relation between location of services and behaviors. Classic positive or negative feedback loops are indicated with an R (reinforcing) or a B (balancing). Reinforcing loops promote or reinforce change in one direction. Balancing loops tend to close the gap between the current state and the desired state (e.g. increases in stress result in health behaviors which reduce stress levels bringing the body back into its desired state). See text for explanation of specific R and B loops. In order to keep figures simple and because variables are not always quantitative, directionality (plus or minus signs associated with the arrows) is not indicated in the figures but the types of relations can be inferred from the description in the text.

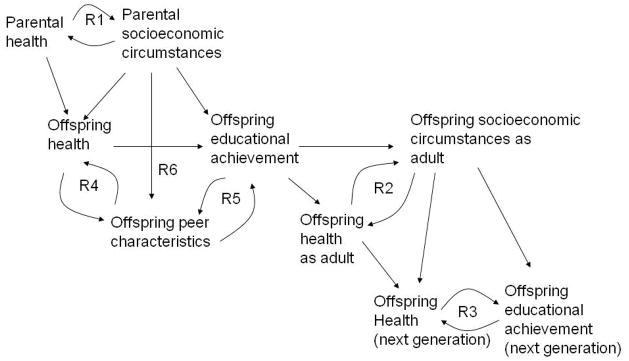

A second example involves the dynamic relations between health and socioeconomic circumstances over the lifecourse (Figure 4). Parental socioeconomic circumstances may affect both the health and educational achievement of children. (52) Childhood health also has consequence for educational achievement and socioeconomic circumstances later in life,(53) which in turn has consequences for the health and educational achievement of the next generation. Parental socioeconomic circumstances may also shape exposure to peer groups, which could affect offspring educational and health outcomes through social influences. Reinforcing feedback loops between health and socioeconomic factors (R1–R3) and between peer characteristics and offspring characteristics (R4 and R5) further complicate these relations. Larger reinforcing feedback loops may also be present (R6): better offspring health results in better educational achievement, which may in turn have influences on peer achievement, and greater peer educational achievement may reinforce better offspring health. The failure to consider these dynamics may hamper our ability to determine the contributions of early life factors to health disparities.

Figure 4.

Dynamic relations between health and socioeconomic circumstances over the lifecourse and across generations

The figures utilize a simple notation in which a single headed arrow for X to Y indicates that X is a cause of Y (e.g. family norms are causally related to physical activity) or that X causes increased exposure to Y (e.g. genetic factors related to exercise predisposition affect selection into exercise promoting environments). A line intersecting a one headed arrow (in the form of a T) indicates that the factor modifies or modulates the relation between X and Y (effect modification in epidemiologic terms). For example in Figure 1 the T-shaped line from structural/physiologic changes that intersects the arrow from environment to gene expression indicates that the structural and physiologic changes modify or modulate the effect of environments on gene expression. Analogously, in figure 5 discrimination modifies the relation between personal resources/preferences and residential location; and stress modifies the relation between location of services and behaviors. Classic positive or negative feedback loops are indicated with an R (reinforcing) or a B (balancing). Reinforcing loops promote or reinforce change in one direction. Balancing loops tend to close the gap between the current state and the desired state (e.g. increases in stress result in health behaviors which reduce stress levels bringing the body back into its desired state). See text for explanation of specific R and B loops. In order to keep figures simple and because variables are not always quantitative, directionality (plus or minus signs associated with the arrows) is not indicated in the figures but the types of relations can be inferred from the description in the text.

What are the relative roles of people and places in disparities?

