Abstract

Angiosarcomas (AS) represent a heterogeneous group of malignant vascular tumors that may occur spontaneously as primary tumors or secondarily after radiation therapy or in the context of chronic lymphedema. Most secondary AS have been associated with MYC oncogene amplification, while the role of MYC abnormalities in primary AS is not well defined. Twenty-two primary and secondary AS were analyzed by array-comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH) and by deep sequencing of small RNA libraries. By aCGH and subsequently confirmed by FISH, MYC amplification was identified in three of six primary tumors and in eight of 12 secondary AS. We have also found MAML1 as a new potential oncogene in MYC-amplified AS. Significant up-regulation of the miR17-92 cluster was observed in MYC-amplified AS compared to AS lacking MYC amplification and the control group (other vascular tumors, non-vascular sarcomas). Moreover, MYC-amplified AS were associated with a significantly lower expression of thrombospondin-1 (THBS1) than AS without MYC amplification or controls. Altogether, our study implicates MYC amplification not only in the pathogenesis of secondary AS but also in a subset of primary AS. Thus, MYC amplification may play a crucial role in the angiogenic phenotype of AS through up-regulation of the miR-17-92 cluster, which subsequently downregulates THBS1, a potent endogenous inhibitor of angiogenesis.

INTRODUCTION

Angiosarcoma (AS) represents a rare (<2%) subgroup of soft tissue sarcomas characterized by an aggressive clinical behavior (Fletcher et al., 2002). Radical surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy when indicated represent the cornerstone of treatment for patients with localized disease. However, despite an adequate locoregional treatment, up to 50% of patients will develop metastatic relapse and will die of disease (Fayette et al., 2007). The genetic and molecular aberrations involved in AS tumorigenesis remain poorly understood. We and others have recently shown that a particular subset of AS, those arising in a previously radiated area, is characterized by a consistent amplification of the MYC oncogene in chromosome band 8q24.21 (Manner et al., 2010; Guo et al., 2011). So far, such amplifications of MYC have not been reported in primary AS. MYC plays a crucial role in growth control, differentiation and apoptosis, and its aberrant expression is associated with several cancers (Adhikary and Eilers, 2005; Albihn et al., 2010). Interestingly, recent studies have also demonstrated a major contribution of MYC to tumor angiogenesis (Baudino et al., 2002; Dews et al., 2006; Gordan et al., 2007; Dang et al., 2008). One of the major mechanisms involved in MYC-induced angiogenesis is the up-regulation of the miR-17-92 microRNA cluster, the predicted targets of which include thrombospondin-1 (THBS1), encoding a potent endogenous inhibitor of angiogenesis, and connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), encoding an extracellular matrix (ECM)-associated molecule involved in angiogenesis and metastatic progression (Dews et al., 2006). We hypothesize that this molecular process is frequent in AS, at least in those tumors carrying an amplification of MYC, and may play a crucial role in the tumorigenesis of such vascular tumors. Thus, we used genome-wide array comparative genomic hybridization and deep sequencing of small RNA libraries in a group of 22 AS patients in order to investigate this pathogenetic mechanism.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient and Samples

Twenty-two AS and four other vascular tumors (two epithelioid hemangiomas and two epithelioid hemangioendotheliomas) were included in this study on the basis of availability of frozen material for molecular studies. The clinico-pathologic characteristics are listed in Table 1. Diagnoses were established according to the World Health Organization Classification of Tumors (Fletcher et al., 2002). This study was approved by the institutional review board.

Table 1.

Clinicopathologic characteristics of AS and types of platforms investigated

| Case ID | Age | Sex | Previous RT-therapy | Chronic Lymphedema | Primary location | MYC amplified by FISH | MYC amplified by aCGH | Micro-RNA deep sequencing | qRT-PCR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AS3 δ | 58 | M | No | No | Femur | NA | Yes | No | Yes |

| AS4 | 63 | F | Yes | No | Breast | Yes | NA | Yes | No |

| AS9 | 70 | M | No | No | Thigh | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| AS10 | 70 | F | Yes | No | Breast | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| AS11 | 50 | M | No | No | Spleen | NA | No | Yes | No |

| AS15 | 61 | F | Yes | No | Breast | NA | Yes | No | Yes |

| AS20 | 56 | F | Yes | No | Breast | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| AS27 | 37 | F | No | No | Breast | No | NA | Yes | No |

| AS29 | 75 | F | Yes | No | Breast | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| AS30 | 38 | F | Yes | No | Head & Neck | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| AS31 | 79 | M | No | No | Scalp | No | NA | Yes | Yes |

| AS32 | 76 | F | Yes | No | Breast | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| AS38 | 74 | F | Yes | Yes | Forearm | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| AS39 | 84 | M | Yes | Yes | Arm | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| AS68 | 80 | F | Yes | No | Breast | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| AS70 δ | 38 | F | No | No | Breast | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| AS73 | 83 | F | Yes | No | Breast | NA | Yes | Yes | No |

| AS76 | 76 | M | Yes | No | Bladder | NA | No | Yes | No |

| AS85 | 76 | F | Yes | No | Breast | Yes | NA | Yes | No |

| AS123 | 76 | F | Yes | No | Breast | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| AS124 | 57 | M | No | No | Head & Neck | NA | No | Yes | No |

| AS125 δ | 73 | F | No | No | Breast | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Other vascular tumors | |||||||||

