Abstract

Background

The human sulfatase 1 (SULF1) and sulfatase 2 (SULF2) genes modulate cell signaling and homeostasis in many tissues. Gene expression analyses have implicated SULF2 in disease pathogenesis, including Alzheimer’s disease (AD), but changes in brain SULF2 expression have not been directly established.

Objective

To investigate the expression of SULF1 and SULF2 in brain tissues from AD cases and cognitively normal controls.

Methods

Autopsy tissue from AD cases (n = 20) and age-and gender-matched cognitively normal controls (n = 20) were identified from the Mayo Clinic Alzheimer’s Disease Patient Registry neuropathology database. Tissue slides were stained for SULF1 and SULF2 protein expression in the hippocampus and frontal lobe and an expression score computed from the proportion of cells stained and the intensity of staining (range 0 [no expression] to 9 [marked expression]).

Results

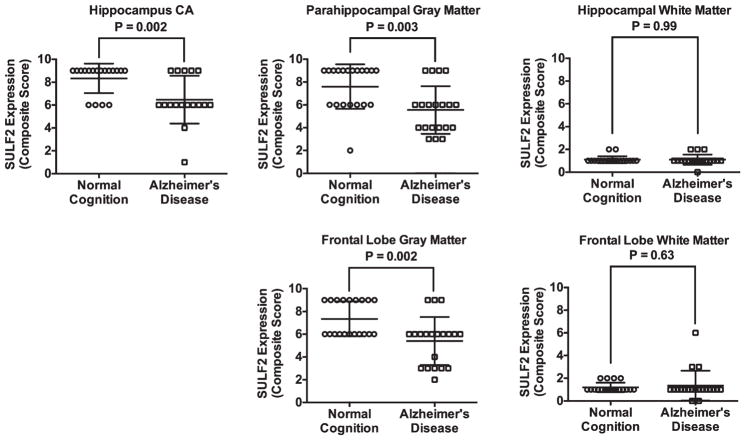

SULF2 expression was reduced in AD cases. Compared to cognitively normal controls, SULF2 expression in AD cases was significantly decreased in the hippocampal Cornu Ammonis (CA) (mean score of 6.5 in cases versus 8.3 in controls; p = 0.003), in the gray matter of the parahippocampal gyrus (5.6 in cases versus 7.6 in controls; p = 0.003), and in the frontal lobe gray matter (5.4 in cases versus 7.4 in controls; p = 0.002). There was no difference in SULF1 expression in the hippocampus or frontal lobe of AD cases and controls. As expected there were no differences in SULF1 or SULF2 expression in white matter in AD cases compared to cognitively normal controls.

Conclusion

Decresed SULF2 in specific regions of the brain occurs in AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, cognition, heparan sulfate proteoglycans, hSulf2, neuropathology, SULF2

INTRODUCTION

Dementias, of which Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common, carry a substantial public health impact. Of the 5.4 million people with AD dementia in US, 5.2 million are aged 65 and older and 200,000 are less than 65 years old [1]. AD dementia is highly prevalent among older people: the prevalence increases from <1% in people aged less than 65 years old, to 3% in 65–74 year olds, 17% in 75–84 year olds, to 32% in people 85 years and older [2]. With 10,000 baby boomers reaching age 65 years every day, the number of people with AD dementia is projected to reach 13.8 million by 2050, with an estimated 1 million new cases per year [1]. Furthermore, AD dementia is the sixth leading cause of death in the US (5th among people aged 65 years and older) [3]. Efforts to reduce the burden of dementia rest in part on understanding the pathophysiology of AD. Magnetic resonance imaging indicates that atrophy in the hippocampal formation is common in AD [4, 5]. Studies in animals and humans show decreased neurogenesis in the hippocampus with age [6–9]. Synaptic plasticity also is dependent on the regulation of neurite outgrowth (neuritogenesis) [10, 11].

Neurogenesis and neuritogenesis are regulated by extracellular growth factors that control cell signaling [12]. The extracellular matrix contains proteoglycans comprised of core proteins with attached glycosaminoglycan (GAG) moieties, including heparan sulfate (HS) and chondroitin sulfate (CS) GAG chains. HS chains regulate the concentration and activity of several heparin-binding proteins (cytokines and growth factors). These include fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF-2), a key mediator of neurogenesis [13], and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which regulates synaptic transmission and synaptic plasticity [14]. In addition, HS is associated with amyloid-β plaques [15].

The effects of heparin-binding proteins on cell signaling are dependent on the sulfation of HS chains and on the effects of HS sulfatases in the extracellular matrix. HS sulfation occurs at the 2-O, 3-O, and 6-O positions of the core HS disaccharide. Changes in sulfation of HS chains can alter the binding of HS to heparin-binding proteins, with varying effects on cell signaling. Particular HS sulfation patterns have been associated with brain development, angiogenesis, cancer, and AD [16–20]. Sulfatase 1 (SULF1) and sulfatase 2 (SULF2) are extracellular sulfatases that desulfate 6-O-sulfate groups on HS and thereby modulate growth factor and cell signaling, cell growth, development and differentiation, and homeostasis [16, 21, 22]. Somewhat paradoxically, SULF1 and SULF2 do not always have the same effect on cell signaling pathways. They have been shown to have opposing actions on some angiogenesis and growth factor signaling pathways, such as the FGF2 signaling pathway. Thus, whereas SULF1 mitigates FGF2 signaling, SULF2 enhances FGF2 signaling [23]. However, in contrast to their opposing effects on FGF signaling, both SULF1 and SULF2 activate Wnt and TGFβ signaling which are important signaling pathways in development, differentiation, and carcinogenesis [24, 25].