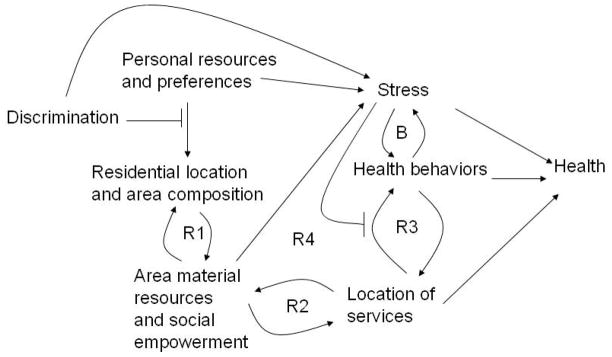

Although many studies have documented important differences in neighborhood physical and social environments by race/ethnicity or socioeconomic position the extent to which these neighborhood differences contribute to disparities in health has remained elusive. This may be due in part to the virtually exclusive analytical focus on isolating the effects of context and composition. A crucial need is a more nuanced understanding of how the linked processes of residential segregation, differential location of health related resources, and the behaviors of residents dynamically affect health differentials.(15) For example, persons are sorted into neighborhoods based on preferences and resources modified (or modulated) by discrimination (figure 5). Area composition affects the material and advocacy power of residents which in turn reinforces area composition (R1). Area resources affects the location of services (e.g. stores offering cheaper unhealthy food tend to locate in poorer neighborhoods) and the presence of services affects area resources (R2). The location of services shapes and is in turn reinforced by the behaviors of residents (proximity of healthy foods affects food purchasing patterns and the purchasing behaviors of residents affect what is sold) (R3). (54) Stress related to disadvantage, discrimination or neighborhood factors can lead to coping behaviors such as increasing fat intake,(55) which help reduce levels of stress (creating a negative or balancing feedback loop, B). Although they may help reduce stress, these behaviors may also have adverse physical health effects through other mechanisms. The extent to which residents adopt certain coping behaviors in response to stress may also be modified by the environmental context. For example, residents may cope with stressors by increasing their fat intake, especially if high fat foods (such as fast foods) are easily available in the neighborhood. Other larger reinforcing loops are also possible. For example, area deprivation may result in greater stress, greater stress may lead to greater fat intake, greater fat intake may promote availability of fast food stores, which in turn may drive down property prices, further increasing area deprivation (R4). Spatial and non spatial social networks (not shown in figure) may also create dependencies in behaviors that reinforce or buffer the impact of environmental factors.

Figure 5.

Dynamic relations between area factors, individual-level factors, and health outcomes

The figures utilize a simple notation in which a single headed arrow for X to Y indicates that X is a cause of Y (e.g. family norms are causally related to physical activity) or that X causes increased exposure to Y (e.g. genetic factors related to exercise predisposition affect selection into exercise promoting environments). A line intersecting a one headed arrow (in the form of a T) indicates that the factor modifies or modulates the relation between X and Y (effect modification in epidemiologic terms). For example in Figure 1 the T-shaped line from structural/physiologic changes that intersects the arrow from environment to gene expression indicates that the structural and physiologic changes modify or modulate the effect of environments on gene expression. Analogously, in figure 5 discrimination modifies the relation between personal resources/preferences and residential location; and stress modifies the relation between location of services and behaviors. Classic positive or negative feedback loops are indicated with an R (reinforcing) or a B (balancing). Reinforcing loops promote or reinforce change in one direction. Balancing loops tend to close the gap between the current state and the desired state (e.g. increases in stress result in health behaviors which reduce stress levels bringing the body back into its desired state). See text for explanation of specific R and B loops. In order to keep figures simple and because variables are not always quantitative, directionality (plus or minus signs associated with the arrows) is not indicated in the figures but the types of relations can be inferred from the description in the text.

Environmental features may also interact dynamically with each other. For example, poor minority areas may have less accessible destinations and may also be less safe, factors that detract from walking and also reinforce each other. These features may magnify residential segregation as persons with more resources and power are able lo locate in and advocate for areas with better environmental attributes. In addition, greater walking may also have consequences for changes in land use mix and safety over time. The dynamic ways in which these factors contribute to health disparities or the consequences we may expect to see as a result of intervening on these factors cannot be fully captured using statistical models.

