Abstract

Objectives

To determine whether or not the presence of pleural and/or pericardial effusion can be used prenatally as an ultrasonographic marker for the differential diagnosis between diaphragmatic eventration and diaphragmatic hernia.

Methods

We present two case reports of non-isolated diaphragmatic eventration associated with pleural and/or pericardial effusion. Additionally, we reviewed the literature for all cases of congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) and diaphragmatic eventration that met the following criteria: (1) prenatal diagnosis of a diaphragmatic defect and (2) definitive diagnosis by autopsy or surgery. The frequencies of pleural effusion, pericardial effusion, and hydrops were compared between the two conditions using the Fisher’s exact test. A subanalysis was conducted of cases with isolated diaphragmatic defects (i.e. diaphragmatic defects not associated with hydrops and other major structural or chromosomal anomalies).

Results

A higher proportion of fetuses with diaphragmatic eventration had associated pleural and pericardial effusions compared with fetuses with diaphragmatic hernia (58% (7/12) vs. 3.7% (14/382), respectively, P < 0.001). This observation remained true when only cases of diaphragmatic defects not associated with hydrops and other major structural or chromosomal anomalies were compared (29% (2/7) with eventration vs. 2.2% (4/178) with CDH, P < 0.02).

Conclusions

The presence of pleural and/or pericardial effusion in patients with diaphragmatic defects should raise the possibility of a congenital diaphragmatic eventration. This information is clinically important for management and counseling because the prognosis and treatment for CDH and congenital diaphragmatic eventration are different.

Keywords: congenital diaphragmatic hernia, diaphragmatic eventration, pericardial effusion, pleural effusion

INTRODUCTION

Congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) is a defect in the diaphragm that allows the displacement of abdominal viscera into the thoracic cavity. It is associated with a high perinatal mortality rate due to lung hypoplasia and associated chromosomal or syndromic anomalies1–12 It has been proposed that this defect, which occurs in approximately one in 2000–2700 live births4,10,11,13, is due to a delayed closure of the communication between the thorax and the abdomen, which normally takes place during the 6th week of development14,15

Diaphragmatic eventration is characterized by the cephalic displacement of all or a portion of an intact diaphragm owing to a weakness believed to be secondary to defective diaphragmatic muscularization. In contrast to CDH, there is no communication between the abdominal and thoracic cavities in cases of eventration. Jean Louis Petit first recognized this disorder in 1774, and the term ‘eventration’, meaning ‘out of the venter (belly)’, was coined by Beclard in 191616–19 Using data from the Northern Region Congenital Abnormality Survey between 1985 and 1997, Dillon et al found that 7% (14/201) of diaphragmatic defects are eventrations20.

CDH is associated with high perinatal and neonatal mortality rates, and surgical repair is often complicated by postoperative bleeding, high intraabdominal pressures, and detachment of the patch leading to reherniation21–25. In contrast, diaphragmatic eventration is associated with a lower neonatal mortality rate26–28 and does not always require surgical repair29. Therefore, accurate prenatal diagnosis is important for parental counseling and postnatal management.

The objectives of this study were to: (1) report two cases of diaphragmatic eventration associated with pleural and/or pericardial effusions, and (2) determine whether the presence of pleural and/or pericardial effusions may be used as a marker for the differential diagnosis between CDH and diaphragmatic eventration.

METHODS

Two cases of diaphragmatic eventration associated with other structural anomalies are described. Both patients gave written informed consent prior to participation in the study, which was conducted under protocols approved by the Institutional Review Board of both Wayne State University and the National Institutes of Child Health and Human Development.

A systematic review of the literature was performed for all cases of diaphragmatic hernia and eventration that met the following criteria: (1) prenatal diagnosis of a diaphragmatic defect and (2) definitive diagnosis by autopsy or surgery. The following keywords were used: (i) prenatal diaphragmatic eventration (17 articles); (ii) congenital diaphragmatic hernia and prenatal diagnosis (414 articles), and pleural effusion (36 articles), and hydrops (37 articles), and pericardial effusion (12 articles); (iii) congenital diaphragmatic eventration and prenatal diagnosis (12 articles), and pleural effusion (three articles), and hydrops (two articles), and pericardial effusion (one article); (iv) diaphragmatic eventration and pleural effusion (19 articles), and hydrops (two articles), and pericardial effusion (three articles). We evaluated the associated anomalies and outcomes of the two conditions. The frequencies of associated abnormalities (e.g. pleural effusion, pericardial effusion and hydrops) were compared between the two conditions using the Fisher’s exact test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. We performed a subanalysis limited to cases with only diaphragmatic defects without hydrops, or major structural or chromosomal anomalies, and which met the aforementioned criteria.

RESULTS

Case 1

A 20-year-old Caucasian woman, G2P0010, was referred to our unit at 21 weeks with the following ultrasound findings: deviation of the cardiac axis to the left, single umbilical artery and severe right pleural effusion. A subsequent ultrasound scan at 22 weeks’ gestation demonstrated fetal hydrops with ascites, bilateral pleural effusion and skin edema. Examination of the chest at the level of the four-chamber view of the heart revealed a mediastinal shift to the left, and a mass occupying the right thoracic cavity whose vascular supply that appeared to come from the liver (Figure 1 and Figure 2). Based on these findings, CDH was considered the most likely diagnosis. An amniocentesis was performed and revealed a normal female karyotype (46, XX).