| Age | Sex | Histology | Primary location | Micro-RNA deep sequencing | qRT-PCR | ||||

| AS78 | M | 68 | EHE | Arm | No | Yes | |||

| AS80 | M | 41 | Epithelioid hemangioma | Chest wall | Yes | No | |||

| AS84 | M | 31 | Epithelioid hemangioma | Metatarsal bone | Yes | No | |||

| EHE74 | M | 44 | EHE | Liver | No | Yes | |||

RT, radiation therapy; EHE: epithelioid hemangioendothelioma;

primary AS tumors that showed MYC amplification by aCGH

Array-CGH

Genomic DNA was isolated from frozen tumor tissue by phenol/chloroform extraction and quality was confirmed by spectrophotometry and electrophoresis. Array CGH analysis was performed as described previously (Thomas et al., 2011). Briefly, tumor and reference DNA samples were labeled with Cyanine-3-dUTP and Cyanine-5-dUTP, respectively, by random priming (Agilent Enzymatic Labeling Kit, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). The reference sample comprised a pool of DNA from multiple clinically healthy donors (Promega, Madison, WI) of the same gender as the AS patient. The labeled probes were combined and hybridized to a ~180,000-feature, genome-wide oligonucleotide CGH array (design 052252, Agilent Technologies). Arrays were scanned at 5μm resolution using an Agilent G2565CA scanner. Image data were processsed with Feature Extraction version 10.10 and Genomic Workbench version 6.5 (Agilent Technologies). Data were filtered to exclude probes exhibiting non-uniform hybridization or signal saturation and were normalized using the centralization algorithm with a threshold of six. The ADM2 algorithm was used to define CNAs using a ‘three probes minimum’ filter and a threshold of six with a fuzzy zero correction. A genomic copy number amplification was defined as a region within which the log2 ratio of tumor DNA to reference DNA exceeded 2.0. The distribution of aberrations within all tumors of the same subtype (primary or secondary) was evaluated using the ‘common aberration’ function of Genomic Workbench, to identify statistically significant trends. The ‘differential aberration’ function was similarly used to compare the genomic profiles of all primary tumors with all secondary tumors, to identify aberrations whose DNA copy number status was significantly associated with tumor subtype.

Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH)

FISH analysis was performed by hybridization of bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) probes, covering MYC (RP11-440N18; 8q24.21:128,596,756-128,777,986), FLT4 (RP11-586L9; 5q35.3:179,971,355-180,139,031), MAML1 (RP11-828P1; 5q35.3:179,128,722-179,355,313) and two reference probes from the 5q33.3 region (RP11-583A20; chr5:158,433,114–158,602,540 and RP11-117N12; chr5:158,645,646-158,819,496) onto 4μm sections of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue from each tumor. BAC clones were chosen according to their genomic location as defined in the UCSC genome browser (http://genome.ucsc.edu). The BAC clones were obtained from BACPAC sources of Children’s Hospital of Oakland Research Institute (CHORI) (Oakland, CA) (http://bacpac.chori.org). BAC DNA was isolated according to the manufacturer’s instructions, labeled with different fluorochromes in a nick translation reaction, denatured, and hybridized to pretreated slides. Slides were then incubated, washed, and mounted with DAPI in an antifade solution, as previously described (Antonescu et al., 2010). The genomic location of each BAC set was verified by hybridizing them to normal metaphase chromosomes. Two hundred interphase nuclei from each tumor were examined using a Zeiss fluorescence microscope (Zeiss Axioplan, Oberkochen, Germany), controlled by Isis 5 software (Metasystems).

Micro-RNA Sequencing

Total RNA was extracted from frozen tumor tissue using Trizol reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Small RNA cDNA libraries were prepared from 16 AS and two other vascular tumors as previously described (Hafner et al., 2010). In 20 μl reactions, 2 μg total RNA was ligated to 100 pmol adenylated 3′ adapter containing a unique pentamer barcode at the 5′ end using 1 μg Rnl2(1–249)K227Q (purified from E. coli containing pET16b-Rnl2(1–249)K227Q [Addgene, Cambridge, MA]), in 50mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6; 10mM MgCl2; 10mM 2-mercaptoethanol; 0.1 mg/ml acetylated bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and 15% DMSO for 16 hours on ice. After ligation, up to 20 samples bearing unique barcodes were pooled and purified on a 15% denaturing polyacrylamide gel. RNAs of 45 and 50 nucleotides were excised from the gel, eluted, and ligated to 100 pmol 5′ oligoribonucleotide adapter (GUUCAGAGUUCUACAGUCCGACGAUC) as described above for the 3′ adaptors, except that reactions contained 0.2mM ATP and RNL1 instead of RNL2(1–249) K227Q and were incubated for 1 h at 37°C. Ligated small RNAs were purified on a 12% polyacrylamide gel, reverse transcribed using SuperScript III Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and amplified by PCR. The forward primer was AATGATACGGCGACCACCGACAGGTTCAGAGTTCTACAGTCCGA; reverse transcription and reverse primer was CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGA. On average 1,265,133 (range 332,816–2,543,130) sequence reads of miRNAs were obtained per sample.