The three examples (role of genes, lifecourse processes, and neighborhood factors) show how aggregate-level differences in health across social or race/ethnic group may result from processes involving factors at different levels of organization, reinforcing and balancing mechanisms, and dependencies between individuals. They also illustrate, how in the context of systems, there may be multiple different causal pathways to the same outcome, as well as how a single factor can lead to different outcomes depending on other conditions of the system. The schematic examples are rendered even more complex if one considers that many of the relations depicted very simply as arrows between constructs may themselves be non-linear and involve variable time lags, often including long time delays. In all three examples, the dynamics of the system are such that intervening at one point may produce effects that are distant in space and time and unanticipated. As described in more detail in subsequent sections systems approaches allow researchers to explicitly conceptualize dynamic hypotheses or theories such as those encoded in Figures 1–5 and use simulation to explore the implications of alternative dynamic theories.

What kinds of interventions would really help eliminate disparities?

Despite abundant work describing health disparities, little progress has been made in identifying or implementing policies or interventions to eliminate disparities. One possibility is that the underlying and structural causes of disparities have not been addressed. Systems approaches can help create compelling evidence for the need to address these causes, which may be quite distant in space and time from health. The consequences of intervening on these distal and structural causes can be very difficult to convincingly identify in observational or experimental studies. It is under these circumstances, i.e. the desire to evaluate upstream interventions with distal and perhaps unexpected effects in the context of a multiplicity of other factors that may modify their consequences, that systems approaches can be most useful.(10) For example, it would be of great policy interest to assess the long-term health and health disparity consequences (including intergenerational effects) of improving educational quality and educational opportunities for children in poor neighborhoods. Yet this kind of long term data are difficult to obtain and the extent to which results from a given observation can be generalizable to slightly different circumstances is questionable. Systems approaches that capture the types of dynamic relations shown in figure 4 could help identify plausible effects of such interventions. Other examples include evaluating the impact of transportation policy on physical activity disparities, of taxation policies on dietary disparities, or a recently published analysis on the impact on national health reform on health status, cost and equity.(56)

Systems approaches can also help identify previously unidentified leverage points or yield clues as to why certain interventions or policies may not have yielded the expected results, a problem referred to as “policy resistance”.(10) Link and Phelan’s notion of fundamental social causes,(57) an important theoretical framework in health disparities research according to which health inequalities can persist through new mechanisms even when selected intervening factors are blocked, can be thought of as a manifestation of a system that exhibits policy resistance. More generally, the persistence and robustness of health disparities across time, place, and health conditions suggests that important reinforcing and balancing mechanisms are likely to be involved. Understanding the systems that give rise to these inequalities may be necessary to identifying high leverage points and understanding the causes of policy resistance.

How can systems approaches help?

Systems approaches can help move the field of health disparities forward in three ways: (1) systems thinking can promote the development of more sophisticated dynamic conceptual models of the causes of health disparities; (2) systems tools (formal models and simulation) can help explore and refine these models, and explore the effects of different interventions in the context of dynamic relations; and (3) the use of systems approaches can enhance the use of existing data and promote the collection of new types of needed data.

Systems thinking: developing dynamic conceptual models of the causes of health disparities

Any systems approach must begin with the development of what has been referred to as a “mental model”. (25) A mental model encodes “our beliefs about the networks of causes and effects that describe how a system operates, along with the boundary of the model (which variables are included and which are excluded) and the time horizon we consider relevant”. (25)pg 16 Mental models are thus analogous to what health disparitities researchers refer to as conceptual models. The systems approach forces us to be very explicit about these models and incorporate feedbacks and dependencies (ie dynamic relations and hypotheses) into their formulation. A major challenge is setting the boundaries of the system including the relevant time horizon and deciding which variables will be considered exogenous and endogenous, and what things will be excluded. Defining the level of detail necessary in the model is key, and it may be necessary to consider submodels or subsystems linked to each other. The specific examples shown in figures 1–5 are not intended to represent the full set of dynamic relations that might be relevant to the question at hand. A true application of systems to these questions would begin with the development of a much more comprehensive conceptual model and careful definition of the boundaries of the system. The establishment of these boundaries will be based on the overall purpose or goal of the modeling effort as well as on existing knowledge, interdisciplinary exchange, and intuition. The model itself represents a complex hypothesis about the fundamental processes that are involved. Making this model explicit and refining it through scientific exchange, contrast with the real world, and experimentation in a virtual world, is one of the important products of the systems approach. The development of novel and dynamic models of the sources of health disparities may help researchers break away from stalemates and see persistent problems in a new light that could provide the basis for new breakthroughs in understanding.

