Abstract

MenBvac and MeNZB are safe and efficacious vaccines against serogroup B meningococcal disease. MenBvac is prepared from a B:15:P1.7,16 meningococcal strain (strain 44/76), and MeNZB is prepared from a B:4:P1.7-2,4 strain (strain NZ98/254). At 6-week intervals, healthy adults received three doses of MenBvac (25 μg), MeNZB (25 μg), or the MenBvac and MeNZB (doses of 12.5 μg of each vaccine) vaccines combined, followed by a booster 1 year later. Two-thirds of the subjects who received a monovalent vaccine in the primary schedule received the other monovalent vaccine as a booster dose. The immune responses to the combined vaccine were of the same magnitude as the homologous responses to each individual vaccine observed. At 6 weeks after the third dose, 77% and 87% of the subjects in the combined vaccine group achieved serum bactericidal titers of ≥4 against strains 44/76 and NZ98/254, respectively, and 97% and 93% of the subjects achieved a fourfold or greater increase in opsonophagocytic activity against strains 44/76 and NZ98/254, respectively. For both strains, a trend of higher responses after the booster dose was observed in all groups receiving at least one dose of the respective strain-specific vaccine. Local and systemic reactions were common in all vaccine groups. Most reactions were mild or moderate in intensity, and there were no vaccine-related serious adverse events. The safety profile of the combined vaccine was not different from those of the separate monovalent vaccines. In conclusion, use of either of the single vaccines or the combination of MenBvac and MeNZB may have a considerable impact on the serogroup B meningococcal disease situation in many countries.

Candidate vaccines against Neisseria meningitidis serogroup B are usually based on outer membrane proteins because the capsular polysaccharide from serogroup B meningococci is poorly immunogenic (31). These vaccines mainly induce strain-specific antibodies, particularly in infants (26). Outer membrane vesicle (OMV) vaccines prepared from the epidemic strain have been shown to be efficacious in the control of clonal serogroup B epidemics (14, 25, 27).

The OMV vaccine MenBvac was developed on the basis of a strain (strain B:15:P1.7,16) representative of the epidemic of serogroup B meningococcal disease that started in Norway in the mid-1970s. This vaccine has been shown to be safe and immunogenic and to confer protection (2, 8, 18, 19). A similar meningococcal serogroup B OMV vaccine based on a B:4:P1.7-2,4 strain was introduced to control the ongoing meningococcal epidemic in New Zealand (7, 20, 24). However, in most countries with a high incidence of serogroup B meningococcal disease, several different clones are responsible for the cases. Ideally, therefore, a serogroup B meningococcal vaccine should elicit protection against a wide range of clinical strains in all age groups. The two most prevalent serogroup B strains in Europe in 1999/2000 were B:4:P1.4 and B:15:P1.7,16, together being responsible for about 75% of the cases of serogroup B meningococcal disease in Europe (5, 17, 29). Therefore, the approach of combining two different OMV vaccines, MenBvac and MeNZB, may have a considerable impact on the control of serogroup B meningococcal disease (2, 21, 27).

Preclinical studies with mice had suggested that half the normal antigen dose of each vaccine could elicit immune responses similar to those elicited by full doses of the individual vaccines when they are administered in combination (16) and that sequential immunization with OMVs from heterologous strains could elicit broadly protective serum antibodies against serogroup B strains (15).

When the same total amount of protein antigen and adjuvant (aluminum hydroxide) as in the monovalent vaccines is used, the safety profile of the vaccine combination was expected to be similar to those of the individual vaccines, which have both been shown to be safe and well tolerated (2, 19, 27).

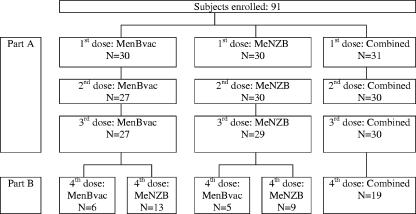

The aims of this study were to evaluate the safety and immunogenicity of (i) a combination of MenBvac and MeNZB (with half the antigen dose of each vaccine given in the same syringe) compared with those of MenBvac or MeNZB given separately in a primary schedule and (ii) a booster dose of the combined vaccine or either of the two individual monovalent vaccines (the same vaccine as given in the primary three-dose schedule or the other monovalent vaccine) (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Subject disposition flowchart for the primary immunization schedule (part A) and the booster dose (part B). The numbers of subjects (N) receiving the different vaccines are presented by dose. The subjects in this study received one of the following schedules: four doses of combined vaccine (MenBvac [12.5 μg] plus MeNZB [12.5 μg]), four doses of MenBvac (25 μg), four doses of MeNZB (25 μg), three doses of MenBvac (25 μg) plus one dose of MeNZB (25 μg), or three doses of MeNZB (25 μg) plus one dose of MenBvac (25 μg).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Vaccines.

MenBvac was manufactured at NIPH from a B:15:P1.7,16 meningococcal strain (strain 44/76) by growth in a fermentor and extraction of the OMVs with the detergent deoxycholate. The OMVs were purified by fractionated centrifugation and adsorbed to aluminum hydroxide (9). MeNZB was prepared at NIPH by a similar technique from a B:4:P1.7-2,4 meningococcal strain (strain NZ98/254) (11). This strain was kindly provided by Diana Martin of the Institute of Environmental Science and Research, Porirua, New Zealand.

One dose (0.5 ml) of either MenBvac or MeNZB contained 25 μg outer membrane protein and 1.67 mg aluminum hydroxide (corresponding to 0.57 mg aluminum).

