Abstract

The proper function of many tissues depends critically on the structural organization of the cells and matrix of which they are comprised. Therefore, in order to engineer functional tissue equivalents that closely mimic the unique properties of native tissues it is necessary to develop strategies for reproducing the complex, highly organized structure of these tissues. To this end, we sought to develop a simple method for generating cell sheets that have defined ECM/cell organization using microtextured, thermoresponsive polystyrene substrates to guide cell organization and tissue growth. The patterns consisted of large arrays of alternating grooves and ridges (50 μm wide, 5 μm deep). Vascular smooth muscle cells cultured on these substrates produced intact sheets consisting of cells that exhibited strong alignment in the direction of the micropattern. These sheets could be readily transferred from patterned substrates to non-patterned substrates without the loss of tissue organization. Ultimately, such sheets will be layered to form larger tissues with defined ECM/cell organization that spans multiple length scales.

Introduction

The structural organization of cells and extracellular matrix (ECM) in native tissues is crucial for proper function, particularly in load-bearing and muscular tissues [1]. Therefore, as the field of tissue engineering matures and begins to move towards creating larger, more complicated tissues and organs, the need arises to develop strategies for growing tissues with precise structural features that can be controlled over multiple length scales. Currently, many popular approaches to tissue construction employ isotropic scaffolds or substrates that do not possess any specific organizational cues to guide tissue development, resulting in tissues that rarely possess the structural properties of the native tissues that they are designed to replace. For example, this is the case for arterial tissue, where the development of a functional tissue engineered artery that possesses the unique, anisotropic mechanical properties of the native vessel remains elusive [2-4]. This is due, in part, to the difficulty in adequately mimicking the structural organization of the artery wall, which derives its properties from its complex organization of matrix proteins and cells [5-7]. The medial layer of the artery wall is believed to be the principal load-bearing layer and is composed of alternating layers of smooth muscle cells (SMCs) embedded in collagen and elastin lamellae. The collagen and SMCs are arranged in a helical pattern around the circumference of the vessel, with the direction of the pitch alternating between successive layers [8]. This helical arrangement not only provides enhanced circumferential load-bearing properties to tissue, but also imparts torsional stability. Furthermore, this arrangement of the SMCs allows for more efficient control of vessel tone (which in turn dictates blood pressure and shear stress) as this configuration leads to SMC contraction that primarily results in a reduction of the vessel lumen diameter rather than its length. Attempts to specifically engineer such organization into tissue engineered arteries have met with differing degrees of success. While biopolymer-based tissues have been shown to possess the proper alignment of matrix components [9-11] and exhibit mechanical anisotropy [12], their overall mechanical properties are not sufficient for implantation [13]. On the other hand, tissue engineered grafts made solely from cell-secreted ECM, using a “self-assembly” or cell sheet-based approach, could support high burst pressures and have shown success in vivo, yet lacked the desired organization [14]. However, further refinement of this approach using static mechanical load to align matured cell sheets has resulted in tissues with the desired cell/matrix organization and mechanical anisotropy [15]. These results are extremely encouraging, however, this method requires increasing the already lengthy incubation time in order generate such organization.

Cell sheet engineering has arisen recently as an attractive approach to tissue engineering. In this approach, confluent cell cultures are harvested from a variety of substrates as intact, tissue-like sheets consisting of the cells and their associated extracellular matrix (ECM) [16, 17]. These sheets can then be used individually or layered/rolled to create tissues of larger size or with defined laminar organization. In particular, cell sheet engineering using thermoresponsive cell culture substrates has enabled this approach to be extended to a wide variety of tissue types and therapies [17]. Tissue culture dishes treated with a thin layer of the thermoresponsive polymer poly (N-isopropylacrylamide) (PIPAAm) can support cell adhesion and growth at 37°C (where the PIPAAm is hydrophobic) [18], while lowering the temperature below its lower critical solution temperature (32°C) causes the polymer to become hydrophilic and swell [19]. This swelling induces the cells and any associated ECM to lift off the surface of the culture dish while maintaining cell-cell and cell-ECM connections [20-24], which are crucial for proper tissue function. This is in contrast to typical methods of cell adhesion disruption that usually include treatment with digestive enzymes, such as trypsin, that destroy these important connections. While this technology has proven to be a highly effective means of engineering tissues, the resulting cell sheets lack any sort of structural organization due to a lack of organizational cues from the substrates. Methods have been developed to prepare substrates to control the spatial distribution of cells [25, 26], but these approaches require multiple complicated steps and were designed with spatially segregating multiple cell types as opposed to defining the structural organization of the cells and matrix themselves.

Micropatterning has been widely used as a method of controlling cell morphology, spatial arrangement, and function [27, 28] by imparting various types of cell-scale guidance cues by controlling regions of adhesion [25, 29-31], topology [32-37], and “direct writing” of scaffolds and cells [38-40]. A common method used in many of these approaches involves a set of techniques known as soft lithography [41]. Soft lithography uses a stamp or mold prepared by casting an elastomer, typically polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), against a master containing a patterned relief structure prepared via traditional photolithography techniques. These materials can then serve as stamps that can be used to deposit molecules in precise patterns via microcontact printing in order to spatially control cell adhesion [29, 31], as well as being used as topological cues themselves, mimicking the 3-dimensional nano- and microstructure of the native ECM [34]. A particularly attractive use for these molds is for hot embossing of thermoplastic polymers (e.g., polystyrene (PS)) in order to create substrates with topological features on the micron- and submicron-scale [32, 37, 42]. By pressing a micropatterned PDMS mold against a thin sheet of PS and heating it above the glass transition temperature of PS, it is possible to accurately and reproducibly transfer a micropattern from a PDMS mold to a PS substrate [32]. This technique provides a simple, single-step method of micropatterning substrates while maintaining chemical uniformity at the surface, which is not possible with microcontact printing, making them ideal for grafting with PIPAAm using published protocols [18].

By combining the techniques of hot embossing and PIPAAm grafting, we have been able to generate thermoresponsive, microtextured substrates that support cell adhesion and growth. Here, we describe a simple technique for creating such substrates and examine the morphological properties of the resulting cell sheets. SMCs grown on these substrates conformed to the topology of the substrates by orienting in the direction of microtextured grooves and quickly grew to confluence over the entire surface of the substrates. The resulting cell sheets could be easily detached from the substrates by simply lowering the culture temperature and transferred to non-patterned substrates without loss of cell or ECM organization.

Materials and Methods

Microtexturing

Microtextured polystyrene substrates were prepared by hot embossing thin polystyrene films with microtextured polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) molds containing an array of parallel grooves (50 μm wide, spaced 50 μm apart, 5 μm deep). The PDMS molds were generated using conventional photolithography and soft lithography techniques as previously described [34]. Briefly, patterned silicon wafers were made by applying a layer of SU-8 3005 photoresist (MicroChem Corp., Newton, MA, USA) onto 4-inch silicon wafers using a spincoater (Active Co., Ltd., Saitama City, Japan). The wafers exposed to UV light through a patterned photomask using a BA100 mask aligner (Nanometric Technology, Inc., Tokyo, Japan) and developed using ethyl lactate. The patterned wafers were then silanized using a solution of 2% dimethyloctadecylchlorosilane (Shin Etsu Chemical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) in toluene before curing PDMS (Silpot 184, Dow Corning, Tokyo, Japan) against the patterned wafers. Removal of the PDMS from the wafers (facilitated by the silanization treatment) yielded microtextured PDMS master molds. It should be noted that the printing process yielded photomasks with lines slightly wider than the expected 50 μm, resulting in ridges on the wafers that were slightly wider (51.4±1.4 μm) than the grooves (49.0±0.7 μm).

