Abstract

The mechanism of cytotoxicity of alemtuzumab and rituximab in CLL is not well understood. We obtained fresh CLL cells from early stage high risk patients just prior to treatment with alemtuzumab and rituximab to study mechanisms of action and resistance. Alemtuzumab had minimal direct cytotoxicity but caused significant complement dependent cytotoxicity (CDC) although a subpopulation of CLL cells had intrinsic resistance. Rituximab had no direct cytotoxicity and caused minimal CDC in cells from most patients. These data suggest that CDC has a therapeutic role in patients treated with alemtuzumab and that measures to decrease resistance to CDC could increase efficacy.

Keywords: Chronic lymphocytic leukemia, CLL, lemtuzumab, rituximab, complement, cytotoxicity

Introduction

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is the most prevalent lymphoid malignancy in North America and Europe and is still incurable with conventional therapy1, 2. However, a better understanding of the biology of CLL and the development of new classes of drugs could lead to improved and individualized management. Improvements in prognostication now allow us to identify early stage patients with a high risk of rapid disease progression and shorter survival 3. In these patients, early administration of targeted therapeutic monoclonal antibodies (MoAb) has the potential to alter the clinical course of their CLL. We recently conducted a phase II study of treatment of high risk early stage CLL with a regimen combining alemtuzumab and rituximab. The rationale for this approach was that patients with biological features predictive of high risk of disease progression could benefit from early treatment with MoAb therapy which is most effective when tumor burden is low. In addition, alemtuzumab is known to have activity for those high risk patients with deletion of 17p13 (17p13-) whose disease is frequently resistant to purine analogue therapy4. To further explore the mechanism of action and resistance of alemtuzumab and rituximab in CLL, we prospectively studied the association of the in vitro response of fresh CLL cells collected prior to treatment from the patients participating in this trial with their clinical response.

Our study shows that alemtuzumab complement dependent cytotoxicity (CDC) kills the majority of CLL cells in vitro but that some of the surviving cells have intrinsic resistance to complement lysis. Rituximab CDC was minimal in most patients and the addition of rituximab did not significantly increase alemtuzumab CDC suggesting other mechanisms, such as anti-body dependent cytotoxicity (ADCC), may play a role in rituximab mediated cytotoxicity. These data support an important role for alemtuzumab CDC in the treatment of CLL and suggest that a better understanding of the exact mechanism(s) of resistance of CLL cells to alemtuzumab CDC could be of clinical value.

Methods and Materials

Patients

The study was conducted at Mayo Clinic Rochester with the approval of the Institutional Review Board. The clinical study enrolled 30 previously untreated patients with high risk CLL defined as at least one of the following 1) 17p13-; 2)11q22-; and 3) unmutated IgVH together with ZAP-70+ and/or CD38+. All patients had early to intermediate stage disease (Rai 0 – II5) and did not meet the National Cancer Institute Working Group of 1996 (NCI-WG 96)6 criteria for treatment of their CLL. Patients were treated a median of 0.6 years (0.1 – 6.1 years) after diagnosis with a 31 day regimen of subcutaneous alemtuzumab (30 mg subcutaneous injection three times a week) and intravenous rituximab (375 mg/m2/week). Response to treatment was determined using the NCI-WG 96 criteria at 2 months after completion of therapy.

In vitro testing

In vitro studies were successfully performed on fresh blood specimens from 27 patients of the 30 patients treated on the clinical trial. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated from 20ml of heparinized whole blood by density gradient centrifugation using Ficoll-Paque PLUS (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences AB, Uppsala, Sweden). The percentage of B cells in specimens was measured by staining for CD19 (median cell purity was 89%, range 66 – 99%). PBMC were assayed by flow cytometry for expression of CD3, CD4, CD5, CD8, CD14, CD16, CD19, CD20, CD 79b (BD Biosciences, San Jose, California, USA), CD52 (AbD Serotec, Kidlington, Oxford, UK), CD55 and CD59 (BD Bioscience Pharmingen, San Jose, CA, USA). The expression of antigen was determined by measuring the difference in mean channel fluorescence of positive staining cells compared to isotype controls (delta MFI). Patient cells were cultured in AIM V medium (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) at 2 × 106/ml at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2. Cytotoxicity assays were performed as previously described7. In our experiments, the alemtuzumab (CAMPATH 1H, Berlex Laboratories, Richmond, CA) was used at 10 µg/ml, rituximab (Genentec, Inc., South San Francisco, CA, USA) at 20 µg/ml, and F-ara-A (2-fluoroadenine-9-β-D-arabinofuranoside) (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA) the active metabolite of fludarabine, at 3 µM. Human serum complement (Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO, USA) containing 40 CH50 units/ml, was used at a 10% (v/v) dilution as a source of complement. For studies of complement dependent cytotoxicity, CLL cells were pre-incubated with MoAb for 30 minutes on ice prior to adding complement and warming to 37°C at time 0. For experiments to determine alemtuzumab CDC in cells surviving initial treatment, intact cells were separated by density centrifugation, viable cells were then counted using trypan blue staining and resuspended in AIM V medium at 2 × 106 viable cells/ml. To test for the complement metabolite iC3b deposition on CLL cells after treatment with rituximab and complement, cells were stained with a anti-iC3b monoclonal (Quidel, San Diego, CA) and expression evaluated by flow cytometry.