Real-time RT-PCR

One μg of total RNA was reverse-transcribed using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA) at 25°C for 10 min, 37°C for 120 min, 85°C for five min and hold at 4°C. Twenty ng/μl of resultant cDNA was used in a Q-PCR reaction using an 7500 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA) and pre-designed TaqMan ABI Gene expression Assays (Hs_01070499_m1 for MAML1; HS00905030_m1 for MYC; Hs_00962908_m1 for THBS1; HS_00170014_m1 for CTGF). Amplification was carried at 95°C for 10 min, and 40 cycles (95°C for 15 sec, 60°C for one min). To calculate the efficiency of the PCR reaction, and to assess the sensitivity of each assay, we also performed a 5 point standard curve (80, 26.67, 8.88, 2.96, and 0.98 ng/ul). Triplicates CT values were averaged, amounts of target will be interpolated from the standard curves and normalized to GAPDH (reference gene).

Western Blotting

Western blotting (WB) was performed to assess the expression of MAML1 protein in AS with and without MAML1 gene amplification. Frozen tissue from five AS samples (one with MAML1 amplification and four without MAML1 amplification) and cells from the MYC-amplified breast cancer cell line SKBR3 (Guo et al., 2011) were homogenized in RIPA buffer supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Electrophoresis and immunoblotting were done on the protein extracts using 50 μg of protein per sample and the anti-MAML1 monoclonal antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) diluted according to manufacturers’ recommendations. Following hybridization with the secondary anti-rabbit antibody (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA), the blots were incubated with Immun-Star horseradish peroxidase luminal/enhancer (Bio-Rad) and exposed onto Kodak Biomax MR Film (Eastman Kodak Co., Rochester, NY).

Statistical analysis

The count data were normalized/rescaled using DESeq R package (Anders and Huber, 2010). MicroRNAs with less than 10 counts in both type/condition were not considered for further analysis. To determine differentially expressed microRNAs a Binomial test implemented in DESeq package was used with fold-change 2, and False Discovery Rate=0.1.

RESULTS

MYC is amplified in the majority of secondary AS but also in a subset of primary AS

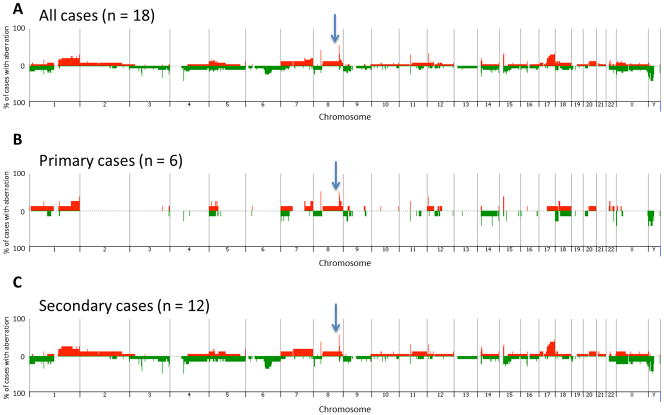

Eighteen cases of AS (6 primary AS and 12 secondary AS) were analyzed by array-CGH, each of which exhibited DNA copy number aberrations. The frequency and distribution of aberrations within the cohort is summarized as a penetrance plot in Fig. 1, which also compares the profiles of genomic gains and losses in primary tumors with those of secondary tumors. A total of 438 aberrations was identified across the cohort of 18 cases, with a mean of 24 aberrations per case (median = 22). The incidence of aberrations within the 12 cases of secondary AS (total = 309 aberrations, range = 12–49, mean per case = 26, median = 23) was highly comparable to that of the six primary AS (total = 129 aberrations, range = 10–35, mean per case = 22, median = 20). No genomic regions showed statistically significant association with tumor subtype when evaluating all tumors within the same subtype, nor when comparing all primary tumors to all secondary tumors. Supplementary Table 1 provides a summary of genomic imbalances within each of the 18 tumors evaluated by aCGH. Strikingly, the MYC locus was found amplified in eight of the 12 secondary AS, but also in three of the six primary AS. The amplification status of MYC was confirmed by FISH in all but two cases, showing consistently > hundreds of copies in the form of hsr or multiple focal amplicons, compared to FLT4 used as control (Fig. 2A). In one case, FISH results were not interpretable despite several attempts (AS3: primary AS arising from bone), while in the other case (AS29: radiation-induced breast AS), there was discordance between FISH showing a MYC amplification and array-CGH showing no imbalance at this locus. Among the four secondary AS lacking MYC amplification, two of them were outside the breast, one in the parotid and the other one in the bladder. In two of these cases the lack of MYC abnormalities was validated by both aCGH and FISH, while in one case no material was available for FISH validation. MYC mRNA expression by Real-Time PCR was assessed in 8 cases of AS [three primary AS with MYC amplification, three secondary AS with MYC amplification and two AS without MYC amplification (used as control group)]. We found an overexpression of the MYC gene in secondary and primary AS with MYC amplification (mean fold change = 2.5 and 2.4, respectively). There were no correlations found with AS histologic subtype (epithelioid, spindle), anaplasia or degree of vascular differentiation and the presence of MYC genomic aberrations.

Figure 1.

Penetrance plots showing the frequency of gain and loss of genomic regions within a) all 18 AS evaluated by aCGH, b) all primary tumors and c) all secondary tumors. Each chromosome is represented on the x-axis, and the y-axis indicates the % gain or loss of the corresponding genomic region within the corresponding population. Gains are shown in red and losses in green. The position of MYC genomic region is indicated by an arrow.

