Abstract

Objective

To determine the uptake of home-based HCT in four communities of the HPTN071 (PopART) trial in Zambia among adolescents aged 15–19 years and explore factors associated with HCT uptake.

Design

The PopART for Youth (P-ART-Y) study is a 3-arm community-randomized trial in 12 communities in Zambia and 9 communities in South Africa which aims to evaluate the acceptability and uptake of a HIV prevention package, including universal HIV testing and treatment, among young people. The study is nested within the HPTN071 (PopART) trial.

Methods

Using a door-to-door approach that includes systematically re-visiting households, all adolescents enumerated were offered participation in the intervention and verbal consent was obtained. Data were analysed from October 2015 to September 2016.

Results

Among 15,456 enumerated adolescents, 11,175 (72.3%) accepted the intervention. HCT uptake was 80.6% (8,707/10,809) and was similar by sex. Adolescents that knew their HIV-positive status increased almost three-fold, from 75 to 210. Following visits from Community HIV care Providers, knowledge of HIV status increased from 27.6% (3,007/10,884) to 88.5% (9,636/10,884). HCT uptake was associated with community, age, duration since previous HIV test; other household members accepting HCT, having an HIV-positive household member, circumcision and being symptomatic for STIs.

Conclusion

Through a home-based approach of offering a combination HIV prevention package the proportion of adolescents who knew their HIV status increased from ~28% to ~89% among those that accepted the intervention. Delivering a community-level door-to-door combination HIV prevention package is acceptable to many adolescents and can be effective if done in combination with targeted testing.

Keywords: Adolescents, HIV testing, Home-based HCT, Community, Zambia

Introduction

AIDS is the leading cause of death among adolescents in sub-Sahara Africa (SSA), and the second most common cause of death among adolescents globally (4). An estimated 2.1 million adolescents aged 10–19 years are living with HIV globally (1), the majority of these in SSA, including 79,000 in Zambia (1–3). More than 250 000 adolescents aged 15–19 year-olds were newly infected with HIV in 2013, with girls accounting for two out of three of these new infections globally and eight out of ten in SSA (4). The vast majority of adolescents in Africa, including those already infected with HIV, do not know their HIV status (5, 6). In SSA only 13% of adolescent girls and 9% of adolescent boys aged 15–19 have tested for HIV and received their results in the previous 12 months (7). Without current knowledge of HIV-status the subsequent steps in the HIV treatment cascade cannot be accessed (1, 8). Whilst antiretroviral therapy (ART) has dramatically improved survival for people living with HIV (PLWH), clinical outcomes of HIV-positive adolescents fall behind adults, a consequence of poor knowledge of status and lack of access to therapy (3).

Uptake of HIV counselling and testing (HCT) among adolescents in Zambia remains low (9). According to the latest Zambia Demographic Health Survey (ZDHS 2013–14) report, sexually active female adolescents were more likely to have tested for HIV in the previous 12 months compared to their males counterparts (49.7% versus 26.9%) (9). It is often more difficult for young people to seek HCT compared to adults, partly limited by the need in Zambia for all adolescents under the age of 16 years to gain parental or guardian consent prior to testing (10). Additional barriers include fear of a positive test, stigma, association of HCT with high-risk behaviour, lack of information, perceived risk with respect to sexual exposure, poor attitudes of healthcare providers and difficulty accessing testing services (3, 9, 11–18). Such challenges result in underutilization of HCT services which subsequently leads to late diagnosis, delayed initiation of ART, poorer health outcomes and increased transmission (3, 19).

Offering home-based HCT (HB-HCT) is an important strategy for increasing HCT coverage particularly among individuals who do not use health services regularly such as adolescents (3). While community-based biomedical prevention approaches that include HCT have proven effective for the general population, these have remained as pilot projects for adolescents with limited evidence in SSA (20). Robust implementation research studies are needed to provide new knowledge to improve programming and policy for highly accessible HIV testing and care, such as community-based interventions to increase adolescent HCT (21).

The HPTN071 (PopART) trial is a 3-arm community randomized trial in 12 communities in Zambia and 9 communities in South Africa (SA) evaluating the impact of a combination HIV prevention package, including universal HIV testing and treatment (UTT), on community-level HIV incidence (12). Within this study is an adolescent sub-study called PopART for Youth (P-ART-Y) which aims to determine the impact of the community-level HIV combination prevention packages on HIV prevalence over 26 months in adolescents aged 15–19 years. It will also assess the need for specific youth-targeted interventions in the context of community-wide UTT.

We report results and explore factors associated with HCT uptake by adolescents aged 15–19 years in four Arm A communities in Zambia who are offered a “full” combination HIV prevention package that includes UTT through a door-to-door approach from the P-ART-Y study. These are initial results from Arm A communities only after the first 11 months of study commencement. We acknowledge that this is early data. However, there is a strong case to be made to share lessons in real time to inform policy makers and funders timely reporting of outcomes relevant to national and global delivery of testing and care.

Methods

Trial design and setting

HPTN071 (PopART)

The main trial is a cluster randomised trial being implemented in 21 high HIV prevalent communities in Zambia and SA (22). The 21 communities were divided into 7 triplets. Each triplet was defined as a set of 3 communities with similarities in geography, size and estimated baseline HIV prevalence. Each community in a triplet was then randomly assigned to one of 3 Arms; Arm A receiving the full PopART intervention including HCT and universal ART for all HIV-positives, Arm B receiving the full PopART intervention with ART provided according to national guidelines, and Arm C being the control arm. Further details of the trial are described elsewhere (22).

The P-ART-Y study is nested within the main HPTN 071 (PopART) trial; it is being implemented in 12 communities in Zambia and 9 communities in the Western Cape Province of SA (22, 23). A community is defined as the catchment population of a local health unit (through which the intervention is delivered), including all schools in the selected area. The P-ART-Y study has three phases: qualitative baseline studies and collection of process data from the ongoing HPTN071/PopART trial (Phase 1); addition of youth-targeted interventions in communities (Phase 2); and an epidemiological survey to determine the effect of the intervention on the knowledge of HIV status (Phase 3).

We report on the adolescent population aged 15–19 years from the four Arm A communities in Zambia using Phase 1 data.

The PopART Intervention

The PopART combination HIV prevention package is delivered by trained community health workers called CHiPs (Community HIV care providers) via a door-to-door approach, with treatment and care related services provided by local government clinics (22). The intervention is offered in the four Arm A communities and is delivered in annual rounds. CHiPs teams enumerate (list) all household members in the community including those absent, irrespective of age. They offer HCT, support for linkage to care of all identified HIV-positive individuals, ART adherence support, referral of HIV-negative men for voluntary medical male circumcision (VMMC), as well as TB and STI screening. CHiPs work in pairs within an allocated zone (consisting of 450–500 households) of a community and throughout the period, arrange repeat household visits to monitor linkage to services and offer HCT for those absent at previous visits.

