Abstract

RNase P is the ubiquitous ribonucleoprotein metalloenzyme responsible for cleaving the 5′-leader sequence of precursor tRNAs during their maturation. While the RNA subunit is catalytically active on its own at high monovalent and divalent ion concentration, four proteins subunits are associated with archaeal RNase P activity in vivo: RPP21, RPP29, RPP30 and POP5. These proteins have been shown to function in pairs: RPP21-RPP29 and POP5-RPP30. We have determined the solution structure of RPP21 from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus (Pfu) using conventional and paramagnetic NMR techniques. Pfu RPP21 in solution consists of an unstructured N-terminus, two alpha helices, a zinc binding motif, and an unstructured C-terminus. Moreover, we have used chemical shift perturbations to characterize the interaction of RPP21 with Pfu RPP29. The data show that the primary contact with RPP29 is localized to the two helices of RPP21. This information represents a fundamental step towards understanding structure-function relationships of the archaeal RNase P holoenzyme.

Ribonuclease P (RNase P) is a ribonucleoprotein enzyme that is essential in all three domains of life for cleaving the 5′-leader sequence of precursor tRNA molecules (ptRNA) (1–3). In archaea, the catalytic RNA subunit (RPR) is associated with four protein subunits (RPPs) homologous to four eukaryotic nuclear RNase P proteins: RPP21, RPP29, RPP30 and POP5 (4). For RNase P from the hyperthermophilic archaeon, Pyrococcus furiosus (Pfu), robust ptRNA cleavage activity can be reconstituted from in vitro assembly of transcribed RPR and the four recombinantly expressed and purified RPPs (5). These four proteins appear to function in pairs (5), as the heterodimers RPP21-RPP29 or RPP30-POP5 can activate the RNA subunit at relatively low salt concentrations, while addition of either RPP21 or RPP29 to the RPP30-POP5 pair (or vice versa) does not significantly increase activity. These reconstitution data, together with the results from yeast two-hybrid experiments on archaeal and yeast homologs (6–8), suggest that RPP21 and RPP29 (as well as RPP30 and POP5) associate to promote RNase P holoenzyme assembly. Furthermore, recombinantly expressed human RPP21 was found to bind ptRNA (9), and RPP21 and RPP29 together were shown to functionally reconstitute the activity of human RNase P RNA (10), underscoring the evolutionary conservation of these important protein-protein and protein-RNA interactions. To gain insights into the structure and function of the RNase P holoenzyme, we have been investigating the three dimensional structures of the individual subunits, and report here the solution structure of Pfu RPP21.

Pfu RPP21 is a 117-residue protein that is highly conserved both within and between Archaea and Eukarya (Figure 1). Sequence analysis suggested that the protein contains a zinc-ribbon motif (11) featuring four invariant cysteine residues. Structure determination of Pfu RPP21 is an important step towards a structural model of the RNase P holoenzyme. Previously, we determined the solution structure of Methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus RPP29 by NMR (12) and the structure of P. furiosus POP5 by x-ray crystallography (13, 14). The crystal structures of P. horikoshii RPP30 (14, 15) and RPP21 (16) have also been reported. While determining the structures of the individual RPPs represents a crucial for understanding their roles within the holoenzyme, establishing how they interact with each other will provide greater insight into their role in RNA catalysis.

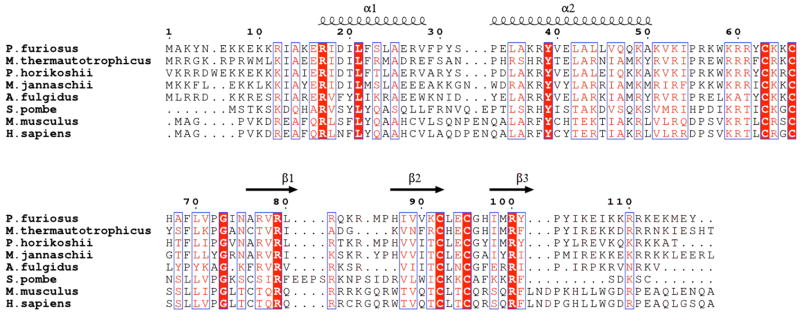

Figure 1.

Sequence alignment of RPP21 homologs from Archaea and Eukarya. Alignment was generated with CLUSTALW (47). Red lettering indicates a global similarity score of 0.7 while red boxes indicate invariant residues. Secondary structural elements observed in the NMR ensemble are indicated in cartoon format. The aligned sequences are from Pyrococcus furiousus, (NCBI code NP_579342); Methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus (NCBI code NP_276730); P. horikoshii (NCBI code NP_143456); Methanocaldococcus jannaschii (NCBI code NP_247957); Archaeoglobus fulgidus (NCBI code NP_068950); Schizosaccharomyces pombe (NCBI code NP_596472); Mus musculus (NCBI code NP_080584) and Homo sapiens (NCBI code NP_079115). Pfu RPP21 belongs to pfam04032. The figure was generated with ESPRIPT (48).