Cell survival after treatment with MoAb was evaluated by cell counting and flow cytometry. Cell counts (minimum count of 200 cells/sample) were performed after staining cells with a 50:50 mixture of 0.4% trypan blue (Sigma-Aldrich Co.) using a standard counting chamber and microscope with 40x objective lens. Cells that excluded trypan blue were considered to be viable. Apoptosis was measured by flow cytometry using Annexin V (Caltag Laboratories,Carlsbad, CA, USA) and loss of cell membrane integrity measured by propidium iodide (PI) (Sigma-Aldrich Co.) permeability, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Flow cytometry analysis was performed on the FACScan (Beckton Dickinson, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) and 10,000 events per sample were analyzed using CellQuestPro Software (BD Biosciences).

Data analysis

Relationships between continuous variables were evaluated using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient. The Wilcoxon rank sum and Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to assess the relationship between continuous measures and categorical variables. In addition, the Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to evaluate the relationship between paired values. Duration of response was defined as the time from the date a response was achieved to the date of disease progression. Time to progression was defined as the time from the date of registration on the clinical study to the date of disease progression. Univariate Cox models were used to evaluate the relationship of alemtuzumab CDC with duration of response and time to progression. All tests were two-sided and statistical significance was defined as p<0.05. To represent the data in figures, boxplots were constructed using the five-number summary for each measure (the smallest observation, the 25th percentile, the median, the 75th percentile, and the largest observation), with outliers indicated by plus signs.

Results

Alemtuzumab and rituximab are not directly toxic to CLL cells

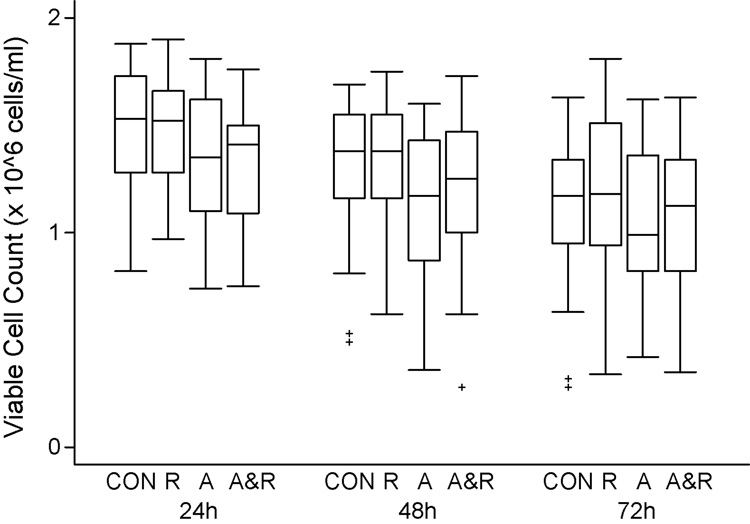

Our previous studies have suggested that alemtuzumab causes little or no apoptosis in CLL cells cultured in serum free medium7. In this study, we measured the number of viable cells (trypan blue negative) in cultures with alemtuzumab, rituximab, and alemtuzumab and rituximab. As shown in figure 1, rituximab had no effect on CLL survival compared to control cells. Cells treated with alemtuzumab and the combination of alemtuzumab and rituximab had a slightly decreased survival compared to control cells which was significant for alemtuzumab at 24 hours (p=0.05) and 48 hours (p=0.0008) compared to control. However at 72 hours of culture this difference was no longer significant (p=0.36)(figure 1). These data suggest that direct cytotoxicity is unlikely to be a clinically important mechanism of action of these MoAb in CLL.