Rat Sulf2 is expressed in different regions of the nervous system during development, but is confined to the cerebral cortex, hippocampal CA3 region, and medial habenular nucleus in the adult brain [26]. Changes in Sulf1 and Sulf2 expression modulate sulfation of glial cell HS and regulate FGF1 and FGF9 signaling in glial cells and control nervous system repair in rats [27] and mice [28]. While Sulf1 and Sulf2 are expressed in many different types of neurons in the nervous system, there are differences in their regional distribution, subcellular localization, and glycosylation in different parts of the nervous system [29].

It is hypothesized that changes in HS during aging may impact heparin-binding protein function. Higher levels of HSGAGs but not CSGAGs have been found in aged versus adult human hippocampal cells, particularly in regions with amyloid plaques [30]. Our previous work has also shown that certain genes differentially expressed in correlation with SULF2 are associated with AD and Lewy body dementia [24]. This body of knowledge suggests that changes in sulfatase expression could impair neurogenesis, neuritogenesis, and cell repair in the hippocampal formation and contribute to the pathogenesis of AD, and that this effect may, in turn, be regulated by the sulfatase genes. To determine whether sulfatase expression is related to AD pathology, we compared expression of SULF1 and SULF2 in autopsy specimens of subjects with and without AD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects and autopsy specimens

All subjects had been enrolled in the community-based Mayo Alzheimer’s Disease Patient Registry (ADPR) [31–33]. Prior to death, all study subjects underwent annual cognitive testing and evaluation by a team of behavioral neurologists and neuropsychologists at the Mayo Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center to establish a diagnosis of AD based on published criteria or cognitively normal according to normative data from the Olmsted County population [34–39]. We identified subjects who died between 1999 and 2008 (n = 20) through the Mayo Clinic Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center neuropathology database and had a clinical diagnosis and neuropathological confirmation of AD. They were age and gender-matched with ADPR (n = 20) subjects who died within the same period as the case and were cognitively and pathologically normal.

Neuropathology

Postmortem brains of subjects were processed using standardized neuropathologic methods [40]. An experienced neuropathologist assessed a diagnosis of AD or normal pathology according to the CERAD rating scheme for plaques, NIA-Reagan criteria, and Braak and Braak staging [40–45]; Thal staging was not a part of the staging protocol at the time of this study.

Detection of SULF1 and SULF2

The antibodies used for immunohistochemical staining for SULF1 and SULF2 were rabbit polyclonal antibodies raised against peptides from human SULF1 (amino acids 677–699: CSKQSY YNKEKGVKKQEKLKSHL, Genbank accession number NM 015170) and SULF2 (amino acids 421–444: HKRDNDKVDAQEENFLPKYQRVKD, Genbank accession number NM 018837) which recognize human, mouse and rat SULF1 or SULF2, respectively [25, 46–49]. Detection of SULF1 and SULF2 expression was performed on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples which were deparaffinized with 3 changes of xylene, rehydrated in a series of alcohols (100%, 95%, then 70% EtOH), and rinsed well in running distilled water. Slides were placed in preheated 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0 retrieval buffer for 30 min then cooled in the buffer for 5 min followed by a 5-min rinse in running distilled water. After the heat inactivated epitope retrieval (HIER) step, slides were placed on the DAKO Autostainer at room temperature. Sections were incubated with 3% H2O2 in ethanol for 5 min to inactivate endogenous peroxides. Sections were incubated in anti-SULF1 polyclonal antibody (1 : 150) or anti-SULF2 polyclonal antibody (1 : 100) for 30 min followed by rinsing with Tris Buffered Saline with Tween 20 (Polysorbate 20) (TBST) wash buffer and then incubated for 15 min in secondary antibody ADVANCE HRP polymer (DAKO Cytomation, Carpenteria, CA). Sections were then rinsed with TBST wash buffer, incubated in 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB+)(DAKO Cytomation, Carpenteria, CA) for 5 min, and counterstained with Modified Schmidt’s Hematoxylin for 5 min. The sections were then rinsed in tap water for 3 min, dehydrated through graded alcohols, cleared in 3 changes of xylene, and mounted with permanent mounting media. Positive and negative controls confirming specificity of the immunostaining using small intestine are shown in Supplementary Figure 1. Negative controls were set up by replacement of the primary antibody with 1% BSA-TBS. All negative control specimens showed no non-specific staining.

Assessment of SULF expression

Each stained slide was reviewed by a pathologist (Y.N.K.) to assess expression of SULF1 and SULF2 in the hippocampus (including the entire CA region) and frontal lobe. The proportion of cells stained was scored as: no staining = 1, <25% = 2, 26–50% = 3, >50% = 4. The intensity of staining was scored as: none = 0, weak = 1, moderate = 2, and strong = 3. SULF expression was computed as the product of the proportion of cells stained and the intensity of staining; the scores ranged from 0 to 9 (none = 0, weak = 1, moderate = 2, marked = 4, 6, or 9). In the regions with a predominance of neurons, the neuronal staining was the major contributor to the scoring, whereas in the regions with a predominance of glial cells in the white matter, staining of the glial cells was scored. The neuropathologist who reviewed the autopsy specimen, the technologist who stained the slides and the pathologist who scored SULF1 and SULF2 expression were blinded to the diagnosis of the subjects.