CHIPs are selected by a formal process from a cadre of existing community health workers/volunteers which involves the communities. They are selected based on availability, residence in community, gender balance (58% female) and age (median age 37 years). They receive continuous training by experienced facilitators in counselling, participatory facilitation, mentoring and follow-up, and are supported by supervisory staff who routinely visit households to check their performance.

Informed consent

To participate in the PopART intervention, all household members aged 18 year and older are asked for verbal informed consent, while those younger than 18 are asked for their assent and their parents’ consent. Consent to participate does not necessarily include consent to HCT, although this is encouraged. For HCT, according to national guidelines, those 16 years and older are asked for written consent, and those under 16 years for their parent’s written consent.

Individual written consent for other interventions such as VMMC is obtained using standard procedures as these are considered part of the routine delivery of HIV prevention services and not specifically study related.

HIV counselling and testing

HCT is offered to all household members, those who agree have the option to receive HCT as couples, a household group or individually. HIV testing is conducted according to the Zambian national algorithm that uses Alere Determine HIV-1/2 test (Alere International Limited, Japan) as a screening test and the Unigold HIV test (Trinity Biotech Manufacturing Ltd, Bray, Ireland) as the confirmatory test for individuals who have a reactive result on the screening test. Individuals with discordant screening and confirmatory tests have repeat tests immediately and repeated after two weeks if results are still discordant.

Data collection and analysis

In the main trial, the intervention has been offered to all household members 18 years and older since December 2013. Data is recorded in an electronic data capture device (EDC). Collection of additional data on the uptake of the intervention for those under 18 years began in October 2015 following ethical approvals. We report on data collected from October 2015 to September 2016 for adolescents aged 15–19 years from four Arm A communities in Zambia. Arm A communities only were included in this analysis as they all received the same combination prevention package and no comparisons with standard of care communities was done.

Univariable and multivariable random-effects logistic regression was used to estimate unadjusted odds ratio (OR) and adjusted (aOR), with all analysis controlled for community. Analysis was done separately for males and females, with zone as a random effect to account for clustering due to variation in CHiPs’ performance. Association between HCT uptake and variables that include age, sex, community, time since previous HIV test and presence of young or older adults in the household was explored. The likelihood ratio test was used to compare the fit of different models and quantify evidence of associations between individual characteristics and HCT uptake. In multivariable models, age group and prior history of HCT were considered for inclusion first, and confounding among community, age group, and previous history of HCT was explored. Following this, other factors were considered and those found to be association with the outcome (p<0.10) in multivariable analysis were included. Analysis was restricted to individuals with complete data.

Knowledge of HIV status before the intervention was defined as self-reported HIV-positive or self-report to have tested HIV-negative in the previous 12 months. Knowledge of HIV status after intervention was defined as self-reported HIV positive, tested by CHiPs or tested HIV negative elsewhere in the previous 12 months. Comparison of knowledge of HIV status by age and sex was done since these are widely acknowledged risk factors (24).

To calculate HIV-prevalence, we assumed that all adolescents who knew their HIV positive status self-reported this to the CHiPs and that the proportion of HIV-positives in those not accepting testing was the same as those accepting testing. HIV-prevalence was defined as the sum of self-reported HIV positive, tested positive by CHiPs and those estimated to be HIV positive among those declining testing, divided by the number of adolescents consenting.

To calculate the UNAIDS ‘first 90’ among consenters and the population we assumed that (a) all consenting adolescents who knew HIV positive status, self-reported this to the CHiPs (b) proportion of HIV-positives who knew their status was similar in those not consenting as in those consenting (at time of CHiPs visit) (c) the proportion of those testing HIV-positive among those accepting testing by CHiPs was the same in those consenting to the intervention but declining testing and those estimated to be eligible for HIV testing in the group not consenting to the intervention. The ‘first 90 before the intervention’ defines those who knew their HIV-positive status among those estimated to be HIV positive before the CHiPs’ visit. The ‘first 90 after the intervention’ defines the same but immediately after the CHiPs’ visit and includes the impact of HCT.

Ethical approval

Ethics approval was obtained from the ethics committees of the University of Zambia and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. Permission to conduct the study was received from the Ministry of Health.

Results

Participation

From June 2015 to September 2016, 97.6% (45,631/46,762) of the total households were visited by CHiPs (figure 1). Enumeration of households was completed for 94.2% (43,008/45,631) and average household size was 4.7 individuals (201,826 members in 43,008 households).

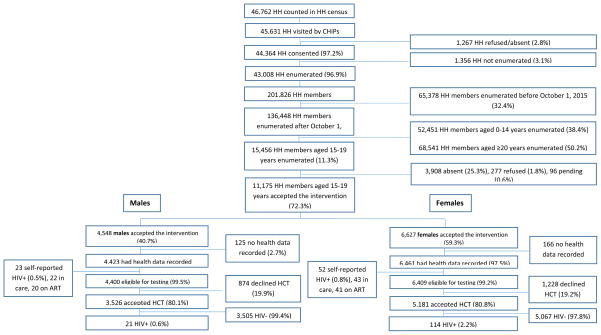

Figure 1.

Flow chart showing study intervention participation and HIV-testing eligibility

15,456 adolescents aged 15–19 were enumerated and 277 (1.8%) refused to participate in the intervention. Refusal was highest among the 18 year olds (95/3,450; 2.8%). Refusal was higher in males than females (150/6,957; 2.2% versus 127/8,499; 1.5%). CHiPs were not able to contact 3,908/15,456 (25.3%) adolescents. For males 31.9% (2,219/6,957) could not be contacted and for females 19.9% (1,689/8,499). 15-year olds adolescents were more difficult to contact (1,036/2,786; 37.2%) than older ages.

A total of 72.3% (11,175/15,456) adolescents accepted the intervention (40.7% (4,548/11,175) males; 59.3% (6,627/11,175) females). For 10,884/11,175 (97.4%) adolescents, health data was electronically recorded after accepting the intervention. In total 75/10,884 (0.7%) adolescents self-reported to be HIV-positive; leaving 10,809 adolescents eligible for HIV-testing (figure 1). Of the self-reported HIV-positives, more males than females were linked to care (22/23 males, 95.6%; 43/52 females, 82.7%). Most adolescents were on ART (20/22 males, 90.9%; 41/43 females, 95.3%).

HCT Uptake

Overall 80.6% (8,707/10,809) adolescents accepted HIV-testing by the CHiPs. HCT uptake was similar by sex (80.8% females; 80.1% males) (figure 1). Main reasons for refusing testing varied per age. Among younger age groups the main reason for refusal was ‘not considered at risk’ (37% in 15 year old males; 32% in 15 year old females) while among older adolescents ‘recently tested’ was the main reason for refusal (35% in 19 year old males; 44% in 19 year old females). On average about 19% of decliners gave ‘other’ reasons for refusing to be tested, 15% were ‘too busy’, 11% did not give a reason and some feared the result of the test (1.5%) or the finger prick (1.5%) (Data not shown).

