Abstract

Background

Numerous functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies of the brain-bases of autism have demonstrated altered cortical responses in subjects with autism, relative to typical subjects, during a variety of tasks. These differences may reflect altered neuronal responses or altered hemodynamic response. This study searches for evidence of hemodynamic response differences by using a simple visual stimulus and elementary motor actions, which should elicit similar neuronal responses in patients and controls.

Methods

We acquired fMRI data from two groups of 16 children, a typical group and a group with Simplex Autism, during a simple visuomotor paradigm previously used to assess this question in other cross-group comparisons. A general linear model estimated the blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) signal time course, and repeated-measures analysis of variance tested for potential cross-group differences in the BOLD signal.

Results

The hemodynamic response in Simplex Autism is similar to that found in typical children. Although the sample size was small for a secondary analysis, medication appeared to have no effect on the hemodynamic response within the Simplex Autism group.

Conclusions

When fMRI studies show BOLD response differences between autistic and typical subjects, these results likely reflect between-group differences in neural activity and not an altered hemodynamic response.

Keywords: functional magnetic resonance imaging, visuomotor, autism spectrum disorders, event-related, neurovascular coupling, medication effects

1. Introduction

Fluctuations in the blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) signal have been shown to couple tightly with neural activity (Logothetis, et al. 2001). Thus, functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) and functional connectivity MRI (fcMRI) can be used as indirect measures of neural activity. However, atypical subjects, such as children with ASD (Autistic Spectrum Disorders), may have a quantitatively different relationship between the blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) signal, which is measured by fMRI, and neuronal responses, i.e. different neurovascular coupling.

This is important because recent fMRI studies (e.g., (Mostofsky, et al. 2009; Muller, et al. 2003)) have shown differences in the BOLD signal for motor, parietal, cerebellar, and prefrontal cortical regions of the brain during complex visuomotor tasks. Further, recent fcMRI studies have reported under-connectivity between anterior and posterior regions of the brain (e.g., (Cherkassky, et al. 2006)); aberrant connectivity in frontal, parietal, and occipital regions of the brain (e.g.,(Noonan, et al. 2009)); and reduced long range functional connection between regions of the brain comprising the default-mode network (e.g.,(Kennedy and Courchesne 2008; Monk, et al. 2009; Weng, et al. 2010)).

fMRI and fcMRI comparisons of ASD and typical subjects typically assume a hemodynamic response time course that, independent of differences in neural activity, is the same between ASD and typical subjects (e.g., (Gomot, et al. 2008; Kaiser, et al. 2010)). However, little data exist to show that the hemodynamic response is generally similar between people with and without ASD. In order to interpret properly the current autism fMRI literature, it is important to demonstrate that the basic hemodynamic response is similar between ASD and typical cohorts at typical sample sizes. A key first step would be to examine the hemodynamic response of people with and without ASD during a simple task, where the demands of the task are not likely to be affected by an ASD diagnosis (Church, et al. 2011, Church et al in press; Harris, et al. 2011). The value of this step is predicated on the assumption that the two cohorts would perform the task the same way and have similar neuronal activity that could then be measured by fMRI. The limitations to this assumption are discussed in the Discussion section.

We compared the temporal dynamics of the BOLD signal between children with and without Simplex Autism (defined below) during a simple visuomotor task (Miezin, et al. 2000) in which we would expect no significant differences in the underlying neural activity. The same paradigm has been used to test the hypothesis that typical adults and children have the same fundamental relationship between neural activity and the BOLD signal (Kang, et al. 2003). If similar BOLD time courses are observed in multiple vascular distributions when the task is sufficiently simple that neuronal processing is expected to be equivalent in autistic and control children, then differences in BOLD time courses that are observed in fMRI autism studies of similar sample sizes more likely reflect differences in neural activity than differences in the hemodynamic response.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Participants

Simplex Autism refers to well-characterized ASD individuals with no affected first-degree relatives. Sixteen typical and 16 Simplex Autism children (ages 9 –14 years) were recruited using a variety of means, including recruitment from the local community through flyers and advertisements, and through other research collaborations. Demographics are shown in Table 1. Subjects were screened out for a history of focal neurological deficit, strabismus, or vision not corrected to normal acuity with glasses. All subjects (typical and ASD) had no first-degree relatives with an ASD. In addition, typical children could not have any first-degree relatives with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). Simplex Autism participants had 1) community MD or PhD clinical diagnoses of Autistic Disorder, Asperger’s Disorder, or Pervasive Developmental Disorder Not Otherwise Specified (PDD-NOS), and 2) consensus research ASD diagnoses as measured by the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (Lord, et al. 2000) and Autism Diagnostic Interview Revised (Lord, et al. 1994). Five typical and two Simplex Autism subjects were assessed in previous studies using the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC-IV). The other children were assessed using the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI). All children performed the vocabulary subtest of the corresponding assessment, and all but one typical child performed the block design subtest of the corresponding assessment. Informed consent and assent were obtained using procedures approved by the Washington University Human Research Protection Office.

Table 1.

Demographics

| Simplex Autism Subjects | Typical Subjects | |

|---|---|---|

| Male/female | 13m/3f | 13m/3f |

| Age | 11.9 ± 1.89 | 12.6 ± 1.80 |

| IQ | 104.9 ± 12.97 | 115.7 ± 10.64 |

| Vocabulary scaled score | 10.25 ± 3.26 | 13.00 ± 2.37 |

| Block design scaled score | 10.88 ± 3.05 | 12.23 ± 2.12 |

| SRS | 102 ± 21.7 | 17.8 ± 9.56 |

| Medicated/Un-medicated | 8/8 | 0/16 |

Demographics of participants included in the fMRI study. Psychotropic medications included selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, psychostimulants, and antipsychotic medications. Independent samples T-tests were conducted to determine whether the groups were significantly different on age, intelligence quotient (IQ), the vocabulary and block design scaled scores, and the Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS), a quantitative measure of autistic traits. While age was not significantly different between Simplex Autism and typical cohorts (P = 0.28), IQ was significantly greater for the typical than the Simplex Autism cohort (P = 0.016). SRS was significantly greater for the Simplex Autism than the typical cohort (P < 0.0001). The vocabulary (P = 0.019) but not block design (P = 0.15) subscale score was significantly greater in the typical cohort. One typical subject did not perform the block design subtest, and was not included in the T-test comparison.

2.2 MRI protocols

MRI data were acquired using a Siemens 3T Trio scanner (Erlangen, Germany) with standard 12-channel head coil. An iMac Macintosh computer (Apple, Cupertino, CA) running Psyscope X software (Cohen, et al. 1993) was used to control the stimulus display. Responses were recorded using a fiberoptic key-press device held in the subject’s hands. An LCD projector was used to project stimuli onto a screen at the head of the bore. Subjects viewed the stimuli through a mirror attached to the head coil.