The combination vaccine was prepared by mixing MenBvac and MeNZB immediately before injection. One dose (0.5 ml) of the combination vaccine contained MenBvac (12.5 μg) and MeNZB (12.5 μg) and the same amount of aluminum hydroxide as either of the two separate monovalent vaccines.

Vaccinees.

Healthy adults who had given written informed consent prior to study entry and who fulfilled all inclusion criteria and none of the exclusion criteria (e.g., pregnancy, chronic disease, previously having received a meningococcal B vaccine of any kind, and the previous occurrence of disease caused by N. meningitidis) were eligible for participation in the study. The subjects were mainly recruited among students in Oslo, Norway.

Administration.

Three primary vaccine doses were administered at weeks 0, 6, and 12; and a booster dose was administered 1 year later. In the primary schedule (part A), the subjects were randomly assigned 1:1:1 to receive either the combined MenBvac-MeNZB vaccine, MenBvac only, or MeNZB only. For the booster dose (part B), subjects receiving MenBvac or MeNZB alone in the primary three-dose schedule were randomized in a 1:2 ratio to receive either the same monovalent vaccine used in the primary schedule or the other monovalent vaccine (crossover schedule), while all subjects receiving the combined vaccine within the primary schedule also received the combined vaccine as a booster (Fig. 1). The vaccines were administered intramuscularly in the deltoid region of the nondominant arm.

Immunogenicity.

Blood samples collected at several time points during the study were fractionated, and the serum was aliquoted and stored at −20°C. Blood samples obtained on the day of each vaccination and approximately 6 weeks thereafter were analyzed by the serum bactericidal assay (SBA) and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Opsonophagocytic activity (OPA) was assessed in sera taken at the time of the first dose and 6 weeks after the third and fourth vaccine doses.

SBA.

SBA is a functional assay that measures the ability of serum antibodies to induce the lysis of bacteria in the presence of complement.

The analyses were performed in microtiter plates by the “tilt” method (3). After heat inactivation, the sera to be tested were serially diluted twofold (starting at 1:2) and were incubated for 60 min (37°C) in the presence of the bacterial inoculum (time zero samples) and human complement (25% human serum from one donor without bactericidal activity). The bacterial colonies were counted by using a colony counter (Sorcerer; Perceptive Instruments, Haverhill, Suffolk, United Kingdom), and the bactericidal titer was defined as the reciprocal of the serum dilution that killed at least 50% of the organisms. The bactericidal activities against strain 44/76 (B:15:P1.7,16) and strain NZ98/254 (B:4:P1.7-2,4) were measured for all subjects.

Opsonophagocytosis.

Sera (twofold dilutions starting at 1:2) were assessed for their OPAs against live bacteria of the two vaccine strains (strains 44/76 and NZ98/254) by a respiratory burst assay using flow cytometry (1, 13).

ELISA.

Immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies against serogroup B OMV antigens of both strains were analyzed by ELISA. The OMV ELISA was performed as described by Rosenqvist et al. (22). The antigens used to coat the ELISA microtiter plates were OMVs from strain 44/76 and strain NZ98/254, prepared as for vaccine production. The results are given as arbitrary units per ml (U/ml).

Safety monitoring.

The subjects were monitored for selected local and systemic adverse events after each dose. These events were termed “local and systemic reactions,” irrespective of their relation to the study vaccine. The subjects completed a diary card to record local reactions (i.e., erythema, swelling, induration, and pain at the injection site), systemic reactions (i.e., nausea, malaise, myalgia, arthralgia, and headache), and body temperature for 7 days following each vaccination, including the day of injection. Local and systemic reactions persisting after the first week and all other adverse events were recorded at the planned visits, while all serious adverse events were collected throughout the study.

Ethics.

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the International Conference on Harmonization guideline for good clinical practice, and other national legal and regulatory requirements. The trial was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics and the Norwegian Medicines Agency. All subjects signed informed consent before any trial activities were performed.

Statistical methods.

SBA geometric mean titers (GMTs) against the two vaccine strains (strains 44/76 and NZ98/254) and OPA GMTs against the two vaccine strains and the associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were computed for each vaccine group from a one-way analysis of variance.

The proportion of subjects with an SBA titer or an OPA titer of at least 4 (1:4 serum dilution) against the two vaccine strains and the associated 95% CIs were also computed for each vaccine group from a one-way analysis of variance.

Also the proportion of responders, defined as subjects showing a fourfold or greater increase in bactericidal activity from the baseline (to a minimum titer of ≥1:4), to the different meningococcal strains and the associated 95% Clopper-Pearson CIs were calculated. The differences between the vaccine groups were obtained by use of a categorical linear model.

The IgG antibody responses, measured by ELISA as the geometric mean concentration (GMC) against OMV antigens from both vaccines, are presented with the associated 95% CIs and were determined by use of the same methods described above.

All analyses were performed by using SAS software (version 8.2 or higher).

All demography and safety analyses were run descriptively.

RESULTS

A total of 91 subjects were given at least one vaccine dose: 31 in the combination group, 30 in the MenBvac group, and 30 in the MeNZB group (Fig. 1). The treatment groups were similar regarding age, sex, and ethnic origin. The mean age at the time of inclusion was 23 years in all three groups, and the age range was from 19 to 35 years. In all groups a majority of the participants were females (70% in the MenBvac group, 80% in the MeNZB group, and 90% in the combined group), and the majority of the subjects were of Caucasian origin (84% in the combined group and 87% in the other two groups). Fifty-two subjects were available for the booster vaccination after 1 year.

