SUMMARY

Diverse strain types of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) cause infections in community settings worldwide. To examine heterogeneity of spread within households and to identify common risk factors for household transmission across settings, primary data from studies conducted in New York, US, Breda, NL, and Melbourne, AU were pooled. Following MRSA infection of the index patient, household members completed questionnaires and provided nasal swabs. Swabs positive for S. aureus were genotyped by spa-sequencing. Poisson regression with robust error variance was used to estimate prevalence odds ratios for transmission of the clinical isolate to non-index household members. Great diversity of strain types existed across studies. Despite differences between studies, the index patient being colonized with the clinical isolate at the home visit (p<.01) and the percent of household members <18 years (p<.01) were independently associated with transmission. Targeted decolonization strategies could be used across geographic settings to limit household MRSA transmission.

INTRODUCTION

Since the mid-1990’s, methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections have been increasingly encountered in community settings worldwide [1–3]. Multiple dominant clonal lineages have driven this pandemic [4]. Despite such rapid dissemination, it remains unclear how community associated (CA)-MRSA clones spread and become established within communities. Multiple studies conducted across different settings have identified the household as an important reservoir for S. aureus [5–10]. After a household member becomes infected, high levels of S. aureus colonization and infection often occur among other household members [11–15]. Reports have observed that epidemic clones tend to “ping pong” among family members, resulting in a high rate of recurrent infections [16–18]. Eradicating S. aureus from the household and reducing the frequency of these infections has proven difficult [19,20]. A greater understanding of how S. aureus spreads among household members is essential for the design of evidence-based prevention and treatment strategies.

Various studies have examined the spread of S. aureus among households in discrete geographic locations [9,21–24]. These studies have identified various risk factors associated with household transmission in these distinct settings. However, these studies have been limited to analyses of the S. aureus strains that were predominant in those discrete locations. To date, no study has pooled primary data across multiple countries in order to assess the spread of S. aureus in the household setting. Such an analysis would allow for an examination of heterogeneity in the spread of S. aureus among households and identify common risk factors for household transmission across settings and diverse strain types.

In order to assess these issues, we pooled primary data from three studies conducted in New York, United States (US), Breda, the Netherlands (NL), and Melbourne, Australia (AU) [9,10,25]. These studies utilized similar procedures to assess risk factors for household transmission of CA-MRSA among the households of infected cases.

METHODS

POPULATIONS

The current study is a retrospective, observational study that pooled primary data from three cross-sectional studies assessing household transmission of S. aureus [9,10,25]. These studies used similar methods but were conducted across diverse geographic regions, demographically different populations, and featured unique clinical S. aureus strains. The study locations had similar levels of economic development and population access to healthcare. Table 1 provides a comparison of the characteristics of the three studies. One of the studies (US) sampled exclusively from a major metropolitan area, another (AU) sampled from a major metropolitan area and the surrounding suburbs, and the third (NL) sampled from 16 hospitals located throughout the country. In all three studies, a patient with CA-MRSA infection was identified through inpatient and outpatient screening at a hospital (US & NL), or through a community-based private pathology service (AU). In all studies, relevant exclusion criteria were applied to isolate community-associated infections from healthcare-associated infections. Once potential index cases were identified, they were contacted and home visits were scheduled with those who were willing to participate. At the time of the home visit, all household members were asked to participate and provided informed consent. On average, home visits were conducted 61 days (SD = 59) after the infection was cultured.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies in pooled analysis.

| Study Location | United States (US) | Netherlands (NL) | Australia (AU) |

| Study Design | Cross-sectional | Cross-sectional | Longitudinal (only cross-sectional data from baseline used for the current study) |

| Study Setting | Major metropolitan area | Throughout the country | Major metropolitan area and surrounding suburbs |

| Case identification | Inpatient and outpatient screening at a hospital | Inpatient and outpatient screening at 16 hospitals located across the country |

Community-based private pathology service |

| Exclusion criteria |

|

|

|

| Number of cases | N = 139 | N = 61 | N = 96 |

|

Control selection (not included in pooled analyses) |

Uninfected community-based controls | Hospitalized non-MRSA cases | MSSA infected cases |

| Study procedures | Home visit after infection | Home visit after infection | Home visit after infection |

|

Average interval between infection and home visit |

33 days | 43 days | 114 days |

| Interview | Interviewer-administered questionnaire | Interviewer-administered questionnaire | Self-completed questionnaire |

| Risk factor recall period | 6 months prior to infection | 1 year prior to infection | 1 year prior to infection |

| Body sites sampled |

|

|

|

| Strain characterization | Spa-typing | Spa-typing | Spa-typing |

PROCEDURES

The three studies followed similar procedures. At the time of the home visit, all household members who were willing to participate provided swabs from the anterior nares and answered a questionnaire. Anterior nares cultures were collected with sterile swabs from all consenting household members, excluding children <1 year old because of the logistical difficulties of swabbing them. Culture swabs were incubated overnight in high-salt 6.5% broth and plated onto selective media agar for 18–48 hours at 35–37°C. S. aureus was confirmed by coagulase, Protein A detection kit or both. Methicillin resistance was determined by selective media agar, disc diffusion antibiotic sensitivity testing, or PCR was used to test for the presence of Staphylococcal Chromosomal Cassette (SCC)mec. S. aureus positive isolates were genotyped by spa-sequencing [9,10,25–27]. The clinical infection isolates were also retrieved for all index cases. These isolates were obtained from identified sites of infection and underwent the same analyses as all other isolates.