Statistics

We compared AD cases and cognitively normal controls in regard to expression of SULF1 and SULF2 in the gray and white matter of the hippocampus and frontal lobe using the non-parametric Wilcoxon rank sum test (SAS version 9, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

The mean age (standard deviation) of subjects at autopsy was 86.6 (SD = 6.24). Consistent with the matching design there was no difference in the mean age between cases (86.9 [6.3]) and cognitively normal controls (86.4 [6.4]) (Table 1). There were also equal proportions of women (n = 13 [65%]) in the AD cases and cognitively normal controls (Table 1). The distribution of Braak staging was stage V (n = 4, 20%) or VI (16, 80%) in AD cases, and stage I (n = 8, 40%), II (n = 7, 35%) or III (n = 5, 25%) in cognitively normal controls. The NIA Reagan criteria score was high in all AD cases, and negative or low in cognitively normal controls.

Table 1.

Demographics, SULF1, and SULF2 measurements by cognitive status

| Normal Cognition n = 20 |

Alzheimer’s Disease n = 20 |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y mean (SD) | 86.4 (6.4) | 86.9 (6.3) | |

| Sex, % women | 65% | 65% | |

| SULF2* | |||

| Hippocampus | |||

| CA | 8.33 (1.28) | 6.44 (2.04) | 0.003 |

| Gray matter | 7.60 (1.96) | 5.55 (2.09) | 0.003 |

| White matter | 1.10 (0.31) | 1.10 (0.45) | 0.99 |

| Frontal | |||

| Gray matter | 7.35 (1.53) | 5.40 (2.11) | 0.002 |

| White matter | 1.20 (0.41) | 1.35 (1.31) | 0.63 |

| SULF1* | |||

| Hippocampus | |||

| CA | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.99 |

| Gray matter | 1.35 (1.35) | 1.40 (1.31) | 0.91 |

| White matter | 2.00 (1.75) | 1.50 (1.36) | 0.32 |

| Frontal | |||

| Gray matter | 1.20 (1.51) | 1.30 (1.12) | 0.81 |

| White matter | 1.15 (1.35) | 1.45 (1.43) | 0.50 |

| Braak staging, n (%) | |||

| I | 8 (40.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| II | 7 (35.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| III | 5 (25.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| IV | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| V | 0 (0.0) | 4 (20.0) | |

| VI | 0 (0.0) | 16 (80.0) | |

Composite immunohistochemistry score: proportion of cells stained by intensity of staining.

SULF2 expression

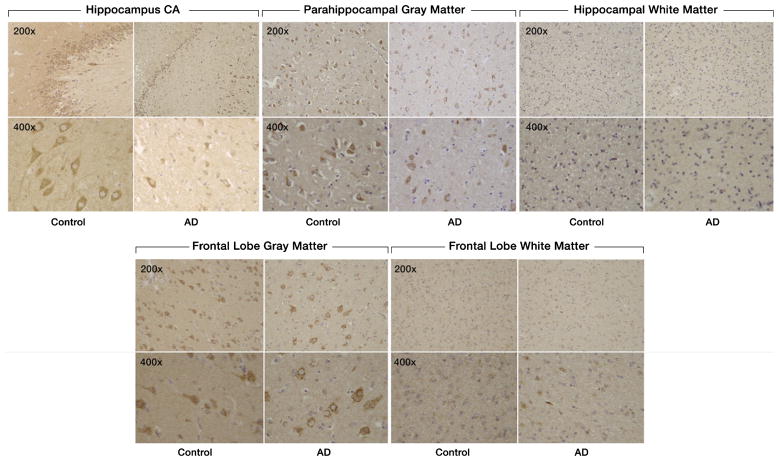

There was decreased staining of SULF2 in AD cases compared to cognitively normal controls in the hippocampus and in the frontal lobe (Fig. 1). Compared to cognitively normal controls, the expression of SULF2 in AD cases was significantly lower in the hippocampal CA region (mean score in cases: 6.5 versus 8.3 in controls; p = 0.003), in the parahippocampal gray matter (mean score in cases: 5.6 versus 7.6 in controls; p = 0.003), and in the frontal lobe gray matter (5.4 versus 7.4 in controls; p = 0.002) (Fig. 2). However, as expected, there was no difference in SULF2 expression in the white matter of the hippocampus or the frontal lobe (Fig. 2). This is expected as there is minimal AD pathology in the white matter.

Fig. 1.

Expression of SULF2 in AD and cognitively normal control brain tissue. Immunohistochemical staining of SULF2 in the hippocampus and frontal lobe. There is less density of staining and a smaller proportion of cells are stained in the hippocampus CA and parahippocampal gray matter, as well as in the frontal lobe gray matter, in AD cases compared to cognitively normal controls. The quantification of SULF2 staining in the CA region encompassed the entire CA region, including CA1.

Fig. 2.

Plots of mean (standard deviation) scores for SULF2 expression in cases and cognitively normal controls. In the hippocampus, the mean score was lower in the CA for AD cases (6.5 [2.0]) compared to cognitively normal controls (8.3 [1.3]; p = 0.003). Similarly, the expression of SULF2 in the parahippocampal gray matter was lower in AD cases (5.6 [2.1]) than in cognitively normal controls (7.6 [2.0]; p = 0.003) and the expression of SULF2 in the frontal gray matter was lower in AD cases (5.4 [2.1]) than in cognitively normal controls (7.4 [1.5]; p = 0.002). There was no difference in SULF2 expression in the white matter of the hippocampus or the frontal lobe.