1. Alemtuzumab and rituximab are not toxic to CLL cells in culture.

CLL cells at 2 × 106/ml were cultured with either alemtuzumab (10 µg/ml)(A), rituximab (20 µg/ml)(R), or alemtuzumab and rituximab (A&R) at the same concentrations. Viable cell (trypan blue negative) counts were evaluated every 24 hours for 72 hours. These data demonstrate that cells cultured with rituximab have identical survival to control cells (CON) cultured in AIM V medium. Cells cultured with alemtuzumab or alemtuzumab and rituximab have slightly lower survival.

Alemtuzumab CDC is highly effective against CLL cells

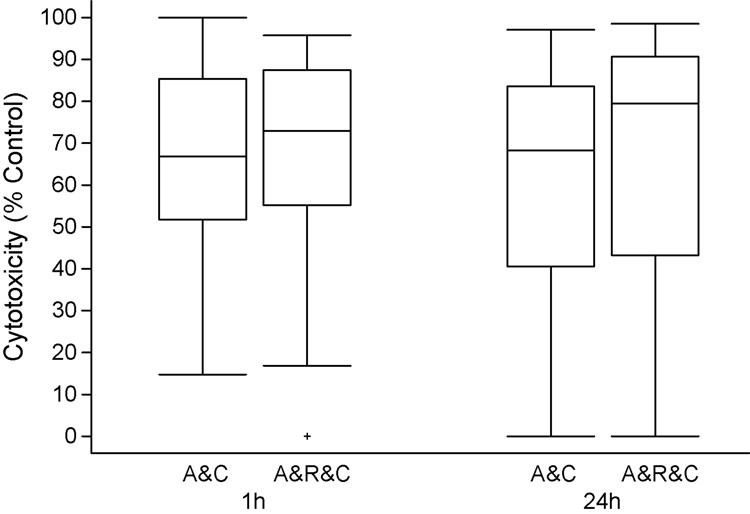

Alemtuzumab CDC was measured as the percentage cytotoxicity 1 hour after treatment of fresh CLL cells with alemtuzumab (10 µg/ml) and 10% human serum as a source of complement compared to control cells cultured in 10% human serum alone. As shown in Figure 2, median alemtuzumab CDC at 1 hour was 67% (range 15 – 100%). No increase in cell death was observed after 24 hour culture with alemtuzumab and complement indicating alemtuzumab induced CDC occurred rapidly. In contrast the median decrease in viable cell count in samples treated with rituximab and complement was only 2% (range 0 – 48%, data not shown). Only 6 patient samples treated with rituximab and complement had > 10% cytotoxicity (median 23%, range 14 – 48). We next explored the effect of the rituximab-alemtuzumab combination. CDC was not significantly increased by the addition of rituximab to alemtuzumab (p = 0.20, median cytotoxicity 73% at 1 hour, range 0 – 96%) (Figure 2). The 6 samples with appreciable rituximab CDC had no increase in CDC with alemtuzumab and rituximab compared to alemtuzumab alone (p > 0.10). These data indicate that there is appreciable alemtuzumab CDC, suggesting that this is an important mechanism of action for alemtuzumab in the treatment of CLL. In contrast, CDC does not appear to be an important mechanism of rituximab induced cell death for most patients with CLL.

2. Alemtuzumab complement dependent cytotoxicity (CDC) induces rapid cytotoxicity of CLL cells.

CLL cells at a concentration of 2 × 106/ml were treated with alemtuzumab (10µg/ml) and 10% human serum as a source of complement. Cytotoxicity was determined by counting the number of viable cells (trypan blue negative) 1 hour after treatment. These values were normalized using the counts in control cell cultures treated with complement only. These studies showed that alemtuzumab CDC (A&C) killed a median of 67% (range 15 – 100%) of the CLL cells from 27 patients within 1 hour. The cells surviving CDC did not have an increased rate of death during the subsequent 23 hours. Addition of rituximab to alemtuzumab (A&R&C) did not significantly increase CDC (p = 0.20).

To evaluate if MoAb induced CDC caused changes in the CLL cell membrane resulting in delayed cell lysis or apoptosis, the test cultures described above were continued for an additional 2 days after measurement of 24 hour CDC. Viable cell counts (Figure 3) and annexin/PI staining flow cytometry analysis (data not shown) demonstrated that there was no additional apoptosis or cell lysis observed during this time. In alemtuzumab and complement treated cells, the median decrease in viable cell counts (corrected for control cells) was 67% at 1 hour versus 68% at 72 hours (p = 0.91). These data suggest that alemtuzumab CDC occurs rapidly in vitro and that cells surviving alemtuzumab CDC have equivalent subsequent survival in vitro compared to control cells.