The questionnaires administered in the three studies captured information on a number of risk factors for CA-MRSA acquisition and household transmission. These variables included sociodemographic information (e.g. age, gender, education, income), index patient community exposures (e.g. work, school, daycare, sports participation, travel), health information (recent skin infection, hospital admission, antibiotic use, insulin use), and household characteristics (presence of a pet (dog/cat), presence of children < 18 years old, towel sharing, razor sharing). Variables shared across all three studies were included in statistical analyses. All studies were approved by their respective ethical review boards (US: the Institutional Review Board of Columbia University Medical Center; NL: the medical ethics committee of the St. Elisabeth Hospital in Tilburg; AU: the University of Melbourne Human Research Ethics Committee).

MEASURES

Only risk factors assessed in all studies were included in these analyses. Risk factors were categorized as index patient sociodemographic characteristics (e.g. gender, age, born in country, education), index patient acquisition risk factors (e.g. day care attendance, school attendance, sports participation, international travel), index patient transmission factors (recent skin condition, recent abscess, being colonized with the clinical isolate at the time of the home visit), other household member acquisition risk factors (recent surgery), household transmission risk factors (e.g. presence of a pet (dog/cat), sharing towels, sharing razors), and household sociodemographic characteristics (e.g. household size, percent of children in the household). Acquisition risk factors were considered potential factors that could lead to S. aureus acquisition in the community while transmission risk factors were considered potential factors that could lead to the spread of S. aureus among members of a shared household. In the US study, risk factors were assessed over the previous 6 months. In the NL and AU study, risk factors were assessed over the previous year. Household transmission was defined as colonization of a non-index household member with the same strain spa type as the index patient clinical isolate [28].

STATISTICAL ANALYSES

For comparisons of frequencies of index case and household descriptive data by study, chi-square tests and t-tests were used. In analyses comparing households with evidence of transmission to those without on sociodemographic and risk factor data, Poisson regression models with robust error variance were used to estimate prevalence odds ratios. Prevalence odds ratios (PORs) are reported instead of traditional odds ratios because of the high prevalence of the outcome in our sample (23% (n = 67)) [29–31]. Initially bivariate analyses were run and all variables associated with intra-household S. aureus transmission at P < .20 were considered for inclusion in multivariate analyses strategies [9,32–34]. Once these variables were identified, multivariate analyses were used to model transmission in each individual study and effect estimates were compared to look for heterogeneity of effects across studies. Effect estimates were similar across studies. Heterogeneity of effects across studies was also assessed with meta-analyses for each individual risk factor, using the effect estimates and 95% confidence intervals to generate a summary effect estimate, as well as a Q-statistic, for each risk factor. No heterogeneity was observed (p-values for the Q-statistics ranged from 0.51 to 0.87) and so the primary data from the three studies were pooled and analyzed using a fixed effects model. Any residual effect of combining data across study sites was controlled for in all models using pooled data through inclusion of study site as a covariate in multivariate analyses. We subsequently repeated these analyses using GEE (generalized estimating equations) analysis in order to account for potential clustering within study site, assuming an unstructured covariance structure, and observed similar effects to the previous analyses; thus the results of the initial analyses are reported. Additionally, all analyses controlled for household size as a potential covariate. Heterogeneity of effects was also assessed in the pooled data analyses by entering interaction terms for each risk factor by study site in the multivariate model. Again, no heterogeneity of effects was observed and the analyses were run with only main effects. To limit the impact of collinearity, correlations between covariates were examined and it was determined that no variables were correlated enough that it would affect our models. Prevalence odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals are presented. All statistical tests were 2-sided and P < .05 was considered statistically significant. Data were analyzed using SAS version 9.2 software (SAS Institute Inc., North Carolina).

RESULTS

STUDY POPULATION CHARACTERISTICS

The total study sample consisted of 296 index cases and 798 household members. The US study included 139 index cases and 467 household members, the NL study included 61 index cases and 114 household members, and the AU study included 96 index cases and 217 household members. Of the 296 index cases, 44% (n = 131) were male and 24% (n = 70) were under 18 years of age. Among those over 18 years of age (n = 226), 74% (n = 167) had completed high school. The average household size was 3.7 people (SD = 1.7).

