Abstract

Importance:

Although 13–20% of American adolescents experience a depressive episode annually, no scalable primary care model for adolescent depression prevention is currently available.

Objective:

To study whether CATCH-IT (Competent Adulthood Transition with Cognitive Behavioral Humanistic and Interpersonal Training) reduces the hazard for depression in at-risk adolescents identified in primary care, as compared to a general health education attention control (HE).

Design:

The Promoting AdolescenT Health (PATH) study compares CATCH-IT and HE in a phase 3 single-blind multicenter randomized attention control trial. Participants were enrolled from 2012 to 2016 and assessed at 2, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months post-randomization.

Setting:

Primary care.

Participants:

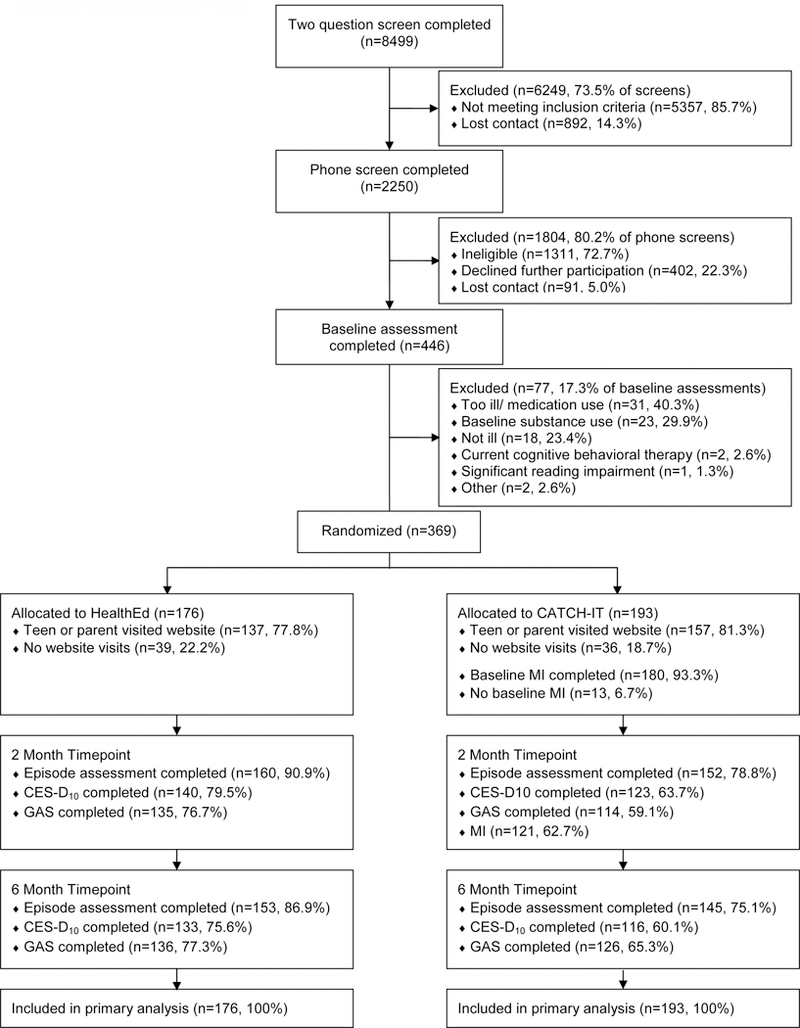

Eligible adolescents were 13–18 years with subsyndromal depression and/or history of depression and no current depression diagnosis or treatment. Of 2,250 adolescents screened for eligibility, 446 participants completed the baseline interview and 369 were randomized into CATCH-IT (n=193) and HE (n=176).

Interventions:

CATCH-IT is a 20-module (15 adolescent modules, 5 parent modules) online psychoeducation course that includes a parent program, supported by three motivational interviews.

Main Outcomes and Measures:

Time-to-event for depressive episode; depressive symptoms at 6 months.

Results:

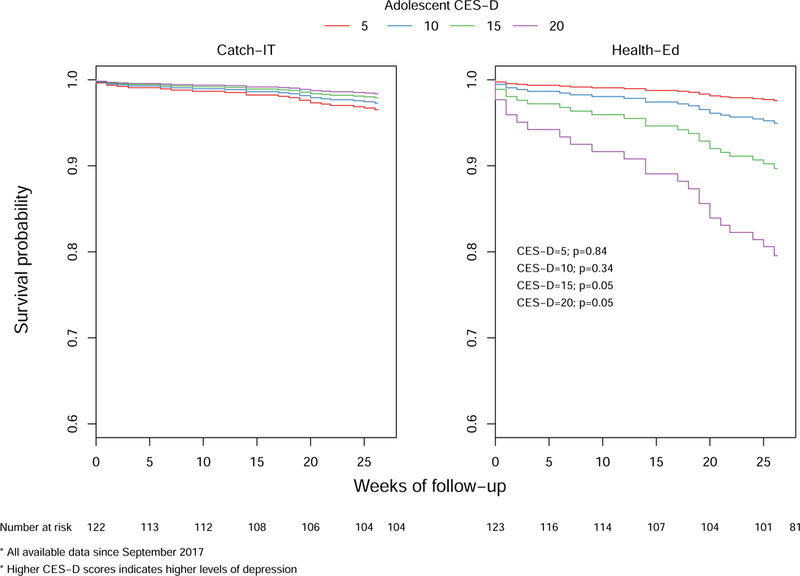

Mean age was 15.4 years, and 68% were female; 28% had both a past episode and subsyndromal depression; 12% had a past episode only, 59% had subsyndromal depression only, and 1% had borderline subsyndromal depression. The outcome of time-to-event favored CATCH-IT but was not significant with intention-to-treat analyses (N=369; unadjusted HR=0.59; 95% CI 0.27, 1.29; p=0.18; adjusted HR=0.53; 95% CI 0.23, 1.23, p=0.14). Adolescents with higher baseline CES-D10 scores showed a significantly stronger effect of CATCH-IT on time-to-event relative to those with lower baseline scores (p=0.04). For example, for a CES-D10 score of 15 (significant sub-syndromal depression), HR=0.20 (95% CI 0.05, 0.77), compared to CES-D10 of 5 (no sub-syndromal depression), HR=1.44 (95% CI, 0.41, 5.03). In both CATCH-IT and HE groups, depression symptoms declined and functional scores increased.