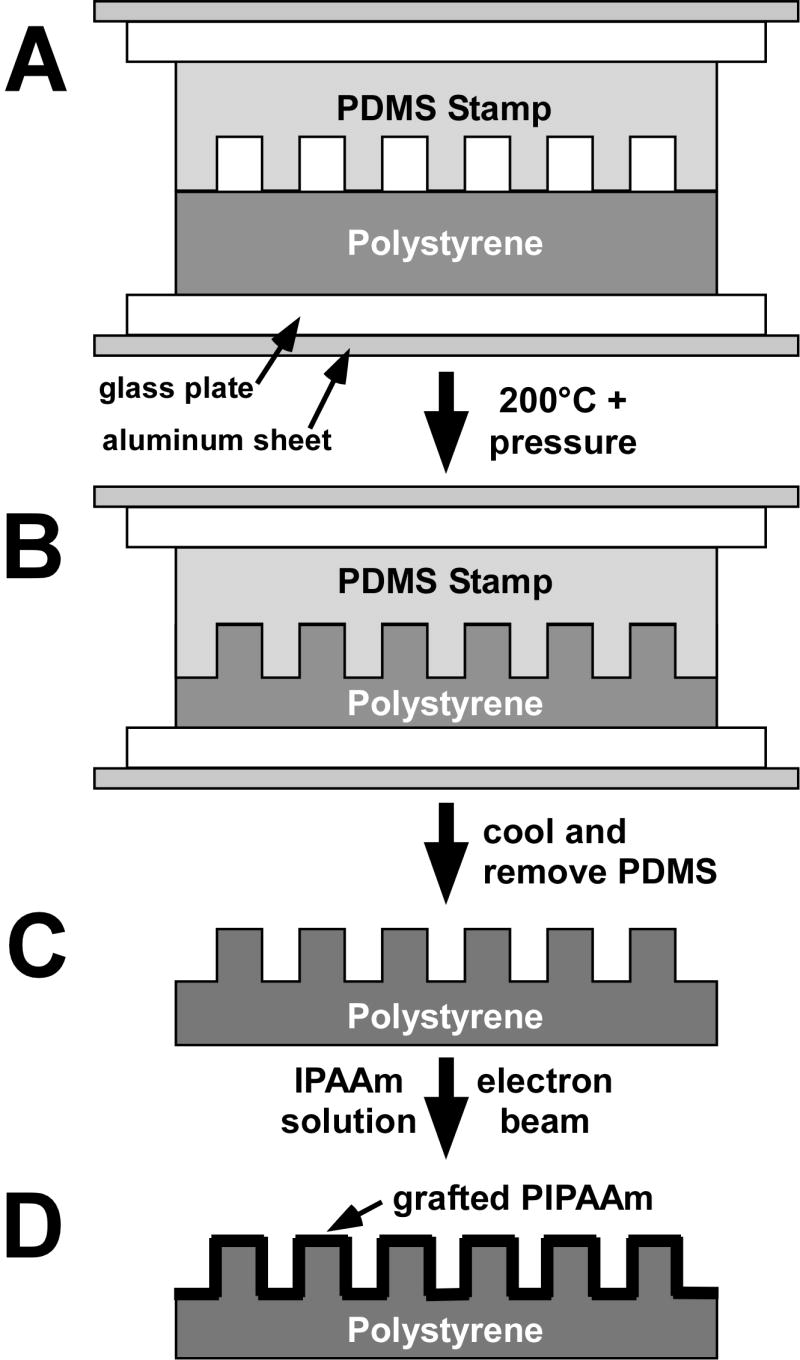

Hot embossing of the polystyrene (PS) was accomplished by pressing the microtextured PDMS master molds against a 250 μm-thick PS sheet (a kind gift from Mitsubishi Chemical Co., Tokyo, Japan) using a custom-built device (Figure 1) in an oven for 5 minutes at 200°C. Non-microtextured control substrates were generated by using a non-microtextured PDMS mold instead of a microtextured PDMS mold. Upon removal from the oven, the device was allowed to cool for at least 5 minutes before removing the PS sheet from the device. The sheets were washed several times in ethanol and examined using a scanning electron microscope to verify that the pattern was properly transferred from the PDMS to the PS. The PDMS molds could be reused more than 50 times without loss or damage to the micropattern.

Figure 1. Polystyrene substrate microtexturing and PIPAAm grafting.

Hot embossing of the PS sheets was accomplished by pressing the microtextured PDMS master molds against a polystyrene sheet between aluminum and glass plates using a custom-built device (A). This device was placed in an oven for 5 minutes at 200°C (B) and subsequently cooled for 5 minutes before removing the PS sheet from the device (C). PS substrates were grafted with PIPAAm by first applying a thin layer of IPAAm dissolved in isopropanol to the surface of the substrate and then exposing them to electron beam irradiation (D). Grafted substrates were washed overnight in deionized water and subsequently dried at 45°C. Pattern dimensions are exaggerated for illustrative purposes.

Polymer Grafting

Microtextured and non-microtextured PS substrates were grafted with PIPAAm as described previously for TCPS dishes [43]. Briefly, IPAAm monomer (a kind gift from Kohjin Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) was first purified by recrystallization from n-hexane. A thin layer of IPAAm solution (dissolved in 2-propanol) was spread over the upper surface of PS substrates (i.e., textured-surface), which were subsequently exposed to electron beam irradiation using an Area Beam Electron-Processing System (Nissin-High Voltage Co. Ltd., Kyoto, Japan), resulting in polymerization and covalent grafting onto the PS sheets. Grafted substrates were washed overnight in deionized water and subsequently dried at 45°C. Substrates grafted with solutions containing 40%, 45%, 50%, and 55% IPAAm were investigated in this study.

Scanning electron microscopy of substrate surfaces

PDMS, non-grafted microtextured PS and PIPAAm-grafted microtextured PS substrates were examined with a scanning electron microscope (VE-9800(KEYENCE Co., Osaka, Japan). Samples did not require surface treatment to enhance visualization.

Cell Seeding

Grafted and un-grafted microtextured PS substrates as well as grafted and ungrafted non-microtextured PS substrates were sterilized by soaking in 70% ethanol for one hour, transferring them to sterile culture dishes where they were allowed to dry completely, and finally exposing them to UV light in a clean bench for 30 minutes. To promote cell attachment, substrates were incubated overnight in fetal bovine serum at 37°C. Adult human aortic smooth muscle cells (AoSMCs) (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) were seeded onto substrates at a concentration of 40,000 cells/cm2. Seeded substrates were cultured in SmGM-2 medium (Lonza) for up to two weeks post-seeding. AoSMCs between passages 7 and 10 were used in this study.

