Abstract

Importance.

Sexual harassment and sexual assault are prevalent experiences among women. However, their relation to health indices is less well understood.

Objective.

To investigate the relation of a history of sexual harassment and sexual assault to blood pressure, mood, anxiety, and sleep among midlife women.

Design.

Women completed physical measurements (blood pressure, height, weight), medical history, and questionnaire psychosocial assessments (workplace sexual harassment, sexual assault, depression, anxiety, sleep).

Setting.

Participants were recruited from the community.

Participants.

304 nonsmoking women, ages 40–60, free of clinical cardiovascular disease

Exposures.

Sexual harassment and sexual assault.

Main Outcomes and Measures.

Blood pressure, depressive symptoms, anxiety, sleep

Results.

Among these midlife women, 19% reported a history of workplace sexual harassment, and 22% reported a history of sexual assault. Sexual harassment was related to significantly greater odds of stage 1 or 2 hypertension among women not taking antihypertensives [odds ratio(95% confidence interval)=2.36 (1.10–5.06), p=.03] as well as clinically poor sleep [odds ratio(95% confidence interval)=1.89 (1.05–3.42), p=.03], adjusting for covariates; sexual assault related to significantly greater odds of clinically elevated depressive symptoms [odds ratio(95% confidence interval)= 2.86 (1.42–5.77), p=.003, multivariable], clinically relevant anxiety [odds ratio(95% confidence interval) =2.26(1.26–4.06), p=.006], and clinically poor sleep [odds ratio(95% confidence interval)=2.15 (1.23–3.77), p=.007], adjusting for covariates.

Conclusions and Relevance.

Sexual harassment and sexual assault are prevalent experiences among midlife women. Sexual harassment was associated with higher blood pressure and poorer sleep. Sexual assault was associated with poorer mental health and sleep. Efforts to improve women’s health should target sexual harassment and assault prevention.

Introduction

Sexual harassment and sexual assault are common experiences among women. In the United States (US), an estimated 40–75% of women have experienced workplace sexual harassment,1 and over 1 in 3 women (36%) have experienced sexual assault.2 With recent popular movements (e.g., MeToo, Time’s Up), there is rising public awareness of sexual harassment and assault and their implications for women’s health.

Both sexual harassment and sexual assault have been linked to poorer self-reported physical and mental health outcomes.3–8 While these studies suggest that harassment and assault are associated with adverse outcomes broadly, the impact of these findings is limited by several issues. Survey studies, particularly of sexual harassment, largely assess physical health via self-report. These reports can be biased by mood, memory, and reporting of physical symptoms;9 and by awareness of health conditions, which can vary by socioeconomic status, healthcare access, and health literacy.10 Another limitation is incomplete consideration of critical confounding factors, such as socioeconomic position, adiposity, and medication use. Further, self-reported outcomes are often assessed using single question items rather than full validated measures. Research on sexual harassment and assault using measured health indices, full multidimensional scales, and comprehensive consideration of confounders is warranted.

Among a well-characterized sample of 304 midlife women, we investigated the relation of a history of sexual harassment and sexual assault to blood pressure (BP), depressed mood, anxiety, and sleep, important health issues impacting midlife women. Elevated BP is a major risk factor for CVD, the leading cause of death in women,11 and important indicator of risk among midlife women who typically develop clinical CVD later in life.12 Depression and anxiety show a doubling in rates in women relative to men,13 and up to half of midlife women report problems with sleep.14,15 We hypothesized that sexual harassment and assault would be associated with higher BP, more depressed mood and anxiety, and poorer sleep after accounting for key confounders.

Methods

304 nonsmoking women aged 40–60 were recruited from the community (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA) via advertisements, mailings, and online message boards. The cohort was originally selected for a study designed to examine the association of menopausal hot flashes and subclinical atherosclerosis as assessed by carotid ultrasound.16 Per original study design, half of the women reported menopausal hot flashes and half reported no hot flashes (see16 for details). Of the 1929 women who underwent telephone screening, 304 were eligible and enrolled. Exclusions, selected based upon their impact on menopausal symptoms and cardiovascular health, included premenopausal status; hysterectomy, oophorectomy; reported history of CVD, arrhythmia, kidney failure, gynecological cancer; current pregnancy; or having used key medications (past 3 months; oral/transdermal estrogen or progesterone, selective estrogen receptor modulators, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), gabapentin, insulin, beta blockers, calcium channel blockers, alpha-2 adrenergic agonists). Procedures were approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board. Participants provided written, informed consent.