We determined the solution structure of Pfu RPP21 by application of conventional and state-of-the-art paramagnetic NMR spectroscopy (17). Taking advantage of the metal binding properties of Pfu RPP21, we replaced the diamagnetic Zn2+ with the paramagnetic Co2+, which provided a unique set of restraints otherwise unavailable (18). Furthermore, to provide insights into the interactions between RPP21 and RPP29, chemical shift perturbations (19, 20) were utilized to determine which residues in RPP21 are responsible for interactions with RPP29. These data have allowed us to identify residues within RPP21 that interact with RPP29 in the absence of the RNA, facilitating interpretation of functional defects obtained from alanine scanning mutagenesis (16). This work represents an important step towards a model of the assembly and structure of the RNase P holoenzyme from archaea and eukaryotes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Protein expression and purification

The gene encoding Pfu RPP21 was amplified by PCR from genomic DNA as the template and gene-specific DNA primers (forward: 5′-GCT AAA TAC AAT GAG AAA AAA GAA AAA AAG CGT ATT G; reverse: 5′-C TAG CTC GAG gct gcc gcg cgg cac cag acc acc ATA TTC CAT TTT TTC TTT TCT TCT C; an XhoI restriction site is underlined, the C-terminal Gly-Gly linker and thrombin cleavage site, Leu-Val-Pro-Arg-Gly-Ser, are lower case, and nucleotides altered to improve codon usage for E. coli are in bold) and then sub-cloned into the pET-33b vector (Novagen, Inc.). The recombinant protein was overexpressed in E. coli Rosetta (DE3) cells (Novagen, Inc.) grown at 37°C in minimal M9 media containing 1 g/L 15N ammonium chloride and 2 g/L 13C glucose as the sole nitrogen and carbon sources, respectively, and supplemented with 30 μg/liter kanamycin and 54 μg/liter chloramphenicol. Production of RPP21 was induced by addition of 1 mM isopropyl-D-thiogalactoside (IPTG) and 50 μM zinc chloride when the cells reached OD600 ≈ 0.6, harvested after 4 h by centrifugation. Cells were suspended in denaturing lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 50 mM KCl, 5 mM imidazole, 6 M guanidine-HCl) and lysed by sonication. The protein was purified using a three-step purification protocol. In the first step, affinity chromatography was performed using a 5 mL HiTrap Chelating column (GE Biosciences) charged with 100 mM nickel sulfate and equilibrated with denaturing loading buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 50 mM KCl, 5 mM imidazole, 8 M urea). Second, fractions containing the protein were combined and purified by C4 reversed-phase HPLC (Vydac 214TP1010, 90 mL linear gradient of 30–60% acetonitrile). Then, the C-terminal (His)6 tag was removed by incubation at 37 °C with thrombin (10 units/mg of Pfu RPP21) for 12 h, resulting in a 122-residue protein consisting of 116 natively encoded residues, minus the N-terminal methionine, followed by six plasmid-encoded residues (Gly-Gly-Leu-Val-Pro-Arg). After cleavage of the affinity tag, the protein was purified form the peptide and protease by C4 reversed-phase HPLC chromatography, lyophilized, resuspended in denaturing buffer, and exchanged into NMR buffer (10 mM d11-Tris, pH 6.7 at 25°C, 10 mM KCl, 0.3 mM ZnCl2, 0.02% sodium azide, 10% D2O) using a PD-10 gel filtration column (GE Healthcare). The cobalt-substituted RPP21 sample for measuring paramagnetic effects (below) was obtained by the same purification protocol, except that the pure lyophilized protein was refolded in buffer containing CoCl2 instead of ZnCl2. Protein purity and integrity were assessed by Coomassie Blue staining (Pierce) on SDS-PAGE gels and by electrospray mass spectrometry (Q-TOF II, Micromass, Inc.).

For production of Pfu RPP29, the Pfu RPP29/pET-33b plasmid was transformed into E. coli BL21 (DE3) Rosetta cells (Novagen), recombinant protein production was induced by addition of 1 mM IPTG when the cell density had reached OD600 ≈ 0.6, harvested after 4 hours by centrifugation. Cells were suspended in denaturing lysis buffer (25 mM Tris, pH 7, 7 M urea, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM DTT) and lysed by sonication. The protein was purified from the urea-solubilized lysate using a 5 mL HiTrap SP column equilibrated with lysis buffer. The protein was refolded on the column by washing with 10 column volumes of buffer A (25 mM Tris, pH 7, 25 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT) and was eluted with a 60 mL linear gradient of 0.5 M to 1.5 M NaCl. The purified protein was then dialyzed against Pfu RPP21 NMR buffer (10 mM Tris, pH 6.7, 10 mM KCl, 0.3 mM ZnCl2, 1 mM DTT, 0.02% NaN3). Protein concentration was estimated from the predicted extinction coefficient of 14,770 M−1 cm−1 at 280 nm in denaturing buffer (50 mM phosphate, pH 7.5, 6 M guanidinium hydrochloride) (21).

Limited proteolysis

Purified Pfu P21 (~100 μM in NMR buffer) was subjected to limited proteolysis by adding 5% trypsin (w/w), incubating at 37°C for one hour, and quenched with 0.6 mM PMSF (Sigma). Partially proteolyzed samples were then analyzed by electrospray mass analysis (Q-TOF-II, Micromass).

