Abstract

Purpose

Despite advances in therapy for the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer, many patients succumb to their hepatic disease burden. Current immunotherapeutic strategies are likely limited by inhibitory signals from the tumor. To successfully eliminate tumor deposits within an organ, the appropriate immunologic milieu to amplify anti-tumor responses must be developed.

Methods

Here we use a murine model utilizing the CT26 colon cancer cell line to analyze primary and memory tumor-specific T-cell responses induced by an attenuated actin A and internalin B deleted immunodominant tumor-associated antigen expressing strain of Listeria monocytogenes for the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer.

Results

Treatment of mice bearing established hepatic metastases with this Listeria monocytogenes strain led to the generation of a strong initial tumor specific cytotoxic CD8+T-cell response which successfully treated ninety percent of animals. Tumor antigen-specific central and effector memory T-cells were also generated and protected against tumor re-challenge. These cell populations when measured before and after tumor re-challenge, showed a significant expansion of antigen-specific effector CD8+ effector memory T-cells. This strain of Listeria monocytogenes was able to down-modulate the expression of the immune checkpoint molecule, PD-1, within the tumor microenvironment but had variable effects on CTLA-4 expression.

Conclusions

This Listeria monocytogenes strain generated a highly effective anti-tumor T-cell response providing a basis for the development of this vaccine platform in patients with liver metastases.

Introduction

Cancer immunotherapy is successful when it eliminates tumor cells and prevents recurrence with the generation of an antigen-specific memory T-cell response. Previous strategies that focused on peptides or cytokine-secreting cancer vaccines, adoptive cytotoxic T-cell transfer, antibody therapy and dendritic cell therapy had variable success in generating primary anti-tumor responses. [1–5] [6–9] [10] [11] However, all failed to generate robust acquired immunity and memory T-cells targeted towards tumors, likely due to the inability to provide appropriate inflammatory stimuli, so called “danger signals”, within the tumor microenvironment. Additionally, effective therapy must overcome multiple mechanisms used by tumors to inhibit antigen-specific immunity including regulatory T-cells (Treg) and inhibitory co-receptor signaling.

Previously, we utilized a genetically attenuated strain of Listeria monocytogenes (with deletion of both actin A and internalin B genes, referred to as LMD), a gram positive bacterium, in a model of hepatic colorectal cancer metastases. We found that LMD generated strong innate anti-tumor immune responses through activation of NK and NKT cells. A smaller contribution to anti-tumor effects resulted from cytotoxic CD8+T-cells with an interferon-γ dominant helper T-cell (Th1) phenotype. [12–14] We developed a new strain of LMD, expressing AH1 (LMD-AH1), the tumor-associated immunodominant antigen of the murine colon cancer cell line, CT26 in order to increase recruitment of the adaptive immune response. [15, 16] Recently, LM was shown to elicit antigen-specific CD8+T-cell responses when used as a vaccine vector in breast and ovarian cancer models. [17–19] Utilizing this strategy, we elicited strong cytotoxic tumor specific CD8+T-cell responses directly within the liver tumor microenvironment, and achieved lasting cure. We also demonstrated that treatment diminished the expression of PD-1, a key immune checkpoint co-inhibitory receptor in CD8+T-cell–dendritic cell interactions. This receptor, when expressed on T-cells, renders tumor infiltrating lymphocytes anergic. [20–22] We also observed the generation of a tumor antigen-specific pool of both central and effector memory T-cells in treated mice that survived tumor challenge, with a subsequent expansion of effector memory CD8+T-cells in those mice able to reject tumor re-challenge.

Methods

Animals, Tumor Cell Line and Peptides

BALB/c mice (6–8 weeks old, female) were purchased from the National Cancer Institute and were treated in compliance with the Johns Hopkins Animal Care and Use Committee. CT26 cancer cells [15] were grown in RPMI 1640 medium with 10% heat-inactivated FCS (HyClone), 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 2 mM L-glutamine, nonessential amino acids (1% of 100× stock), penicillin (100 U/mL), streptomycin (100 U/mL) and 3 μL β-mercaptoethanol. AH1 (SPSYVYHQF), a H-2Ld-restricted peptide and β-gal (TPHPARIGL) control peptide, [23] were synthesized by the Johns Hopkins University Protein/Peptide/DNA facility with 99% purity.

Listeria monocytogenes

LMD was provided by Aduro BioTech. [14, 24] The AH1 peptide expressing strain (LMD-AH1) was constructed from the LMD strain with the AH1 sequence inserted into the gene encoding the actin A-Ovalbumin fusion protein with oligonucleotide directed PCR. The construct was cloned into the pPL2 integration vector and integrated at the tRNA Arg locus of the bacterial chromosome. [25] Molecular constructs were confirmed by sequencing.

Murine hepatic metastasis model and treatment

Mice were given isolated hepatic metastases using a hemispleen injection technique (Supplementary Figure 1). [26] Treatment doses of LMD or LMD-AH1 were administered i.p. every three days at a dose equivalent to1/10 the experimentally determined lethal dose (0.1× LD50). A dose of 50mg/kg of cyclophosphamide (Sigma St. Louis, Missouri) was given i.p. [27]

Analysis and isolation of splenic and liver infiltrating lymphocytes

Lymphocytes from livers and spleens were isolated and processed as per Yoshimura et al. 2007. [14] After isolation, cells were blocked with Fcγ III/II R Antibody (BD PharMingen) and stained with commercially available CD3, CD4, CD8, CD62L, CD95, PD-1(eBioscience). Intracellular staining of CTLA-4 or Foxp3 was done with an intracellular cytokine kit (eBioscience) and analyzed on a FACS Calibur flow cytometer. After lymphocyte isolation 1:1000 of Golgistop (BD Biosciences) and 20 μg/ml of AH1 or β-gal peptide were added (2:1000) and co-incubated at 37 °C for 5 hours followed by intracellular staining with interferon-γ (BD PharMingen). Tetramer staining was performed on liver infiltrating lymphocytes after using magnetic bead CD8+ T-cell isolation (Milteny Biotec) and stained with an AH1 or β-gal specific Ld tetramer, provided by Jill Slansky.

