Abstract

The relationships among adult attachment styles, interpersonal problems, and categories of suicide-related behaviors (i.e., self-harm, suicide attempts, and their co-occurrence) were examined in a predominantly psychiatric sample (N= 406). Both anxious and avoidant attachment styles were associated with interpersonal problems. In turn, specific interpersonal problems differentially mediated the relations between attachment style and type of suicide-related behaviors. These findings suggest the importance of distinguishing between these groups of behaviors in terms of etiological pathways, maintenance processes, and treatment interventions.

In the general population, the prevalence of suicide-related behaviors has been estimated at 4.6% (Kessler, Borges, & Walters, 1999; Nock & Kessler, 2006). The prevalence of these behaviors among psychiatric patients is much higher, with psychiatric diagnosis increasing the odds of suicide attempt from 1 to 9 times (e.g., Linehan, Rizvi, & Welch, 2000; Nock & Kessler, 2006). Although previous research indicates that attachment and interpersonal problems can elevate the risk for suicide-related behaviors, no studies have examined the mediational mechanisms underlying these links. Also, studies often fail to distinguish between suicide-related behaviors in terms of intent, as recommended by Silverman, Berman, Sanddal, O'Carroll, and Joiner (2007a; 2007b). Evidence of self-injurious behavior without the intent to die is classified as self-harm (SH), self-injurious behavior with the intent to die is classified as suicide attempt (SA). The lack of demarcation has limited our understanding of the specific pathways to these behaviors. In the present study we tested whether interpersonal problems mediated in a differential way the relation between attachment styles and SH and SA in a predominantly psychiatric sample.

Attachment Styles and Suicide-Related Behaviors

Attachment style is a general risk factor for psychopathology. Evidence suggests that those with secure attachment styles in childhood have fewer symptoms of psycho-pathology and higher psychosocial functioning throughout the life span when compared to individuals with an insecure attachment style (e.g., Cassidy & Mohr, 2001; Sroufe, 2005; Ward, Lee, & Polan, 2006). Traditionally, three primary attachment patterns have been described in children (Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, 1978) and adults (Hazan & Shaver, 1987): secure, avoidant, and anxious-ambivalent attachment. Securely attached individuals feel close to others and are able to rely on them. Avoidantly attached individuals, also called dismissive, experienced emotionally distant or unresponsive caregiving in childhood; they are uncomfortable with closeness and over-value independence. Anxious-ambivalent individuals, also called preoccupied, had unpredictable caregivers in childhood; they strongly desire close relationships, fear abandonment, and often find that others will not get as close as they desire. These different attachment styles have been used to describe interpersonal relationships across the life span, and they are associated with different forms of psychopathology (see Blatt & Levy, 2003; Levy & Blatt, 1999 for reviews). An anxious style is related to borderline, histrionic, and dependent personality disorder features weh. An avoidant style is associated with symptoms of narcissistic, avoidant, antisocial, and schizoid personality disorders.

An insecure attachment style is also related to suicidality. In adolescent psychiatric samples, an insecure attachment style is associated with suicidal ideation and other suicidal behaviors (Adam, Sheldon-Keller, & West, 1996; de Jong, 1992; Violato & Arato, 2004; Wright, Briggs, & Behringer, 2005). Wright et al. (2005) found that adolescents at high risk for suicide were more likely to exhibit a preoccupied attachment style than either an avoidant or secure style when compared to those at low risk for suicide and controls. In a prospective design with adults, van der Kolk, Perry, and Herman (1991) found that patients with a history of separation or neglect from a primary caregiver (“disrupted attachment”) were more likely to engage in SH and SA behaviors 4 years after an initial assessment than those with a more stable childhood attachment. We view attachment style, internalized from earlier experiences with caregivers, as a distal risk factor for psychopathology (see Vaughn, 2005), thus we chose to focus on current interpersonal problems as mediators between attachment style and self-harm and suicide attempts.

Interpersonal Problems as a Mediator Between Attachment Styles and Suicide-Related Behaviors

Interpersonal problems have been demonstrated to be a critical link to suicide-related behaviors. For example, Linehan, Chiles, Egan, Devine, and Laffaw (1986) found that inpatients admitted for suicide-related behaviors were more likely to report presenting problems of an interpersonal nature than those patients admitted for suicidal ideation or for a nonsuicidal problem. Interpersonal motives are also frequently endorsed as reasons for engaging in suicide-related behaviors (Brown, Comtois, & Linehan, 2002). Brown et al. (2002) found that 61% of individuals who had most recently engaged in SH and 45% of those who had most recently had a SA reported items related to “interpersonal influence” as reasons for engaging in that particular behavior. Lastly, researchers have found that real or perceived interpersonal events often precipitate suicide-related behavior in patients with borderline personality disorder (Blatt, Auerbach, & Levy, 1997; Fonagy et al., 1996; Gunderson, 1996; Levy & Blatt, 1999; Yeomans & Levy, 2002).

Interpersonal problems can discriminate between those who engage in suicide-related behaviors from those who do not. Specifically, interpersonal sensitivity has been found to discriminate between people who engage in SH versus those who do not engage in such behavior (Klonsky, Oltmanns, & Turkheimer, 2003). Klonsky et al. found that army recruits who reported SH were more likely to be nominated by their peers as “worrying about social rejection” and “being nervous and mistrustful of others” than those who denied engaging in those behaviors. Additionally, women with borderline personality disorder who presented for treatment with a primary problem of engaging in suicide-related behaviors were more likely to report that interpersonal events would be “high-risk” situations for engaging in this behavior when compared to those with a primary problem of drug dependence (Welch & Linehan, 2002). Lastly, deficits in interpersonal problem solving have been shown to discriminate between suicidal and nonsuicidal individuals (Howat & Davidson, 2002; Kehrer & Linehan, 1996).