Cell Orientation and Elongation

To investigate the orientation of the cells on both microtextured and non-microtextured substrates, cell nuclei were stained by incubating the cultures in standard culture medium containing Hoechst 33342 (Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, CA, USA) at a dilution of 1:1000 for 30 minutes. The cultures were then washed three times with PBS and immediately imaged under epifluorescence using an Eclipse TE2000-U microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) and processed with Axio Vision v4.2 (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). For each substrate, five images were taken at random locations. Cell orientation was assessed by measuring the angle between the long axis of the nucleus [44] and the direction of the grooves using ImageJ v1.38 (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA). For non-microtextured substrates, this angle was arbitrarily chosen for each image.

Cytoskeletal organization was assessed by staining f-actin fibrils in the cell sheets with phalloidin. Briefly, samples were fixed with pre-warmed 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min and then rinsed three times with phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Next, cells were permeabilized with 0.5% TritonX-100 (Sigma) for 10 min at room temperature and rinsed three times with PBS. Samples were blocked with 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) solution for 1 hr at 37°C and then incubated with Alexa Fluor 568 Phalloidin (Molecular Probes; 1:200 dilution) for 2 hr at 37°C. Samples were rinsed three times with BSA, covered with fresh PBS, and then imaged.

Cell Sheet Detachment and Transfer

For confirmation of the thermoresponsive nature of the substrates, the temperature of the cultures was dropped to 20°C and imaged at 5-minute and 45-minute time points to assess cell detachment. Transfer of cell sheets from one surface to another was performed using the protocol described by Tsuda et al. [26]. Briefly, a custom-built sheet manipulator was coated with a thin layer of gelatin (1.5 mm thick) and then placed over the top of a cell sheet and incubated for 20 min at 20°C, allowing the cell sheet to detach from the culture dish and adhere to the gelatin. The manipulator was then removed from the culture dish (with the cell sheet attached), transferred to another dish, and incubated for 20 min at 20°C. Cell culture medium at 37°C was then added for 15 minutes in order for the cell sheet to adhere to the new substrate and the gelatin to melt. The medium (containing the gelatin) was aspirated and fresh medium was carefully added to the new culture dishes.

Results

Substrate topology

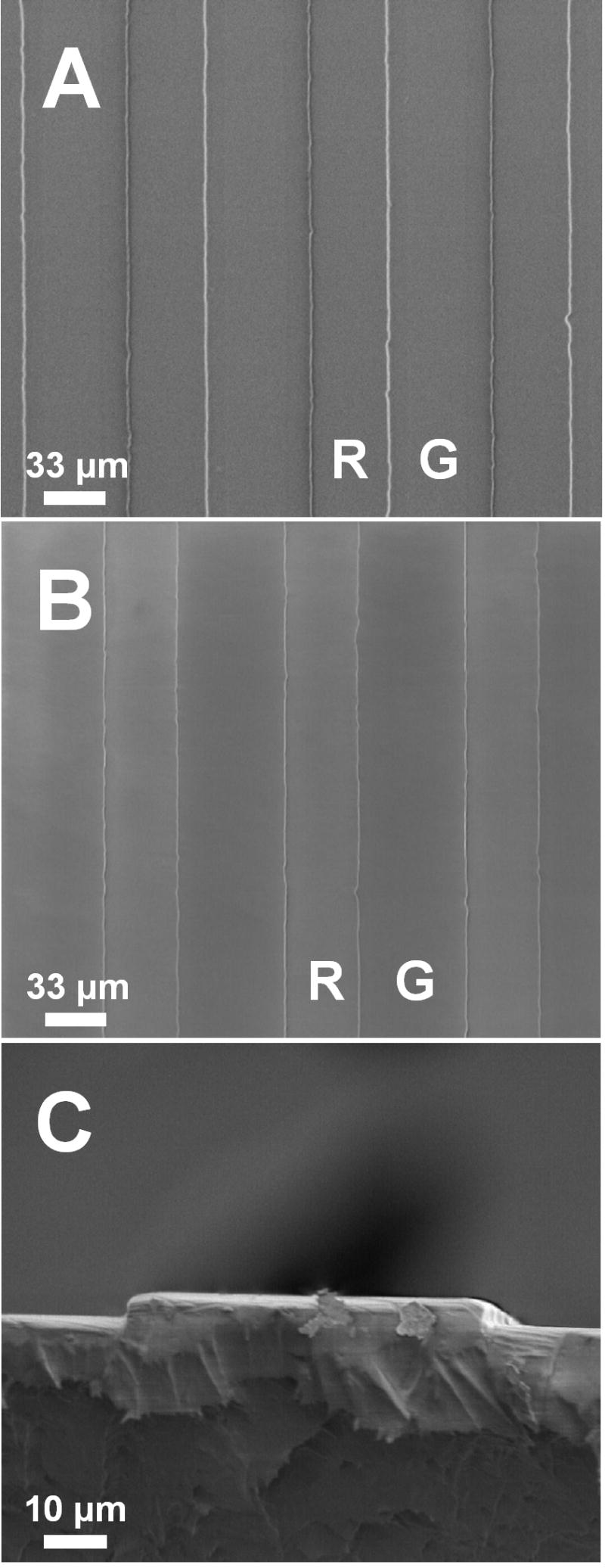

The double transfer of the micropattern (silicon wafer to PDMS to PS) should result in the micropattern on the PS sheets being the same as the one on the silicon wafers. SEM images of the substrates confirmed that the micropattern was accurately transferred from the wafer to the PDMS molds and from the PDMS to the PS sheets (Figure 2). The ridges were slightly wider than the grooves for the reasons noted in the Methods section. The depth of the grooves was approximately 5 μm.

Figure 2. SEM of microtextured substrates.

Scanning electron microscope images of PS substrates show accurate transfer of the microtexture from the PDMS mold (A) to the PS substrate (B). The ridge and groove regions of the substrates are marked with R and G, respectively. Panel C shows a cross-section of a microtextured PS substrate showing the microtexture height is approximately 5 μm.

Cell sheet detachment

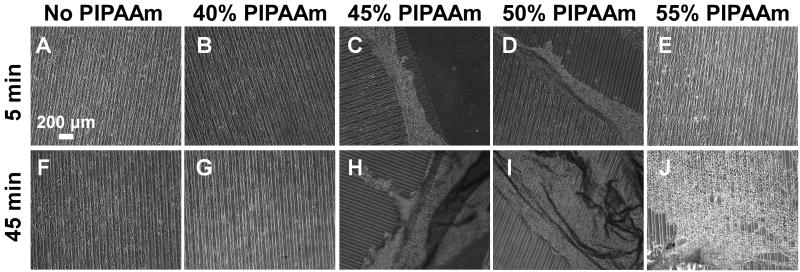

Cell sheets could be easily detached from the PIPAAm-grafted microtextured PS substrates by reducing the temperature of the cultures to 20°C (Figure 3). As expected, cell sheets grown on substrates that had not been grafted with PIPAAm did not detach. Substrates grafted with 40% IPAAm did not support cell sheet detachment within 45 minutes. In fact, these sheets, as well as the sheets on substrates without PIPAAm, did not detach after 24 hours at 20°C (data not shown). Cell sheets grown on substrates made with 45% and 50% IPAAm began to detach within 5 minutes and could be completely removed by 45 minutes. Sheets grown on substrates made with 55% IPAAm began to detach within 45 minutes, but the sheets did not detach as intact sheets. Cells grown on sheets at this concentration occasionally exhibited clumping behavior and did not always achieve confluence (data not shown), indicating that unlike substrates grafted with 40-50% PIPAAm, substrates grafted with 55% PIPAAm did not fully support cell growth and sheet formation.