SULF1 expression

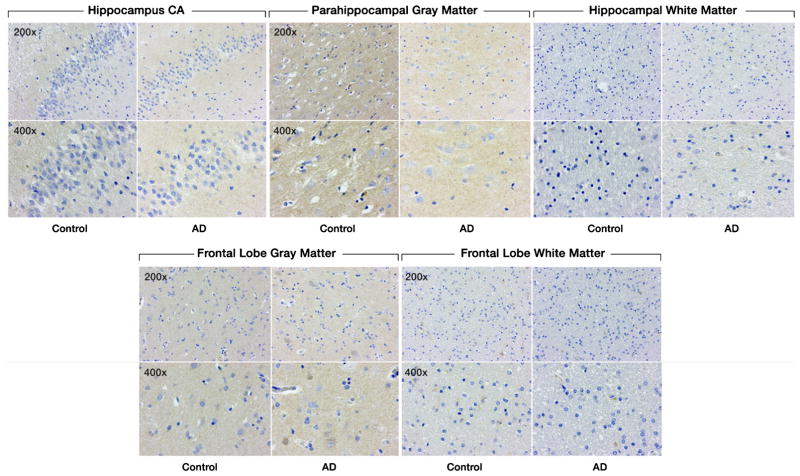

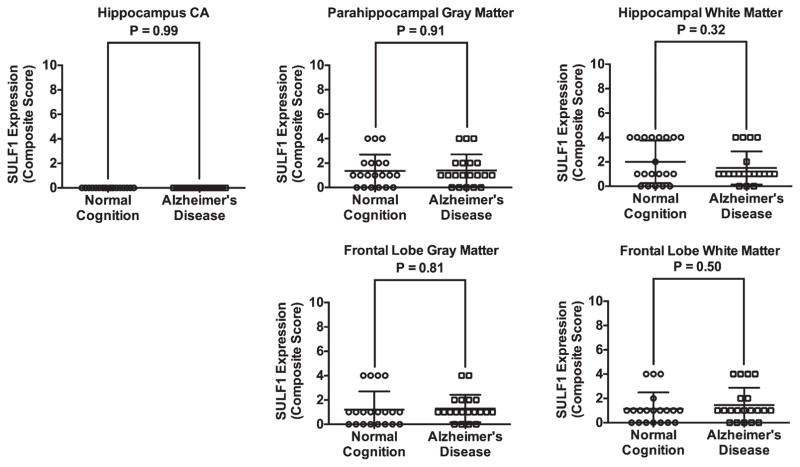

There was no significant difference in SULF1 staining (Fig. 3) or expression between AD cases and cognitively normal controls in either the hippocampal or frontal lobe gray or white matter (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Expression of SULF1 in AD and cognitively normal control brain tissue. Immunohistochemical staining of SULF1 in the hippocampus and frontal lobe. There is no staining by SULF1 in the hippocampus CA, parahippocampal gray matter, frontal lobe gray matter in AD or cognitively normal control brain tissue. The quantification of SULF1 staining in the CA region encompassed the entire CA region, including CA1.

Fig. 4.

Plots of mean (standard deviation) scores for SULF1 expression in cases and cognitively normal controls. There was no difference in SULF1 expression in any of the brain regions examined.

DISCUSSION

Decreased expression of SULF2 in the hippocampal CA and parahippocampal gray matter and the frontal lobe gray matter was observed in AD cases. These findings are consistent with the recent report of an increase in highly sulfated HS domains that are susceptible to digestion by SULF1 and SULF2 in the brains of transgenic AD mouse models as well as in human AD brains [50]. These observations are also consistent with a model in which decreased expression of SULF2 may be involved in the pathology of AD, and may contribute to changes in memory and executive function.

Our findings are consistent with the suggestion that decreased expression of SULF2 may promote the development of AD by enhancing sulfation of heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs). Increase in extracellular highly sulfated HS may result in increased sequestration of the available extracellular growth factors away from their cognate receptors, leading to decreased signaling. HSPGs are also hypothesized to impact the pathogenesis of AD through effects on amyloid-β protein precursor (AβPP). HSPGs have been demonstrated in amyloid plaques, the hallmark of AD pathology [51–56]. Binding of AβPP to HSPGs stimulates neurite outgrowth [57–59]. Thus, abnormal interactions of AβPP with HSPGs may alter AβPP function, and enhance the production and deposition of amyloid-β [59].

Other studies have demonstrated that HSPGs but not CSPGs reduce amyloid-β aggregation and toxicity [15, 60, 61]. Thus, structural and functional changes in HSPGs in elderly subjects may decrease binding and activity of growth factors, reduce neurogenesis, neuritogenesis, and angiogenesis, and may result in increased amyloid-β toxicity and development of AD.

In terms of the specific locations of changes in HSPGs, one study found an increase in HSPGs in the hippocampus of subjects with AD, suggesting a role for HSPGs in AD pathogenesis [62]. Another study of HS expression in the hippocampus of aged (mean age 66 years) versus adult (mean age 28 years) subjects demonstrated structural changes in HS in the hippocampus of aged subjects. These changes included decreased 2-O-sulfation, and increased N- and 3-O sulfation, but no difference in 6-O-sulfation [30]. Compared to GAGs from adult brains, GAGs from aged brains had decreased binding to growth factors, and decreased ability to enhance growth factor proliferative activity. With suppression of endogenous BDNF, aged hippocampus GAGs promoted neuritogenesis in neuroblastoma cells. However, there was no difference in the ability of aged versus adult HSPGs to protect cells against amyloid-β toxicity [30].