Conclusions and Relevance:

CATCH-IT may be better than HE for preventing depressive episodes for at-risk adolescents with sub-syndromal depression. CATCH-IT may be a scalable approach to prevent depressive episodes in adolescents in primary care.

Introduction

Approximately 13–20% of adolescents experience minor (mDE) or major (MDE) depressive episodes annually.1 These adolescents have a higher incidence of medical illness2 than those without mDE and MDE, and are at higher risk for suicide and recurrent depression.3–5 Effective depression prevention programs are essential.6

Promising findings for depression prevention programs are available. A Cochrane meta-analysis of prevention trials favored the intervention group over the control group with an overall risk difference for depressive disorders of −0.03, and for depression symptoms a standard mean difference of −0.21.7 A review noted a 22% risk reduction of depressive episodes for adolescents.7,8 Another meta-analysis involving 19 randomized preventive trials demonstrated significant reduction in depressive symptoms over two years among adolescents with higher symptom levels.9 Another review of traditional therapies augmented with computerized communications demonstrated small to moderate effect sizes for depressive symptoms.10 A systematic review of primary care-based interventions targeting depression identified 14 randomized clinical trials (RCTs); only one included adolescents, and average effect sizes were small.11 Targeted interventions that show success during trials may not be scalable due to practical issues such as cost, or prove ineffective in the broader community.12

The primary care-internet based intervention, Competent Adulthood Transition with Cognitive Behavioral Humanistic and Interpersonal Training (CATCH-IT) addresses the need for a scalable intervention.13–16 Internet-based interventions are accessible, cost-effective, private, and acceptable because they reduce stigma12. It is simple, consumer-friendly, and more easily scaled-up than more intensive, face-to-face interventions. A randomized clinical trial (RCT) in China found that CATCH-IT reduced depressive symptoms in adolescents over 12 months.17

We present a multi-site RCT testing the efficacy of CATCH-IT (Version 3) versus an internet-based Health Education (HE) attention control in primary care. We aimed to prevent the onset of depressive episodes and reduce symptoms in adolescents at intermediate to high risk for depression. Our primary hypothesis is that adolescents assigned to CATCH-IT relative to HE will have a lower hazard ratio for mDE or MDE at 6 months. We chose to evaluate group differences at 6 months to examine the potential of CATCH-IT as an immediate, medium-term response to depressive symptoms, given that follow-up intervals for such interventions in adolescents generally range from less than 6- to 12-months.12 We also hypothesize that adolescents in CATCH-IT will show improvement in depressed mood and functional status relative to HE.18

Methods

Study design and setting

We conducted a hybrid type I efficacy-implementation trial to test the effectiveness of CATCH-IT in a scalable setting and collected information regarding implementation.19 This two-site (Chicago and Boston) randomized trial compared CATCH-IT versus HE for preventing depressive episode onset in an intermediate to high-risk sample of adolescents in primary care. We defined risk status as teens’ (1) current elevated symptoms of depression (2) history of depressive episode, or (3) both. Depressive episodes are defined as a Depression Severity Rating (DSR) of 3 or more (exhibiting symptoms of sub-threshold MDE). At baseline, the participants’ average CES-D20 score was 16.9. Twelve percent of the sample enrolled with a past MDE only, 60% had current elevated symptoms only, and 28% had both a past MDE and elevated symptoms of depression. Participants were assessed at baseline and at 2 and 6 months post-enrollment. Dates of depressive episodes were recorded. Depressive episodes were diagnosed through the use of K-SADS interviews.

Institutional review board (IRB) approval was received from the central site (UIC) and local IRBs.20 This study followed the Consolidated Standard of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guidelines. The protocol, implementation process, and methods have been described in Supplement 1 and elsewhere.18 The study was conducted in clinics in Chicago, IL, northern Indiana, and Boston, MA.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Adolescents (aged 13–18) with elevated levels of depressive symptoms on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D)21 scale (scores 8–17 on the CES-D10, or scores≥16 on the CES-D20) at screening or at baseline, and/or a past history of depression or dysthymia,21–23 were eligible. Exclusion criteria were (a) current MDE diagnosis or treatment; (b) past Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT); (c) CES-D10 scores > 17;21 (d) schizophrenia, psychosis, or bipolar disorder; (e) serious medical condition (i.e, causing serious disability or dysfunction); (f) significant reading impairment or developmental disability; (g) imminent suicidal risk; and (h) current drug/alcohol abuse.24,27 Criteria were selected to avoid confounding factors in depression etiology or treatment, consistent with the use of CATCH-IT as a preventive intervention.

Participant recruitment and enrollment

Participants were recruited from 2012–2016 through: (1) a description of the study during doctor visits, (2) recruitment letters, and (3) posted flyers. Adolescents were screened for risk in-person or by phone. After parental consent, adolescents participated in an eligibility assessment by phone. The parent and adolescent attended an enrollment assessment at their primary care office, when written informed consent from parents and assent from adolescents were obtained, and assessments were administered to confirm eligibility.25

Randomization

Participants were assigned randomly to CATCH-IT or HE (1:1 allocation) using a computer generated sequence blocked by site and time of entry (random blocks of size 4 and 6), stratified by risk severity (based on CES-D score, prior MDE or dysthymia), gender and age (13–14 or 15–18).26,27

Blinding

Randomization was concealed from investigators, clinicians, patients, and families until the baseline consent, enrollment, data collection, and assessment were completed. Study participants could not be blinded to their arm assignment. The provider was also not blinded, as s/he was expected to conduct three motivational interviews (MI) for CATCH-IT participants. Assessors remained blinded throughout the study. Principal investigators (BVV and TG) were blinded to between-group comparisons and group descriptive data until all 6-month follow-up data were collected.