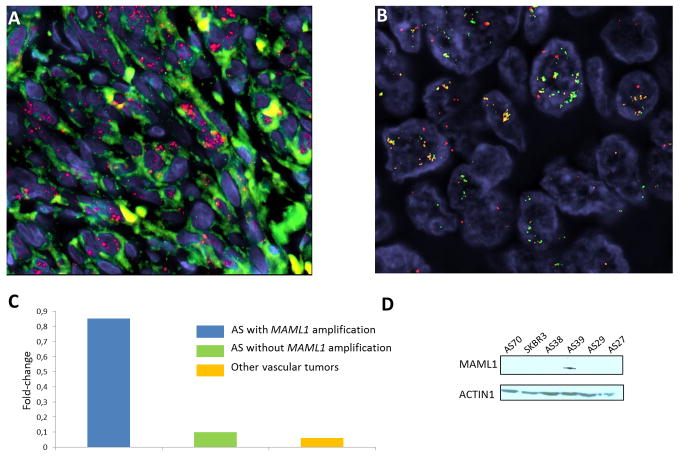

Figure 2.

MYC and MAML1 amplification in AS. (A) FISH analysis with BAC probes RP11-440N18 (MYC) and RP11-586L9 (FLT4) showing high level of MYC amplification (red signal) in a case of primary angiosarcoma (AS125). FLT4 (green signal) is not amplified. (B) FISH analysis with BAC probes RP11-828P1 (MAML1), RP11-586L9 (FLT4) and 5q33.3 region reference probes (RP11-583A20 and RP11-117N12; red) in a chronic lymphedema-associated AS (AS39). MAML1 (orange signal) and FLT4 (green signal) are co-amplified. (C) QRT-PCR analysis measuring MAML1 mRNA expression in AS with MAML1 gene amplification, in AS without MAML1 gene amplification and in other vascular tumors. Gene expression was quantified by QRT-PCR and expressed as mean relative expression (reference gene: GAPDH). (D) Western blotting assessing MAML1 protein expression in AS with MAML1 gene amplification (AS 39), in AS without MAML1 gene amplification (AS27, AS29, AS38, AS70) and in the SKBR3 breast cancer cell line.

The NOTCH pathway effector gene MAML1 (5q35.3) is amplified and overexpressed in a subset of AS

Two cases of MYC-amplified secondary AS displayed co-amplification of the 5q35.3 region, which included FLT4, encoding the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3, as previously reported (Guo et al., 2011), as well as MAML1, which appears relevant for AS genesis since it encodes a crucial effector of the NOTCH pathway. As such, we further analyzed the amplification status of MAML1 in 10 additional cases (two primary AS and eight secondary AS) by FISH. Overall, we have found an amplification of MAML1 in five cases (all secondary AS) out of 28 samples (18%)(Fig. 2B). In all these cases, MAML1 was co-amplified with FLT4. In order to confirm that MAML1 may be a “driver” gene of the 5q35.3 amplicon, we have assessed its mRNA by qRT-PCR (three AS cases with MAML1 amplification, 17 AS cases without MAML1 amplification, and two other vascular tumors) and protein expression by western blotting (one case with MAML1 amplification, four AS cases without MAML1 amplification and the SKBR3 cell line). By qRT-PCR, we have found a significant overexpression of MAML1 in AS with MAML1 amplification in comparison with AS without this aberration (p<0.0001) and other vascular tumors (p<0.0001)(Fig. 2C). By western blotting, we observed that MAML1 protein was expressed in the AS cases with MAML1 amplification, but not in the four AS cases lacking MAML1 amplification nor in the MYC-amplified SKBR3 cell line (Fig. 2D). We did not observe any difference in terms of clinical or pathologic characteristics between AS with and without 5q35 amplification.

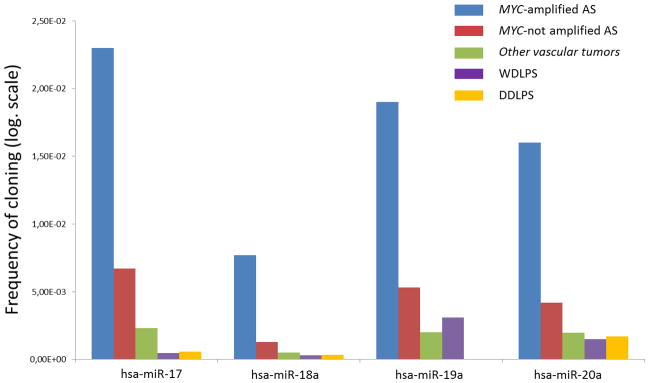

The miR-17-92 cluster is preferentially overexpressed in AS with MYC amplification

We profiled miRNA expression in 16 AS (8 with MYC amplification and 8 without MYC amplification) and two other vascular tumors using deep sequencing of small RNA libraries. By comparing the miRNA expression profile of MYC-amplified AS and MYC unamplified AS, we found forty-three miRNAs that were differentially expressed (Table 2). Among them, miRNAs from the miR17-92 cluster were the most strongly upregulated miRNAs (Fig. 3, Table 2). This overexpression was not the result of genomic amplification, since the 13q31.3 locus encoding the mir-17-92 cluster was balanced in all the 18 cases assessed by array-CGH (data not shown). We also observed this up-regulation in comparison to other vascular tumors and a group of 44 non-vascular sarcomas (well-differentiated/dedifferentiated liposarcomas, WD/DDLPS) without MYC amplification/overexpression and previously analyzed with the same method and in the same laboratory (Ugras et al., 2011) (Fig. 3). Moreover, all the five miRNAs encoded by the 17–92 cluster were overexpressed except miR-19b-1 and miR-92a-1, which were poorly represented in AS (data not shown).

