Abstract

The lateral horn (LH) of the insect brain is thought to play several important roles in olfaction including maintaining the sparseness of responses to odors by means of feed-forward inhibition, and encoding preferences for innately meaningful odors. Yet, relatively little is known of the structure and function of LH neurons (LHNs) making it difficult to evaluate these ideas. Here we surveyed more than 250 LHNs in locusts using intracellular recordings to characterize their responses to sensory stimuli, dye-fills to characterize their morphologies, and immunostaining to characterize their neurotransmitters. We found a great diversity of LHNs, suggesting this area may play multiple roles. Yet, surprisingly, we found no evidence to support a role for these neurons in the feed-forward inhibition proposed to mediate olfactory response sparsening; instead, it appears that another mechanism, feed-back inhibition from the giant GABAergic neuron (GGN), serves this function. Further, all LHNs we observed responded to all odors we tested, making it unlikely these LHNs serve as labeled-lines mediating specific behavioral responses to specific odors. Our results rather point to three other possible roles of LHNs: extracting general stimulus features such as odor intensity; mediating bilateral integration of sensory information; and integrating multimodal sensory stimuli.

Introduction

The insect olfactory system has been useful for exploring sensory coding and plasticity (Laurent, 2002; Hansson, 1999; Carey and Carlson, 2011). In the locust, olfactory information is sent from peripheral olfactory organs to the antennal lobe (AL), and is then carried as the oscillatory output of a synchronized population of projection neurons (PNs) (Wehr and Laurent, 1996) to two higher olfactory centers. One center, the mushroom body (MB), has been studied extensively, and is thought to be a site for olfactory learning (Davis, 2011). The other center, the lateral horn (LH), an area defined by the terminal arborizations of PNs in the lateral protocerebrum (Ernst et al., 1977; Homberg et al., 1989), remains poorly understood. What roles might the LH play in olfaction? Two hypotheses are prominent.

Perez-Orive et al. (2002) focused on a population of interneurons in the LH (LHIs, a subtype of LHNs) that extends processes to the MB and appeared to be GABAergic. Kenyon cells (KCs) in the MB receive oscillatory waves of excitatory input directly from PNs; Perez-Orive et al. (2002) proposed the LHIs, which also receive this excitatory input from PNs, then feed it forward, after a brief delay, as inhibition to KCs. KCs would thus receive alternating waves of excitation from PNs and inhibition from LHIs, which together define temporal integration windows that help maintain the minimal and specific odor-elicited spiking observed in KCs.

The LH has also been proposed to encode innate olfactory preferences. Abolishing the MB in Drosophila was linked to deficits in olfactory learning but had little effect on innate olfactory behaviors (de Belle and Heisenberg, 1994; Kido and Ito, 2002). Further, reducing olfactory input to both the MB and the LH caused deficits in innate behaviors, leading Heimbeck et al. (2001) to argue, by exclusion, that the LH could mediate innate, unlearned responses. Consistent with this proposal, anatomical studies in Drosophila showed stereotypical clustering of PN arborizations in the LH (Tanaka et al., 2004; Marin et al., 2002; Wong et al., 2002). Further, the LH appears to provide labeled lines for processing pheromones and mediating sexual behaviors (Jefferis et al., 2007; Ruta et al., 2010). However, whether the LH provides specialized pathways for specific odors processed by the general (non-pheromonal) olfactory system remains unclear, as LHNs could integrate input from diverse PNs (Jefferis et al., 2007), and blocking synaptic transmission in the MB can cause deficits in innate behaviors (Wang et al., 2003; Xia and Tully, 2007).

Information about the morphology and responses of LHNs is needed to test these ideas. Here, we examined the structure and functions of the LH with an anatomical and electrophysiological survey in the locust. Our results are inconsistent with widely accepted views on the composition of the LH, on the mechanisms underlying the sparseness of odor representations and the decoding of the PN input in KCs, and on the role of different LHNs in encoding innate preferences. Our results rather suggest the LH may contribute to concentration coding, bilateral processing, and multimodal integration.

Materials and Methods

Stimulus delivery

Odors were delivered as described previously (Brown et al., 2005). Briefly, 20 ml of odorant solutions were placed in 60 ml glass bottles at dilutions of 10% or 0.1% v/v in mineral oil. Odorants used in our study were: grass volatiles hexanol (hex), octanol (oct), hexanal (hxa) and 1-octen-3-ol (o3l); the synthetic compound cyclohexanone (chx); and non-grass plant volatiles geraniol (ger), citral (cit), and methyl jasmonate (mja), an oviposition deterrent (Daly et al., 2001). Odor pulses were delivered by puffing a measured volume (~0.1 L/min) of the static headspace above the odorants into an activated carbon-filtered air stream (~0.75 L/min) flowing continuously across the antenna. A large (11 cm) vacuum funnel placed behind the antenna quickly removed the odorants. In some experiments a bright white LED (7000 mcd, Radioshack) placed 10 cm from the eyes, and a piezo pulse buzzer (Radioshack) placed 50 cm from the animal, provided visual and auditory stimuli, respectively.

Electrophysiology

Recordings were made from 102 adult locusts (Schistocerca americana) of either sex raised in our crowded colony. Animals were immobilized and the brain was exposed, desheathed, and superfused with locust saline at room temperature as described previously (Stopfer and Laurent, 1999). LFP recordings were made in the MB calyx using blunt glass micropipettes (6-15 MΩ when filled with saline) pulled by a horizontal puller (P87; Sutter Instrument Company). Intracellular recordings were made using sharp glass micropipettes (60–200 MΩ, when filled with 0.5 M potassium acetate or an intracellular dye solution). The signals were amplified in bridge mode (Axoclamp-2B; Molecular Devices), further amplified with a DC amplifier (BrownLee Precision), and sampled at 15 kHz (LabView software; PCI-MIO-16E-4 DAQ cards; National Instruments). After recording, dyes were injected into the neurons iontophoretically using 0.2-2 nA current pulses at 3 Hz for up to 20 minutes.

Histology and Immunostaining

The intracellular dye solution consisted of 1% Neurobiotin (Vector Labs) in 0.2 M LiCl, or 5% Lucifer Yellow, Alexa Fluor 568 or 633 (Invitrogen) filled at the tip with 0.2 M LiCl in the shaft. Histological steps and confocal imaging were performed as described previously (Ito et al., 2008). Anti-GABA immunostaining was performed on whole locust brains containing dye-filled neurons using the procedure of Perez-Orive et al. (2002). Briefly, brains were taken out of the glass slides and gradually hydrated through a series of 100%, 90%, 80%, 70%, 50% and 30% ethanol, and washed with PBS containing 5% Triton X-100 (PBST). Brains were then agitated for 5 h in PBST containing 10% goat serum (PBST-GS), and transferred to fresh PBST-GS containing rabbit anti-GABA (Sigma) at 1:100 dilution. After incubation for 5 days, brains were washed for 4 h in PBST at room temperature and transferred to PBST-GS containing Alexa Fluor 633-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Invitrogen) at 1:100 dilution and incubated for 5 days. They were then washed in PBS, dehydrated through ethanol series, cleared in methyl salicylate and examined by confocal laser scanning microscopy. Confocal stacks were analyzed using public domain software ImageJ (NIH).