3. The subpopulation of CLL cells that survive alemtuzumab CDC remains viable for 72 hours.

CLL cells at 2 × 106/ml were treated with alemtuzumab (10µg/ml) and 10% human serum as a source of complement and cultured for 72 hours. These assays showed that cells surviving initial CDC caused by alemtuzumab (A&C) or the combination of alemtuzumab and rituximab (A&R&C) had the same survival as cells treated with complement alone (C).

Alemtuzumab CDC was also measured by assessing changes in cell permeability to PI by flow cytometry. The correlation between cytotoxicity measured by viable cell counts (trypan blue negative) and the percentage of PI permeable cells was moderate (r = 0.52, p=0.006), However, when the comparison was restricted to specimens with less than a 50% decrease in cell counts after treatment with alemtuzumab and complement (n = 21), the correlation was markedly improved (r = 0.81, p<0.0001). This difference is due to the inability of conventional flow cytometry to detect CLL cells that are lysed by alemtuzumab CDC. These findings reinforce the need to measure both cell number and viability after treatment with alemtuzumab and complement.

To determine if the level of target antigen expression by CLL cells predicts CDC, we measured the delta MFI expression of CD52 and CD20 on CLL cells prior to treatment. CD52 was expressed in CD19+ cells with a median delta MFI of 297 (range 63 – 924). There was no correlation between the intensity of expression of delta CD52 and alemtuzumab CDC (r = −0.24, p = 0.22). Median CD20 delta MFI was 71 (range 8 – 295). The six patient samples with rituximab CDC >10% did not have significantly higher CD20 delta MFI compared to those specimens with < 10% rituximab CDC (p = 0.19). These data show that there is little correlation in these CLL cells between the level of expression of target antigen and MoAb induced CDC and suggests that in CLL cells, antigen density is not likely to be a major factor in determining the extent of alemtuzumab or rituximab CDC.