Figure 3. Thermoresponsive cell sheet detachment is dependent on PIPAAm grafting density.

The temperature of the cultures was dropped to 20°C and observed at 5 minute (A-E) and 45 minute (F-J) time points to assess cell detachment. Cell sheets grown on substrates without grafted PIPAAm (A, F) as well as those on 40% PIPAAm substrates (B, G) did not detach from the substrate within 45 minutes. Cell sheets grown on substrates made with 45% and 50% IPAAm began to detach within 5 minutes (C and D, respectively) and could be completely removed by 45 minutes (H and I, respectively). Sheets grown on substrates made with 55% IPAAm began to detach within 45 minutes, but did not detach as intact sheets (E, J).

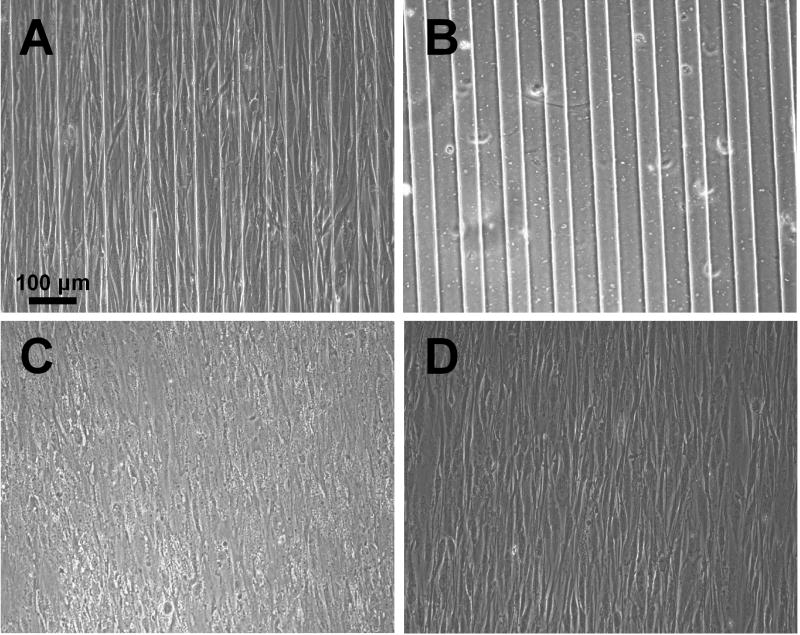

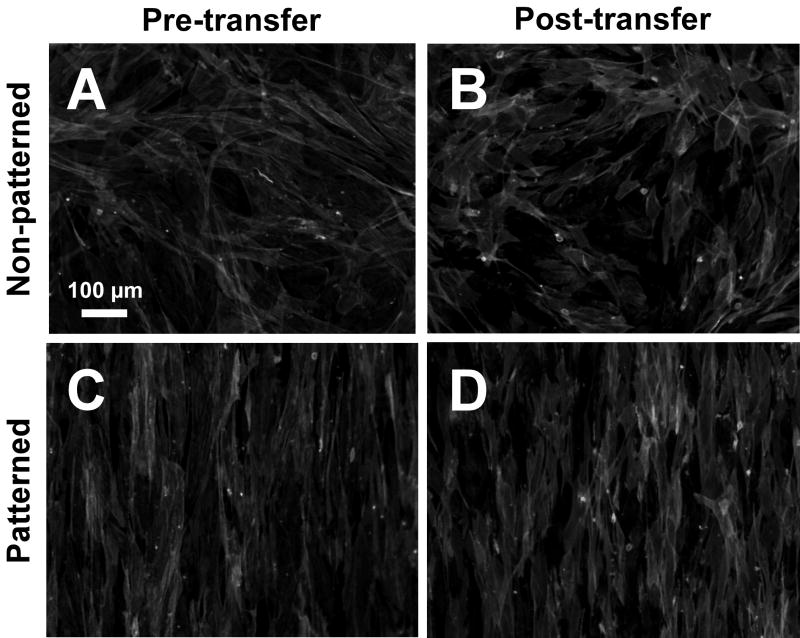

Cell orientation in cell sheets pre- and post-transfer

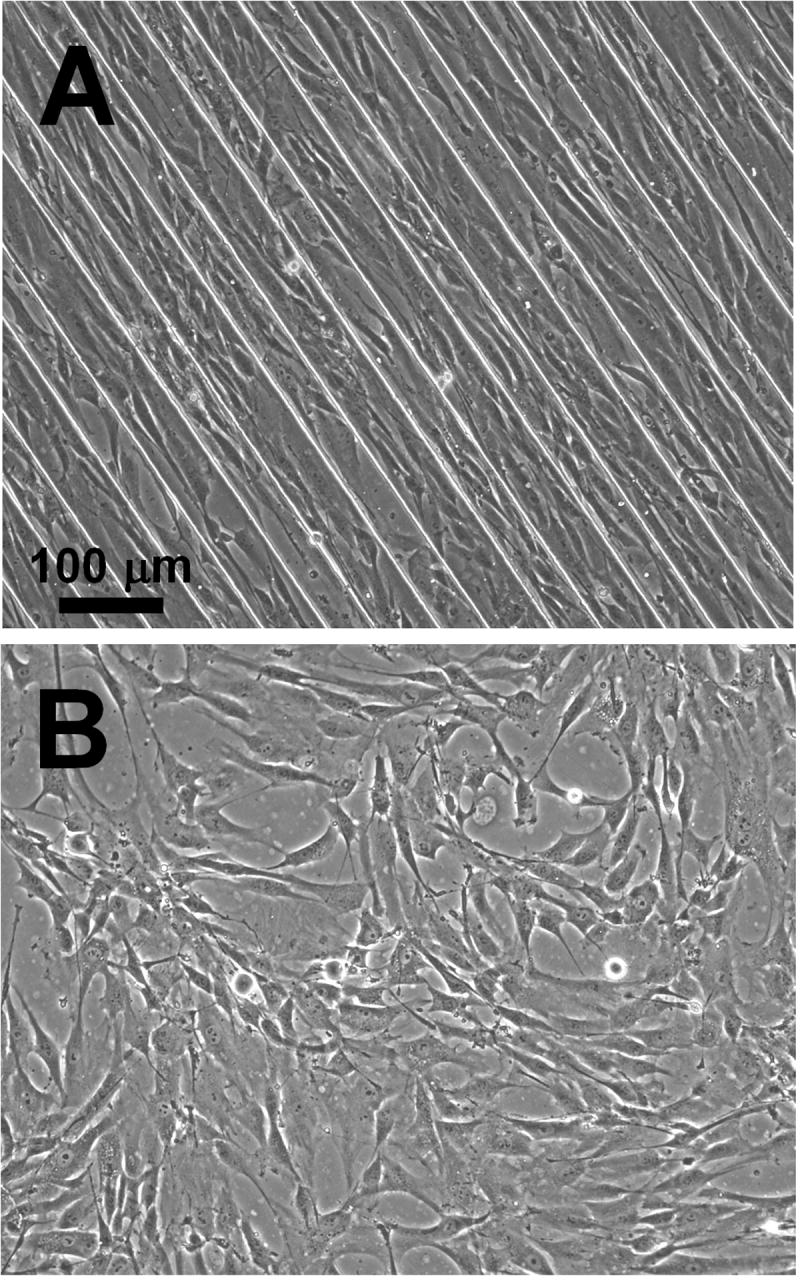

Figure 4 shows that cells grown on microtextured regions of the substrate oriented and elongated in the direction of the microtextured grooves, while cells on non-patterned regions did not appear to adopt any preferential orientation. This orientation was maintained following transfer of the cell sheets from PIPAAm-grafted microtextured PS substrates to normal, non-textured TCPS dishes using the gelatin manipulator technique (Figure 5). This result was further confirmed by assessing the cytoskeletal organization (f-actin fibrils) of the cells in the cell sheets before and after sheet transfer (Figure 6), which showed random organization on non-patterned substrates and highly oriented organization on microtextured substrates both before and after cell sheet transfer to TCPS substrates.

Figure 4. Cell sheets grown on microtextured, PIPAAm-grafted substrates orient in direction of micropattern.

Brightfield images of AoSMCs grown on microtextured PS substrates show that the cells oriented in the direction of the grooves (A), but oriented randomly on non-microtextured substrates (B). The substrates in these images were grafted with 45% PIPAAm.

Figure 5. Transferred cell sheets retain alignment.

Cell sheets grown on thermoresponsive, microtextured substrates were transferred to non-textured TCPS culture dishes using a custom-built gelatin-coated manipulator (see text for details) without loss of cell orientation: an organized cell sheet on a microtextured 45% PIPAAm-grafted substrate (A), the microtextured PIPAAm substrate after cell sheet had been removed showing no cells or matrix were left behind after detachment (B), the cell sheet attached to the gelatin-coated manipulator showing that the sheet remains organized following detachment (C), and the cell sheet attached to a non-patterned substrate post-transfer showing retention of cell/matrix organization.

Figure 6. Cell sheet cytoskeletal organization pre- and post-transfer.