Over half of the adolescents had never been tested for HIV before (60.6% (2,665/4,400) males and 53.1% (3,406/6,409) females). There was a trend between age and potential first time testers whereby younger adolescents were less likely to have tested before compared to older ones (79.8% (1,304/1,634) never tested in 15 year olds and 30.3% (846/2,790) in 19 year olds).

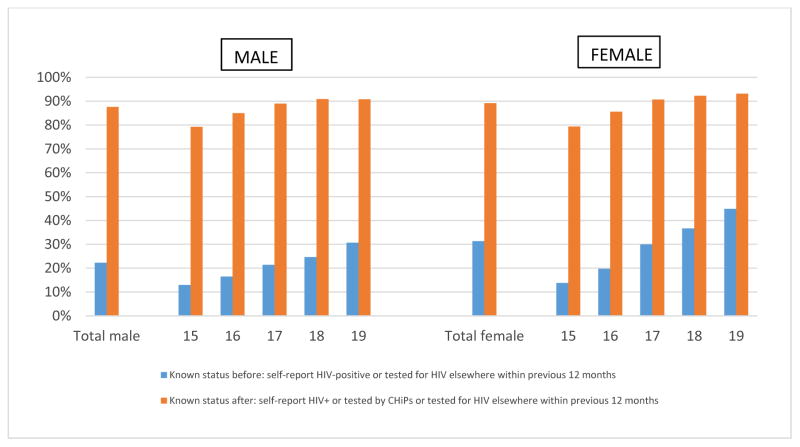

Of consenting adolescents, 27.6% (3,007/10,884) knew their HIV status before the intervention and 88.6% (9,636/10,884) after the intervention. For males the increase was from 22.3% (986/4,423) to 87.6% (3,876/4,423); for females from 31.3% (2,021/6,461) to 89.1% (5,760/6,461) (figure 2). The highest impact of the intervention in terms of knowing one’s HIV-status was among 16 year old males (16.5% before to 85.0% after the intervention) and 16 year old females (19.7% before to 85.6% after the intervention).

Figure 2.

Knowledge of HIV-status before and after the intervention by age and sex

Factors associated with HCT uptake

In univariable analysis, factors associated with HCT uptake were community, age, time since previous HIV test, having at least one adult in the household previously tested by CHiPs, and being symptomatic for STIs (table 1). Additionally, for males, circumcision was associated with HCT uptake while for females, having a known HIV-positive young adult (aged 20–34) in the household was associated with HCT uptake. These associations were maintained in the multivariable analysis, with the exception of STI symptoms among males.

Table 1.

Factors associated with uptake of home-based HCT by sex

| MALES | Univariate1 | Multivariate | FEMALES | Univariate1 | Multivariate | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | N | Accept HIV test | % | N | Accept HIV test | % | ||||||||||||

| OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p | |||||||

| Total | 4,400 | 3,526 | 80.1 | 6,409 | 5,181 | 80.8 | ||||||||||||

| Community | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||||

| Z2 | 583 | 471 | 80.8 | 1.15 | 0.65–2.02 | 0.87 | 0.49–1.57 | 850 | 688 | 80.9 | 1.06 | 0.63–1.78 | 0.92 | 0.54–1.58 | ||||

| Z5 | 1,207 | 1,097 | 90.9 | 3.74 | 2.34–6.01 | 2.90 | 1.77–4.75 | 1,717 | 1,559 | 90.8 | 3.19 | 2.08–2.89 | 2.80 | 1.81–4.34 | ||||

| Z8 | 1,982 | 1,506 | 76.0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 2,899 | 2,239 | 77.2 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| Z10 | 628 | 452 | 72.0 | 0.77 | 0.49–1.21 | 0.73 | 0.45–1.18 | 943 | 695 | 73.7 | 0.75 | 0.49–1.14 | 0.87 | 0.57–1.35 | ||||

| Age | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||||

| 15 | 681 | 504 | 74.0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 944 | 696 | 73.7 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 16 | 829 | 643 | 77.6 | 1.27 | 0.98–1.64 | 1.42 | 1.08–1.87 | 1,197 | 962 | 80.4 | 1.52 | 1.23–1.89 | 1.69 | 1.35–2.13 | ||||

| 17 | 745 | 610 | 81.9 | 1.74 | 1.33–2.29 | 2.03 | 1.51–2.72 | 997 | 816 | 81.8 | 1.80 | 1.43–2.27 | 2.27 | 1.77–2.90 | ||||

| 18 | 1,049 | 867 | 82.7 | 1.73 | 1.35–2.23 | 2.27 | 1.72–3.00 | 1,610 | 1,346 | 83.6 | 1.87 | 1.52–2.30 | 2.53 | 2.02–3.18 | ||||

| 19 | 1,096 | 902 | 82.3 | 1.68 | 1.31–2.16 | 2.22 | 1.68–2.94 | 1,661 | 1,361 | 81.9 | 1.63 | 1.33–2.00 | 2.41 | 1.91–3.05 | ||||

| Previous HIV test | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||||

| Not tested | 2,665 | 2,235 | 83.9 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 3,406 | 2,846 | 83.6 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 0–3 months (recently tested) | 326 | 135 | 41.4 | 0.15 | 0.11–0.19 | 0.11 | 0.08–0.15 | 746 | 404 | 54.2 | 0.24 | 0.20–0.30 | 0.20 | 0.17–0.25 | ||||

| 4–6 months | 278 | 209 | 75.2 | 0.63 | 0.46–0.87 | 0.52 | 0.37–0.72 | 513 | 431 | 84.0 | 1.12 | 0.86–1.47 | 0.90 | 0.68–1.19 | ||||

| 7–9 months | 187 | 152 | 81.3 | 1.00 | 0.67–1.51 | 0.71 | 0.46–1.08 | 384 | 328 | 85.4 | 1.17 | 0.85–1.60 | 0.96 | 0.69–1.33 | ||||

| 10–12 months | 178 | 144 | 80.9 | 0.98 | 0.64–1.50 | 0.68 | 0.44–1.06 | 340 | 286 | 84.1 | 1.21 | 0.88–1.67 | 0.97 | 0.69–1.35 | ||||

| >= 12 months | 735 | 627 | 85.3 | 1.15 | 0.60–1.46 | 0.90 | 0.69–1.18 | 1,001 | 869 | 86.8 | 1.30 | 1.05–1.62 | 1.02 | 0.81–1.29 | ||||

| Unknown | 31 | 24 | 77.4 | 0.58 | 0.23–1.46 | 0.51 | 0.19–1.38 | 19 | 17 | 89.5 | 1.37 | 0.29–6.40 | 1.21 | 0.25–5.81 | ||||

| Young adults 20–34 in HH ever tested by CHiPs | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||||

| No young adult tested | 2,048 | 1,547 | 75.5 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 3,126 | 2,393 | 76.6 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 1 young adult tested | 1,470 | 1,211 | 82.4 | 1.52 | 1.27–1.82 | 1.61 | 1.33–1.96 | 2,170 | 1,810 | 83.4 | 1.48 | 1.27–1.72 | 1.53 | 1.31–1.79 | ||||