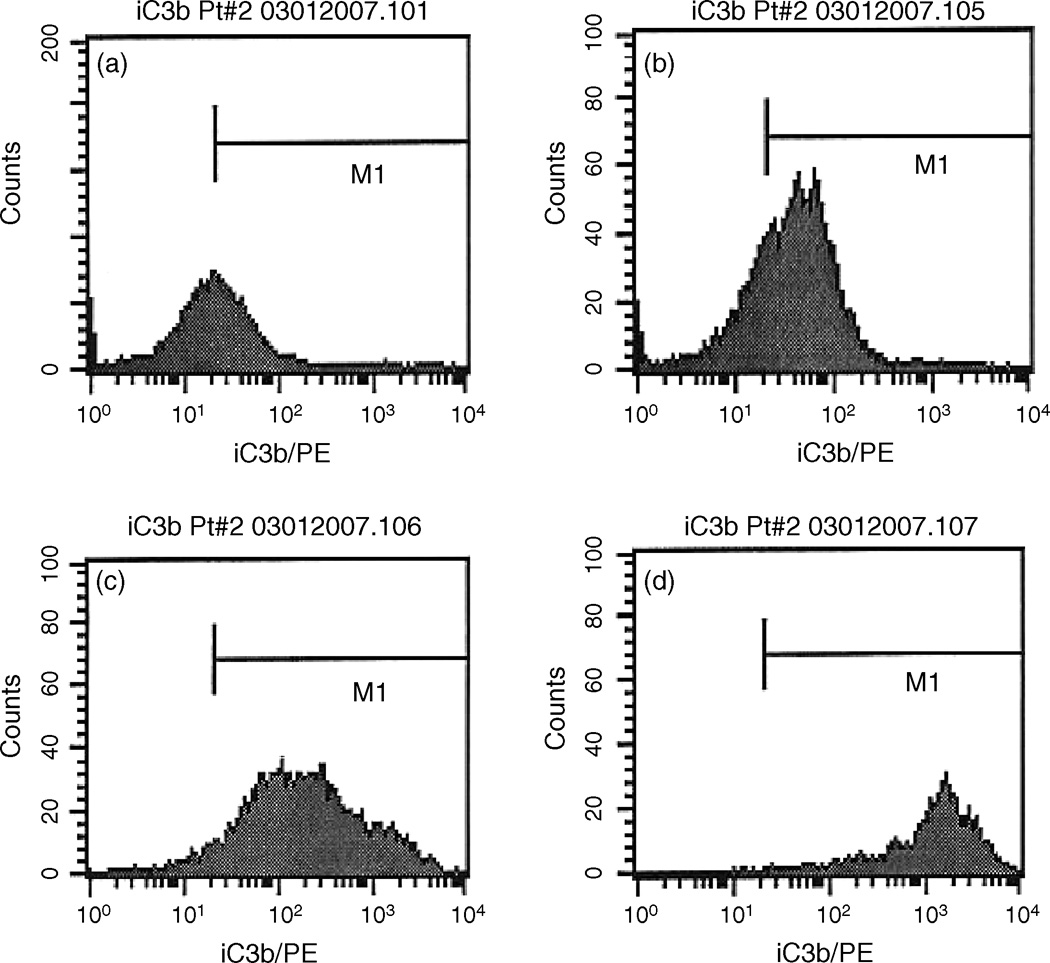

To show that rituximab can activate complement in these assays, 2 patient specimens with low levels of rituximab CDC were evaluated for iC3b binding. As shown for a representative patient in Figure 4, CLL cells treated with rituximab and complement had increased levels of iC3b compared to cells treated with complement alone. The highest expression of membrane iC3b was detected in viable CLL cells that had not been lysed after exposure to alemtuzumab and complement. These data show that both rituximab and alemtuzumab can activate complement on the surface of CLL cells. However levels of complement activation are higher on CLL cells that survive alemtuzumab CDC.

4. Cells treated with MoAb and complement had increased membrane iC3 binding.

Membrane bound iC3b was measured in CLL cells by flow cytometry with an anti-iC3b antibody. Control CLL cells in AIM V medium stained with anti-iC3b antibody are shown in panel a. Addition of 10% serum (4U/ml complement) resulted in a modest increase in MFI (from 20 to 36)(panel b). Addition of both rituximab and complement (panel c) resulted in an increase in MFI to 201. In this experiment, the highest level of iC3b was measured in cells surviving treatment with alemtuzumab and complement (panel d) which had a MFI of 1129.

Intrinsic resistance to alemtuzumab CDC in a subpopulation of CLL cells

The factors contributing to the resistance of some cells to alemtuzumab CDC in vitro could include limiting amounts of reagents (alemtuzumab or complement) and intrinsic resistance of a subpopulation of CLL cells to alemtuzumab CDC. In preliminary experiments prior to this study, alemtuzumab CDC assays were done on CLL cells using alemtuzumab at concentrations of 0.5 – 50 µg/ml and Human Serum Complement (complement) at concentrations of 1 – 50% (volume/volume) to determine optimal concentrations of both reagents (data not shown). In these studies, the CDC reached a plateau at an alemtuzumab concentration of 5µg/ml and serum concentration of 5%. These data suggest that in the experiments done in this study using alemtuzumab at 10µg/ml and a 10% concentration of human serum as a source of complement, neither reagent should have been limiting achievement of maximal CDC.

To determine if a subpopulation of CLL was resistant to alemtuzumab CDC, we isolated the residual viable CLL cells surviving alemtuzumab CDC and repeated the treatment with alemtuzumab and complement. Experiments were performed on samples from 18 patients. Samples from 3 specimens had very high initial alemtuzumab CDC (91 – 100%) and there were insufficient residual viable cells for retreatment. Three specimens with very low initial alemtuzumab CDC (19 – 28%) had minimal change on retesting and were excluded from the data analysis. Twelve patient samples were sensitive (> 30% cytotoxicity) to alemtuzumab CDC with sufficient surviving cells for retreatment. In these samples, median initial alemtuzumab CDC was 76% (range 53 – 88%) and decreased to a median of 51% (range 6 – 78%) (p ≤ 0.01) with retreatment. These data suggested that a subpopulation of CLL cells do indeed have intrinsic resistance to alemtuzumab CDC.

The CLL cells were then tested for expression of factors known to affect sensitivity to CDC. CD55 and CD59 are membrane complement regulatory proteins (mCRP) that can inhibit CDC8. The expression of CD55 and CD59 was measured on CD19 positive cells prior to treatment with MoAb. Median CD55 delta MFI was 69 (range 40 – 737). Median CD59 delta MFI was 95 (range 39 – 337). There was no correlation between the expression of delta MFI of either CD55 or CD59 and % alemtuzumab CDC (r = −0.04, p = 0.85 for CD55 delta MFI; r = 0.16, p = 0.43 for CD59 delta MFI). There was no relationship between CD55 or CD59 MFI expression and the achievement of CR to treatment using NCI-WG96 criteria. These data suggest that mCRP do not have an important role in the resistance of CLL cells to alemtuzumab CDC.