Data Analysis

All analyses were performed using custom programs in MATLAB (MathWorks). Peri-stimulus time histograms (PSTHs) of neural activity were estimated by convolving instantaneous firing rate (computed in 20 ms bins, averaged over trials) with a 200 ms Gaussian function. Responsiveness of a neuron was determined by an automated algorithm: a neuron was considered responsive to a stimulus if the PSTH in a 2 s period following stimulus onset changed by more than 3.5 standard deviations from background (Perez-Orive et al., 2002); responsiveness determined by the algorithm was consistent with visual inspection. Sliding-window cross-correlations between the LFP and LHNs were computed using the ‘xcov’ function in MATLAB with the ‘coeff’ normalization option (to minimize the effects of DC shifts and amplitude changes), on 5-40 Hz bandpass filtered LFP and unfiltered LHN recordings, with 150 ms windows and 50 ms shift-interval, and finally averaged over multiple trials for a given cell-odor pair. Cross-correlograms between the LFP and the membrane potentials of LHNs (in Fig. 4) were computed using filtered LHN and LFP recordings; LFP auto-correlograms were computed similarly. The strength of spontaneous cross-correlation was estimated by computing the cross power spectral density between the LFP and the membrane potential of an LHN (both signals centered and scaled with the ‘zscore’ function in MATLAB) in a 2 s period before odor onset, and integrating it over the 15-30 Hz frequency band. Phases of spikes in LHNs with respect to the concurrent cycle of the LFP were estimated by determining their positions relative to the previous (0 radian) and the next (2π radians) peak in the simultaneously recorded LFP, which was band-pass filtered (15-30 Hz). Phases of GGN output (which is non-spiking) with respect to the LFP were estimated by recording GGN membrane potential, and averaging the rows of the GGN-LFP cross-correlograms (i.e. over time) in a 1 s response period, and determining the positions of the peaks immediately before (0 radian) and immediately after (2π radians) the position of zero time lag.

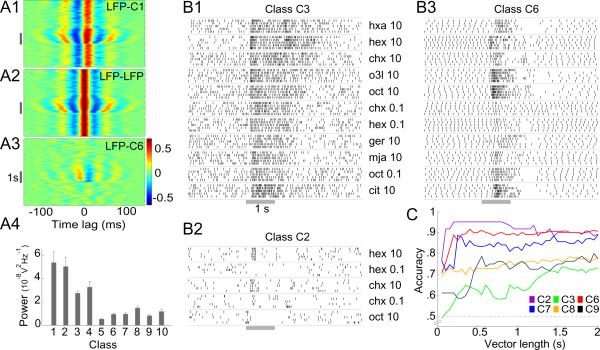

Figure 4.

Response characteristics of LHNs. A: Different types of LHNs vary in the extent to which their activity is correlated with the LFP. A1: Cross-correlogram of subthreshold membrane potential activity in a class C1 LHN with the LFP; A2 shows the LFP auto-correlogram for comparison. A3: Cross-correlation of a β-LN (class C6) and the LFP. Gray bar: odor pulse. Note strong correlations in A1 and A2 even in the absence of odor. A4: Cross power spectra (see Methods; mean±SEM for all recordings in a class), measured over a 2 s period before odor onset, show classes C1-C4 have stronger spontaneous synchrony with the LFP than remaining classes C5-C10 (p < 0.0004; two-tailed two-sample t-test, d.f. = 8). B: Responses of different LHNs contain varying amounts of information about odor identity. Raster plots illustrate the responses of one representative neuron each from classes C2, C3 and C6, to multiple odors (5 trials each, 10 s inter-stimulus interval. Gray bar: odor pulse; for odor list see Materials and Methods). C: Pairwise odor-classification accuracy, as a function of the sample duration (vector length) for different classes of LHNs (chance level, 0.5); n = 3, 6, 10, 6, 13 and 4 odor-pairs for classes C2, C3, C6, C7, C8, C9, respectively. Classes with fewer than 3 odor-pairs or non-spiking responses (C5) were not analyzed.

Classification Task

Because we could not determine with certainty the total number of neurons in each LHN class, we restricted our analysis to the information content of individual LHNs, and report the success rate of an algorithm to classify odors given the responses of each class of LHN. We represented information content of LHNs with vectors of spikes binned in 50 ms windows (selected with reference to the strong synchrony of LHNs with the LFP at ~20 Hz). For all LHNs, we performed pair-wise classification only between an alcohol odor (hex or oct) and a ketone (chx) to ensure accuracy estimates were not biased by the differences in the odors tested for different cells. The classifier first generated a template for each odor by calculating the centroid of the vectors from training trials (50% of all trials), and then classified the remaining (test) trials based on Euclidean distance from the two templates (Stopfer et al, 2003). An accuracy estimate was derived by counting the fraction of correct classifications (expected chance performance is 0.5). Another classifier, based on the k-means algorithm for unsupervised classification, provided similar results (data not shown).

Results

LHNs are diverse

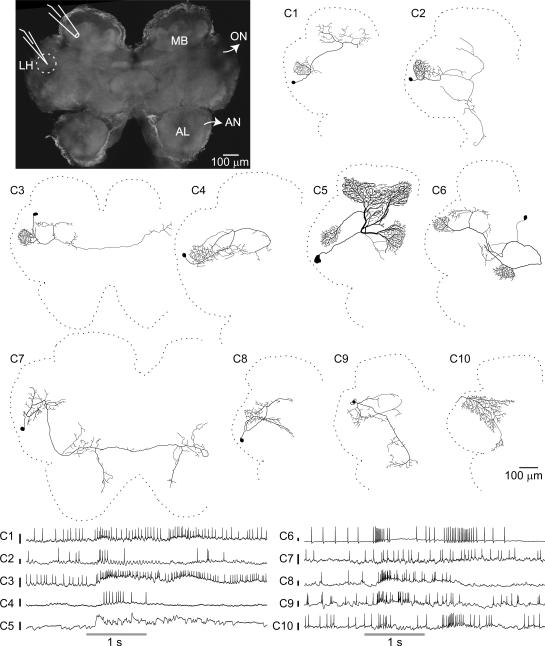

Neurons were impaled, often in a neurite, in the LH region (Fig. 1, top-left) with sharp intracellular electrodes, and their responses to a panel of odorants, and in some cases to a light or a sound stimulus, were tested (see Methods). Recordings were made from a total of 260 cells in 102 animals, providing ~900 cell-stimulus combinations, with up to 10 trials for each (see Table 1 for details). Local field potentials (LFPs) were recorded simultaneously in the MB calyx using an extracellular electrode to measure odor-evoked oscillations. We were able to fully label about a quarter of the recorded neurons with a fluorescent dye, revealing a surprising diversity of neuron morphology. While previous studies in Drosophila based on available lines of genetically-labeled neurons have reported 3 or 4 classes of neurons in the LH (Tanaka et al., 2004; Jefferis et al., 2007; Yu et al., 2010), we found 10 very distinct morphological classes (Fig. 1, Table 1); examples of each class were observed in at least two brains, and each responded to odors. The cell bodies and primary neurites of neurons within a class were found in consistent locations (see examples in Fig. 2A,B). We refer to all neurons (other than PNs) with neurites in the LH as Lateral Horn Neurons, or LHNs, to distinguish them from a subset, the LHIs previously described by Perez-Orive et al. (2002). Although PNs send processes to this region we did not record from them; none of our recordings showed the response characteristics of PNs (phase preference of spiking with respect to the LFP, elaborate and odor-specific spiking patterns), and none of the cells we filled in this region showed the distinctive morphology of a PN. Three of the classes we observed (C1, C5 and C6) have been previously reported in the locust. C1 shows the same morphology defining the LHIs (Perez-Orive et al., 2002). C5 is the giant GABAergic neuron (GGN) that provides feed-back inhibition to the KCs (Papadopoulou et al., 2011). C6 neurons, which also arborize in the β-lobe of the MB, have been previously reported as one of the anatomical subtypes of β-lobe neurons (β-LNs) belonging to the set of MB output cells (Macleod et al., 1998; Cassenaer and Laurent, 2007).

Figure 1.