Procedures included physical measurements, interviews, and questionnaires. Sexual harassment and assault were assessed from Brief Trauma Questionnaire items developed for the Nurses’ Health Study II17 adapted from the Brief Trauma Interview.18,19 Items assessed workplace sexual harassment: “Have you ever experienced sexual harassment at work that was either physical or verbal?,” and sexual assault: “Have you ever been made or pressured into having some type of unwanted sexual contact? (By sexual contact we mean any contact between someone else and your private parts or between you and someone else’s private parts)”. Response options were yes/no. This measure has high interrater reliability relative to the DSM-IV for presence of Criterion A1 trauma exposure [k=.70].17

Seated BP was measured via a Dinamap device after 10-min rest. Height and weight were measured via a stadiometer and balance beam scale. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated (kg/m2). Depressive symptoms were assessed by the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CESD) scale,20 trait anxiety via the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI),21 and sleep quality via the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)22 considered continuously and via clinical cutpoints (CESD≥16;20 PSQI>5;22 and STAI≥40 as per23 and upper quartile of normative samples21). Demographics and medical history were assessed via structured interview. Women reported current medication use (e.g., for BP: angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, diuretics; sleep: melatonin, GABA alpha agents; anxiety: benzodiazepines; depression: buproprion, tricyclics). Physical activity was assessed via the International Physical Activity Questionnaire24 and snoring with the Berlin Questionnaire.25

Data analyses

PSQI values were natural log transformed for analysis. Differences between participants by harassment or assault history were tested using linear regression, Wilcoxon rank sum, and chi-square tests. Associations between exposures and outcomes were tested in regression models. Covariates were factors associated with the outcome at p<.15, with select variables selected a priori for inclusion (medications and for sleep models snoring and nightshift work). Residual analysis and diagnostic plots were conducted to verify model assumptions. Analyses were performed with SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Models were 2-sided, α=0.05.

Results

Participants were on average 54 years old (Table 1). Nineteen percent of women reported a history of workplace sexual harassment and 22% a history of sexual assault. Ten percent of women reported both sexual harassment and assault. Women with a history of sexual harassment had higher education yet more financial strain. No characteristics varied by sexual assault.

Table 1.

Subject Characteristics (N=304)

| Workplace Sexual Harassment | Sexual Assault | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (N=58, 19%) | No (N=246, 81%) | Yes (N=67, 22%) | No (N=237, 78%) | |

| Age, M (SD) | 53.93 (3.53) | 54.08 (4.09) | 53.73 (4.06) | 54.14 (3.97) |

| Race/ethnicity, N (%) | ||||

| White | 45 (77.59) | 175 (71.14) | 50 (74.63) | 170 (71.73) |

| Non-whitea | 13 (22.41) | 71 (28.86) | 17 (25.37) | 67 (28.27) |

| Education, N (%)b | ||||

| < College | 17 (29.31) | 112 (45.53) | 23 (34.33) | 106 (44.73) |

| ≥ College | 41 (70.69) | 134 (54.47) | 44 (65.67) | 131 (55.27) |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married/Partnered | 28 (48.28) | 142 (57.72) | 32 (47.76) | 138 (58.23) |

| Divorced/Widowed | 14 (24.14) | 64 (26.02) | 17 (25.37) | 61 (25.74) |

| Single | 16 (27.59) | 40 (16.26) | 18 (26.87) | 38 (16.03) |

| Financial strain (yes), N (%)b | 27 (46.55) | 68 (27.98) | 26 (38.81) | 69 (29.49) |

| BMI, M (SD) | 27.85 (6.07) | 29.26 (6.89) | 27.80 (6.20) | 29.32 (6.88) |

| Alcohol use, N (%) | ||||

| < monthly | 21 (36.21) | 109 (44.31) | 29 (43.28) | 101 (42.62) |

| Monthly - < weekly | 20 (34.48) | 77 (31.30) | 23 (34.33) | 74 (31.22) |

| Weekly | 17 (29.31) | 60 (24.39) | 15 (22.39) | 62 (26.16) |

| Leisure physical activity (IPAQ), Median (IQR) | 458 (0,1286) | 396 (0,1298) | 297 (0, 1188) | 438 (0, 1386) |