Table 2 presents the distribution of index patient- and household-level sociodemographic characteristics, acquisition and transmission risk factors by study. Studies differed on multiple variables. For example, a relatively low proportion of index patients in the US study were born in the US. Also, a relatively low proportion of index patients had recent exposure to healthcare settings. In the NL study, a relatively large proportion of index patients and non-index household members had recent exposure to healthcare settings. In the AU study, a relatively large proportion of index patients played sports and had recently traveled internationally. Towel sharing was more common among household members in the AU study and less common in the US study. Index patient colonization with the clinical isolate was more common in the NL study and less common in the US study. In summary, the three studies included very different sample populations with regards to index patient- and household-level sociodemographic characteristics, acquisition and transmission risk factors.

Table 2.

Distribution of index patient and household sociodemographic characteristics and risk factors by study

| US N= 139 |

NL N= 61 |

AU N= 96 |

Pooled N= 296 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | P | N | % | |

| Index patient sociodemographic characteristics | |||||||||

| Male | 51 | 37 | 29 | 48 | 51 | 53 | 0.04 | 131 | 44 |

| ≤18 years | 41 | 29 | 9 | 15 | 20 | 21 | 0.06 | 70 | 24 |

| Born in country | 19* | 14 | 55* | 90 | 70* | 73 | <.001 | 144 | 49 |

| Graduated high school | 63 | 45 | 40 | 66 | 64 | 67 | 0.00 | 167 | 56 |

| Index patient acquisition risk factors | |||||||||

| In day care | 9 | 6 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 0.30 | 14 | 5 |

| In school | 42* | 30 | 6 | 10 | 9* | 9 | <.001 | 57 | 19 |

| Working | 53 | 38 | 28 | 46 | 35 | 36 | 0.47 | 116 | 39 |

| Plays sports | 36* | 26 | 28 | 46 | 52* | 54 | <.001 | 116 | 39 |

| Recent international travel | 29* | 21 | 32* | 52 | 48* | 50 | <.001 | 109 | 37 |

| Recent surgery | 16* | 12 | 33* | 54 | 17 | 18 | <.001 | 66 | 22 |

| Recent hospital admission | 31* | 22 | 34* | 56 | 37 | 39 | <.001 | 102 | 34 |

| Index patient transmission risk factors | |||||||||

| Recent skin condition | 32 | 23 | 15 | 25 | 33 | 34 | 0.14 | 80 | 27 |

| Recent abscess | 129* | 93 | 32 | 52 | 34* | 36 | <.001 | 195 | 66 |

| Index patient colonized with the clinical isolate | 21* | 15 | 37* | 61 | 23 | 24 | <.001 | 81 | 27 |

| Other HH member acquisition risk factors | |||||||||

| Recent surgery | 11 | 8 | 16* | 26 | 10 | 10 | 0.00 | 37 | 13 |

| HH transmission risk factors | |||||||||

| Pet presence (dog/cat) | 43 | 31 | 24 | 39 | 45 | 47 | 0.05 | 112 | 38 |

| Towel sharing | 37* | 27 | 20 | 33 | 83* | 86 | <.001 | 140 | 47 |

| Razor sharing | 19 | 14 | 8 | 13 | 9 | 9 | 0.57 | 36 | 12 |

| Recent skin condition | 53 | 38 | 27 | 44 | 48 | 50 | 0.19 | 128 | 43 |

| Recent abscess | 130* | 94 | 34 | 58 | 55* | 57 | <.001 | 219 | 74 |

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | P | Mean | SD | |

| HH sociodemographic characteristics | |||||||||

| Household size | 4.4 | 1.8 | 2.9 | 1.1 | 3.3 | 1.5 | <.001 | 3.7 | 1.7 |

| Percent of males (× 10) | 44.5 | 22.3 | 46.1 | 17.0 | 50.1 | 16.7 | 0.03 | 46.6 | 19.7 |

| Percent of children <18 years (×10) | 30.8 | 23.4 | 18.0 | 23.7 | 21.1 | 24.7 | <.001 | 25.0 | 24.5 |

| Time to Interview | |||||||||

| Days from clinical culture to interview | 33 | 20 | 43 | 25 | 114 | 76 | <.001 | 61 | 59 |

Notes:

P-value refers to test for heterogeneity between studies. Chi-square tests were used for categorical variables and ANOVA for continuous variables.

indicates standardized residuals are>1.96 or <-1.96, thus indicating which specific study is accounting for observed heterogeneity between studies