Retention

Challenges related to ongoing study participation were addressed by research staff. Approaches used to maintain contact were birthday cards and regular contact updates.

Outcomes

Occurrence of first depressive episode was determined by the DSR. We considered a score indicating at least sub-threshold major depression (a DSR of ≥3) to be a depressive episode. To test for robustness of findings, we also examined data using a DSR cut-off of ≥4, indicating probable MDE, and DSR=5, indicating the presence of MDE.28 Symptom outcomes include the CES-D1021 and Global Assessment Scale (GAS) scores.

CATCH-IT intervention

CATCH-IT includes an internet component (15 adolescent modules, based primarily on the Coping with Depression Adolescent Course,29 behavioral activation,30 and interpersonal psychotherapy),31 a brief motivational component (three physician MIs at 0, 2, and 12 months), and 1–3 staff coaching phone calls either at 1 month [Chicago] or at 2 and 4 weeks [Boston], and 18 months. There were also up to three “check-in” calls during weeks 1–3 to facilitate website use. The parent internet intervention component (5 modules) is based on an adaptation of the Preventive Intervention Project.32 A description of the intervention has been published.18,33

HE intervention

HE is an attention control internet site (14 modules) providing instruction on general health topics. The 14th module discusses mood and mental health treatment, and also addresses mental disorder stigma.14,34 Up to three “check-in” calls (weeks 1 to 3) were offered to ensure website access. The caregiver internet program (4 modules) is similar.

Intervention shared elements

Both interventions were consistent with GLAD-PC guidelines, including: (1) training clinicians in depression identification, diagnosis, and treatment; (2) establishing referral relationships; (3) screening; (4) using a formal tool to determine depression risk; (5) assessing depression; (6) interviewing caregivers and adolescents; (7) educating caregivers and adolescents on treatment; (8) establishing treatment plans; and (9) establishing safety plans.35 These steps are closely related to the Chronic Care Model.36 Rates of episodes were extremely low for this high-risk sample. When episodes were identified, adolescents were referred for treatment, and caregivers and pediatricians were notified.

Instruments

Instruments have been described previously.18 The two-question screener was based on the Patient Health Questionnaire-Adolescent (PHQ).37,38 The Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders Scale (K-SADS)39,40 is a semi-structured interview assessing current and lifetime psychiatric diagnoses in participants under age 18, administered to parents and adolescents.39,41 DSRs are obtained from the Kiddie Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation (K-LIFE)41 for each week of the follow-up interval, and GAS ratings were assigned at each assessment. For both the K-SADS and the K-LIFE, precipitating events were reviewed, and episodes secondary to medical concerns were indicated, if they occurred. The CES-D10 measures the frequency of 10 depressive symptoms over the past week, using a four-point scale; it was completed at baseline, 2, and 6 months.21 Demographic information was collected at baseline, including race and ethnicity using categories defined by the study team. Fidelity and exposure to the intervention were based on module completion, and completion and rating of the MIs, with two trained raters using the Motivational Interview Treatment Integrity 4 (MITI 4.2.1) coding manual42, and number of characters typed into the CATCH-IT website.

Sample size

We required 200 participants per intervention condition to achieve 80% power based on a conservative application of our pilot study findings.40 These calculations assumed that in the control group 72% are free from depression after one year follow-up, and the second year continues to follow the same exponential rate for controls; for intervention, the hazard is a constant ratio of 0.62, and an attrition rate of 7% for each of the first four quarters and 2% for each of the second four quarters (Supplement 1).

Statistical analysis

We tested for differences between group medians in website engagement using Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. We estimated incidence rates by calculating the number of depressive episodes per 10,000 person-weeks of follow-up. Kaplan-Meier curves were used to estimate the time to first episode distribution for each intervention under six different treatment allocations (eTable 1). Treatment allocations were developed based on existent literature with regard to “threshold” effects of adherence as an a priori analytic strategy. The thresholds were applied in the same manner with both interventions with similar numbers of persons identified in each arm. Cox proportional hazard regression was used to estimate the hazard ratio (HR) comparing CATCH-IT to HE. We present adjusted (sex, ethnicity [Hispanic/non-Hispanic], race [white/non-white], baseline age, site, baseline CES-D10 score) and unadjusted hazard ratios. The assumption of proportional hazards was checked by testing the independence between the Schoenfeld residuals and time.43 We examined moderating effects of baseline adolescent CES-D10 score as a continuous variable, exhibited across a range of possible CES-D10 values, by including interaction terms in the Cox models. We used linear mixed effect growth models with random intercepts and slopes to examine differences between group change over time in CES-D10 and GAS. Analyses were adjusted for the covariates listed above. We used propensity scores to account for differences between treatment groups in the Per Protocol analysis (N≥2 modules completed) that could otherwise confound treatment effect estimates, controlling for: site, age, sex, ethnicity, race, mother’s education, parents’ marital status, number of siblings, firstborn child, times moved, current GAS score, most severe past GAS score, highest past GAS score, and baseline CES-D10. Analyses were conducted using R, version 3.3.1 (cran.r-project.org), SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), and Mplus version 8 (www.statmodel.com).44

Missing Data

The percent of participants missing each K-SADS or CES-D10 assessment was calculated. We used a logistic regression model to determine whether those missing from follow-up differed from those who were not (eTables 8b–e). We also used multiple imputation to assess the potential for differential follow-up by intervention condition. We constructed 50 datasets for each site and intervention condition with fully saturated specification by condition interacting with the following variables: all CES-D10 and GAS values (0, 2, 6 months), screening CES-D10, baseline age, sex, ethnicity, race, and maternal education. These were combined into 50 complete imputed datasets and analyzed separately using the growth models described above; results were pooled.