In vivo CTL assay

In vivo cytotoxic activity of antigen-specific T-cells was assayed as previously described. [28] The CFSEhi-labeled cells were pulsed with 10μg/ml (1:1000) of AH1 peptide, and CFSElow-labeled cells were pulsed with 10μg/ml β-gal control peptide. Forty hours after injection of the CFSE-labeled targets cells, the ratio of CFSElow to CFSEhi cells was determined by flow cytometry.

Subcutaneous flank and pulmonary metastases CT26 tumor challenge

For primary challenge and re-challenge experiments, mice were injected with 1×105 CT26 cells subcutaneously. Tumor volume was calculated as 0.5 (A × B2), with B = the smaller diameter. Pulmonary metastases were given via tail vein injection with 5×104 for primary challenge or 1×105 CT26 cells for re-challenge experiments.

AH1 Antigen-Specific CD8 Memory T-cell analysis

Hepatic metastases survivors from each treatment group and tumor naïve mice underwent partial splenectomy. Splenic lymphocytes underwent AH1 specific tetramer and extracellular staining for CD8, CD62L and CD95 (eBioscience). After 3 days, mice received a flank injection of CT26 tumor cells and eight days later, underwent completion splenectomy with repeat staining.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism Version 5.0. Log-rank analysis was performed for survival experiments. Mann-Whitney was used for analysis of the AH1 antigen-specific memory CD8+ T-cell experiment. 2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post test analysis was performed for all other analyses. A p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All experiments were repeated 3 times and representative results of each experiment are shown.

Results

Tumor associated antigen expressing Listeria monocytogenes (LMD-AH1) has enhanced anti-tumor efficacy against CT26 metastases

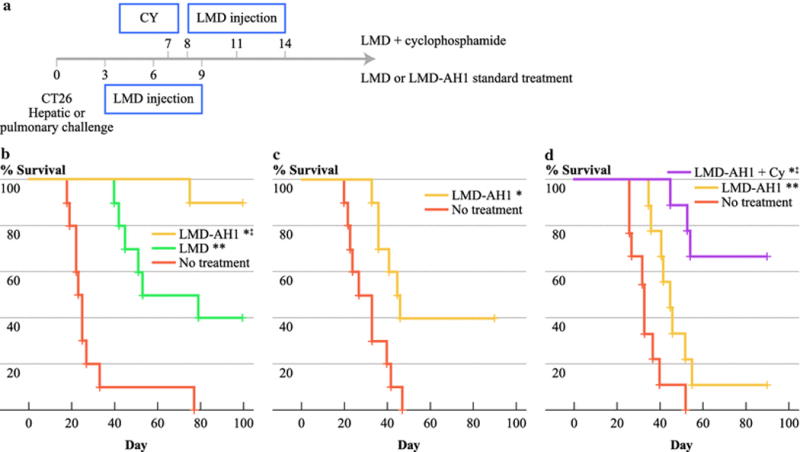

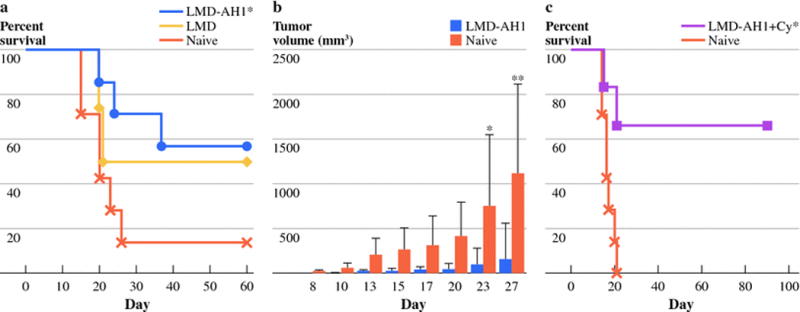

The therapeutic effect of LMD-AH1 was compared to treatment with LMD or no treatment (NT) after hepatic metastases tumor challenge. Mice treated with LMD-AH1 exhibited 90% survival (p=0.016 vs. LMD and p<0.001 vs. NT) compared with 40% survival for mice treated with LMD (p=0.002 vs. NT) (Figure 1b), consistent with our previously published reported efficacy for LMD. [14, 26]

Figure 1.

Treatment with tumor antigen expressing Listeria (LMD-AH1) improves survival. a) Treatment protocol for parts b–d. b) Balb/c mice were treated with injections of 0.1×LD50 of LMD-AH1 or LMD on days 3, 6 and 9 after CT26 tumor challenge on day 0 with hemi-splenectomy liver metastases model. N=10 per group. Log-rank test *p<0.001 LMD-AH1 vs. NT; ‡p= 0.016 LMD-AH1 vs. LMD; **p= 0.002 LMD vs. NT. c) Balb/c mice were treated with LMD-AH1 or LMD on days 3, 6 and 9 after CT26 tumor challenge via tail vein injection. N=10 per group. Log-rank test *p= 0.011. d) Mice were treated with cyclophosphamide (Cy) on Day 7 followed with LMD-AH1 on Day 8, 11, 14 or LMD-AH1 alone. N=10 per group. Log-rank test ‡p= 0.006 LMD-AH1 + Cy vs. LMD-AH1; *p<0.001 LMD-AH1+ Cy vs. NT; **p= 0.013 LMD-AH1 vs. NT.

In our initial work, when mice were challenged with CT26 pulmonary metastases and treated with the LMD strain, no mice survived, likely due to a lack of a systemically generated effector CD8+T-cell response. However, after tail vein injection, 40% of mice treated with LMD-AH1 survived (p= 0.011) (Figure 1c). This finding was corroborated by Brockstedt et al. [24] who used an AH1-A5 peptide expressing strain of LMD to achieve a survival benefit after intravenous CT26 challenge. Of note in both the liver and pulmonary metastases model, at the time of completion of the survival experiment, mice that were alive showed no evidence of disease, while those which died earlier all had evidence metastatic disease.

Because Tregs represent a critical inhibitor of tumor immunity, the expression of Foxp3 on CD4+T-cells was studied within the tumor microenvironment in the liver and on splenocytes. Increased numbers of Foxp3+ Tregs were present in all tumor challenged groups (Supplementary Figure 3). Given these findings, we attempted to improve survival of LMD-AH1 treated mice by combining treatment with a Treg inhibitory dose of cyclophosphamide. We previously demonstrated efficacy when combining cyclophosphamide and LMD in a low tumor burden model due to the depletion of Treg cells and a subsequent improvement in the numbers and activation of antigen-specific CD8+ T-cells. [14] Given the improved efficacy of the LMD-AH1 strain, we waited until a higher tumor burden (macroscopic disease) was present before beginning treatment. Mice given a single dose of 50mg/kg of cyclophosphamide (Cy) on day 7 followed by LMD-AH1 on days 8, 11 and 14 had 60% survival, compared with 10% for LMD-AH1 alone (p= 0.006 LMD-AH1 + Cy vs. LMD-AH1; p<0.001 LMD-AH1+ Cy vs. NT; p=0.013 LMD-AH1 vs. NT) (Figure 1d).