| 2 young adults tested | 562 | 486 | 86.5 | 1.98 | 1.50–2.61 | 1.95 | 1.46–2.62 | 751 | 664 | 88.4 | 2.30 | 1.79–2.95 | 2.26 | 1.74–2.94 | ||||

| 3 or more young adults tested | 320 | 282 | 88.1 | 2.26 | 1.56–3.28 | 2.16 | 1.46–3.20 | 362 | 314 | 86.7 | 1.83 | 1.31–2.54 | 1.59 | 1.13–2.25 | ||||

| Older adults => 35 in HH ever tested by CHiPs | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.001 | ||||||||||||||

| No older adult tested | 2,197 | 1,700 | 77.4 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 3,727 | 2,933 | 78.7 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 1 older adult tested | 1,459 | 1,204 | 82.5 | 1.32 | 1.10–1.59 | 1.31 | 1.08–1.59 | 1,813 | 1,513 | 83.5 | 1.34 | 1.14–1.56 | 1.36 | 1.15–1.60 | ||||

| 2 or more older adults tested | 744 | 622 | 83.6 | 1.37 | 1.08–1.74 | 1.43 | 1.10–1.84 | 869 | 735 | 84.6 | 1.39 | 1.12–1.73 | 1.42 | 1.13–1.78 | ||||

| Known HIV-positive young adults 20–34 in HH | 0.195 | 0.001 | 0.007 | |||||||||||||||

| No | 4,079 | 3,258 | 79.9 | 1.00 | 5,911 | 4,750 | 80.4 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Yes | 321 | 268 | 83.5 | 1.24 | 0.89–1.72 | 498 | 431 | 86.5 | 1.56 | 1.18–2.06 | 1.50 | 1.11–2.03 | ||||||

| Known HIV-positive older adults => 35 in HH | 0.712 | 0.064 | 0.004 | |||||||||||||||

| No | 3,954 | 3,154 | 79.8 | 1.00 | 5,806 | 4,685 | 80.7 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 1 older adult HIV-positive | 404 | 312 | 77.2 | 0.89 | 0.69–1.17 | 493 | 411 | 83.4 | 1.35 | 1.04–1.75 | 1.60 | 1.21–2.12 | ||||||

| 2 or more older adults HIV-positive | 81 | 60 | 74.1 | 0.96 | 0.55–1.68 | 110 | 85 | 77.3 | 0.98 | 0.60–1.58 | 1.09 | 0.66–1.82 | ||||||

| TB | 0.189 | 0.290 | ||||||||||||||||

| Not symptomatic | 4,385 | 3,513 | 80.1 | 1.00 | 6,379 | 5,154 | 80.8 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| On treatment | 1 | 1 | 100.0 | 5 | 4 | 80.0 | 1.03 | 0.11–9.96 | ||||||||||

| TB suspects | 14 | 12 | 85.7 | 2.67 | 0.54–13.09 | 25 | 23 | 92.0 | 2.83 | 0.65–12.43 | ||||||||

| Pregnant | 0.269 | |||||||||||||||||

| No | 6,001 | 4,853 | 80.9 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||

| Yes | 371 | 300 | 80.9 | 0.85 | 0.64–1.13 | |||||||||||||

| Missing | 37 | 28 | 75.7 | |||||||||||||||

| STI | 0.034 | <0.001 | 0.003 | |||||||||||||||

| Not symptomatic | 4,363 | 3,494 | 80.1 | 1.00 | 6,329 | 5,113 | 80.8 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Symptomatic | 21 | 20 | 95.2 | 5.62 | 0.73–43.30 | 59 | 56 | 94.9 | 4.97 | 1.52–16.25 | 4.62 | 1.38–15.50 | ||||||

| Missing | 16 | 12 | 75.0 | 21 | 12 | 57.1 | ||||||||||||

| Circumcision | 0.025 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||||||

| Not circumcised | 2,405 | 1,929 | 80.2 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||||||

| VMMC | 1,738 | 1,405 | 80.8 | 1.15 | 0.96–1.37 | 1.38 | 1.15–1.68 | |||||||||||

| Traditional | 138 | 105 | 76.1 | 0.64 | 0.41–0.99 | 0.68 | 0.42–1.10 | |||||||||||

| Missing | 119 | 87 | 73.1 | |||||||||||||||

Note: Grey-shaded area variables: Co-variants not associated with outcome (HB-HCT uptake) in multivariable analysis hence results not shown

Older adolescents aged 17–19 had more than 2-fold higher odds of accepting HCT than 15 year olds. Also 16-year olds were more likely to accept HCT than 15 year olds but the effect was less pronounced (aOR: 1.42, 95% CI 1.08–1.87 males; 1.69, 95% CI 1.35–2.13 females).

There was no difference observed in HCT uptake in communities Z2, Z10 and Z8. In community Z5, adolescents had 3-fold higher odds of accepting HCT, compared with community Z8 (aOR: 2.90, 95% CI: 1.77–4.75 males; 2.80, 95% CI 1.81–4.34 females). Adolescents recently tested for HIV had the lowest odds of HCT uptake compared to those who never tested (aOR: 0.11, 95% CI 0.08–0.15 males; 0.20, 95% CI 0.17–0.25 females).

Adolescents living in households with additional one or more young (aged 20–34 years) or older (aged ≥ 35 years) adult previously tested by CHiPs had higher odds of accepting HCT compared to households with no household member previously tested by CHiPs (table 1). Additionally, in females, having an HIV-positive household member (young or older adult) in the same household was associated with higher HCT uptake (aOR: 1.60, 95% CI 1.21–2.12).

There was weak evidence that HCT uptake was associated with being symptomatic for STI (OR: 5.62, 95% CI 0.73–43.30 in males and 4.97, 95% CI 1.52–16.25 in females) and TB (OR: 2.67, 95% CI 0.54–13.09 in males and 2.83, 95% CI 0.65–12.43 in females) in univariable analysis. However, there was moderate evidence for an association for STI symptomatic females in multivariable analysis (aOR 4.62, 95% CI 1.38–15.50). VMMC was associated with slightly higher HCT uptake (aOR: 1.38, 95% CI 1.15–1.68) while traditional circumcision was weakly associated with lower HCT uptake (aOR: 0.68; 95%CI: 0.42–1.10), compared to no circumcision.

Proportion of HIV-positives among those who consented

Self-reported HIV-positives

Overall 0.5% (23/4,423) of males and 0.8% (52/6,461) of females self-reported to be HIV-positive, varying by community and age (table 2a and 2b). Female adolescents self-reporting to be HIV-positive increased with age, while this was less pronounced in males. Most adolescents who self-reported to be HIV-positive stated to have been last tested more than 12 months ago (23/23 males and 33/52 females).

Table 2a.