Attachment theory posits that patterns of behaving with others are transferred from one relationship to the next, which explains the stability of attachment into adulthood (e.g., Brumbaugh & Fraley, 2006; Fraley, 2002). Few studies, however, have examined the relationship between attachment styles and specific interpersonal problems. Among undergraduates, the traditional attachment dimensions of anxiety (secure to fearful) and avoidance (preoccupied to dismissive) are well represented in interpersonal circumplex space. The interpersonal circumplex model provides a taxonomy of interpersonal behavior in a circular matrix, with one axis representing the continuum of domineering to nonassertive interpersonal behavior and a perpendicular axis representing cold to affiliative behavior (see Gurtman, 1994, for a review of this model). Studies have demonstrated that adult attachment security is associated with a warm, dominant interpersonal style (Bartholomew & Horowitz, 1991; Gallo, Smith, & Ruiz, 2003). In both self-report and peer-report ratings, preoccupied attachment was related to problems in the warm-dominant quadrant, fearful attachment was related to problems in the cold-passive quadrant, and dismissive attachment was related to problems with lack of warmth in social interactions (Bartholomew & Horowitz, 1991). Gallo and colleagues' found that the anxiety dimension shared more variance with interpersonal problems than the avoidance dimension, including personality traits, recollections of parents, and current interpersonal functioning. Given that difficulty in interpersonal relationships is a hallmark feature of personality disorder, we chose to investigate the role of interpersonal problems that have been associated with personality pathology— interpersonal sensitivity, ambivalence, aggression, need for social approval, and lack of sociability—as mechanisms for explaining suicide-related behaviors (Pilkonis, Kim, Proietti, & Barkham, 1996).

Differential Prediction of Self-Injury, Suicide Attempts, and Their Combination

Most research on suicide-related behavior either examines SH or SA behaviors in isolation or aggregates them into an overall category of “suicidal,” “parasuicidal,” or “self-harm” behaviors. Yet these acts are conceptualized as having different intent. Those who engage in SA intend to die as a consequence of their behavior, whereas those who engage in SH do not. Further measurement complication stems from the fact that some individuals who engage in suicide-related behavior often engage in both SH and SA. Therefore, failing to separate these behaviors may have muddied the water in terms of identifying specific etiological pathways, developmental trajectories, and treatment interventions specific to these groups of behaviors (see Linehan, 1997; Nock & Kessler, 2006; Silverman et al, 2007a, 2007b).

Little research has investigated the possible specific mechanisms underlying these groups of behaviors, with the focus instead on identifying risk factors for engaging in suicide-related behavior. For example, Nock and Kessler (2006) examined risk factors that were differentially associated with SA versus SH. Findings were consistent with previous work about risk for SA. They found that male gender, multiple psychiatric diagnoses (especially those involving depressive, aggressive, and impulsive features), and repeated sexual and/or physical abuse were specific risk factors for SA when compared to SH. They also found that living in the southern and western regions of the United States and fewer years of education were more characteristic of SA. The authors identified female gender as a specific risk factor for SH. Interpersonal problems have also been found to have a differential association with type of suicide-related behavior. Brown et al. (2002) found that the desire “to make others better off” discriminated between those whose index behavior was SA from SH. Additionally, feelings of being a burden on others and social isolation have been identified as risk factors for completed suicide (Stellrecht et al., 2006; Van Orden, Merrill, & Joiner, 2005).

To our knowledge, the current study is the first to examine the differential associations of SH, SA, and their combination from attachment and interpersonal problems, above and beyond the contribution of known demographic risk factors, gender, age, and ethnicity. Although this study is largely exploratory in nature, we predicted that interpersonal problems leading to social isolation would predict SA, while those processes characterized by conflicted engagement (e.g., interpersonal sensitivity) would predict SH.

Method

Procedure

Participants (N= 406) were recruited from psychiatric inpatient, psychiatric outpatient, medical, and university settings (see Table 1 for descriptive data). The mean age of the sample was 37.2 years (SD = 10.5) and 270 participants (66.5%) were female. Three hundred thirty-nine participants (83.5%) identified themselves as Caucasian, 59 (14.5%) as African American, 6 (1.5%) as Asian American, and 2 as Hispanic (0.5%).

TABLE 1. Demographic Characteristics.

| Total (N= 406) | SH+SA (N=61) | SH (N= 43) | SA (N=48) | NONE (N=254) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||||

| % Female | 49.8 | 63.9b | 65.1ab | 47.9ab | 44.1.a |

| % Non-Hispanic Caucasian | 83.5 | 83.6a | 88.4a | 79.2a | 83.5a |

| Mean age (SD) | 37.16 (10.50) | 33.84 (10.17)a | 32.10 (8.92)a | 37.60 (10.11)ab | 38.7 (10.50)b |

| % Married | 32.0 | 36.1a | 58.1a | 29.2a | 27.2a |

| % Graduated from college | 29.8 | 26.2ab | 37.2ab | 10.4a | 33.1b |

| Current Axis I diagnoses | |||||

| % Mood disorder | 68.2 | 98.4b | 76.7b | 83.3b | 57.6a |

| % Anxiety disorder | 41.9 | 59.0b | 65.1b | 39.6ab | 34.3a |

| % Alcohol/drug disorder | 48.3 | 29.5bc | 18.6ac | 39.6b | 13.0a |

| % Eating disorder | 4.9 | 6.6a | 11.6a | 8.3a | 2.8a |

| % Somatic disorder | 5.4 | 14.8b | 4.7ab | 4.2ab | 3.5a |

| % Other disorder | 7.6 | 13.1a | 14.0a | 6.3a | 5.5a |

| Mean (SD) number of current Axis I diagnoses | 1.74 (1.24) | 2.67 (1.15)c | 2.37 (1.27)b | 2.08 (1.22)b | 1.34 (1.07)a |