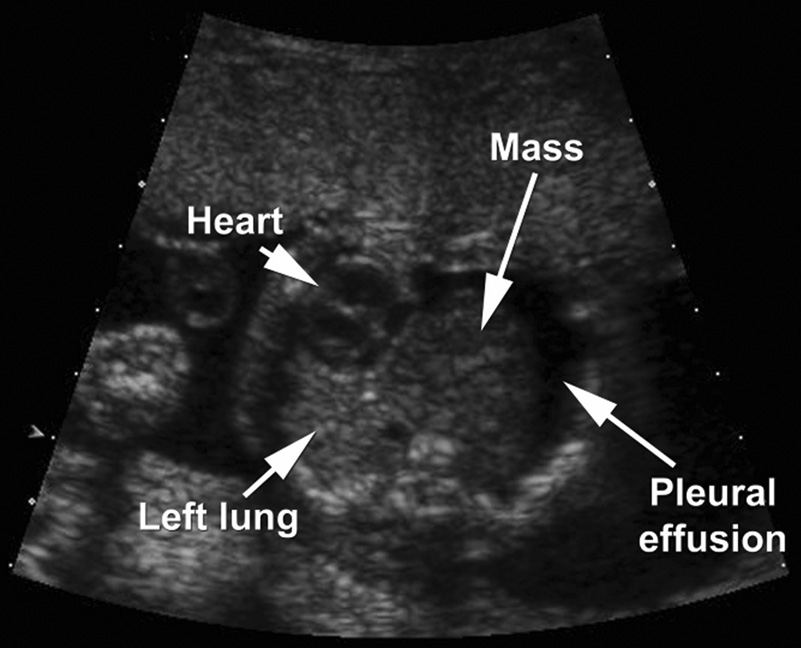

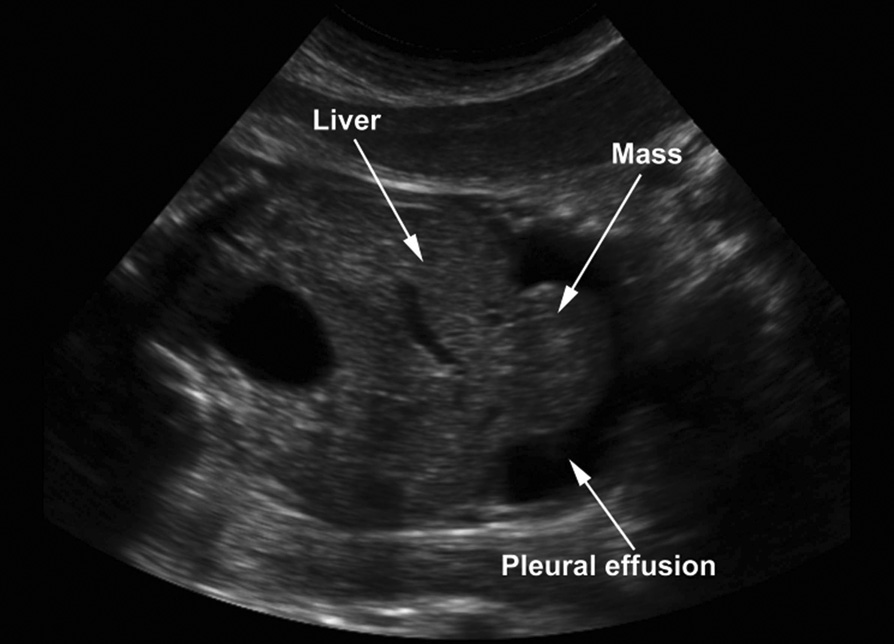

Figure 1.

Ultrasound image showing a transverse section through the fetal chest at 22 weeks’ gestation. A mass is visualized on the right side of the thorax, displacing the heart to the left side. Bilateral pleural effusion is observed.

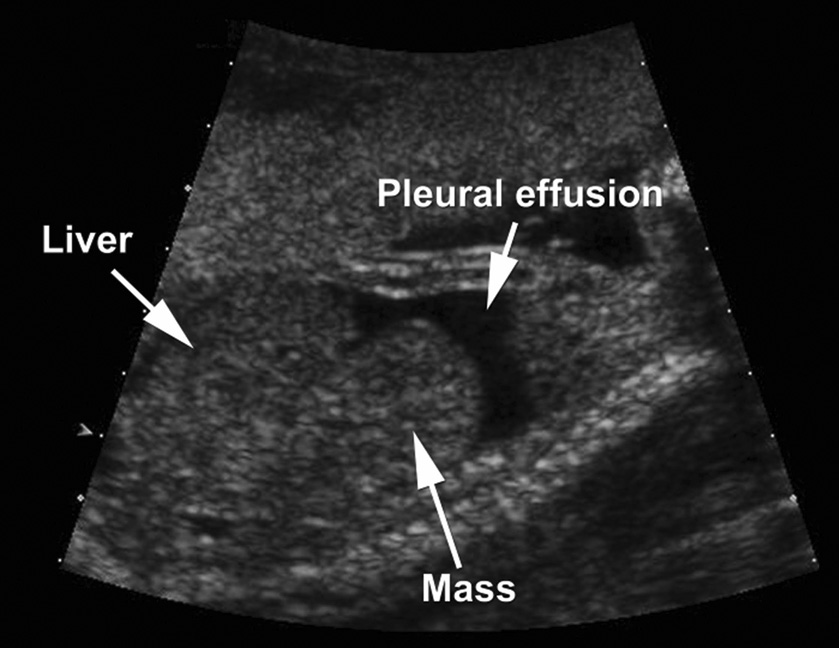

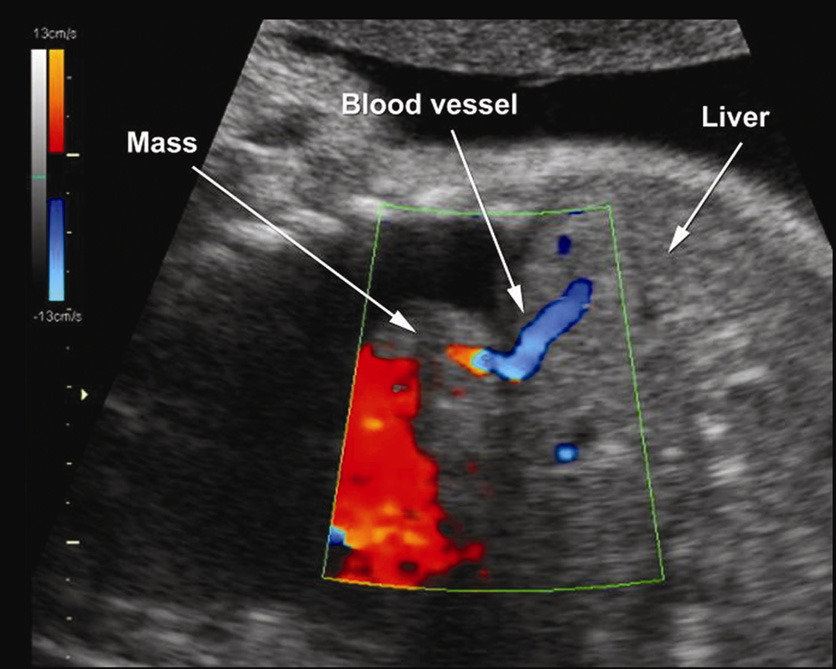

Figure 2.

(a) Ultrasound image showing a right parasaggital section through the fetal thorax and abdomen. A mass with echotexture similar to that of the fetal liver is visualized protruding from the fetal abdomen into the thorax. (b) Power Doppler demonstrates vessels within the mass that connect to hepatic vessels, suggesting that the mass is indeed composed of liver tissue.

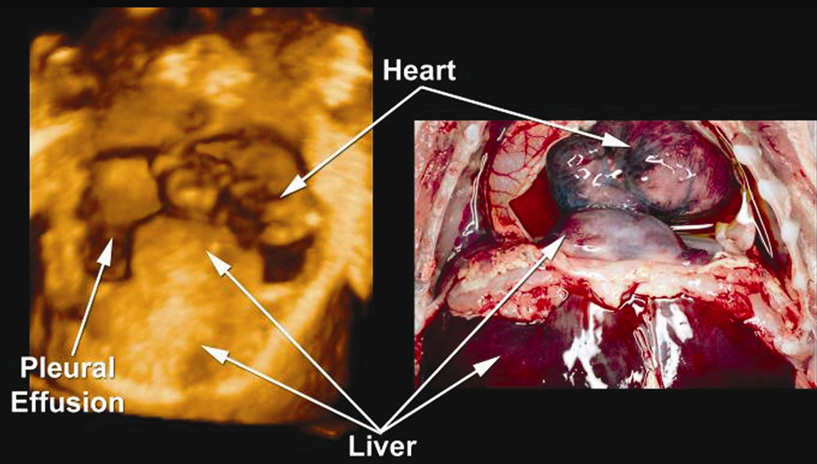

After counseling, the patient decided to terminate the pregnancy. A female fetus weighing 540 g was delivered vaginally at 23 weeks’ gestation after induction of labor. Autopsy revealed a right diaphragmatic eventration containing herniated liver (Figure 3). Bilateral pleural effusions, pulmonary hypoplasia and hypertelorism were also noted. All other ultrasound findings were confirmed.