NMR spectroscopy and resonance assignments

Two dimensional 1H-15N correlated NMR spectra of Pfu RPP21 recorded at 25 °C revealed many broad signals in the random coil chemical shift region of the spectrum (22), suggesting that portions of the protein had aggregated and/or were disordered at low temperature. Nevertheless, NMR data recorded at 50°C showed high quality spectra with well-dispersed resonances. Thus, NMR data were collected at 50°C on 600 MHz and 800 MHz Bruker Avance DMX and DRX spectrometers equipped with triple-resonance triple axis pulsed-field gradient probes. NMR data were processed and analyzed using NMRPipe (23), NMRView (24), CARA (25) and in-house scripts. The approximate concentration for RPP21 NMR samples was 1 mM, while concentrations of Co2+ RPP21 and the RPP21-RPP29 complex were 0.5 mM.

Backbone resonance assignments for RPP21 free and in complex with RPP29 were obtained using standard triple resonance spectra (HNCACB, HNCA, CBCA(CO)NH and HNCO) (26) recorded at 600 MHz. Side-chain resonance assignments were obtained from 15N-edited TOCSY-HSQC (26) (τm 60 ms) at 800 MHz, HBHA(CBCACO)NH, CCONH-TOCSY (τm 12 ms), 3D HCCH-COSY (τm 12 ms) and HCCH-TOCSY (τm 12 ms) at 600 MHz (26) spectra. Distance restraints were obtained from 3D 15N-edited NOESY-HSQC (τm 200 ms) and 13C-edited NOESY-HSQC (τm 200 ms) spectra recorded in samples dissolved in 5% and 100% D2O, respectively. Backbone resonance assignments for Co2+-bound RPP21 were obtained using TROSY-based triple resonance spectra (TROSY-HNCA, TROSY-HNCO, TROSY-HNCACB) (27) recorded at 600 MHz, and a 3D 15N-edited NOESY-TROSY spectrum (28) (τm 150 ms) recorded at 800 MHz.

Structure determination

NOE derived distance restraints from NOESY cross peak intensities were calculated by assigning the median intensity an interproton distance of 2.7 Å, and scaling the remaining intensities assuming a scaling of ~ 1/r6, where r is the interproton distance (24). Restraints for methyl and non-stereo-assigned atoms were adjusted by adding 0.5 Å to the upper bound. Backbone torsion angle restraints were obtained from analysis of the HN, N, Cα and Cβ chemical shifts with TALOS (29). Pseudocontact shifts (PCS) were calculated by comparing the Hα, N, Cα, Cβ and C′ chemical shifts between paramagnetic and diamagnetic spectra (18, 30). Scalar J couplings were obtained from an interleaved TROSY-HSQC spectrum (20).

Structure calculations for free Pfu RPP21 were performed using simulated annealing protocols within the XPLOR-NIH software suite (31), which includes a paramagnetism restraints module (32). An initial set of structures was generated using a small set of unambiguous long-range NOE restraints (~100), in addition to short range NOE restraints and dihedral angle restraints. Paramagnetism-derived PCS restraints were introduced after estimation of the tensor (32). After each cycle, the structures obtained were used to calculate a new PCS tensor and used for iterative assignment of additional NOE crosspeaks. The zinc ion was linked to the four cysteines, modified to remove the Hγ, through upper distance restrains from Cβ (3.3 Å) and Sγ (2.3 Å) and used throughout the calculations. A final set of the 20 lowest energy structures were selected from a set of 100 solutions, and subsequently refined in explicit water (33) using restrained molecular dynamics in XPLOR-NIH (31 2003). Analysis of structures was done using with XPLOR-NIH (31) and PROCHECK-NMR (34). Structures and restraints have been deposited to the Protein Data Bank, under accession code 2K3R.

Identifying the RPP29-binding site of RPP21

The RPP29-interaction site on RPP21 was identified by examining the chemical shift differences between amide resonances of free and RPP29-bound 15N-RPP21 in two dimensional 1H-15N correlated NMR spectra. Weighted average chemical shift perturbations were calculated from:

RESULTS

Pfu RPP21 solution structure

The 15N-edited HSQC spectrum of Pfu RPP21 contains only 90 of the 115 expected backbone amide proton resonances (excluding the 7 proline residues) (Figure 2a). This observation suggested that the N and C termini do not adopt a stable structure, consistent with sequence-based structural predictions (36, 37). Limited trypsin proteolysis experiments analyzed by mass spectrometry revealed two major proteolytic fragments with masses of 8,635 and 11,517 Da, corresponding to the expected masses of residues 37 to 108 (8,632 Da expected) and 13 to 108 (11,520 Da expected), respectively. The absence of significant cleavage of the remaining nine Lys or ten Arg residues suggested the presence of a well-structured central core between residues 13-108, with unstructured N and C termini beyond these bounds.

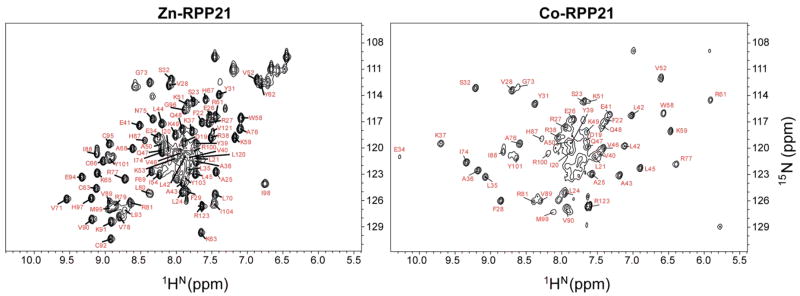

Figure 2.