Mice treated with LMD-AH1 have a sustained increase in antigen-specific CD8+T-cells

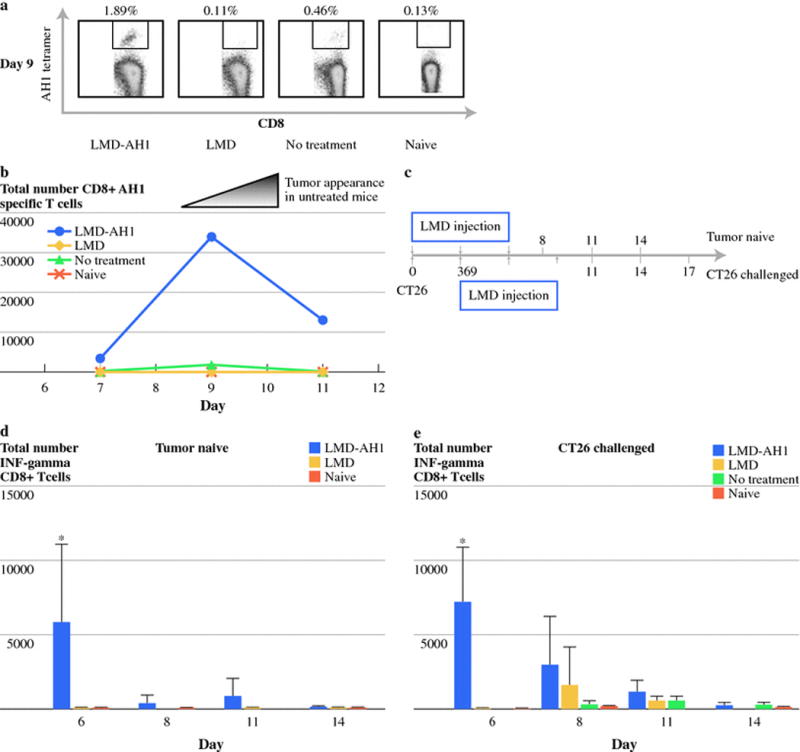

In order to assess tumor antigen-specific CD8+T-cells, we stained isolated liver lymphocytes with an AH1 peptide loaded Ld tetramer. Those treated with LMD-AH1 had the highest percentage of CD8+AH1 specific T-cells (1.89%) compared with LMD (0.11%), NT (0.46%), or naïve (0.13%) (Figure 2a). The peak on Day 9 was followed by a lower but steady population through day 11 for LMD-AH1 treated mice (Figure 2b). In contrast, no discernable peak and a small number of antigen-specific CD8+T-cells were found in groups treated with LMD or that received no treatment.

Figure 2.

Mice treated with LMD-AH1 have a high number and sustained population of antigen-specific CD8+ T-cells with interferon-γ activity. a) Percentage of AH1-specific CD8+ T-cells on Day 9 in the liver. N=3 mice pooled per group. b) Total number of AH1-specific CD8+ T-cells on days 7, 9 and 11. c) Diagrammatic representation of Listeria injection schedule of Tumor Naïve mice compared with CT26 Challenged mice. d) Total number of CD8+ T-cells harvested from the liver from Tumor Naïve or CT26 Challenged mice with intracellular staining for interferon-γ after AH1 peptide stimulation. N= 3 mice per group. 2-way ANOVA Bonferronni post test *p<0.001 LMD-AH1 vs. LMD and Naive for Day 6 for Tumor Naïve mice. 2-way ANOVA Bonferronni post test *p<0.001 LMD-AH1 vs. LMD, NT and Naive for Day 9 for CT26 challenged mice. p= ns unless otherwise noted above.

Both tumor bearing and non-tumor bearing mice treated with LMD-AH1 have higher interferon-γ expression in CD8+T-cells

We hypothesized that treatment with LMD-AH1, even in a tumor naïve mouse, would activate CD8+T-cells and direct an antigen-specific adaptive immune response measured by ex-vivo stimulation with the AH1 peptide. Tumor naïve mice were injected with LMD or LMD-AH1 and CD8+T-cell interferon-γ production was measured by intracellular staining. On Day 6 (Figure 2d), mice treated with LMD-AH1 had more antigen-specific CD8+T-cell interferon-γ expression (p<0.001 LMD-AH1 vs. LMD, NT and Naive). Similar results were seen when tumor challenged mice were treated with LMD-AH1 (Figure 2d) with peak interferon-γ activity observed on Day 9 after tumor challenge (p<0.001 LMD-AH1 vs. LMD, NT and Naïve). These findings also correspond to the peak time of antigen-specific CD8+T-cells found on tetramer staining. Mice treated with LMD alone had a later and smaller peak on day 11 while NT mice lacked interferon-γ production, similar to non-tumor bearing naïve mice. Interestingly, when interferon-γ production from CD4+T-cells was examined, there were no differences between LMD-AH1 or LMD treated mice, and only slight increases when compared to NT or naïve mice (data not shown). When IL-17 expression was examined on CD4+ T-cells, no differences were seen between any groups (data not shown).