Immunogenicity. (i) Part A, primary immunization schedule. (a) SBA.

A gradual increase in SBA titers against both strain 44/76 and strain NZ98/254 was observed after each dose in all vaccine groups (Table 1). The largest increase in the GMT against strain 44/76 was observed in the MenBvac group, in which the GMT amounted to 13 at 6 weeks after the third dose; and the largest increase against strain NZ98/254 was observed in the MeNZB group, with a GMT of 8.4 at 6 weeks after the third dose (Table 1). However, the differences between the vaccine groups were not statistically significant for any of the strains.

TABLE 1.

Primary immunization schedule, SBA GMTs, and percentages of subjects with SBA titers of ≥4 against strains 44/76 and NZ98/254a

| Time pointb | Strain | Vaccine group | No. of subjects | % Subjects with SBA titers of ≥4 (95% CI) | GMT (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 44/76 | MenBvac | 24 | 25 (10-47) | 2.0 (1.29-3.11) |

| 44/76 | MeNZB | 27 | 22 (9-42) | 1.8 (1.2-2.7) | |

| 44/76 | Combined | 30 | 13 (4-31) | 1.6 (1.0-2.3) | |

| NZ98/254 | MenBvac | 24 | 29 (13-51) | 2.1 (1.4-3.0) | |

| NZ98/254 | MeNZB | 27 | 15 (4-34) | 1.5 (1.1-2.2) | |

| NZ98/254 | Combined | 30 | 17 (6-35) | 1.6 (1.1-2.2) | |

| 6 wk after first dose | 44/76 | MenBvac | 24 | 63 (41-81) | 6.7 (3.8-12) |

| 44/76 | MeNZB | 27 | 56 (35-75) | 4.2 (2.5-7.2) | |

| 44/76 | Combined | 29 | 55 (36-74) | 4.0 (2.4-6.7) | |

| NZ98/254 | MenBvac | 24 | 67 (45-84) | 4.0 (2.5-6.4) | |

| NZ98/254 | MeNZB | 27 | 56 (35-75) | 4.2 (2.7-6.6) | |

| NZ98/254 | Combined | 29 | 55 (36-74) | 3.7 (2.4-5.7) | |

| 6 wk after second dose | 44/76 | MenBvac | 23 | 65 (43-84) | 10 (5.7-19) |

| 44/76 | MeNZB | 25 | 56 (35-76) | 5.0 (2.8-8.9) | |

| 44/76 | Combined | 30 | 70 (51-85) | 5.3 (3.1-9.0) | |

| NZ98/254 | MenBvac | 23 | 61 (39-80) | 4.5 (2.8-7.4) | |

| NZ98/254 | MeNZB | 25 | 80 (59-93) | 7.4 (4.6-12) | |

| NZ98/254 | Combined | 30 | 70 (51-85) | 4.9 (3.2-7.6) | |

| 6 wk after third dose | 44/76 | MenBvac | 23 | 78 (56-93) | 13 (6.8-25) |

| 44/76 | MeNZB | 26 | 58 (37-77) | 5.7 (3.1-10) | |

| 44/76 | Combined | 30 | 77 (58-90) | 8.98 (5.1-16) | |

| NZ98/254 | MenBvac | 23 | 65 (43-84) | 4.9 (3.1-8.0) | |

| NZ98/254 | MeNZB | 26 | 81 (61-93) | 8.4 (5.4-13) | |

| NZ98/254 | Combined | 30 | 87 (69-96) | 7.8 (5.1-12) |

Strain 44/76 is of clonal complex ST-32, and strain NZ98/254 is of clonal complex ST-41/44.

Measurements were taken prior to vaccination (baseline) and 6 weeks after each dose was administered.

At the baseline, the proportions of subjects with SBA titers of ≥4 against strain 44/76 ranged from 13% to 25%. These proportions increased to 78% in the MenBvac group, 77% in the combined group, and 58% in the MeNZB group at 6 weeks after the third dose (Table 1). The proportions of responders to strain 44/76 were similar in the MenBvac group (52%; 95% CI, 31 to 73%) and the combined group (53%; 95% CI, 34 to 72%) at 6 weeks after the third dose, while it was lower in the MeNZB group (heterologous strain) (38%; 95% CI, 20 to 59%).

At the baseline, the proportions of subjects with SBA titers of ≥4 against strain NZ98/254 ranged from 15% to 29%. At 6 weeks after the third dose the proportions of subjects with SBA titers of ≥4 reached 81% in the MeNZB group and 87% in the combined group. In the MenBvac group, the proportion of subjects with SBA titers of ≥4 against this heterologous strain was 65% (Table 1). The proportions of responders to strain NZ98/254 were similar in the MeNZB group (50%; 95% CI, 30 to 70%) and the combined group (53%; 95% CI, 34 to 72%) at 6 weeks after the third dose, while it was lower in the MenBvac group (heterologous strain) (30%; 95% CI, 13 to 53%).

However, the differences in the immune responses between the vaccine groups were not statistically significant for any of the two strains.

(b) Opsonophagocytosis.