| Lifetime Axis II diagnoses | |||||

| % Cluster A disorder | .7 | .0a | .0a | .0a | 1.2a |

| % Cluster B disorder | 15.0 | 29.5b | 23.3ab | 20.8ab | 9.1a |

| % Cluster C disorder | 18.5 | 23.0ab | 30.2b | 29.2b | 13.4a |

| Mean (SD) number of current Axis II diagnoses | .79 (.75) | 1.09 (.60)b | .95 (.53)ab | .90 (.59)ab | .67 (.82)a |

| Mean (SD) of Attachment Anxiety | .02 (.91) | .81 (.73)c | .26 (.88)b | .25 (.93)b | −.26 (.82)a |

| Mean (SD) of Attachment Avoidance | −.01 (.88) | −.30 (.83)a | −.08 (.91)ab | −.05 (.78)ab | .08 (.90)b |

| Mean (SD) of Sensitivity | 1.74 (.84) | 2.26 (.69)b | 2.33 (.77) b | 1.92 (.80)b | 1.49 (.78)a |

| Mean (SD) of Ambivalence | .93 (.71) | 1.04 (.62)b | 1.26 (.81)ab | 1.08 (.79)ab | .82 (.68)a |

| Mean (SD) of Aggression | 1.07 (.88) | 1.37 (.93)b | 1.21 (.90) b | 1.24 (1.06)b | .94 (.80)a |

| Mean (SD) of Need for Social Approval | 1.95 (.99) | 2.43 (.96)b | 2.48 (.89)b | 2.13 (.93)a | 1.72 (.94)a |

| Mean (SD) of Lack of Sociability | 1.60 (1.03) | 2.02 (.93)b | 2.23 (1.04)b | 1.93 (.94)b | 1.33 (.97)a |

Note. Tukey's HSD was conducted to determine mean differences between groups. Groups not sharing the same subscript are different at p < .05 or less.

Eighty-four percent of the participants (n = 342) were solicited from inpatient and outpatient treatment programs at Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic. Patients with psychotic disorders, organic mental disorders, and mental retardation were excluded as were patients with major medical illnesses that influence the nervous system and might be associated with organic personality changes (e.g., Parkinson's disease, cerebrovascular disease, and seizure disorders). Five percent of participants (n = 22) were diabetic patients not receiving any psychiatric treatment, and 10.3% in = 42) were persons from the community not receiving either medical or psychiatric treatment. All study procedures were approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board. All participants agreed to participate voluntarily and provided written informed consent after receiving a complete explanation of the study.

Before inclusion in the study, nonpsychiatric participants were screened using the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems, the Temperament and Character Inventory self-directedness subscale, and the Iowa Personality Disorder Screen. Based on these screening measures, 50% of the nonpsychiatric participants were judged to have significant amounts of personality pathology and 50% were judged to have little personality pathology.

Measures

Consensus Ratings of Attachment Styles

A complete description of the consensus rating process used in our research program has been provided in previous reports (Pilkonis et al., 1995). A briefer summary of the procedure is included here. At intake, each participant was interviewed for a minimum of three 2-hour sessions by a single interviewer. Assessments included structured diagnostic interviews for Axis I (SCID-I; First, Gibbon, Spitzer, & Williams, 1995) and Axis II disorders (SCID-II; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1997, and SIDP-IV, Pfohl, Blum, & Zimmerman, 1997), as well as a semistructured interview of social and developmental history (the Interpersonal Relations Assessment; Heape, Pilkonis, Lambert, & Proietti, 1989). Interviewers (n = 21) consisted of individuals with a minimum education level of a master's degree in psychology or social work. Interviewers were trained to administer assessments by the principal investigator (PAP) and senior research staff.

After the evaluations, the primary interviewer presented the case to a research team (at least three individuals were present) at a 2- to 3-hour diagnostic conference. All available data (historical and concurrent) were reviewed and discussed at the conference. Judges were given access to all interview data that had been collected, including current and lifetime Axis I information, symptomatic status, social and developmental history, life events, and personality features. Judges were blind to all data from self-report questionnaires.

In an effort to uncover facets of anxious and avoidant attachment, Pilkonis (1988) extracted from the clinical literature 88 descriptors of excessively dependent and excessively autonomous individuals (see also Schmidt, Nachtigall, Wuethrich-Martone, & Strauss, 2002; Strauss et al., 2006). Cluster analyses based on clinicians' ratings of these descriptors yielded a number of specific attachment prototypes. Facets of excessive autonomy or avoidant attachment were labeled (a) defensive separation (e.g., “Maintains strong personal boundaries, great stress is placed on defining her/himself as separate and different from others”), (b) emotional detachment (e.g., “Is somewhat oblivious to the effects of her/his actions on other people; is rather insensitive to other people's needs and wishes”), and (c) rigid control (e.g., “Keeps a stiff upper lip in the face of stress and problems; prefers not to discuss problems and feelings with others”).

For excessive preoccupation or anxious attachment, three subtypes emerged: (a) excessive dependency (e.g., “Tends to give up control to others, underestimates her/his own abilities and resources for coping”), (b) conflicted ambivalence (e.g., “Experiences anger (and even rage) over real (and perceived) deprivation”), and (c) compulsive care-giving (e.g., “Has close relationships, but always takes the role of giving care and not that of receiving it”). Also, a prototype of secure attachment (e.g., “Is able to both depend on others when appropriate and to have others depend on her/him when needed”) was included when initial work made it clear that low ratings on the insecure variants did not necessarily capture secure relatedness (Strauss, Lobo-Drost, & Pilkonis, 1999). Based on all information available to them, judges voted on the presence of discrete criteria (n = 88) for each attachment prototype. Next, judges provided an overall rating of how well the patient fit the overall pattern, ranging from 1 (Not at all to very little) to 5 (To a marked extent) for each of the seven global prototype ratings.