High-resolution structural images were acquired using a sagittal MP-RAGE T1 weighted sequence (TE=3.08ms, TR = 2.4s, TI = 1000ms, flip angle = 8°, 176 slices at 1 mm isotropic resolution/voxel). Functional images were acquired using a BOLD contrast sensitive, gradient echo, echo-planar sequence (TE= 27ms, flip angle = 90°, 4×4×4 mm isotropic resolution/voxel). MR acquisition was 2.5 seconds/frame and consisted of 32 contiguous, axial slices, centered on the hemispheric divide and parallel to the AC-PC plane. The first four frames in each run were discarded to allow stabilization of longitudinal magnetization. Each functional run lasted approximately three minutes (72 frames). Four runs were acquired per subject.

2.3 Behavioral paradigm

The task, a jittered event-related design known to generate highly reproducible activation in sensorimotor and visual cortex for both adults and children, has been described in detail previously (Kang, et al. 2003; Miezin, et al. 2000). Briefly, subjects pressed a button at the onset and offset of a visual stimulus presented for 1.26 seconds. The visual stimulus was a radial counterphase-flickering checkerboard subtending ~11° of the visual field surrounding the fovea. Right and left index fingers were used for onset and offset respectively. Approximately 30 stimulus presentations appeared per 72-frame run. Accuracy, measured as a percentage of onset and offset omissions, and median reaction time (RT) per subject were evaluated using two-sample two-tailed t-tests.

2.4 fMRI data analysis

BOLD data from each subject were pre-processed to remove noise and artifacts (Kang, et al. 2003; Miezin, et al. 2000). Head motion per BOLD run was quantified using total root mean square (RMS) linear and angular displacement measures. For the main analysis, and in order to match the amount of head movement between the two cohorts, two of the four runs per subject were chosen, so that average total RMS head movement was not significantly different between the two groups. The total RMS is derived from measurements in six directions relative to the first frame acquired across each run. We attempted to match best this total RMS between each typical and each ASD subject. As a result, we did not control for the order of the runs. Results were primarily analyzed from these motion-matched, selected pairs of runs. In addition, as a secondary analysis, results from each individual run and the combined set of four BOLD runs regardless of motion difference across groups were analyzed.

An anatomical average of each subject’s cross-aligned BOLD data was registered to his/her MP-RAGE. Spatial normalization was performed using a 12-parameter affine warping of the individual MP-RAGE images to an atlas-representative target as described previously (Kang, et al. 2003; Snyder 1996). The atlas-representative target itself was constructed by 12-parameter affine co-registration of a group of MP-RAGE images representing two groups of 13 young children (ages 7–9) and 12 young adults (ages 21–30). To measure the accuracy of atlas transformations, Eta (η) values were derived from the correlation of similarity between the atlas and the morphed MP-RAGE images (Snyder 1996). η2 is the measure of variance in the source image that is accounted for by variance in the target image (Kang, et al. 2003).

To investigate putative differences in the shape of the BOLD time course in Simplex Autism, no assumptions were made about its underlying shape. Preprocessed data were smoothed using a 2 mm full-width half-max kernel, and analyzed using an implementation of the general linear model (GLM). Both a constant offset and a linear trend terms were included in the GLM for each BOLD run. Seven time points (1 TR/MR frame = 2.5s apart) for each stimulus trial were modeled in the GLM. Significant differences between the two cohorts were tested using a voxelwise group by time course (2 groups × 7 MR frames), sphericity corrected, repeated measures ANOVA (Kang, et al. 2003; Miezin, et al. 2000), which accounts for correlations in the design (Ollinger, et al. 2001a; Ollinger, et al. 2001b). The statistical maps were corrected for multiple comparisons using the Monte Carlo method (to achieve significance with P < 0.05, 24 contiguous voxels with a Z score > 3.5 are needed) (Kang, et al. 2003; McAvoy, et al. 2001). In-house software, (FIDL), was used to perform these analyses. Activated regions were identified in the statistical map generated from the main effect of time course. Effects of diagnosis were examined using the group by time course interaction statistical map. The group by time course interaction measures shape differences between the BOLD signals from the two cohorts. As alluded to above, five additional group by time repeated measures ANOVAs were performed to confirm the lack of a significant group by time interaction: one ANOVA combining all four runs per subject, and one ANOVA for each individual run per subject.

To assess potential differences further, ROIs were delineated from the main effect of time course map via a peak-finding algorithm as described elsewhere (Kang, et al. 2003; Miezin, et al. 2000). Time courses, averaged over the activated voxels, were derived per ROI and subject. Time courses for each ROI were entered into a group by time repeated measures ANOVA for subsequent analysis.

3. Results

Behavioral performance was examined in terms of both accuracy and RT. No differences in onset (T30 = 1.197, P = 0.241) and offset (T17.057 = −1.630, P = 0.121) RTs were observed between Simplex Autism and typical cohorts. No significant differences were found between Simplex Autism and typical cohorts for onset and offset omissions (all P > 0.09). Omissions and incorrect responses represented less than 6% of all trials per subject.

3.1 Primary analysis: two runs per subject matched for differences in motion between Simplex Autism and typical cohorts

For the primary analysis, where two runs per subject were chosen in order to control for head movement, no significant differences in head movement were observed between the Simplex Autism and typical children (T30 = 0.482, P = 0.633). Mean RMS values for each group were under 1 mm (0.57 mm for Simplex Autism, 0.51 mm for typical). Mean η2 values were similar between Simplex Autism (0.9902) and typical (0.9909) groups, and means were not statistically different (T21.98 = 1.734, P = .097).