The highest increase in the mean OPA GMT against strain 44/76 at 6 weeks after the third dose was observed in the MenBvac group, while the highest increase in the OPA GMTs against strain NZ98/254 was observed in the combined group (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Primary immunization schedule and opsonophagocytic GMTs against strains 44/76 and NZ98/254

| Time point | Strain | Vaccine group | No. of subjects | OPA GMT (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 44/76 | MenBvac | 25 | 3.9 (2.1-7.3) |

| 44/76 | MeNZB | 30 | 5.2 (2.9-9.1) | |

| 44/76 | Combined | 30 | 4.6 (2.6-8.1) | |

| NZ98/254 | MenBvac | 25 | 3.0 (1.7-5.1) | |

| NZ98/254 | MeNZB | 30 | 2.6 (1.6-4.3) | |

| NZ98/254 | Combined | 30 | 2.3 (1.4-81) | |

| 6 wk after | 44/76 | MenBvac | 25 | 139 (88-221) |

| third dose | 44/76 | MeNZB | 28 | 46 (30-72) |

| 44/76 | Combined | 30 | 106 (70-162) | |

| NZ98/254 | MenBvac | 25 | 61 (38-96) | |

| NZ98/254 | MeNZB | 28 | 69 (45-107) | |

| NZ98/254 | Combined | 30 | 83 (54-126) |

The proportions of subjects with a fourfold or greater increase in the OPA titer against strain 44/76 were high in all vaccine groups and amounted to 96% in the MenBvac group, 82% in the MeNZB group, and 97% in the combined group. The proportions of subjects with a fourfold or greater increase in the OPA titer against strain NZ98/254 were also high and amounted to 100% in the MeNZB group, 88% in the MenBvac group, and 93% in the combined group.

(c) ELISA IgG antibodies.

At the baseline, the GMCs of IgG antibodies against OMV antigens were similar in the three vaccine groups. A gradual increase in GMCs was observed after each dose in all vaccine groups. For OMVs from strain 44/76, the largest increase in the GMC at 6 weeks after the third dose was observed in the MenBvac group (Table 3). For OMVs from strain NZ98/254, the largest increase in the GMC of IgG was observed in the combined group (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Primary immunization schedule and ELISA IgG GMCs against OMVs from strains 44/76 and NZ98/254

| Time point | Strain | Vaccine group | No. of subjects | IgG GMC (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 44/76 | MenBvac | 25 | 73 (51-105) |

| 44/76 | MeNZB | 30 | 75 (54-104) | |

| 44/76 | Combined | 30 | 66 (48-92) | |

| NZ98/254 | MenBvac | 25 | 73 (51-105) | |

| NZ98/254 | MeNZB | 30 | 70 (50-98) | |

| NZ98/254 | Combined | 30 | 62 (44-86) | |

| 6 wk after first | 44/76 | MenBvac | 25 | 317 (219-459) |

| dose | 44/76 | MeNZB | 30 | 185 (132-260) |

| 44/76 | Combined | 30 | 219 (156-307) | |

| NZ98/254 | MenBvac | 25 | 203 (140-294) | |

| NZ98/254 | MeNZB | 30 | 239 (170-334) | |

| NZ98/254 | Combined | 30 | 186 (132-260) | |

| 6 wk after | 44/76 | MenBvac | 25 | 687 (495-953) |

| second dose | 44/76 | MeNZB | 28 | 320 (235-436) |

| 44/76 | Combined | 30 | 400 (297-540) | |

| NZ98/254 | MenBvac | 25 | 364 (255-519) | |

| NZ98/254 | MeNZB | 28 | 459 (328-642) | |

| NZ98/254 | Combined | 30 | 368 (266-509) | |

| 6 wk after | 44/76 | MenBvac | 25 | 1,031 (753-1,412) |

| third dose | 44/76 | MeNZB | 28 | 414 (308-557) |

| 44/76 | Combined | 30 | 687 (516-915) | |

| NZ98/254 | MenBvac | 25 | 530 (377-745) | |

| NZ98/254 | MeNZB | 28 | 601 (436-830) | |

| NZ98/254 | Combined | 30 | 676 (495-922) |

(ii) Part B, booster dose. (a) SBA.

The highest SBA GMTs against strain 44/76 at 6 weeks after the booster dose were observed in the group receiving three doses of MenBvac plus one dose of MeNZB and in the group receiving three doses of MeNZB plus one dose of MenBvac. After the booster dose the proportions of subjects with SBA titers of ≥4 against strain 44/76 ranged from 67% in the group receiving three doses of MeNZB plus one dose of MenBvac to 85% in the group receiving three doses of MenBvac plus one dose of MeNZB group (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

SBA GMTs, percentage of subjects with SBA titers of ≥4, ELISA IgG GMCs against OMVs and opsonophagocytic GMTs, against strain 44/76 before and after a booster dose

| Regimen | No. of subjects

|

SBA GMT (95% CI)

|

% Subjects with SBA titers of ≥4 (95% CI)

|

ELISA GMC (U/ml [95% CI])

|

Opsonophagocytic GMT (95% CI)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before fourth dose | 6 wk after fourth dose | Before fourth dose | 6 wk after fourth dosea | Before fourth dose | 6 wk after fourth dose | Before fourth dose | 6 wk after fourth dose | Before fourth dose | 6 wk after fourth dose | |

| Four doses MenBvac | 6 | 6 | 2.8 (0.98-8.2) | 11 (3.1-42) | 50 (12-88) | 83 (36-100) | 295 (145-600) | 1,625 (889-2,968) | 7.1 (1.9-26) | 81 (34-191) |

| Three doses MenBvac + one dose MeNZB | 13 | 13 | 4.5 (2.2-9.2) | 19 (7.7-46) | 62 (32-86) | 85 (55-98) | 358 (221-581) | 1,323 (879-1,993) | 17 (6.9-41) | 103 (58-186) |

| Four doses MeNZB | 5 | 5 | 5.3 (1.7-17) | 11 (2.5-44) | 60 (15-95) | 80 (28-99) | 339 (156-740) | 819 (423-1,584) | 21 (5.0-89) | 56 (22-143) |

| Three doses MeNZB + one dose MenBvac | 9 | 9 | 4.7 (2.0-11) | 19 (6.4-54) | 56 (21-86) | 67 (30-93) | 229 (128-410) | 1,851 (1,132-3,028) | 5.0 (1.7-15) | 75 (37-151) |

| Four doses combined vaccine | 19 | 19 | 2.4 (1.3-4.4) | 7.2 (3.4-15) | 42 (20-67) | 68 (43-87) | 343 (230-512) | 1,247 (889-1,749) | 10 (4.9-22) | 66 (41-108) |

The fourth dose was given as booster dose 1 year after the primary vaccination.