Self-reported HIV-positive and newly HIV-positive identified by CHiPs in adolescent males

| Characteristic | Total consented to intervention | Self-reported HIV+ | Tested HIV+ | Known HIV+ after the intervention | Proportion of HIV+ diagnosed by CHiPs | HIV-prevalence among consenters |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 4423 | 23 | 21 | 44 | 47.7% | 1.1% |

| Community | ||||||

| Z2 | 588 | 5 | 4 | 9 | 44.4% | 1.7% |

| Z5 | 1207 | 0 | 7 | 7 | 100.0% | 0.6% |

| Z8 | 1994 | 12 | 8 | 20 | 40.0% | 1.1% |

| Z10 | 634 | 6 | 2 | 8 | 25.0% | 1.4% |

| Age | ||||||

| 15 | 685 | 4 | 6 | 10 | 60.0% | 1.8% |

| 16 | 831 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 33.3% | 0.4% |

| 17 | 751 | 6 | 3 | 9 | 33.3% | 1.3% |

| 18 | 1053 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 50.0% | 0.8% |

| 19 | 1103 | 7 | 7 | 14 | 50.0% | 1.4% |

| Previous HIV test | ||||||

| Not tested | 2816 | 0 | 17 | 17 | 100.0% | 0.7% |

| 0–3 months | 326 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0% | |

| 4–6 months | 274 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 100.0% | 1.0% |

| 7–9 months | 181 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0% | |

| 10–12 months | 162 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 100.0% | 0.8% |

| >= 12 months | 635 | 23 | 1 | 24 | 4.2% | 3.8% |

| Unknown | 29 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0% | |

| Young adults 20–34 in HH ever tested by CHiPs | ||||||

| No young adult tested | 2062 | 14 | 9 | 23 | 39.1% | 1.3% |

| 1 young adult tested | 1477 | 7 | 7 | 14 | 50.0% | 1.0% |

| 2 young adults tested | 564 | 2 | 5 | 7 | 71.4% | 1.4% |

| 3 or more young adults tested | 320 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0% | |

| Older adults => 35 in HH ever tested by CHiPs | ||||||

| No older adult tested | 2212 | 15 | 13 | 28 | 46.4% | 1.4% |

| 1 older adult tested | 1466 | 7 | 8 | 15 | 53.3% | 1.1% |

| 2 or more older adults tested | 745 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.0% | 0.1% |

| Known HIV-positive young adults 20–34 in HH | ||||||

| No | 4100 | 21 | 20 | 41 | 48.8% | 1.1% |

| Yes | 323 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 33.3% | 1.0% |

| Known HIV-positive older adults => 35 in HH | ||||||

| No | 3926 | 11 | 18 | 29 | 62.1% | 0.9% |

| 1 older adult HIV-positive | 412 | 8 | 3 | 11 | 27.3% | 2.9% |

| 2 or more older adults HIV-positives | 85 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0.0% | 4.7% |

| TB | ||||||

| Not symptomatic | 4405 | 20 | 18 | 38 | 47.4% | 1.0% |

| On treatment | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0% | |

| TB suspects | 17 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 50.0% | 38.2% |

| STI | ||||||

| Not symptomatic | 4385 | 22 | 21 | 43 | 48.8% | 1.1% |

| Symptomatic | 22 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.0% | 4.5% |

| Missing | 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0% | |

| Circumcision | ||||||

| Not circumcised | 2425 | 20 | 16 | 36 | 44.4% | 1.6% |

| VMMC | 1741 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 40.0% | 0.3% |

| Traditional | 138 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 100.0% | 1.9% |

| Missing | 119 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 100.0% | 1.1% |

Table 2b.

Self-reported HIV-positive and newly HIV-positive identified by CHiPs in adolescent females

| Characteristic | Total consented to intervention | Self-reported HIV+ | Tested HIV+ | Known HIV+ after the intervention | Proportion of HIV+ diagnosed by CHiPs | HIV-prevalence among consenters 1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 6461 | 52 | 114 | 166 | 68.7% | 3.0% |

| Community | ||||||

| Z2 | 855 | 5 | 14 | 19 | 73.7% | 2.6% |

| Z5 | 1729 | 12 | 29 | 41 | 70.7% | 2.5% |

| Z8 | 2924 | 25 | 57 | 82 | 69.5% | 3.4% |

| Z10 | 953 | 10 | 14 | 24 | 58.3% | 3.0% |

| Age | ||||||

| 15 | 949 | 5 | 3 | 8 | 37.5% | 1.0% |

| 16 | 1204 | 7 | 15 | 22 | 68.2% | 2.1% |

| 17 | 1001 | 4 | 18 | 22 | 81.8% | 2.6% |

| 18 | 1620 | 10 | 43 | 53 | 81.1% | 3.8% |

| 19 | 1687 | 26 | 35 | 61 | 57.4% | 4.1% |

| Previous HIV test | ||||||

| Not tested | 3565 | 4 | 55 | 59 | 93.2% | 2.0% |

| 0–3 months | 754 | 8 | 4 | 12 | 33.3% | 2.0% |

| 4–6 months | 505 | 1 | 12 | 13 | 92.3% | 3.0% |

| 7–9 months | 377 | 5 | 5 | 10 | 50.0% | 2.9% |

| 10–12 months | 315 | 1 | 9 | 10 | 90.0% | 3.7% |

| >= 12 months | 926 | 33 | 29 | 62 | 46.8% | 7.2% |

| Unknown | 19 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0% | |

| Missing | ||||||

| Young adults 20–34 in HH ever tested by CHiPs | ||||||

| No young adult tested | 3156 | 30 | 56 | 86 | 65.1% | 3.3% |

| 1 young adult tested | 2186 | 16 | 41 | 57 | 71.9% | 3.0% |

| 2 young adults tested | 754 | 3 | 13 | 16 | 81.3% | 2.3% |

| 3 or more young adults tested | 365 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 57.1% | 2.1% |

| Older adults => 35 in HH ever tested by CHiPs | ||||||

| No older adult tested | 3759 | 32 | 73 | 105 | 69.5% | 3.3% |

| 1 older adult tested | 1826 | 13 | 26 | 39 | 66.7% | 2.4% |

| 2 or more older adults tested | 876 | 7 | 15 | 22 | 68.2% | 2.8% |

| Known HIV-positive young adults 20–34 in HH | ||||||

| No | 5949 | 38 | 100 | 138 | 72.5% | 2.7% |

| Yes | 512 | 14 | 14 | 28 | 50.0% | 5.9% |

| Known HIV-positive older adults => 35 in HH | ||||||

| No | 5846 | 40 | 99 | 139 | 71.2% | 2.8% |

| 1 older adult HIV-positive | 501 | 8 | 12 | 20 | 60.0% | 4.5% |

| 2 or more older adults HIV-positive | 114 | 4 | 3 | 7 | 42.9% | 6.9% |

| TB | ||||||

| Not symptomatic | 6427 | 48 | 107 | 155 | 69.0% | 2.8% |

| On treatment | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0% | |

| TB suspects | 29 | 4 | 7 | 11 | 63.6% | 40.0% |

| Pregnant | ||||||

| No | 6049 | 48 | 96 | 144 | 66.7% | 2.8% |

| Yes | 375 | 4 | 16 | 20 | 80.0% | 6.3% |

| Missing | 37 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 100.0% | 7.1% |

| STI | ||||||

| Not symptomatic | 6379 | 50 | 103 | 153 | 67.3% | 2.8% |

| Symptomatic | 61 | 2 | 11 | 13 | 84.6% | 22.3% |

| Missing | 21 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0% |

Newly diagnosed HIV-Positives

Of all adolescents aware of their HIV-positive status after the intervention, 47.7% (21/44) of males and 68.7% (114/166) of females were diagnosed by CHiPs. The biggest attribution was made in females aged 17 and 18 years where over 80% of the known HIV-positives were diagnosed by CHiPs (tables 2a and 2b). The number of adolescents known to have HIV increased from 75 (23 males; 52 females) to 210 (44 males; 166 females) (tables 2a and 2b). The relative benefit for the intervention varied between communities