Results

Implementation:

We implemented the study in 8 health systems from 31 practices in a defined population of >41,000 adolescents. There were 8,499 adolescents screened, 2,250 phone assessments, 446 enrolled, and 369 randomized. The two groups consisted of CATCH-IT (n=193) and HE (n=176) (Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Consort Diagram

Sample:

Participants were 13–18 years (Mean=15.4, SD=1.5), 68% female, with history of depression and/or current sub-syndromal depressive symptoms. Participants were diverse in self-reported race and ethnicity: 21% Hispanic, 26% Black/non-Hispanic, 43% White/non-Hispanic, 4% Asian, and 6% multiracial/other. Sixty-one percent had married parents, and 53% of the fathers were college graduates. Adolescents were moderately depressed (CES-D10=9.4, SD=4.6), moderately impaired (GAS= 78.1, SD=9.4), 62% with a prior DSR ≥3, and 40% with a prior DSR ≥4 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics at Baseline

| All (N=369) | CATCH-IT (N=193) | Health Ed (N=176) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean (SD) or N (%) | N | Mean (SD) or N (%) | N | Mean (SD) or N (%) | |

| Age, years | 369 | 15.4 (1.5) | 193 | 15.4 (1.5) | 176 | 15.5 (1.5) |

| Sex | 369 | 193 | 176 | |||

| Female | 251 (68%) | 134 (69%) | 117 (66%) | |||

| Male | 118 (32%) | 59 (31%) | 59 (34%) | |||

| Ethnicity | 369 | 193 | 176 | |||

| Hispanic | 77 (21%) | 41 (21%) | 36 (20%) | |||

| Not Hispanica | 292 (79%) | 152 (79%) | 140 (80%) | |||

| Race | 369 | 193 | 176 | |||

| White | 201 (54%) | 107 (55%) | 94 (53%) | |||

| Not whiteb | 168 (46%) | 86 (45%) | 82 (47%) | |||

| Mother’s education | 359 | 188 | 171 | |||

| Some HS | 12 (3%) | 5 (3%) | 7 (4%) | |||

| HS graduate/GED | 45 (13%) | 20 (11%) | 25 (15%) | |||

| Some college | 87 (24%) | 44 (23%) | 43 (25%) | |||

| College graduate | 215 (60%) | 119 (63%) | 96 (56%) | |||

| Father’s education | 336 | 177 | 159 | |||

| Some HS | 26 (8%) | 12 (7%) | 14 (9%) | |||

| HS graduate/GED | 76 (23%) | 36 (20%) | 40 (25%) | |||

| Some college | 55 (16%) | 37 (21%) | 18 (11%) | |||

| College graduate | 179 (53%) | 92 (52%) | 87 (55%) | |||

| K-SADS | ||||||

| GAS, currentc | 367 | 78.1 (9.4) | 193 | 78.3 (9.3) | 174 | 78.0 (9.6) |

| GAS, most severe pastc | 359 | 67.5 (10.9) | 189 | 68.1 (10.3) | 170 | 67.0 (11.5) |

| GAS, highest pastc | 360 | 82.2 (8.5) | 190 | 82.3 (8.4) | 170 | 82.1 (8.5) |

| DSR, most severed | 364 | 3.1 (1.4) | 189 | 3.1 (1.4) | 175 | 3.2 (1.4) |

| ≥3+ | 226 (62%) | 113 (60%) | 113 (65%) | |||

| ≥4 | 144 (40%) | 75 (40%) | 69 (39%) | |||

| DSR, currentd | 365 | 1.8 (0.9) | 190 | 1.7 (0.9) | 175 | 1.8 (0.9) |

| CES-D20e | 362 | 16.9 (8.7) | 190 | 17.3 (8.7) | 172 | 16.5 (8.8) |

| CES-D10f | 362 | 9.4 (4.6) | 190 | 9.5 (4.5) | 172 | 9.4 (4.6) |

| SCARED total scoreg | 312 | 25.3 (12.3) | 171 | 25.5 (12.7) | 141 | 25.2 (11.9) |

Participants with missing ethnicity data were coded as not Hispanic (N=6).

Participants with missing race data were coded as not white (N=20; most identified as Hispanic).

Possible range: 1–100. A higher score indicates higher functioning.

Possible range: 1–6. A higher score indicates more severe depression.

Possible range: 0–60. A higher score indicates more severe depression.

Possible range: 0–30. A higher score indicates more severe depression.

Possible range: 0–82. A higher score indicates greater anxiety.

Fidelity and Intervention Exposure:

Intervention use was monitored and recorded. The number of motivational interviews completed was recorded for CATCH-IT participants. Table 2 shows that CATCH-IT adolescents and parents spent more time, but CATCH-IT adolescents completed fewer modules than HE adolescents (median 1.0 versus 4.0 modules, p=0.003). Both study arms received a sizable dose of the interventions, with the combined (parent + adolescent) module completion greater for HE (median=4.0 versus 8.0 modules, p<0.001). CATCH-IT adolescents and parents typed an average of 3,071 (SD=4,572) and 716 (SD=977) characters respectively (Table 2). Greater than 73% of MIs and phone calls were completed. Mean interview length was 7.7 minutes (SD=4.0), technical global rating was 3.0 on a 1–5 scale (SD=0.5), and relational global rating was 2.9 (SD=0.6) (eTable 2).

Table 2.