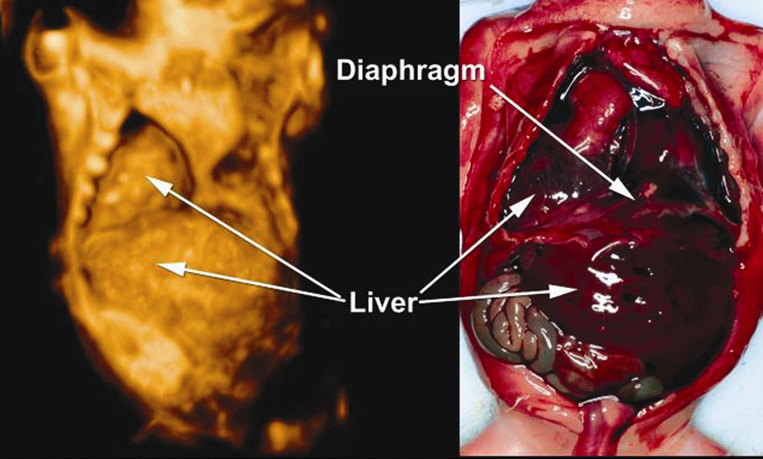

Figure 3.

Anteroposterior view of a three-dimensional ultrasound rendered image of the fetal thorax and abdomen, demonstrating diaphragmatic Eventration (left) and correlation with autopsy findings (right).

Case 2

A 28-year-old Caucasian woman, GP5005, with little prenatal care had an ultrasound examination in our unit at 30 weeks’ gestation. A detailed scan demonstrated polyhydramnios, a large pericardial effusion and a possible central diaphragmatic hernia (Figure 4). Additionally, multiple cardiac anomalies were visualized, including double-outlet right ventricle, transposition of great arteries, as well as ventricular and atrial septal defect. A genetic amniocentesis was performed demonstrating a normal female karyotype (46, XX). At 32 weeks’ gestation, the patient was readmitted to the hospital because of preterm premature rupture of membranes. At that time, erythrocymin and clindamycin were administrated. The patient showed no signs or symptoms of clinical chorioamniontis. She remained in the hospital until 34 weeks’ gestation, when no fetal heart rate was detected. The patient was induced, and delivered a 1780-g stillborn fetus vaginally.

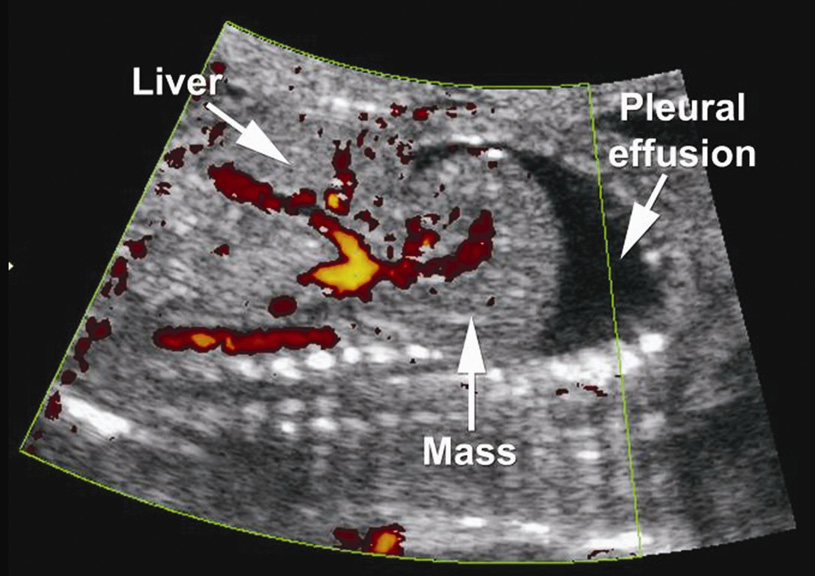

Figure 4.

(a) Coronal ultrasound image through the fetal thorax and abdomen. A mass is visualized protruding into the fetal chest from the fetal abdomen. The echotexture is similar to that of the liver. (b) Hepatic blood vessel extending from the abdomen to the thorax, confirming that the liver has herniated through the defect.

An autopsy was performed and revealed diaphragmatic eventration involving the anterior midline diaphragm and containing liver (Figure 5). Pericardial effusion was noted. In addition, a triphalangeal left thumb and bifid right thumb were observed. All other anomalies seen by ultrasound were confirmed. Histological examination of the placenta revealed acute chorioamnionitis, funisitis and chorionic vasculitis.

Figure 5.

Anteroposterior view of a three-dimensional ultrasound rendered image of the fetal thorax and abdomen, demonstrating diaphragmatic eventration (left) and correlation with autopsy (right).

Literature review

A total of 127 articles were reviewed, 61 of which contained cases that met our inclusion criteria1,13,30–88 These articles reported on 4208 cases of diaphragmatic hernia diagnosed prenatally, 382 of which were explicitly confirmed by surgery or autopsy. Of these cases, 3.7% (14/382) had hydrops, pericardial effusion or pleural effusion (Table I)31,32,36,41,48,52,73–75,79,81. Twelve cases of diaphragmatic eventration, including ours, are presented in Table 230,31,35,37,39,40,45,71,80,88. Eight of these cases were diagnosed prenatally as diaphragmatic defects, whereas four were diagnosed in the neonatal period. Three cases of eventration were not verified by surgery or autopsy; however, ultrasound examination, X-ray or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) clearly demonstrated the diaphragm over the thoracic mass. Of the cases of eventration, 58% (7/12) had hydrops, pericardial effusion or pleural effusion. Following our criteria strictly, 60% (3/5) of diaphragmatic defects detected prenatally and subsequently confirmed to be diaphragmatic eventration by surgery or autopsy had hydrops, pericardial effusion or pleural effusion.

Table I.