HIV-prevalence

Overall HIV-prevalence among consenters was higher in females than males (3.0% compared to 1.1%). Expectedly, the highest prevalence was found in those with symptoms suggestive of TB and STI symptoms for females.

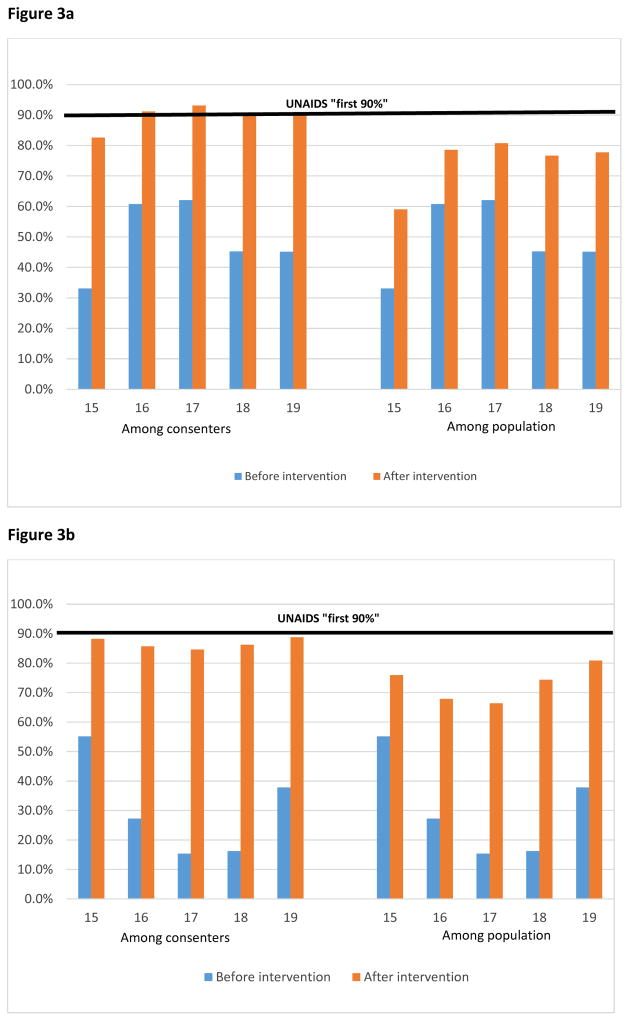

‘First 90’

All HIV-positive male adolescents’ consenters reached the ‘first 90’ after the intervention except for the 15 year olds while in females proportions were approaching the first 90 across all ages. The ‘first 90’ in the population was not equally reached in both sexes (figures 3a and 3b).

Figure 3.

Figure 3a: Proportion of HIV-positive adolescent males that know their status (first 90)

Figure 3b: Proportion of HIV-positive adolescent females that know their status (first 90)

Discussion

Uptake of home-based HCT

This study has shown that after almost one year of delivering a HB-HCT approach, the proportion of 15–19 year old adolescents who know their HIV status tripled from 27.6% to 88.6%, approaching the target goal of 90%. To our knowledge, this study is the first community based population intervention of this size that demonstrates the feasibility of delivering HB-HCT for adolescents aged 15–19 years in SSA. We show that in a high HIV-prevalence generalised epidemic, HB-HCT is acceptable and feasible for adolescents and has made a significant impact towards the first of UNAIDS 90-90-90 targets (1).

Our findings are consistent with prior research that shows that high uptake of HCT amongst adolescents can be achieved through home-base interventions (24). In Uganda, home-based family-centred HCT resulted in a six times increase of HCT uptake among individuals aged 6 to 14 years compared to that provided at clinics (24, 25). Not only do home-based approaches achieve high HCT uptake among adolescents, they also identify individuals at early stage of their HIV infection, as they do not rely on individuals presenting to health facilities with symptoms (24).

We were not able to reach 27.7% of the enumerated adolescents mostly due to absent rates especially among males and younger age groups. For such harder-to-access groups, HB-HCT can be implemented alongside other methods that have been demonstrated to increase testing rates, including provider initiated testing and counselling (PITC)(26), adolescent-friendly healthcare facilities (21), social marketing campaigns (27), mobile testing (28) as well as self-testing (29). A systematic review investigating acceptability of HCT in individuals aged 5–19 years in SSA found that PITC achieved the highest acceptability (86%), followed by HB-HCT (84.9%) but rates were lower for school-linked HCT (60.4%) and family-centred approaches (51.7%)(24).

Although HCT uptake was similar by sex, HIV prevalence was higher in females compared to males, as observed elsewhere (10, 30–32). Adolescent girls have earlier sexual debut than boys due to factors such as intergenerational sex (31), gender-based violence, economic dependency and low ability to negotiate condom use (33, 34). This has implications for future interventions which need to prioritize adolescent girls.

Factors associated with uptake of HB-HCT

Several factors at individual, household and community levels have been associated with HCT uptake (39). While these are widely acknowledged in adults, evidence is limited for adolescents. We found that HCT uptake was associated with age, community, duration since previous HIV test, having young adults in the household previously tested by CHiPs, being symptomatic for STIs, VMMC and having a known HIV-positive adult in the household.

Increasing age corresponded with increasing HCT uptake partly due to 15–17 years olds being less regularly found at home compared to 18–19 years old due to school attendance (9). This raises the potential role of testing these young adolescents through other sources. Further, the refusal rate among 15 year olds was particularly high. The age of consent for HCT services in Zambia is 16 years (35); those younger encountered more obstacles to HCT around obtaining parental consent. This supports the need to engage parents and increase their awareness of the benefits of HCT (21, 36). The younger adolescent found to be HIV-positive are most likely to have been perinatally infected, and although the relative numbers are thought to be small, may represent a specific group to target for alternative routes of offering testing, for example through parents’ ART clinics.

Contextual factors have been shown to influence uptake of interventions like HCT. Detailed description of contextual differences in our communities is described elsewhere (23). High levels of HIV sensitisation programs conducted by NGOs have been observed in community Z5, potentially contributing to the high HCT uptake (23). Community Z5 is dominated by a largely informal sector, where access to clinics and services may be limited due to poverty and testing options situated outside the community (23).