Alemtuzumab CDC is effective against 17p13-CLL cells resistant to F-ara-A

In vitro alemtuzumab CDC was compared to prognostic factors derived from interphase FISH for known chromosomal abnormalities, IgVH mutation status, and expression of CD38 and ZAP-70. Significantly increased alemtuzumab CDC occurred in patients who had 12+ (+/−13q14-) as the only FISH abnormalities (n = 7, median 88%, range 69 – 100%) compared to those who didn’t (median 61%, range 15 – 88%), p = 0.002). Significantly increased alemtuzumab CDC also occurred in patients with ≥ 30% cells positive for expression of CD38 (n = 11, median 80%, range 46 –100%) compared to CD38 negative patients (median 61%, range 15–88%), p=0.02. There was no correlation between any other measured prognostic factors and alemtuzumab CDC. In particular alemtuzumab CDC did not correlate with the presence of 17p13-(median cytotoxicity 61% vs 71%, p=0.28). Because cells with 17p13-are reported to have increased resistance to F-ara-A4, we compared alemtuzumab CDC at 1 hour to F-ara-A cytotoxicity at 72 hours. Although the median cytotoxicity was similar (67 vs. 78%), there was only a moderate correlation between sensitivity to alemtuzumab CDC and F-ara-A for individual specimens (r = 0.55)(p = 0.003). In patients with 17p13-, there was significantly increased resistance to F-ara-A (median 47% cytotoxicity, range 8 – 64%) compared to patients who did not have 17p13-(median 90% cytotoxicity, range 37 – 100%), p=0.0004. These data show that alemtuzumab CDC is not decreased by 17p13-and could be increased in CLL cells that have 12+ FISH or those positive for expression of CD38.

In vitro alemtuzumab CDC and clinical response

Alemtuzumab CDC in vitro measured at 1 hour was compared to patients’ clinical response evaluated 2 months after completion of therapy. Patients achieving a complete response (CR) by NCI-WG 96 criteria (n = 10) had a median alemtuzumab CDC of 74% (range 53 – 100%) compared to 57% (range 15 – 97%) for patients that did not achieve a CR. This difference did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.13). The level of in vitro alemtuzumab CDC also did not predict achievement of a CR with no residual CLL on immunohistochemical analysis of the bone marrow. Alemtuzumab CDC in vitro was not a significant predictor of either duration of response in the 26 responders (p=0.09) or time to progression in all 27 patients (p=0.13).

Alemtuzumab CDC in vitro was also compared to the decrease in blood absolute lymphocyte counts after the 4 doses of alemtuzumab given in the first week of therapy (median 97.4%, range 49.4 – 100%). There was no association found between these two values (r = 0.32, p = 0.10). Alemtuzumab CDC was then compared to the biological prognostic factors used in a hierarchical manner to stratify risk of disease progression (17p13- > 11q22- > unmutated IgVH with CD38+ and/or ZAP70+). Again there was no significant association with these risk factors and alemtuzumab CDC.

Discussion

The mechanism of action of both alemtuzumab and rituximab in patients with CLL remains uncertain. The results of this prospective study provide novel data using fresh CLL cells obtained from a population of previously untreated patients with a defined high biological risk CLL receiving a monoclonal antibody therapy. Our studies show that most CLL cells are rapidly killed by alemtuzumab CDC in vitro and that the surviving cells have some intrinsic resistance to complement lysis.

Our data confirm the finding of previous studies that alemtuzumab causes little to no direct cytotoxicity in CLL cells unless cross linking antibodies or F(ab)2 are used7, 9, 10.Previous studies have also shown that rituximab has no direct cytotoxic effect on CLL cells in vitro in the absence of cross linking10–12. Because ligation of CD52 and CD20 by these MoAb does not cause apoptosis in CLL cells, the principal mechanisms of action of these antibodies is more likely to require complement activation and cellular cytotoxicity.

The IgG1 constant region (Fc) common to alemtuzumab and rituximab can fix complement resulting in CDC. In this study, alemtuzumab caused rapid CDC which killed the majority of CLL cells in vitro. This suggests that CDC could be a clinically important mechanism of action for alemtuzumab and could be responsible for the rapid clearance of circulating CLL cells in patients treated with alemtuzumab. In contrast, rituximab CDC was less effective in CDC assays in vitro with only a minority of patient specimens having appreciable cytotoxicity. In this study, the average density of CD52 and CD20 as measured by flow cytometry did not correlate with the effectiveness of CDC and availability of MoAb and complement were unlikely to be rate limiting factors. In addition, there was no significant increase in CDC when rituximab was added to alemtuzumab, suggesting that additional antibody binding did not increase cytotoxicity. These findings do not preclude the possibility that in vivo rituximab can sensitize CLL cells to other drugs by an as yet unknown mechanism. We conclude that alemtuzumab CDC is likely to contribute to the clinical efficacy of alemtuzumab but there is no evidence to support a role of CDC as an important mechanism of action of rituximab in CLL.