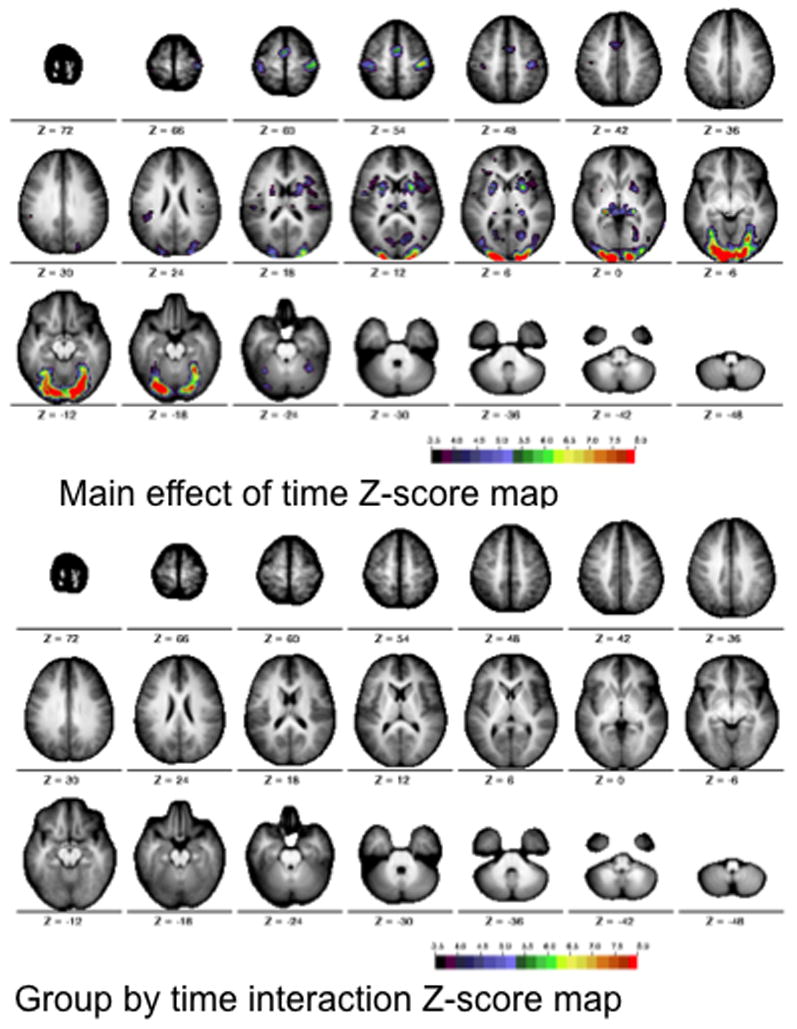

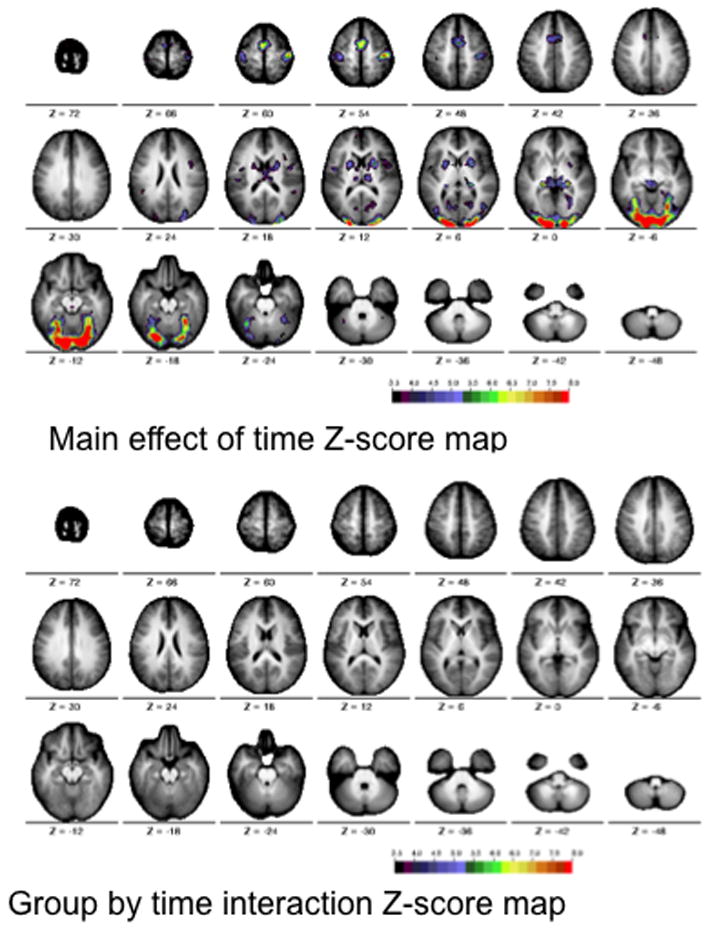

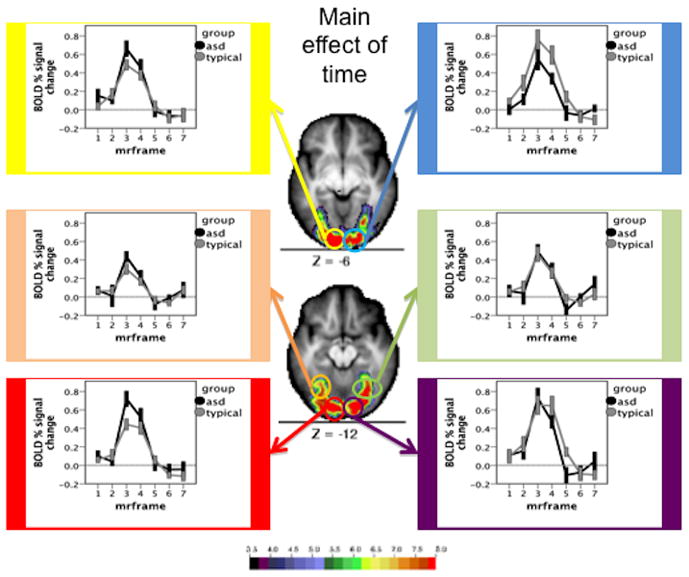

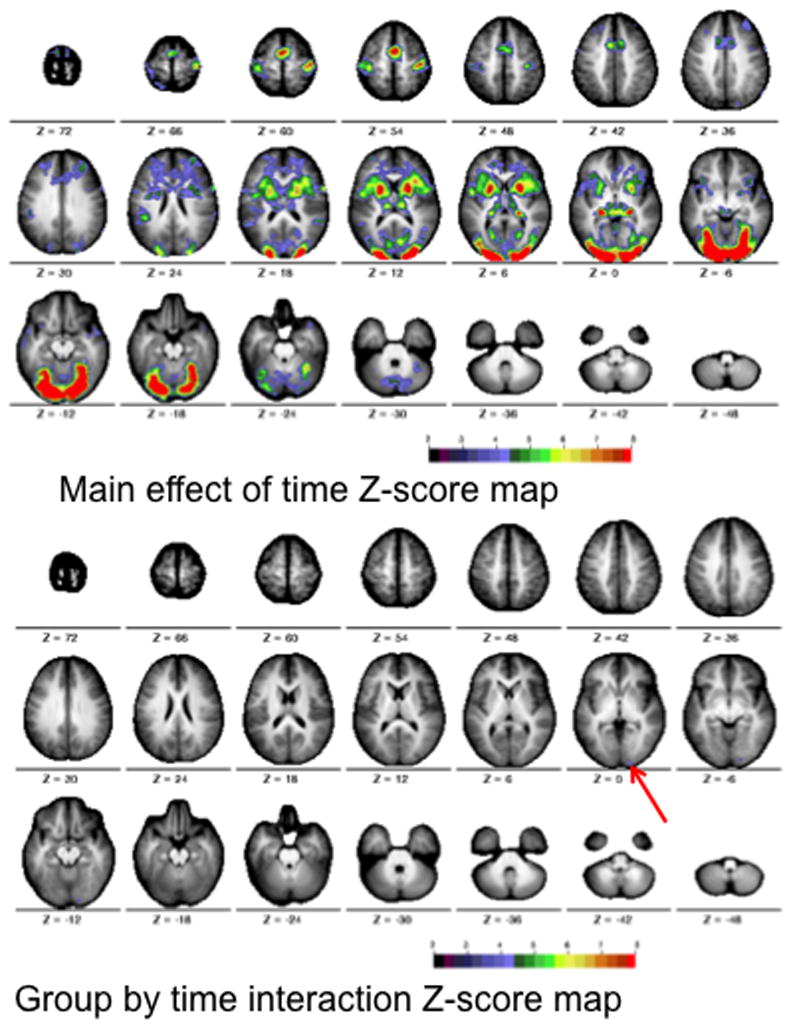

After correcting for multiple comparisons, the voxelwise ANOVA revealed significant main effects of time course (Figure 1a, top), but no group by time course interactions (Figure 1a, bottom). A subset of participants (12 Simplex Autism and 12 typical participants), matched for both motion (P = 0.33) and full-scale IQ (Simplex Autism FSIQ = 111 +/− 8, typical FSIQ = 113 +/− 9, P = 0.53), were also examined to ensure that IQ differences did not mask any group by time interactions. Matching for IQ revealed no Monte-Carlo corrected significant group by time course interactions (Figure 1b, bottom).

Figure 1.

Figure 1a. Statistical maps for the motion matched scans across the two groups (cohorts). The images show the Z score maps for the main effect of time course (top) and the interaction of time course by group (bottom). The statistical maps are corrected for multiple comparisons using the Monte Carlo method. The colors on the map represent Z scores from 3.5 (black) to 8 (red).