Two dimensional 1H-15N NMR spectra of Pfu RPP21. Backbone amide assignments as indicated. (a) Zinc-reconstituted RPP21. (b) Cobalt-reconstituted RPP21.

Backbone amide resonance assignments could be obtained for most of the signals observed in 15N-HSQC spectra, corresponding to 83% of the protease-resistant core of the protein (residues 13-108) and to 68% of all residues (Figure 2a). Residues that could not be assigned are 1-17, 56-57, 60, 82-85 and 104-119, corresponding to regions located mainly in the N-terminus, a loop, and the C-terminus. Sidechain assignments were determined for 81% of residues in the core (residues 13-108) and 66% for all the protein.

The effect of the paramagnetic cobalt metal on the 15N-HSQC is illustrated in Figure 2b. Due to the large chemical shift changes induced by the paramagnetic ion, backbone resonances for Co2+-RPP21 had to be assigned de novo. Due to the enhanced relaxation rates of protein spins by the paramagnetic ion (38), the signals from residues in the immediate vicinity of the metal binding site were broadened beyond detection and assignments could only be obtained for 49 residues of Co2+-substituted RPP21. From these assignments, a total of 169 (HN, N, Cα and Cβ) pseudocontact shifts (PCS) (38) could be obtained and were included in the structure calculations.

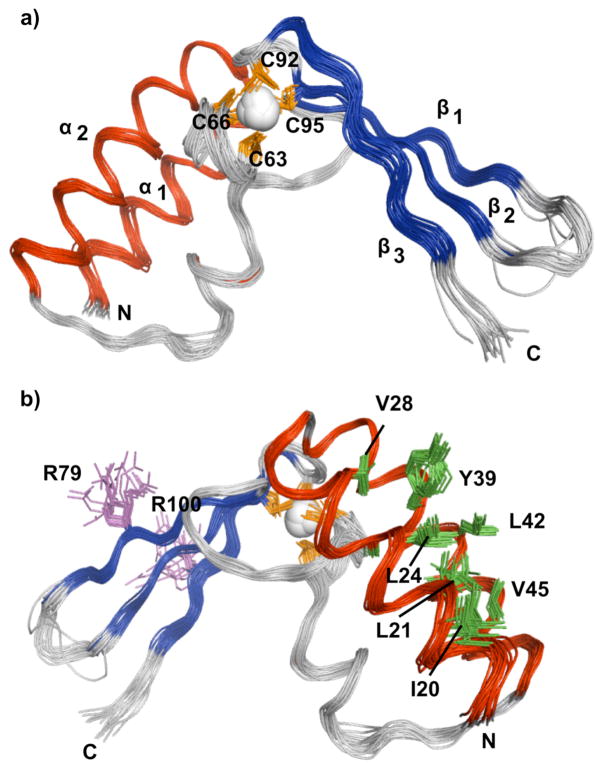

The solution structure of Pfu RPP21 is well defined for the assigned residues (19-82, 88-105), with mean rms deviations (RMSDs) of 0.4 Å and 0.8 Å for backbone and heavy atoms, respectively (Figure 3); inclusion of the PCS restraints decreased the overall RMSDs from 0.6 Å and 0.9 Å for backbone and heavy atoms, respectively. Although the PCS restraints had a modest effect on the precision of the structure, the longer-range information allowed for discrimination of alternative structures early during refinement. Overall, the structural quality is good, with 97% of the ψ and χ angles falling within the favored and additionally allowed regions of the Ramachandran plot (Table 1). The N-terminus of the structured region of the protein (residues 19-52) consists of two α-helices (α1, residues 19-31 and α2, residues 35-50), while the C-terminus of the protein (residues 57-105) adopts a zinc ribbon motif (11, 39) and consists of two-hairpins providing the scaffold for the four invariant cysteine residues responsible for coordinating the zinc ion (Figure 3). The two α-helices dock against the open side of the zinc binding site of the zinc ribbon, protecting the metal from solvent.

Figure 3.

Solution structure of Pfu RPP21. (a) Ensemble of 20 lowest-energy structures superposed on the backbone heavy atoms of residues 19–82,88-105. (b) Rotated view showing the side-chains of some conserved residues.

Table 1.

NMR structure statistics Pfu RPP21.

| NMR constraints | |

| NOE | 1,352 |

| Intraresidue (i − j=0) | 515 |

| Sequential (i− j=1) | 381 |

| Short range (1< i − j <5) | 154 |

| Long range (i − j <5) | 302 |

| Ambiguous | 399 |

| Hydrogen bonds† | 68 |

| Dihedral angles | 158 |

| Pseudocontact shifts (PCS) | 169 |

| Violations | |

| Distance violations > 0.5 Å | 3.4 ± 2.0 |

| Dihedral angle violations > 5° | 0 ± 0 |

| PCS violations | 0 ± 0 |

| Deviation from idealized geometry | |

| Bonds, Å | 0.003 ± 0.0003 |

| Angles, ° | 1.01 ± 0.05 |

| Impropers, ° | 8.1 ± 0.3 |

| Ramachandran statistics§, % | |

| Favored region | 96.6 |

| Disallowed region | 0.0 |

| Precision (RMSD from the mean structure) | |

| Backbone atoms, Å | 0.45 |

| All heavy atoms, Å | 0.81 |

Hydrogen bond restraints were applied as upper bound restraints between amide proton and oxygen atoms, and between amide nitrogen and oxygen atoms.