Cytoskeletal organization of cell sheets was assessed by staining f-actin fibrils with Alexa Fluor 568 Phalloidin (Molecular Probes; 1:200 dilution). (A) Unpatterned, pre-transfer. (B) Unpatterned, post-transfer. (C) Patterned, pre-transfer. (D) Patterned, post-transfer. In panels A and C (pre-transfer), cell sheets were still attached to PIPAAm-grafted PS substrates, while in panels B and D (post-transfer), the cell sheets have been transferred from PIPAAm-grafted substrates to TCPS.

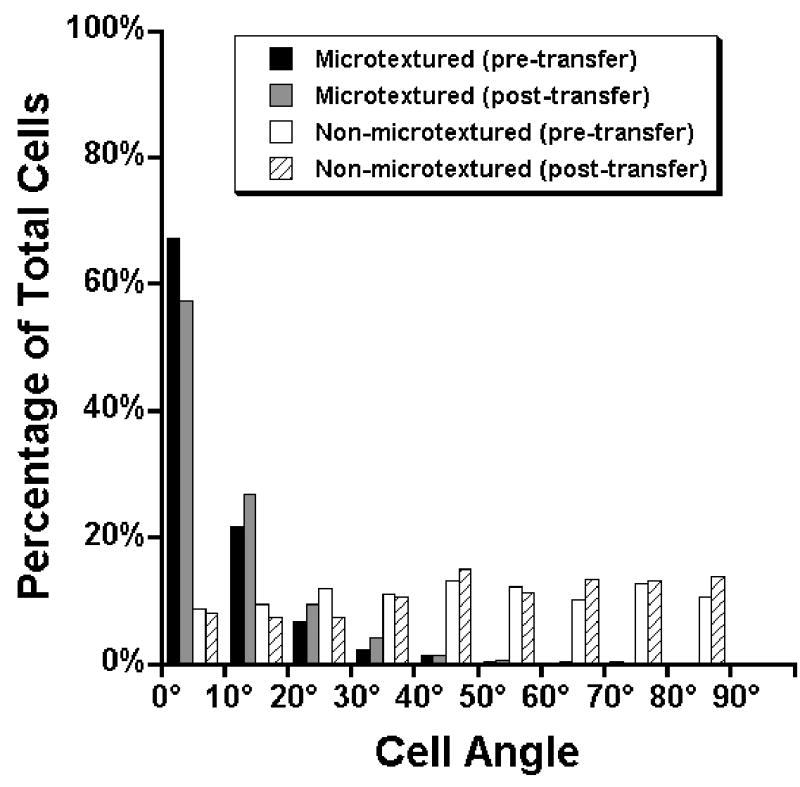

The orientation results were quantified by measuring the angle between the long axis of the nucleus and the direction of the grooves of cells grown on microtextured and non-microtextured substrates, both pre- and post-transfer (Figure 7). Most cells on microtextured substrates (95.7%) had orientation angles <30° (total cells measured, n=837), while cells on non-microtextured substrates had only 30.2% oriented in this direction with similar amounts oriented between 30°-60° (36.5%) and 60°-90° (33.3%) (n=696), indicating that these cells were randomly oriented. Following cell sheet transfer, there was no appreciable difference between the cell orientation angle distribution of the cell sheets before (n=837) and after (n=1032) transfer with a majority of cells having orientation angles <30° (95.7% and 93.5%, respectively), indicating that the microtextured substrate is not required to maintain cell orientation. As expected, the orientation angle distribution of cells grown on non-microtextured substrates was isotropic before (n=696) and after (n=957) sheet transfer.

Figure 7. Cell orientation distribution on microtextured and non-microtextured substrates, pre- and post-transfer.

Cell orientation was quantified staining the cell nuclei of cells grown on substrates grafted with 45% PIPAAm with Hoechst 33342 for 30 minutes. For each individual substrate, five images were taken at random locations under epifluorescence and the cell orientation was measured by finding the angle between the long axis of the nuclei and the direction of the grooves. An angle of 0° indicated parallel orientation to the grooves, while an angle of 90° indicates a perpendicular orientation to the grooves. For non-microtextured substrates, the angle was arbitrarily chosen for each image. Cells grown on non-microtextured substrates (white bars) showed random distribution of cell orientation angles (no preferential orientation), while cells grown on microtextured substrates (black bars) showed a strong orientation response in the direction of the grooves. For both microtextured and non-microtextured substrates, the distribution of cell orientation angles did not change appreciably following transfer via the gelatin manipulator method (gray bars and hatched bars, respectively).