Figure 1b. Statistical maps for motion and IQ matched scans across the two groups (cohorts). The images show the Z score maps for the main effect of time course (top) and the interaction of time course by group (bottom). The statistical maps are corrected for multiple comparisons using the Monte Carlo method. The colors on the map represent Z scores from 3.5 (black) to 8 (red).

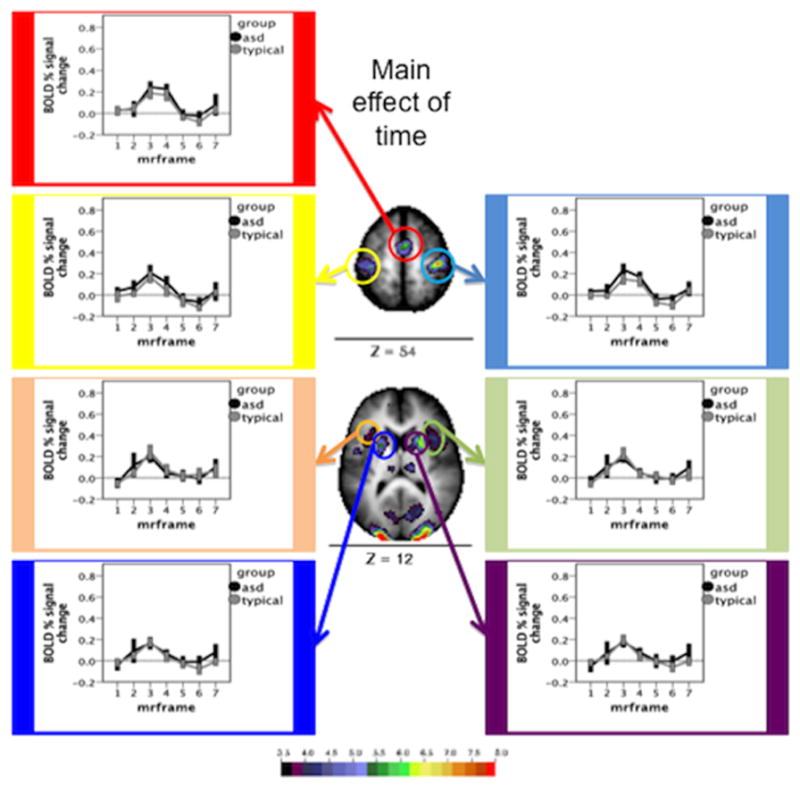

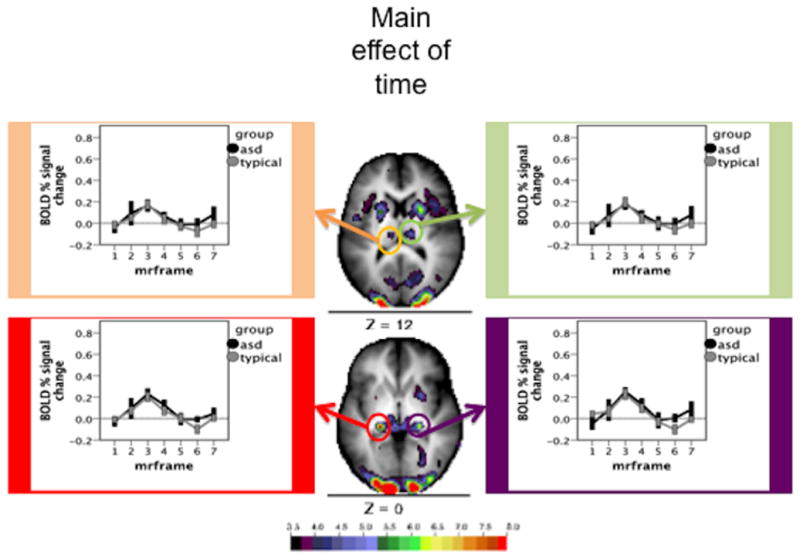

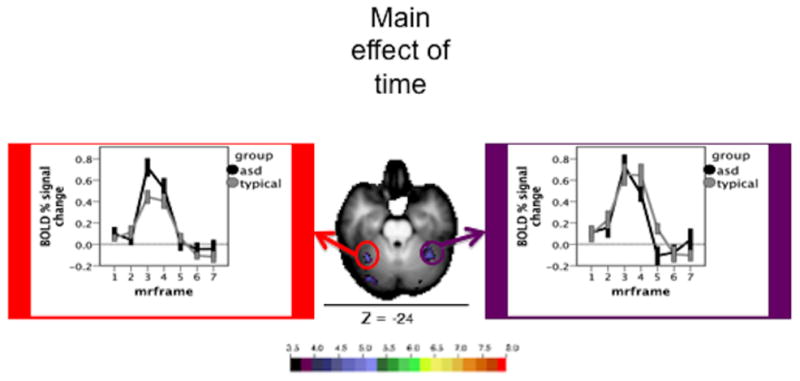

Using a peak-finding algorithm, 67 ROIs were found that showed significant time courses in the main effect analysis. Of these 67 ROIs, 19 were chosen to sample varying vascular distributions. Average time courses were computed for the 19 delineated ROIs for Simplex Autism and typical cohorts. Figure 2 shows time courses for regions fed by anterior and middle cerebral arteries. Figure 3 shows time courses for regions fed by the perforating branches from the posterior cerebral artery. Figure 4 shows time courses for regions fed by the posterior cerebral artery. Figure 5 shows time courses for regions fed by the superior cerebellar artery. The individual time courses were entered into group by time repeated measures ANOVAs for subsequent analyses (Table 2: motion matched subjects; Table 3: motion and IQ matched). No significant diagnosis by time course interaction effects were found (all P values > 0.1).