HSPG gene polymorphisms may be effect modifiers of risk for AD. In a genetic association study, there was no association of the HSPG2 (perlecan) gene with AD overall [63]. However, in APOE ε4 carriers the HSPG2 A allele was associated with an increased risk of AD. Another study, however, did not observe associations of HSPG2 gene polymorphisms with AD [64]. Nonetheless, since the interactions of growth factors with HSPG vary by the HSPG type, the associations with AD may also vary across HSPGs.

The association of decreased SULF2, but not SULF1, expression in the brain regions implicated in AD is consistent with our previous findings. Genes correlated with SULF2 gene expression in liver cancers had strong associations with familial amyloid neuropathies, early onset AD, and Lewy body dementia [24]. Similar associations were not found in genes correlating with SULF1 expression [24].

Gene knockout studies showed that although Sulf2 and Sulf1 are both involved in the development of mouse brain, mouse Sulf2 deficiency was associated with more severe phenotypes than Sulf1 deficiency. Sulf2 knockout mice had greater embryonic mortality, but no developmental abnormalities were observed in Sulf1 knockout mice [65]. Both Sulf1 and Sulf2 single-knockout mice showed deficits in neurite length in hippocampal and cerebellar neurons, and there were deficits in synaptic plasticity in the CA1 region of the hippocampus in Sulf1 knockout mice suggesting that Sulf1 may also be involved in neural development [65]. Another study found higher levels of Sulf2 than Sulf1 in the brains of wild-type mice [66]. Knockout of Sulf1 or Sulf2 resulted in similar increases of approximately 20% in the brain concentration of trisulfated HS disaccharides, the major substrate for both sulfatases, however, the expression of Sulf1 and Sulf2 and the concentrations of trisulfated HS disaccharides in specific regions of the brain were not assessed [66]. More recent studies in the cerebellum of newborn mice including HS analyses suggest that the sulfatases may impact postnatal developmental processes through their specific and differential effects on HS chains, resulting in differences in signaling by FGF-2, glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF), and nerve growth factor (NGF) that are quite complex [67]. FGF2 and GDNF appear to mediate Sulf2-dependent neurite outgrowth. By contrast, neither FGF2, GDNF, nor NGF appears capable of mediating Sulf1-dependent neurite outgrowth. Instead, GDNF appears to act in concert with SULF1 to inhibit cell survival and proliferation of granule precursor cells in the external granular cell layer. Functionally, the studies show that the behavioral effects of Sulf2 and Sulf1 differ; whereas Sulf2 deficiency adversely impacts spatial learning performance, Sulf1 deficiency impacts nocturnal perambulation [65, 67].

Our study has certain limitations that need to be taken into account. The sample size was small, and quantification of Sulf1 and Sulf2 staining was not robust. Specifically, scoring was performed by eye, by a single reviewer, and the scoring was not based on a proven methodology. Neuronal density in the CA1 region was not assessed and adjusted to definitively distinguish between decreased SULF2 expression and non-specific AD-related loss of neuronal cells. However, these exploratory findings should generate hypotheses to be validated in definitive studies with larger sample sizes. Thal staging for AD was not assessed since this was not part of the study protocol at the time.

Our findings suggest that decreased SULF2 expression in specific regions of the hippocampus and the frontal lobe is seen in patients with AD, and may be involved in the pathogenesis of AD. These findings should be confirmed in larger studies. If they are confirmed, future studies should investigate the mechanisms for loss of SULF2 expression in AD, the stage of cognitive decline during which SULF2 is lost, and whether modulation of expression or activity of SULF2 can mitigate cognitive decline.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants P50 AG016574, U01 AG006786, K01 AG028573, and CA165076; the Mayo Clinic Center for Cell Signaling in Gastroenterology (NIDDK P30 DK084567); the Mayo Clinic Cancer Center (CA15083), and the Mayo Clinic Center for Translational Science Activities (NCATS CTSA UL1 TR000135). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. The authors thank Dr. Joseph E. Parisi (neuropathologist) for critical review of the manuscript and Ms. Jennifer Rud for secretarial assistance.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflict of interest to report.

The supplementary material is available in the electronic version of this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.3233/ADR-170028.