Systems tools: using “virtual worlds” to refine the dynamic conceptual model, explore fundamental processes, and evaluate interventions or policies

A key methodology in systems approaches is the use of “virtual worlds” i.e. formal models and simulations. In the presence of dynamic complexity, computer simulations based on formal models are necessary to understand the functioning of the system and the implications of the conceptual model proposed.(25) Agent-based models and system dynamics models are two types of systems tools that can be used for this purpose. (58) (59) (25) Through the use of formal models and computer simulations investigators can better understand the implications of their conceptual model and refine it as necessary. They can also gain a richer understanding of the fundamental dynamic relations involved and identify unanticipated leverage points. Even if they do not provide definitive answers, modeling approaches also allow thoughtful initial exploration of the plausible impacts of policies and interventions.

By definition no model can be a complete representation of reality since simplification is inherent in model building. There is a tension in the model building process between using models to estimate the impact of an intervention on the system in real life settings and using models to obtain basic insights about fundamental processes. Estimating the effects of interventions requires sophisticated modeling efforts supported by abundant data. In addition, building models that can be reliably used for estimating the impact of a specific intervention or policy can be challenging when the basic underlying dynamics are still poorly understood. Large and complicated models also rapidly become difficult to test.

Another use of special utility in the early stages of the applications of these methods is the use of modeling to gain fundamental insights into basic dynamics of the system and identify possible new leverage points. When used for this purpose the model building enterprise begins simple. As the model’s functioning becomes understood, new components are added progressively. If the model is too simple, and fundamental elements of the dynamics are omitted, the insights we obtain may be at best incomplete and at worst incorrect. Nevertheless, especially in situations where dynamics are still very poorly understood (as in the case of health disparities) beginning with very basic models which can then be expanded or linked to other models as their dynamics are better understood may be a useful strategy. Even very simple models are helpful as they can serve for proof-of-principle type exercises, can generate new questions, and may stimulate necessary data collection efforts.

Enhancing the use and collection of relevant data: putting together available data and motivating new data collection efforts

Empirical data are of importance in the formulation and refinement of the dynamic hypotheses reflected in the conceptual model. In addition, data relate to the building of formal models and simulation in two ways. First they provide support for specific parameters of the formal model. Second they provide information on patterns and distributions against which summaries of simulated results can be compared. In the area of health disparities, the process of model building may make it quickly apparent that even for simple models the types of data necessary to support specific parameters is often unavailable. When the purpose of the model is to enhance understanding of fundamental processes, even exercises with limited data can yield useful insights. They can also serve as the motivation for new and different types of data collection in the future. The utility of systems modeling to integrate and make the best use possible of existing data, identify crucial data gaps, and explore processes in the context of limited data are important benefits of these approaches in health disparities research.

It has been noted that strictly speaking model validation is impossible.(25) However, there are a number of things researchers can do to enhance the credibility of their model for a specific purpose. Model building and checking is an iterative process that combines qualitative and quantitative knowledge of modeled processes, comparison of model output to various types of external data, and a number of tests and sensitivity analyses that can be used to identify flaws and improve models (e.g. (25, 60, 61)). Pattern replication is often taken as a sign (although not necessarily proof) that the model captures basic underlying process relevant to the problem being studied. However it is important to note that these models are not intended to be predictive models. The development and assessment of systems models is very different from the development and assessment of models used for prediction and forecasting. Model validation remains an active area of research and discussion within the systems field.