Ramachandran analysis performed with MolProbity (46)

Amino acid residues that are highly conserved across the RPP21 family decorate both the helical and zinc ribbon domains of the structure (Figure 1). The core is well packed with highly conserved hydrophobic residues (not shown), with the three invariant hydrophobic residues (Leu21, Tyr39 and Ala43) forming part of the primary hydrophobic pocket keeping the helices together (Figure 3b). Of the three invariant arginine residues (Arg17, Arg79, Arg100), the side chains of Arg79 and Arg100 are solvent exposed (Figure 3b), while Arg17 is located in the disordered N-terminal region that precedes helix α1. The pairings of several basic and acidic residues on the surface of the two helices (Glu16-Arg17, Glu26-Arg27 and Glu34-Arg38-Glu41) reveal a number of surface salt bridges that likely contribute to protein stability.

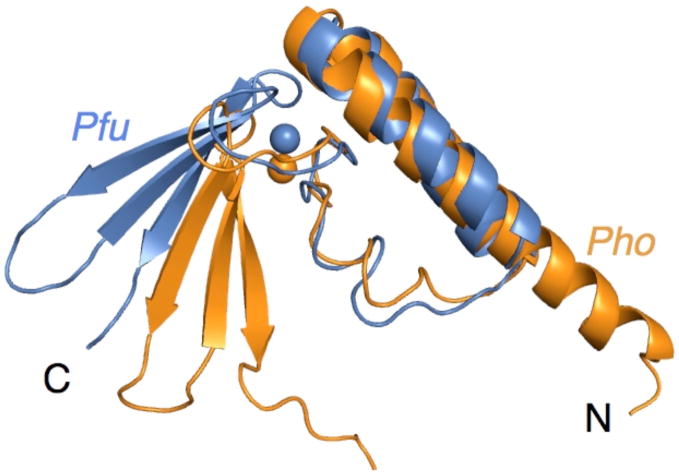

A crystal structure has been reported for P. horikoshii (Pho) RPP21 (16), which exhibits 69% sequence identity with Pfu RPP21. Superposition of the core structural elements (Pfu residues 17-103; Pho residues 18-104) of a representative member from the NMR ensemble and the x-ray structure yields an RMSD of 3.3 Å. However, separate superposition of the α-helices (residues 18-49) and the zinc binding motif (residues 67-82 and 88-101) yields RMSDs of 1.1 Å and 1.3 Å, respectively. Most of the structural difference between the Pho and Pfu structures lies in the linker (residue 51-62) that connects the N- and C-terminal regions, changing the relative orientation between the two α-helices and the zinc ribbon; although there was no evidence for flexibility in the NMR data, it seems likely that the precise geometry between the domains could vary. In addition, the first 13 residues of Pfu RPP21 were not observed to form a stable secondary structure in solution (at 55°C), while for the crystal structure of P. horikoshii RPP21 (16) the N-terminal alpha helix was extended into this region of the protein (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Superposition of Pfu and Pho RPP21. Superposition of the core structural elements of a representative member from the NMR ensemble and the x-ray structure.