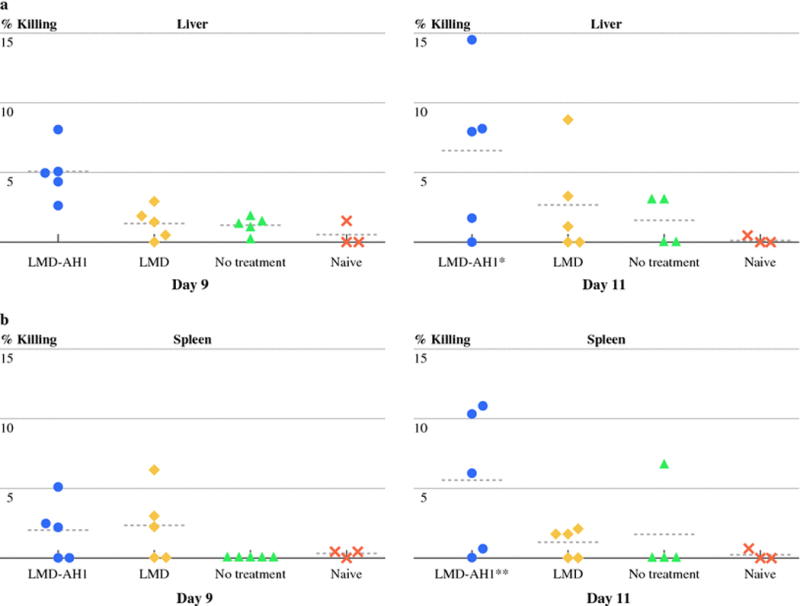

Tumor specific CD8+ T-cells isolated from the livers and spleens of mice treated with LMD-AH1 have the highest cytotoxic killing ability

To measure functional differences between lymphocytes from mice treated with LMD-AH1, in vivo CTL assays were performed on Day 9 and 11 after hepatic tumor challenge. In Figure 3a, the mean percent killing was highest for LMD-AH1 on days 9 and 11 (5.05% and 6.05%) (p<0.05 for LMD-AH1 vs. NT and Naïve). In the spleen (Figure 3b), mean percent killing was again highest for the LMD-AH1 group on both days peaking on Day 11 (1.96% and 5.59%) (p<0.05 for LMD-AH1 vs. LMD; LMD-AH1 vs. Naïve). Again, as significant targeted killing was seen for LMD-AH1 treated mice, these results are consistent with the presence of a robust, activated population of immune cells.

Figure 3.

Mice treated with LMD-AH1 have the highest cytotoxic activity in in vivo cytotoxic T-cell assay. Mice (N=5 per group per day) were challenged with hepatic metastases and treated with LMD or LMD-AH1 on day 3, 6, 9. On day 9 or 11 mice were injected with CFSE high labeled cells pulsed with AH1 peptide and CFSElow labeled cells pulsed with β-gal peptide. a) Livers or b) Spleens were harvested and the ratio of CFSE high/low was used to determine % killing by flow cytometry. Shown are individual data points with a horizontal line representing the mean. 2-way ANOVA Bonferroni post test *p<0.05 for LMD-AH1 vs. NT and Naïve in the liver and **p<0.05 for LMD-AH1 vs. LMD; LMD-AH1 vs. Naïve in the spleen. p= ns unless otherwise noted above.

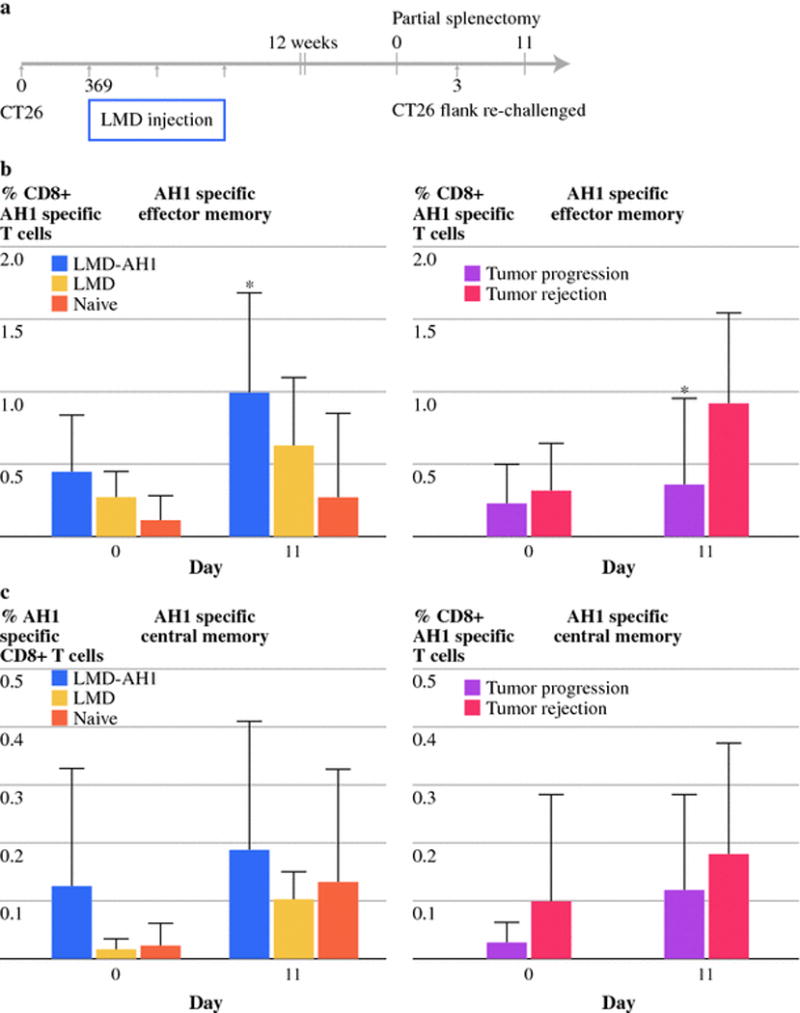

Treatment with LMD-AH1 leads to long term antigen-specific memory and immunity from tumor re-challenge

After 12 weeks, mice that survived initial tumor challenge and treatment with LMD-AH1, LMD, or tumor naïve mice underwent partial splenectomy. CD8+AH1 tetramer specific effector (CD62Llow CD95high) and central (CD62Lhigh CD95high) memory T-cells were identified before and following flank challenge with CT26. At both time points, higher percentages of both AH1 specific central and effector memory T-cells were found in mice previously treated with LMD-AH1 (LMD-AH1 vs. Naïve p<0.05 on day 11) (Figure 4b–c). When mice were stratified by presence or absence of tumor growth, by Day 11, mice which rejected tumor had higher numbers of AH1specific effector memory CD8+T-cells (p=0.027) and trended towards a greater number of AH1 specific central memory CD8+T-cells (Figure 4b–c). Importantly, this effect was antigen-specific because when total central and effector memory CD8+T-cell populations were examined there were no differences between treatment groups and no correlation between the absolute number of memory cells and whether the tumor was rejected (Supplementary Figure 3).