Conclusion

Health disparities research has reached a series of road blocks in explaining the causes of disparities and in identifying the most effective interventions or policies to eliminate disparities. The use of analytical methods which primarily focus on identifying “independent” effects may be hampering progress and constrains even the questions that are asked. Thinking about dynamic processes, making them explicit through the formulation of dynamic conceptual models, and exploring these processes through formal models and computer simulations, may stimulate innovation in the field, and could help identify novel intervention points. Systems thinking and modeling may also generate new questions which can then be investigated using empirical data. Aside from their utility in knowledge generation, systems methods can also provide experiential learning opportunities to diverse actors and stakeholders and allow them to contrast alternative dynamic hypotheses of the causes of health disparities. (10) For these reasons systems thinking and systems methods are a welcome addition to our toolkit.

More generally, systems thinking can provide an organizing conceptual framework though which factors at different levels and of different domains can be explicitly integrated dynamically in understanding health disparities. Systems tools allow explicit exploration of these relations. The philosophy behind the systems approach will resonate with many health disparities researchers since as noted by Forrester “In the complex system… causes are usually found, not in prior events, but in the structure and policies of the system…”(62)pp 9–10 Systems approaches allow us to make this structural causation explicit and concrete so that it can be clearly communicated and so that the impact of different interventions can be evaluated. However, the use of systems approaches also raises numerous challenges. It would be a mistake to expect these approaches to solve all problems. Most likely they will serve to complement rather than replace other approaches. The onus is on the scientific community to use these models to answer meaningful scientific questions so that they are more than clever computer games. In an ideal world, there would be an iterative relationship between systems approaches and traditional data collection and analysis efforts, by which dynamic modeling both stimulates new data collection and analyses of empirical data, and serves as an organizing principle though which multiple types of data can be put back together to better represent the underlying processes that are driving the patterns we see.

Understanding the causes of health disparities requires understanding how the dynamic relationships between factors at different levels of organizations result in the “emergence” of health differences across groups. The key question is no longer about partitioning group and individual effects or social and biological effects but rather about understanding how these dynamically relate to generate the macro patterns that we see. By allowing us to hypothesize these processes in detail, and explore and test them through formal models and simulation, systems approaches give us the opportunity to move beyond the metaphors to make the connections and relations explicit, so that they are real and tangible (rather than abstract and metaphorical) and so that we can not only identify useful interventions and policies, but also, and most importantly, motivate them in a compelling way.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Center for Integrative Approaches to Health Disparities (P60MD002249 from the National Institute for Minority Health and Health Disparities), from the Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences at the NIH (contract #HHSN276200800013C) and by the Robert Wood Johnson Health and Society Scholars program.