Anatomical and electrophysiological survey of the lateral horn (LH). Top-left: Flattened confocal stack of an unlabeled locust brain. Dotted circle: the LH; MB: mushroom body calyx; AL: antennal lobe; AN: antennal nerve; ON: optic nerve. Sharp intracellular recordings were made from lateral horn neurons (LHNs) while simultaneous extracellular LFP recordings were made from the ipsilateral MB calyx. Middle: We identified 10 morphologically distinct classes of LHNs, illustrated with hand-traced intracellular dye fills. Somata of C10 neurons were not detected. Bottom: Representative intracellular recordings from the 10 LHN classes, showing their responses to odor presentations (gray bars). Calibration bars next to class labels: 10 mV.

Table 1.

Descriptions of 10 morphological classes of LHNs identified from intracellular fills. Because the boundaries of the LH are not clearly visible in individual fills, we could only determine whether a neuron has dense or sparse projections in the region.

| Class ID (Common Name) | Location of cell body | LH arborization | Other regions of arborization | Times filled | Cell-stimulus pairs recorded for filled neurons | Trials per recording (mean±SD) | GABA-positive neurons / total GABA stains obtained | Comments | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 (LHI) | Middle lateral pr | Dense | MB calyx | 7 | 11 | 9.0±1.6 | 0/2 | Previously proposed to mediate feed-forward inhibition to KCs | Perez-Orive et al., 2002 |

| C2 | Middle lateral pr | Dense | A branch from LH bifurcates: one part goes to posterior pr and another to anterior pr and ventral deutocerebrum | 2 | 7 | 9.3±1.9 | - | ||

| C3 | Posterior lateral pr | Dense | Looping projections in middle/posterior pr; one branch reaches contralateral LH | 6 | 25 | 8.2±2.4 | 0/3 | Projects bilaterally | |

| C4 | Middle lateral pr | Dense | Looping projections in middle/posterior pr | 3 | 10 | 8.7±2.4 | 1/1 | ||

| C5 (GGN) | Middle lateral pr | Dense | MB α-lobe (input); MB calyx (output); MB pedunculus | 15 | 111 | 9.9±0.6 | 3/3 | Non-spiking responses; 9 unfilled neurons could also be identified as GGNs from their characteristic responses. | Papadopoulou et al., 2011; Liu and Davis, 2009 |

| C6 (β-LN) | Posterior medial pr | Dense | MB β-lobe (input); MB pedunculus; looping projections in posterior lateral pr | 9 | 46 | 8.6±3.0 | 0/3 | One of the two types of output neurons reported in MB β-lobe. | Macleod et al., 1998; Cassenaer and Laurent, 2007; Papadopoulou et al., 2011 |

| C7 | Anterior lateral pr | Sparse | Ipsilateral and contralateral anterior medial pr, one branch goes toward ventral deutocerebrum | 4 | 15 | 9.4±1.7 | 0/2 | Projects bilaterally | |

| C8 | Middle lateral pr | Sparse | Posterior lateral pr, anterior medial pr | 12 | 47 | 8.7±2.1 | 2/2 | ||

| C9 | Posterior lateral pr | Sparse | Posterior lateral pr, anterior medial pr, ventral deutocerebrum | 2 | 15 | 7.9±2.5 | - | ||

| C10 | (not identified) | Sparse | Posterior and middle lateral pr, one branch goes toward anterior medial pr | 2 | 13 | 8.1±2.1 | - | Multimodal responses; also shown by 10 unfilled neurons. |

Abbreviations: pr, protocerebrum; MB, mushroom body; LHI, lateral horn interneuron; GGN, Giant GABAergic neuron; β-LN, β-lobe neuron. Classes for which GABA stains were not available are indicated with hyphens.

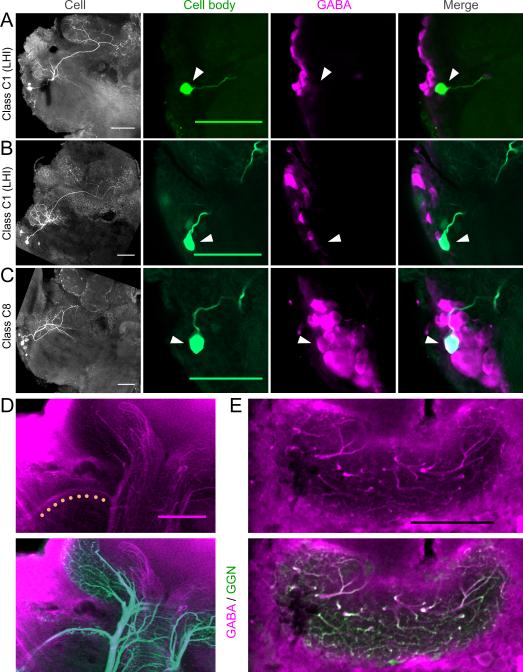

Figure 2.

Source of GABAergic inhibition to the MB calyx. A-C: Dye-filled LHIs projecting to the MB calyx do not label positively for GABA. A-B: LHN class C1 (LHIs). First panel: flattened confocal stack shows neuron's morphology (showing left half of the brain; compare to Fig. 1 for orientation); last three panels show the overlap between the intracellular fill (green) and the GABA immunostain (magenta) in a region near the cell body (marked by arrowheads). The LHIs are GABA-negative but are located near GABA-positive cells. C: LHN class C8. This LHN is GABA-positive but does not project to the MB calyx. D: Top: GABA immunostain shows a GABAergic tract between LH and MB calyx (highlighted with dots). Bottom: intracellular fill of GGN in the same brain shows this tract is a branch of GGN. E: Top: GABA immunostain shows GABAergic fibers in the MB calyx. Bottom: intracellular fill of GGN in the same brain shows most or all of these fibers are branches of GGN. Scale bar in all panels: 100 μm.

In sharp contrast to the sparse spiking observed in KCs, which are targets of the PNs in the MB, (Perez-Orive et al., 2002; Stopfer et al., 2003; Turner et al., 2008; Ito et al. 2008; Honegger et al., 2011), LHNs typically fired spontaneously and showed strong responses to odors (Fig. 1, bottom). These responses varied from simple increases or decreases in firing rate to more complex temporal patterns of spikes. While different classes of LHNs generated somewhat different spiking patterns, responses to different odors within a class were not always more similar to each other than to the responses of other classes. Thus, it was generally not possible, with the sole exception of C5, to use these responses to accurately identify the class of a neuron. We therefore used morphological criteria to classify neurons. C5 neurons (GGN) showed graded odor-responses, did not respond with action potentials to any odor or current stimulus, and could be unambiguously identified by their characteristic sub-threshold activity patterns (Papadopoulou et al., 2011).

LHIs do not provide feed-forward inhibition to the KCs

Perez-Orive et al. (2002) suggested one class of LHN, the LHIs, provides feed-forward inhibition to the KCs in the MB calyx. We recorded from 7 neurons (class C1) that match the key anatomical characteristics of LHIs: they have somata in a cluster near the LH, form dense arborizations in the LH, and project to the calyx of the MB. Consistent with the previous description (Perez-Orive et al., 2002), we found these neurons responded strongly and reliably to all tested odors with spikes and subthreshold membrane potential oscillations (Fig. 1).

We obtained clear immunostaining against gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) in 2 brains containing LHIs with responses characterized by intracellular recordings and morphologies identified by intracellular dye injection. Both revealed the same surprising result: neither LHI labeled positively for GABA. In both brains, other neurons clustered near the LHI were strongly labeled (Fig. 2A,B), indicating our stains were successful and reproducible. These results suggested that, although the LHIs are located near GABAergic cells, the LHIs themselves are not GABAergic. We reexamined the evidence presented by Perez-Orive et al. (2002). These authors did not show immunostaining for individual LHIs, but rather described two types of results from anti-GABA screening of the whole brain. First, they found a cluster of around 60 GABAergic cells near the cell bodies of the LHIs. Second, they identified a GABAergic tract between the LH and the MB calyx, potentially bearing the axons of the LHIs. They also noted that dendrites of KCs intermingle with GABAergic fibers in the calyx region of the MB (Leitch and Laurent, 1996) and that KCs show odor-elicited IPSPs.