| Snoring, N (%) | 27 (46.55) | 109 (44.31) | 31 (46.27) | 105 (44.30) |

| Nightshift work, N (%) | 3 (5.17) | 17 (6.91) | 5 (7.46) | 15 (6.33) |

| Medication use | ||||

| BP-lowering | 9 (15.52) | 39 (15.85) | 7 (10.45) | 41 (17.30) |

| Sleep | 2 (3.45) | 12 (4.88) | 1 (1.49) | 13 (5.49) |

| Antidepressants | 1 (1.72) | 5 (2.03) | 1 (1.49) | 5 (2.11) |

| Anxiolytics | 1 (1.72) | 4 (1.63) | 1 (1.49) | 4 (1.69) |

Financial strain: Somewhat hard or very hard paying for basics

Physical activity square root transformed for analysis

Non-white race/ethnicity: African American, Asian, Hispanic, or biracial

varies by harassment p<.05

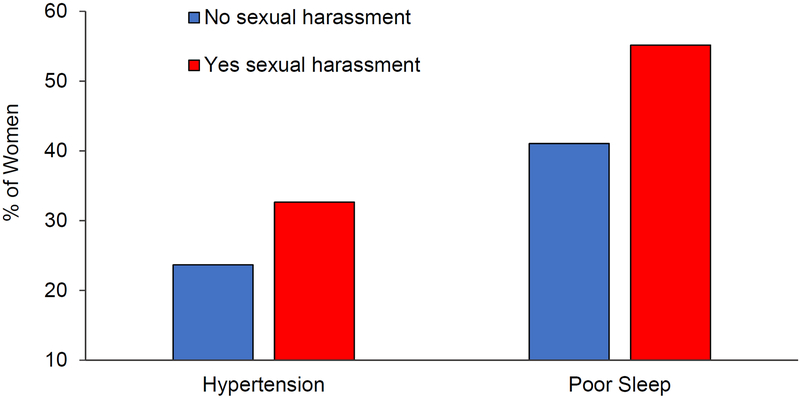

Women with a history of sexual harassment had significantly higher SBP, marginally higher DBP, and significantly poorer sleep quality than women without a history of harassment, adjusting for covariates (Table 2). When considering clinical cutpoints, harassment was associated with significantly higher likelihood of stage 1 or 2 hypertension among women not taking antihypertensive medications [SBP≥130 or DBP≥80 mmHg; OR(95%CI)=2.36 (1.10–5.06), p=.03, multivariable] and of poor sleep consistent with clinical insomnia [OR (95%CI)=1.89 (1.05–3.42), p=.03, multivariable; Figure 1].

Table 2.

Workplace sexual harassment and sexual assault in relation to BP, mental health, and sleep indices

| Sexual Harassment B (SE) |

P Value | Sexual Assault B (SE) |

P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SBP | 3.96 (1.94) | .04 | 1.55 (1.85) | .40 |

| DBP | 2.40 (1.29) | .06 | 1.49 (1.23) | .23 |

| Depressive symptoms | 2.27 (1.21) | .06 | 4.01 (1.13) | .0004 |

| Anxiety | 1.55 (1.43) | .28 | 3.78 (1.34) | .005 |

| Sleep Quality | .15 (.07) | .03 | .24 (.06) | .0002 |

BP, blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure

Note: Sleep quality natural log transformed for analysis

All models adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, education, BMI; Additional covariates in BP models: BP-lowering medication; Depression/anxiety models: antidepressants, anxiolytics; Sleep models: snoring, sleep medication, nightshift work

Figure 1. Relation of sexual harassment to prevalence of hypertension and poor sleep.

