Abstract

Background

The first methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) clinic in Tanzania was launched in February 2011 to address an emerging HIV epidemic among people who inject drugs (PWID). We conducted a retrospective cohort study to understand factors associated with linkage to HIV care and explore how a MMT clinic can serve as a platform for integrated HIV care and treatment.

Methods

This study utilized routine programmatic and clinical data on clients enrolled in methadone at Muhimbili National Hospital from February 2011 to January 2013. Multivariable proportional hazards regression model were used to examine time to initial CD4 count.

Results

Final analyses included 148 HIV-positive clients, contributing 31.7 person-years. At 30, 60 and 90 days, the probability of CD4 screening was 40% (95% CI: 32–48%), 55% (95% CI: 47%–63%) and 63% (95% CI: 55%–71%), respectively. Clients receiving high methadone doses (≥85mg/day) [aHR:1.68, 95% CI:(1.03, 2.74)] had higher likelihood of CD4 screening than those receiving low doses (<85 mg/day). Clients with primary education or lower [aHR:1.62, 95% CI:(1.05, 2.51)] and self-reported poor health [aHR:1.96, 95% CI:(1.09, 3.51)] were also more likely to obtain CD4 counts. Clients with criminal arrest history [aHR: 0.56, 95% CI: (0.37, 0.85)] were less likely to be linked to care. Among 17 ART-eligible clients (CD4≤200), 12 (71%) initiated treatment, of which 7 (41%) initiated within 90 days.

Conclusions

Levels of CD4 screening and ART initiation were similar to Sub-Saharan programs caring primarily for non-PWID. Adequate methadone dosing is important in retaining clients to maximize HIV treatment benefits and allow for successful linkage to services.

Introduction

Drug trafficking through East Africa emerged in the mid-1980s and continues to increase.1 Seizures of heroin in Africa, especially in East Africa, have increased ten-fold since 2009.1 As of 2011, an estimated 533,000 opiate consumers live in East Africa with an estimated 50,000 people who inject drugs (PWID) in Tanzania.2 In Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, PWID have an estimated HIV prevalence of 42%–51%, compared to 6.9% among the general population in the city.3,4 Furthermore, high HIV prevalence is accompanied by high burdens of hepatitis C (57%–76%) and active pulmonary tuberculosis (4%).5–7

Methadone maintenance treatment (MMT), HIV testing and counseling (HTC) and antiretroviral therapy (ART), are considered essential components of the comprehensive package of HIV prevention interventions for PWID, endorsed by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), World Health Organization (WHO), United Nations Office on Drug and Crime (UNODC) and Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS).8 Methadone is an effective treatment for opioid dependence, associated with lowering morbidity and mortality and reducing sexual and injection-related risk behaviors associated with drug use9–14 Retention in MMT has led to optimized HIV prevention and treatment benefits, including routine testing and counseling and linkage to care and treatment for individuals living with HIV.9,15–17 As such, methadone is designated as an Essential Medicine by the WHO.18

Studies from Sub-Saharan Africa estimate 59%–72% of individuals diagnosed with HIV ever obtain CD4 screening.19,20 In 2012, 59% of ART-eligible individuals in Tanzania, based on outdated CD4 criteria (<200), were currently on treatment.21 Despite scale-up of ART for people living with HIV, up to 26% of care and treatment clients become lost-to-follow-up. 21 Compared to the general population, PWID face additional barriers, including delays in and denial of the provision of healthcare services, harassment by law enforcement and fear of criminalization and stigmatization that impact access to and uptake of medical services in traditional settings.22–26 Because methadone clinics are designed to address the clinical needs of PWID, they can offer a unique venue for the provision of a full range of HIV-related and other health services.

We conducted a retrospective cohort study to understand the factors associated with linkage to HIV care and explore how a MMT clinic can serve as a platform for integrated HIV care and treatment. We hypothesize that enrollment in MMT with higher dosing is associated with timely linkage to HIV care.