Figure 4.

Treatment with LMD-AH1 promotes tumor antigen-specific immunologic memory. a) Experimental design for parts b–c. Values of the percent of b) CD8+ AH1-specific effector memory (CD62L low CD95 high) or c) central memory (CD62L high CD95 high) T-cells are shown by treatment group or as a function of tumor progression or rejection. N=7 LMD-AH1, N=5 LMD, N=8 Naïve. 2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post test *p<0.05 for LMD-AH1 vs. Naïve on Day 11 and Mann-Whitney *p= 0.027 on Day 11 for percent of tumor antigen-specific CD8+ effector memory T-cells. Data for central memory p= ns.

In order to further assess the generation of systemic memory responses after initial rejection of hepatic metastases, animals treated with LMD-AH1 (n=7) or LMD (n=4) that survived 125 days after hepatic tumor challenge were given a re-challenge with 1×105 CT26 cells via tail vein injection. Previously treated LMD-AH1 mice had 57% survival vs. 50% with LMD and 14% in the tumor naïve group (p=0.044) (Figure 5a). Mice treated with LMD-AH1 that survived 110 days after initial hepatic metastases challenge were re-challenged with 1×105 CT26 tumor cells subcutaneously on the flank (Figure 5b) and by Day 27, 6/7 mice previously treated with LMD-AH1 rejected tumor vs. 1/7 naïve mice (p<0.001). When mice given liver metastases that underwent late treatment with LMD-AH1 with cyclophosphamide were re-challenged, 67% survived (p< 0.01) (Figure 5c).

Figure 5.

Treatment with LMD-AH1 protects against tumor re-challenge. a) On day 125, previously treated survivors of hepatic metastases were re-challenged with CT26 pulmonary metastases and survival was compared to tumor naïve mice. N=7 LMD-AH1, Naive group. N=4 LMD. Log-rank test *p= 0.044 for LMD-AH1 vs. Naïve. b) On day 110, survivors of hepatic metastases previously treated with LMD-AH1 were re-challenged with CT26 cells given through a subcutaneous flank injection and tumor volume was compared to tumor naïve mice. N=7 for LMD-AH1 group and N=6 for NT group. 2-way ANOVA p= 0.034 with Bonferroni post test *p<0.05 on Day 23 and **p<0.001 on Day 27. c) On day 140 after hepatic metastases challenge, survivors previously treated with LMD-AH1 + cyclophosphamide were re-challenged with CT26 pulmonary metastases. N=6 LMD-AH1 + Cy, N=7 Naïve. Log-rank *p<0.01. p= ns unless otherwise noted above.

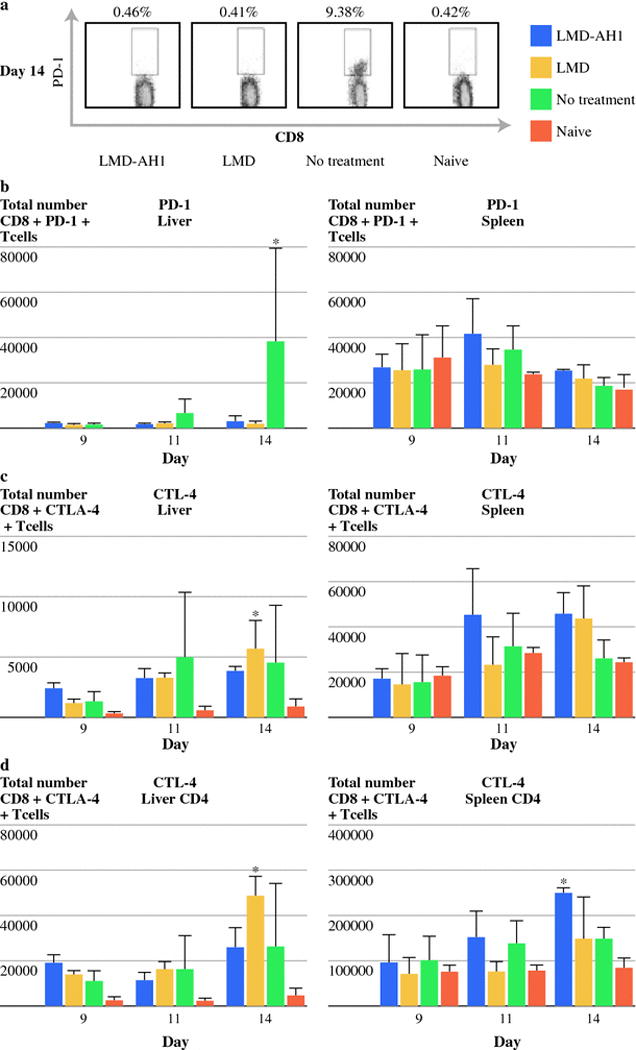

Treatment with L. monocytogenes affects PD-1 and CTLA-4 expression on CD8+T-cells in mice with hepatic metastases

PD-1 and CTLA-4 are co-receptors expressed on exhausted CD8+T-cells and have been found to be present in large numbers in the tumor microenvironment and are also found in chronically infected animals, rendering CD8+T-cells anergic. As LMD is known to cause inflammation we wanted to characterize any change in the expression of these receptors. CD8+T-cells in the spleen showed little difference in PD-1 expression between any group even with increasing tumor burden (p= ns) (Figure 6b). However, in the liver, NT mice showed an increase in both the percentage and absolute number of CD8+ T-cell PD-1 expression over time, peaking at day 14, mirroring the increase in tumor burden (Figure 6a,b). In groups treated with either LMD or LMD-AH1, little to no increase in PD-1 expression was observed (p < 0.01 NT vs. LMD-AH1, LMD and Naïve in liver on Day 14) (Figure 6b).

Figure 6.

Listeria has differential effects on co-receptor expression in tumor bearing mice. a) Listeria does not cause an upregulation of PD-1 expression on CD8+ T-cells. Representative data shown of CD8+ T-cells expressing PD-1 on Day 14 in the liver. b) Total CD8+ T-cell PD-1 expression in the liver and spleen. *p<0.01 NT vs. LMD-AH1, LMD and Naïve in liver on Day 14. c) Total number of CD8+ T-cells expressing the co-receptor CTLA-4 *p<0.05 LMD vs. Naïve in liver and spleen. d) Total number CD4+ T-cells expressing CTLA-4 *p<0.05 LMD vs. LMD-AH1 and NT; **p<0.05 Naïve vs. LMD-AH1, LMD and NT in liver and *p<0.05 LMD-AH1 vs. LMD, NT and Naïve in spleen. N=3 mice per group per day. p= ns unless otherwise noted above.