We conducted an exploratory factor analysis with maximum likelihood estimation and varimax rotation of attachment styles using the seven prototype global ratings. An examination of the scree plot and eigenvalues suggested that a two-factor solution was most appropriate. Our factor analysis captured the two dimensions traditionally assessed by attachment instruments—anxiety and avoidance (e.g., Brennan, Clark, & Shaver, 1998). The first factor, labeled Anxiety, was bound by high loadings of the conflicted ambivalence (.88) and secure (−.61) prototypes. Therefore, the higher an individual's score on the Anxiety factor, the higher their anxious attachment style. The second factor, Avoidance, was bound by high loadings of defensive separation (.81) and excessive dependency (−.66) prototypes. Thus, higher scores on the Avoidance factor reflect a more avoidant attachment style. For each participant, factor scores for these attachment styles were generated and used as predictors in the data analyses described below.

Means and standard deviations for the factor scores are provided in Table 1. Individual ratings on the seven prototype scores were converted into factor scores. Inter-rater reliability was then computed using these two factor scores (Anxiety and Avoidance). Inter-rater reliability analyses for the attachment prototype factor scores (n= 32) revealed fair to good convergence (Intraclass correlation coefficient [ICC] = .71 for the Anxiety factor; ICC = .62 for the Avoidance factor). We found good convergent validity between our factor scores of adult attachment and the Experiences of Close Relationships Scale-Revised (ECR-R; Fraley Waller, & Brennan, 2000) and the Attachment Q-Sort (Kobak, 1989), which were administered to a subset of this sample (ns = 89 and 129, respectively). The Anxiety factor score correlates .39 (p < .001) with informant reports from the anxiety subscale of the ECR-R, −.49 (p < .001) with the security score, and .47 (p < .001) with the preoccupied score from the Q-sort. The Avoidance factor correlates .26 (p < .05) with informant reports from the avoidant subscale of the ECR-R and .31 (p < .001) with the dismissive subscale of the Q-sort.

Interpersonal Problems

The Inventory of Interpersonal Problems (IIP; Horowitz, Rosenberg, Baer, Ureno, & Villasenor, 1988) contains 127 items assessing difficulties in interpersonal relatedness. Items on the IIP are scored on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely distressing). We calculated five scores—interpersonal sensitivity, interpersonal ambivalence, aggression, need for social approval, and lack of sociability— associated with personality disorders (see Pilkonis et al., 1996, for information on the development of these scales). The first three scales discriminate between patients with any personality disorder (PD) diagnosis versus no PD diagnosis. The fourth and fifth scales discriminate between patients with a Cluster C PD and all others. The first scale, interpersonal sensitivity, contains 11 items and includes items that suggest strong affectivity and reactivity: “I am too sensitive to rejection,” “It is hard for me to ignore criticism from other people,” and “I feel too anxious when I am involved with another person.” The second scale, interpersonal ambivalence, contains ten items that reflect content relating to struggling against others and an inability to join collaboratively in either work or love: “It is hard to accept another person's authority over me” or “It is hard to be supportive of another person's goals in life.” The third scale, aggression, contained seven items tapping into active, hostile behavior: “I argue with other people too much” and “I am too aggressive toward other people.” The fourth scale, need for social approval, has nine items that suggest chronic anxiety about the evaluation of others: “I try to please other people too much” or “I worry too much about disappointing other people.” The last scale, labeled lack of sociability, contains ten items that describe problems in socializing and distress in the presence of others: “It is hard to socialize with other people” or “It is hard to feel comfortable around other people.” Alpha coefficients (assessing internal consistency reliability) for each scale were computed and ranged from .85 to .92 for interpersonal ambivalence and lack of sociability, respectively. Means and standard deviations for the sub-scales are provided in Table 1. In the current study, the median correlation among the scales was .52. These scales were originally validated against clinical judgment of presence or absence of different types of personality pathology (see Pilkonis et al., 1996).

Suicide-Related Behaviors

As part of standardized Axis II diagnostic interviews for assessing one of the criterion for borderline personality disorder, clinical evaluators probed patients to report whether or not they had ever: (1) engaged in self-injury without the intent to die (SH) and (2) engaged in a suicide attempt(s) (SA; self-injury with the intent to die). The initial probe for SH was “Have you ever cut, burn, or otherwise injured yourself on purpose without intending to kill yourself?” The initial probe for SA was “Have you ever tried to kill yourself?” Depending on the patients' responses, evaluators were free to ask follow-up questions to determine the likely presence or absence of the behavior and the intent associated with the behavior. To determine intent of the behavior, follow-up questions included assessment of whether or not the person intended to harm her/himself by engaging in the behavior and/or if the person intended to die as a result of the behavior. Follow-up questions included, “Why did you [engage in behavior endorsed]?” and “What was the purpose of [engaging in the behavior endorsed]?” If the participant endorsed at least the presence of some intent to die, the behavior was coded as SA. The behavior was coded as SH when the participant did not intend to die as a result of the behavior but instead wanted to regulate mood, punish self or others, get help from others, and so forth. The outcome and lethality of the suicide-related behavior was not used for the presence of classifying individuals into the NONE, SH, SA, and SA+SH groups.