Cases of diaphragmatic hernia with hydrops, pericardial effusion or pleural effusion

| Study | Diaphragmatic hernia | Confirmation of diagnosis | Presence of pleural / pericardial effusion | Associated anomalies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ake et al (1991) | 1 right CDH (Morgagni) | Surgery | Pericardial effusion | None |

| Benacerraf et al (1986) | 1 right CDH | Surgery | Hydrothorax, fetal hydrops | Fetal ascites, polyhydramnios |

| Blott et al (1988) | 2 CDH (1 Left / 1 Bilateral) | Surgery and autopsy | Pleural effusion (2), hydrops (1) | None |

| Bollman et al (1995) | 2 CDH | Autopsy | Hydrops (2) | Monosomy X0, cleft palate, clitoris hypertrophy |

| Hyodo et al (2002) | 1 left CDH (Bochdalek) | Surgery | Pleural effusion (due to antenatal gastrointestinal perforation) | Ascites (due to antenatal gastrointestinal perforation) |

| Ikeda et al (2002) | 1 CDH (Morgagni) | Surgery | Pericardial effusion | Intrapericardial mass |

| Lau et al (1997) | 1 left CDH | Surgery | Pleural effusion | Ascites |

| Nakayama et al (1985) | 1 right CDH | Autopsy | Small pleural effusion | Ascites, atrial septal defect, ventricular septal defect, double outlet right ventricle, bilateral hydronephrosis, hydroureter cleft palate, 2-vessel cord |

| Robnett-Filly et al (2003) | 1 central hernia | Surgery | Bilateral pleural effusion, pericardial effusion | Ventricular septal defect |

| Sydorak et al (2002) | 2 left CDH | Autopsy in both cases | Hydrops (2) | None |

| Varlet et al (2003) | 1 left diaphragmatic aplasia | Autopsy | Hydrops | Cystic hygroma, asplenia, duodenal atresia, camptodactyly of the second and third right fingers without distal digital hypoplasia |

Table II.

Cases of diaphragmatic eventration included in the study.

| Study | Diaphragmat ic eventration | Diagnosis | Confirmation of diagnosis | Presence of pleural / pericardial effusion | Associated anomalies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iliff et al (1983) | 1 central | Neonatal diagnosis | Surgery | Pleural effusion | Polyhydramnios |

| Vijayaraghava n (1988) | 1 central | Neonatal diagnosis | Surgery | Pericardial effusion | None |

| Nakayama et al (1985) | 1 right-sided | Neonatal diagnosis | Autopsy (died) | Pleural effusion, hydrops, and ascites | Polyhydramnios |

| de Fonseca et al (1987) | 1 left-sided | Neonatal diagnosis | Autopsy (died) | Pleural and pericardial effusion | None |

| Jurcak-Zaleski et al (1990) | 1 right-sided | Correct prenatal diagnosis | Diaphragm visible in ultrasound | None | None |

| Tsukahara et al (2001) | 1 left-sided | Correct prenatal diagnosis | Diaphragm visible in X-ray and MRI | None | None |

| Thiagarajah et al (1990) | 1 left-sided | Correct prenatal diagnosis | X-ray and ultrasound | None | None |

| Yang (2003) | 1 left-sided | Incorrect prenatal diagnosis (CDH) | Surgery | None | None |

| Yang et al (2005) | 1 right-sided Prenatal | Incorrect prenatal diagnosis (partial anomalous pulmonary venous connection with right atrial enlargement) | Surgery | None | Polyhydramnios, right atrial enlargement (found to be an artifact due to external compression) |

| Narayan et al (1993) | 1 left-sided | Incorrect prenatal diagnosis (hernia) | Autopsy (died) | Pleural effusion, fetal ascites | None |

| Our case | 1 right-sided | Incorrect prenatal diagnosis (CDH) | Autopsy (termination of pregnancy) | Fetal hydrops, ascites, bilateral pleural effusion | two-vessel cord |

| Our case | 1 central | Incorrect prenatal diagnosis (CDH) | Autopsy (died) | Pericardial effusion | Polyhydramnios, double outlet right ventricle, transposition of great arteries, ventricular septal defect, atrial septal defect, triphalangeal left thumb and bifid right thumb |

Using Fisher’s exact test, we found that pleural effusion, pericardial effusion and hydrops were significantly more likely to be found in cases of diaphragmatic eventration than in cases of CDH (58% (7/12) vs. 3.7% (14/382), respectively, P <0.001).

Subanalysis excluding cases of diaphragmatic defects with hydrops and major structural or chromosomal anomalies

Because the association of CDH with hydrops has been linked to a high mortality rate, these cases were excluded from this subanalysis. By limiting our cases to CDH without hydrops and without major structural or chromosomal anomalies, 38 articles31–34,36,38,41,42,45,48,49,51–57,59–61,63–70,72,74,76–78,84–87 reported on 178 cases of CDH and seven articles reported on seven cases of diaphragmatic eventration30,37,39,40,71,80,88. Fetuses with diaphragmatic eventration had a consistently higher rate of associated pleural or peridcardial effusion than those with CDH (29% (2/7) vs. 2.2% (4/178), respectively, P < 0.02).

DISCUSSION

We present two cases of non-isolated diaphragmatic eventration associated with pleural and/or pericardial effusions. One of our patients represents a rare case of a central diaphragmatic eventration. Less than 1% of diaphragmatic defects involve the septum transversum89. The most common defect of the septum transversum occurs as a pentad of associated anomalies known as Pentalogy of Cantrell, which includes a midline supraumbilical anterior abdominal wall defect, a defect in the lower sternum, absence of the anterior central diaphragm, absence of the diaphragmatic pericardium, and congenital heart defects90. Yuan et al. examined the possible etiology of a central diaphragmatic hernia91. Using a murine model lacking the Slit3 protein, the authors found that the mice develop a central diaphragmatic eventration. In Slit3 null mice, the central tendon region of the diaphragm fails to separate from liver tissue due to abnormalities in morphogenesis. The authors proposed that Slit3 may play a role in regulating cell proliferation, synthesis of extracellular matrix molecules, and migration of mesothelial cells to the diaphragm.

In this study, we found that pleural and pericardial effusions are significantly more likely to be found in cases of diaphragmatic eventration than in cases of CDH, regardless of whether or not the diaphragmatic defects were associated with hydrops, or major chromosomal or structural anomalies. This is important because the outcome and management of these conditions is different. Therefore, an accurate diagnosis has implications for prenatal counseling.

The overall mortality rate (perinatal and neonatal) in cases of CDH without major structural or chromosomal anomalies ranges from 22 to 70%13,49,50,53,55,59,67,72,77,85. According to the CDH Study Group the mortality rate for infants with CDH is 37%92. On the other hand, mortality in cases of diaphragmatic eventration is considerably lower. In 100 cases of eventration reported by Beck and Motsay among 2500 chest X-rays of neonates, three patients had severe symptoms and only one died, from respiratory insufficiency26. Wayne et al. documented the outcomes of 48 patients with congenital diaphragmatic eventration, associated with 10 cases of hypoplastic ribs, coarctation of the aorta, cleft palate, hemivertebrae and heart disease. Three of the infants died, one from massive pneumonia associated with bilateral total eventrations, and the other two from severe pulmonary hypoplasia associated with total right-sided eventration29. Yazici et al. presented 33 patients with diaphragmatic eventration between the ages of 3 days to 12 years who underwent surgical plication for symptoms including respiratory distress, fever, cough, recurrent pneumonia, bronchitis, decreased breathing sound and cyanosis. One patient also had tetralogy of Fallot. Two of the 33 patients died after operation because of cardiorespiratory complications28. Tsugawa et al. reported on 50 patients ranging in age from age 4 days to 7 years with diaphragmatic eventrations. Twenty-five of these patients had congenital muscular deficiency of the diaphragm (as opposed to phrenic nerve injury), and two patients died after surgery from cardiac disease27. The mortality rate in cases of diaphragmatic eventration according to these four studies is therefore between 1% and 8% (1/100, 3/48, 2/33 and 2/25). The mortality rate associated with cases of diaphragmatic eventration included in our analysis was considerably higher (42%, 5/12). This may be due to the fact that our initial criteria were to include only cases of eventration verified by surgery or autopsy, with exclusion of the asymptomatic, milder cases.