Adjusted odds ratios for hypertension: OR (95%CI)=2.36 (1.10–5.06), p=.03; sleep: OR (95% CI)=1.89 (1.05–3.42), p=.03; Hypertension models adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, education, BMI among women not using anti-hypertensive medications; Sleep models adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, education, BMI, snoring, sleep medication, nightshift work

Hypertension: Stage 1 or 2, SBP≥130 or DBP≥80 mmHg

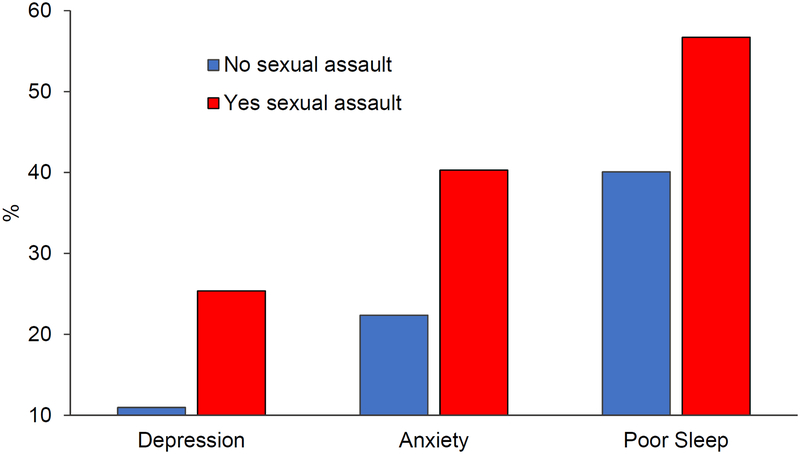

Women with a history of sexual assault had higher depressive symptoms, anxiety, and poorer sleep quality than women without a history of sexual assault (Table 2). Assault was related to significantly higher odds of clinically elevated depressive symptoms [OR(95%CI) =2.86 (1.42–5.77), p=.003, multivariable], anxiety [OR(95%CI=2.26(1.26–4.06), p=.006, multivariable] and poor sleep [OR(95%CI)=2.15 (1.23–3.77), p=.007, multivariable; Figure 2].

Figure 2. Relation of sexual assault to depressed mood, anxiety, and sleep quality.

Adjusted odds ratios for depression: OR (95% CI)=2.86 (1.42–5.77), p=.003; anxiety: OR (95%CI)=2.26 (1.26–4.06), p=.006; sleep: OR (95%CI)= 2.15 (1.23–3.77), p=.007; Depression/anxiety models adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, education, BMI, antidepressants, anxiolytics; sleep models adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, education, BMI, snoring, sleep medication, nightshift work

Discussion

Among these midlife women, 19% of women reported a history of workplace sexual harassment, and 22% of women reported a history of sexual assault. Sexual harassment was related to higher BP and poorer sleep, and sexual assault to depressed mood, anxiety, and poor sleep. Associations persisted adjusting for demographic and biomedical covariates.

Approximately one in five women reported having been sexual harassed or sexually assaulted. Although high, these rates are lower than those of national samples,1,2 Variations in estimates can arise from sample characteristics, assessment methods, and willingness of participants to report these sensitive experiences. Our sample was somewhat lower risk on sociodemographic and physical characteristics than the average population, as we excluded women who were smokers, had undergone hysterectomy, or were using common antidepressants and certain cardiovascular medications. Few characteristics distinguished women who had been sexually harassed or assaulted, with the exception that women who were sexually harassed were more highly educated yet more financially strained. Notably, women who are younger or are in more precarious employment situations are more likely to be harassed, and financially stressed women can lack the financial security to leave abusive work situations.3 Why more highly educated women here were more likely to be harassed is unclear; these women may more often be employed in male-dominated settings, be more knowledgeable about what constitutes sexual harassment, or be perceived as threatening, as sexual harassment is an assertion of hierarchical power relations.3,26

This study examines sexual harassment and assault in relation to measured BP, an advance over previous work relying largely upon self-report. An exception is work by Krieger and colleagues who examined workplace hazards in relation to BP among low-income participants, finding that only sexual harassment was associated with SBP among women.27 Notably, the magnitude of increase in SBP observed here with a history of harassment (approximately 4 mmHg in SBP) is clinically significant (e.g., a 20% increased risk for CVD).28 Importantly, harassed women not taking anti-hypertensives had an over two-fold odds of BP consistent with hypertension.