HH = household

MOLECULAR CHARACTERIZATION OF S. AUREUS ISOLATES

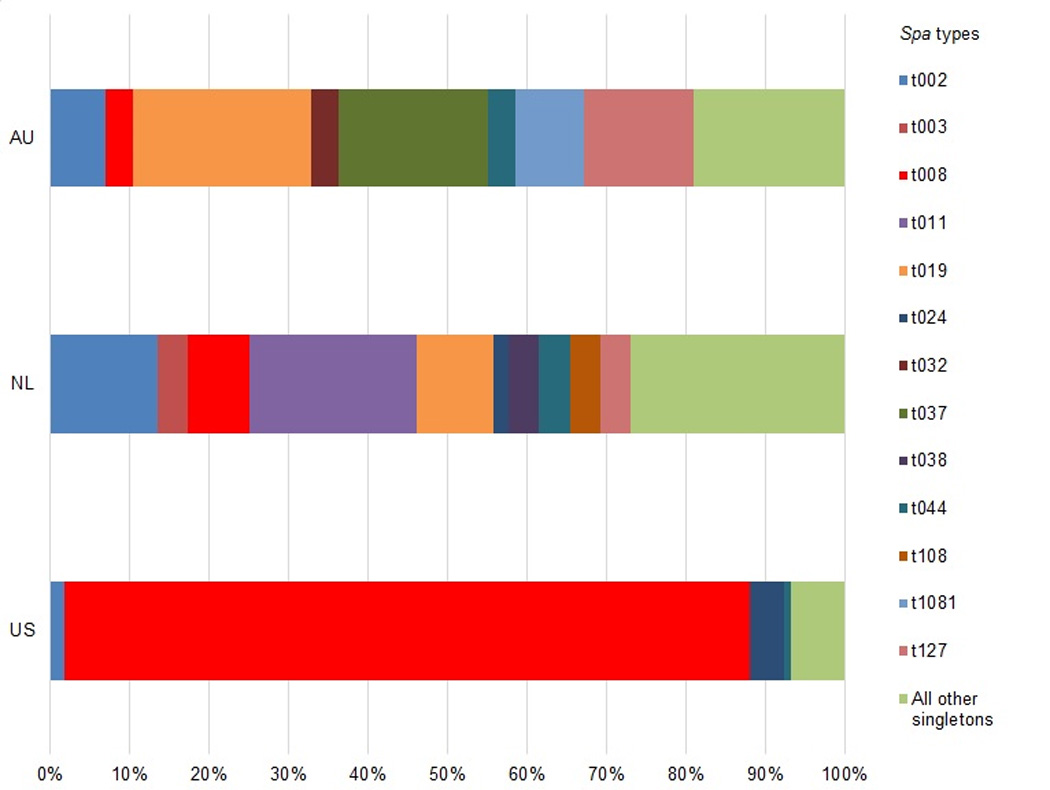

Overall, there was diversity of index patient clinical strain types between each study. Figure 1 presents the distribution of index patient spa types of clinical isolates by study. In the US study, MRSA t008 (USA300) was the predominant strain type, accounting for 73% (n=101) of index patient infections. In the NL study, there was a much wider assortment of strain types causing index patient infection, with 29 different strain types accounting for 61 infections and MRSA t008 only accounting for 7% (n=4) of index patient infections. The most commonly identified strain was MRSA t011, which accounted for 18% (N=11) of infections. In the AU study, there was not a single predominant epidemic strain. The most common strain types were MRSA t019 (13%, n = 13), MRSA t037 (11%, n = 11), and MRSA t202 (10%, n = 10). MRSA t008 only accounted for 3% (n=2) of index patient infections. A few strain types were identified across multiple studies, notably MRSA t002 (US: 1%, n=2; NL: 11%, n=7; AU: 5%, n=5), and MRSA t008 (US: 73%, n=101; NL: 7%, n=4; AU: 2%, n=2). MRSA t019 was relatively common in the NL (13%, n = 13) and AU (17%, n = 13) studies.

Figure 1.

Distribution of clinical isolate spa types by study

One fifth (20%, n=18) of the 97 index patient clinical isolates in the AU study could not be spa-typed because the specimens retrieved from the private pathology service were no longer viable. In these cases, antibiograms run by the private pathology service were used to confirm that the clinical isolates were MRSA. In one of these 18 households, a non-index household member was colonized with MRSA; however, it had a different resistance pattern than the clinical isolate and so we have excluded this as a transmission event. No other possible transmission episodes occurred in the households where the index patient isolate was not available for typing.

S. AUREUS COLONIZATION AND TRANSMISSION

Colonization patterns were different among the studies. Table 3 presents the distribution of S. aureus colonization among index patients, S. aureus colonization among non-index household members, and S. aureus transmission by study. In the NL study, the index case had a high level of colonization with MRSA (62%) compared with the other studies. Among non-index household members, the NL study had a low level (20%) of colonization with methicillin susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) compared with the other studies. Among the pooled data, sixty-seven households (23%) had evidence of transmission of the clinical isolate. Despite the different levels of colonization among the studies, levels of transmission of the clinical isolate were not different across the studies (US: 27%, n=37; NL: 21%, n=13; AU: 18%, n=17; P = .266).

Table 3.