The management of diaphragmatic eventration and CDH also differs. Diaphragmatic eventrations are repaired through surgical plication of the membranes in an accordion-like fashion93. The procedure is considered easy to perform, either through the abdomen or the chest, and has a low complication rate27,28,94,95. De Vries et al. reported no postoperative complications in 13 patients under 1 year of age with eventration due to phrenic nerve injury94. In a study by Schwartz and Filler, pneumothorax was reported in one of the six cases of diaphragmatic placation performed to repair eventration caused by phrenic nerve paralysis95. However, in the study by Wayne et al., 36% (5/14) of children who underwent diaphragmatic plication had complications from the surgery involving phrenic nerve palsy, and breakdown of the suture line resulting in reherniation29. Diaphragmatic eventrations also differ from CDH in that eventrations do not always require surgery. In the study by Wayne et al., only 23% (11/48) of patients with congenital diaphragmatic eventration were symptomatic and required surgical repair. Of note, eight had total eventration, the more severe form of the defect29. In contrast, the management of diaphragmatic hernia involves inserting a patch over the defect or reconstructing the diaphragm from surrounding muscle. Complications such as postoperative bleeding, high intra-abdominal pressures, and detachment of the patch with subsequent reherniation can arise depending on the type of repair (patch or primary) and the seize of the hernia21,24,25,96. Skari et al. reported a complication rate of 39% in 129 cases of CDH with symptoms appearing before 24 h of postnatal life. Among these neonates, reoperation was performed in 16% of cases. In neonates presenting with symptoms after 24 h of postnatal life, only 7% had postoperative complications and 4% were reoperated97. In a study by Jaillard et al., which excludes cases with associated lethal congenital anomalies, surgical repair was performed in 59 infants. Of these cases, 37% were repaired with a prosthetic patch and complications occurred in 22%; reoperation was performed in four infants owing to bowel obstruction, three infants developed chylothorax, CDH recurred in five infants, and one infant developed a superficial wound infection23. Moss et al. reported on 45 children in whom a prosthetic patch was used to repair the CDH and 41% required reoperation because of reherniation22. Grethel et al. described 72 newborns who underwent patch repair for CDH, of whom 40% had recurrence of the hernia and 6% developed small bowel obstruction25.

The mechanism for accumulation of fluid in the pericardial or pleural sac is unknown. In cases of diaphragmatic eventration, it may be due to mechanical irritation of the membranes or fluid crossing the thin membrane of the diaphragm as a result of the negative pressure within the thoracic cavity30,98. It has been proposed that pleural effusion in the case of a right-sided diaphragmatic hernia with protruding liver may be a result of obstruction to hepatic venous outflow causing vascular congestion and subsequent transudative weeping of the hepatic surface35,99–101.

MRI has been used to aid prenatal diagnosis. No study has compared ultrasound examination and MRI for the diagnosis of congenital diaphragmatic eventration. A few case reports, however, are available71,102,103. Louie et al. presented a 29-day-old female neonate who presented with respiratory distress102. Diaphragmatic eventration was diagnosed with both ultrasonography and MRI102. In a case series by Levine et al., an ultrasound examination on a 23-week-old fetus revealed eventration of the diaphragm and probable sequestration. Postnatal MRI confirmed the presence of an intact diaphragm103. Tsukahara et al. presented a 35-week fetus with eventration discovered by ultrasound scan and confirmed by MRI71. In these three cases, MRI served to confirm the ultrasound diagnosis. The two imaging techniques have been evaluated more extensively in cases of CDH. Matsuoka et al. compared ultrasound examination and MRI in diagnosing congenital thoracic abnormalities. In the three cases of CDH examined, both ultrasound scan and MRI provided an accurate diagnosis of the defect. In the study by Levine et al., 21 fetuses with suspected CDH after ultrasonography were examined, and 18 final diagnoses of CDH were made after MRI103. Hubbard et al. examined 38 fetuses with a confirmed diagnosis of CDH. Thirty-five of these cases (89%) were detected by ultrasound examination, whereas all 38 were detected by MRI.

In summary, we describe two cases of non-isolated diaphragmatic eventration associated with pleural effusion, pericardial effusion or hydrops. We also reviewed the literature on CDH and eventration, and found that these findings are more often associated with eventration than with CDH. The presence of pleural or pericardial effusion in patients with suspected CDH should raise the possibility of a congenital diaphragmatic eventration. This information is clinically important for management and counseling because the prognosis and treatment of the two conditions are different.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, NIH, DHHS.