Table 2.

Significant differential expression of the miR 17-92 cluster in MYC amplified AS compared to MYC-unamplified AS, other vascular tumors, well-differentiated liposarcomas (WDLPS) and dedifferentiated liposarcomas (DDLPS)

| Mean clone count | Frequency of cloning (log. scale) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MicroRNA | MYC-amplified AS | MYC unamplified AS | MYC-amplified AS | MYC unamplified AS | FC | FDR |

| hsa-miR-17-92 cluster | 36687 | 15609 | 6.54E-02 | 1.48E-02 | 4.4 | 4E-02 |

| hsa-miR-17 | 12999 | 5137 | 2.3E-02 | 6.7E-03 | 3.4 | 1.8E-02 |

| hsa-miR-18a | 4160 | 1334 | 7.7E-03 | 1.3E-03 | 5.7 | 3.3E-02 |

| hsa-miR-19a | 10107 | 4744 | 1.9E-02 | 5.3E-03 | 3.6 | 1.2E-01 |

| hsa-miR-20a | 9357 | 4344 | 1.6E-02 | 4.2E-03 | 3.8 | 3.5E-02 |

| hsa-miR-92a | 19 | 5 | 3.8E-05 | 1.3E-05 | 2.8 | 4.4E-02 |

| MicroRNA | MYC-amplified AS | Other Vascular Tumors | MYC-amplified AS | Other vascular Tumors | FC | FDR |

| hsa-miR-17-92 cluster | 36687 | 7908 | 6.54E-02 | 6.89E-03 | 9,5 | 4.4E-04 |

| hsa-miR-17 | 12999 | 2606 | 2,29E-02 | 2,32E-03 | 9,8 | 1,1E-03 |

| hsa-miR-18a | 4160 | 609 | 7,68E-03 | 5,24E-04 | 14,6 | 5,8E-04 |

| hsa-miR-19a | 10107 | 2305 | 1,89E-02 | 2,01E-03 | 9,4 | 2,2E-03 |

| hsa-miR-20a | 9357 | 2326 | 1,59E-02 | 1,98E-03 | 8,0 | 5,1E-03 |

| MicroRNA | MYC-amplified AS | WDLPS | MYC-amplified AS | WDLPS | FC | FDR |

| hsa-miR-17-92 cluster | 36687 | 2551 | 6.54E-02 | 5.4E-03 | 12.1 | 2.2E-07 |

| hsa-miR-17 | 12999 | 277 | 2.3E-02 | 4.7E-04 | 48,4 | 2.8E-12 |

| hsa-miR-18a | 4160 | 158 | 7.7E-03 | 2.9E-04 | 26.3 | 1.8E-08 |

| hsa-miR-19a | 10107 | 1374 | 1.9E-02 | 3.1E-03 | 6 | 7.7E-04 |

| hsa-miR-20a | 9357 | 742 | 1.6E-02 | 1.5–03 | 10.8 | 4.8E-06 |

| hsa-miR-92a | 19 | 0 | 3.8E-05 | 0 | NA | 2.9E-10 |

| MicroRNA | MYC-amplified AS | DDLPS | MYC-amplified AS | DDLPS | FC | FDR |

| hsa-miR-17-92 cluster | 36687 | 2551 | 6.54E-02 | 5.4E-03 | 12.1 | 2.2E-07 |

| hsa-miR-17 | 12999 | 549 | 2.3E-02 | 5.9E-04 | 39 | 2.6E-06 |

| hsa-miR-18a | 4160 | 274 | 7.7E-03 | 3.3E-04 | 23.1 | 5.2E-05 |

| hsa-miR-20a | 9357 | 1444 | 1.6E-02 | 1.7E-03 | 9.4 | 1.9E-03 |

FC: fold-change; FDR: false discovery rate

Figure 3.

Differential expression of the miRNA of the miR-17-92 cluster in MYC-amplified AS, in MYC-unamplified AS, in other vascular tumors, in well-differentiated liposarcomas (WDLPS) and in dedifferentiated liposarcomas (DDLPS). (Y axis: frequency of cloning: proportion of miRNA from the total, transformed by the log function).

Overexpression of the miR-17-92 cluster in AS with MYC amplification is associated with down-regulation of thrombospondin-1

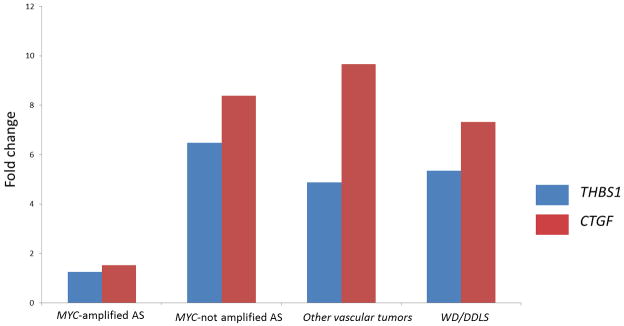

The miR-17-92 cluster contains miR-18a and miR19a that have been shown to affect tumor angiogenesis by down-regulating the mRNA expression of thrombospondin-1 (THBS1) and connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) genes, respectively. Therefore, we compared the expression of these two genes in AS with (n=13) and AS without (n=12) MYC amplification, other vascular tumors (n=2), and WD/DDLPS (n=4) by qRT-PCR. We found a significant down-regulation of THBS1 and CTGF in MYC-amplified AS in comparison with MYC-unamplified AS (THBS1: fold change= 0.15, p=0.02; CTGF: fold change= 0.18; p=0.06), other vascular tumors (THBS1: fold change= 0.20, p=0.004; CTGF: fold change= 0.16; p=0.02) and WD/DDLPS (THBS1: fold change= 0.19, p=0.004; CTGF: fold change= 0.21; p=0.05) (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