Sexual assault was related to poorer mental health. Assaulted women had almost three-fold odds of symptoms consistent with major depressive disorder and over two-fold odds of elevated anxiety. Conversely, sexual assault appeared less related to BP; a relation that may depend on the severity or chronicity of the victimization history.29 Sexual assault and harassment were each associated with a two-fold odds of poor sleep consistent with clinical insomnia. Notably, poor sleep,30,31 depressed mood,32 and anxiety33 are themselves linked adverse physical health outcomes.

This work has limitations. Study exposures were assessed via two questions. Future work should employ a full multidimensional scale that measures the severity and chronicity of exposures. Women recalled harassment and assault and reported exclusionary medical conditions that may incorporate reporting biases. The sample had somewhat limited representation of racial/ethnic minority groups and reflected several exclusions; thus, findings may not be generalizable to all women. Future work should include more diverse samples. This work incorporates multiple comparisons. Finally, this study cannot establish the causality or temporality of exposures in relation to outcomes.

This study has several strengths. We considered sexual harassment and assault, prevalent yet understudied exposures in women. We considered measured BP and a range of mental health indices assessed with full, validated scales. We adjusted for a range of key covariates. We studied these associations in a well-characterized sample of women.

Among midlife women, workplace sexual harassment was associated with higher BP and poorer sleep, and sexual assault with depressed mood, anxiety, and poorer sleep. Future work should consider whether preventing or mitigating sexual harassment and sexual assault can improve women’s mental and cardiovascular health. Given the high prevalence of sexual harassment and assault, addressing these prevalent and potent social exposures may be critical to promoting health and preventing disease in women.

Key Points

Question:

Do women with a history of sexual harassment or sexual assault have higher blood pressure, greater depression and anxiety, and poorer sleep than women without this history?

Findings:

Among 304 nonsmoking midlife women, women with a history of workplace sexual harassment had significantly higher odds of hypertension and clinically poor sleep than women without this history, adjusting for covariates. Women with a history of sexual assault had significantly higher odds of clinically significant depressive symptoms, anxiety, and poor sleep than women without this history, adjusting for covariates.

Meaning:

Sexual harassment and sexual assault have implications for women’s health.

Acknowledgements

Drs. Thurston, von Känel, Koenen, and Matthews were responsible for the overall design of the study. Dr. Thurston oversaw the overall conduct of the study. Drs. Thurston and Chang were responsible for the statistical analysis. All authors made substantial contributions to the interpretation of the data, drafting, and revision of the article. All authors provided final approval of the article and are accountable for all aspects of the work. Dr. Thurston had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Disclosures: Thurston: MAS Innovations, Procter & Gamble, Pfizer (consulting); no other authors have disclosures to declare.