Methods

Study Setting

The first publicly-funded MMT clinic in Tanzania was launched in February 2011, offering daily directly observed methadone at Muhimbili National Hospital (MNH) in Dar es Salaam. As part of routine care, clients were offered voluntary HIV testing and counseling upon enrollment and at routine follow-up periods. For clients who tested HIV-positive, the clinic performed blood draws and transported samples for CD4 screening to the central laboratory at MNH. Using traditional methods, the central laboratory conducted CD4 count testing and reported results back to the methadone clinic. MMT and clinical HIV services were available at MNH but not co-located. Therefore, clients were provided escorted, in-person referrals to HIV clinical services at the care and treatment center (CTC), situated in a separate building on the hospital campus. For eligible individuals, the methadone clinic facilitated access to HIV therapy and provided daily co-dispensing of methadone and ART. Clients may also receive HIV screening through program caravans, which work in parallel with the methadone program to reach key populations in the surrounding district. Caravans provide mobile counseling and testing and referrals to HIV care and treatment centers but do not provide methadone dosing or direct HIV care.

Study Population

Study subjects included MMT clients enrolled from February 2011 to January 2013 who tested positive for HIV following enrollment in methadone. Inclusion criteria for methadone initiation have been described previously.27 Additional criteria included: 1) positive HIV test within seven days before or any time after MMT initiation; 2) laboratory or clinical notes confirming HIV result; and 3) actively receiving MMT as of HIV-positive test date. We sought to capture individuals who tested positive for HIV through MMT-based services and were not previously been linked to care. Therefore, individuals who indicated an approximate date of first HIV-positivity prior to enrollment or received HIV care elsewhere were excluded from analysis.

Data Sources

This study utilized de-identified routine clinical and program monitoring data from the MMT clinic, which were extracted from the electronic databases. As part of routine care, health care providers and social workers conducted an in-person baseline assessment to collect demographic, health history, addiction severity,28 mental health,29 and HIV risk behavior data. Linkage to care data, including HIV testing and CD4 result dates were obtained through medical chart review and abstraction. Daily methadone dosing data for each client were collected by the pharmacy.

Measures

Exposures

Our primary exposure of interest was methadone dose. The mean daily methadone dose during the first three months of treatment was calculated and categorized into low (<85 mg/day) or high (≥85 mg/day). Categorization of dose was based on prior research with this cohort and other literature with regards to methadone dosing.30–33 Additional exposures of interest included demographics, sexual and injection-related risk factors; mental health; history of physical or sexual abuse; and arrest history.

Outcomes

Linkage to care for individuals testing HIV-positive was defined as obtaining a CD4 count. The number of days between first HIV-positive test and CD4 results was the primary outcome of interest. Follow-up time began at the HIV-positive result date (t0) and ended with the date of CD4 result, the last methadone dose for those experiencing a censoring event (death, involuntary discharge, medical withdrawal, or defaulting (i.e. missed 21 consecutive doses)) or January 31, 2013, whichever occurred first. If a client tested positive through program caravans within one week of MMT enrollment, the initiation date was used as t0.

Statistical Methods

Multivariable cox proportional hazards regression models were used to assess the relationship of exposures with obtaining a CD4 count among clients living with HIV. Backward stepwise regression with a criterion p-value of 0.2 was used to select the variables for the multivariable model. Forward stepwise regression was used in sensitivity analysis to confirm variables. Cumulative incidence of CD4 testing, taking into account the competing risk of censoring events, was plotted by methadone dose. Hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated to compare outcomes between groups. The proportional hazards assumption was tested using the Schoenfeld residuals. Self-reported poor health was found to have time-varying effects with linkage to care and was therefore specified in the model to estimate associations in early follow-up (≤30 days) and later follow-up (>30 days). Statistical analyses were conducted using Stata 12.1 (College Station, TX).

Ethics Statement

The use and analysis of de-identified, programmatic data was approved by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, E&I Review Services in the United States as well as the ethical review committees at Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences and the National Institute of Medical Research in Tanzania as program evaluation and non-human subjects research.

Results

MMT Clients

During the study period, 629 individuals initiated MMT. Average age at enrollment was 32 (SD±6) years and 93% of clients were male. Among 469 (75%) clients who tested for HIV, 185 (39%) were confirmed HIV-positive. Excluded cases included 21 (11%) that were missing test dates and 16 (9%) that tested positive outside the inclusion window. The final analysis included 148 HIV-positive MMT clients, contributing 31.7 person-years of follow-up. Table 1 includes baseline characteristics of methadone clients living with HIV, disaggregated by methadone dose.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Methadone Clients Living with HIV in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania (N=148)