Discussion

Given that the structural organization of tissues is a key factor in governing and maintaining tissue function, particularly in load-bearing and muscular tissues [1], we would like to understand how biomaterials can be used to guide the process of recapitulating native tissue organization. Individual cells are capable of modifying their local microenvironment, but are rarely capable of organizing themselves over length-scales required for tissue-level function. Achieving this high level of organization requires a template with the appropriate spatial, biological, and biophysical cues that enable the cells to organize over such length-scales. To this end, we have sought to develop a simple technique for engineering tissues with defined organization by combining the well-studied concepts of cell sheet engineering and micropatterning.

Cell sheet engineering using thermoresponsive substrates is an attractive tool for the development of engineered tissues that utilizes simple building blocks (single cell sheets) to construct of thick, dense tissues and forgoes the need for implantable scaffolds [17]. However, most sheets produced with this technology possess cells with random orientation and disorganized extracellular matrix. Constructing tissues with structural control at the nano- and microscale requires biomaterial substrates that contain chemical and topological features on these length scales. Other attempts at creating cell sheets with complex patterns required complicated, multistep application of surface coatings and cells [25, 26, 45] and have been limited to flat substrates. Microtexturing offers the advantage of providing a patterned substrate for cell growth with a contiguous layer of grafted PIPAAm, as opposed to patterned substrates that rely on regions of differing adhesion, allowing the cells to easily and quickly achieve full confluence in a single step. The combination of soft lithography and hot embossing employed in this study provided a simple method for producing materials patterned with feature sizes on the order of tens of microns. The data presented here are based on substrates consisting of parallel grooves 5 μm in depth and 50 μm wide, spaced 50 μm apart. The selection of this set of parameters was somewhat arbitrary as we have been able to achieve similar results with different combinations of groove width and spacing (20 to 80 μm; data not shown). Significantly deeper grooves have not been investigated; however, since tissues on the order of tens of microns thick are expected from cell sheet techniques, substrates with significantly deeper grooves may have an adverse effect on the resulting cell sheets. The thickness of the tissue growing on the ridges of such a substrate would be significantly thinner than the tissue in the grooves leading to an apparent weakening of the tissue in the direction perpendicular to the grooves. As the tissue will only be as strong as the thinnest region, this could potentially make such sheet more prone to tearing along the thinner ridge regions during handling. Furthermore, deeper grooves would likely lead to an increase in the time required for an intact sheet to form as the cells tend to first settle in the grooves and then grown onto the ridges. For the shallow grooves used here, this process occurs rather quickly (24-48 hours), presumably because the 5 μm depth does not provide a significant barrier for the cells to overcome, something which could potentially be an issue for cells grown on deeper grooves. As long as the chosen dimensions of the pattern induce the cells to orient with respect to the pattern, organized cells sheets can be grown; however, it is not clear whether the specific choice of pattern dimensions influences the long-term development of the cell sheet.

The dependence of cell sheet detachment on PIPAAm grafting density is interesting, if not particularly surprising. It is assumed that the cell sheet adhesion is disrupted when grafted PIPAAm layer swells when the culture temperature is dropped below its lower critical solution temperature [46, 47]. For the trivial case of a non-grafted surface, no swelling occurs at the surface and, therefore, no cell detachment occurs. At lower grafting densities (40% PIPAAm), the cells readily spread and grew on the surface but did not detach when the culture temperature was lowered to 20°C. This is likely due to the fact that at lower grafting densities, most of the PIPAAm was tightly associated with the PS substrate and had limited chain mobility, which prevented the PIPAAm from swelling to the degree required to induce a disruption in adhesion [46]. At higher densities (45% and 55% PIPAAm), the swelling provided by the increased amount of grafted PIPAAm that was not tightly bound to the PS substrate was apparently sufficient to induce disruption. However, at still higher densities (55% PIPAAm), adhesion was disrupted but the cell sheets did not detach intact. In this case, it is possible that grafted PIPAAm layer did not fully support uniform cell adhesion and growth, resulting in poor cell sheet formation. It is interesting to note that these results indicate that there is an optimum range of PIPAAm grafting density for PS substrates made with the method described in this paper (45-50%) that is slightly lower than what is typically used to graft TCPS culture dishes (53-55%) [46]. Since both microtextured and non-microtextured exhibited optimal thermally-induced cell detachment in the same range of IPAAm concentration, it is unlikely that this difference is attributable to the microtexturing itself. The nature of the surface of the PS films used here may have been different than TCPS, potentially resulting in differences in PIPAAm grafting density and/or thickness between the two types of substrates. Given the sensitivity of thermally-induced cell detachment on the thickness of the grafted PIPAAm layer, even small differences in substrate surface chemistry could result in changes to the functional thermoresponsive properties of the grafted substrates. Regardless of the mechanism, these results indicate that the optimum PIPAAm grafting density for cell sheet detachment must be determined whenever the substrate material is altered.

Transferring mature cell sheets from patterned substrates onto non-patterned substrates, other cell sheets, and ultimately to the tissue/organ of interest for in vivo repair/regeneration is a crucial aspect of cell sheet technology. Additionally, for the organized cells such as the ones created here, this transfer must occur while maintaining the organization of the sheets, otherwise this method of generating cell sheets will be rendered useless if the organization is lost following detachment. Cell sheets tend to contract considerably when detached from PIPAAm-grafted substrates [23, 48], which does not present a major problem for many applications employing isotropic cell sheets; however, in some cases it is desirable for the cell sheets to be used in their non-contracted form. For this reason, a simple method of sheet transfer has been previously developed [26]. Using a simple gelatin coated stamp to aid in the detachment of the cell sheets, this method has been used to easily transfer cell sheets from one substrate to another while maintaining the original dimensions of the sheets for the purpose of creating multilayer tissues comprised of several stacked cell sheets. This method has been effectively utilized here for the transfer of organized cell sheets to TCPS culture dishes without loss of cell organization, as evidenced by the maintenance of cell angle distribution and f-actin organization. More recently, a method to generate tubular tissues from cell sheets has been developed [49], which is useful to the development of arterial tissue. This technique further expands the array of cell sheet manipulation techniques that may be employed in order to form more complicated, multilayered organized tissues.