QRT-PCR analysis measuring thrombospondin-1 (THBS1) and connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) mRNA expression in MYC-amplified angiosarcomas (AS), in MYC-unamplified AS, in other vascular tumors, in well-differentiated/dedifferentiated liposarcomas (WD/DDLPS). Gene expression was quantified by QRT-PCR, and expressed as mean relative expression (reference gene: GAPDH).

DISCUSSION

We herein report that genomic amplification of MYC is not restricted to radiation-induced AS as previously recognized, but may also occur in a proportion of primary AS. The three cases of primary AS with an amplification of MYC arose in different anatomical sites: breast (n=2) and bone (n=1), suggesting that this genomic event represents a true driver genomic event rather than a site-specific epiphenomenon. A recent study which identified a signature of 135 genes discriminating radiation-induced sarcomas (leiomyosarcomas, osteosarcomas and angiosarcomas) from sporadic sarcomas did not include MYC as part of this signature; the only function found to be significantly deregulated between the two groups being mitochondria (Hadj-Hamou et al., 2011). Moreover, we reported in a previous study the absence of MYC amplification in radiation-induced sarcomas other than angiosarcomas (Guo et al., 2011). Altogether, these data suggest that MYC amplification is not the hallmark of ionizing radiation in the radiation-induced sarcomas, whatever their histology might be.

By extending the number of primary AS cases analyzed by array-CGH and FISH, we report that genomic amplification of MYC is not restricted to radiation-induced AS as previously suggested, but may also occur in a proportion of primary AS. The high incidence of MYC amplification in secondary AS and its occurrence in a subset of primary AS raises the question of its functional role in the tumorigenesis of these highly aggressive vascular tumors. MYC exerts its transcriptional activation function through heterodimerization with MAX (Kretzner et al., 1992). The MYC/MAX heterodimer interacts with specific consensus sequences – the E boxes – in promoters of activated target genes. We previously showed that the MYC/MAX interaction is detected only in AS with MYC amplification (Guo et al., 2011). Moreover, we observed that MAX mRNA expression did not parallel the high levels of MYC in these tumors but showed equally low expression at both mRNA and protein level in AS with and without MYC amplification (Guo et al., 2011). These results suggested that the functional role of MYC in MYC-amplified AS may involve additional or alternative mechanisms outside the MYC/MAX interaction.

Interestingly, recent studies have demonstrated that besides its involvement in the control of cell proliferation, apoptosis and differentiation, MYC contributes also in non-cell-autonomous cancer process such as angiogenesis (Baudino et al., 2002; Dews et al., 2006; Gordan et al., 2007; Dang et al., 2008). The role of MYC in angiogenesis may be of particular importance in vascular tumors, such as AS. Interestingly, one of the major pro-angiogenic events triggered by MYC relies on the activation of the miR-17-92 cluster (Dews et al., 2006). This miRNA cluster, located at 13q31.3, encodes six mature miRNAs: miR-17, miR-18a, miR-19a, miR-19b-1, miR-20a and miR-92a-1 and is a direct transcriptional target of MYC. These miRNAs have been shown to mediate the pro-angiogenic effect of MYC by decreasing the THBS1 (particularly for miR-19a) and CTGF mRNA (particularly for miR-18a) half-life, thereby promoting tumor growth in vivo in a mouse colon carcinoma model (Dews et al., 2006). Thrombospondin-1 (THBS1) is the first endogenous inhibitor of angiogenesis which has been identified. This protein inhibits angiogenesis directly by interacting with specific receptors and stimulating Fas/Fas ligand mediated apoptosis of endothelial cells, but also indirectly by modulating the activity of several angiogenic factors such as FGF-2, VEGF, HGF, or PDGF. There are only very limited data about the status of THBS1 in sarcomas, a decreased expression having been reported in Kaposi sarcoma (Taraboletti et al., 1999) or Ewing sarcoma (Potikyan et al., 2007). Interestingly, the therapeutic efficacy of the thrombospondin-1-mimetic angiogenesis inhibitor ABT-510 has been evaluated in a phase 2 trial including several histological sarcoma subtypes (Baker et al., 2008). Although some patients experienced prolonged disease stabilization, the activity of this agent was considered as modest by the investigators. This conclusion may have been affected by the lack of selection of patients included in the study. Indeed, in regard to AS, our results suggest that only a subset of patients may benefit from such a therapeutic strategy.

CTGF (also known as CCN2) is a member of the so-called CCN family, which includes cysteine-rich 61 [(Cyr61) CCN1], nephroblastoma overexpressed [(Nov) CCN3], Wisp-1/elm1 (CCN4), Wisp-2/rCop1 (CCN5), and Wisp-3 (CCN6) cells (Bradham et al., 1991). Its role in angiogenesis appears ambivalent and depending on the cellular context (Inoki et al., 2002). Our results showing a downregulation of CTGF in MYC-amplified AS favor its involvement in angiogenesis inhibition at least in this specific sarcoma subtype. Besides downregulating THBS1, the mir-17-92 cluster can also promote angiogenesis by attenuating the TGFβ signaling pathway to shut down clusterin expression (Dews et al., 2010).