Figure 2.

Time courses and Monte Carlo corrected statistical Z-map for regions served by the anterior cerebral and middle cerebral arteries. The map depicts the Z statistics derived from the main effect of time course. The mean time courses for Simplex Autism (dark) and typical (light) cohorts are depicted for each of the chosen ROIs. Error bars represent 1 standard error of the mean. Color bar ranges from black (Z = 3.5) to red (Z = 8).

Figure 3.

Time courses and Monte Carlo corrected statistical Z-map for regions served by the perforating branches from the posterior cerebral artery. The map depicts the Z statistics derived from the main effect of time course. The mean time courses for Simplex Autism (dark) and typical (light) cohorts are depicted for each of the chosen ROIs. Error bars represent 1 standard error of the mean. Color bar ranges from black (Z = 3.5) to red (Z = 8).

Figure 4.

Time courses and Monte Carlo corrected statistical Z-map for regions served by the posterior cerebral artery. The map depicts the Z statistics derived from the main effect of time course. The mean time courses for Simplex Autism (dark) and typical (light) cohorts are depicted for each of the chosen ROIs. Error bars represent 1 standard error of the mean. Color bar ranges from black (Z = 3.5) to red (Z = 8).

Figure 5.

Time courses and Monte Carlo corrected statistical Z-map for regions served by the superior cerebellar artery. The map depicts the Z statistics derived from the main effect of time course. The mean time courses for Simplex Autism (dark) and typical (light) cohorts are depicted for each of the chosen ROIs. Error bars represent 1 standard error of the mean. Color bar ranges from black (Z = 3.5) to red (Z = 8).

TABLE 2.

Time course X group repeated measures ANOVAs

| Region | X | Y | Z | Df | F | P | Partial eta^2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| right motor | 39 | −23 | 55 | 3.86, 115.76 | 0.18 | 0.94 | 0.006 |

| SMA | −1 | −4 | 57 | 3.85,115.53 | 0.17 | 0.95 | 0.005 |

| left motor | −38 | −28 | 59 | 3.75,112.48 | 0.14 | 0.96 | 0.005 |

| right insula | 40 | 8 | 10 | 3.80,114.09 | 0.35 | 0.83 | 0.012 |

| left insula | −38 | 8 | 11 | 3.86,115.65 | 0.36 | 0.83 | 0.012 |

| right putamen | 23 | 4 | 9 | 3.44,103.31 | 0.56 | 0.67 | 0.018 |

| left putamen | −22 | 3 | 9 | 3.16,94.78 | 0.28 | 0.85 | 0.009 |

| right thalamus | 12 | −22 | 11 | 3.81,114.28 | 0.45 | 0.76 | 0.015 |

| left thalamus | −9 | −23 | 12 | 3.58,107.50 | 0.43 | 0.76 | 0.014 |

| right LGN | 19 | −33 | 1 | 3.93,117.89 | 1.08 | 0.37 | 0.035 |

| left LGN | −20 | −31 | 0 | 3.78,113.51 | 0.46 | 0.75 | 0.015 |

| right fusiform | 28 | −71 | −10 | 3.94,118.27 | 0.80 | 0.52 | 0.026 |

| left fusiform | −27 | −65 | −11 | 3.69,110.74 | 0.68 | 0.60 | 0.022 |

| right visual | 19 | −87 | −12 | 3.99,119.71 | 1.52 | 0.20 | 0.048 |

| left visual | −23 | −88 | −12 | 3.75,112.51 | 1.77 | 0.14 | 0.056 |

| right visual | 15 | −96 | −5 | 3.59,107.59 | 2 | 0.11 | 0.063 |

| left visual | −13 | −91 | −9 | 3.98,119.52 | 1.09 | 0.37 | 0.035 |

| right cerebellum | 36 | −51 | −25 | 3.57,107.17 | 0.98 | 0.42 | 0.032 |

| left cerebellum | −32 | −53 | −20 | 3.93,117.99 | 0.59 | 0.67 | 0.019 |

The results from the ROI time course by group repeated measures ANOVAs performed on the selected main-effect ROIs. X, Y, and Z coordinates correspond to the Talairach standard space. Degrees of freedom, F, P, and partial eta squared values are listed for the interaction of group diagnosis and time course.

TABLE 3.

Timecourse X group repeated measures ANOVAs: IQ matched

| Region | X | Y | Z | Df | F | P | Partial eta^2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| right motor | 39 | −23 | 55 | 3.72, 81.9 | 0.57 | 0.67 | 0.025 |

| SMA | −1 | −4 | 57 | 3.82, 84.1 | 0.5 | 0.81 | 0.022 |

| left motor | −38 | −28 | 59 | 3.05, 67.18 | 0.74 | 0.53 | 0.033 |

| right insula | 40 | 8 | 10 | 3.28, 72.14 | 0.82 | 0.5 | 0.036 |

| left insula | −38 | 8 | 11 | 3.3, 72.49 | 0.79 | 0.52 | 0.035 |

| right putamen | 23 | 4 | 9 | 2.96, 65.07 | 0.86 | 0.46 | 0.038 |

| left putamen | −22 | 3 | 9 | 2.75, 60.42 | 0.63 | 0.59 | 0.028 |

| right thalamus | 12 | −22 | 11 | 6, 132 | 0.29 | 0.94 | 0.013 |

| left thalamus | −9 | −23 | 12 | 4.14, 91.08 | 0.17 | 0.96 | 0.008 |

| right LGN | 19 | −33 | 1 | 6, 132 | 1.03 | 0.41 | 0.045 |

| left LGN | −20 | −31 | 0 | 4.49, 98.68 | 1.08 | 0.37 | 0.047 |

| right fusiform | 28 | −71 | −10 | 4.04, 88.94 | 1.41 | 0.24 | 0.06 |

| left fusiform | −27 | −65 | −11 | 4.05, 89.09 | 2.11 | 0.085 | 0.088 |

| right visual | 19 | −87 | −12 | 6, 132 | 1.54 | 0.17 | 0.065 |

| left visual | −23 | −88 | −12 | 3.86, 84.76 | 1.75 | 0.15 | 0.074 |

| right visual | 15 | −96 | −5 | 3.94, 86.65 | 1.49 | 0.21 | 0.063 |

| left visual | −13 | −91 | −9 | 3.89, 85.67 | 1.68 | 0.17 | 0.071 |

| right cerebellum | 36 | −51 | −25 | 6, 132 | 1.43 | 0.21 | 0.061 |

| left cerebellum | −32 | −53 | −20 | 3.66, 80.62 | 0.93 | 0.45 | 0.041 |

The results from the ROI time course by group repeated measures ANOVAs performed on the selected main-effect ROIs, for the IQ matched groups. X, Y, and Z coordinates correspond to the Talairach standard space. Degrees of freedom, F, P, and partial eta squared values are listed for the interaction of group diagnosis and time course.

