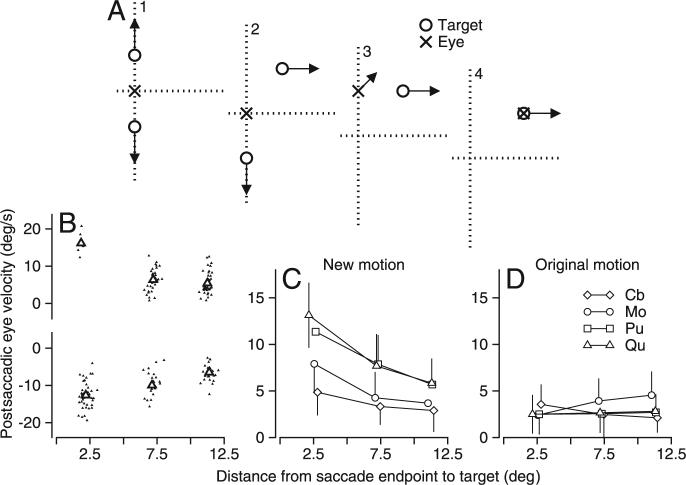

Figure 3.

Relationship between postsaccadic eye velocity and the distance from the endpoint of the saccade to the target position in the presence of a distracter. A, Schematic diagram showing the task as a sequence of four snapshots in time. A1, Two targets (open circles) began moving in opposite directions away from the fixation point and the eye (x). A2, One of the targets is displaced and begins to move orthogonally, where as the other continues along the original trajectory. A3, A saccade is made to the old location of one of the targets, and the eyes begin to move smoothly; the second target disappears. A4, A saccade was made to the new location of the target, followed by proper tracking. B, Plot of postsaccadic eye velocity in the direction of new motion as a function the distance between target and eye at the end of the saccade for one monkey. Dots show data for individual trials, and larger symbols show means for the three different amplitudes of displacement of target position. Positive and negative values of postsaccadic eye velocity were taken from trials in which the new target motion was rightward or leftward. C, Means and SDs of the absolute value of postsaccadic eye velocity in the direction of new motion for all monkeys used in each experiment. Different symbols correspond to different monkeys. D, The mean and SD of the absolute value of postsaccadic eye velocity in the direction of the original motion.