Our results suggest other types of neurons underlie all these observations. Class C8 neurons, which have cell bodies near those of the LHIs but do not project to the calyx (Fig. 1), labeled positively for GABA (Fig. 2C). Moreover, C8 cells were identified more frequently (12 times) than the LHIs (7 times), suggesting C8 cells comprise at least a portion of the cluster thought to contain the LHIs. We also identified the GABAergic tract (Fig. 2D) between the LH and the MB calyx described by Perez-Orive et al. (2002). However, our intracellular fill of GGN (class C5, Fig. 1) followed by immunostaining for GABA revealed this tract is actually a branch of GGN (Fig. 2D). Moreover, nearly all the GABAergic fibers we repeatedly observed in the MB calyx overlapped precisely with arbors of GGN, indicating GGN provides by far the greatest source of inhibitory input to the KCs (Fig. 2E). We also identified additional GABAergic fibers of unknown origin running along the pedunculus to the accessory calyx (but not projecting to the LH); because KCs in the olfactory system do not project to the accessory calyx (Laurent and Naraghi, 1994), these fibers are unlikely to inhibit the KCs. Thus, of the two types of neurons (GGN and LHIs) proposed to inhibit KCs, only GGN appears to perform this role.

GGN can account for most roles attributed to LHIs

The LHIs described by Perez-Orive et al. (2002) were suggested to play two important roles in odor coding:

1. Piece-wise decoding of PN input by the KCs

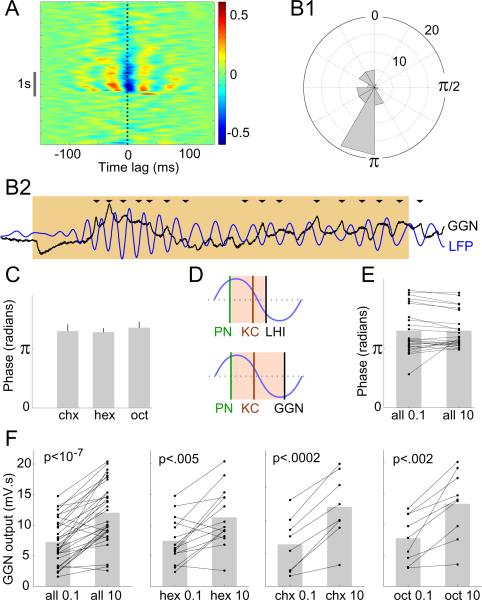

The spikes of the LHIs, biased by their inputs from rhythmically-driven PNs to occur in a specific phase position in every oscillation cycle, have been proposed to provide a mechanism for KCs to decode input from PNs, cycle-by-cycle. This helps KCs to function as coincidence detectors (Perez-Orive et al., 2002; Perez-Orive et al., 2004) responding only to synchronized firing from multiple presynaptic PNs (Jortner et al., 2007). But it is unclear whether the graded output of the non-spiking GGN could perform a similar role. It was shown recently that GGN output intensity correlates with the overall magnitude of the LFP oscillations when viewed across cycles (Papadopoulou et al., 2011). But does this output vary with phase within a cycle? Analyzing the within-cycle phase relationship between GGN and the simultaneously recorded LFP, we made the following observations. First, upon presentation of odors, GGN's membrane potential showed strong oscillatory synchrony with the LFP (Fig. 3A). Second, the phase difference between GGN's membrane potential and the LFP was usually between 180-210 degrees (Fig. 3B1,2), i.e., the peaks of GGN output occurred near the troughs of the LFP. Third, the phase remained unchanged for different odors (Fig. 3C). Together, these observations show the inhibitory drive to the KCs from GGN is strongest at a specific phase of the oscillatory cycle, and this phase remains stable across different odors, potentially enforcing uniformly-sized integration windows within each oscillation cycle over which KCs could integrate the PN input (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3.

GGN-mediated feed-back inhibition is consistent with regulation of temporal integration in KCs. A: Sliding-window cross-correlation diagram (average of 10 trials) shows strong phase-locking between GGN and the LFP; red and blue bands indicate, respectively, peaks and troughs of the cross-correlation. Note the negative correlation at 0 time lag (dotted line) during odor presentation (gray bar). B1: Polar histogram shows precise phase position of GGN output relative to the LFP (n = 48 cell-odor combinations, see Materials and Methods); concentric circles: events per angular bin. B2: Representative simultaneous recording of GGN and the LFP (filtered 15-30 Hz) during an odor presentation (colored background). In most oscillation cycles peak GGN output occurs near the trough of the LFP (highlighted by arrowheads). C: Average GGN phase for three different odors (n = 10, 24 and 14 recordings respectively for cyclohexanone, hexanol, octanol); mean±SEM; one-way ANOVA, F(2,45) = 0.21, p > 0.8, n.s. D: Schematic diagram comparing the integration windows for two models. Upper: Presumed inhibitory spikes in LHIs, occurring after the excitatory spikes in PNs, were proposed to create brief integration windows (colored background) for the KCs within each oscillatory cycle. Lower: GGN output is appropriately timed to form similar integration windows. E: Phase of GGN output does not vary with odor concentration: pairwise comparison of GGN phase evoked by 0.1% and 10% odor-concentrations; n = 24 cell-odor combinations from 12 cells; two-tailed paired t-test; p > 0.9, n.s.; gray bars show the mean. F: Net output of GGN increases with odor concentration: GGN output (membrane potential above the baseline integrated for 2 s following odor-onset) evoked by 0.1% and 10% concentrations of odor (all combined in the first panel); n = 15, 8 and 9 cell-odor pairs respectively for hexanol, cyclohexanone, and octanol; two-tailed paired t-tests.

2. Maintaining sparseness of spiking in KCs across odor concentrations

Increases in odor concentration increase the coincidence of firing among PNs, but, puzzlingly, do not alter the sparseness of firing in the coincidence-detecting KCs (Stopfer et al., 2003). A computational model based on feed-forward inhibition from the LHIs to the KCs suggested that concentration-driven changes in the phase of spiking of LHIs could adjust the integration windows for KCs (Assisi et al., 2007), thus maintaining the sparseness of response in KCs elicited by different concentrations of odors. However, we found the phase of GGN's output did not vary with odor concentration (Fig. 3E). Could GGN maintain the sparseness of firing in KCs by another mechanism? Recently, a computational model (Papadopoulou et al., 2011) suggested that GGN can help maintain the sparseness by increasing its net inhibitory output with the odor concentration, and supported this prediction with tests using one odorant. We confirmed and modestly extended these results by comparing GGN's output elicited by low and high concentrations of three different odorants. We found increasing the concentration of each odor significantly increased the amplitude of GGN's output (Fig. 3F), supporting the role of GGN in maintaining sparse firing of KCs, but by a mechanism different from that proposed for the LHIs.

LHNs and innate odor preferences

Next, we asked whether the connectivity and response properties of different classes of LHNs are consistent with a labeled-line model of encoding innate preferences for odors (Tanaka et al., 2004; Ruta et al., 2010). LHNs are commonly thought to have specific connectivity to PNs and very selective responses to odors (Luo et al., 2010). Our intracellular fills from LHNs showed that classes C1, C2, C3 and C4 form dense, ball-like projections exclusively in the LH (Fig. 1), suggesting these neurons receive densely convergent input from large numbers of PNs. Such input would be expected to generate, even in the absence of odors, membrane-potential fluctuations that closely resemble the LFP, which is established by converging input from many PNs in the calyx (Laurent and Naraghi, 1994). Indeed, we found the membrane potentials of LHN classes C1-C4 were tightly synchronized with the LFP even in the absence of odor (Fig. 4A1); these measures resembled an autocorrelation of the LFP (Fig. 4A2). Classes C1-C4 showed strong spontaneous synchrony with the LFP before odor onset, significantly more than other classes (Fig. 4A4). These anatomical and physiological results both suggest classes C1, C2, C3 and C4 LHNs receive massively convergent input from PNs, consistent with our observation that these cells responded to all the odors we tested.