While these results are promising, considerable work remains in order to fully realize the potential of this system. The unique properties of tissues are strongly dictated by the quantity, composition, and organization of the ECM. As this study only focused on the short-term development of cell sheet on these substrates, we do not yet have any insight into the accumulation and organization of the cell-secreted matrix that will inevitably occur at longer times. It will be crucial to assess how the matrix is assembled as the sheets mature and whether the templating effect of the patterned substrates is maintained for long periods in culture as the sheets grow and thicken. Sheets retain their organization upon transfer to non-patterned surfaces, but the retention of this organization after an extended period in culture (weeks) has not been assessed. However, while cell and ECM organization are crucial to producing a tissue with anisotropic properties, they are not measures of tissue performance in and of themselves. To this end, sophisticated, highly sensitive mechanical testing techniques [50] will be required in order to assess the anisotropy (or lack thereof) of such aligned tissues. Our preliminary investigations (not shown) indicate that such organization can lead to sheets with desired mechanical anisotropy. Lastly, combining multiple cell sheets via stacking or rolling is an essential aspect of cell sheet technology as it allows for creation of larger, more complicated tissues. While this has not been demonstrated for the organized cell sheets produced in this study, there is considerable evidence in the literature that sheets can be readily stacked into a number of configurations using many different cell types [17], including smooth muscle cells [51], suggesting that this should not present a major challenge. Future studies with these organized sheets will focus on creating multilayer tissues with a complete analysis of their morphological, biological, and mechanical properties.

While the work presented in this study was introduced within the framework of developing a tissue engineered vascular graft, we feel that this approach can be broadly applied to a number of tissue engineering applications where cell sheet engineering would be beneficial and precise structural control of the sheets is desired. Cardiac tissue engineering for infarct repair is currently one of the most highly studied applications for cell sheet engineering [17]. The cardiac wall is comprised of multiple layers of highly aligned cardiac muscle, which allows for enhanced cell-cell interactions and greatly improves contraction efficiency. Producing an aligned cardiac patch that could mimic the proper structure of the native cardiac wall and provide enhanced contractile function would likely be a dramatic improvement for infarct repair. Skeletal muscle engineering would likely receive the same benefits from such an aligned construct [52]. While the parallel groove pattern is well suited for the blood vessel and muscle applications, the patterning of these substrates is not limited to such simple geometries. Heart valve tissue engineering is one such area where complicated substrate patterning could be employed to improve tissue properties [53]. The unusual shape of the heart valve and complicated matrix organization make it a challenging target for tissue engineering. However, precise control of tissue structure offered by the technique described in this study may offer the ability to produce valve-like tissues with the desired organization. These are but a few possible examples of tissue engineering applications that could benefit from this technique.