Interestingly, we show that household composition influences HCT uptake. In females, having an HIV-positive household member (young or older adult) was associated with higher HCT uptake and to our knowledge has not been demonstrated before in this age group. This finding supports the need for intensifying HIV index case testing for adolescents in households that have an HIV-positive adult. Index case testing of individuals receiving any HIV care or treatment service has been recommended, either through facilities or home-based (37). In adults, index testing has been effective through assisted partner notification services (38–40). In children, index case testing has been shown to have a 10-fold increase in the identification and enrolment of HIV-infected children into paediatric care and treatment services (41). However, there is little known about the feasibility of index case testing amongst adolescents. This finding emphasises the potential role index case testing could have among adolescents, and the need for further research.

In this study, the intervention increased opportunities to engage and influence other family members as adolescents living in households with at least an additional member previously tested by CHiPs had higher odds of accepting HCT; as reported elsewhere (15).

Although few adolescents reported STI symptoms, females symptomatic for STIs were more likely to test for HIV. Previous research on this is mixed: in Mwanza, Tanzania, STI symptoms did not correlate with HCT uptake (42), while another study in Tanzania showed an association between testing uptake and STI symptoms (43). These mixed results may be due to the challenging nature of self-reporting of STI symptoms and the perceived increased risk of HIV acquisition. Males who had received VMMC had higher HCT uptake; it is hypothesised that individuals who are more likely to have VMMC may be more willing to accept medical interventions, including HCT.

Limitations

In this study, ‘first 90’ was not quite reached partly due to challenges around parental consent; parents were often not found at home, or were not willing to provide consent for younger adolescents. The intervention is resource intensive and the overall cost-effectiveness will not be available until trial completion. It may be more feasible to deliver streamlined and targeted youth-friendly approaches for different age bands and sex similar to index-case based testing programs (37). Furthermore, data was only analysed from the intervention Arm A Communities, without comparison to the control communities, where data is not yet available. However, since the majority of adolescents tested through the intervention, we feel confident in attributing the large rise in HCT to the intervention. However, migration and mobility are key challenges which are currently being analysed.

Conclusions

Through a home-based approach of offering a combination HIV prevention package the proportion of adolescents who knew their HIV status increased from ~28% to 89%, approaching the target goal of 90%. This study provides strong evidence that HB-HCT is feasible, acceptable and effective at significantly increasing HCT uptake among adolescents aged 15–19. HB-HCT is an effective intervention to increase the uptake of the first of UNAIDS 90-90-90 targets amongst adolescents and could be particularly effective if implemented in combination with targeted testing.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the HPTN 071 (PopART) and P-ART-Y study teams

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIAID, NIMH, NIDA, PEPFAR, 3ie, or the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. We are grateful to all members of the HPTN 071 (PopART) and P-ART-Y Study Teams, and to the study adolescents and their communities, for their contributions to the research.

Funding:

HPTN 071 is sponsored by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) under Cooperative Agreements UM1-AI068619, UM1-AI068617, and UM1-AI068613, with funding from the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). Additional funding is provided by the International Initiative for Impact Evaluation (3ie) with support from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, as well as by NIAID, the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) and the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), all part of the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH).

The P-ART-Y study is funded by Evidence for HIV Prevention in Southern Africa (EHPSA), a Department for International Development (DFID) programme managed by Mott MacDonald.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

KS took the lead on writing the paper together with MJC and CM-Y. AS led on the statistical analysis together with SF. All other authors were involved in the design and implementation of the study; provided guidance and approved the final version of the paper.

References

- 1.UNAIDS. 90-90-90 An ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.UNAIDS. AIDS Epidemic. Update. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO. HIV and Adolescents: Guidance for HIV Testing and Counselling and Care for Adolescents Living with HIV: Recommendations for a Public Health Approach and Considerations for Policy-Makers and Managers. 2013 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antony Lake and Michel Sidibé. To end the AIDS epidemic, start focusing on adolescents. UNAIDS; 2015. Available from: http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/presscentre/featurestories/2015/february/20150217_oped_all-in. [Google Scholar]

- 5.UNICEF. Global HIV Database. 2014 Available from: http://data.unicef.org/hiv-aids/global-trends.

- 6.UNICEF. Statistical Update: Children, Adolescents and AIDS. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 7.United Nations Children’s Fund. For Every Child, End AIDS – Seventh Stocktaking Report. New York: Dec, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosenberg NE, Hauser BM, Ryan J, Miller WC. The effect of HIV counselling and testing on HIV acquisition in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2016;92(8):579. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2016-052651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Central Statistical Office (CSO), Ministry of Health (MoH), Zambia and ICF International. Zambia Demographic and Health Survey 2013–14. Rockville, Maryland, USA: Central Statistical Office, Ministry of Health, and ICF International; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramirez-Avila L, Nixon K, Noubary F, Giddy J, Losina E, Walensky RP, et al. Routine HIV Testing in Adolescents and Young Adults Presenting to an Outpatient Clinic in Durban, South Africa. PLOS ONE. 2012;7(9):e45507. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.WHO. The Voices, Values and Preference of Adolescents on HIV Testing and Counselling. 2013 Available from: http://www.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/95143/1/WHO_HIV_2013.135_eng.pdf.