CTLA-4 expression was measured on CD8+T-cells, but when compared to naïve mice, all tumor challenged groups had higher levels of expression despite no group reaching a statistical significant increase in expression (Figure 6c). However, consistent with findings by Rowe, et al. in a primary attenuated LM infection study, [29] overall CTLA-4 expression on CD4+T-cells was found to be much higher than on CD8+ T-cells in the liver and spleen (Figure 6d). In the liver, all groups had higher expression of CTLA-4 than naïve mice, with LMD reaching statistically significant expression on Day 14 (p<0.05) (Figure 6d). On Day 14, CTLA-4 expression in the spleens of mice treated with LMD-AH1 had the highest expression among all groups although overall the differences in the spleen were less dramatic (p<0.05). As CTLA-4 expression was increased in the liver tumor microenvironment, blockade of CTLA-4 would be a target to be used in combination with attenuated LM.

Discussion

Even with advances in liver directed therapies for the treatment of hepatic colorectal metastases, hepatic tumor burden is often rate limiting. We previously described treatment with non-antigen expressing LMD as an immunotherapeutic treatment for this disease, which could be enhanced either by the depletion of regulatory T-cells with cyclophosphamide [14] or in combination with a GM-CSF secreting cancer vaccine. [26] In our current study, we demonstrated that use of tumor antigen expressing LMD is more effective in generating an initial effector response by producing AH1 antigen-specific CD8+T-cells in greater numbers than a doubly attenuated strain alone. Furthermore, the activation, as measured by interferon-γ, and the killing ability of these CD8+T-cells, as shown in the in vivo CTL assay, in both the local tumor environment within the liver and in the systemic circulation were both augmented. In contrast to previous work, this antigen expressing strain was able to enhance survival in both a primary lung and flank tumor challenge study despite the hepatotropic nature of LM. Additionally, LMD-AH1 in combination with cyclophosphamide could cure mice with far greater tumor burden (macroscopic disease) whereas LMD with cyclophosphamide previously cured just microscopic disease [14].

Both the development of an initial response which eradicates the primary tumor burden and the development of an antigen-specific memory response are important for long term survival. Although AH1 specific CD8+ memory T cells are initially generated by either form of the vaccine, LMD or LMD-AH1, Figures 1–3 show the reliability and overall generation of the initial tumor specific CD8+ T cells was superior in LMD-AH1 treated mice. Mice treated with LMD-AH1 were not only able to survive the original hepatic tumor challenge, but were also able to reject tumor when re-challenged in previously tumor naïve sites.

In order to specifically investigate the formation of these antigen-specific memory T-cells, we developed a novel technique utilizing repeated surgical intervention. A portion of the spleen was resected before and after tumor re-challenge, giving us a large number of lymphocytes to detect antigen specific T-cells, which was not technically possible by using circulating blood or other sources. This technique also allowed us to not only to quantify the baseline antigen-specific total effector and central memory populations but also to see whether a change in this response occurred and if this was crucial for tumor rejection. Our data indicate that the presence of higher tumor specific central and effector memory CD8+T-cell populations was associated with tumor eradication and that antigen-specific effector memory cells underwent expansion.

The development of memory T-cells and the magnitude of cells needed for in vivo responses remain controversial. However, these pathways involve both internal and external stimuli within an inflammatory background with signaling from CD4+T-cells and cytokines released by APCs [30–32]. When LM was used in another experimental model and compared with adenoviral vectors for tumor antigen delivery, LM showed enhanced memory responses. [33] Although this phenomenon may be specific to certain tumor microenvironments, our data supports the liver as a site where the generation of a strong antigen-specific memory response may be dependent on the generation of a Th1 background. [33] We were able to show that although our treatment causes inflammation, it did not induce a Th17-like background which has been implicated in tumor progression. Additionally, the memory responses shown in our work are both durable and specific as they persist without the need to boost or re-prime the immune system.

Interestingly, a decrease in the expression of PD-1+CD8+T-cells was observed in mice treated with LMD-AH1. This decrease in PD-1 expression may be either due to the decreased tumor burden causing less induction of PD-1 on tumor infiltrating lymphocytes or possibly may be the direct product of the attenuated LM itself through cytokine signaling. LM may also lead to changes in PD-1 expression through modulation of PD-1’s receptors, B7-H1 and B7-DC, in the tumor microenvironment. The combination of LM with blockade of PD-1 or its receptors may be a viable treatment approach.

Although we saw less expression of PD-1, a treatment associated decrease in another immune checkpoint receptor, CTLA-4 was not found in our study. To the contrary, we found an increase in CTLA-4 expression on both CD4+ and CD8+T-cell populations in all groups challenged with tumor regardless of treatment amongst liver lymphocytes, while little difference was found in the spleen. Given the differences between CTLA-4 and PD-1 in their location and temporal expression, these pathways may be differentially affected by our treatment. [34, 35] The increased CTLA-4 expression is significant because just as the presence of tumor led to an increase in Foxp3+Tregs, providing a target for combinatorial treatment with cyclophosphamide, one could hypothesize that CTLA-4 would be an additional candidate for blockade when using our vaccine. This hypothesis is supported by findings by Rowe, et al. [30] and Pedicord, et al. [37] Rowe, et al [29] showed that blockade of CTLA-4 led to augmented antigen-specific CD4+ and CD8+T-cell responses directed towards an attenuated strain of LM during primary infection. Peticord et al.[36] reported that a single dose of anti-CTLA-4 antibody when administered with Listeria monocytogenes, enhanced bacterial clearance upon re-challenge due to an increase in the production of effector memory T cells. Conceivably, the blockade of CTLA-4 could increase antigen-specific responses to tumor-associated antigens delivered by LM allowing for stronger initial anti-tumor responses or for smaller doses of antigen expressing LM to be administered, thus increasing the safety profile with the use of this bacterium. The initial enhanced response combined with increased effector memory T cells, could not only lead to improved initial tumor eradication but also to the prevention of recurrent disease.