A team of four judges reviewed these case notes and rated the presence or absence of the behavior (i.e., NONE, SH, SA, or SH+SA). These judges had at least a masters degree in psychology or social work and were trained by the first author (SDS) to code responses to these questions. A subset of cases was randomly selected for reliability ratings (n = 20) and each of the four judges made independent ratings. Reliability analyses revealed excellent agreement for rating of no suicide-related behavior (κ= 1.00), and very good agreement for SA (κ=.75), SH (κ = .64), and the co-occurrence of these behaviors (SH+SA; κ= .83). The overall agreement for these behaviors was also very good (overall κ = .86).

Data Analytic Strategy

We used multinomial logistic regression with Mplus software (Muthén & Muthén, 2004) to compare different categories of self-injurious behaviors to a group that did not engage in any of these behaviors. Multinomial logistic regression is an extension of binary logistic regression, which is the appropriate statistical technique when the outcome variable has three or more values. In this study, our outcome variable has four values (i.e., NONE, SH, SA, and SH+SA). This technique breaks up the regression analysis into a series of binary regressions comparing each group (SH, SA, and SH+SA) to a baseline group (NONE). Thus, with NONE as the baseline group, multinomial regression assesses the odds of being in the SH group vs. the NONE group, the odds of being in the SA group vs. the NONE group, and the odds of being in the SH+SA group vs. the NONE group. To ensure that the effects of the predictors were independent of demographic variables, we controlled for sex, age, and ethnicity.

Mediation occurs when the relation between two variables can be explained (at least partially) by a path through a third, or intervening, variable. The relations among the variables must be embedded within a theoretical rationale to ensure construct validity. Two ways to test the mediated effect are: (1) to test the significance of the difference in the effect of the predictor on the outcome with and without the intervening variable (e.g., Baron & Kenny, 1986), and (2) to test the significance of the product of the unstandardized coefficients from the predictor to the intervening variable and the intervening variable to the outcome (e.g., Sobel, 1982). Researchers have demonstrated that testing the product of the coefficients yields more statistical power than the Baron and Kenny causal steps method (MacKinnon, Lock-wood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002). Thus, we used the unstandardized regression coefficients predicting interpersonal problems from attachment styles and those predicting interpersonal problems to suicide-related behavior to calculate the significance of the indirect effect.

Results

Interpersonal problems were tested as potential mediators of the effects of attachment style on suicide-related behavior. We estimated a multinomial logistic regression model predicting suicide-related behavior group from sex, ethnicity, attachment styles, and interpersonal problems. The first part of the model tested attachment styles in predicting interpersonal problems. Consistent with research demonstrating the deleterious effects of anxious attachment, the Anxiety factor predicted higher levels of all interpersonal problems (after adjusting for sex, age, and ethnicity). The Avoidance factor negatively predicted interpersonal sensitivity, need for social approval, and lack of sociability. Results regarding the prediction of interpersonal problems are shown in Table 2.

TABLE 2. Multinomial Logistic Regression Model: Predicting Interpersonal Problems from Attachment Styles.

| Sensitivity | Ambivalence | Aggression | Need for Social Approval | Lack of Sociability | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variables | B | Adjusted ORa | 95% CIb | B | Adjusted ORa | 95% CIb | B | Adjusted ORa | 95% CIb | B | Adjusted ORa | 95% CIb | B | Adjusted ORa | 95% CIb |

| Intercept | 1.91*** | 6.75 | 4.89, 9.32 | .79*** | 2.20 | 1.63, 2.95 | 1.24*** | 3.46 | 2.49, 4.76 | 2.00*** | 7.39 | 4.89, 10.97 | 1.52*** | 4.57 | 2.92, 7.09 |

| Sex | −.23 | .79 | .68, .92 | −.24*** | .79 | .69, .90 | −.17* | .84 | .72, .99 | −.25*** | .78 | .65, .94 | −.35*** | .70 | .58, .86 |

| Age | .00 | 1.00 | .99, 1.01 | .00 | 1.00 | 1.00, 1.01 | .00 | 1.00 | .99, 1.00 | .00 | 1.00 | .99, 1.01 | .00 | 1.00 | .99, 1.01 |

| Ethnicity | .01 | 1.01 | .87, 1.17 | .10 | 1.11 | .99, 1.24 | .04 | 1.04 | .91, 1.20 | .03 | 1.03 | .89, 1.19 | .10 | 1.11 | .92, 1.32 |

| Attachment Anxiety | .34*** | 1.40 | 1.30, 1.52 | .23*** | 1.26 | 1.17, 1.35 | .40*** | 1.49 | 1.37, 1.63 | .19*** | 1.21 | 1.09, 1.33 | .21*** | 1.23 | 1.10, 1.37 |

| Attachment Avoidance | −.25*** | .78 | .72, .85 | .00 | 1.00 | .93, 1.08 | −.09 | .91 | .84, 1.00 | −.29*** | .75 | .67, .83 | −.12* | .89 | .79, .99 |

Adjusted OR = adjusted odds ratio, or the odds ratio adjusted for the effects of other predictors in the regression model.

95% CI = 95% confidence intervals around the odds ratios; Lower 2.5%, Upper 2.5%.

p<.05,

p<.01,

p< .001.

Results for the total model are presented in Table 3. The values in this table represent the direct effects for the model. Females had higher odds of being in the SH+SA group versus the group with no suicide-related behavior (NONE). As age increased, the odds decreased of being in either the SH+SA group or the SH group versus the NONE group. We tested the relation of attachment styles to self-injury groups. Female sex and age (but not ethnicity) increased the odds of being in all suicide-related behavior groups versus the NONE group. After adjusting for sex, age, and ethnicity, anxious attachment style increased the odds of being in all three suicide-related behavior groups versus the NONE group. However, the avoidant attachment style had a more limited impact, decreasing the odds of being in the SH+SA group versus the NONE group.