| Methadone Dose

|

||

|---|---|---|

| Low (<85 mg/day) n=110 |

High (≥85 mg/day) n=38 |

|

| Demographics | ||

| Female, | 16 | 16 |

| > 30 years of age | 72 | 79 |

| Less than primary education | 66 | 76 |

| Has at least one child | 33 | 32 |

| Married | 8 | 16 |

| Sexual Risk Factors | ||

| Multiple Sex Partners in last 6 months | 22 | 8 |

| Risky Sex in last 6 months1 | 49 | 46 |

| Injection Risk Factors | ||

| Years of Heroin Use | ||

| 0 to 10 | 50 | 65 |

| 11 to 20 | 42 | 29 |

| Over 20 | 8 | 6 |

| Flash-blood2 | 13 | 5 |

| Share Needles at Last Injection | 17 | 16 |

| Share other Equipment at Last Injection | 18 | 16 |

| Polysubstance Use (heroin with alcohol, cocaine, or benzodiazepine) | 25 | 32 |

| Mental Health | ||

| Depression in Last 30 Days3 | 22 | 21 |

| Anxiety in Last 30 Days3 | 20 | 15 |

| History of Abuse | ||

| Any History of Physical Abuse | 11 | 9 |

| Any History of Sexual Abuse | 2 | 6 |

| Other Factors | ||

| Self-reported “poor” health4 | 57 | 59 |

| Ever been arrested | 53 | 41 |

| Received HIV test within one month of MAT initiation | 55 | 84 |

| HIV first test upon re-initiating (after defaulting) | 5 | 5 |

Data are presented as percentages by methadone dose category

Vaginal or anal intercourse with no or inconsistent condom use

Injecting blood from another drug user who has recently injected heroin

Self-reported exposures

General health indicator from SF-12

Linkage to Care

At the end of the study, 119 (80%) clients received at least one CD4 count and were active methadone clients, 14 (9%) were active clients but had not received screening, 14 (9%) defaulted from MMT prior to screening, and one (1%) was deceased. At 30, 60 and 90 days, the probability of clients undergoing CD4 screening was 40% (95% CI: 32–48%), 55% (95% CI: 47%–63%), and 63% (95% CI: 55%–71%), respectively.

Factors Associated with Linkage to Care

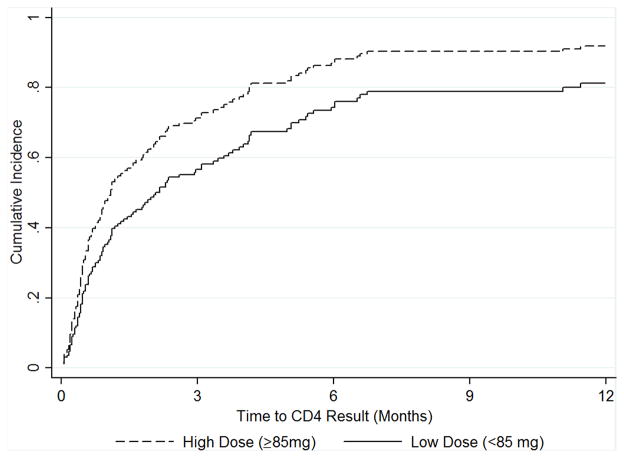

Figure 1 illustrates the cumulative incidence of CD4 screening by methadone dose. Table 2 includes adjusted and unadjusted HRs for the associations of patient characteristics and linkage to CD4 count among clients living with HIV. In the multivariable model, clients receiving ≥85 mg methadone/day [aHR: 1.68, 95% CI: (1.03, 2.74)] had higher likelihood of CD4 screening than those receiving <85 mg methadone/day. In addition, clients with primary education or lower [aHR: 1.62, 95% CI: (1.05, 2.51)] and self-reported poor health [aHR (≤30 days): 1.96, 95% CI: (1.09, 3.51)] were more likely to obtain CD4 counts. Self-reported poor health was found to have time-varying effects that attenuated after the first 30 days of methadone treatment [aHR (>30 days): 1.26, 95% CI: (0.72, 2.20)]. Compared to clients with no arrest history, clients with a history of arrest [aHR: 0.56, 95% CI: (0.37, 0.85)] were less likely to obtain a CD4 count. Results from the sensitivity analysis showed qualitatively similar results.

Figure 1.

Cumulative Incidence of Initial CD4 Screening by Methadone Dose

Table 2.