Although classes C5 (GGN) and C6 (β-LN), too, formed dense projections in the LH, they also arborized heavily in the α- and the β-lobes of the MB, respectively, and are known to receive their primary input from these lobe areas (Cassenaer and Laurent, 2007; Papadopoulou et al., 2011). Further, it was recently shown that silencing KCs by depolarizing GGN also silenced β-LNs (Papadopoulou et al., 2011), indicating β-LNs do not receive direct input from PNs. The responses of GGN and β-LNs were different from those of LHN classes C1-C4, the former synchronizing with the LFP only during odor presentations (Fig. 3A and Fig. 4A3,4). Finally, consistent with results suggesting only classes C1-C4 receive direct and converging input from PNs (see next section), we found concentration-dependent changes in the phases of the spikes of classes C1-C4 but not in those of β-LNs or in the phases of GGN's graded output (Fig. 3E). LHN classes C7, C8, C9 and C10 did not show spontaneous cross-correlations with the LFP (Fig. 4A4), and do not appear to receive massively convergent PN input.

GGN has been shown to respond to all tested odors (Papadopoulou et al., 2011); our recordings confirmed this (data not shown). Here, we report the selectivity of other classes of LHNs. In total, our data set included 171 cell-odor pairs from morphologically identified neurons from classes C1-C10 (excluding GGN). Of these, 170 pairs cleared an automated algorithm's threshold for detecting a significant response to odor presentation (see Methods); visual inspection yielded nearly identical results and showed that the single cell-odor pair whose response did not clear the algorithm's threshold contained a small but reliable inhibitory component.

Thus, all the LHNs we identified (classes C1-C10) responded to all tested odors; notably, in this respect LHNs are less selective than PNs (Wehr and Laurent, 1996). Further, many LHNs showed anatomical and physiological evidence of receiving densely convergent input from PNs, contradicting an earlier proposal (Tanaka et al., 2004). The odorant panel we used in this study, although limited in size, included odors with different types of ecological relevance. Grass volatiles hexanol and hexanal included in the panel are innately attractive to locusts (Sun et al., unpublished observations); yet, responses of LHNs to these odorants were not distinct from responses to other odorants. Because C1-C10 LHNs responded broadly to our panel of odorants we can infer these LHNs are not specialized to respond exclusively to any potentially relevant odors that we did not test. Individual LHNs could show excitatory or inhibitory responses to multiple odors (Fig. 4B1,2), or both excitation and inhibition in sequence in response to a single odor (Fig. 4B3). The odor-evoked firing patterns of some of these broadly-responsive neurons, like those of PNs, contained information that could be used to classify odor identity (Fig. 4B, C; see Methods). After 300-500 ms of odor onset, a time-period found sufficient for making behavioral decisions (Vickers and Baker, 1996), the classification success rate of different classes of LHNs varied widely, from 60% to 95% (Fig. 4C), consistent with the functional diversity of cell-types in the LH. Together, our results lend no support to the idea that LHNs, in general, act as labeled-lines for mediating highly selective behavioral responses to specific, innately meaningful odors.

Simple coding of stimulus intensity

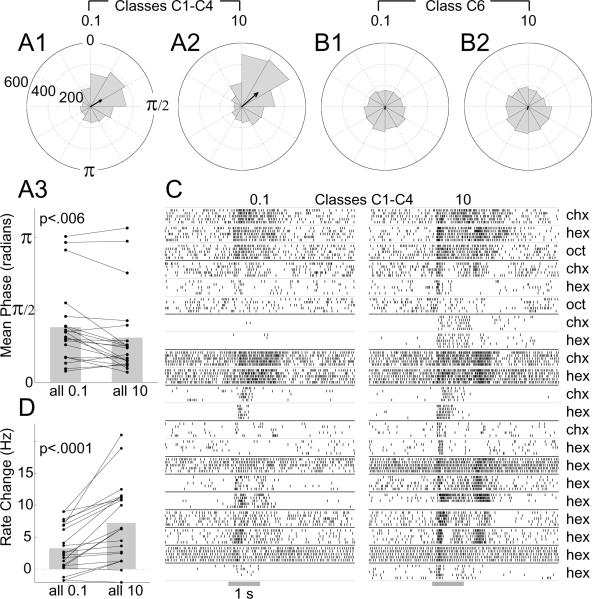

What other functions might the LH serve? Because LHNs are fewer in number than and receive convergent input from PNs, we considered that LHNs might serve, in part, to extract general features of odorants. A computational model has suggested converging input from PNs could cause spikes in LHNs to occur with a phase preference that varied with, and thus contained information about, odor concentration (Assisi et al., 2007). To test this idea experimentally, we measured the phases of spiking relative to the LFP in LHNs that appear to receive convergent input from PNs (classes C1, C2, C3 and C4).

As predicted by the computational model, we found that spike phase indeed advanced in these neurons; that is, spikes arrived earlier in each oscillation cycle as the odor concentration increased (Fig. 5A1,2). These changes, while small in magnitude, were significant and reliable across different cell-odor pairs (Fig. 5A3). In comparison, β-LNs (class C6), which do not appear to receive convergent input from PNs, did not show such phase-specificity across odor concentrations (Fig. 5B). Further, we found significantly more spikes were elicited by higher concentrations of odors in LHN classes C1-C4 (Fig. 5C,D). Thus, unlike their presynaptic partners, the LHNs receiving convergent PN input appear to encode stimulus intensity in their net firing rates as well as in the phases of their spikes.

Figure 5.

Coding odor concentration in C1-C4 LHNs. A: Spike phase positions in C1-C4 LHNs advance with odor concentration, shown by polar histograms of responses to 0.1% (A1) and 10% (A2) odor concentrations (>2200 spikes for each concentration). Arrows show vector average. Note the decrease in phase evoked by the higher concentration. A3: Pairwise comparison of the mean phase for C1-C4 recordings evoked by low and high concentrations (two-tailed paired t-test; n = 21 cell-odor combinations, from 13 cells; see panel C) shows significant differences. B: Phase positions of spikes in β-LNs (class C6, >2200 spikes) show little phase preference; vector average is close to zero. C: Raster plots show responses of the 13 C1-C4 LHNs to both 0.1% and 10% concentrations of various odors. D: Pairwise comparison of the net change in firing rate evoked by high and low concentrations (average firing rate in a 2 s period from odor onset minus the average background firing rate); two-tailed paired t-test, for the same n = 21 cell-odor combinations.

Bilateral integration

The olfactory systems of many animals including humans (but excluding Drosophila; Stocker et al., 1990), consist of two lateralized, separate pathways in the initial stages of processing. In the locust, for example, none of the well-studied olfactory neurons including the olfactory receptor neurons, the local neurons (in the AL), PNs, KCs, β-LNs and GGN cross the midline to innervate neurons on the opposite side of the brain. However, behavioral observations in insects (Martin 1965; Louis et al., 2008) as well as mammals (Rajan et al., 2006, Porter et al., 2007) show bilateral integration of olfactory information helps in tracking odors. Which neurons in the olfactory system could mediate this process?