TABLE 3. Multinomial Logistic Regression Predicting the Contrasts Among Suicide-Related Behavior Groups from the Covariates, Attachment Styles, and Interpersonal Problems.

| SH+SA vs. NONE | SH vs. NONE | SA vs. NONE | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent variables | B | Adjusted ORa | 95% CIb | B | Adjusted ORa | 95% CIb | B | Adjusted ORa | 95% CIb |

| Intercept | −1.85 | .16 | .02, 1.01 | −1.22 | .30 | .04, 2.16 | −2.13** | .12 | .03, .52 |

| Sex | −.78* | .46 | .23, .94 | −.70 | .50 | .23, 1.09 | −.01 | .99 | .50, 1.96 |

| Age | −.05** | .95 | .91, .99 | −.09*** | .91 | .88, .95 | −.02 | .98 | .95, 1.02 |

| Ethnicity | .53 | 1.70 | .87, 3.32 | .22 | 1.25 | .58, 2.65 | .11 | 1.12 | .68, 1.83 |

| Attachment Anxiety | 1.73*** | 5.64 | 3.43, 9.23 | .65* | 1.92 | 1.11, 3.29 | .71** | 2.03 | 1.31, 3.19 |

| Attachment Avoidance | −.42* | .66 | .44, .99 | −.06 | .94 | .60, 1.47 | −.17 | .84 | .59, 1.21 |

| Sensitivity | .91* | 2.48 | 1.09, 5.61 | 1.55** | 4.71 | 1.81, 12.24 | .25 | 1.28 | .63, 2.62 |

| Ambivalence | −.58 | .56 | .29, 1.06 | .15 | 1.16 | .56, 2.42 | −.04 | .96 | .56, 1.64 |

| Aggression | −.58* | .56 | .35, .90 | −.86** | .42 | .24, .74 | −.19 | .83 | .48, 1.43 |

| Need for Social Approval | .08 | 1.08 | .60, 1.93 | −.31 | .73 | .41, 1.31 | −.09 | .91 | .53, 1.57 |

| Lack of Sociability | .47* | 1.60 | 1.01, 2.51 | .60* | 1.82 | 1.04, 3.16 | .58* | 1.79 | 1.23, 2.85 |

Adjusted OR = adjusted odds ratio, or the odds ratio adjusted for the effects of other predictors in the regression model.

95% CI = 95% confidence intervals around the odds ratios; Lower 2.5%, Upper 2.5%.

p<.05.

p < .01.

p< .001.

In the same model (after adjusting for the effects of demographic variables and attachment styles), interpersonal sensitivity increased the odds of being either in the SH+SA or the SH groups versus the NONE group. Interpersonal aggression decreased the odds of being in either the SH+SA or the SH groups versus the NONE group. Lack of sociability increased the odds of being in all three suicide-related behavior groups versus the NONE group. However, interpersonal ambivalence and need for social approval did not affect the odds of being in any suicide-related behavior group.

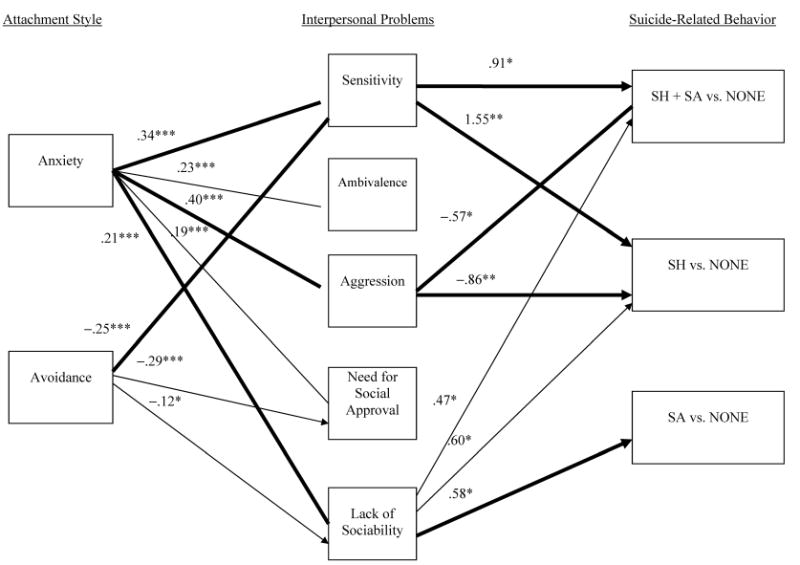

We then used the coefficients from the multinomial logistic regression to test the significance of the indirect (mediated) paths (i.e., attachment styles → interpersonal problems → suicide-related behaviors) for each pairwise suicide-related behavior group comparison. To test the significance of the indirect effects, we conducted Sobel's test for mediation (Sobel, 1982). We also calculated the proportion of the total effect of attachment style on the outcome that was indirect through interpersonal problems (MacKinnon, Warsi, & Dwyer, 1995). Results are depicted in Figure 1, in which bold lines represent significant indirect effects.

Figure 1.

Interpersonal problems as a mediator in the relations between attachment style and suicide-related behavior. The numbers presented are the unstandardized regression coefficients obtained from the multinomial logistic regression predicting contrasts between categories of suicide-related behavior from attachment and interpersonal problems (sex, ethnicity, and age were controlled). Only the significant indirect pathways are shown. The bold lines represent significant mediational pathways. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

There was a significant indirect effect of anxious attachment style through interpersonal sensitivity for the contrasts of SH+SA versus NONE (z = 2.05, 42.60% mediated) and SH versus NONE (z = 2.97, 89.63% mediated). There was also a significant indirect effect of anxious attachment style through interpersonal aggression for the contrasts of SH+SA versus NONE (z = −2.29, 35.80% mediated) and SH versus NONE (z = −2.87, 85.03% mediated). The indirect effect of anxious attachment style through lack of sociability was also significant for the contrast between SA versus NONE (z = 2.04, 14.36% mediated). There was only one significant indirect effect of avoidant attachment style through interpersonal sensitivity for the contrasts of SH+SA versus NONE (z = −1.99, 34.94% mediated) and SH versus NONE (z = −2.80, 86.21% mediated).