RPP21 binds to RPP29

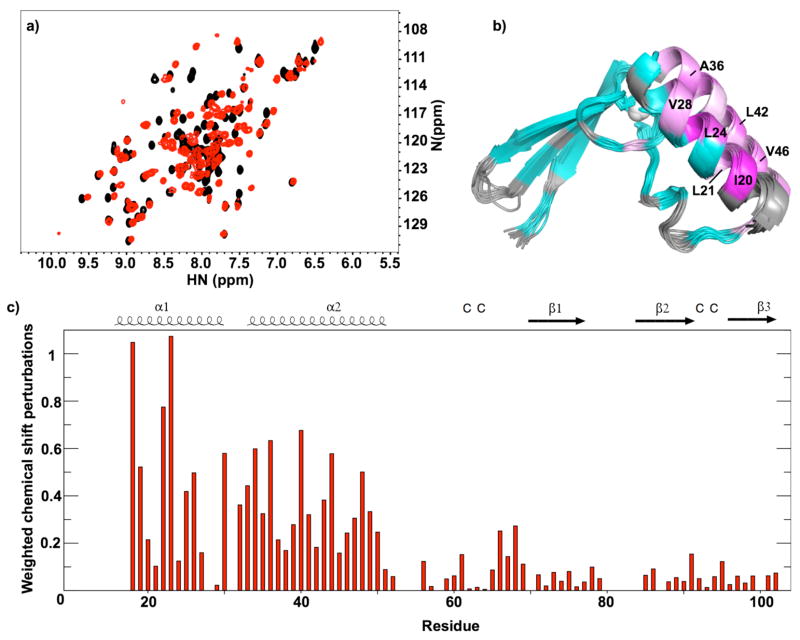

Unlabeled RPP29 was titrated into solutions containing 15N-labeled RPP21 to identify significant regions of interaction. NMR spectra of RPP21 partially saturated with RPP29 showed two sets of signals, indicating tight binding with dissociation being slow on the chemical shift timescale. Comparison of the 15N HSQC spectra of Pfu RPP21 in the absence and presence of Pfu RPP29 reveals many chemical shift perturbations confirming the interactions suggested previously by yeast two-hybrid experiments (Figure 5) (6, 7). The addition of RPP29 in stoichiometric excess did not result in further changes in the HSQC sectrum of RPP21, consistent with high-affinity 1:1 stoichiometry. The improvement in signal-to-noise and the reduction of overlap in the 15N HSQC spectra of RPP21 when bound to RPP29 suggest that the protein is better folded when bound to its binary partner. Although some backbone resonance assignments could be inferred by comparing the 15N HSQC spectra of the complex to the free RPP21, large shift perturbations required re-assigning the backbone resonances of RPP21 when bound to RPP29. We obtained resonance assignments for all but residues 1-18, 56-57, 60, 78-85 and 104-119. The largest backbone amide chemical shift perturbations induced by RPP29 are localized to the α-helices at the N-terminus of RPP21 (Figure 5b-c). A majority of the residues experiencing the largest amide shift perturbations are hydrophobic, particularly Ile20, Leu21, Leu24, Ala25, Val28, Leu42 and Val46. In addition to hydrophobic residues, several charged (Arg27 and Arg38) and polar (Ser32) residues exhibited large shift perturbations. These chemical shift perturbations identify the RPP21-RPP29 protein-protein interface (19).

Figure 5.

Binding of Pfu RPP21 to Pfu RPP29 as detected by NMR. a) Overlay of 15N HSQC spectra of Pfu RPP21 free (black) and Pfu RPP21 bound to Pfu RPP29 (red), illustrating the site-specific chemical shift perturbations that reveal the region of protein-protein interactions. b) Binding-induced chemical shift perturbations mapped onto the ribbon diagram of RPP21 structure, using a linear ramp from cyan (less than the mean perturbation) to magenta (normalized maximal perturbation). Residues for which the effect of RPP29 binding could not be determined are shown in light gray. c) Plot of weighted average chemical shift perturbations induced by protein-protein contacts.

DISCUSSION

While the exact functional role of each of the protein subunits of archaeal and eukaryotic RNase P remains to be determined, evidence suggests that at least some of the RNase P proteins function in pairs (5, 40), and contact either the RPR subunit (41, 42) or ptRNA substrate (9). An important step towards revealing the roles of the protein pairs is to understand their structure in solution and how they interact with the other components. The solution structure of Pfu RPP21 contains a structured central core (residues 15-105), and unstructured regions at both N- and C-termini. Both of these tails are highly populated by conserved basic residues that could help stabilize interactions with either the catalytic P RNA subunit or the substrate ptRNA through favorable electrostatic interactions.

The overall RPP21 protein fold is unique among family members (MMDB ID: 35869) (43). The zinc ribbon domain that comprises residues ~60-104 however, is a common domain among nucleic acid binding proteins (44). As previously noted, this domain exhibits a high degree of similarity to archaeal and eukaryotic polymerase subunits exemplified by Rpb9 (16). Superposition of the zinc ribbon fold of RPP21 with that of Rpb9 from yeast RNA polymerase II positions the domain near the nucleic acid binding funnel (45), where its conserved arginine and lysine residues could make analogous contacts with nucleic acid substrates.

Chemical shift perturbations induced by RPP29 clearly indicate (Figure 5) that Pfu RPP21 forms a tight complex with Pfu RPP29 in the absence of the RPR. These perturbations indicate that the interaction is localized to the two α-helices of RPP21, which exhibit a number of exposed hydrophobic residues (Figures 3 and 5). Although increased signal dispersion was observed in the complex, no new resonances were observed for RPP21 upon binding RPP29, suggesting that no significant coupled folding of RPP21 occurs upon binding, and that the protein-protein interaction involves the structured core RPP21. Such an interaction would leave the highly basic N- and C-terminal tails free to interact with either the RPR or the ptRNA.

Alanine scanning mutagenesis experiments directed at conserved residues in Pho RPP21 identified residues important for functional reconstitution (16). Those studies, although not quantitative, found that mutation to Ala of Arg17, Tyr39, Arg65, Arg81 and Arg100 (Pfu numbering) significantly impaired activity in the reconstituted enzyme, with the largest defects being associated with the Arg65-Ala and Arg100-Ala mutants. Given the location of Arg17 and Tyr39 in the NMR-identified interface with RPP29, we conclude that mutation of those residues might have impaired formation of the appropriate protein-protein contacts. On the other hand, Arg65 and Arg100 are located on the zinc ribbon motif, away from the RPP29 binding site. Yeast two-hybrid (6–8) and biophysical experiments (unpublished results) indicate little or no interaction between the RPP21-RPP29 and POP5-RPP30 protein pairs. Consequently, functional defects due to these RPP21 mutations implicate them and their associated molecular surfaces in binding either the RPR or ptRNA substrate.

The present work has identified the molecular surface of RPP21 involved in binding RPP29, thereby informing the design of site-directed mutations aimed at probing interactions with the RNA subunit. Further studies will ascertain the details of how Pfu RPP21 interacts with RPP29 and how this complex interacts with other components of RNase P. Such studies should help reveal the function of the RPP21-RPP29 complex within the holoenzyme and allow further progress towards understanding assembly and function of this composite ribonucleoprotein enzyme.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank C. Yuan (CCIC) for assistance with NMR data collection, C. P. Jones (OSU) for help with sample preparation, and R. C. Wilson and members of the V. Gopalan lab (Biochemistry) for reagents, encouragement and helpful discussions.

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (GM67807) to MPF and Venkat Gopalan (OSU).