Fidelity Assessment of Internet Component

| CATCH-IT | Health Ed | Difference CATCH-IT - Health Ed | CATCH-IT | Health Ed | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Website use | Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) | Mean | (95% CI) | Median | (IQR) | Median | (IQR) | pa |

| Adolescents | N=193 | N=176 | |||||||||

| Modules completed | 3.4 | (4.7) | 6.8 | (6.5) | −3.4 | (−4.5, −2.2) | 1.0 | (4.0) | 4.0 | (14.0) | 0.003 |

| Total minutes on site | 100.2 | (143.1) | 22.8 | (31.0) | 77.4 | (55.7, 99.0) | 39.6 | (149.2) | 8.4 | (35.1) | <0.001 |

| Days visited site | 3.7 | (4.5) | 1.4 | (1.6) | 2.3 | (1.6, 3.0) | 2.0 | (4.0) | 1.0 | (2.0) | <0.001 |

| Total characters typed | 3071 | (4572) | -- | -- | -- | -- | 923 | (4469) | -- | -- | -- |

| Adolescents +Parents | |||||||||||

| Modules completed | 5.3 | (5.8) | 8.8 | (7.3) | −3.5 | (−4.8, −2.1) | 4.0 | (8.0) | 8.0 | (17.0) | <0.001 |

| Total minutes on site | 130.6 | (157.9) | 30.6 | (35.6) | 100.0 | (76.1, 124.0) | 75.8 | (192.2) | 18.9 | (40.8) | <0.001 |

| Days visited site | 5.2 | (5.2) | 2.2 | (2.2) | 2.9 | (2.1, 3.8) | 4.0 | (6.0) | 2.0 | (2.0) | <0.001 |

| Total characters typed | 3713 | (4932) | -- | -- | -- | -- | 1899 | (5792) | -- | -- | -- |

| Parents | N=165 | N=157 | |||||||||

| Modules completed | 2.1 | (2.0) | 2.2 | (1.9) | −0.1 | (−0.6, 0.3) | 2.0 | (4.0) | 4.0 | (4.0) | 0.80 |

| Total minutes on site | 32.6 | (37.3) | 8.6 | (10.0) | 24.0 | (17.9, 30.0) | 22.4 | (51.9) | 5.6 | (14.9) | <0.001 |

| Days visited site | 1.6 | (1.6) | 0.9 | (1.1) | 0.6 | (0.3, 0.9) | 1.0 | (2.0) | 1.0 | (1.0) | <0.001 |

| Total characters typed | 716 | (977) | -- | -- | -- | -- | 101 | (1205) | -- | -- | -- |

SD: standard deviation; CI: confidence interval; IQR: interquartile range.

Medians compared using Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

Outcomes:

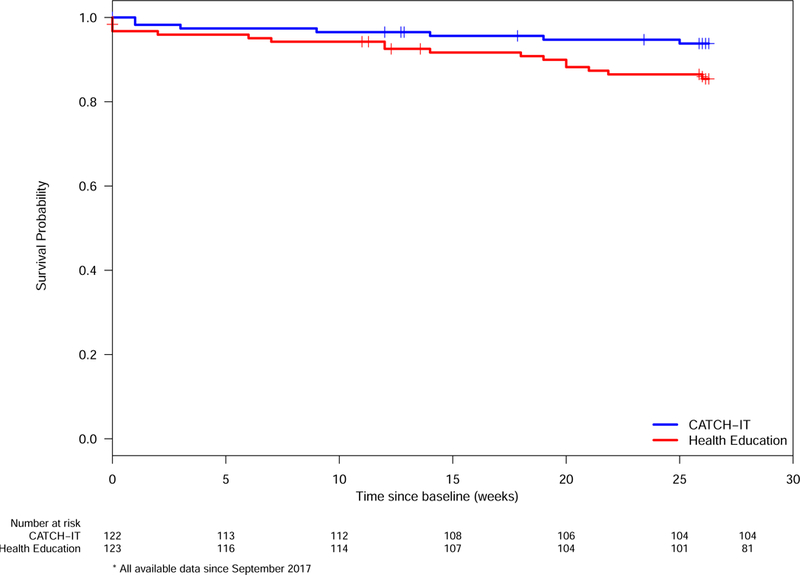

For the primary outcome of time to depressive episode (DSR ≥3) using ITT analyses (N=369), unadjusted HR was 0.59 (95% CI 0.27, 1.29, p=0.18), and adjusted HR was 0.53 (95% CI 0.23, 1.23, p=0.14). Proportional hazards assumption was met (p=0.89). For per protocol analysis (N≥2 modules completed on either arm, N=245) (Figure 2), unadjusted HR was 0.41 (95% CI 0.17, 0.99, p=0.047) and adjusted HR was 0.44 (95% CI 0.18, 1.08, p=0.07). After adjusting for potential confounders using propensity scores, HR=0.52 (95% CI 0.19, 1.42, p=0.20). Additional analyses are shown in eTable 3, and incidence rates in eTable 4. We calculated the number needed to treat (NNT) to indicate the number of adolescents who would need to receive the intervention to prevent 1 additional onset of depressive disorder and found an NNT of 36 for the main effect of CATCH-IT. Adolescents with higher baseline CES-D10 scores showed a significantly stronger effect of CATCH-IT on time to event relative to those with lower baseline scores (p=0.04) (Figure 3, eTable 5). For example, for a CES-D10 score of 15, HR=0.20 (95% CI 0.05, 0.77), compared to CES-D10 of 5, HR=1.43 (95% CI, 0.41, 5.03). Gender, ethnicity, race, and age did not predict outcome or interact significantly with the interventions and outcomes. Both CATCH-IT and HE demonstrated reduced depressed mood and improved functional status, with no statistically significant differences at 6 months (eTables 6, 7).