The highest SBA GMT against strain NZ98/254 at 6 weeks after the booster dose was observed in the group receiving three doses of MenBvac plus one dose of MeNZB. After the booster dose the proportions of subjects with SBA titers of ≥4 ranged from 67% in the four doses of MenBvac group to 89% in the combined group (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

SBA GMTs, percentage of subjects with SBA titers of ≥4 and ELISA IgG GMCs against OMVs and opsonophagocytic GMTs against strain NZ98/254 before and after a booster dose

| Regimen | No. of subjects

|

SBA GMT (95% CI)

|

% Subjects with SBA titers of ≥4 (95% CI)

|

ELISA GMC (U/ml [95% CI])

|

Opsonophagocytic GMT (95% CI)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before fourth dose | 6 wk after fourth dose | Before fourth dosea | 6 wk after fourth dose | Before fourth dose | 6 wk after fourth dose | Before fourth dose | 6 wk after fourth dose | Before fourth dose | 6 wk after fourth dose | |

| Four doses MenBvac | 6 | 6 | 2.5 (0.99-6.4) | 4.0 (1.3-12) | 50 (12-88) | 67 (22-96) | 148 (70-314) | 647 (360-1,162) | 4.5 (1.2-17) | 18 (7.3-44) |

| Three doses MenBvac + one dose MeNZB | 13 | 13 | 4.0 (2.1-7.6) | 20 (9.3-42) | 46 (19-75) | 85 (55-98) | 275 (165-458) | 1480 (994-2,204) | 11 (4.5-27) | 68 (37-124) |

| Four doses MeNZB | 5 | 5 | 3.5 (1.3-9.7) | 11 (3.1-36) | 40 (5-85) | 80 (28-99) | 214 (94-487) | 1,062 (559-2,018) | 11 (2.5-45) | 56 (21-149) |

| Three doses MeNZB + one dose MenBvac | 9 | 9 | 4.0 (1.9-8.6) | 14 (5.5-34) | 44 (14-79) | 78 (40-97) | 216 (117-398) | 1,954 (1,211-3,154) | 6.4 (2.2-19) | 81 (39-168) |

| Four doses combined vaccine | 19 | 19 | 2.1 (1.2-3.5) | 10 (5.5-19) | 26 (9-51) | 89 (67-99) | 271 (177-413) | 1,319 (949-1,833) | 8.3 (3.9-17) | 59 (36-98) |

The fourth dose was given as booster dose 1 year after the primary vaccination.

The SBA responses tended to be higher in the groups receiving at least one dose of homologous or combined vaccine, but the low number of subjects in each treatment group does not allow for any definite conclusions.

(b) Opsonophagocytosis.

The highest mean OPA GMTs against strain 44/76 at 6 weeks after the booster dose were observed in the group receiving three doses of MenBvac plus one dose of MeNZB (Table 4). The highest mean OPA GMTs against strain NZ98/254 at this time point were observed in the group receiving three doses of MeNZB plus one dose of MenBvac (Table 5).

In this study the OPA booster responses were highest in the groups receiving at least one dose of the respective strain-specific vaccine or the combined vaccine.

(c) ELISA IgG antibodies.

At 6 weeks after the booster dose, the highest GMCs of IgG against OMVs from both strain 44/76 and strain NZ98/254 were observed in the group receiving three doses of MeNZB plus one dose of MenBvac (Tables 4 and 5).

The results indicate that the ELISA IgG titers against OMVs were highest in the groups receiving at least one dose of the strain-specific vaccine or the combined vaccine.

Safety.

No serious adverse events occurred in the study, and no adverse events led to a subject's withdrawal from the study.

Local (injection site) reactions.

Pain at the injection site was the most commonly reported local reaction both within the primary immunization schedule and after the booster dose and was reported by all or all but one or two subjects in all vaccine groups. The severity profiles for pain at the injection site were similar between the vaccination groups, with most pain at the injection site reported as either mild or moderate. Severe pain was reported by 23% of the subjects or less after each dose in all vaccine groups.

Induration at the injection site was the second most frequent local reaction both within the primary immunization schedule and after the booster dose and was reported by 30% of the subjects or less after each dose. Severe induration (diameter, >50 mm) was reported by two subjects (11%) or less after each dose in all vaccine groups. Swelling and redness were also common, but at the most one subject in each vaccine group reported swelling or redness of >50 mm in diameter.

Pain at the injection site was the most persistent local reaction in all vaccine groups. Most local reactions still ongoing on day 7 were reported to be mild or moderate in severity.