Unadjusted and Adjusted Hazard Ratios for Linkage to CD4 Count among Methadone Clients Living with HIV in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania (N=148)

| Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | p-value | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Female | 1.27 (0.78, 2.06) | 0.339 | 1.15 (0.69, 1.91) | 0.600 |

| > 30 years of age | 0.76 (0.46, 1.25) | 0.281 | ||

| Less than primary education | 1.54 (1.02, 2.32) | 0.039 | 1.62 (1.05, 2.51) | 0.024 |

| Has at least one child | 0.87 (0.59, 1.29) | 0.483 | ||

| Married | 0.99 (0.53, 1.84) | 0.965 | ||

| Sexual Risk Factors | ||||

| Multiple Sex Partners in last 6 months | 0.66 (0.40, 1.09) | 0.102 | ||

| Risky Sex in last 6 months1 | 1.28 (0.88, 1.86) | 0.195 | ||

| Injection Risk Factors | ||||

| Years of Heroin Use | ||||

| 0 to 10 | ref. | |||

| 11 to 20 | 0.86 (0.58, 1.28) | 0.13 | ||

| Over 20 | 0.56 (0.27, 1.19) | |||

| Flash-blood2 | 0.98 (0.56, 1.70) | 0.937 | ||

| Share Needles at Last Injection | 1.32 (0.81, 2.15) | 0.258 | 1.43 (0.85, 2.42) | 0.181 |

| Share other Equipment at Last Injection | 1.20 (0.74, 1.94) | 0.461 | ||

| Polysubstance Use (heroin with alcohol, cocaine, or benzodiazepine) | 0.95 (0.63, 1.43) | 0.794 | ||

| Mental Health | ||||

| Depression in Last 30 Days | 0.87 (0.54, 1.40) | 0.576 | ||

| Anxiety in Last 30 Days | 0.83 (0.50, 1.36) | 0.455 | ||

| History of Abuse | ||||

| Any History of Physical Abuse | 1.08 (0.58, 2.03) | 0.803 | ||

| Any History of Sexual Abuse | 2.16 (0.68, 6.86) | 0.191 | 2.37 (0.68, 8.28) | 0.175 |

| Other Factors | ||||

| High initial methadone dose (≥85mg) | 1.72 (1.10, 2.67) | 0.017 | 1.68 (1.03, 2.74) | 0.036 |

| Self-reported “poor” health | 1.24 (0.85, 1.79) | 0.26 | 1.96 (1.09, 3.51)† | 0.024 |

| Ever been arrested | 0.67 (0.46, 0.98) | 0.037 | 0.56 (0.37, 0.85) | 0.007 |

| Received HIV test within one month of MAT initiation | 1.39 (0.95, 2.0) | 0.088 | ||

| HIV first test upon re-initiation (after defaulting) | 0.61 (0.23, 1.67) | 0.34 | ||

Time-varying effects found. Effects were attenuated after 30 days of methadone (aHR >30 days: 1.26 (0.72, 2.20), p-value 0.423)

Vaginal or anal intercourse with no or inconsistent condom use

Injecting blood from another drug user who has recently injected heroin

Self-reported exposures

General health indicator from SF-12

ART Eligibility and Initiation

Median initial CD4 count was 458 cells/μL (IQR: 296,673) and 17 clients had CD4≤200, which served as the criterion for ART eligibility during our study period. Among ART-eligible clients, 12 (71%) initiated treatment, of which 7 (41%) initiated within 90 days of their CD4 result.

Discussion

This first report on linkage to HIV care among methadone clients in Tanzania indicates similar levels of CD4 screening and ART initiation when compared to estimates from programs caring for non-PWID throughout Sub-Saharan Africa.19,20 We view this as a positive outcome because PWID, in general, tend to be at higher risk of being lost to follow-up than the general population living with HIV.34

This study expands on our previous implementation science research, focused on identifying gaps and developing strategies for improved HIV service delivery for drug users in Tanzania.27,30,35 Previous research indicated the proportion of MNH clients retained in methadone at 12 months was 57% and that clients receiving higher methadone doses had a lower risk of attrition.30,36–38 Engagement and retention in MMT is critical because 82% of PWID who drop out return to injection within 10 to 12 months.14 In addition, the stability provided to clients through methadone treatment is essential for successful linkage to other health services. These results support a growing body of literature that engagement in MMT can lead to optimized HIV prevention and treatment benefits.9,13,15–17 Our data indicated that stabilization through higher methadone doses increased the probability of obtaining a CD4 count. Our results also showed stronger effects of self-perceived poor health, a component of health-related quality of life, on linkage in the first 30 days of methadone treatment. In contrast, individuals with a history of arrest were less likely to be linked to care, highlighting the need for enhanced case management. Successful implementation approaches should incorporate appropriate, adequate dosing strategies and concurrently address individual-level factors to keep clients engaged in care.