References

- 1.Stallones R. The epidemiologist as environmentalist. Int J Health Serv. 1973;3:29–33. doi: 10.2190/AM3A-AW5N-5W12-BCUH. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loomis D, Wing S. Is molecular epidemiology a germ theory for the end of the twentieth century? Int J Epidemiol. 1990;19(1):1–3. doi: 10.1093/ije/19.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diez-Roux AV. On genes, individuals, society, and epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;148(11):1027–32. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Philippe P, Mansi O. Nonlinearity in the epidemiology of complex health and disease processes. Theor Med Bioeth. 1998;19(6):591–607. doi: 10.1023/a:1009979306346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McMichael AJ. Prisoners of the proximate: loosening the constraints on epidemiology in an age of change. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;149(10):887–97. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koopman JS, Lynch JW. Individual causal models and population system models in epidemiology. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(8):1170–1174. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.8.1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Homer JB, Milstein B. Communities with Multiple Afflictions: A System Dynamics Approach to the Study and Prevention of Syndemics. 20th International Conference of the System Dynamics Society; 2002; Palermo, Italy: System Dynamics Society; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Materia E, Baglio G. Health, science, and complexity (Editorial) J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59(7):534–5. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.030619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pearce N, Merletti F. Complexity, simplicity, and epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35(3):515–519. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sterman JD. Learning from evidence in a complex world. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(3):505–14. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.066043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glass TA, McAtee MJ. Behavioral science at the crossroads in public health: extending horizons, envisioning the future. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(7):1650–71. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ness RB, Koopman JS, Roberts MS. Causal system modeling in chronic disease epidemiology: a proposal. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17(7):564–8. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2006.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diez Roux AV. Integrating social and biologic factors in health research: a systems view. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17(7):569–74. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Resnicow K, Page SE. Embracing chaos and complexity: a quantum change for public health. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(8):1382–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.129460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Auchincloss AH, Diez Roux AV. A new tool for epidemiology: the usefulness of dynamic-agent models in understanding place effects on health. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168(1):1–8. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galea S, Riddle M, Kaplan GA. Causal thinking and complex system approaches in epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol. 39(1):97–106. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loscalzo J, Kohane I, Barabasi A-L. Human disease classification in the postgenomic era: A complex systems approach to human pathobiology. Molecular Systems Biology. 2007;3(124) doi: 10.1038/msb4100163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lynch M, Conery JS. The origins of genome complexity. Science. 2003;302:1401–04. doi: 10.1126/science.1089370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ideker T, Galitski T, Hood L. A new approach to decoding life: systems biology. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2001;2:343–72. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.2.1.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brown DG. Agent-based models. In: Geist H, editor. The Earth’s Changing Land: An Encyclopedia of Land-Use and Land-Cover Change. Westport CT: Greenwood Publishing Group; 2006. pp. 7–13. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Macy MW, Willer R. From factors to actors: Computational sociology and agent-based modeling. Annual Review of Sociology. 2002;28:143–166. [Google Scholar]