The Simplex Autism cohort was then split into two groups, those subjects that had been on one or more specific class of medications and those subjects not taking these medications. Each group has 8 subjects. The medications include stimulants, anti-psychotics, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). The 19 main effect ROIs were entered into group (medicated/not) by time course repeated measures ANOVAs, and no significant effects were observed (all P values > 0.1).

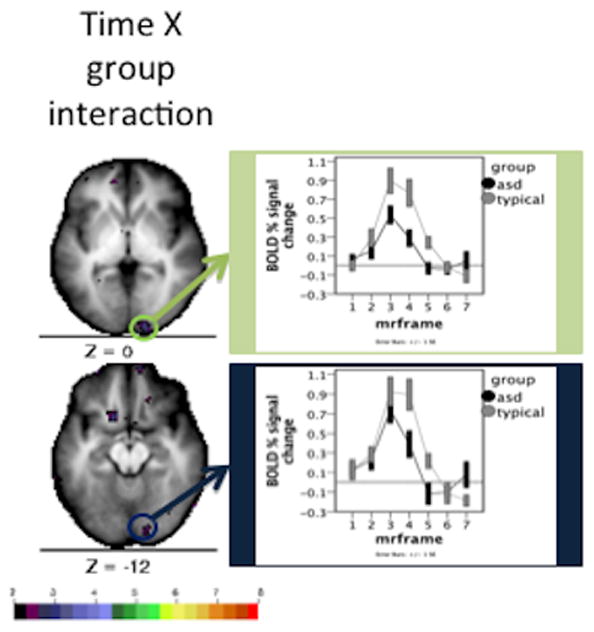

3.2. Examination of group by time interactions found in the primary analysis at a liberal threshold

For further assessment, the time course X diagnosis interaction map was examined at an extremely liberal, uncorrected threshold of Z > 1.9. Two ROIs in visual cortex were chosen from the statistical Z map for this liberal time course X group interaction image (Figure 6). Time courses were extracted from these ROIs and analyzed for group by time interactions using a time course by group repeated measures ANOVA (Table 4). One ROI shows a significant group by time interaction (Figure 6, top); the other region shows a group by time interaction trend (Figure 6, bottom).

Figure 6.

Time courses and statistical Z map for time course X group interaction using a quality control low Z value threshold. The map depicts the uncorrected Z values derived from the time course X group interaction. The mean time course for Simplex Autism (dark) and typical (light) cohorts are depicted for each of the chosen ROIs. Error bars represent 1 standard error of the mean. Color bar ranges from black (Z = 2) to red (Z = 8).

TABLE 4.

QC Analyses: Interactions at uncorrected significance

| Region | X | Y | Z | Df | F | P | Partial eta^2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| right visual | 15 | −97 | 0 | 3.19,95.73 | 4.3 | 0.006 | 0.13 |

| right visual | 15 | −91 | −11 | 2.36,70.68 | 2.8 | 0.06 | 0.085 |

The results from the ROI time course by group repeated measures ANOVA using the quality control low Z value threshold. These ROIs were extracted by using a peak-finding algorithm (described in the methods section), where all voxels had a Z > 1.9. Given X, Y, and Z coordinates correspond to the Talairach standard space. Degrees of freedom, F, and P, observed power, and partial eta squared values are depicted for the interaction of group diagnosis and time course.

3.3. Secondary analyses: All four runs combined per subject, and each run per subject

To help ensure that the lack of observed differences were not due to the selection of specific runs, all four runs acquired per subject were concatenated and analyzed using a diagnosis by time (2×7) repeated measures voxelwise ANOVA. After correcting for multiple comparisons, the voxelwise ANOVA revealed significant main effects of time course (Figure 7, top), and a small group by time course interaction (Figure 7, bottom). The region showing a significant interaction overlaps with the region showing an uncorrected interaction in the motion-controlled analysis.

Figure 7.

Statistical maps for the analysis of all four runs per subject. The Monte Carlo corrected statistical Z-score maps were derived from the main effect of time course (top) and group by time course interaction (bottom). Color bar ranges from black (Z = 2) to red (z = 8).