This cluster can also act as a bona fide oncogene. For instance, miR-17 and miR-20a have been shown to regulate cell cycle progression by targeting E2F1 (O’Donnell et al., 2005; Sylvestre et al., 2007; Woods et al., 2007). However, analysis of our array-expression data did not reveal any significant difference of expression of E2F1 between MYC-amplified and MYC-unamplified AS (data not shown). This result suggests that non-cell-autonomous cancer processes such as angiogenesis represent the main functional consequences of MYC amplification in AS.

Array-CGH data confirmed the presence of genomic imbalances in AS cases without MYC amplification. However, further studies are necessary to identify the oncogenic trigger events of this subset of tumors. Our CGH results showed co-amplification of the 5q35.3 region in two out of 11 cases with MYC amplification. Our previous study suggested FLT4 gene as a potential target gene of this amplicon (Guo et al., 2011). Although, our present results support these findings, they identify MAML1 as a new potential candidate. MAML1 belongs to a family of defined transcriptional co-activators for the Notch pathway (Wu et al., 2000). The Notch pathway plays a crucial role in vascular development and tumor angiogenesis (Ranganathan et al., 2011). There are also several lines of evidence of an aberrant activation of the Notch pathway in benign vascular tumors such as hemangiomas (Calicchio et al., 2009; Wu et al., 2010; Adepoju et al., 2011). Since several inhibitors of the Notch pathway are currently under clinical development, the finding of MAML1 amplification and overexpression in AS deserves further in vitro and in vivo studies to clarify the functional role of the Notch pathway in AS-genesis and as potential therapeutic target.

AS represents a heterogeneous group of malignant vascular tumors, occurring not only in different anatomical locations, but also in distinct clinical settings, such as after radiation therapy or in association with chronic lymphedema. This clinical heterogeneity mirrors the genetic heterogeneity of AS. We have previously shown that despite their consistent morphology, radiation-induced AS are genetically different from the majority of primary AS as a result of MYC amplification. Our present results strongly suggest that this genomic aberration may play a crucial role in the angiogenic phenotype radiation-induced AS and a minority of primary AS through up-regulation of the miR-17-92 cluster. Functional experiments are needed in order to confirm the role of miR-17-92 overexpression and THBS1 downregulation in MYC-amplified AS.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by: PO1 CA047179-15A2 (CRA, SS), P50 CA 140146-01 (CRA, SS), Cycle for survival (CRA, AC), Fondation de France/Fédération Nationale des Centres de Lutte Contre le Cancer.