Figure 2:

Time to First Depressive Episode for Those Completing 2+ Modules (Per Protocol 2 Analysis)

Figure 3:

First Depressive Episode Survival Analysis by Adolescent Baseline CES-D Scores

Missing data:

At least 1 follow-up K-SADS was completed for 85% of the sample, at least 1 follow-up CES-D10 was completed for 80% of the sample, and at least 1 follow-up GAS assessment was completed for 81% of the sample. Drop out between CATCH-IT and HE was different at two and six months for both K-SADS and CES-D10 (eTable 8a). At 6 months, K-SADS data were missing for 25% of CATCH-IT and 13% of HE (p=0.004), and CES-D10 was missing for 40% and 24% (p=0.002). Significant predictors of missing K-SADS at 6 months were randomization to CATCH-IT (OR=2.62, p=0.002), living in Chicago (OR for Boston vs Chicago=0.20, p<0.001), age (OR=1.23, p=0.03), and maternal education (OR for HS graduate or less vs college graduate=2.99, p=0.006), eTable 8c. Having a past episode or high CES-D10 at baseline was not associated with missing follow-up.

Discussion

Overall, we observed a non-significant decrease in depressive disorders at six months in CATCH-IT as compared to HE. Adolescents and parents devoted substantial time to both interventions, and both conditions experienced decreased depressive symptoms and improved functional status. However, higher risk adolescents demonstrated greater benefit from CATCH-IT, achieving as much as 80% risk reduction with a CES-D10 score >15, but those without symptoms showed no such benefit. While regression to the mean is a possible explanation for the moderating effect of high CES-D on CATCH-IT, other studies have found that preventive effects for depression interventions are stronger for indicated versus universal samples.45 Moreover, the same effect did not emerge for the HE condition (that is, higher CES-D scores did not moderate the effect of the HE condition), suggesting regression to the mean may not explain the group difference we found. For the 66% of adolescent/parent pairs who completed at least 2 modules (63% CATCH-IT; 70% HE), the unadjusted analysis showed CATCH-IT reduced the risk of mDE and MDE by 59%, but this was not significant after adjustment for demographic factors or after analyses incorporating propensity scoring.

To our knowledge, this is the first clinical trial in adolescents to evaluate whether depressive episodes can be prevented in primary care settings.11 Our finding that the risk of depressive episodes may be reduced for adolescents with sub-syndromal depression is consistent with our earlier phase two clinical trial, which only included adolescents with sub-syndromal depression.46 Results were not significant in the ITT main effect analysis, but this may be the result of heterogeneity of treatment effect whereby CATCH-IT is favored for those with sub-syndromal depression, but not for those with prior depressive episode alone. Perhaps CATCH-IT “bored” or frustrated adolescents without current symptoms, or conversely, elicited increased surveillance of symptoms or stimulated memories of prior episodes.47–49 Alternatively, adolescents who are not symptomatic may be less motivated to complete CATCH-IT, the more self-directed intervention, and may actually prefer HE, which did not require substantial effort, perhaps even gaining a sense of self-efficacy.34,47,49–51 Also, despite spending substantial time engaged with this intervention, the low number of modules completed may have attenuated impact. Additionally, the borderline significant findings favoring CATCH-IT with the completion of 2 modules (eTable3) suggest that there may also be a threshold effect whereby sufficient numbers of modules may need to be completed for CATCH-IT be more efficacious than HE.

Depression prevention programs have shown mixed results.12 The only other primary-care trial with adolescents demonstrated improvements in explanatory style but not depressed mood.52 Our findings showing that increased participation may predict better outcomes are consistent with prior reports.52,53 The observed risk reduction across multiple outcomes (DSR ≥3, ≥4 and =5, eTable3), even if not statistically significant, is comparable to other trials.7,8,28 While most internet interventions demonstrate favorable changes in depressed mood, our study did not demonstrate between group differences for mood or functional status.10 However, this is similar to the phase 2 clinical trial of CATCH-IT, which demonstrated lower cumulative prevalence of depressive episodes, but not between group differences in depressed mood.38 It is possible the extensive human contact within this trial had an ameliorating effect on mood and strengthened functional status, effectively blurring between group results. A clinical trial of CATCH-IT in Hong Kong that only used self-report instruments demonstrated a significant between group effect (effect size=0.36) for depressed mood at 12 months.17

This study has a robust prevention design implemented in a population-based model in primary care.54,55 The implementation of our study at two sites and eight health systems has rarely been accomplished in studies of child psychiatric conditions.20 This study fits Curran’s model19 of hybrid efficacy and implementation studies and substantially enhances generalizability. The attention control condition, which included GLAD-PC and Chronic Care Model elements, no doubt reduced between group differences.23,36 However, given the need for ethical care of adolescents at risk for depressive episodes, a “no intervention” or “wait list control” condition is not possible.55,56

Limitations:

There are several limitations of this study, including the relatively low adherence rate of teens and parents. Module completion for CATCH-IT was consistent with pilot findings. A review of internet-based mental health interventions for youth revealed completion ranged from 24–85%, and it was not necessary to complete the entire intervention for positive benefits to emerge.12 In addition, module completion does not correlate with time spent, as the HE modules are significantly shorter than CATCH-IT; overall, CATCH-IT participants spent more time using the intervention. Nevertheless, future research should examine why adolescents did not complete the interventions, and explore strategies for boosting adherence. Also, our incidence rate for depressive disorders was surprisingly low, thus increasing the number of participants needed to have adequate power to detect group differences. We do not know for certain whether intervention effects can be attributed to the internet-based modules or to the MI, although results from our pilot study suggest that adolescents who did not get MIs still evidenced reduced symptoms of depression at follow-up. Other limitations include the findings of differential attrition, which were adjusted analytically, and the fact that researchers enrolled only 92% of the target sample.

Conclusions:

Our long-term goal for the CATCH-IT intervention is to provide a first-line program for PCPs to offer as part of the GLAD-PC guidelines, to support adolescents while the need for further intervention can be evaluated. We continue to examine moderators that may explain who responds best to this approach. Future directions include the development of versions for personal devices (e.g., tablets, mobile phones), and a version individualized for sexual- and gender-minority teens.

A scalable, population-based approach to preventing depression in adolescents in primary care may be efficacious for adolescents with sub-syndromal depression, but not for those with a prior episode alone.