Conclusions

In this study, we have described a simple, effective method of producing cell sheets with defined organization using thermoresponsive, microtextured substrates. The microtexturing provided guidance cues that allowed for the precise control of cellular organization, while the PIPAAm-coating facilitated harvest of intact cells sheets by means of a simple change in culture temperature. Furthermore, the patterned cell sheets retained their organization upon removal from the microtextured substrates, indicating the microtexturing was not required to maintain the organization of the sheets. While only simple parallel groove patterns were investigated in this study, patterns are not limited to such simple geometries and can be as intricate as photolithographic techniques allow. We feel that this approach can be broadly applied to a number of tissue engineering applications where cell sheet engineering would be beneficial and precise structural control of the sheets is desired.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to specifically acknowledge Masumi Yamada, Ph.D. and Megumi Muraoka for their technical assistance. This work has been supported by NIH (HL 72900) (J.Y.W.) and Formation of Innovation Center for fusion of Advanced Technologies in the Special Coordination Funds for Promoting Science and Technology from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), Japan (T.O.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Fung YC. Biomechanics: Mechanical Properties of Living Tissues. New York: Spinger-Verlag; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Isenberg BC, Williams C, Tranquillo RT. Small-diameter artificial arteries engineered in vitro. Circ Res. 2006;98(1):25–35. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000196867.12470.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Teebken OE, Haverich A. Tissue engineering of small diameter vascular grafts. Eur J of Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2002;23(6):475–485. doi: 10.1053/ejvs.2002.1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmedlen RH, Elbjeirami WM, Gobin AS, West JL. Tissue engineered small-diameter vascular grafts. Clin Plast Surg. 2003;30(4):507–517. doi: 10.1016/s0094-1298(03)00069-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Canham PB, Talman EA, Finlay HM, Dixon JG. Medial collagen organization in human arteries of the heart and brain by polarized light microscopy. Connect Tissue Res. 1991;26(12):121–134. doi: 10.3109/03008209109152168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glagov S. Relation of structure to function in arterial walls. Artery. 1979;5(4):295–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolinsky H, Glagov S. Structural Basis For The Static Mechanical Properties Of The Aortic Media. Circ Res. 1964;14:400–413. doi: 10.1161/01.res.14.5.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rhodin J. Architecture of the vessel wall. In: Berne R, editor. Handbook of Physiology. Baltimore: Waverly Press, Inc.; 1980. pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barocas VH, Girton TS, Tranquillo RT. Engineered alignment in media equivalents: magnetic prealignment and mandrel compaction. J Biomech Eng. 1998;120(5):660–666. doi: 10.1115/1.2834759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.L'Heureux N, Germain L, Labbe R, Auger FA. In vitro construction of a human blood vessel from cultured vascular cells: a morphologic study. J Vasc Surg. 1993;17(3):499–509. doi: 10.1067/mva.1993.38251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grassl ED, Oegema TR, Tranquillo RT. A fibrin-based arterial media equivalent. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2003;66(3):550–561. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.10589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tower TT, Neidert MR, Tranquillo RT. Fiber alignment imaging during mechanical testing of soft tissues. Ann Biomed Eng. 2002;30(10):1221–1233. doi: 10.1114/1.1527047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Isenberg BC, Williams C, Tranquillo RT. Endothelialization and flow conditioning of fibrin-based media-equivalents. Ann Biomed Eng. 2006;34(6):971–985. doi: 10.1007/s10439-006-9101-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.L'Heureux N, McAllister TN, de la Fuente LM. Tissue-engineered blood vessel for adult arterial revascularization. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;357(14):1451–1453. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc071536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grenier G, Remy-Zolghadri M, Larouche D, Gauvin R, Baker K, Bergeron F, et al. Tissue reorganization in response to mechanical load increases functionality. Tissue Eng. 2005;11(12):90–100. doi: 10.1089/ten.2005.11.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Auger FA, Remy-Zolghadri M, Grenier G, Germain L. The Self-Assembly Approach for Organ Reconstruction by Tissue Engineering. e-biomed: The Journal of Regenerative Medicine. 2000;1(5):75–86. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang J, Yamato M, Shimizu T, Sekine H, Ohashi K, Kanzaki M, et al. Reconstruction of functional tissues with cell sheet engineering. Biomaterials. 2007;28(34):5033–5043. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.07.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Okano T, Yamada N, Okuhara M, Sakai H, Sakurai Y. Mechanism of cell detachment from temperature-modulated, hydrophilic-hydrophobic polymer surfaces. Biomaterials. 1995;16(4):297–303. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(95)93257-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heskins M, Guilent JE, James E. Solution properties of poly(Nisopropylacrylamide) J Macromol Sci A. 1968;2(8):1441–1455. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Canavan HE, Cheng X, Graham DJ, Ratner BD, Castner DG. Cell sheet detachment affects the extracellular matrix: a surface science study comparing thermal liftoff, enzymatic, and mechanical methods. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2005;75(1):1–13. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kushida A, Yamato M, Isoi Y, Kikuchi A, Okano T. A noninvasive transfer system for polarized renal tubule epithelial cell sheets using temperature-responsive culture dishes. Eur Cell Mater. 2005;10:23–30. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v010a03. discussion 23-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kushida A, Yamato M, Kikuchi A, Okano T. Two-dimensional manipulation of differentiated Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cell sheets: the noninvasive harvest from temperature-responsive culture dishes and transfer to other surfaces. J Biomed Mater Res. 2001;54(1):37–46. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(200101)54:1<37::aid-jbm5>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kushida A, Yamato M, Konno C, Kikuchi A, Sakurai Y, Okano T. Decrease in culture temperature releases monolayer endothelial cell sheets together with deposited fibronectin matrix from temperature-responsive culture surfaces. J Biomed Mater Res. 1999;45(4):355–362. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(19990615)45:4<355::aid-jbm10>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Canavan HE, Cheng X, Graham DJ, Ratner BD, Castner DG. Surface characterization of the extracellular matrix remaining after cell detachment from a thermoresponsive polymer. Langmuir. 2005;21(5):1949–1955. doi: 10.1021/la048546c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsuda Y, Kikuchi A, Yamato M, Nakao A, Sakurai Y, Umezu M, et al. The use of patterned dual thermoresponsive surfaces for the collective recovery as co-cultured cell sheets. Biomaterials. 2005;26(14):1885–1893. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsuda Y, Shimizu T, Yamato M, Kikuchi A, Sasagawa T, Sekiya S, et al. Cellular control of tissue architectures using a three-dimensional tissue fabrication technique. Biomaterials. 2007;28(33):4939–4946. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Desai TA. Micro- and nanoscale structures for tissue engineering constructs. Med Eng Phys. 2000;22(9):595–606. doi: 10.1016/s1350-4533(00)00087-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Curtis A, Wilkinson C. Topographical control of cells. Biomaterials. 1997;18(24):1573–1583. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(97)00144-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kane RS, Takayama S, Ostuni E, Ingber DE, Whitesides GM. Patterning proteins and cells using soft lithography. Biomaterials. 1999;20(2324):2363–2376. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(99)00165-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thakar RG, Ho F, Huang NF, Liepmann D, Li S. Regulation of vascular smooth muscle cells by micropatterning. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;307(4):883–890. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)01285-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen CS, Mrksich M, Huang S, Whitesides GM, Ingber DE. Micropatterned surfaces for control of cell shape, position, and function. Biotechnol Progr. 1998;14(3):356–363. doi: 10.1021/bp980031m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dusseiller MR, Schlaepfer D, Koch M, Kroschewski R, Textor M. An inverted microcontact printing method on topographically structured polystyrene chips for arrayed micro-3-D culturing of single cells. Biomaterials. 2005;26(29):5917–5925. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Feng J, Chan-Park MB, Shen JY, Chan V. Quick layer-by-layer assembly of aligned multilayers of vascular smooth muscle cells in deep microchannels. Tissue Eng. 2007;13(5):1003–1012. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.0223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sarkar S, Dadhania M, Rourke P, Desai TA, Wong JY. Vascular tissue engineering: microtextured scaffold templates to control organization of vascular smooth muscle cells and extracellular matrix. Acta Biomater. 2005;1(1):93–100. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilkinson CD. Making structures for cell engineering. Eur Cell Mater. 2004;8:21–25. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v008a03. discussion 25-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vernon RB, Gooden MD, Lara SL, Wight TN. Microgrooved fibrillar collagen membranes as scaffolds for cell support and alignment. Biomaterials. 2005;26(16):3131–3140. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Charest JL, Bryant LE, Garcia AJ, King WP. Hot embossing for micropatterned cell substrates. Biomaterials. 2004;25(19):4767–4775. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boland T, Xu T, Damon B, Cui X. Application of inkjet printing to tissue engineering. Biotechnol J. 2006 doi: 10.1002/biot.200600081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Odde DJ, Renn MJ. Laser-guided direct writing of living cells. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2000;67(3):312–318. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0290(20000205)67:3<312::aid-bit7>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pins GD, Bush KA, Cunningham LP, Campagnola PJ. Multiphoton excited fabricated nano and micro patterned extracellular matrix proteins direct cellular morphology. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2006;78(1):194–204. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xia Y, Whitesides G. Soft lithography. Ann Rev Mater Sci. 1998;28(1):153–184. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Russo AP, Apoga D, Dowell N, Shain W, Turner AMP, Craighead HG, et al. Microfabricated plastic devices from silicon using soft intermediates. Biomed Microdevices. 2002;4(4):277–283. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yamada N, Okano T, Sakai H, Karikusa F, Sawasaki Y, Sakurai Y. Thermoresponsive Polymeric Surfaces - Control of Attachment and Detachment of Cultured-Cells. Makromol Chem-Rapid. 1990;11(11):571–576. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dunn GA. Contact guidance of cultured tissue cells: a survey of potentially relevant properties of the substratum. In: Bellairs ACR, Dunn G, editors. Cell Behaviour. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1982. pp. 247–280. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tsuda Y, Kikuchi A, Yamato M, Chen G, Okano T. Heterotypic cell interactions on a dually patterned surface. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;348(3):937–944. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.07.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Akiyama Y, Kikuchi A, Yamato M, Okano T. Ultrathin poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) grafted layer on polystyrene surfaces for cell adhesion/detachment control. Langmuir. 2004;20(13):5506–5511. doi: 10.1021/la036139f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cheng X, Canavan HE, Stein MJ, Hull JR, Kweskin SJ, Wagner MS, et al. Surface chemical and mechanical properties of plasma-polymerized N-isopropylacrylamide. Langmuir. 2005;21(17):7833–7841. doi: 10.1021/la050417o. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kwon OH, Kikuchi A, Yamato M, Sakurai Y, Okano T. Rapid cell sheet detachment from poly(N-isopropylacrylamide)-grafted porous cell culture membranes. J Biomed Mater Res. 2000;50(1):82–89. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(200004)50:1<82::aid-jbm12>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kubo H, Shimizu T, Yamato M, Fujimoto T, Okano T. Creation of myocardial tubes using cardiomyocyte sheets and an in vitro cell sheet-wrapping device. Biomaterials. 2007;28(24):3508–3516. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Black LD, Brewer KK, Morris SM, Schreiber BM, Toselli P, Nugent MA, et al. Effects of elastase on the mechanical and failure properties of engineered elastin-rich matrices. JAppl Physiol. 2005;98(4):1434–1441. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00921.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang J, Yamato M, Kohno C, Nishimoto A, Sekine H, Fukai F, et al. Cell sheet engineering: recreating tissues without biodegradable scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2005;26(33):6415–6422. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.04.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rowlands AS, Hudson JE, Cooper-White JJ. From scrawny to brawny: the quest for neomusculogenesis; smart surfaces and scaffolds for muscle tissue engineering. Expert review of medical devices. 2007;4(5):709–728. doi: 10.1586/17434440.4.5.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mendelson K, Schoen FJ. Heart valve tissue engineering: concepts, approaches, progress, and challenges. Ann Biomed Eng. 2006;34(12):1799–1819. doi: 10.1007/s10439-006-9163-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]