Colonization and transmission of S. aureus by study

| US N= 139 |

NL N= 61 |

AU N= 96 |

Pooled N= 296 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | P | N | % | |

| S. aureuscolonization among index patients | |||||||||

| Colonized with S. aureus | 37* | 27 | 41* | 67 | 44 | 46 | <.001 | 122 | 41 |

| Colonized with MRSA | 22* | 16 | 38* | 62 | 25 | 26 | <.001 | 85 | 29 |

| Colonized with MSSA | 15 | 11 | 3 | 5 | 19 | 20 | 0.06 | 37 | 13 |

| S. aureuscolonization among non-index HHMs | |||||||||

| Colonized with S. aureus | 89 | 64 | 23 | 38 | 52 | 54 | <.01 | 164 | 55 |

| Colonized with MRSA | 39 | 28 | 13 | 21 | 24 | 25 | 0.59 | 76 | 26 |

| Colonized with MSSA | 63 | 45 | 12* | 20 | 39 | 41 | <.01 | 114 | 39 |

| S. aureustransmission of the clinical isolate | |||||||||

| ≥1 non-index HHM colonized with the clinical strain | 37 | 27 | 13 | 21 | 17 | 18 | 0.27 | 67 | 23 |

Notes:

P-value refers to test for heterogeneity between studies. Chi-square tests were used for categorical variables and ANOVA for continuous variables.

indicates standardized residuals are>1.96 or <-1.96, thus indicating which specific study is accounting for observed heterogeneity between studies

HHM = household member

RISK FACTORS FOR HOUSEHOLD TRANSMISSION

Bivariate analyses assessing risk factors for household transmission of the clinical isolate were conducted among each study. In the US study, the index patient being colonized with the clinical isolate at the time of the home visit was positively associated with household transmission of the clinical isolate (P = .02). In the AU study, household size was positively associated with household transmission of the clinical isolate (P = .04) [see Supplementary Table S1].

The data were pooled to assess risk factors for household transmission of S. aureus across studies and strain types. Table 4 presents the results of these analyses. In bivariate models, being born in country, the index patient being colonized with the clinical isolate at the time of the home visit, household size, and percent of children in the household were positively associated with transmission at P<.20. An increased time interval between the sampling of the clinical isolate and colonization among the household was negatively associated with transmission at P<.20. These variables were selected for multivariate analyses.

Table 4.

Bivariate analyses of index patient and HH characteristics by HH transmission of the clinical isolate among pooled data

| HH transmission N = 67 |

No HH transmission N = 229 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | POR | (95% CI) | P | |

| Index patient sociodemographic characteristics | |||||||

| Male | 27 | 40 | 104 | 45 | 0.9 | 0.6 – 1.4 | 0.65 |

| ≤18 years | 20 | 30 | 50 | 22 | 1.2 | 0.8 – 1.9 | 0.46 |

| Born in country | 32 | 48 | 112 | 49 | 1.5 | 0.9 – 2.5 | 0.15 |

| Graduated high school | 38 | 57 | 129 | 56 | 1.2 | 0.8 – 1.8 | 0.44 |

| Index patient acquisition risk factors | |||||||

| In day care | 5 | 7 | 9 | 4 | 1.4 | 0.7 – 2.8 | 0.28 |

| In school | 12 | 18 | 45 | 20 | 0.8 | 0.4 – 1.3 | 0.33 |

| Working | 23 | 34 | 93 | 41 | 0.8 | 0.5 – 1.2 | 0.30 |

| Plays sports | 27 | 40 | 89 | 39 | 1.2 | 0.7 – 1.8 | 0.50 |

| Recent international travel | 19 | 28 | 90 | 39 | 0.7 | 0.5 – 1.2 | 0.24 |

| Recent surgery | 13 | 19 | 53 | 23 | 0.9 | 0.5 – 1.6 | 0.75 |

| Recent hospital admission | 18 | 27 | 84 | 37 | 0.8 | 0.5 – 1.3 | 0.28 |

| Index patient transmission risk factors | |||||||

| Recent skin condition | 14 | 21 | 66 | 29 | 0.7 | 0.4 – 1.3 | 0.28 |

| Recent abscess | 47 | 70 | 148 | 65 | 0.9 | 0.5 – 1.7 | 0.84 |

| Index patient colonized with the clinical isolate | 26 | 39 | 55 | 24 | 2.2 | 1.4 – 3.5 | <.001 |

| Other HH member acquisition risk factors | |||||||

| Recent surgery | 9 | 13 | 28 | 12 | 1.1 | 0.6 – 2.0 | 0.82 |

| HH transmission risk factors | |||||||

| Pet presence (dog/cat) | 27 | 40 | 85 | 37 | 1.1 | 0.7 – 1.7 | 0.63 |

| Towel sharing | 32 | 48 | 108 | 47 | 1.2 | 0.8 – 1.9 | 0.34 |

| Razor sharing | 9 | 13 | 27 | 12 | 1.0 | 0.5 – 1.9 | 0.98 |

| Recent skin condition | 26 | 39 | 102 | 45 | 0.8 | 0.5 – 1.3 | 0.43 |

| Recent abscess | 54 | 82 | 165 | 72 | 1.2 | 0.7 – 2.3 | 0.51 |

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | POR | (95% CI) | P | |

| HH sociodemographic characteristics | |||||||

| Household size | 4.1 | 1.9 | 3.6 | 1.6 | 1.1 | 1.0 – 1.3 | 0.05 |

| Percent of males (× 10) | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 0.9 – 1.1 | 0.98 |

| Percent of children <18 years (×10) | 33.5 | 24.0 | 22.5 | 24.1 | 1.1 | 1.0 – 1.2 | 0.01 |

| Time to Interview | |||||||

| Days from clinical culture to interview (×10) | 49 | 42 | 65 | 63 | 1.0 | 0.9 – 1.0 | 0.07 |