Supplementary Material

Key Points:

Questions:

Does an internet-based depression prevention program (CATCH-IT) reduce the hazard for depression in at-risk adolescents relative to health education attention control (HE)?

Findings:

In this randomized clinical trial of adolescents with sub-syndromal depression or history of depression randomized to receive internet-based behavioral humanistic interpersonal training or an internet-based general health education control, those who received the intervention did not evidence fewer episodes of depression in the full Intention to Treat (ITT) sample (adjusted HR=0.53), but adolescents with sub-syndromal depression may have experienced fewer depressive episodes (HR=0.20).

Meaning:

CATCH-IT may be better than HE for preventing depression in adolescents with sub-syndromal depression.

Acknowledgements:

Research reported in this article was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01MH090035. The NIMH/NIH played no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data, preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Trial Registration: Clinical Trial Registry (clinicaltrials.gov): NCT01893749

Footnotes

Disclosures: Benjamin W. Van Voorhees has served as a consultant to Prevail Health Solutions, Inc., Mevident Inc., San Francisco and Social Kinetics, Palo Alto, CA, and the Hong Kong University to develop Internet-based interventions.

Ethical bodies that approved this study include: University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) Institutional Review Board (IRB) the IRB of Record, Wellesley College IRB, Advocate Health Care IRB, Northshore University Health Systems IRB, Northwestern IRB and Access Healthcare IRB. Methods developed under Robert Wood Johnson (Project Curb “Chicago Urban Resiliency Building”: Reducing Life Course Disparities in Depression Outcomes in Urban Youth Through Early Preventive Intervention) supported and informed the implementation process.

References:

- 1.Medicine NRCaIo. Preventing Mental, Emotional, and Behavioral Disorders Among Young People: Progress and Possibilities Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khalil BA, Gillham JC, Foresythe L, et al. Successful management of short gut due to vanishing gastroschisis - case report and review of the literature. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2010;92(5):e10–e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Georgiades K, Lewinsohn PM, Monroe SM, Seeley JR. Major depressive disorder in adolescence: the role of subthreshold symptoms. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2006;45(8):936–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klein DN, Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR, Olino TM. Psychopathology in the adolescent and young adult offspring of a community sample of mothers and fathers with major depression. Psychol Med 2005;35(3):353–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Klein DN, Seeley JR. Natural course of adolescent major depressive disorder: I. Continuity into young adulthood. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1999;38(1):56–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garber J Depression in children and adolescents: linking risk research and prevention. Am J Prev Med 2006;31(6 Suppl 1):S104–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Merry S, McDowell H, Hetrick S, Bir J, Muller N. Psychological and/or educational interventions for the prevention of depression in children and adolescents. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews 2004(1):CD003380. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), third-wave CBT and interpersonal therapy (IPT) based interventions for preventing depression in children and adolescents 2016. Accessed Aug 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Brown CH, Brincks A, Huang S, et al. Two-Year Impact of Prevention Programs on Adolescent Depression: an Integrative Data Analysis Approach. Prevention science : the official journal of the Society for Prevention Research 2018;19(Suppl 1):74–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abuwalla Z, Clark MD, Burke B, et al. Long-term telemental health prevention interventions for youth: A rapid review. Internet Interventions 2018;11:20–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conejo-Cerón S, Moreno-Peral P, Rodríguez-Morejón A, et al. Effectiveness of Psychological and Educational Interventions to Prevent Depression in Primary Care: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ann of Fam Med 2017;15(3):262–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Merry S Preventing depression in adolescents: Time for a new approach? JAMA Pediatrics 2013;167(11):994–995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gagne RMBL, Wager WW. Principles of Instructional Design Fort Worth, TX: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publishers; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Landback J, Prochaska M, Ellis J, et al. From prototype to product: development of a primary care/internet based depression prevention intervention for adolescents (CATCH-IT). Community Ment Health J 2009;45(5):349–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Voorhees BW, Watson N, Bridges J. Development and pilot study of a marketing strategy for primary care/internet based depression prevention intervention for adolescents (CATCH-IT). Journal of Clinical Psychiatry Primary Care Companion in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Van Voorhees BW, Ellis JM, Gollan JK, et al. Development and Process Evaluation of a Primary Care Internet-Based Intervention to Prevent Depression in Emerging Adults. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2007;9(5):346–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ip P, Chim D, Chan KL, et al. Effectiveness of a culturally attuned Internet-based depression prevention program for Chinese adolescents: A randomized controlled trial. Depress Anxiety 2016;33(12):1123–1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gladstone TG, Marko-Holguin M, Rothberg P, et al. An internet-based adolescent depression preventive intervention: study protocol for a randomized control trial. Trials 2015;16:203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B, Pyne JM, Stetler C. Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Med Care 2012;50(3):217–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mahoney N, Gladstone T, DeFrino D, et al. Prevention of Adolescent Depression in Primary Care: Barriers and Relational Work Solutions. California Journal of Health Promotion 2017;15(2):1–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Radloff LS. The use of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale in adolescents and young adults. J Youth Adolesc 1991;20(2):149–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lewinsohn PM, Clarke GN, Seeley JR, Rohde P. Major depression in community adolescents: age at onset, episode duration, and time to recurrence. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 1994;33(6):809–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Voorhees BW, Paunesku D, Gollan J, Kuwabara S, Reinecke M, Basu A. Predicting future risk of depressive episode in adolescents: the Chicago Adolescent Depression Risk Assessment (CADRA). Ann Fam Med 2008;6(6):503–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knight JR, Shrier LA, Bravender TD, Farrell M, Vander Bilt J, Shaffer HJ. A new brief screen for adolescent substance abuse. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1999;153(6):591–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van Voorhees BW, Watson N, Bridges JF, et al. Development and Pilot Study of a Marketing Strategy for Primary Care/Internet-Based Depression Prevention Intervention for Adolescents (The CATCH-IT Intervention). Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2010;12(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pastore DR, Juszczak L, Fisher MM, Friedman SB. School-based health center utilization: a survey of users and nonusers. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1998;152(8):763–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Piantadosi S Clinical trials: a methodologic perspective Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garber J, Clarke GN, Weersing VR, et al. Prevention of depression in at-risk adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2009;301(21):2215–2224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clarke GN. The coping wIth stress course adolescent: workbook Portland, OR: Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jacobson NSMC, Dimdjian S. Behavioral Activation Treatment for Depression: Returning to Contextual Roots. Clin Psychol 2001;8(3):255–270. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stuart SRM. Interpersonal Psychotherapy A Clinicians Guide New York, New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beardslee WR, Gladstone TR, Wright EJ, Cooper AB. A family-based approach to the prevention of depressive symptoms in children at risk: evidence of parental and child change. Pediatrics 2003;112(2):e119–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van Voorhees BW, Gladstone T, Cordel S, et al. Development of a technology-based behavioral vaccine to prevent adolescent depression: A health system integration model. Internet Interventions 2015;2(3):303–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Voorhees BW, Fogel J, Houston TK, Cooper LA, Wang NY, Ford DE. Beliefs and attitudes associated with the intention to not accept the diagnosis of depression among young adults. Annals of Family Medicine 2005;3(1):38–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zuckerbrot RACA, Jensen PS, Stein R, Laraque D, GLAD-PC STEERING GROUP. Guidelines for Adolescent Depression in Primary Care (GLAD-PC): Part I. Practice Preparation, Identification, Assessment, and Initial Management. Pediatrics 2018;in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Van Voorhees BW, Walters AE, Prochaska M, Quinn MT. Reducing Health Disparities in Depressive Disorders Outcomes between Non-Hispanic Whites and Ethnic Minorities: A Call for Pragmatic Strategies over the Life Course. Med Care Res Rev 2007;64((5 Suppl)):157S–194S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johnson JG, Harris ES, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The patient health questionnaire for adolescents: Validation of an instrument for the assessment of mental disorders among adolescent primary care patients. J of Adolesc Health 2002;30(3):196–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van Voorhees BW, Fogel J, Reinecke MA, et al. Randomized Clinical Trial of an Internet-Based Depression Prevention Program for Adolescents (Project CATCH-IT) in Primary Care: 12-Week Outcomes. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2009;30(1):23–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, et al. Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children-present and lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997;36(7):980–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent DA, Ryan ND, Rao U. K-Sads-Pl. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2000;39(10):1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Keller MB, Lavori PW, Friedman B, et al. The Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation: a comprehensive method for assessing outcome in prospective longitudinal studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1987;44(6):540–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moyers TB, Rowell LN, Manuel JK, Ernst D, Houck JM. The Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity Code (MITI 4): Rationale, Preliminary Reliability and Validity. J Subst Abuse Treat 2016;65:36–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grambsch PM, Therneau TM. Proportional Hazards tests and diagnostics based on weighted residuals. Biometrika 1994;81:515–526. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Muthén LK. Mplus: Statistical Analysis with Latent Variables (Version 4.21)[Computer software 2007.