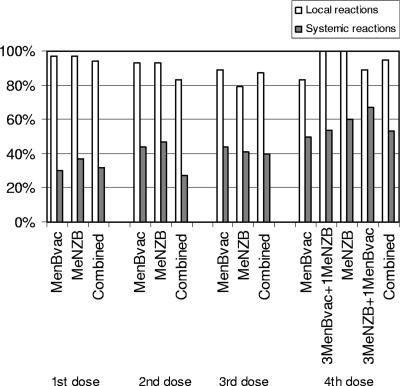

Most local reactions began within 48 h after vaccination. Overall, the frequency and the severity profiles of the local reactions were similar in the different vaccine groups and did not appear to correlate to the number of doses received by the subjects (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Local and systemic reactions after vaccination. Local reactions were redness, swelling, pain, and induration. Systemic reactions were nausea, malaise, arthralgia, and headache. For the numbers of subjects (N) in each group, see Fig. 1.

Systemic reactions.

The most commonly reported systemic reactions were malaise and headache, which were reported by from 29 to 50% of the subjects across the three vaccine groups within the primary vaccination series (Fig. 2). A severe intensity of systemic reactions was reported by only a few subjects, and the majority of all systemic reactions were short lasting.

There was a trend for the systemic reactions to be more frequently reported after the booster dose than after the first three doses.

The overall frequency and the severity profile of each systemic reaction were similar among the three vaccine groups within the primary immunization schedule, while variations were observed for the booster dose, likely due to the small number of subjects per group (Fig. 2).

Three subjects (one in the MenBvac group and two in the MeNZB group) experienced mild fever (38°C to <39°C) within the three-dose primary schedule, and one subject (in the group receiving four doses of MeNZB) experienced mild fever after the booster dose.

DISCUSSION

Use of a combination of the two safe and efficacious vaccines, MenBvac (2, 19) and MeNZB (21), is one way to increase protection against serogroup B meningococcal disease when different strains are circulating. These two vaccines will cover the most commonly occurring serogroup B strains in many European countries (17, 29). The results from the primary immunizations showed that the combined vaccine was immunogenic with regard to both vaccine strains and that the responses were of the same magnitude as the homologous responses observed for each individual vaccine, even though the dose was only half. No negative interaction either with regard to immunogenicity or with regard to safety was observed when the combined vaccine was given. For both strains, there was a trend toward higher titers/responses in all four groups receiving at least one dose containing the respective strain-specific (homologous) vaccine than in the group receiving all four doses of the vaccine against the heterologous strain.

Although the number of vaccinees analyzed in this study was small, the results shown here (Table 4 and 5) indicate that subjects who are primed earlier with three doses of an OMV vaccine based on a heterologous strain will probably obtain protection after a booster dose of a vaccine based on the epidemic strain. Similar observations were reported by Moe et al. after sequential immunization of mice and guinea pigs with OMVs and microvesicles from different heterologous meningococcal strains (15). Luijkx et al. have also studied a prime-boost strategy with heterologous OMV vaccines in mice (12). Their conclusion was that a specific priming rather than a specific boosting with monovalent OMVs resulted in a significant rise in the serosubtype-specific immune response against a weakly immunogenic PorA.

In this study two functional tests measuring antimeningococcal activity, SBA and OPA, were used. The SBA measures functional antibodies with bactericidal activity, and for serogroup B, SBA titers of ≥4 have been suggested to correlate with protection (4, 10). It has been suggested that OPA is also an important defense mechanism against meningococcal infections, especially those caused by serogroup B organisms (23, 28). Only antibodies that bind to the surface of live meningococci will induce OPA, and OPA thereby reflects the cellular killing of meningococci induced by specific antibodies. Both mechanisms are probably important for protection against meningococcal disease. In our study a higher proportion of subjects responded in the OPA assay than in the SBA, suggesting that the protection elicited by the vaccines tested may be higher than the results from the SBA indicate.

In countries where several different serogroup B strains are responsible for systemic meningococcal disease, cross-reactive antibodies are of importance. Although the OMV vaccines are mainly PorA specific in infants (26), significant cross-reactivity was observed in adolescents and adults (5, 8, 22, 26). In this trial significant cross-reactivity between the two tested strains was also observed. However, the cross-reactivity against more strains and clones needs further investigation.

This study was conducted with adults since it was the first time that this vaccine combination was tested. However, the proposed schedule for the combination could be used for individuals down to the age of infants. It is reasonable to assume that in younger age groups the safety and reactogenicity profiles as well as the positive interaction profile of this combination will be similar to those in older individuals.

The concept of combining outer membrane proteins from different strains in one vaccine has also been investigated by others. Similar to the bivalent vaccine that we have described here, Boutriau et al. (5) tested another bivalent serogroup B OMV vaccine, prepared with a combination of B:4:P1.19,15 and B:4:P1.7-2,4 meningococcal strains. In that study the bivalent vaccine was demonstrated to induce bactericidal antibodies against both the vaccine-homologous, PorA-related strains and heterologous strains. Other trials investigating combined OMV vaccines based on several PorA proteins from different strains have demonstrated large variations in the responses to the individual PorA proteins (6, 30).

The safety profiles of the combined vaccine and the vaccines given within the crossover regimen were similar to those reported in other studies showing that MenBvac (8, 19) and MeNZB (21) are safe and well tolerated when they are given separately within a classical vaccination schedule.

More specifically, the most common adverse reaction was local pain, which is consistent with earlier data (18). Most of the local and systemic reactions were of mild or moderate intensity. Subjects who experienced local reactions of severe intensity after the first vaccine dose did not frequently report severe local reactions after the subsequent doses. Adverse events other than local and systemic reactions were not commonly reported, and no serious adverse event possibly related to the administration of MenBvac or MeNZB was reported. Although all three vaccine regimens were reactogenic, the benefits of immunization with either vaccine by far override the risks in an epidemic setting or local outbreak. A combined vaccine might at present be the best option if different strains of serogroup B are included in the clinical picture.