Funding: This work was supported by the supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (R01HL105647, K24123565 to Thurston) and the University of Pittsburgh Clinical and Translational Science Institute (NIH Grant UL1TR000005). The National Institutes of Health funded this work and approved the initial study design, but was not involved in the conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; nor the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Willness CR, Steel P, Lee K. A meta-analysis of the antecedents and consequences of workplace sexual harassment. Pers. Psychol 2007;60:127–162. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Breiding M, Smith S, Basile K, Walters M, Chen J, Merrick M. Prevalence and Characteristics of Sexual Violence, Stalking, and Intimate Partner Violence Victimization — National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey, United States, 2011. MMWR. 2014;63(SS08):1–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McDonald P Workplace sexual harassment 30 years on: A review of the literature. International Journal of Management Reviews. 2012;14:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adverse health conditions and health risk behaviors associated with intimate partner violenced, United States, 2005. In: (CDC) CfDCaP, ed. Vol 572008:113–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campbell J, Jones AS, Dienemann J, et al. Intimate partner violence and physical health consequences. Arch. Intern. Med May 27 2002;162(10):1157–1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vives-Cases C, Ruiz-Cantero MT, Escriba-Aguir V, Miralles JJ. The effect of intimate partner violence and other forms of violence against women on health. J Public Health (Oxf). March 2011;33(1):15–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mason SM, Wright RJ, Hibert EN, et al. Intimate partner violence and incidence of type 2 diabetes in women. Diabetes Care. May 2013;36(5):1159–1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mason SM, Wright RJ, Hibert EN, Spiegelman D, Forman JP, Rich-Edwards JW. Intimate partner violence and incidence of hypertension in women. Ann. Epidemiol August 2012;22(8):562–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bower GH. Mood and memory. Am. Psychol 1981;36(2):129–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lillie-Blanton M, Rushing O, Ruiz S, Mayberry R, Boone L. Racial/Ethnic Differences in Cardiac Care: The Weight of the Evidence. Menlo Park, California: The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation and American College of Cardiology; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benjamin EJ, Virani SS, Callaway CW, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2018 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. March 20 2018;137(12):e67–e492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mosca L, Benjamin EJ, Berra K, et al. Effectiveness-based guidelines for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in women−−2011 update: a guideline from the american heart association. Circulation. March 22 2011;123(11):1243–1262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hankin BL, Young JF, Abela JR, et al. Depression from childhood into late adolescence: Influence of gender, development, genetic susceptibility, and peer stress. J. Abnorm. Psychol November 2015;124(4):803–816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kravitz HM, Ganz PA, Bromberger J, Powell LH, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Meyer PM. Sleep difficulty in women at midlife: a community survey of sleep and the menopausal transition. Menopause. Jan-Feb 2003;10(1):19–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shaver JL, Woods NF. Sleep and menopause: a narrative review. Menopause. August 2015;22(8):899–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thurston RC, Chang Y, Barinas-Mitchell E, et al. Menopausal hot flashes and carotid intima media thickness among midlife women. Stroke. December 2016;47(12):2910–2915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koenen KC, De Vivo I, Rich-Edwards J, Smoller JW, Wright RJ, Purcell SM. Protocol for investigating genetic determinants of posttraumatic stress disorder in women from the Nurses’ Health Study II. BMC Psychiatry. May 29 2009;9:29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schnurr P, Spiro A, Vielhauer M, Findler M, Hamblen J. Trauma in the lives of older men: findings from the Normative Aging Study. J. Clin. Geropsychol 2002;8:175–187. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schnurr P, Lunney C, Sengupta A, Spiro A III. A longitudinal study of retirement in older male veterans. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol 2005;73(3):561–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl. Psychol. Meas 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spielberger CD. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res May 1989;28(2):193–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Julian LJ. Measures of Anxiety. Arthritis Care Res. (Hoboken). 2011;63(011): 10.1002/acr.20561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Craig CL, Marshall A, Sjostrom M, et al. International Physical Activity Questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc 2003;35(8):1381–1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Netzer NC, Stoohs RA, Netzer CM, Clark K, Strohl KP. Using the Berlin Questionnaire to identify patients at risk for the sleep apnea syndrome. Ann. Intern. Med October 5 1999;131(7):485–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schweinle W, Cofer C, Schatz S. Men’s empathic bias, empathic inaccuracy, and sexual harassment. Sex Roles. 2008;60(1):142–150. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krieger N, Chen JT, Waterman PD, et al. The inverse hazard law: blood pressure, sexual harassment, racial discrimination, workplace abuse and occupational exposures in US low-income black, white and Latino workers. Soc. Sci. Med December 2008;67(12):1970–1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jones DW, Hall JE. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure and evidence from new hypertension trials. Hypertension. January 2004;43(1):1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Renner LM, Spencer RA, Morrissette J, et al. Implications of Severe Polyvictimization for Cardiovascular Disease Risk Among Female Survivors of Violence. J. Interpers. Violence August 1 2017:886260517728688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cappuccio FP, Cooper D, D’Elia L, Strazzullo P, Miller MA. Sleep duration predicts cardiovascular outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur. Heart J June 2011;32(12):1484–1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buysse DJ. Insomnia. JAMA. February 20 2013;309(7):706–716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lett HS, Blumenthal JA, Babyak MA, et al. Depression as a risk factor for coronary artery disease: evidence, mechanisms, and treatment. Psychosom. Med May-Jun 2004;66(3):305–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thurston RC, Rewak M, Kubzansky LD. An anxious heart: anxiety and the onset of cardiovascular diseases. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis May-Jun 2013;55(6):524–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]