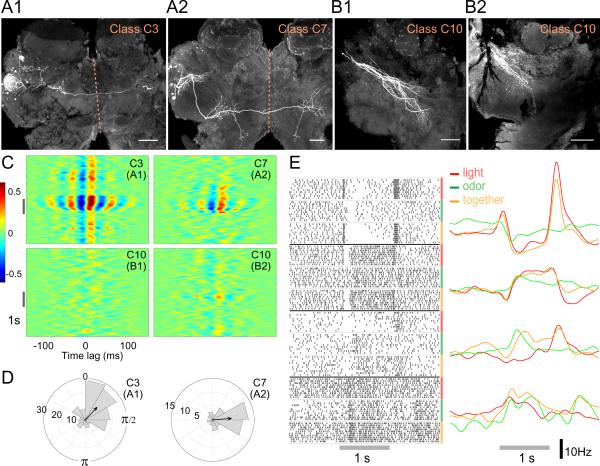

We found that two classes of odor-responsive LHNs in the locust, C3 and C7, extend bilateral projections (Fig. 6A, Fig. 1), suggesting the LH may be the first region in the olfactory hierarchy to mediate bilateral integration. Interestingly, C3 neurons project to the contralateral LH. Spikes recorded in C3 and C7 LHNs showed odor-evoked synchrony (Fig. 6C) and phase-locking with the LFP (Fig. 6D).

Figure 6.

Bilateral and multimodal LHNs. A: Intracellular fills of a C3 and a C7 LHN, showing bilateral projections. Dotted line: midline; scale bar: 100 μm. B: Intracellular fills of 2 C10 multimodal neurons. Cell bodies were not detected. C: Cross-correlograms show that responses of C3 and C7 LHNs correlate well with the LFP, but those of C10 neurons do not. D: Polar histograms show phase-preference of spikes in the C3 and C7 neurons shown in A. E: Responses of 4 multimodal neurons to a light stimulus, an odor stimulus or both stimuli presented together, shown as raster plots (left) and PSTHs (right). All responses shown exceeded the automated response-detection algorithm's significance threshold (see Methods).

Multimodal integration

We asked whether the LH might also mediate integration of olfactory information with other sensory modalities. GGN, despite sending widely sweeping processes throughout the calyx, pedunculus and the α-lobe of the MB (Fig. 1 and 2D,E), did not respond to light or sound in any of our recordings (data not shown). However, 12 other neurons in our sample responded to both odors and light (4 examples are shown in Fig. 6E); their responses were validated with the automated response-detection algorithm (see Methods). These multimodal responses contained varied patterns of excitation and inhibition (Fig. 6E). Two of these neurons could be morphologically identified (class C10) by intracellular fills (Fig. 6B). They showed sparse projections in the ball-like region of LH associated with PN output (compare to classes C1-C4 in Fig. 1), suggesting these multimodal cells may receive their olfactory input from higher-order cells in the region, possibly other LHNs. None of the multimodal cells we identified showed synchrony with the LFP (Fig. 6C, Fig. 4A4).

Discussion

Compared to the well-studied roles of the MB in olfactory coding (Laurent 2002; Masse et al., 2009) and learning (Davis 2011; Keene and Waddell, 2007), the role of the LH in general olfaction remains unclear. We surveyed the LH with electrophysiological and anatomical techniques to evaluate hypotheses about functions this area has been proposed to serve. Our dye-fills of individual LHNs in the locust revealed a surprising diversity of neurons, comprising at least 10 distinct morphological classes (Fig. 1; Table 1).

A class of LHNs, the LHIs, was previously proposed to provide feed-forward inhibition to regulate the firing of KCs based on two sets of observations: intracellular dye-fills showing these LHIs send processes to the MB calyx, and GABA immunostains showing a cluster of ~60 GABAergic neurons in the area of somata of LHIs and a GABAergic fiber tract between the LH and the MB calyx (Perez-Orive et al., 2002). Whether the dye-filled LHIs labeled positively for GABA was not tested.

With dye-fill experiments we identified LHNs matching morphological and physiological descriptions of the LHIs (C1). However, following the same immunostaining technique as the earlier authors, we found these dye-filled neurons were not GABAergic (although we observed strongly-stained GABAergic neurons adjacent to them; Fig. 2A,B). Using this technique we also identified the cluster of GABAergic neurons reported earlier. However, our intracellular fills showed this cluster contained GABA-positive C8 neurons that do not project to the calyx (Fig. 2C). Recent work shows β-LNs with somata near those of the LHIs (Cassenaer and Laurent, 2007) are inhibitory (Cassenaer and Laurent, 2012) suggesting the GABAergic cluster may also contain these β-LNs. We also found that the GABAergic tract between the LH and the MB, thought by the earlier authors to carry feed-forward inhibition from LHIs, is actually a branch of GGN (Fig. 2D). Moreover, we found that most and perhaps all of the GABAergic fibers in the calyx appear to be branches of GGN (Fig. 2E). It remains unknown what functions are served by the LH-branch of GGN. Although a blind-stick sampling procedure cannot definitively rule out the existence of any given neuron, and unknown neurons or neurotransmitters may provide additional inhibitory pathways, neither published observations nor our new results provide evidence that GABAergic LHIs exist, or that any LHNs provide feed-forward inhibition to the KCs.

Our results are consistent with anatomical findings from other insect species. In Drosophila, the anterior paired lateral (APL) neuron, which may contribute to olfactory memory, is the only known GABAergic neuron projecting to the calyx (Liu and Davis, 2009; Pitman et al., 2011; Wu et al, 2011); it is morphologically and physiologically similar to the locust GGN (Papadopoulou et al., 2011), although its influence on KCs remains to be tested. In cockroach (Yamazaki et al., 1998) and honeybee (Bicker et al., 1985) only large GABAergic neurons, with GGN-like connectivity, appear to provide substantial inhibitory input to the calyx. We identified in the moth Manduca sexta a single cluster of GABAergic cells that arborizes in the calyx and the lobe areas of the MB (data not shown; see also Homberg et al., 1987).

Periodic phase-locked inhibition from LHIs was proposed to help the KCs function as coincidence-detectors (Perez-Orive et al., 2002). This idea has also influenced thinking about the role of inhibition in the mammalian cortex (Poo and Isaacson, 2009; Stokes and Isaacson, 2010; Larimer and Strowbridge, 2008). We found that the graded output of GGN is tightly phase-locked to the olfactory system's oscillatory cycle with a phase-lag suitable for defining an input integration window in KCs within each cycle (Fig. 3A,B,C). Thus, although GGN differs from the presumed LHIs in its population size (1 versus 60), output properties (graded versus spiking) and the mechanism of inhibition (feed-back versus feed-forward), it may also promote coincidence-detection in the KCs by imposing brief, stable integration windows in each oscillatory cycle (Fig. 3D). Our results are consistent with the finding of Perez-Orive et al. (2002) that infusing a GABA receptor-blocker to the MB reduces the specificity of olfactory responses in the KCs; our results suggest the source of GABA is GGN rather than the LHIs. Other factors are also thought to contribute to the sparseness of KCs, including their high firing thresholds and specialized nonlinear membrane conductances (Perez-Orive et al., 2002; Perez-Orive et al., 2004; Turner et al., 2008; Demmer and Kloppenburg, 2009). A theoretical model suggested that adaptive regulation of the strength of the PN-KC synapse could also help maintain this sparseness (Finelli et al., 2008).

Increasing concentrations of odors elicit increasingly coincident spiking across PNs, yet the odor-elicited responses of KCs remain sparse across a broad range of odor concentrations (Stopfer et al., 2003). A computational model suggested GABAergic LHIs could help maintain this sparseness by advancing the spiking phase of feed-forward inhibition they provide to KCs as the odor concentration increases (Assisi et al., 2007). Could GGN instead play this role? We found the output phase of GGN remains invariant with concentration, ruling out this mechanism (Fig. 3E). However, GGN appears able to offset increasingly coincident input from PNs in a different way: it counters increasing firing in KCs by feeding back to them stronger inhibition (Fig. 3F; Papadopoulou et al., 2011). Because strong IPSPs rise faster than weak ones, rhythmic inhibition from GGN could regulate the duration of integration windows.