- 22.von Bertalanffy L. General System theory: Foundations, Development, Applications. New York: George Braziller; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller JH, Page SE. Complex Adaptive Systems. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Braveman P. Health disparities and health equity: concepts and measurement. Annu Rev Public Health. 2006;27:167–94. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sterman J. Business dynamics: systems thinking and modeling for a complex world. Boston: McGraw Hill; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Richardson G. Feedback thought in social scence and systems theory. Phipadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Page S. Path Dependence. Quarterly Journal of Political Science. 2006;1:87–115. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koopman J. Modeling infection transmission. Annual Review of Public Health. 2004;25:303–326. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.25.102802.124353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Christakis NA, Fowler JH. The spread of obesity in a large social network over 32 years. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(4):370–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa066082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vickers DM, Osgood ND. A unified framework of immunological and epidemiological dynamics for the spread of viral infections in a simple network-based population. Theor Biol Med Model. 2007;4:49. doi: 10.1186/1742-4682-4-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Risch N. Dissecting racial and ethnic differences. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(4):408–11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe058265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang VO, Sue S. In the eye of the storm: race and genomics in research and practice. Am Psychol. 2005;60(1):37–45. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.60.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Braun L. Race, ethnicity, and health: can genetics explain disparities? Perspect Biol Med. 2002;45(2):159–74. doi: 10.1353/pbm.2002.0023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Duster T. Medicine. Race and reification in science. Science. 2005;307(5712):1050–1. doi: 10.1126/science.1110303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shields AE, Fortun M, Hammonds EM, King PA, Lerman C, Rapp R, et al. The use of race variables in genetic studies of complex traits and the goal of reducing health disparities: a transdisciplinary perspective. Am Psychol. 2005;60(1):77–103. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.60.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sankar P, Cho MK, Condit CM, Hunt LM, Koenig B, Marshall P, et al. Genetic research and health disparities. JAMA. 2004;291(24):2985–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.24.2985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lewontin R. The apportionment of human diversity. In: Hecht MK, Steere WS, editors. Evolutionary Biology. New York: Plenum; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rosenberg NA, Pritchard JK, Weber JL, Cann HM, Kidd KK, Zhivotovsky LA, et al. Genetic structure of human populations. Science. 2002;298(5602):2381–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1078311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tang H, Quertermous T, Rodriguez B, Kardia SL, Zhu X, Brown A, et al. Genetic structure, self-identified race/ethnicity, and confounding in case-control association studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;76(2):268–75. doi: 10.1086/427888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Altshuler D, Daly MJ, Lander ES. Genetic mapping in human disease. Science. 2008;322(5903):881–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1156409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mountain JL, Risch N. Assessing genetic contributions to phenotypic differences among ‘racial’ and ‘ethnic’ groups. Nat Genet. 2004;36(11 Suppl):S48–53. doi: 10.1038/ng1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Olden K, White SL. Health-related disparities: influence of environmental factors. Med Clin North Am. 2005;89(4):721–38. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cole S. Social regulation of human gene expression. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2009;18:132–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01623.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Freese J. Genetics and the social science explanation of individual outcomes. AJS. 2008;114 (Suppl):S1–35. doi: 10.1086/592208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Klonoff EA, Landrine H. Is skin color a marker for racial discrimination? Explaining the skin color-hypertension relationship. J Behav Med. 2000;23(4):329–38. doi: 10.1023/a:1005580300128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.DEM MH, Liu YJ, Boomsma DI, Li J, Hamilton JJ, Hottenga JJ, et al. Genome-Wide Association Study of Exercise Behavior in Dutch and American Adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009 doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181a2f646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lynch J, Smith GD. A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology. Annu Rev Public Health. 2005;26:1–35. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Galobardes B, Lynch JW, Smith GD. Is the association between childhood socioeconomic circumstances and cause-specific mortality established? Update of a systematic review. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62(5):387–90. doi: 10.1136/jech.2007.065508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ben-Shlomo Y, Kuh D. A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology: conceptual models, empirical challenges and interdisciplinary perspectives. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31(2):285–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Diorio J, Meaney MJ. Maternal programming of defensive responses through sustained effects on gene expression. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2007;32(4):275–84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weaver IC, Cervoni N, Champagne FA, D’Alessio AC, Sharma S, Seckl JR, et al. Epigenetic programming by maternal behavior. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7(8):847–54. doi: 10.1038/nn1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Case A, Lubotsky D, Paxson C. Economic status and health in childhood: the origins of the gradient. American Economic Review. 2002;92:1308–1334. doi: 10.1257/000282802762024520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Case A, Paxson C. Children’s health and social mobility. Future Child. 2006;16(2):151–73. doi: 10.1353/foc.2006.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Auchincloss AH, Diez Roux AV, Riolo R, Brown D. An agent-based model of income inequalities in diet in the context of residential segregation. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.10.033. under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dallman MF, Pecorary N, Akana SF, la Fleur SE, Gomez F, Houshyar H, Bell ME, Bhatnagar S, Laugero KD, Manalo S. Chronic stress and obesity: a new view of “comfort food”. PNAS. 2003;100(20):11696–11701. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1934666100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Milstein B, Homer J, Hirsch G. Analyzing national health reform strategies with a dynamic simulation model. Am J Public Health. 100(5):811–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.174490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Link BG, Phelan J. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. J Health Soc Behav. 1995;(Spec No):80–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Epstein JM. Generative Social Science: Studies in Agent-Based Computational Modeling. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Homer JB, Hirsch GB. System dynamics modeling for public health: background and opportunities. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(3):452–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.062059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Forrester S, Senge P. Tests for building confidence in system dynamics models. In: Legasto AFJ, editor. System Dynamics. New York, NY: North-Holland; 1980. pp. 209–228. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Windrum P, Fagiolo G, Moneta A. Empirical Validation of Agent-Based Models: Alternatives and Prospects. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation. 2007;10(2):8. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Forrester J. Urban dynamics. Waltham, MA: Pegasus Communications; 1969. [Google Scholar]