Reference List

- 1.Adzick NS, Vacanti JP, Lillehei CW, O'Rourke PP, Crone RK, Wilson JM. Fetal diaphragmatic hernia: ultrasound diagnosis and clinical outcome in 38 cases. J Pediatr Surg. 1989;24:654–657. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(89)80713-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bagolan P, Casaccia G, Crescenzi F, Nahom A, Trucchi A, Giorlandino C. Impact of a current treatment protocol on outcome of high-risk congenital diaphragmatic hernia. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39:313–318. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2003.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bedoyan JK, Blackwell SC, Treadwell MC, Johnson A, Klein MD. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia: associated anomalies and antenatal diagnosis. Outcome-related variables at two Detroit hospitals. Pediatr Surg Int. 2004;20:170–176. doi: 10.1007/s00383-004-1138-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colvin J, Bower C, Dickinson JE, Sokol J. Outcomes of congenital diaphragmatic hernia: a population-based study in Western Australia. Pediatrics. 2005;116:e356–e363. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Graham G, Devine PC. Antenatal diagnosis of congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Semin Perinatol. 2005;29:69–76. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guibaud L, Filiatrault D, Garel L, Grignon A, Dubois J, Miron MC, Dallaire L. Fetal congenital diaphragmatic hernia: accuracy of sonography in the diagnosis and prediction of the outcome after birth. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996;166:1195–1202. doi: 10.2214/ajr.166.5.8615269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hubbard AM, Crombleholme TM, Adzick NS, Coleman BG, Howell LJ, Meyer JS, Flake AW. Prenatal MRI evaluation of congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Am J Perinatol. 1999;16:407–413. doi: 10.1055/s-1999-6821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lago P, Meneghini L, Chiandetti L, Tormena F, Metrangolo S, Gamba P. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia: intensive care unit or operating room? Am J Perinatol. 2005;22:189–197. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-866602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shaw KS, Filiatrault D, Yazbeck S, St Vil D. Improved survival for congenital diaphragmatic hernia, based on prenatal ultrasound diagnosis and referral to a combined obstetric-pediatric surgical center. J Pediatr Surg. 1994;29:1268–1269. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(94)90821-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stege G, Fenton A, Jaffray B. Nihilism in the 1990s: the true mortality of congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Pediatrics. 2003;112:532–535. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.3.532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tonks A, Wyldes M, Somerset DA, Dent K, Abhyankar A, Bagchi I, Lander A, Roberts E, Kilby MD. Congenital malformations of the diaphragm: findings of the West Midlands Congenital Anomaly Register 1995 to 2000. Prenat Diagn. 2004;24:596–604. doi: 10.1002/pd.908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Witters I, Legius E, Moerman P, Deprest J, Van Schoubroeck D, Timmerman D, Van Assche FA, Fryns JP. Associated malformations and chromosomal anomalies in 42 cases of prenatally diagnosed diaphragmatic hernia. Am J Med Genet. 2001;103:278–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cannon C, Dildy GA, Ward R, Varner MW, Dudley DJ. A population-based study of congenital diaphragmatic hernia in Utah: 1988–1994. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87:959–963. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(96)00052-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sadler TW. Langman's Medical Embryology. 1990;6:164–178. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moore K, Persaud TVN. The developing human: clinically oriented embryology. 1993;5:174–185. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laxdal OE, McDougall H, Mellin GW. Congenital eventration of the diaphragm. N Engl J Med. 1954;250:401–408. doi: 10.1056/NEJM195403112501001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Michelson E. Eventration of the diaphragm. Surgery. 1961;49:410–422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shah-Mirany J, Schmitz GL, Watson RR. Eventration of the diaphragm. Physiologic and surgical significance. Arch Surg. 1968;96:844–850. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1968.01330230152024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thomas TV. Congenital eventration of the diaphragm. Ann Thorac Surg. 1970;10:180–192. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(10)65584-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dillon E, Renwick M, Wright C. Congenital diaphragmatic herniation: antenatal detection and outcome. Br J Radiol. 2000;73:360–365. doi: 10.1259/bjr.73.868.10844860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Skarsgard ED, Harrison MR. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia: the surgeon's perspective. Pediatr Rev. 1999;20:e71–e78. doi: 10.1542/pir.20-10-e71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moss RL, Chen CM, Harrison MR. Prosthetic patch durability in congenital diaphragmatic hernia: a long-term follow-up study. J Pediatr Surg. 2001;36:152–154. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2001.20037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jaillard SM, Pierrat V, Dubois A, Truffert P, Lequien P, Wurtz AJ, Storme L. Outcome at 2 years of infants with congenital diaphragmatic hernia: a population-based study. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;75:250–256. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(02)04278-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kyzer S, Sirota L, Chaimoff C. Abdominal wall closure with a silastic patch after repair of congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Arch Surg. 2004;139:296–298. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.139.3.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grethel EJ, Cortes RA, Wagner AJ, Clifton MS, Lee H, Farmer DL, Harrison MR, Keller RL, Nobuhara KK. Prosthetic patches for congenital diaphragmatic hernia repair: Surgisis vs Gore-Tex. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41:29–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beck WC, Motsay DS. Eventration of the diaphragm. AMA Arch Surg. 1952;65:557–563. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1952.01260020573008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsugawa C, Kimura K, Nishijima E, Muraji T, Yamaguchi M. Diaphragmatic eventration in infants and children: is conservative treatment justified? J Pediatr Surg. 1997;32:1643–1644. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(97)90473-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yazici M, Karaca I, Arikan A, Erikci V, Etensel B, Temir G, Sencan A, Ural Z, Mutaf O. Congenital eventration of the diaphragm in children: 25 years' experience in three pediatric surgery centers. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2003;13:298–301. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-43573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wayne ER, Campbell JB, Burrington JD, Davis WS. Eventration of the diaphragm. J Pediatr Surg. 1974;9:643–651. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(74)90101-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iliff PJ, Eyre JA, Westaby S, de Leval M, de Sousa C. Neonatal pericardial effusion associated with central eventration of the diaphragm. Arch Dis Child. 1983;58:147–149. doi: 10.1136/adc.58.2.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakayama DK, Harrison MR, Chinn DH, Callen PW, Filly RA, Golbus MS, De Lorimier AA. Prenatal diagnosis and natural history of the fetus with a congenital diaphragmatic hernia: initial clinical experience. J Pediatr Surg. 1985;20:118–124. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(85)80282-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Benacerraf BR, Frigoletto FD., Jr In utero treatment of a fetus with diaphragmatic hernia complicated by hydrops. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1986;155:817–818. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(86)80027-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kelly DR, Grant EG, Zeman RK, Choyke PL, Bolan JC, Warsof SL. In utero diagnosis of congenital diaphragmatic hernia by CT amniography. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1986;10:500–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Calisti A, Manzoni C, Pintus C, Perrelli L. Prenatal diagnosis and management of some fetal intrathoracic abnormalities. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1986;22:61–68. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(86)90090-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Fonseca JM, Davies MR, Bolton KD. Congenital hydropericardium associated with the herniation of part of the liver into the pericardial sac. J Pediatr Surg. 1987;22:851–853. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(87)80653-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blott M, Nicolaides KH, Greenough A. Pleuroamniotic shunting for decompression of fetal pleural effusions. Obstet Gynecol. 1988;71:798–800. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vijayaraghavan SB. Diaphragmatic eventration into the pericardial sac: sonographic diagnosis. J Clin Ultrasound. 