References

- Adepoju O, Wong A, Kitajewski A, Tong K, Boscolo E, Bischoff J, Kitajewski J, Wu JK. Expression of HES and HEY genes in infantile hemangiomas. Vasc Cell. 2011;3:19. doi: 10.1186/2045-824X-3-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adhikary S, Eilers M. Transcriptional regulation and transformation by Myc proteins. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:635–645. doi: 10.1038/nrm1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albihn A, Johnsen JI, Henriksson MA. MYC in oncogenesis and as a target for cancer therapies. Adv Cancer Res. 2010;107:163–224. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(10)07006-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anders S, Huber W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R106. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-10-r106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonescu CR, Zhang L, Chang NE, Pawel BR, Travis W, Katabi N, Edelman M, Rosenberg AE, Nielsen GP, Dal Cin P, Fletcher CD. EWSR1-POU5F1 fusion in soft tissue myoepithelial tumors. A molecular analysis of sixty-six cases, including soft tissue, bone, and visceral lesions, showing common involvement of the EWSR1 gene. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2010;49:1114–1124. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker LH, Rowinsky EK, Mendelson D, Humerickhouse RA, Knight RA, Qian J, Carr RA, Gordon GB, Demetri GD. Randomized, phase II study of the thrombospondin-1-mimetic angiogenesis inhibitor ABT-510 in patients with advanced soft tissue sarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5583–5588. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.4706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudino TA, McKay C, Pendeville-Samain H, Nilsson JA, Maclean KH, White EL, Davis AC, Ihle JN, Cleveland JL. c-Myc is essential for vasculogenesis and angiogenesis during development and tumor progression. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2530–2543. doi: 10.1101/gad.1024602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradham DM, Igarashi A, Potter RL, Grotendorst GR. Connective tissue growth factor: a cysteine-rich mitogen secreted by human vascular endothelial cells is related to the SRC-induced immediate early gene product CEF-10. J Cell Biol. 1991;114:1285–1294. doi: 10.1083/jcb.114.6.1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calicchio ML, Collins T, Kozakewich HP. Identification of signaling systems in proliferating and involuting phase infantile hemangiomas by genome-wide transcriptional profiling. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:1638–1649. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang CV, Kim JW, Gao P, Yustein J. The interplay between MYC and HIF in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:51–56. doi: 10.1038/nrc2274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dews M, Fox JL, Hultine S, Sundaram P, Wang W, Liu YY, Furth E, Enders GH, El-Deiry W, Schelter JM, Cleary MA, Thomas-Tikhonenko A. The myc-miR-17~92 axis blunts TGF{beta} signaling and production of multiple TGF{beta}-dependent antiangiogenic factors. Cancer Res. 2010;70:8233–8246. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dews M, Homayouni A, Yu D, Murphy D, Sevignani C, Wentzel E, Furth EE, Lee WM, Enders GH, Mendell JT, Thomas-Tikhonenko A. Augmentation of tumor angiogenesis by a Myc-activated microRNA cluster. Nat Genet. 2006;38:1060–1065. doi: 10.1038/ng1855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fayette J, Martin E, Piperno-Neumann S, Le Cesne A, Robert C, Bonvalot S, Ranchere D, Pouillart P, Coindre JM, Blay JY. Angiosarcomas, a heterogeneous group of sarcomas with specific behavior depending on primary site: a retrospective study of 161 cases. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:2030–2036. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher CD, Unni K, Mertens F. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone (2002) Lyon: IARC Press. G; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gordan JD, Thompson CB, Simon MC. HIF and c-Myc: sibling rivals for control of cancer cell metabolism and proliferation. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:108–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo T, Chang NE, Singer S, Maki RG, Antonescu CR. Consistent MYC and FLT4 gene amplification in radiation-induced angiosarcoma but not in other radiation-associated atypical vascular lesions. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2011;50:25–33. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadj-Hamou NS, Ugolin N, Ory C, Britzen-Laurent N, Sastre-Garau X, Chevillard S, Malfoy B. A transcriptome signature distinguished sporadic from postradiotherapy radiation-induced sarcomas. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32:929–934. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafner M, Renwick N, Pena J, Mihailovic A, Tuschl T. Barcoded cDNA libraries for miRNA profiling by next-generation sequencing. In: Hartmann RK, Bindereif A, Schon A, Weshof A, editors. Handbook of RNA Biochemistry. 2. Wennheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH Verlag GmH; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Inoki I, Shiomi T, Hashimoto G, Enomoto H, Nakamura H, Makino K, Ikeda E, Takata S, Kobayashi K, Okada Y. Connective tissue growth factor binds vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and inhibits VEGF-induced angiogenesis. FASEB J. 2002;16:219–221. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0332fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kretzner L, Blackwood EM, Eisenman RN. Myc and Max proteins possess distinct transcriptional activities. Nature. 1992;359:426–429. doi: 10.1038/359426a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manner J, Radlwimmer B, Hohenberger P, Mossinger K, Kuffer S, Sauer C, Belharazem D, Zettl A, Coindre JM, Hallermann C, Hartmann JT, Katenkamp D, Katenkamp K, Schoffski P, Sciot R, Wozniak A, Lichter P, Marx A, Strobel P. MYC high level gene amplification is a distinctive feature of angiosarcomas after irradiation or chronic lymphedema. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:34–39. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell KA, Wentzel EA, Zeller KI, Dang CV, Mendell JT. c-Myc-regulated microRNAs modulate E2F1 expression. Nature. 2005;435:839–843. doi: 10.1038/nature03677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potikyan G, Savene RO, Gaulden JM, France KA, Zhou Z, Kleinerman ES, Lessnick SL, Denny CT. EWS/FLI1 regulates tumor angiogenesis in Ewing’s sarcoma via suppression of thrombospondins. Cancer Res. 2007;67:6675–6684. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranganathan P, Weaver KL, Capobianco AJ. Notch signalling in solid tumours: a little bit of everything but not all the time. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:338–351. doi: 10.1038/nrc3035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sylvestre Y, De Guire V, Querido E, Mukhopadhyay UK, Bourdeau V, Major F, Ferbeyre G, Chartrand P. An E2F/miR-20a autoregulatory feedback loop. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:2135–2143. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608939200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taraboletti G, Benelli R, Borsotti P, Rusnati M, Presta M, Giavazzi R, Ruco L, Albini A. Thrombospondin-1 inhibits Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS) cell and HIV-1 Tat-induced angiogenesis and is poorly expressed in KS lesions. J Pathol. 1999;188:76–81. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199905)188:1<76::AID-PATH312>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas R, Seiser EL, Motsinger-Reif A, Borst L, Valli VE, Kelley K, Suter SE, Argyle D, Burgess K, Bell J, Lindblad-Toh K, Modiano JF, Breen M. Refining tumor-associated aneuploidy through ‘genomic recoding’ of recurrent DNA copy number aberrations in 150 canine non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Leuk Lymphoma. 2011;52:1321–1335. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2011.559802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ugras S, Brill E, Jacobsen A, Hafner M, Socci ND, Decarolis PL, Khanin R, O’Connor R, Mihailovic A, Taylor BS, Sheridan R, Gimble JM, Viale A, Crago A, Antonescu CR, Sander C, Tuschl T, Singer S. Small RNA Sequencing and Functional Characterization Reveals MicroRNA-143 Tumor Suppressor Activity in Liposarcoma. Cancer Res. 2011;71:5659–5669. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods K, Thomson JM, Hammond SM. Direct regulation of an oncogenic micro-RNA cluster by E2F transcription factors. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:2130–2134. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C600252200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu JK, Adepoju O, De Silva D, Baribault K, Boscolo E, Bischoff J, Kitajewski J. A switch in Notch gene expression parallels stem cell to endothelial transition in infantile hemangioma. Angiogenesis. 2010;13:15–23. doi: 10.1007/s10456-009-9161-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L, Aster JC, Blacklow SC, Lake R, Artavanis-Tsakonas S, Griffin JD. MAML1, a human homologue of Drosophila mastermind, is a transcriptional co-activator for NOTCH receptors. Nat Genet. 2000;26:484–489. doi: 10.1038/82644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.