Although the identification of cancer associated antigens for targeted therapies has progressed, any successful treatment will need to overcome the barriers presented by MHC I downregulation, and co-receptor signaling between tumor cells, T-cells and APCs leading to continued immune evasion. In our study, the efficacy shown using this genetically attenuated strain of AH1 expressing LM suggests that it can be engineered to synthesize a sufficient amount of tumor associated antigen through a strong promoter. Additionally, other groups have shown that LM can be engineered to express polyvalent tumor specific antigens. [19, 37] Despite this, advances in genetic engineering of LM are needed to determine the relative importance of virulence factors to enable toll-like receptor signaling while maintaining the ability to reliably deliver antigen.

In summary, we have shown that tumor-associated antigen expressing, genetically attenuated Listeria monocytogenes used in a murine model of colorectal cancer metastasis is effective to initially treat and subsequently prevent tumor recurrence. This efficacy was demonstrated by inducing three major immune mechanisms including innate, adaptive and tumor specific immune memory. The success in this pre-clinical model continues to show the promise to develop LM based treatment platforms into effective vaccines in human clinical trials and to find novel combinatorial regimens to further enhance its observed efficacy.

Supplementary Material

a) Subcostal incision made and spleen exposed. b) Spleen divided between vascular clips and divided. c) Tumor cells slowly injected into hemi-spleen. d) Splenic vessels divided. e) Tumor injected hemi-spleen resected. f) Peritoneum and skin closed.

Supplementary Figure 2. Foxp3+ CD4+ T-cell populations expressing targets for future combinatorial treatment. Total number of CD4+ T-cells expressing Foxp3 *p<0.001 NT vs. Naïve; **p<0.05 LMD vs. Naïve in spleen on days 11, 14, 17 following hepatic metastases challenge. N=3 mice per group per day. p= ns unless otherwise noted above.

Supplementary Figure 3. Total effector and central memory T-cells a) Experimental design. b, c) Values of the percent of CD8+ effector memory (CD62L low CD95 high) or d, e) central memory (CD62L high CD95 high) T-cells are shown by treatment group or as a function of tumor progression or rejection. N=7 LMD-AH1, N=5 LMD, N=8 Naïve. p= ns.

Synopsis.

A genetically attenuated strain of Listeria monocytogenes expressing a tumor-associated antigen elicits innate, adaptive and tumor specific immune memory to eradicate hepatic metastases. Success in this pre-clinical model supports translational human clinical trials utilizing this bacterium.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: NIH grants T32 DK007713-14 (Kelly Olino), K23 CA104160 (Richard Schulick), R01 CA112160 (Kiyoshi Yoshimura), Swiss National Science Foundation PBBSB-118840 (Walter Weber). Peter Lauer and Dirk Brockstedt are employees of Aduro BioTech which develops Listeria monocytogenes based vaccines. Drew Pardoll, Richard Schulick, Kiyoshi Yoshimura and Dirk Brockstedt hold a patent on Listeria-induced immunorecruitment and activation, and methods of use thereof.