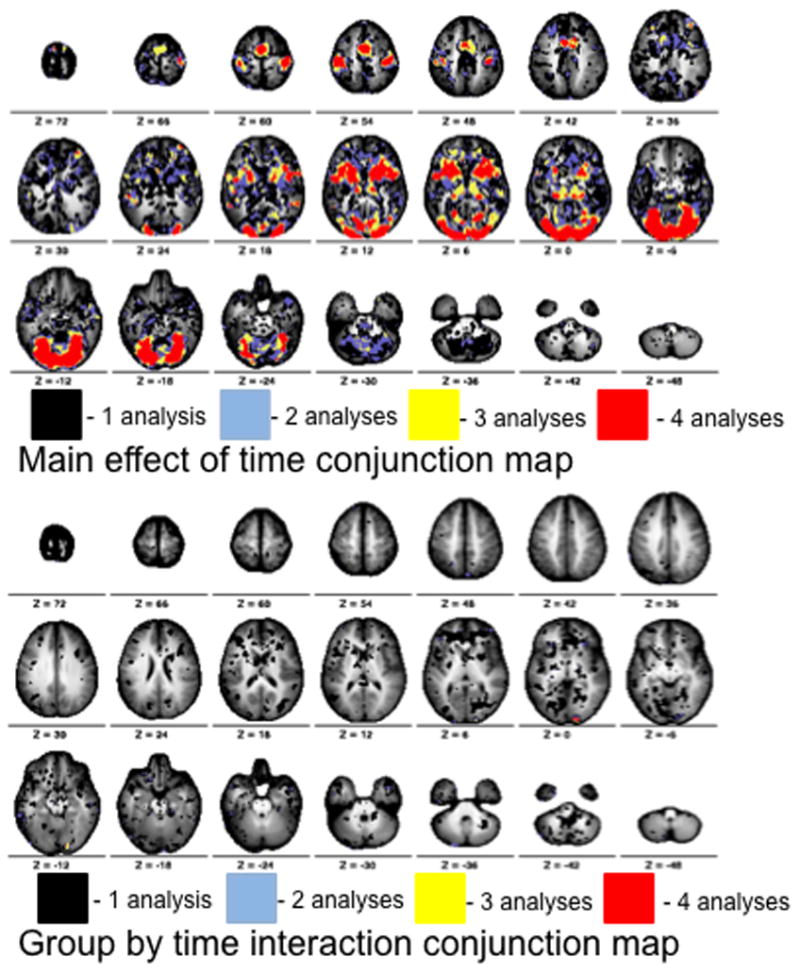

We also ran a group by time course (2×7) repeated measures ANOVA for each of the four runs the subjects performed. Because a single run contains fewer trials, the estimates derived from each subject’s GLM are weaker, and the ability to detect significant differences is limited. Therefore, the main effect and interaction images from each run were binarized at a threshold of Z > 1.9 and summed into a conjunction image. As shown in the main effect conjunction image, all 19 regions of interest show consistent significant activation for each of the four runs (Figure 8, top). However, the group by time interaction conjunction image shows a consistent activation for a region in right visual cortex, which is the same region identified in the other secondary analyses (Figure 8, bottom).

Figure 8.

Conjunction maps for the four analyses of each run per subject. The main effect of time and group by time interaction Z-score maps produced from each run were thresholded at a very liberal Z value (Z > 1.9) and summed. Summing the binarized maps produced a single conjunction map for the main effect of time (top) and interaction (bottom). Values on the map represent the number of analyses (1–4) which showed significant effects at a Z > 1.9. Color bar ranges from black (one analysis) to red (four analyses).

Regardless of whether two motion-matched runs, all four runs, or a conjunction of each individual run is analyzed, the only observed difference between Simplex Autism and typical cohorts is located in a very small portion of right visual cortex. Other regions from multiple vascular distributions show no differences in the hemodynamic response between Simplex Autism and typical cohorts.

4. Discussion

Through this study of BOLD time courses, we found that the hemodynamic response appears comparable between Simplex Autism and typical cohorts. Head motion can potentially induce artifacts in fMRI data, which can create false positive and false negative observations. When head motion was best matched between the two groups, no significant group effects were found. When groups were IQ and motion matched, no significant group by time interactions in the BOLD response were observed.

Comparisons of medicated to non-medicated Simplex Autism subjects revealed no significant differences in BOLD activity. It should be noted that this observation is limited due to very small numbers in each cell. It is also possible that different medications could have differing or opposing effects on the hemodynamic response. Nevertheless, the data acquired show no evidence that the combined effect of medications commonly used in people with ASD impacts the hemodynamic response in this sample.

The present study represents a first step in testing whether the hemodynamic response in autism is distinguishable from typically developing children. By using a task sufficiently simple that we can assume that the two groups are performing the task similarly (Church, et al. in press; Harris, et al. 2011), demonstrable differences in BOLD response could be interpreted as evidence for an altered hemodynamic response in autism. As stated above, our approach yielded no compelling evidence for Simplex Autism versus control differences in the shape of the task-evoked BOLD signal, in multiple comparisons-corrected analyses of motion-matched BOLD runs. There are several limitations, discussed immediately below.

When head motion was ignored or statistical thresholding was relaxed far below what we would consider appropriate in reporting an “fMRI effect”, a small region located in right visual cortex appears to be significantly different between Simplex Autism and typical cohorts. One could argue that this difference may represent an altered hemodynamic response localized exclusively to a small portion of right visual cortex. However, it is possible that the difference observed in right visual cortex may relate to an unmeasured behavior. Visual fixation was only qualitatively assessed, and because people with autism may have trouble with oculomotor control (Goldberg, et al. 2000; Goldberg, et al. 2002; Luna, et al. 2007; Minshew, et al. 1999) and fixating a point (Mahone, et al. 2006; Pruett, et al. 2011), it is possible that small differences in visual fixation may have led to some small differences in visual cortical activity. Because lurking variables can potentially confound the interpretation of fMRI data, it is important to be cautious in estimating the statistical significance of an effect, in interpreting a single finding, and in rigorously examining the quality of the data (Church, et al. in press).

The data presented here only directly pertain to neural processing resources that are engaged in this particular task. Combined electrophysiological and fMRI recordings from mice have shown that different neurons, even within the same brain region (Enager, et al. 2009), differ in their neurovascular coupling (Devonshire, et al. 2012; Sloan, et al. 2010). Therefore, it is possible that driving other populations of neurons might show differentials in fMRI responses.

Our claim, that the hemodynamic response is not altered in autism, is an operational claim, for our data do not measure neural activity directly. One interpretation of this operational claim is that the neurovascular coupling is comparable between autistic and typical cohorts. However, it is theoretically possible that some combination of altered neural activity and altered neurovascular coupling could negate each other, leaving no observed differences in BOLD activity in multiple vascular distributions. Combining MEG and/or EEG with fMRI acquisition might directly address this possibility, by providing convergent electrophysiological data that can dissociate effects of neural activity from effects of neurovascular coupling.

Because these limitations assume that both neural activity and neurovascular coupling are altered in autism, these limitations would seem to be more troubling if robust BOLD response differences were observed between the two groups. However, the data presented here show scant evidence of any meaningful difference in the hemodynamic response in ASD at these sample sizes for neural populations that are responsive to this task. A lack of significant group by time course interactions does not indicate that the hemodynamic response is completely “normal” in Simplex Autism. However, it is encouraging to see that the hemodynamic response appears comparable in multiple vascular distributions during a simple straightforward task. This finding is important for autism fMRI/fcMRI research because it indicates that, for studies of a similar sample size, when strong autism versus control differences are seen with BOLD contrast in the regions investigated in this study, the observation is more likely not attributable to differential neurovascular coupling, but reflects differences in underlying neural activity.

