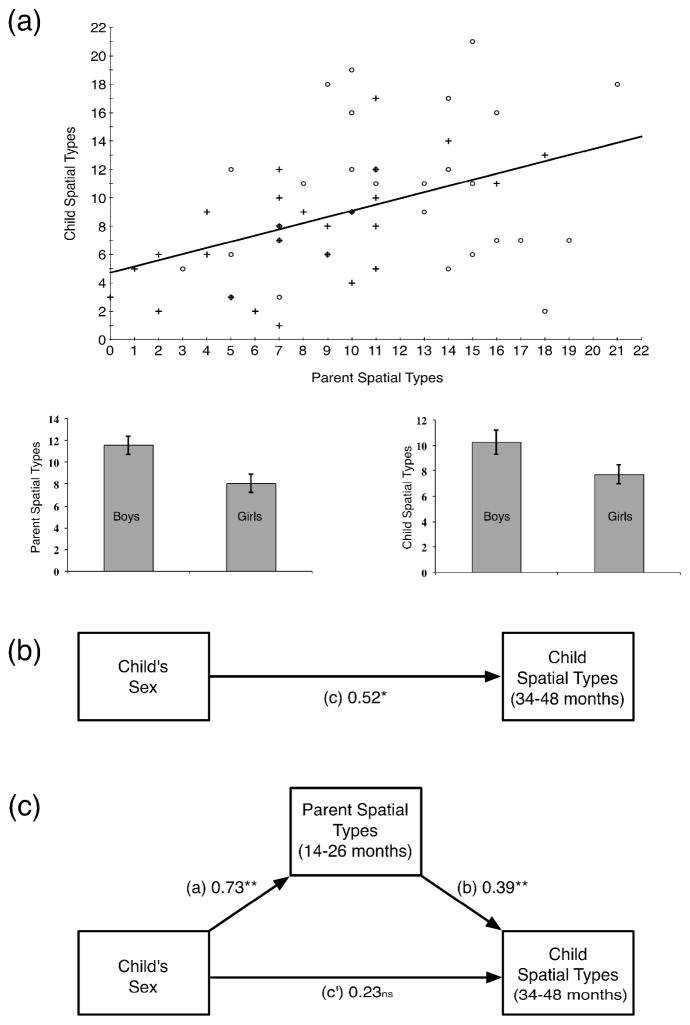

Figure 2.

Scatter plot and bar graphs (1a) showing: (1) relation between parent ‘spatial types’ between 14 and 26 months and child ‘spatial types’ between 34 and 46 months. °represent data points for boys; ✚ represent data points for girls (top graph; r = 0.44, p ≤ .001), (2) the relation between child sex and parent ‘spatial types’ by 46 months (left bar graph; r = 0.37, p ≤ .01) and (3) the relation between child sex and child ‘spatial types’ by 46 months (right bar graph; r = 0.26, p ≤ .05). Mediation analysis revealed the direct effect (c) of child sex on child ‘spatial types’ (1b) is no longer significant when parent’s ‘spatial types’ are included as a potential mediator (1c; c′). These results suggest that parent ‘spatial types’ accounts for the sex differences in children’s ‘spatial types.’ Adj. R2 = .1742 (n = 57, β = Standardized regression coefficient, *p ≤ .05, **p ≤ .01, ***p ≤ .001).