The experiments reported in this study show that in most patients a subpopulation of CLL cells were resistant to alemtuzumab CDC. The results of retreatment of these surviving cells suggest that some of these cells could have intrinsic resistance to in vitro alemtuzumab CDC. Although the average level of expression of CD52 by the CLL cells measured prior to any treatment did not predict the effectiveness of alemtuzumab CDC, the level of expression of CD52 could be lower in surviving cells than susceptible cells and this will be measured in planned future studies. Measurement of the level of iC3b in cells surviving alemtuzumab CDC shows that these cells survived despite effective complement activation. Possible explanations include insufficient complement activation and increased activity of complement resistance factors. Although the pre-treatment level of expression of the mCRP CD55 and CD59 by the CLL cells did not predict resistance to alemtuzumab CDC, measurement of expression of these mCRP on surviving CLL cells would better determine the role of these proteins in resistance to alemtuzumab CDC and such studies are planned. Understanding the mechanism of resistance to CDC in CLL cells will thus require additional studies that should provide data crucial for overcoming CDC resistance and improving treatment response.

There is now substantial data suggesting that ADCC is a major mechanism of action of rituximab13. Our finding that rituximab is not directly cytotoxic to CLL cells and causes minimal CDC in CLL cells from most patients, would be compatible with ADCC being a major mechanism of action for rituximab in CLL. The lack of correlation between alemtuzumab CDC and clinical response could also reflect an important role for ADCC in the mechanism of action of alemtuzumab in vivo. Although direct CDC does not appear to play a role in rituximab mediated cytotoxicity, there is increasing data to suggest that deposition of complement protein fragments on the cell membrane after treatment with rituximab could enhance cellular cytotoxicity13. Our finding of increased levels of iC3b on cells treated with rituximab and complement and cells surviving alemtuzumab CDC suggests that these complement fragments could increase complement dependent cellular cytotoxicity. For example, this cytotoxicity could be enhanced by biological response modifiers such as yeast cell wall derived β-glucan which increase CR3 binding to iC3b14. Targeting complement components on cells surviving CDC could provide a novel method of increasing the clinical efficacy of alemtuzumab therapy.

Based on our trial design, this study population was enriched (30%) for patients with 17p13-which is associated with decreased p53 activity and a poor clinical response to treatment with purine analogue based therapy15, 16. In this study cells from patients with 17p13-had the predicted decreased sensitivity to F-ara-A in vitro but retained sensitivity to alemtuzumab CDC. In contrast, patients with 12+ (+/− 13q14-) as their only abnormality on FISH and those with membrane expression of CD38 exhibited higher levels of alemtuzumab CDC. The clinical significance of these findings will be studied further in planned trials.

The clinical trial from which these samples were derived also allowed us to examine the correlation between in vitro drug sensitivity and clinical responses to the MoAb combination. Because the overall response rate was 96%, the comparison was restricted to those patients who achieved CR versus those that did not achieve CR. Patients with a CR did indeed have higher levels of alemtuzumab CDC although this was not statistically significant. In addition, alemtuzumab CDC did not predict duration of response. The failure to demonstrate a significant relationship between alemtuzumab CDC and clinical response may be due to the small sample size and the limitations of the in vitro model of testing. Alternatively, failure to show a significant correlation could reflect the role of other important mechanisms of action such as ADCC. There is strong clinical data suggesting that the combination of alemtuzumab and rituximab could be more efficacious than alemtuzumab alone17, 18. Our finding that rituximab did not increase alemtuzumab CDC suggests that any clinical improvement in activity of alemtuzumab activity by rituximab is mediated by other mechanisms. The lack of significant correlation between our in vitro and clinical results emphasizes the need for a better understanding of the mechanisms of action of these therapeutic MoAb.

Conclusions

These in vitro studies, done in correlation with a clinical trial, provide data suggesting that CDC is an important mechanism of action for alemtuzumab but not rituximab. Efficacy of alemtuzumab could be limited by the existence of a subpopulation of CLL cells resistant to alemtuzumab CDC, and overcoming this resistance could improve clinical outcome. Neither alemtuzumab nor rituximab is directly toxic to CLL cells. Our findings suggest that the clinical efficacy of alemtuzumab could be improved by measures to overcome resistance to CDC. A better understanding of how these drugs mediate ADCC and complement mediated cellular toxicity could lead to interventions that could greatly improve their clinical value.