Many fMRI/fcMRI studies report differences between autistic and typical children

Differences may relate to differential neurovascular coupling

We compare visuomotor task-evoked BOLD signal in simplex autism to typical children

Hemodynamic response in simplex autism children is comparable to typical children

Results in autism studies likely reflect differences in neural activity not coupling

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative (“Brain Circuitry in Simplex Autism,” Steve Petersen – PI). John Pruett’s effort was supported by K12 EY16336. We thank Sarah Hoertel, for coordinating recruitment, scheduling, and assessments of the subjects. We also thank Kelly McVey for help with recruitment, scheduling, assessing, and scanning subjects. We thank Jen Simmons, Anna Abbacchi, Teddi Gray and others from the Constantino lab for assessing and/or recruiting subjects. We would also like to thank Dan Marcus and his lab for database support.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures

Eric Feczko reports no biomedical financial interest or potential conflicts of interest. Fran Miezin reports no biomedical financial interest or potential conflicts of interest. Dr. Schlaggar reports no biomedical financial interest or potential conflicts of interest. Dr. Constantino receives royalties on the Social Responsiveness Scale, which is published and distributed by Western Psychological Services. Dr. Petersen reports no biomedical financial interest or potential conflicts of interest. Dr. Pruett reports no biomedical financial interest or potential conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Cherkassky VL, Kana RK, Keller TA, Just MA. Functional connectivity in a baseline resting-state network in autism. Neuroreport. 2006;17(16):1687–90. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000239956.45448.4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church JA, Petersen SE, Schlaggar BL. Comment on “The physiology of developmental changes in BOLD functional imaging signals” by Harris, Reynell, and Attwell. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2011.10.003. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JD, MacWhinney B, Flatt M, Provost J. PsyScope: A new graphic interactive environment for designing psychology experiments. Behavioral Research Methods, Instruments, and Computers. 1993;25(2):257–271. [Google Scholar]

- Devonshire IM, Papadakis NG, Port M, Berwick J, Kennerley AJ, Mayhew JE, Overton PG. Neurovascular coupling is brain region-dependent. Neuroimage. 2012;59(3):1997–2006. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enager P, Piilgaard H, Offenhauser N, Kocharyan A, Fernandes P, Hamel E, Lauritzen M. Pathway-specific variations in neurovascular and neurometabolic coupling in rat primary somatosensory cortex. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2009;29(5):976–86. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg MC, Landa R, Lasker A, Cooper L, Zee DS. Evidence of normal cerebellar control of the vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR) in children with high-functioning autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2000;30(6):519–24. doi: 10.1023/a:1005631225367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg MC, Lasker AG, Zee DS, Garth E, Tien A, Landa RJ. Deficits in the initiation of eye movements in the absence of a visual target in adolescents with high functioning autism. Neuropsychologia. 2002;40(12):2039–49. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(02)00059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomot M, Belmonte MK, Bullmore ET, Bernard FA, Baron-Cohen S. Brain hyper-reactivity to auditory novel targets in children with high-functioning autism. Brain. 2008;131(Pt 9):2479–88. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris JJ, Reynell C, Attwell D. The physiology of developmental changes in BOLD functional imaging signals. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2011;1(3):199–216. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser MD, Hudac CM, Shultz S, Lee SM, Cheung C, Berken AM, Deen B, Pitskel NB, Sugrue DR, Voos AC, et al. Neural signatures of autism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(49):21223–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010412107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang HC, Burgund ED, Lugar HM, Petersen SE, Schlaggar BL. DUPLICATE-Comparison of functional activation foci in children and adults using a common stereotactic space. Neuroimage. 2003;19(1):16–28. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00038-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy DP, Courchesne E. The intrinsic functional organization of the brain is altered in autism. Neuroimage. 2008;39(4):1877–85. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.10.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logothetis NK, Pauls J, Augath M, Trinath T, Oeltermann A. Neurophysiological investigation of the basis of the fMRI signal. Nature. 2001;412:150–7. doi: 10.1038/35084005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Risi S, Lambrecht L, Cook EH, Jr, Leventhal BL, DiLavore PC, Pickles A, Rutter M. The autism diagnostic observation schedule-generic: a standard measure of social and communication deficits associated with the spectrum of autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2000;30(3):205–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Rutter M, Le Couteur A. Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised: a revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 1994;24(5):659–85. doi: 10.1007/BF02172145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luna B, Doll SK, Hegedus SJ, Minshew NJ, Sweeney JA. Maturation of executive function in autism. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61(4):474–81. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahone EM, Powell SK, Loftis CW, Goldberg MC, Denckla MB, Mostofsky SH. Motor persistence and inhibition in autism and ADHD. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2006;12(5):622–31. doi: 10.1017/S1355617706060814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAvoy MP, Ollinger JM, Buckner RL. Cluster size thresholds for assessment of significant activation in fMRI. NeuroImage. 2001;13(6-2):S198. [Google Scholar]

- Miezin FM, Maccotta L, Ollinger JM, Petersen SE, Buckner RL. Characterizing the hemodynamic response: Effects of presentation rate, sampling procedure, and the possibility of ordering brain activity based on relative timing. NeuroImage. 2000;11:735–759. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2000.0568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minshew NJ, Luna B, Sweeney JA. Oculomotor evidence for neocortical systems but not cerebellar dysfunction in autism. Neurology. 1999;52(5):917–22. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.5.917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monk CS, Peltier SJ, Wiggins JL, Weng SJ, Carrasco M, Risi S, Lord C. Abnormalities of intrinsic functional connectivity in autism spectrum disorders. Neuroimage. 2009;47(2):764–72. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.04.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mostofsky SH, Powell SK, Simmonds DJ, Goldberg MC, Caffo B, Pekar JJ. Decreased connectivity and cerebellar activity in autism during motor task performance. Brain. 2009;132(Pt 9):2413–25. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller RA, Kleinhans N, Kemmotsu N, Pierce K, Courchesne E. Abnormal variability and distribution of functional maps in autism: an FMRI study of visuomotor learning. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(10):1847–62. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.10.1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noonan SK, Haist F, Muller RA. Aberrant functional connectivity in autism: evidence from low-frequency BOLD signal fluctuations. Brain Res. 2009;1262:48–63. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.12.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ollinger JM, Corbetta M, Shulman GL. Separating processes within a trial in event-related functional MRI II. Analysis. Neuroimage. 2001a;13(1):218–229. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2000.0711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ollinger JM, Shulman GL, Corbetta M. Separating processes within a trial in event-related functional MRI I. The method. Neuroimage. 2001b;13(1):210–217. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2000.0710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruett JR, Jr, Lamacchia A, Hoertel S, Squire E, McVey K, Todd RD, Constantino JN, Petersen SE. Social and non-social cueing of visuospatial attention in autism and typical development. J Autism Dev Disord. 2011;41(6):715–731. doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-1090-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan HL, Austin VC, Blamire AM, Schnupp JW, Lowe AS, Allers KA, Matthews PM, Sibson NR. Regional differences in neurovascular coupling in rat brain as determined by fMRI and electrophysiology. Neuroimage. 2010;53(2):399–411. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder AZ. Difference image vs. ratio image error function forms in PET-PET realignment. In: Myer R, Cunningham VJ, Bailey DL, Jones T, editors. Quantification of Brain Function Using PET. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1996. pp. 131–137. [Google Scholar]

- Weng SJ, Wiggins JL, Peltier SJ, Carrasco M, Risi S, Lord C, Monk CS. Alterations of resting state functional connectivity in the default network in adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Brain Res. 2010;1313:202–14. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.11.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]