Enhancing HIV prevention, care and treatment services for PWID and other key populations is critical to the global response to HIV. Innovative, evidence-based strategies that have shown effectiveness in traditional settings should be adapted and operationalized in settings that serve hard-to-reach populations. In particular, it is important to consider client-centered, integrated strategies that link and retain clients into needed services.35,39

Although 80% of clients were linked to care during the study period, reductions in the amount of time to linkage are needed. In some cases, CD4 testing took several months. The methadone program, which currently requires daily attendance, can provide a platform for regular HIV testing and immediate linkage to care for those who test positive. However, current CD4 testing technology burdens systems and clients as specimens are drawn at the clinic and transported to the central hospital laboratory. Reagent shortages may require transport of samples to an off-site laboratory, further delaying the CD4 testing process. The use of point–of-care (POC) technologies in HIV clinics has improved clinical monitoring and streamlined ART delivery in other settings.40–43 In addition, field studies demonstrate feasibility and technical validity in program settings in Africa.41–43 Integration of point-of-care CD4 instruments in the methadone clinic could allow clients to receive both HIV and CD4 test results in a single visit, thus potentially closing the loss-to-care gap.

As a critical next step in the continuum of care, improvements in linkage to HIV treatment are needed. During the study period, the clinic provided escorted referrals to the off-site CTC and worked to facilitate access to ART. However, many factors, some of which can be complicated by drug use, contribute to timely ART initiation. While not the focus of this paper, examination of systemic, structural and individual level barriers to ART initiation will be important to fully characterize the HIV treatment cascade among our client population and inform the development of new approaches.

Strengths of the study included standardized clinical protocols, client tracing and data recording. However, clinical HIV data relied on accurate chart abstraction and timely transfer of information from the central hospital laboratory and CTC, located outside of the methadone clinic. The primary limitation is the observational nature of our research. As a result, the potential for unmeasured or mis-measured factors to bias our results existed. Clients who defaulted from methadone were not systematically followed-up to assess CD4 screening in other locations. In this study, we assumed that these individuals did not receive HIV-related services elsewhere, given the levels of stigma and refusal of services that PWID commonly face. Future analyses will examine how attrition from and re-entry into the methadone program affect continuity of HIV testing and linkage to care. Additionally, the nature of our data limited our capacity to evaluate the sub-processes of the care continuum, including time between blood draw, laboratory testing and CD4 count result. We were unable to evaluate the proportion of clients receiving CD4 results. However we assume that given the structure of care, a high proportion of clients return for their CD4 results during a follow-up visit. As the program expands to integrate additional HIV services, a strengthened monitoring and evaluation system will be critical to documenting and improving the care pathway.

In conclusion, our research supports the use of methadone programs as a gateway to HIV prevention, treatment and care for PWID and as platforms for integrated health services in resource-constrained settings. As programs expand in Tanzania and initiate in other African countries, identifying and implementing strategies that engage clients are critical to further linking PWID into needed health services. Our results highlight the importance of higher doses of methadone to maximize HIV treatment benefits for PWID. Future initiatives will focus on developing an integrated platform of MMT and HIV treatment delivery to improve linkage to care and ART initiation.

Acknowledgments

Funding Source: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse [Grant number 1R34DA037787].

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: We declare no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Olivia C. Tran, Email: ochang@pgaf.org, Pangaea Global AIDS Foundation, 436 14th Street, Suite 920, Oakland, CA 94612, (510) 326-5098.

R. Douglas Bruce, Pangaea Global AIDS Foundation, Yale University, New Haven, CT.

Frank Masao, Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences, Muhimbili National Hospital, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

Omary Ubuguyu, Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences, Muhimbili National Hospital, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

Norman Sabuni, Ministry of Health and Social Welfare, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

Jessie Mbwambo, Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences, Muhimbili National Hospital, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

Barrot H. Lambdin, Pangaea Global AIDS Foundation, University of Washington, Department of Global Health.

Bibliography

- 1.UNODC. World Drug Report. Vienna, Austria: 2013. [Accessed 2 January 2014]. Available at: http://www.unodc.org/unodc/secured/wdr/wdr2013/World_Drug_Report_2013.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.UNODC. [Accessed 2 January 2014];The Global Afghan Opium Trade: A Threat Assessment. 2011 Available at: http://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/Studies/Global_Afghan_Opium_Trade_2011-web.pdf.