Discussion

We examined interpersonal problems as a mediator of the effects of attachment style on suicide-related behaviors in a predominantly psychiatric sample. We tested whether or not specific interpersonal problems would mediate differentially the relations between attachment and SH, SA, and SH+SA groups when compared to those who did not engage in these behaviors.

Interpersonal Problems as a Mediator

The first finding of interest was that attachment styles predicted more fine-grained interpersonal problems and suicide-related behaviors. Specifically, anxious attachment style was associated with all the IIP-PD scales: interpersonal sensitivity, interpersonal ambivalence, interpersonal aggression, need for social approval, and lack of sociability. Additionally, avoidant attachment style was associated with lower levels of interpersonal sensitivity, need for social approval, and lack of sociability. Avoidant attachment style did not have significant relations with interpersonal ambivalence or interpersonal aggression. Secondly, attachment style predicted suicide-related behavior. Anxious attachment increased the risk for all three groups of suicide-related behaviors. However, avoidant attachment was associated with only one group, decreasing the risk for engaging in both self-harm and suicide attempt behaviors.

Interpersonal problems mediated the distal risk of attachment style associated with engaging in suicide-related behaviors. Specifically, higher anxious attachment predicted interpersonal sensitivity, interpersonal aggression, and lack of sociability, which in turn were associated with suicide-related behavior. Additionally, there was a negative association between avoidant attachment and interpersonal sensitivity, which in turn increased the risk for self-injury. Thus, the effects of attachment style on self-injury can be accounted for, in part, by more specific interpersonal problems. These results are consistent with studies demonstrating that insecure attachment styles and interpersonal problems are predictive of suicide-related behaviors (e.g., Adam et al., 1996; Brown et al., 2002; Klonsky et al., 2003; Violato & Arato, 2004; Welch & Linehan, 2002). The current study extends these findings by incorporating both adult attachment styles (a distal risk factor for psychopathology) and more specific interpersonal problems (a more proximal cause) in an overarching framework to identify potential risk factors and underlying mechanisms of suicide-related behaviors.

Differential Pathways from Attachment Styles to Self-Harm, Suicide Attempts, and Their Combination

An important contribution of the present study is the distinction among the suicide-related behaviors of self-harm, suicide attempts, and their combination in examining mediational pathways. We found that specific interpersonal problems were more likely to characterize different groups of individuals engaging in suicide-related behaviors. Specifically, individuals with an anxious attachment style and high interpersonal sensitivity were more likely to engage in SH and SH+SA. Additionally, individuals with an anxious attachment style and low interpersonal aggression were also more at risk for engaging in SH and SH+SA. These findings support those by Klonsky et al. (2003) who demonstrated the connection between suicide-related behavior and worrying about social rejection. By contrast, those who were anxiously attached and who had reduced sociability in adulthood were more likely to engage in SA. This finding is consistent with the interpersonal theory of completed suicide and supports the notion that social isolation increases risk for suicide (e.g., Stellrecht et al., 2006). This finding is also consistent with the notion that failure to belong to a social group results in an inability to be productive and healthy (e.g., Baumeister & Leary, 1995). These results support the general idea that separate interpersonal problems might underlie the development and maintenance of self-injury and suicide attempts (e.g., Linehan, 1997; Nock & Kessler, 2006).

Why should interpersonal sensitivity and (lack of) interpersonal aggression put individuals at risk for suicide-related behavior? It is plausible that individuals with interpersonal problems related to feeling easily hurt or rejected (i.e., interpersonal sensitivity) and being unable to assert their own needs (i.e., low interpersonal aggression) confront an intense approach/avoidance dilemma. They are oriented toward contact with others (approach motivation that belies a wish to die) but they are also profoundly pessimistic about the outcome of such contact, given their attachment insecurity. Such a conflict may diminish the prospects of effective interpersonal behavior, limiting such individuals to intrapersonal solutions to their dilemma. The consequences may frequently be emotional (e.g., heightened levels of depression) but, in some cases, they may be more egregious, leading to suicide-related behavior. These speculations are consistent with Chapman, Gratz, and Brown (2006), who proposed that self-injury is maintained via a negative reinforcement cycle based on the avoidance of emotional experiencing. Additionally, the finding that less interpersonal aggression (lack of assertiveness) increases risk for suicide-related behavior is consistent with the idea that individuals who self-injure may not have the required social skills to navigate interpersonal relationships and could use self-injury as a way to communicate distress. This finding is consistent with research demonstrating that influencing others serves as one function for engaging in suicide-related behaviors (see Klonsky, 2007, for a review).

Another finding of interest is that the same interpersonal problems put individuals at risk for both SH and SH+SA, whereas a separate mechanism puts individuals at risk for engaging in SA alone. This finding suggests that individuals who engage in either SH or SH+SA may be amenable to different treatment interventions than those who engage in SA only. Although this study does not answer the question of whether or not individuals who engage in SA only will go on to develop SH, future research should address the development of the co-occurrence of these behaviors. Researchers examining the functions of self-harm have found that self-injury without the intent to die can serve many functions, including interpersonal communication, affective regulation, antidissociation, antisuicide, and self-punishment functions (see Klonsky, 2007, for a review). These functions are different than that of attempting suicide in order “to make others better off.”