References

- 1.Alzheimer’s Association. 2016 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12:459–509. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hebert LE, Weuve J, Scherr PA, Evans DA. Alzheimer disease in the United States (2010–2050) estimated using the 2010 census. Neurology. 2013;80:1778–1783. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31828726f5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murphy SL, Kochanek KD, Xu JQ, Heron M. National Vital Statistics Reports. 9. Vol. 63. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, MD: 2015. Deaths: Final data for 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kerchner GA, Deutsch GK, Zeineh M, Dougherty RF, Saranathan M, Rutt BK. Hippocampal CA1 apical neuropil atrophy and memory performance in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroimage. 2012;63:194–202. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.06.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Macdonald KE, Bartlett JW, Leung KK, Ourselin S, Barnes J. The value of hippocampal and temporal horn volumes and rates of change in predicting future conversion to AD. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2013;27:168–173. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318260a79a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gemma C, Bachstetter AD, Cole MJ, Fister M, Hudson C, Bickford PC. Blockade of caspase-1 increases neurogenesis in the aged hippocampus. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;26:2795–2803. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05875.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu P, Gupta N, Jing Y, Zhang H. Age-related changes in polyamines in memory-associated brain structures in rats. Neuroscience. 2008;155:789–796. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kempermann G. The neurogenic reserve hypothesis: What is adult hippocampal neurogenesis good for? Trends Neurosci. 2008;31:163–169. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Revest JM, Dupret D, Koehl M, Funk-Reiter C, Grosjean N, Piazza PV, Abrous DN. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis is involved in anxiety-related behaviors. Mol Psychiatry. 2009;14:959–967. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee SH, Han JH, Choi JH, Huh EY, Kwon YK, Kaang BK. The effect of brain-derived neurotrophic factor on neuritogenesis and synaptic plasticity in Aplysia neurons and the hippocampal cell line HiB5. Mol Cells. 2003;15:233–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sebollela A, Freitas-Correa L, Oliveira FF, Mendes CT, Wasilewska-Sampaio AP, Camacho-Pereira J, Galina A, Brentani H, Passetti F, De Felice FG, Dias-Neto E, Ferreira ST. Expression profile of rat hippocampal neurons treated with the neuroprotective compound 2,4-dinitrophenol: Up-regulation of cAMP signaling genes. Neurotox Res. 2010;18:112–123. doi: 10.1007/s12640-009-9133-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marastoni S, Ligresti G, Lorenzon E, Colombatti A, Mongiat M. Extracellular matrix: A matter of life and death. Connect Tissue Res. 2008;49:203–206. doi: 10.1080/03008200802143190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reuss B, von Bohlen und Halbach O. Fibroblast growth factors and their receptors in the central nervous system. Cell Tissue Res. 2003;313:139–157. doi: 10.1007/s00441-003-0756-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gomez-Palacio Schjetnan A, Escobar-Rodriguez ML. Memory coding and retention: Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in synaptic plasticity. Rev Neurol. 2007;45:409–417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sandwall E, O’Callaghan P, Zhang X, Lindahl U, Lannfelt L, Li JP. Heparan sulfate mediates amyloid-beta internalization and cytotoxicity. Glycobiology. 2010;20:533–541. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwp205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lamanna WC, Kalus I, Padva M, Baldwin RJ, Merry CL, Dierks T. The heparanome–the enigma of encoding and decoding heparan sulfate sulfation. J Biotechnol. 2007;129:290–307. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2007.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guimond S, Turner K, Kita M, Ford-Perriss M, Turnbull J. Dynamic biosynthesis of heparan sulphate sequences in developing mouse brain: A potential regulatory mechanism during development. Biochem Soc Trans. 2001;29:177–181. doi: 10.1042/0300-5127:0290177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ford-Perriss M, Guimond SE, Greferath U, Kita M, Grobe K, Habuchi H, Kimata K, Esko JD, Murphy M, Turnbull JE. Variant heparan sulfates synthesized in developing mouse brain differentially regulate FGF signaling. Glycobiology. 2002;12:721–727. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwf072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scholefield Z, Yates EA, Wayne G, Amour A, McDowell W, Turnbull JE. Heparan sulfate regulates amyloid precursor protein processing by BACE1, the Alzheimer’s beta-secretase. J Cell Biol. 2003;163:97–107. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200303059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang S, Ai X, Freeman SD, Pownall ME, Lu Q, Kessler DS, Emerson CP., Jr QSulf1, a heparan sulfate 6-O-endosulfatase, inhibits fibroblast growth factor signaling in mesoderm induction and angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:4833–4838. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401028101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morimoto-Tomita M, Uchimura K, Werb Z, Hemmerich S, Rosen SD. Cloning and characterization of two extracellular heparin-degrading endosulfatases in mice and humans. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:49175–49185. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205131200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lai JP, Thompson JR, Sandhu DS, Roberts LR. Heparin-degrading sulfatases in hepatocellular carcinoma: Roles in pathogenesis and therapy targets. Future Oncol. 2008;4:803–814. doi: 10.2217/14796694.4.6.803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hammond E, Khurana A, Shridhar V, Dredge K. The role of heparanase and sulfatases in the modification of heparan sulfate proteoglycans within the tumor microenvironment and opportunities for novel cancer therapeutics. Front Oncol. 2014;4:195. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2014.00195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang JD, Sun Z, Hu C, Lai J, Dove R, Nakamura I, Lee JS, Thorgeirsson SS, Kang KJ, Chu IS, Roberts LR. Sulfatase 1 and sulfatase 2 in hepatocellular carcinoma: Associated signaling pathways, tumor phenotypes, and survival. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2011;50:122–135. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dhanasekaran R, Nakamura I, Hu C, Chen G, Oseini AM, Seven ES, Miamen AG, Moser CD, Zhou W, van Kuppevelt TH, van Deursen JM, Mounajjed T, Fernandez-Zapico ME, Roberts LR. Activation of the transforming growth factor-beta/SMAD transcriptional pathway underlies a novel tumor-promoting role of sulfatase 1 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2015;61:1269–1283. doi: 10.1002/hep.27658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nagamine S, Koike S, Keino-Masu K, Masu M. Expression of a heparan sulfate remodeling enzyme, heparan sulfate 6-O-endosulfatase sulfatase FP2, in the rat nervous system. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2005;159:135–143. doi: 10.1016/j.devbrainres.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Higginson JR, Thompson SM, Santos-Silva A, Guimond SE, Turnbull JE, Barnett SC. Differential sulfation remodelling of heparan sulfate by extracellular 6-O-sulfatases regulates fibroblast growth factor-induced boundary formation by glial cells: Implications for glial cell transplantation. J Neurosci. 2012;32:15902–15912. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6340-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ratzka A, Mundlos S, Vortkamp A. Expression patterns of sulfatase genes in the developing mouse embryo. Dev Dyn. 2010;239:1779–1788. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Joy MT, Vrbova G, Dhoot GK, Anderson PN. Sulf1 and Sulf2 expression in the nervous system and its role in limiting neurite outgrowth in vitro. Exp Neurol. 2015;263:150–160. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2014.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huynh MB, Villares J, Diaz JE, Christiaans S, Carpentier G, Ouidja MO, Sissoeff L, Raisman-Vozari R, Papy-Garcia D. Glycosaminoglycans from aged human hippocampus have altered capacities to regulate trophic factors activities but not Abeta42 peptide toxicity. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33:1005e1011–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Petersen RC, Kokmen E, Tangalos E, Ivnik RJ, Kurland LT. Mayo clinic Alzheimer’s disease patient registry. Aging (Milano) 1990;2:408–415. doi: 10.1007/BF03323961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hunderfund AL, Roberts RO, Slusser TC, Leibson CL, Geda YE, Ivnik RJ, Tangalos EG, Petersen RC. Mortality in amnestic mild cognitive impairment: A prospective community study. Neurology. 2006;67:1764–1768. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000244430.39969.5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roberts RO, Geda YE, Knopman DS, Cha RH, Pankratz VS, Boeve BF, Ivnik RJ, Tangalos EG, Petersen RC, Rocca WA. The Mayo Clinic Study of Aging: Design and sampling, participation, baseline measures and sample characteristics. Neuroepidemiology. 2008;30:58–69. doi: 10.1159/000115751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: Report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CR, Jr, Kawas CH, Klunk WE, Koroshetz WJ, Manly JJ, Mayeux R, Mohs RC, Morris JC, Rossor MN, Scheltens P, Carrillo MC, Thies B, Weintraub S, Phelps CH. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ivnik R, Malec J, Smith G, Tangalos E, Petersen R, Kokmen E, Kurland L. Mayo’s older americans normative studies: WMS-R norms for ages 56 to 94. Clin Neuropsychol. 1992;6:49–82. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ivnik R, Malec J, Smith G, Tangalos E, Petersen R, Kokmen E, Kurland L. Mayo’s older americans normative studies: WAIS-R norms for ages 56 to 97. Clin Neuropsychol. 1992;6:1–30. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ivnik R, Malec J, Smith G, Tangalos E, Petersen R, Kokmen E, Kurland L. Mayo’s older americans normative studies: Updated AVLT norms for ages 56 to 97. Clin Neuropsychol. 1992;6:83–104. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Malec J, Ivnik R, Smith G, Tangalos E, Petersen R, Kokmen E, Kurland L. Mayo’s older americans normative studies: Utility of corrections for age and education for the WAIS-R. Clin Neuropsychol. 1992;6:31–47. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mirra SS, Heyman A, McKeel D, Sumi SM, Crain BJ, Brownlee LM, Vogel FS, Hughes JP, van Belle G, Berg L. The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD). Part II. Standardization of the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1991;41:479–486. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.4.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Consensus recommendations for the postmortem diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. The National Institute on Aging, and Reagan Institute Working Group on Diagnostic Criteria for the Neuropathological Assessment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurobiol Aging. 1997;18:S1–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Braak H, Braak E. Diagnostic criteria for neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 1997;18:S85–88. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(97)00062-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Powers JM. Diagnostic criteria for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 1997;18:S53–54. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(97)00070-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Knopman DS, Parisi JE, Salviati A, Floriach-Robert M, Boeve BF, Ivnik RJ, Smith GE, Dickson DW, Johnson KA, Petersen LE, McDonald WC, Braak H, Petersen RC. Neuropathology of cognitively normal elderly. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2003;62:1087–1095. doi: 10.1093/jnen/62.11.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dickson DW, Rogers J. Neuroimmunology of Alzheimer’s disease: A conference report. Neurobiol Aging. 1992;13:793–798. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(92)90104-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lai JP, Yu C, Moser CD, Aderca I, Han T, Garvey TD, Murphy LM, Garrity-Park MM, Shridhar V, Adjei AA, Roberts LR. SULF1 inhibits tumor growth and potentiates the effects of histone deacetylase inhibitors in hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:2130–2144. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.02.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lai JP, Sandhu DS, Yu C, Han T, Moser CD, Jackson KK, Guerrero RB, Aderca I, Isomoto H, Garrity-Park MM, Zou H, Shire AM, Nagorney DM, Sanderson SO, Adjei AA, Lee JS, Thorgeirsson SS, Roberts LR. Sulfatase 2 up-regulates glypican 3, promotes fibroblast growth factor signaling, and decreases survival in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2008;47:1211–1222. doi: 10.1002/hep.22202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shire A, Lomberk G, Lai JP, Zou H, Tsuchiya N, Aderca I, Moser CD, Gulaid KH, Oseini A, Hu C, Warsame O, Jenkins RB, Roberts LR. Restoration of epigenetically silenced SULF1 expression by 5-aza-2-deoxycytidine sensitizes hepatocellular carcinoma cells to chemotherapy-induced apoptosis. Med Epigenet. 