- 3.Williams ML, McCurdy SA, Bowen AM, et al. HIV seroprevalence in a sample of Tanzanian intravenous drug users. AIDS Educ Prev. 2009;21(5):474–483. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2009.21.5.474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tanzania Commission for AIDS, Zanzibar AIDS Commission, National Bureau of Statistics, Office of Chief Government Statistician Zanzibar, ICF International. [Accessed 10 December 2014];Third Tanzania HIV/AIDS and Malaria Indicator Survey 2011–2012. Available at http://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/AIS11/AIS11.pdf.

- 5.Nyandindi C, Mbwambo J, McCurdy S, Lambdin B, Copenhaver M, Bruce R. College on Problems of Drug Dependence. San Diego, CA: 2013. Prevalence of HIV, Hepatitis C and depression among people who inject drugs in the Kinondoni Municipality in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang O, Bruce RD, Masao F, et al. Risk factors associated with HCV infection and prevalence of HIV-HCV co-infection among people who inject drugs receiving medication-assisted treatment in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. International AIDS Conference; 2014; Melbourne, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gupta A, Mbwambo J, Mteza I, et al. Active case finding for tuberculosis among people who inject drugs on methadone treatment in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2014;18(7):793–798. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.13.0208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.PEPFAR. Comprehensive HIV Prevention for People Who Inject Drugs. [Accessed 4 January 2014];Revised Guidance. Available at: http://www.pepfar.gov/documents/organization/144970.pdf.

- 9.Bruce RD. Methadone as HIV prevention: high volume methadone sites to decrease HIV incidence rates in resource limited settings. Int J Drug Policy. 2010;21(2):122–124. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Metzger DS, Woody GE, McLellan AT, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus seroconversion among intravenous drug users in- and out-of-treatment: an 18-month prospective follow-up. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1993;6(9):1049–1056. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Connock M, Juarez-Garcia A, Jowett S, et al. Methadone and buprenorphine for the management of opioid dependence: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2007;11(9):1–171. iii–iv. doi: 10.3310/hta11090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gibson DR, Flynn NM, McCarthy JJ. Effectiveness of methadone treatment in reducing HIV risk behavior and HIV seroconversion among injecting drug users. AIDS. 1999;13(14):1807–1818. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199910010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Woody GE, Bruce D, Korthuis PT, et al. HIV risk reduction with buprenorphine-naloxone or methadone: findings from a randomized trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;66(3):288–293. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ball JC, Ross A. The effectiveness of methadone maintenance treatment: Patients, programs, services and outcome. xiv. New York, NY, US: Springer-Verlag Publishing; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uhlmann S, Milloy MJ, Kerr T, et al. Methadone maintenance therapy promotes initiation of antiretroviral therapy among injection drug users. Addiction. 2010;105(5):907–913. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02905.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wood E, Hogg RS, Kerr T, Palepu A, Zhang R, Montaner JS. Impact of accessing methadone on the time to initiating HIV treatment among antiretroviral-naive HIV-infected injection drug users. AIDS. 2005;19(8):837–839. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000168982.20456.eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knowlton A, Hoover DR, Chung S-e, Celentan DD, Vlahov D, Latkina CA. Access to medical care and service utilization among injection drug users with HIV/AIDS. 2001;64(1):55–62. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00228-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.WHO. [Accessed 8 December 2014];WHO Model List of Essential Medicines: 17th List. Available at: http://www.who.int/medicines/publications/essentialmedicines/en/

- 19.Rosen S, Matthew P. Retention in HIV Care between Testing and Treatment in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Review. PLOS Medicine. 2011;8(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mugglin C, Estill J, Wandeler G, et al. Loss to programme between HIV diagnosis and initiation of antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa: systematic review and meta-analysis. Trop Med Int Health. 2012;17(12):1509–1520. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2012.03089.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.PEPFAR. [Accessed on 10 December 2014];Tanzania Operational Plan Report: FY. 2013 Available at: http://www.pepfar.gov/documents/organization/222184.pdf.