POR = Prevalence odds ratio

HH = household

In multivariate analyses using pooled data, the index patient being colonized with the clinical isolate at the time of the home visit (POR 2.18 [1.37–3.48] P = .001) and the percent of household members that were children <18 years (POR = 1.13 [1.03–1.24] P = .008, for a 10% increase) were both independently associated with household transmission of the clinical isolate (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Multivariate analyses of index and HH characteristics by HH transmission of the clinical isolate among each study and pooled data

| US N= 139 |

NL N= 61 |

AU N= 96 |

POOLED N= 296 |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| POR | (95% CI) | P | POR | (95% CI) | P | POR | (95% CI) | P | POR | (95% CI) | P | |

| Index patient sociodemographic characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Born in country | 1.0 | 0.4 – 2.3 | 1.00 | 0.7 | 0.1 – 5.0 | 0.71 | 3.6 | 0.7 – 17.1 | 0.11 | 1.4 | 0.8 – 2.5 | 0.23 |

| Index patient transmission risk factors | ||||||||||||

| Index patient colonized with the clinical isolate | 1.9 | 1.0 – 3.6 | 0.04 | 3.7 | 1.0 – 14.4 | 0.06 | 2.1 | 0.8 – 5.5 | 0.14 | 2.2 | 1.4 – 3.5 | <.01 |

| HH sociodemographic characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Household size | 1.1 | 0.9 – 1.2 | 0.40 | 1.0 | 0.7 – 1.6 | 0.88 | 1.2 | 0.9 – 1.6 | 0.33 | 1.1 | 1.0 – 1.2 | 0.19 |

| Percent of children <18 years (×10) | 1.1 | 1.0 – 1.2 | 0.12 | 1.2 | 0.9 – 1.4 | 0.20 | 1.2 | 0.9 – 1.4 | 0.15 | 1.1 | 1.0 – 1.2 | <.01 |

| Time to Interview | ||||||||||||

| Days from clinical culture to interview (×10) | 0.9 | 0.7 – 1.0 | 0.12 | 1.0 | 0.8 – 1.2 | 0.99 | 1.0 | 0.9 – 1.0 | 0.10 | 0.9 | 0.9 – 1.0 | 0.05 |

POR = Prevalence odds ratio

HH = household

DISCUSSION

We examined heterogeneity of spread of CA-MRSA within households of infected cases across multiple geographic regions and attempted to identify common risk factors for household transmission. A diverse set of household characteristics, colonization patterns, and clonal lineages accounting for the burden of S. aureus infections in each study were observed. Despite this variability, frequency of household CA-MRSA transmission was similar across studies and we identified several common risk factors for transmission within the household. Nasal colonization of the index patient with the clinical isolate and the percent of children in the household were risk factors for CA-MRSA household transmission.

There was great diversity in clinical strain types across studies. The US study was dominated by the epidemic strain MRSA t008, which has emerged as the most common cause of CA-MRSA infections in North America [4]. While MRSA t008 was present in the NL and AU studies, most infections were caused by a diverse set of non-t008 clonal lineages. It has been speculated that, without adequate control to halt its spread, MRSA t008 will continue to gain ground around the world as the predominant epidemic clone [35]. Our findings suggest, however, that household transmission of the clinical isolate is equally likely to occur across study populations, regardless of the presence of an epidemic clone, which argues against using strain targeted intervention strategies [9].

Household colonization patterns also differed between studies. Specifically, the NL study had a higher proportion of index patients colonized with MRSA and a lower proportion of households with a non-index member colonized with MSSA. We can only speculate as to the reason for these differences. They may be a reflection of distinct treatment practices where patients in NL are less likely to be cleared of nasal colonization by the time of the home visit. On the other hand, higher levels of colonization among index patients compared to other household members in the NL study may emphasize the importance of initial index acquisition factors in this setting, versus subsequent spread among members of a shared household once MRSA has been introduced. Despite these differences in the epidemiology of S. aureus across studies, and the aforementioned differences in biology, overall levels of CA-MRSA household transmission did not differ between studies, and were similar to other reports in the community setting [5–8].