Abbreviations

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- TROSY

transverse relaxation optimized spectroscopy

- HSQC

heteronuclear single quantum correlation spectroscopy

- NOE

nuclear Overhauser effect

- PCS

pseudochemical shifts

- Pfu

Pyrococcus furiosus

- RPP

RNase P protein

- RPR

RNase P RNA

- ptRNA

precursor tRNA

References

- 1.Altman S, Baer MF, Bartkiewicz M, Gold H, Guerrier-Takada C, Kirsebom LA, Lumelsky N, Peck K. Catalysis by the RNA subunit of RNase P--a minireview. Gene. 1989;82:63–64. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90030-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gopalan V, Altman S. In: Ribonuclease P: Structure and Catalysis, in The RNA World. Gesteland R, Cech T, Atkins J, editors. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; New York: 2006. only online at http://rna.cshl.edu) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Evans D, Marquez SM, Pace NR. RNase P: interface of the RNA and protein worlds. Trends Biochem Sci. 2006;31:333–341. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hall TA, Brown JW. Archaeal RNase P has multiple protein subunits homologous to eukaryotic nuclear RNase P proteins. RNA. 2002;8:296–306. doi: 10.1017/s1355838202028492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsai HY, Pulukkunat DK, Woznick WK, Gopalan V. Functional reconstitution and characterization of Pyrococcus furiosus RNase P. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:16147–16152. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608000103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jiang T, Altman S. Protein-protein interactions with subunits of human nuclear RNase P. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:920–925. doi: 10.1073/pnas.021561498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kifusa M, Fukuhara H, Hayashi T, Kimura M. Protein-protein interactions in the subunits of ribonuclease P in the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus horikoshii OT3. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2005;69:1209–1212. doi: 10.1271/bbb.69.1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hall TA, Brown JW. Interactions between RNase P protein subunits in archaea. Archaea. 2004;1:247–254. doi: 10.1155/2004/743956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jarrous N, Reiner R, Wesolowski D, Mann H, Guerrier-Takada C, Altman S. Function and subnuclear distribution of Rpp21, a protein subunit of the human ribonucleoprotein ribonuclease P. RNA. 2001;7:1153–1164. doi: 10.1017/s1355838201010469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mann H, Ben-Asouli Y, Schein A, Moussa S, Jarrous N. Eukaryotic RNase P: role of RNA and protein subunits of a primordial catalytic ribonucleoprotein in RNA-based catalysis. Mol Cell. 2003;12:925–935. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00357-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qian X, Jeon C, Yoon H, Agarwal K, Weiss MA. Structure of a new nucleic-acid-binding motif in eukaryotic transcriptional elongation factor TFIIS. Nature. 1993;365:277–279. doi: 10.1038/365277a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boomershine WP, McElroy CA, Tsai HY, Wilson RC, Gopalan V, Foster MP. Structure of Mth11/Mth Rpp29, an essential protein subunit of archaeal and eukaryotic RNase P. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:15398–15403. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2535887100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilson RC, Bohlen CJ, Foster MP, Bell CE. Structure of Pfu Pop5, an archaeal RNase P protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:873–878. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508004103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kawano S, Nakashima T, Kakuta Y, Tanaka I, Kimura M. Crystal structure of protein Ph1481p in complex with protein Ph1877p of archaeal RNase P from Pyrococcus horikoshii OT3: implication of dimer formation of the holoenzyme. J Mol Biol. 2006;357:583–591. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.12.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takagi H, Watanabe M, Kakuta Y, Kamachi R, Numata T, Tanaka I, Kimura M. Crystal structure of the ribonuclease P protein Ph1877p from hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus horikoshii OT3. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;319:787–794. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.05.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kakuta Y, Ishimatsu I, Numata T, Kimura K, Yao M, Tanaka I, Kimura M. Crystal structure of a ribonuclease P protein Ph1601p from Pyrococcus horikoshii OT3: an archaeal homologue of human nuclear ribonuclease P protein Rpp21. Biochemistry. 2005;44:12086–12093. doi: 10.1021/bi050738z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Banci L, Piccioli M, Arnesano F. NMR structures of paramagnetic metalloproteins. Quarterly Reviews of Biophysics. 2005;38:167–219. doi: 10.1017/S0033583506004161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jensen MRb, Hansen DF, Ayna U, Dagil R, Hass MAS, Christensen HEM, Led JJ. On the use of pseudocontact shifts in the structure determination of metalloproteins. Magn Reson Chem. 2006;44:294–301. doi: 10.1002/mrc.1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Foster MP, Wuttke DS, Clemens KR, Jahnke W, Radhakrishnan I, Tennant L, Reymond M, Chung J, Wright PE. Chemical shift as a probe of molecular interfaces: NMR studies of DNA binding by the three amino-terminal zinc finger domains from transcription factor IIIA. J Biomol NMR. 1998;12:51–71. doi: 10.1023/a:1008290631575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Foster MP, McElroy CA, Amero CD. Solution NMR of large molecules and assemblies. Biochemistry. 2007;46:331–340. doi: 10.1021/bi0621314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gasteiger E, Hoogland C, Gattiker A, Duvaud S, Wilkins MR, Appel R. In: The Proteomics Protocols Handbook. Walker JM, editor. Humana Press; 2005. pp. 571–607. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boomershine WP., PhD . STRUCTURE AND INTERACTIONS OF ARCHAEAL RNase P PROTEINS Mth Rpp29 AND Pfu Rpp21. Ohio State Biochemistry Program, The Ohio State University; Columbus, OH: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Delaglio F, Grzesiek S, Vuister GW, Zhu G, Pfeifer J, Bax A. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson BA. Using NMRView to visualize and analyze the NMR spectra of macromolecules. Methods Mol Biol. 2004;278:313–352. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-809-9:313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keller R. The Computer Aided Resonance Assignment Tutorial. CANTINA Verlag Verlag; 2004. 3-85600-85112-85603. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cavanagh FPSR. Protein NMR Spectroscopy: Principles and Practice. 2. Academic Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Salzmann M, Pervushin K, Wider G, Senn H, W¸thrich K. TROSY in triple-resonance experiments: new perspectives for sequential NMR assignment of large proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:13585–13590. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhu G, Kong X, Sze K. Gradient and sensitivity enhancement of 2D TROSY with water flip-back, 3D NOESY-TROSY and TOCSY-TROSY experiments. J Biomol NMR. 1999;13:77–81. doi: 10.1023/A:1008398227519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cornilescu G, Delaglio F, Bax A. Protein backbone angle restraints from searching a database for chemical shift and sequence homology. J Biomol NMR. 1999;13:289–302. doi: 10.1023/a:1008392405740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bertini I, Savellini GG, Romagnoli A, Turano P, Cremonini MA, Luchinat C, Gray HB, Banci L. Pseudocontact shifts as constraints for energy minimization and molecular dynamics calculations on solution structures of paramagnetic metalloproteins. Proteins: Structure, Function, and Genetics. 1997;29:68–76. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0134(199709)29:1<68::aid-prot5>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schwieters CD, Kuszewski JJ, Tjandra N, Clore GM. The Xplor-NIH NMR molecular structure determination package. J Magn Reson. 2003;160:65–73. doi: 10.1016/s1090-7807(02)00014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bertini I, Cavallaro G, Giachetti A, Luchinat C, Parigi G, Banci L. Paramagnetism-Based Restraints for Xplor-NIH. J Biomol NMR. 2004;28:249–261. doi: 10.1023/B:JNMR.0000013703.30623.f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spronk CAEM, Linge JP, Hilbers CW, Vuister GW. Improving the quality of protein structures derived by NMR spectroscopy. J Biomol NMR. 2002;22:281–289. doi: 10.1023/a:1014971029663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laskowski RA, Rullmannn JA, MacArthur MW, Kaptein R, Thornton JM. AQUA and PROCHECK-NMR: programs for checking the quality of protein structures solved by NMR. J Biomol NMR. 1996;8:477–486. doi: 10.1007/BF00228148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rooney LM, Sachchidanand, Werner JM. Characterizing domain interfaces by NMR. Methods Mol Biol. 2004;278:123–138. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-809-9:123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Su CT, Chen CY, Hsu CM. iPDA: integrated protein disorder analyzer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W465–472. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ishida T, Kinoshita K. PrDOS: prediction of disordered protein regions from amino acid sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W460–464. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bertin I, Luchinat C, Parigi G. Magnetic susceptibility in paramagnetic NMR. Progress in Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. 2002;40:249–273. doi: 10.1016/j.pnmrs.2019.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Qian X, Gozani SN, Yoon H, Jeon CJ, Agarwal K, Weiss MA. Novel zinc finger motif in the basal transcriptional machinery: three-dimensional NMR studies of the nucleic acid binding domain of transcriptional elongation factor TFIIS. Biochemistry. 1993;32:9944–9959. doi: 10.1021/bi00089a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pulukkunat DK, Gopalan V. Studies on Methanocaldococcus jannaschii RNase P reveal insights into the roles of RNA and protein cofactors in RNase P catalysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:4172–4180. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Houser-Scott F, Xiao S, Millikin CE, Zengel JM, Lindahl L, Engelke DR. Interactions among the protein and RNA subunits of Saccharomyces cerevisiae nuclear RNase P. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:2684–2689. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052586299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jiang T, Guerrier-Takada C, Altman S. Protein-RNA interactions in the subunits of human nuclear RNase P. Rna. 2001;7:937–941. doi: 10.1017/s1355838201010299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang Y, Addess KJ, Chen J, Geer LY, He J, He S, Lu S, Madej T, Marchler-Bauer A, Thiessen PA, Zhang N, Bryant SH. MMDB: annotating protein sequences with Entrez’s 3D-structure database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D298–300. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Krishna SS, Majumdar I, Grishin NV. Structural classification of zinc fingers: survey and summary. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:532–550. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cramer P, Bushnell DA, Kornberg RD. Structural basis of transcription: RNA polymerase II at 2.8 angstrom resolution. Science. 2001;292:1863–1876. doi: 10.1126/science.1059493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Davis IW, Leaver-Fay A, Chen VB, Block JN, Kapral GJ, Wang X, Murray LW, Arendall WB, 3rd, Snoeyink J, Richardson JS, Richardson DC. MolProbity: all-atom contacts and structure validation for proteins and nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W375–383. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li KB. ClustalW-MPI: ClustalW analysis using distributed and parallel computing. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1585–1586. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gouet P, Robert X, Courcelle E. ESPript/ENDscript: Extracting and rendering sequence and 3D information from atomic structures of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3320–3323. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]