References Cited

- 1.Hueman MT, Dehqanzada ZA, Novak TE, et al. Phase I clinical trial of a HER-2/neu peptide (E75) vaccine for the prevention of prostate-specific antigen recurrence in high-risk prostate cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:7470–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jaffee EM, Hruban RH, Biedrzycki B, et al. Novel allogeneic granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor-secreting tumor vaccine for pancreatic cancer: a phase I trial of safety and immune activation. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:145–56. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.1.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson LE, Frye TP, Arnot AR, Marquette C, Couture LA, Gendron-Fitzpatrick A, McNeel DG. Safety and immunological efficacy of a prostate cancer plasmid DNA vaccine encoding prostatic acid phosphatase (PAP) Vaccine. 2006;24:293–303. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.07.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peoples GE, Holmes JP, Hueman MT, et al. Combined clinical trial results of a HER2/neu (E75) vaccine for the prevention of recurrence in high-risk breast cancer patients: U.S. Military Cancer Institute Clinical Trials Group Study I-01 and I-02. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:797–803. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramanathan RK, Lee KM, McKolanis J, et al. Phase I study of a MUC1 vaccine composed of different doses of MUC1 peptide with SB-AS2 adjuvant in resected and locally advanced pancreatic cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2005;54:254–64. doi: 10.1007/s00262-004-0581-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Araki A, Hazama S, Yoshimura K, Yoshino S, Iizuka N, Oka M. Tumor secreting high levels of IL-15 induces specific immunity to low immunogenic colon adenocarcinoma via CD8+ T cells. International journal of molecular medicine. 2004;14:571–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kawaoka T, Oka M, Takashima M, et al. Adoptive immunotherapy for pancreatic cancer: cytotoxic T lymphocytes stimulated by the MUC1-expressing human pancreatic cancer cell line YPK-1. Oncology reports. 2008;20:155–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kondo H, Hazama S, Kawaoka T, et al. Adoptive immunotherapy for pancreatic cancer using MUC1 peptide-pulsed dendritic cells and activated T lymphocytes. Anticancer research. 2008;28:379–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoshimura K, Hazama S, Iizuka N, et al. Successful immunogene therapy using colon cancer cells (colon 26) transfected with plasmid vector containing mature interleukin-18 cDNA and the Igkappa leader sequence. Cancer gene therapy. 2001;8:9–16. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dudley ME, Yang JC, Sherry R, et al. Adoptive cell therapy for patients with metastatic melanoma: evaluation of intensive myeloablative chemoradiation preparative regimens. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5233–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.5449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hodi FS, Mihm MC, Soiffer RJ, et al. Biologic activity of cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 antibody blockade in previously vaccinated metastatic melanoma and ovarian carcinoma patients. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100:4712–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0830997100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan CW, Crafton E, Fan HN, et al. Interferon-producing killer dendritic cells provide a link between innate and adaptive immunity. Nature medicine. 2006;12:207–13. doi: 10.1038/nm1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pletneva M, Fan H, Park JJ, et al. IFN-producing killer dendritic cells are antigen-presenting cells endowed with T-cell cross-priming capacity. Cancer research. 2009;69:6607–14. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoshimura K, Laird LS, Chia CY, et al. Live attenuated Listeria monocytogenes effectively treats hepatic colorectal cancer metastases and is strongly enhanced by depletion of regulatory T cells. Cancer research. 2007;67:10058–66. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Griswold DP, Corbett TH. A colon tumor model for anticancer agent evaluation. Cancer. 1975;36:2441–4. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197512)36:6<2441::aid-cncr2820360627>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Corbett TH, Griswold DP, Jr, Roberts BJ, Peckham JC, Schabel FM., Jr Tumor induction relationships in development of transplantable cancers of the colon in mice for chemotherapy assays, with a note on carcinogen structure. Cancer research. 1975;35:2434–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim SH, Castro F, Paterson Y, Gravekamp C. High efficacy of a Listeria-based vaccine against metastatic breast cancer reveals a dual mode of action. Cancer research. 2009;69:5860–6. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seavey MM, Pan ZK, Maciag PC, Wallecha A, Rivera S, Paterson Y, Shahabi V. A novel human Her-2/neu chimeric molecule expressed by Listeria monocytogenes can elicit potent HLA-A2 restricted CD8-positive T cell responses and impact the growth and spread of Her-2/neu-positive breast tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:924–32. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sinnathamby G, Lauer P, Zerfass J, et al. Priming and Activation of Human Ovarian and Breast Cancer-specific CD8+ T Cells by Polyvalent Listeria monocytogenes-based Vaccines. J Immunother. 2009;32:856–69. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181b0b125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Francisco LM, Salinas VH, Brown KE, Vanguri VK, Freeman GJ, Kuchroo VK, Sharpe AH. PD-L1 regulates the development, maintenance, and function of induced regulatory T cells. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2009 doi: 10.1084/jem.20090847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Freeman GJ, Long AJ, Iwai Y, et al. Engagement of the PD-1 immunoinhibitory receptor by a novel B7 family member leads to negative regulation of lymphocyte activation. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2000;192:1027–34. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.7.1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sharpe AH, Wherry EJ, Ahmed R, Freeman GJ. The function of programmed cell death 1 and its ligands in regulating autoimmunity and infection. Nature immunology. 2007;8:239–45. doi: 10.1038/ni1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang AY, Gulden PH, Woods AS, et al. The immunodominant major histocompatibility complex class I-restricted antigen of a murine colon tumor derives from an endogenous retroviral gene product. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1996;93:9730–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brockstedt DG, Giedlin MA, Leong ML, et al. Listeria-based cancer vaccines that segregate immunogenicity from toxicity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:13832–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406035101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lauer P, Chow MY, Loessner MJ, Portnoy DA, Calendar R. Construction, characterization, and use of two Listeria monocytogenes site-specific phage integration vectors. Journal of bacteriology. 2002;184:4177–86. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.15.4177-4186.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yoshimura K, Jain A, Allen HE, et al. Selective targeting of antitumor immune responses with engineered live-attenuated Listeria monocytogenes. Cancer research. 2006;66:1096–104. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wada S, Yoshimura K, Hipkiss EL, et al. Cyclophosphamide augments antitumor immunity: studies in an autochthonous prostate cancer model. Cancer research. 2009;69:4309–18. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mueller SN, Jones CM, Smith CM, Heath WR, Carbone FR. Rapid cytotoxic T lymphocyte activation occurs in the draining lymph nodes after cutaneous herpes simplex virus infection as a result of early antigen presentation and not the presence of virus. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2002;195:651–6. doi: 10.1084/jem.20012023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rowe JH, Johanns TM, Ertelt JM, Lai JC, Way SS. Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 blockade augments the T-cell response primed by attenuated Listeria monocytogenes resulting in more rapid clearance of virulent bacterial challenge. Immunology. 2009;128:e471–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.03001.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Janssen EM, Lemmens EE, Wolfe T, Christen U, von Herrath MG, Schoenberger SP. CD4+ T cells are required for secondary expansion and memory in CD8+ T lymphocytes. Nature. 2003;421:852–6. doi: 10.1038/nature01441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Obar JJ, Molloy MJ, Jellison ER, Stoklasek TA, Zhang W, Usherwood EJ, Lefrancois L. CD4+ T cell regulation of CD25 expression controls development of short-lived effector CD8+ T cells in primary and secondary responses. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909945107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stemberger C, Huster KM, Koffler M, Anderl F, Schiemann M, Wagner H, Busch DH. A single naive CD8+ T cell precursor can develop into diverse effector and memory subsets. Immunity. 2007;27:985–97. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stark FC, Sad S, Krishnan L. Intracellular bacterial vectors that induce CD8(+) T cells with similar cytolytic abilities but disparate memory phenotypes provide contrasting tumor protection. Cancer research. 2009;69:4327–34. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fife BT, Bluestone JA. Control of peripheral T-cell tolerance and autoimmunity via the CTLA-4 and PD-1 pathways. Immunological reviews. 2008;224:166–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fife BT, Pauken KE, Eagar TN, et al. Interactions between PD-1 and PD-L1 promote tolerance by blocking the TCR-induced stop signal. Nature immunology. 2009;10:1185–92. doi: 10.1038/ni.1790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pedicord VA, Montalvo W, Leiner IM, Allison JP. Single dose of anti-CTLA-4 enhances CD8+ T-cell memory formation, function, and maintenance. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:266–71. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016791108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brockstedt DG, Dubensky TW. Promises and challenges for the development of Listeria monocytogenes-based immunotherapies. Expert review of vaccines. 2008;7:1069–84. doi: 10.1586/14760584.7.7.1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

a) Subcostal incision made and spleen exposed. b) Spleen divided between vascular clips and divided. c) Tumor cells slowly injected into hemi-spleen. d) Splenic vessels divided. e) Tumor injected hemi-spleen resected. f) Peritoneum and skin closed.

Supplementary Figure 2. Foxp3+ CD4+ T-cell populations expressing targets for future combinatorial treatment. Total number of CD4+ T-cells expressing Foxp3 *p<0.001 NT vs. Naïve; **p<0.05 LMD vs. Naïve in spleen on days 11, 14, 17 following hepatic metastases challenge. N=3 mice per group per day. p= ns unless otherwise noted above.

Supplementary Figure 3. Total effector and central memory T-cells a) Experimental design. b, c) Values of the percent of CD8+ effector memory (CD62L low CD95 high) or d, e) central memory (CD62L high CD95 high) T-cells are shown by treatment group or as a function of tumor progression or rejection. N=7 LMD-AH1, N=5 LMD, N=8 Naïve. p= ns.