1988;16:510–512. doi: 10.1002/jcu.1870160711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hasegawa T, Kamata S, Imura K, Ishikawa S, Okuyama H, Okada A, Chiba Y. Use of lungthorax transverse area ratio in the antenatal evaluation of lung hypoplasia in congenital diaphragmatic hernia. J Clin Ultrasound. 1990;18:705–709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jurcak-Zaleski S, Comstock CH, Kirk JS. Eventration of the diaphragm. Prenatal diagnosis. J Ultrasound Med. 1990;9:351–354. doi: 10.7863/jum.1990.9.6.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thiagarajah S, Abbitt PL, Hogge WA, Leeson SH. Prenatal diagnosis of eventration of the diaphragm. J Clin Ultrasound. 1990;18:46–49. doi: 10.1002/jcu.1870180111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ake E, Fouron JC, Lessard M, Boisvert J, Grignon A, van Doesburg NH. In utero sonographic diagnosis of diaphragmatic hernia with hepatic protrusion into the pericardium mimicking an intrapericardial tumour. Prenat Diagn. 1991;11:719–724. doi: 10.1002/pd.1970110909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bahado-Singh RO, Romero R, Vecchio M, Hobbins JC. Prenatal diagnosis of congenital hiatal hernia. J Ultrasound Med. 1992;11:297–300. doi: 10.7863/jum.1992.11.6.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dillon E, Renwick M. Antenatal detection of congenital diaphragmatic hernias: the northern region experience. Clin Radiol. 1993;48:264–267. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(05)81015-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jelsema RD, Isada NB, Kazzi NJ, Sargent K, Harrison MR, Johnson MP, Evans MI. Prenatal diagnosis of congenital diaphragmatic hernia not amenable to prenatal or neonatal repair: Brachmann-de Lange syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1993;47:1022–1023. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320470717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Narayan H, De Chazal R, Barrow M, McKeever P, Neale E. Familial congenital diaphragmatic hernia: prenatal diagnosis, management, and outcome. Prenat Diagn. 1993;13:893–901. doi: 10.1002/pd.1970131003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gadow EC, Lippold S, Serafin E, Salgado LJ, Garcia C, Prudent L. Prenatal diagnosis and long survival of Fryns' syndrome. Prenat Diagn. 1994;14:673–676. doi: 10.1002/pd.1970140806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.White J, Chan YF, Neuberger S, Wilson T. Prenatal sonographic detection of intraabdominal extralobar pulmonary sequestration: report of three cases and literature review. Prenat Diagn. 1994;14:653–658. doi: 10.1002/pd.1970140802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bollmann R, Kalache K, Mau H, Chaoui R, Tennstedt C. Associated malformations and chromosomal defects in congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Fetal Diagn Ther. 1995;10:52–59. doi: 10.1159/000264193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stringer MD, Goldstein RB, Filly RA, Howell LJ, Sola A, Adzick NS, Harrison MR. Fetal diaphragmatic hernia without visceral herniation. J Pediatr Surg. 1995;30:1264–1266. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(95)90481-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dommergues M, Louis-Sylvestre C, Mandelbrot L, Oury JF, Herlicoviez M, Body G, Gamerre M, Dumez Y. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia: can prenatal ultrasonography predict outcome? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;174:1377–1381. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70688-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hubbard AM, Adzick NS, Crombleholme TM, Haselgrove JC. Left-sided congenital diaphragmatic hernia: value of prenatal MR imaging in preparation for fetal surgery. Radiology. 1997;203:636–640. doi: 10.1148/radiology.203.3.9169681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lau TK, Fung HY, Fung TY. Fetal diaphragmatic hernia presented with transient unilateral pleural effusion. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1997;9:125–127. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.1997.09020125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sebire NJ, Snijders RJ, Davenport M, Greenough A, Nicolaides KH. Fetal nuchal translucency thickness at 10–14 weeks' gestation and congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90:943–946. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(97)89686-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ssemakula N, Stewart DL, Goldsmith LJ, Cook LN, Bond SJ. Survival of patients with congenital diaphragmatic hernia during the ECMO era: an 11-year experience. J Pediatr Surg. 1997;32:1683–1689. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(97)90506-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Teixeira J, Sepulveda W, Hassan J, Cox PM, Singh MP. Abdominal circumference in fetuses with congenital diaphragmatic hernia: correlation with hernia content and pregnancy outcome. J Ultrasound Med. 1997;16:407–410. doi: 10.7863/jum.1997.16.6.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thebaud B, Azancot A, de Lagausie P, Vuillard E, Ferkadji L, Benali K, Beaufils F. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia: antenatal prognostic factors. Does cardiac ventricular disproportion in utero predict outcome and pulmonary hypoplasia? Intensive Care Med. 1997;23:10062–10069. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chacko J, Ford WD, Furness ME. Antenatal detection of hiatus hernia. Pediatr Surg Int. 1998;13:163–164. doi: 10.1007/s003830050276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Geary MP, Chitty LS, Morrison JJ, Wright V, Pierro A, Rodeck CH. Perinatal outcome and prognostic factors in prenatally diagnosed congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1998;12:107–111. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.1998.12020107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bahlmann F, Merz E, Hallermann C, Stopfkuchen H, Kramer W, Hofmann M. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia: ultrasonic measurement of fetal lungs to predict pulmonary hypoplasia. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1999;14:162–168. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.1999.14030162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brackley KJ, Kilby MD, Morton J, Whittle MJ, Knight SJ, Flint J. A case of recurrent congenital fetal anomalies associated with a familial subtelomeric translocation. Prenat Diagn. 1999;19:570–574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Urban BA, Duhl AJ, Ural SH, Blakemore KJ, Fishman EK. Helical CT amniography of congenital diaphragmatic hernia. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999;172:809–812. doi: 10.2214/ajr.172.3.10063887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Noimark L, Sellwood M, Wyatt J, Yates R. Transposition of the great arteries, ventricular septal defect and diaphragmatic hernia in a fetus: the role of prenatal diagnosis in helping to predict postnatal survival. Prenat Diagn. 2000;20:924–926. doi: 10.1002/1097-0223(200011)20:11<924::aid-pd946>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Paek BW, Danzer E, Machin GA, Coakley F, Albanese CT, Filly RA. Prenatal diagnosis of bilateral diaphragmatic hernia: diagnostic pitfalls. J Ultrasound Med. 2000;19:495–500. doi: 10.7863/jum.2000.19.7.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tazuke Y, Kawahara H, Soh H, Yoneda A, Yagi M, Imura K, Sumi K, Nobunaga M. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia in identical twins. Pediatr Surg Int. 2000;16:512–514. doi: 10.1007/s003839900324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Danzer E, Paek BW, Farmer DL, Poulain FR, Farrell JA, Harrison MR, Albanese CT. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia associated with a gastroesophageal duplication cyst: a case report. J Pediatr Surg. 2001;36:626–628. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2001.22304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Detti L, Mari G, Ferguson JE. Color Doppler ultrasonography of the superior mesenteric artery for prenatal ultrasonographic diagnosis of a left-sided congenital diaphragmatic hernia. J Ultrasound Med. 2001;20:689–692. doi: 10.7863/jum.2001.20.6.689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mahieu-Caputo D, Sonigo P, Dommergues M, Fournet JC, Thalabard JC, Abarca C, Benachi A, Brunelle F, Dumez Y. Fetal lung volume measurement by magnetic resonance imaging in congenital diaphragmatic hernia. BJOG. 2001;108:863–868. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2001.00184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Masturzo B, Kalache KD, Cockell A, Pierro A, Rodeck CH. Prenatal diagnosis of an ectopic intrathoracic kidney in right-sided congenital diaphragmatic hernia using color Doppler ultrasonography. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2001;18:173–174. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.2001.00411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ogunyemi D. Serial sonographic findings in a fetus with congenital hiatal hernia. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2001;17:350–353. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.2001.00366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Song MS, Yoo SJ, Smallhorn JF, Mullen JB, Ryan G, Hornberger LK. Bilateral congenital diaphragmatic hernia: diagnostic clues at fetal sonography. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2001;17:255–258. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.2001.00348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tsukahara Y, Ohno Y, Itakura A, Mizutani S. Prenatal diagnosis of congenital diaphragmatic eventration by magnetic resonance imaging. Am J Perinatol. 2001;18:241–244. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-16992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Betremieux P, Lionnais S, Beuchee A, Pladys P, Le Bouar G, Pasquier L, Loeuillet-Olivo L, Azzis O, Milon J, Wodey E, Fremond B, Odent S, Poulain P. Perinatal management and outcome of prenatally diagnosed congenital diaphragmatic hernia: a 1995–2000 series in Rennes University Hospital. Prenat Diagn. 2002;22:988–994. doi: 10.1002/pd.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hyodo H, Nitsu T, Yoshizawa K, Unno N, Aoki T, Taketani Y. A case of a fetus with gastric perforation associated with congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2002;20:518–519. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.2002.00849_2.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ikeda K, Hokuto I, Tokieda K, Nishimura O, Ishimoto H, Morikawa Y. A congenital anterior diaphragmatic hernia with massive pericardial effusion requiring neither emergency pericardiocentesis nor operation. A case report and review of the literature. J Perinat Med. 2002;30:336–340. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2002.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sydorak RM, Goldstein R, Hirose S, Tsao K, Farmer DL, Lee H, Harrison MR, Albanese CT. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia and hydrops: a lethal association? J Pediatr Surg. 2002;37:1678–1680. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2002.36691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Vettraino IM, Lee W, Comstock CH. The evolving appearance of a congenital diaphragmatic hernia. J Ultrasound Med. 2002;21:85–89. doi: 10.7863/jum.2002.21.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Laudy JA, Van Gucht M, Van Dooren MF, Wladimiroff JW, Tibboel D. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia: an evaluation of the prognostic value of the lung-to-head ratio and other prenatal parameters. Prenat Diagn. 2003;23:634–639. doi: 10.1002/pd.654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lee R, Mendeloff EN, Huddleston C, Sweet SC, de la MM. Bilateral lung transplantation for pulmonary hypoplasia caused by congenital diaphragmatic hernia. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;126:295–297. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5223(03)00202-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Robnett-Filly B, Goldstein RB, Sampior D, Hom M. Morgagni hernia: a rare form of congenital diaphragmatic hernia. J Ultrasound Med. 2003;22:537–539. doi: 10.7863/jum.2003.22.5.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yang JI. Left diaphragmatic eventration diagnosed as congenital diaphragmatic hernia by prenatal sonography. J Clin Ultrasound. 2003;31:214–217. doi: 10.1002/jcu.10157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Varlet F, Bousquet F, Clemenson A, Chauleur C, Kopp-Dutour N, Tronchet M, Teyssier G, Prieur F, Varlet MN. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Two cases with early prenatal diagnosis and increased nuchal translucency. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2003;18:33–35. doi: 10.1159/000066381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chen CP, Chern SR, Cheng SJ, Chang TY, Yeh LF, Lee CC, Pan CW, Wang W, Tzen CY. Second-trimester diagnosis of complete trisomy 9 associated with abnormal maternal serum screen results, open sacral spina bifida and congenital diaphragmatic hernia, and review of the literature. Prenat Diagn. 2004;24:455–462. doi: 10.1002/pd.900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hedrick HL, Crombleholme TM, Flake AW, Nance ML, von Allmen D, Howell LJ, Johnson MP, Wilson RD, Adzick NS. Right congenital diaphragmatic hernia: Prenatal assessment and outcome. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39:319–323. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2003.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ruano R, Benachi A, Aubry MC, Bernard JP, Hameury F, Nihoul-Fekete C, Dumez Y. Prenatal sonographic diagnosis of congenital hiatal hernia. Prenat Diagn. 2004;24:26–30. doi: 10.1002/pd.772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ruano R, Benachi A, Joubin L, Aubry MC, Thalabard JC, Dumez Y, Dommergues M. Three-dimensional ultrasonographic assessment of fetal lung volume as prognostic factor in isolated congenital diaphragmatic hernia. BJOG. 2004;111:423–429. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Jacquemyn Y, Op dB, Van Overmeire B, Vaneerdeweg W. Right-sided anterior congenital diaphragmatic hernia: prenatal diagnosis with magnetic resonance imaging. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2005;84:916–917. doi: 10.1111/j.0001-6349.2005.0414a.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.St Peter SD, Shah SR, Little DC, Calkins CM, Sharp RJ, Ostlie DJ. Bilateral congenital diaphragmatic hernia with absent pleura and pericardium. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2005;73:624–627. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yang CK, Shih JC, Hsu WM, Peng SS, Shyu MK, Lee CN, Hsieh FJ. Isolated right diaphragmatic eventration mimicking congenital heart disease in utero. Prenat Diagn. 2005;25:872–875. doi: 10.1002/pd.1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Poole CA, Rowe MI, Fojaco RM, Wexler HA. Congenital eventration of the septum transversum: a rare form of congenital diaphragmatic anomaly. Pediatr Radiol. 1976;4:257–260. doi: 10.1007/BF02461536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Cantrell JR, Haller JA, Ravitch MM. A syndrome of congenital defects involving the abdominal wall, sternum, diaphragm, pericardium, and heart. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1958;107:602–614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Yuan W, Rao Y, Babiuk RP, Greer JJ, Wu JY, Ornitz DM. A genetic model for a central (septum transversum) congenital diaphragmatic hernia in mice lacking Slit3. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:5217–5222. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0730709100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Van Meurs K, Lou SB. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia: the neonatologist's perspective. Pediatr Rev. 1999;20:e79–e87. doi: 10.1542/pir.20-10-e79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kimura K, Tsugawa C, Matsumoto Y, Soper R. Use of pledget in the repair of diaphragmatic anomalies. J Pediatr Surg. 1991;26:84–86. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(91)90434-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.de Vries TS, Koens BL, Vos A. Surgical treatment of diaphragmatic eventration caused by phrenic nerve injury in the newborn. J Pediatr Surg. 1998;33:602–605. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(98)90325-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Schwartz MZ, Filler RM. Plication of the diaphragm for symptomatic phrenic nerve paralysis. J Pediatr Surg. 1978;13:259–263. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(78)80397-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Clark RH, Hardin WD, Jr, Hirschl RB, Jaksic T, Lally KP, Langham MR, Jr, Wilson JM. Current surgical management of congenital diaphragmatic hernia: a report from the Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia Study Group. J Pediatr Surg. 1998;33:1004–1009. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(98)90522-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Skari H, Bjornland K, Frenckner B, Friberg LG, Heikkinen M, Hurme T, Loe B, Mollerlokken G, Nielsen OH, Qvist N, Rintala R, Sandgren K, Wester T, Emblem R. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia in Scandinavia from 1995 to 1998: Predictors of mortality. J Pediatr Surg. 2002;37:1269–1275. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2002.34980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Einzig S, Munson DP, Singh S, Castaneda-Zuniga W, Amplatz K. Intrapericardial herniation of the liver: uncommon cause of massive pericardial effusion in neonates. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1981;137:1075–1077. doi: 10.2214/ajr.137.5.1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Blank E, Campbell JR. Congenital posterolateral defect in the right side of the diaphragm. Pediatrics. 1976;57:807–810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Chilton HW, Chang JH, Jones MD, Jr, Brooks JG. Right-sided congenital diaphragmatic herniae presenting as pleural effusions in the newborn: dangers and pitfalls. Arch Dis Child. 1978;53:600–603. doi: 10.1136/adc.53.7.600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Murray MJ, Brain JL, Ahluwalia JS. Neonatal pleural effusion and insertion of intercostal drain into the liver. J R Soc Med. 2005;98:319–320. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.98.7.319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Louie HW, Martin SM, Mulder DG. Pulmonary sequestration: 17-year experience at UCLA. Am Surg. 1993;59:801–805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Levine D, Barnewolt CE, Mehta TS, Trop I, Estroff J, Wong G. Fetal thoracic abnormalities: MR imaging. Radiology. 2003;228:379–388. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2282020604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]