- 45.Horowitz JL, Garber J, Ciesla JA, Young JF, Mufson L. Prevention of depressive symptoms in adolescents: a randomized trial of cognitive-behavioral and interpersonal prevention programs. J Consult Clin Psychol 2007;75(5):693–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saulsberry A, Marko-Holguin M, Blomeke K, et al. Randomized Clinical Trial of a Primary Care Internet-based Intervention to Prevent Adolescent Depression: One-year Outcomes. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2013;22(2):106–117. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Linares IMP. Early interventions for the prevention of PTSD in adults: a systematic literature review. Archives of Clinical Psychiatry (São Paulo) 2017;44(1). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Van Voorhees B, Ellis J, Gollan J, Bell C, Stuart S, Fogel J, et al. Development and Process Evaluation of a Primary Care Internet-Based Intervention to Prevent Depression in Young Adults. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2007;9(5):346–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Iloabachie C, Wells C, Goodwin B, Baldwin M, Vanderplough-Booth K, Gladstone T, Murray M, Fogel J, Van Voorhees BW. Adolescent and Parent Experiences with a Primary Care/Internet Based Depression Prevention Intervention. General Hospital Psychiatry 2011;33(6):543–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Van Voorhees BW, Ellis J, Stuart S, Fogel J, Ford DE. Pilot study of a primary care internet-based depression prevention intervention for late adolescents. The Canadian Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Review 2005;14(2):40–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Resnicow K, Davis RE, Zhang G, et al. Tailoring a fruit and vegetable intervention on novel motivational constructs: results of a randomized study. Ann Behav Med 2008;35(2):159–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gillham JE, Hamilton J, Freres DR, Patton K, Gallop R. Preventing depression among early adolescents in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled study of the Penn Resiliency Program. J Abnorm Child Psychol 2006;34(2):203–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Van Voorhees BW, Mahoney N, Mazo R, et al. Internet-based depression prevention over the life course: A call for behavioral vaccines. Psychiatric Clin North A 2011;34(1):167–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bauer NS, Webster-Stratton C. Prevention of behavioral disorders in primary care. Current opinion in pediatrics 2006;18(6):654–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bansa M, Brown D, DeFrino D, et al. A Little Effort Can Withstand the Hardship: Fielding an Internet-Based Intervention to Prevent Depression among Urban Racial/Ethnic Minority Adolescents in a Primary Care Setting. Journal of the National Medical Association 2017. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 56.DeFrino DT, Marko-Holguin M, Cordel S, Anker L, Bansa M, Van Voorhees B. “Why Should I Tell My Business?”: An Emerging Theory of Coping and Disclosure in Teens. Res Theory Nurs Pract 2016;30(2):124–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.