In conclusion, the results obtained with the primary immunization schedule showed that the combined vaccine was immunogenic with regard to both vaccine strains and that the responses were of the same magnitude as the homologous responses observed for each individual vaccine, although the antigen amount was only half that of the monovalent vaccine. This may have a great impact in outbreaks of serogroup B meningococcal disease caused by different strains.

Acknowledgments

The study was sponsored by NIPH and Novartis Vaccines S.r.l.

We thank the students who participated in the study and the study team at NIPH, especially Aslaug Flydal, Inger Lise Haugen, Kirsten Konsmo, Tove Karin Herstad, and Venelina Kostova. We also thank Karin Gewert at Writewise for skillful assistance.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 18 July 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aase, A., L. M. Naess, R. H. Sandin, T. K. Herstad, F. Oftung, J. Holst, I. L. Haugen, E. A. Høiby, and T. E. Michaelsen. 2003. Comparison of functional immune responses in humans after intranasal and intramuscular immunisations with outer membrane vesicle vaccines against group B meningococcal disease. Vaccine 212042-2051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bjune, G., E. A. Høiby, J. K. Grønnesby, O. Arnesen, J. H. Fredriksen, A. Halstensen, E. Holten, A. K. Lindbak, H. Nøkleby, and E. Rosenqvist. 1991. Effect of outer membrane vesicle vaccine against group B meningococcal disease in Norway. Lancet 3381093-1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borrow, R., I. S. Aaberge, G. F. Santos, T. L. Eudey, P. Oster, A. Glennie, J. Findlow, E. A. Høiby, E. Rosenqvist, P. Balmer, and D. Martin. 2005. Interlaboratory standardization of the measurement of serum bactericidal activity by using human complement against meningococcal serogroup B, strain 44/76-SL, before and after vaccination with the Norwegian MenBvac outer membrane vesicle vaccine. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 12970-976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borrow, R., P. Balmer, and E. Miller. 2005. Meningococcal surrogates of protection-serum bactericidal antibody activity. Vaccine 232222-2227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boutriau, D., J. Poolman, R. Borrow, J. Findlow, J. Diez Domingo, J. Puig-Barbera, J. M. Baldo, V. Planelles, A. Jubert, J. Colomer, A. Gil, K. Levie, A. D. Kervyn, V. Weynants, F. Dominguez, R. Barbera, and F. Sotolongo. 2006. Immunogenicity and safety of three doses of a bivalent (B:4:P1.19,15 and B:4:P1.7-2,4) meningococcal outer membrane vesicle vaccine in healthy adolescents. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 465-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Kleijn, E., L. van Eijndhoven, C. Vermont, B. Kuipers, H. van Dijken, H. Rumke, R. de Groot, L. van Alphen, and G. van den Dobbelsteen. 2001. Serum bactericidal activity and isotype distribution of antibodies in toddlers and schoolchildren after vaccination with RIVM hexavalent PorA vesicle vaccine. Vaccine 20352-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dyet, K., A. Devoy, R. McDowell, and D. Martin. 2005. New Zealand's epidemic of meningococcal disease described using molecular analysis: implications for vaccine delivery. Vaccine 232228-2230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feiring, B., J. Fuglesang, P. Oster, L. M. Næss, O. S. Helland, S. Tilman, E. Rosenqvist, M. A. Bergsaker, H. Nøkleby, and I. S. Aaberge. 2006. Persisting immune responses indicating long-term protection after booster dose with meningococcal group B outer membrane vesicle vaccine. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 13790-796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frasch, C. E., L. van Alpen, J. Holst, J. T. Poolman, and E. Rosenqvist. 2001. Outer membrane protein vesicle vaccines for meningococcal disease. In A. J. Pollard and M. C. J. Maiden (ed.), Methods in molecular medicine, vol. 66. Meningococcal vaccines. Humana Press, Totowa, NJ. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Holst, J., B. Feiring, J. E. Fuglesang, E. A. Høiby, H. Nøkleby, I. S. Aaberge, and E. Rosenqvist. 2003. Serum bactericidal activity correlates with the vaccine efficacy of outer membrane vesicle vaccines against Neisseria meningitidis serogroup B disease. Vaccine 21734-737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holst, J., I. S. Aaberge, P. Oster, D. Lennon, D. Martin, J. O'Hallahan, K. Nord, H. Nøkleby, L. M. Næss, K. Møyner, P. Kristiansen, A. G. Skryten, K. Bryn, A. Aase, R. Rappuoli, and E. Rosenqvist. 24 July 2003. A ‘tailor made’ vaccine trialled as part of public health response to group B meningococcal epidemic in New Zealand. Eurosurv. Wkly. http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ew/2003/030724.asp#5.

- 12.Luijkx, T., H. van Dijken, C. van Els, and G. van den Dobbelsteen. 2006. Heterologous prime-boost strategy to overcome weak immunogenicity of two serosubtypes in hexavalent Neisseria meningitidis outer membrane vesicle vaccine. Vaccine 241569-1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Michaelsen, T. E., and A. Aase. 2001. Antibody-induced opsonophagocytosis of serogroup B meningococci measured by flow cytometry, p. 331-337. In A. J. Pollard and M. C. J. Maiden (ed.), Methods in molecular medicine, vol. 66. Meningococcal vaccines. Humana Press, Totowa, NJ. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ministry of Health. 8 Aug 2006. Meningococcal B Immunisation Programme effectiveness shown. http://www.moh.govt.nz/moh.nsf/pages/MH5042.