2015;3:1–18. doi: 10.1159/000375461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lai JP, Sandhu DS, Yu C, Moser CD, Hu C, Shire AM, Aderca I, Murphy LM, Adjei AA, Sanderson S, Roberts LR. Sulfatase 2 protects hepatocellular carcinoma cells against apoptosis induced by the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 and ERK and JNK kinase inhibitors. Liver Int. 2010;30:1522–1528. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2010.02336.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hosono-Fukao T, Ohtake-Niimi S, Hoshino H, Britschgi M, Akatsu H, Hossain MM, Nishitsuji K, van Kuppevelt TH, Kimata K, Michikawa M, Wyss-Coray T, Uchimura K. Heparan sulfate subdomains that are degraded by Sulf accumulate in cerebral amyloid ss plaques of Alzheimer’s disease: Evidence from mouse models and patients. Am J Pathol. 2012;180:2056–2067. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Perry G, Siedlak SL, Richey P, Kawai M, Cras P, Kalaria RN, Galloway PG, Scardina JM, Cordell B, Greenberg BD, Led-better SR, Gambetti P. Association of heparan sulfate proteoglycan with the neurofibrillary tangles of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 1991;11:3679–3683. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-11-03679.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Siedlak SL, Cras P, Kawai M, Richey P, Perry G. Basic fibroblast growth factor binding is a marker for extracellular neurofibrillary tangles in Alzheimer disease. J Histochem Cytochem. 1991;39:899–904. doi: 10.1177/39.7.1865106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.van Horssen J, Kleinnijenhuis J, Maass CN, Rensink AA, Otte-Holler I, David G, van den Heuvel LP, Wesseling P, de Waal RM, Verbeek MM. Accumulation of heparan sulfate proteoglycans in cerebellar senile plaques. Neurobiol Aging. 2002;23:537–545. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.van Horssen J, Wesseling P, van den Heuvel LP, de Waal RM, Verbeek MM. Heparan sulphate proteoglycans in Alzheimer’s disease and amyloid-related disorders. Lancet Neurol. 2003;2:482–492. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(03)00484-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.O’Callaghan P, Sandwall E, Li JP, Yu H, Ravid R, Guan ZZ, van Kuppevelt TH, Nilsson LN, Ingelsson M, Hyman BT, Kalimo H, Lindahl U, Lannfelt L, Zhang X. Heparan sulfate accumulation with Abeta deposits in Alzheimer’s disease and Tg2576 mice is contributed by glial cells. Brain Pathol. 2008;18:548–561. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2008.00152.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bruinsma IB, te Riet L, Gevers T, ten Dam GB, van Kuppevelt TH, David G, Kusters B, de Waal RM, Verbeek MM. Sulfation of heparan sulfate associated with amyloid-beta plaques in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;119:211–220. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0577-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Small DH, Nurcombe V, Moir R, Michaelson S, Monard D, Beyreuther K, Masters CL. Association and release of the amyloid protein precursor of Alzheimer’s disease from chick brain extracellular matrix. J Neurosci. 1992;12:4143–4150. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-11-04143.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Small DH, Nurcombe V, Reed G, Clarris H, Moir R, Beyreuther K, Masters CL. A heparin-binding domain in the amyloid protein precursor of Alzheimer’s disease is involved in the regulation of neurite outgrowth. J Neurosci. 1994;14:2117–2127. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-04-02117.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Small DH, Williamson T, Reed G, Clarris H, Beyreuther K, Masters CL, Nurcombe V. The role of heparan sulfate proteoglycans in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1996;777:316–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb34439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Timmer NM, Schirris TJ, Bruinsma IB, Otte-Holler I, van Kuppevelt TH, de Waal RM, Verbeek MM. Aggregation and cytotoxic properties towards cultured cerebrovascular cells of Dutch-mutated Abeta40 (DAbeta(1-40)) are modulated by sulfate moieties of heparin. Neurosci Res. 2010;66:380–389. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2009.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Valle-Delgado JJ, Alfonso-Prieto M, de Groot NS, Ventura S, Samitier J, Rovira C, Fernandez-Busquets X. Modulation of Abeta42 fibrillogenesis by glycosaminoglycan structure. FASEB J. 2010;24:4250–4261. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-153551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shimizu H, Ghazizadeh M, Sato S, Oguro T, Kawanami O. Interaction between beta-amyloid protein and heparan sulfate proteoglycans from the cerebral capillary basement membrane in Alzheimer’s disease. J Clin Neurosci. 2009;16:277–282. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Iivonen S, Helisalmi S, Mannermaa A, Alafuzoff I, Lehtovirta M, Soininen H, Hiltunen M. Heparan sulfate proteoglycan 2 polymorphism in Alzheimer’s disease and correlation with neuropathology. Neurosci Lett. 2003;352:146–150. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rosenmann H, Meiner Z, Kahana E, Aladjem Z, Friedman G, Ben-Yehuda A, Grenader T, Wertman E, Abramsky O. An association study of a polymorphism in the heparan sulfate proteoglycan gene (perlecan, HSPG2) and Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2004;128B:123–125. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kalus I, Salmen B, Viebahn C, von Figura K, Schmitz D, D’Hooge R, Dierks T. Differential involvement of the extracellular 6-O-endosulfatases Sulf1 and Sulf2 in brain development and neuronal and behavioural plasticity. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13:4505–4521. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00558.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nagamine S, Tamba M, Ishimine H, Araki K, Shiomi K, Okada T, Ohto T, Kunita S, Takahashi S, Wismans RG, van Kuppevelt TH, Masu M, Keino-Masu K. Organ-specific sulfation patterns of heparan sulfate generated by extracellular sulfatases Sulf1 and Sulf2 in mice. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:9579–9590. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.290262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kalus I, Rohn S, Puvirajesinghe TM, Guimond SE, Eyckerman-Kolln PJ, Ten Dam G, van Kuppevelt TH, Turnbull JE, Dierks T. Sulf1 and Sulf2 differentially modulate heparan sulfate proteoglycan sulfation during postnatal cerebellum development: Evidence for neuroprotective and neurite outgrowth promoting functions. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0139853. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.