Our analyses indicate that certain risk factors are correlates of intra-household CA-MRSA transmission. Colonization of the index patient with the clinical isolate was a risk factor for the colonization of other household members with the identical clone. Failure to eliminate colonization in a household member could serve as a potential reservoir for ongoing household transmission, increasing the risk of recurrent colonization and infection even after antibiotic treatment [16–18]. These findings suggest that strategies to limit S. aureus transmission in the community setting should consider decontamination of infected individuals and their household contacts [36]. Alternatively, given that multiple strain types can often be found colonizing index patients and their household contacts after an initial infection, which has been observed among this study and others [28], another potential solution for interrupting S. aureus transmission and subsequent infection could be recolonization strategies focused on not inadvertently eliminating less pathogenic S. aureus strains and thus disrupting commensal flora [37]. Further research into this area is needed.

Our analyses also identified the presence of children in the household as a risk factor for S. aureus transmission. While the effect estimate for this finding was small, it was statistically significant, and indicates that the risk of transmission increases linearly with the proportion of children in the household. A higher proportion of children may represent an elevated level of physical contact among household members. In a previous study conducted among a sample of households with children who had a CA-MRSA infection, bathing the child was identified as a risk factor for the spread of the clinical isolate to the other household members [24]. The presence of young children was also identified as a risk factor for transmission of all S. aureus by the US research group in a case-control study of households with and without S. aureus infection [9]. However, neither children (5 – 18 years) nor young children (<5 years) with CA-MRSA infections were more likely to transmit the clinical strain to other household members compared with infected adults (19–65 years) in another multi-site study [28]. While our findings suggest that efforts to limit the spread of CA-MRSA should take into consideration host factors and the composition of infected cases’ households, particularly with regard to the presence of children, further research is still needed.

The time from culture to interview was not found to be an independent predictor of household transmission, although we did observe a trend (P=.054) that transmission was less likely to be identified when more time passed between the initial infection and the home visit. This near-finding is in accordance with the results of a previous a study that showed that colonization of non-index household members decreased over time, and that colonization was more likely to persist when multiple members of a household were colonized [13]. This is further supported by another study that showed that MRSA carriage can often be fleeting and that minimizing the time between infection and sampling can increase the odds of identifying a positive isolate [38]. Because of the far longer and more variable time from clinical culture to interview among the AU study versus the two other studies in our analyses (US and NL), we also ran the same staged analyses excluding the AU cases and achieved notably similar results, with only the index patient being colonized with the clinical isolate at the time of the home visit and the percent of children in the household being independent predictors of household transmission of the clinical isolate in multivariate analyses.

The results from the individual studies when compared to the findings from the pooled analyses were, overall, very similar. Effect estimates from the individual studies are almost all in the same direction and only vary in magnitude, so in effect the pooled results resemble a summary of the individual results. Of note, the pooled results are able to achieve statistical significance in many instances where the results from the individual studies do not, thus highlighting the increased statistical power achieved by pooling data from multiple studies. This may be of particular use as CA-MRSA infections remain relatively rare in non-epidemic settings [4], and thus studies often struggle to identify enough participating cases to adequately explore relevant research questions.

There are certain limitations to the current study. First, this is a retrospective, observational study that uses a proxy variable as evidence of probable household transmission. Therefore, neither the directionality nor the source of transmission may be ascertained and the shared strains among household members potentially indicate a shared exposure. Second, our analyses were limited to variables shared across all studies. There were other potential risk factors that were not assessed because they were not included in all three studies or were not measured uniformly. These include environmental contamination and poultry consumption, which were associated with S. aureus carriage in previous analyses using data from these studies [9,10,25]. Additionally, these three studies did not use uniform time periods for assessing previous risk factors (US: 6 months; NL & AU: one year) and these data were unable to be harmonized. Third, different culture techniques were used across studies. Ideally, uniform methods would be used across geographic locations to maximize comparability. Lastly, this study did not assess the impact of colonization of other body sites as the anterior nares was the only body site sampled in all three studies, even though this has emerged as a common feature of CA-MRSA carriage [28,32,39]. Underestimation of S. aureus colonization may, in turn, underestimate household transmission. Despite these limitations, our pooled analysis benefits from a large, diverse sample size resulting in strong analytic power and increased generalizability.

Our study identifies shared features of CA-MRSA household transmission despite geographic difference in strain profiles. The spread of CA-MRSA among households increases the likelihood of re-infection among its members [10,16–18]. Furthermore, the ability of infectious S. aureus strains to persist in households increases the likelihood that they will spread through the community [11–14]. Our findings suggest that decontamination strategies targeting the household unit may be effective in reducing the transmission of S. aureus colonization and infection in the community setting. Such interventions appear applicable across diverse, international patient populations. Prospective, multicenter studies are needed to further define the transmission patterns of this prevalent and highly pathogenic organism.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

FINANCIAL SUPPORT

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [grant numbers AI077690, AI090013]; the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMw); and the National Health & Medical Research Council [grant number 509304].

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.