- 12.Sisay S, Erku W, Medhin G, Woldeyohannes D. Perception of High School Students on risk for acquiring HIV and utilization of Voluntary Counseling and Testing (VCT) service for HIV in Debre-berhan Town, Ethiopia: a quantitative cross-sectional study. BMC Research Notes. 2014;7(1):518. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-7-518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.MacPhail CL, Pettifor A, Coates T, Rees H. “You Must Do the Test to Know Your Status”: Attitudes to HIV Voluntary Counseling and Testing for Adolescents Among South African Youth and Parents. Health Education & Behavior. 2006;35(1):87–104. doi: 10.1177/1090198106286442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferrand RA, Trigg C, Bandason T, Ndhlovu CE, Mungofa S, Nathoo K, et al. Perception of Risk of Vertically Acquired HIV Infection and Acceptability of Provider-Initiated Testing and Counseling Among Adolescents in Zimbabwe. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;101(12):2325–32. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kroeger K, Taylor AW, Marlow HM, Fleming DT, Beyleveld V, Alwano MG, et al. Perceptions of door-to-door HIV counselling and testing in Botswana. SAHARA-J: Journal of Social Aspects of HIV/AIDS. 2011;8(4):171–8. doi: 10.1080/17290376.2011.9725001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Denison JA, McCauley AP, Dunnett-Dagg WA, Lungu N, Sweat MD. The HIV testing experiences of adolescents in Ndola, Zambia: do families and friends matter? AIDS Care. 2008;20(1):101–5. doi: 10.1080/09540120701427498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Denison JA, McCauley AP, Dunnett-Dagg WA, Lungu N, Sweat MD. HIV Testing among Adolescents in Ndola, Zambia: How Individual, Relational, and Environmental Factors Relate to Demand. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2009;21(4):314–24. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2009.21.4.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Godia PM, Olenja JM, Hofman JJ, van den Broek N. Young people’s perception of sexual and reproductive health services in Kenya. BMC Health Services Research. 2014;14(1):172. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Philbin MM, Tanner AE, DuVal A, Ellen JM, Xu J, Kapogiannis B, et al. Factors affecting linkage to care and engagement in care for newly diagnosed HIV-positive adolescents within fifteen adolescent medicine clinics in the United States. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(8):1501–10. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0650-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cowan FM, Pascoe SJS, Langhaug LF, Mavhu W, Chidiya S, Jaffar S, et al. The Regai Dzive Shiri Project: results of a randomised trial of an HIV prevention intervention for Zimbabwean youth. AIDS (London, England) 2010;24(16):2541–52. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833e77c9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sam-Agudu NA, Folayan MO, Ezeanolue EE. Seeking wider access to HIV testing for adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa. Pediatr Res. 2016;79(6):838–45. doi: 10.1038/pr.2016.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hayes R, Ayles H, Beyers N, Sabapathy K, Floyd S, Shanaube K, et al. HPTN 071 (PopART): Rationale and design of a cluster-randomised trial of the population impact of an HIV combination prevention intervention including universal testing and treatment - a study protocol for a cluster randomised trial. Trials. 2014;15(1):57. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bond V, Chiti B, Hoddinott G, Reynolds L, Schaap A, Simuyaba M, et al. “The difference that makes a difference”: highlighting the role of variable contexts within an HIV Prevention Community Randomised Trial (HPTN 071/PopART) in 21 study communities in Zambia and South Africa. AIDS Care. 2016;28(sup3):99–107. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2016.1178958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Govindasamy D, Ferrand RA, Wilmore SMS, Ford N, Ahmed S, Afnan-Holmes H, et al. Uptake and yield of HIV testing and counselling among children and adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2015;18(1):20182. doi: 10.7448/IAS.18.1.20182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lugada E, Levin J, Abang B, Mermin J, Mugalanzi E, Namara G, et al. Comparison of home and clinic-based HIV testing among household members of persons taking antiretroviral therapy in Uganda: results from a randomized trial. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes. 2010;55(2):245–52. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181e9e069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kankasa C, Carter RJ, Briggs N, Bulterys M, Chama E, Cooper ER, et al. Routine offering of HIV testing to hospitalized pediatric patients at university teaching hospital, Lusaka, Zambia: acceptability and feasibility. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes. 2009;51(2):202–8. doi: 10.1097/qai.0b013e31819c173f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wei CHA, Raymond HF, Anglemyer A, Gerbase A, Noar SM. Social marketing interventions to increase HIV/STI testing uptake among men who have sex with men and male-to-female transgender women. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2011;9:CD009337. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morin SF, Khumalo-Sakutukwa G, Charlebois ED, Routh J, Fritz K, Lane T, et al. Removing Barriers to Knowing HIV Status: Same-Day Mobile HIV Testing in Zimbabwe. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2006;41(2):218–24. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000179455.01068.ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Atomo Diagnostics. [15th April 2017];Desmond Tutu HIV Foundation study finds HIV self-testing highly acceptable for adolescent use. 2016 Available from: http://atomodiagnostics.com/desmond-tutu-hiv-foundation-study-finds-hiv-self-testing-highly-acceptable-for-adolescent-use/

- 30.Santelli JS, Edelstein ZR, Mathur S, Wei Y, Zhang W, Orr MG, et al. Behavioral, Biological, and Demographic Risk and Protective Factors for New HIV Infections among Youth, Rakai, Uganda. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 2013;63(3):393–400. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182926795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harling G, Newell M-L, Tanser F, Bärnighausen T. Partner age-disparity and HIV incidence risk for older women in rural South Africa. AIDS and behavior. 2015;19(7):1317–26. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0952-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Amornkul PN, Vandenhoudt H, Nasokho P, Odhiambo F, Mwaengo D, Hightower A, et al. HIV Prevalence and Associated Risk Factors among Individuals Aged 13–34 Years in Rural Western Kenya. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(7):e6470. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Birdthistle I, Mayanja BN, Maher D, Floyd S, Seeley J, Weiss HA. Non-consensual Sex and Association with Incident HIV Infection Among Women: A Cohort Study in Rural Uganda, 1990–2008. AIDS and Behavior. 2013;17(7):2430–8. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0378-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Watts C, Seeley J. Addressing gender inequality and intimate partner violence as critical barriers to an effective HIV response in sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2014;17(1):19849. doi: 10.7448/IAS.17.1.19849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ministry of Health, National HIV/AIDS/STI/TB Council. Zambia National Guidelines for HIV Counseling & Testing of Children. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Denison JA, McCauley AP, Lungu N, Sweat MD. Families matter: Social relationships and adolescent HIV testing behaviors in Ndola, Zambia. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies. 2014;9(2):132–8. [Google Scholar]

- 37.PEPFAR. Strategies for Identifying and Linking HIV-Infected Infants, Children, and Adolescents to HIV Care and Treatment. 2013 Available from: www.pepfar.gov/documents/organization/244347.pdf.

- 38.Cherutich P, Golden MR, Wamuti B, Richardson BA, Ásbjörnsdóttir KH, Otieno FA, et al. Assisted partner services for HIV in Kenya: a cluster randomised controlled trial. The Lancet HIV. 2016;4(2):e74–e82. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(16)30214-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brown LB, Miller WC, Kamanga G, Nyirenda N, Mmodzi P, Pettifor A, et al. HIV partner notification is effective and feasible in sub-Saharan Africa: Opportunities for HIV treatment and prevention. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 2011;56(5):437–42. doi: 10.1097/qai.0b013e318202bf7d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rosenberg NE, Mtande TK, Saidi F, Stanley C, Jere E, Paile L, et al. Recruiting male partners for couple HIV testing and counselling in Malawi’s option B+ programme: an unblinded randomised controlled trial. The lancet HIV. 2015;2(11):e483–e91. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(15)00182-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim MH, Ahmed S, Buck WC, Preidis GA, Hosseinipour MC, Bhalakia A, et al. The Tingathe programme: a pilot intervention using community health workers to create a continuum of care in the prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV (PMTCT) cascade of services in Malawi. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2012;15(Suppl 2):17389. doi: 10.7448/IAS.15.4.17389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Isingo R, Wringe A, Todd J, Urassa M, Mbata D, Maiseli G, et al. Trends in the uptake of voluntary counselling and testing for HIV in rural Tanzania in the context of the scale up of antiretroviral therapy. Trop Med Int Health. 2012;17(8):e15–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02877.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mahande MJ, Phimemon RN, Ramadhani HO. Factors associated with changes in uptake of HIV testing among young women (aged 15–24) in Tanzania from 2003 to 2012. Infect Dis Poverty. 2016;5(1):92. doi: 10.1186/s40249-016-0180-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]