Acknowledgments

Support

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health - National Cancer Institute University of Iowa/Mayo Clinic SPORE Grant CA97274 and R01 grant CA95241, Bayer Health Care Pharmaceuticals, and Genentech.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Zent CS, Kyasa MJ, Evans R, Schichman SA. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia incidence is substantially higher than estimated from tumor registry data. Cancer. 2001;92:1325–1330. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010901)92:5<1325::aid-cncr1454>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morton LM, Wang SS, Devesa SS, Hartge P, Weisenburger DD, Linet MS. Lymphoma incidence patterns by WHO subtype in the United States, 1992–2001. Blood. 2006;107:265–276. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zent CS, Call TG, Hogan WJ, Shanafelt TD, Kay NE. Update on risk-stratified management for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2006;47:1738–1746. doi: 10.1080/10428190600634036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lozanski G, Heerema NA, Flinn IW, Smith L, Harbison J, Webb J, et al. Alemtuzumab is an Effective Therapy for Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia with p53 Mutations and Deletions. Blood. 2004;103:3278–3281. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-10-3729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rai KR, Sawitsky A, Cronkite EP, Chanana AD, Levy RN, Pasternack BS. Clinical staging of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 1975;46:219–234. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-08-737650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheson BD, Bennett JM, Grever M, Kay N, Keating MJ, O'Brien S, et al. National Cancer Institute-Sponsored Working Group guidelines for chronic lymphocytic leukemia: Revised guidelines for diagnosis and treatment. Blood. 1996;87:4990–4997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zent CS, Chen JB, Kurten RC, Kaushal GP, Lacy HM, Schichman SA. Alemtuzumab (CAMPATH 1H) does not kill chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells in serum free medium. Leuk Res. 2004;28:495–507. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2003.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Golay J, Zaffaroni L, Vaccari T, Lazzari M, Borleri GM, Bernasconi S, et al. Biologic response of B lymphoma cells to anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody rituximab in vitro: CD55 and CD59 regulate complement-mediated cell lysis. Blood. 2000;95:3900–3908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nuckel H, Frey UH, Roth A, Duhrsen U, Siffert W. Alemtuzumab induces enhanced apoptosis in vitro in B-cells from patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia by antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity. Eur J Pharmacol. 2005 May 9;514(2–3):217–224. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stanglmaier M, Reis S, Hallek M. Rituximab and alemtuzumab induce a nonclassic, caspase-independent apoptotic pathway in B-lymphoid cell lines and in chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells. Ann Hematol. 2004;83:634–645. doi: 10.1007/s00277-004-0917-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Byrd JC, Kitada S, Flinn IW, Aron JL, Pearson M, Lucas D, et al. The mechanism of tumor cell clearance by rituximab in vivo in patients with B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia: evidence of caspase activation and apoptosis induction. Blood. 2002;99:1038–1043. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.3.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pedersen I, Buhl A, Klausen P, Geisler C, Jurlander J. The chimeric anti-CD20 antibody rituximab induces apoptosis in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells through a p38 mitogen activated protein-kinase-dependent mechanism. Blood. 2002;99:1314–1319. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.4.1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glennie MJ, French RR, Cragg MS, Taylor RP. Mechanisms of killing by anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies. Mol Immunol. 2007 Sep;44:3823–3837. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2007.06.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ross GD, Vetvicka V, Yan J, Xia Y, Vetvickova J. Therapeutic intervention with complement and beta-glucan in cancer. Immunopharmacology. May;1999(42):61–74. doi: 10.1016/s0162-3109(99)00013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grever MR, Lucas DM, Dewald GW, Neuberg DS, Reed JC, Kitada S, et al. Comprehensive assessment of genetic and molecular features predicting outcome in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: results from the US Intergroup Phase III Trial E2997. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:799–804. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.3089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Catovsky D, Richards S, Matutes E, Oscier D, Dyer MJ, Bezares RF, et al. Assessment of fludarabine plus cyclophosphamide for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (the LRF CLL4 Trial): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;370:230–239. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61125-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Faderl S, Thomas DA, O'Brien S, Garcia-Manero G, Kantarjian HM, Giles FJ, et al. Experience with alemtuzumab plus rituximab in patients with relapsed and refractory lymphoid malignancies. Blood. 2003;101:3413–3415. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-07-1952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zent CS, Call TG, Shanafelt TD, Jelinek DF, Tschumper RC, Secreto CR, et al. Alemtuzumab and rituximab for initial treatment of high risk, early stage chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) Blood. 2007;110:611a. [Google Scholar]