Neurons of the LH have been proposed to mediate specific responses to odorants that are innately meaningful to the animal (Heimbeck et al., 2001; Jefferis et al., 2007). Some LHNs in Drosophila express sex-specific transcripts of the fruitless gene implicated in courtship behaviors (Yu et al., 2010). Further, recent physiological work identified a cluster of neurons in the LH that responded only to the pheromone cVA (Datta et al. 2008; Ruta et al., 2010). These results suggest pheromones, and possibly other odors involved in sexual behaviors (Grosjean et al., 2011), may be processed by specifically-tuned subpopulations of LHNs (Jefferis et al., 2007; Touhara and Vosshall, 2009; Yamagata and Mizunami, 2010). Whether the LH also provides specialized pathways for specific odors processed by the general (non-pheromonal) olfactory system has been unclear. In Drosophila, some anatomical evidence suggested stereotypy and clustering in the projections of genetically labeled PNs in the LH (Tanaka et al., 2004; Jefferis et al., 2007; Lin et al., 2007; Kazama and Wilson, 2009), but whether dendrites of LHNs are restricted to these clusters remains controversial (Tanaka et al., 2004; Jefferis et al., 2007). Nevertheless, the LH, in general, is thought to mediate very specific responses to odors (Luo et al., 2010). Surprisingly, we found in locust that all LHNs we tested (classes C1-C10) responded to all odors. Our anatomical and electrophysiological results show dense convergence of PNs converge onto LHNs (Fig. 4), providing no support for the idea that LHNs, in general, contribute to a labeled-line-like coding of innate preferences for specific odors in the general olfactory system. It remains possible the LH could mediate innate behaviors through specifically-tuned neurons we did not observe, or by responding preferentially to categories of odors we did not test, or through another mechanism, such as the combinatorial coding scheme used by PNs (Laurent, 2002).

The great diversity of LHNs we observed suggests the LH may perform other sensory functions, though. Our observations lead us to speculate about three possible roles: representing general odor properties such as intensity (Fig. 5); beginning bilateral olfactory integration (Fig. 6A); and participating in multimodal integration (Fig. 6B,E). These possible functions could all contribute to unlearned olfactory tasks such as odor-tracking. Hopfield (1995) proposed that phase-coding may allow extremely fast decoding of stimulus intensity by downstream cells. Class C3 neurons, which contain information about the odor concentration in their spike-phases (Fig. 5A) and show bilateral projections (Fig. 6A1), could assist in bilateral integration in the locust by allowing rapid comparison of odor intensity across the midline, a feature potentially important for odor-tracking in some animals (Martin, 1965; Rajan et al., 2006).

Previous work in Drosophila identified neurons connecting the LH with different parts of the brain, including those serving other senses (Tanaka et al., 2004; Tanaka et al., 2008; Jefferis et al., 2007; Ruta et al., 2010). We found several neurons that responded to both visual and olfactory stimuli (Fig. 6E), providing direct evidence for multimodal responses in the LH. Behavioral studies have shown that visual input contributes to odor-tracking (Frye et al., 2003). Thus, in addition to possibly integrating input from the two antennae, neurons of the LH may mediate integration of olfactory and visual cues for odor-tracking behaviors in insects (Duistermars and Frye, 2010). Our results provide specific neuronal targets, from the variety of LHN classes, for further investigation into mechanisms underlying odor-tracking. If the term “innate behaviors” can be used broadly to encompass all memory-independent behaviors such as odor-tracking regardless of odor identity, our results support the role of LH in these behaviors.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sarah Kim and Joby Joseph for their help in developing the project; Diana Cummings and Leonardo Belluscio for antibodies; Collins Assisi, Maxim Bazhenov, Evan Butler, Paolo Forni, Sachiko Murase, Annalisa Scimemi, and members of the Stopfer laboratory for helpful discussions. We also thank Kui Sun for her excellent animal care. Microscopy was performed at the Microscopy & Imaging Core (NICHD) with the kind assistance of Vincent Schram and Louis Dye. This work was supported by an intramural grant from NIH-NICHD to M.S.

References

- Assisi C, Stopfer M, Laurent G, Bazhenov M. Adaptive regulation of sparseness by feedforward inhibition. Nature Neuroscience. 2007;10:1176–1184. doi: 10.1038/nn1947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bicker G, Schäfer S, Kingan TG. Mushroom body feedback interneurones in the honeybee show GABA-like immunoreactivity. Brain Research. 1985;360:394–397. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)91262-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SL, Joseph J, Stopfer M. Encoding a temporally structured stimulus with a temporally structured neural representation. Nature Neuroscience. 2005;8:1568–1576. doi: 10.1038/nn1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey AF, Carlson JR. Insect olfaction from model systems to disease control. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:12987–12995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103472108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassenaer S, Laurent G. Hebbian STDP in mushroom bodies facilitates the synchronous flow of olfactory information in locusts. Nature. 2007;448:709–713. doi: 10.1038/nature05973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassenaer S, Laurent G. Conditional modulation of spike-timing-dependent plasticity for olfactory learning. Nature. 2012;482:47–52. doi: 10.1038/nature10776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly KC, Durtschi ML, Smith BH. Olfactory-based discrimination learning in the moth, Manduca sexta. Journal of Insect Physiology. 2001;47:375–384. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1910(00)00117-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta SR, Vasconcelos ML, Ruta V, Luo S, Wong A, Demir E, Flores J, Balonze K, Dickson BJ, Axel R. The Drosophila pheromone cVA activates a sexually dimorphic neural circuit. Nature. 2008;452:473–477. doi: 10.1038/nature06808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis RL. Traces of Drosophila memory. Neuron. 2011;70:8–19. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Belle JS, Heisenberg M. Associative odor learning in Drosophila abolished by chemical ablation of mushroom bodies. Science. 1994;263:692–695. doi: 10.1126/science.8303280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demmer H, Kloppenburg P. Intrinsic membrane properties and inhibitory synaptic input of kenyon cells as mechanisms for sparse coding? Journal of Neurophysiology. 2009;102:1538–1550. doi: 10.1152/jn.00183.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duistermars BJ, Frye MA. Multisensory integration for odor tracking by flying Drosophila: Behavior, circuits and speculation. Communicative & Integrative Biology. 2010;3:60–63. doi: 10.4161/cib.3.1.10076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst KD, Boeckh J, Boeckh V. A neuroanatomical study on the organization of the central antennal pathways in insects. Cell and Tissue Research. 1977;176:285–308. doi: 10.1007/BF00221789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finelli LA, Haney S, Bazhenov M, Stopfer M, Sejnowski TJ. Synaptic learning rules and sparse coding in a model sensory system. PLoS Computational Biology. 2008;4:e1000062. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye MA, Tarsitano M, Dickinson MH. Odor localization requires visual feedback during free flight in Drosophila melanogaster. The Journal of Experimental Biology. 2003;206:843–855. doi: 10.1242/jeb.00175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosjean Y, Rytz R, Farine J-P, Abuin L, Cortot J, Jefferis GSXE, Benton R. An olfactory receptor for food-derived odours promotes male courtship in Drosophila. Nature. 2011;478:236–240. doi: 10.1038/nature10428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansson BS, editor. Insect Olfaction. Springer-Verlag; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Heimbeck G, Bugnon V, Gendre N, Keller A, Stocker RF. A central neural circuit for experience-independent olfactory and courtship behavior in Drosophila melanogaster. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98:15336–15341. doi: 10.1073/pnas.011314898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homberg U, Christensen TA, Hildebrand JG. Structure and function of the deutocerebrum in insects. Annual Review of Entomology. 1989;34:477–501. doi: 10.1146/annurev.en.34.010189.002401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homberg U, Kingan TG, Hildebrand JG. Immunocytochemistry of GABA in the brain and suboesophageal ganglion of Manduca sexta. Cell and Tissue Research. 1987;248:1–24. doi: 10.1007/BF01239957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honegger KS, Campbell RAA, Turner GC. Cellular-resolution population imaging reveals robust sparse coding in the Drosophila mushroom body. Journal of Neuroscience. 2011;31:11772–11785. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1099-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopfield JJ. Pattern recognition computation using action potential timing for stimulus representation. Nature. 1995;376:33–36. doi: 10.1038/376033a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito I, Ong RC-Y, Raman B, Stopfer M. Sparse odor representation and olfactory learning. Nature Neuroscience. 2008;11:1177–1184. doi: 10.1038/nn.2192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferis GSXE, Potter CJ, Chan AM, Marin EC, Rohlfing T, Maurer CR, Luo L. Comprehensive maps of Drosophila higher olfactory centers: spatially segregated fruit and pheromone representation. Cell. 2007;128:1187–1203. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jortner RA, Farivar SS, Laurent G. A simple connectivity scheme for sparse coding in an olfactory system. Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27:1659–1669. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4171-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazama H, Wilson RI. Origins of correlated activity in an olfactory circuit. Nature Neuroscience. 2009;12:1136–1144. doi: 10.1038/nn.2376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keene AC, Waddell S. Drosophila olfactory memory: single genes to complex neural circuits. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2007;8:341–354. doi: 10.1038/nrn2098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kido A, Ito K. Mushroom bodies are not required for courtship behavior by normal and sexually mosaic Drosophila. Journal of Neurobiology. 2002;52:302–311. doi: 10.1002/neu.10100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer P, Strowbridge BW. Nonrandom local circuits in the dentate gyrus. Journal of Neuroscience. 2008;28:12212–12223. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3612-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurent G. Olfactory network dynamics and the coding of multidimensional signals. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2002;3:884–895. doi: 10.1038/nrn964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurent G, Naraghi M. Odorant-induced oscillations in the mushroom bodies of the locust. Journal of Neuroscience. 1994;14:2993–3004. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-05-02993.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitch B, Laurent G. GABAergic synapses in the antennal lobe and mushroom body of the locust olfactory system. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1996;372:487–514. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960902)372:4<487::AID-CNE1>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H-H, Lai JS-Y, Chin A-L, Chen Y-C, Chiang A-S. A map of olfactory representation in the Drosophila mushroom body. Cell. 2007;128:1205–1217. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Davis RL. The GABAergic anterior paired lateral neuron suppresses and is suppressed by olfactory learning. Nature Neuroscience. 2009;12:53–59. doi: 10.1038/nn.2235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louis M, Huber T, Benton R, Sakmar TP, Vosshall LB. Bilateral olfactory sensory input enhances chemotaxis behavior. Nature Neuroscience. 2008;11:187–199. doi: 10.1038/nn2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo SX, Axel R, Abbott LF. Generating sparse and selective third-order responses in the olfactory system of the fly. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:10713–10718. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005635107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod K, Bäcker A, Laurent G. Who reads temporal information contained across synchronized and oscillatory spike trains? Nature. 1998;395:693–698. doi: 10.1038/27201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin EC, Jefferis GSXE, Komiyama T, Zhu H, Luo L. Representation of the glomerular olfactory map in the Drosophila brain. Cell. 2002;109:243–255. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00700-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin H. Osmotropotaxis in the honey-bee. Nature. 1965;208:59–63. [Google Scholar]