ETHICAL STANDARDS

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Herold BC, et al. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in children with no identified predisposing risk. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;279:593–598. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.8.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grundmann H, et al. Emergence and resurgence of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus as a public-health threat. Lancet. 2006;368:874–885. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68853-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chambers HF. The changing epidemiology of Staphylococcus aureus? Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2001;7:178–182. doi: 10.3201/eid0702.010204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.David MZ, Daum RS. Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: epidemiology and clinical consequences of an emerging epidemic. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 2010;23:616–687. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00081-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wagenvoort J, et al. Transmission of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus within a household. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. 1997;16:399–400. doi: 10.1007/BF01726373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.L'Heriteau F, et al. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and familial transmission. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;282:1038–1039. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.11.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Busato CR, Carneiro Leao MT, Gabardo J. Staphylococcus aureus nasopharyngeal carriage rates and antimicrobial susceptibility patterns among health care workers and their household contacts. Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1998;2:78–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huijsdens XW, et al. Multiple cases of familial transmission of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus . Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2006;44:2994–2996. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00846-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knox J, et al. Environmental contamination as a risk factor for intra-household Staphylococcus aureus transmission. PLoS One. 2012;7:e49900. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Uhlemann AC, et al. The environment as an unrecognized reservoir for community-associated methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus USA300: a case-control study. PLoS One. 2011;6:e22407. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zafar U, et al. Prevalence of nasal colonization among patients with community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection and their household contacts. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology. 2007;28:966–969. doi: 10.1086/518965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hugo Johansson P, Gustafsson EB, Ringberg H. High prevalence of MRSA in household contacts. Scandinavian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2007;39:764–768. doi: 10.1080/00365540701302501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lautenbach E, et al. The impact of household transmission on duration of outpatient colonization with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus . Epidemiology and Infection. 2010;138:683–685. doi: 10.1017/S0950268810000099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ho PL, et al. Molecular epidemiology and household transmission of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Hong Kong. Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease. 2007;57:145–151. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fritz SA, et al. Skin infection in children colonized with community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Journal of Infection. 2009;59:394–401. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones TF, et al. Family outbreaks of invasive community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2006;42:e76–e78. doi: 10.1086/503265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang YC, et al. Nasal carriage of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in household contacts of children with community-acquired diseases in Taiwan. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 2007;26:1066–1068. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31813429e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cook HA, et al. Heterosexual transmission of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus . Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2007;44:410–413. doi: 10.1086/510681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fritz SA, et al. Household versus individual approaches to eradication of community-associated Staphylococcus aureus in children: a randomized trial. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2012;54:743–751. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller LG, et al. Prospective investigation of nasal mupirocin, hexachlorophene body wash, and systemic antibiotics for prevention of recurrent community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2012;56:1084–1086. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01608-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mollema FP, et al. Transmission of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus to household contacts. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2010;48:202–207. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01499-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lucet JC, et al. Carriage of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in home care settings: prevalence, duration, and transmission to household members. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2009;169:1372–1378. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Calfee DP, et al. Spread of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) among household contacts of individuals with nosocomially acquired MRSA. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology. 2003;24:422–426. doi: 10.1086/502225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nerby JM, et al. Risk factors for household transmission of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus . Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 2011;30:927–932. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31822256c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Rijen MM, et al. Lifestyle-associated risk factors for community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus carriage in the Netherlands: an exploratory hospital-based case-control study. PLoS One. 2013;8:e65594. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bennett CM, et al. Community-onset Staphylococcus aureus infections presenting to general practices in South-eastern Australia. Epidemiology and Infection. 2013:1–11. doi: 10.1017/S0950268813001581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shopsin B, et al. Evaluation of protein A gene polymorphic region DNA sequencing for typing of Staphylococcus aureus strains. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1999;37:3556–3563. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.11.3556-3563.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller LG, et al. Staphylococcus aureus colonization among household contacts of patients with skin infections: risk factors, strain discordance, and complex ecology. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2012;54:1523–1535. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Knol MJ, et al. Potential misinterpretation of treatment effects due to use of odds ratios and logistic regression in randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21248. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McNutt LA, et al. Estimating the relative risk in cohort studies and clinical trials of common outcomes. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2003;157:940–943. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2004;159:702–706. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller M, et al. Staphylococcus aureus in the community: colonization versus infection. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6708. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied logistic regression. New York: Wiley; 1989. p. 108. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mickey RM, Greenland S. The impact of confounder selection criteria on effect estimation. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1989;129:125–137. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tenover FC, Goering RV. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strain USA300: origin and epidemiology. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2009;64:441–446. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bocher S, et al. The search and destroy strategy prevents spread and long-term carriage of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: results from the follow-up screening of a large ST22 (E-MRSA 15) outbreak in Denmark. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2010;16:1427–1434. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.03137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iwase T, et al. Staphylococcus epidermidis Esp inhibits Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation and nasal colonization. Nature. 2010;465:346–349. doi: 10.1038/nature09074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morris DO, et al. Potential for pet animals to harbour methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus when residing with human MRSA patients. Zoonoses and Public Health. 2012;59:286–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1863-2378.2011.01448.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee CJ, et al. Staphylococcus aureus oropharyngeal carriage in a prison population. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2011;52:775–778. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.