- 22.Wolfe D, Carrieri MP, Shepard D. Treatment and care for injecting drug users with HIV infection: a review of barriers and ways forward. Lancet. 2010;376(9738):355–366. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60832-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mimiaga MJ, Safren SA, Dvoryak S, Reisner SL, Needle R, Woody G. “We fear the police, and the police fear us”: structural and individual barriers and facilitators to HIV medication adherence among injection drug users in Kiev, Ukraine. AIDS Care. 2010;22(11):1305–1313. doi: 10.1080/09540121003758515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wood E, Kerr T, Tyndall MW, Montaner JS. AIDS. Vol. 22. England: 2008. A review of barriers and facilitators of HIV treatment among injection drug users; pp. 1247–1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paxton S, Gonzales G, Uppakaew K, et al. AIDS-related discrimination in Asia. AIDS Care. 2005;17(4):413–424. doi: 10.1080/09540120412331299807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ding L, Landon BE, Wilson IB, Wong MD, Shapiro MF, Cleary PD. Predictors and consequences of negative physician attitudes toward HIV-infected injection drug users. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(6):618–623. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.6.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lambdin BH, Bruce RD, Chang O, et al. Identifying Programmatic Gaps: Inequities in Harm Reduction Service Utilization among Male and Female Drug Users in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. PLOS ONE. 2013;8(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, et al. The fifth edition of the Addiction Severity Index. Journal of substance abuse treatment. 1992;9(3):199–213. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(92)90062-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Rickels K, Uhlenhuth EH, Covi L. The Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL). A measure of primary symptom dimensions. Mod Probl Pharmacopsychiatry. 1974;7(0):79–110. doi: 10.1159/000395070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lambdin BH, Masao F, Chang O, et al. Methadone Treatment for HIV Prevention-Feasibility, Retention, and Predictors of Attrition in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Clin Infect Dis. 2014 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fareed A, Casarella J, Amar R, Vayalapalli S, Drexler K. Methadone maintenance dosing guideline for opioid dependence, a literature review. J Addict Dis. 2010;29(1):1–14. doi: 10.1080/10550880903436010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brady TM, Salvucci S, Sverdlov LS, et al. Methadone dosage and retention: an examination of the 60 mg/day threshold. J Addict Dis. 2005;24(3):23–47. doi: 10.1300/J069v24n03_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mattick RP, Kimber J, Breen C, Davoli M. Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(2):Cd002207. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002207.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mathers BM, Degenhardt L, Ali H, et al. HIV prevention, treatment, and care services for people who inject drugs: a systematic review of global, regional, and national coverage. Lancet. 2010;375(9719):1014–1028. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60232-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bruce RD, Lambdin B, Chang O, et al. Lessons from Tanzania on the integration of HIV and tuberculosis treatments into methadone assisted treatment. Int J Drug Policy. 2014;25(1):22–25. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2013.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sarasvita R, Tonkin A, Utomo B, Ali R. Predictive factors for treatment retention in methadone programs in Indonesia. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2012;42(3):239–246. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2011.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bao YP, Liu ZM, Epstein DH, Du C, Shi J, Lu L. A meta-analysis of retention in methadone maintenance by dose and dosing strategy. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2009;35(1):28–33. doi: 10.1080/00952990802342899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang PW, Wu HC, Yen CN, et al. Change in quality of life and its predictors in heroin users receiving methadone maintenance treatment in Taiwan: an 18-month follow-up study. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2012;38(3):213–219. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2011.649222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sylla L, Bruce RD, Kamarulzaman A, Altice FL. Integration and co-location of HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and drug treatment services. Int J Drug Policy. 2007;18(4):306–312. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wynberg E, Cooke G, Shroufi A, Reid SD, Ford N. Impact of point-of-care CD4 testing on linkage to HIV care: a systematic review. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2014:17. doi: 10.7448/IAS.17.1.18809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jani IV, Sitoe NE, Alfai ER, et al. Effect of point-of-care CD4 cell count tests on retention of patients and rates of antiretroviral therapy initiation in primary health clinics: an observational cohort study. Lancet. 2011;378(9802):1572–1579. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61052-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Larson BA, Schnippel K, Ndibongo B, et al. Rapid point-of-care CD4 testing at mobile HIV testing sites to increase linkage to care: an evaluation of a pilot program in South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;61(2):e13–17. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31825eec60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mtapuri-Zinyowera S, Chideme M, Mangwanya D, et al. Evaluation of the PIMA point-of-care CD4 analyzer in VCT clinics in Zimbabwe. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55(1):1–7. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181e93071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]