- Masse NY, Turner GC, Jefferis GSXE. Olfactory information processing in Drosophila. Current Biology. 2009;19:R700–R713. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulou M, Cassenaer S, Nowotny T, Laurent G. Normalization for sparse encoding of odors by a wide-field interneuron. Science. 2011;332:721–725. doi: 10.1126/science.1201835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Orive J, Bazhenov M, Laurent G. Intrinsic and circuit properties favor coincidence detection for decoding oscillatory input. Journal of Neuroscience. 2004;24:6037–6047. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1084-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Orive J, Mazor O, Turner GC, Cassenaer S, Wilson RI, Laurent G. Oscillations and sparsening of odor representations in the mushroom body. Science. 2002;297:359–365. doi: 10.1126/science.1070502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitman JL, Huetteroth W, Burke CJ, Krashes MJ, Lai S-L, Lee T, Waddell S. A Pair of inhibitory neurons are required to sustain labile memory in the Drosophila mushroom body. Current Biology. 2011;21:855–861. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.03.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poo C, Isaacson JS. Odor representations in olfactory cortex: “sparse” coding, global inhibition, and oscillations. Neuron. 2009;62:850–861. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter J, Craven B, Khan RM, Chang S-J, Kang I, Judkewitz B, Judkewicz B, Volpe J, Settles G, Sobel N. Mechanisms of scent-tracking in humans. Nature Neuroscience. 2007;10:27–29. doi: 10.1038/nn1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajan R, Clement JP, Bhalla US. Rats smell in stereo. Science. 2006;311:666–670. doi: 10.1126/science.1122096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruta V, Datta SR, Vasconcelos ML, Freeland J, Looger LL, Axel R. A dimorphic pheromone circuit in Drosophila from sensory input to descending output. Nature. 2010;468:686–690. doi: 10.1038/nature09554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stocker RF, Lienhard MC, Borst A, Fischbach KF. Neuronal architecture of the antennal lobe in Drosophila melanogaster. Cell and Tissue Research. 1990;262:9–34. doi: 10.1007/BF00327741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokes CCA, Isaacson JS. From dendrite to soma: Dynamic routing of inhibition by complementary interneuron microcircuits in olfactory cortex. Neuron. 2010;67:452–465. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stopfer M, Jayaraman V, Laurent G. Intensity versus identity coding in an olfactory system. Neuron. 2003;39:991–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2003.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stopfer M, Laurent G. Short-term memory in olfactory network dynamics. Nature. 1999;402:664–668. doi: 10.1038/45244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka NK, Awasaki T, Shimada T, Ito K. Integration of chemosensory pathways in the Drosophila second-order olfactory centers. Current Biology. 2004;14:449–457. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka NK, Tanimoto H, Ito K. Neuronal assemblies of the Drosophila mushroom body. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2008;508:711–755. doi: 10.1002/cne.21692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touhara K, Vosshall LB. Sensing odorants and pheromones with chemosensory receptors. Annual Review of Physiology. 2009;71:307–332. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.010908.163209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner GC, Bazhenov M, Laurent G. Olfactory representations by Drosophila mushroom body neurons. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2008;99:734–746. doi: 10.1152/jn.01283.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vickers N, Baker T. Latencies of behavioral response to interception of filaments of sex pheromone and clean air influence flight track shape in Heliothis virescens (F.) males. J Comp Physiol A. 1996;178:831–847. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Chiang A-S, Xia S, Kitamoto T, Tully T, Zhong Y. Blockade of neurotransmission in Drosophila mushroom bodies impairs odor attraction, but not repulsion. Current Biology. 2003;13:1900–1904. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehr M, Laurent G. Odour encoding by temporal sequences of firing in oscillating neural assemblies. Nature. 1996;384:162–166. doi: 10.1038/384162a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong AM, Wang JW, Axel R. Spatial representation of the glomerular map in the Drosophila protocerebrum. Cell. 2002;109:229–241. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00707-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C-L, Shih M-FM, Lai JS-Y, Yang H-T, Turner GC, Chen L, Chiang A-S. Heterotypic gap junctions between two neurons in the drosophila brain are critical for memory. Current Biology. 2011;21:848–854. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia S, Tully T. Segregation of odor identity and intensity during odor discrimination in Drosophila mushroom body. PLoS Biology. 2007;5:e264. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamagata N, Mizunami M. Spatial representation of alarm pheromone information in a secondary olfactory centre in the ant brain. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2010;277:2465–2474. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2010.0366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki Y, Nishikawa M, Mizunami M. Three classes of GABA-like immunoreactive neurons in the mushroom body of the cockroach. Brain Research. 1998;788:80–86. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)01515-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu JY, Kanai MI, Demir E, Jefferis GSXE, Dickson BJ. Cellular organization of the neural circuit that drives Drosophila courtship behavior. Current Biology. 2010;20:1602–1614. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]