- 15.Moe, G. R., P. Zuno-Mitchell, S. N. Hammond, and D. M. Granoff. 2002. Sequential immunization with vesicles prepared from heterologous Neisseria meningitidis strains elicits broadly protective serum antibodies to group B strains. Infect. Immun. 706021-6031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Næss, L. M., T. Torill, A.-C. Kristoffersen, I. S. Aaberge, E. A. Høiby, and E. Rosenqvist. 2002. Immunogenicity of a combination of two different outer membrane protein based meningococcal group B vaccines, p. 284. In D. A. Caugant and E. Wedege (ed.), Abstr. 13th Int. Pathogenic Neisseria Conf., Oslo 2002. Nordberg Aksidenstrykkeri AS, Oslo, Norway.

- 17.Noah, N., and B. Henderson. 2002. Surveillance of bacterial meningitis in Europe 1999/2000. Abridged version. Communicable Disease Surveillance Center, Public Health Laboratory Service, London, United Kingdom. http://www.hpa.org.uk/hpa/inter/m_surveillance9900.pdf. Accessed 23 August 2006.

- 18.Nøkleby, H., and B. Feiring. 1991. The Norwegian meningococcal group B outer membrane vesicle vaccine: side effects in phase II trials. NIPH Ann. 1495-102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nøkleby, H., P. Aavitsland, J. O'Hallahan, B. Feiring, S. Tilman, and P. Oster. 2007. Safety review: two outer membrane vesicle (OMV) vaccines against systemic Neisseria meningitidis serogroup B disease. Vaccine 253080-3084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oster, P., D. Lennon, J. O'Hallahan, K. Mulholland, S. Reid, and D. Martin. 2005. MeNZB: a safe and highly immunogenic tailor-made vaccine against the New Zealand Neisseria meningitidis serogroup B disease epidemic strain. Vaccine 232191-2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oster, P., J. O'Hallahan, I. Aaberge, S. Tilman, E. Ypma, and D. Martin. 2007. Immunogenicity and safety of a strain-specific MenB OMV vaccine delivered to under 5-year olds in New Zealand. Vaccine 253075-3079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosenqvist, E., E. A. Høiby, E. Wedege, K. Bryn, J. Kolberg, A. Klem, E. Rønnild, G. Bjune, and H. Nøkleby. 1995. Human antibody responses to meningococcal outer membrane antigens after three doses of the Norwegian group B meningococcal vaccine. Infect. Immun. 634642-4652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ross, S. C., P. Rosenthal, H. M. Berberich, and P. Densen. 1987. Killing of Neisseria meningitidis by human neutrophils: implications for normal and complement-deficient individuals. J. Infect. Dis. 1551266-1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sexton, K., D. Lennon, P. Oster, S. Crengle, D. Martin, K. Mulholland, et al. 2004. The New Zealand meningococcal vaccine strategy: a tailor-made vaccine to combat a devastating epidemic. N. Z. Med. J. 117U1015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sierra, G. V., H. C. Campa, N. M. Varcacel, I. L. Garcia, P. L. Izquierdo, P. F. Sotolongo, G. V. Casanueva, C. O. Rico, C. R. Rodriguez, and M. H. Terry. 1991. Vaccine against group B Neisseria meningitidis: protection trial and mass vaccination results in Cuba. NIPH Ann. 14195-207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tappero, J. W., R. Lagos, A. M. Ballesteros, B. Plikaytis, D. Williams, J. Dykes, L. L. Gheesling, G. M. Carlone, E. A. Høiby, J. Holst, H. Nøkleby, E. Rosenqvist, G. Sierra, C. Campa, F. Sotolongo, J. Vega, J. Garcia, P. Herrera, J. T. Poolman, and B. A. Perkins. 1999. Immunogenicity of 2 serogroup B outer-membrane protein meningococcal vaccines. A randomized controlled trial in Chile. JAMA 2811520-1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thornton, V., D. Lennon, K. Rasanathan, J. O'Hallahan, P. Oster, J. Stewart, S. Tilman, I. Aaberge, B. Feiring, and H. Nøkleby. 2006. Safety and immunogenicity of New Zealand strain meningococcal serogroup B OMV vaccine in healthy adults: beginning of epidemic control. Vaccine 241395-1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Toropainen, M., L. Saarinen, G. Vidarsson, and H. Kayhty. 2006. Protection by meningococcal outer membrane protein PorA-specific antibodies and a serogroup B capsular polysaccharide-specific antibody in complement-sufficient and C6-deficient infant rats. Infect. Immun. 742803-2808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tzanakaki, G., and P. Mastrantonio. 2007. Aetiology of bacterial meningitis and resistance to antibiotics of causative pathogens in Europe and in the Mediterranean region. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 29621-629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van den Dobbelsteen, G. P., H. H. van Dijken, S. Pillai, and L. van Alphen. 2007. Immunogenicity of a combination vaccine containing pneumococcal conjugates and meningococcal PorA OMVs. Vaccine 252491-2496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wyle, F. A., M. S. Artenstein, B. L. Brandt, E. C. Tramont, D. L. Kasper, P. L. Altieri, S. L. Berman, and J. P. Lowenthal. 1972. Immunologic response of man to group B meningococcal polysaccharide vaccines. J. Infect. Dis. 126514-522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]