Strengths, Limitations, and Implications

Strengths of the study include the multi-method and intensive assessment process, the distinction between categories of suicide-related behaviors, and the provision of a theoretically coherent interpersonal context for self-injury. By demonstrating that separate interpersonal problems may underlie these different classes of behaviors, this study highlights the importance of distinguishing between them. Additionally, we used clinician assessment of lifetime social and relationship functioning and then relied on a consensus model of rating attachment prototypes. The interpersonal problems were assessed via self-report questionnaire, making these ratings independent of the clinical judgments. Finally, elucidating an interpersonal framework is an important contribution for understanding suicide-related behavior.

The results of this research are not without limitations. First, this study was cross-sectional and relied on reports of retrospective reports of self-injurious behaviors. It might be that individual's change their perception about the intent of suicide-related behavior over time. Moreover, we did not assess for frequency or severity of the suicide-related behaviors, and future research is needed to understand how interpersonal problems are related to these parameters of these behaviors. Lastly, a number of additional potential mediators were not included in the model. Future research will need to examine the effect of interpersonal problems as mediational pathways when controlling for competitive mediators, such as affective lability and normal and pathological personality variants.

Importantly, the causal assumptions underlying these analyses cannot be confirmed directly, but it is plausible that a transactional relationship occurs between self-injury and interpersonal processes such that those who are interpersonally sensitive are more likely to engage in SH and SH+SA, which in turn also increase interpersonal sensitivity, making future self-injury more likely. In future studies, we plan to examine a state-trait model of interpersonal processes and self-injury prospectively to better elucidate the dynamic nature of these constructs.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Institute on Mental Health Grants R01 MH44672 and R01 MH56888 awarded to the last author (PL PA Pilkonis).

References

- Adam KS, Sheldon-Keller AE, West M. Attachment organization and history of suicidal behavior in clinical adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:264–272. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.2.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth MD, Blehar M, Waters E, Wall S. Patterns of attachment. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew K, Horowitz LM. Attachment styles among young adults: A test of a four-category model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;61:226–244. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.2.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Leary MR. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachment as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117:497–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blatt SJ, Auerbach JS, Levy KN. Mental representations in personality development, psychopathology, and the therapeutic process. Review of General Psychology. 1997;1:351–374. [Google Scholar]

- Blatt SJ, Levy KN. Attachment theory, psychoanalysis, personality development, and psychopathology. Psychoanalytic Inquiry. 2003;23:102–150. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan KA, Clark CL, Shaver PR. Self-report measurement of adult attachment: An integrative overview. In: Simpson JA, Rholes WS, editors. Attachment theory and close relationships. New York: Guilford Press; 1998. pp. 46–76. [Google Scholar]

- Brown MZ, Comtois KA, Line-han MM. Reasons for suicide attempts and nonsuicidal self-injury in women with borderline personality disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:198–202. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.1.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brumbaugh CC, Fraley RC. Transference and attachment: How do attachment patterns get carried forward from one relationship to the next? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2006;32:552–560. doi: 10.1177/0146167205282740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy J, Mohr JJ. Unsolvable fear, trauma, and psychopathology: Theory, research, and clinical considerations related to disorganized attachment across the lifespan. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2001;8:275–298. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman AL, Gratz KL, Brown MZ. Solving the puzzle of deliberate self-harm: The experiential avoidance model. Behavior Research and Therapy. 2006;44:371–394. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong M. Attachment, individuation, and risk of suicide in late adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1992;21:357–373. doi: 10.1007/BF01537023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. User's guide for the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV Axis I disorders (SCID-I, Version 2.0) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. User's guide for the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV personality disorders (SCID-II, Version 2.0) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Fonagy P, Leigh T, Steele M, Steel H, Kennedy R, Mattoon G, et al. The relation of attachment status, psychiatric classification and response to psychotherapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:22–31. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.1.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraley RC. Attachment stability from infancy to adulthood: Meta-analysis and dynamic modeling of developmental mechanisms. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2002;6:123–151. [Google Scholar]

- Fraley RC, Waller NG, Brennan KA. An item-response theory analysis of self-report measures of adult attachment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;78:350–365. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.2.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo LC, Smith TW, Ruiz JM. An interpersonal analysis of adult attachment style: Circumplex descriptions, recalled developmental experiences, self-representations, and interpersonal functioning in adulthood. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2003;71:141–181. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.7102003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson JG. Borderline patient's intolerance of aloneness: Insecure attachments and therapist availability. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1996;153:752–758. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.6.752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurtman MB. The circumplex as a tool for studying normal and abnormal personality: A methodological primer. In: Stack S, Lorr M, editors. Differentiating normal and abnormal personality. New York: Springer; 1994. pp. 243–263. [Google Scholar]

- Hazan C, Shaver P. Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;52:511–524. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.52.3.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heape CL, Pilkonis PA, Lambert J, Proietti JM. Interpersonal relations assessment. Department of Psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh; Pittsburgh: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz LM, Rosenberg SE, Baer BA, Ureno G, Villasenor VS. Inventory of interpersonal problems: Psychometric properties and clinical applications. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1988;56:885–892. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howat S, Davidson K. Parasuicidal behaviour and interpersonal problem-solving performance in older adults. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2002;41:375–386. doi: 10.1348/014466502760387498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehrer CA, Linehan MM. Interpersonal and emotional problem-solving skills and parasuicide among women with borderline personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders. 1996;10:153–163. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Borges G, Walters EE. Prevalence of and risk factors for lifetime suicide attempts in the national comorbidity survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1999;56:617–626. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.7.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky ED. The functions of self-injury: A review of the evidence. Clinical Psychology Review. 2007;27:226–239. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky ED, Oltmanns TF, Turkheimer E. Deliberate self-harm in a nonclinical population: Prevalence and psychological correlates. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:1501–1508. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.8.1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobak R. The attachment interview q-set. University of Delaware; 1989. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Levy KN, Blatt SJ. Attachment theory and psychoanalysis: Further differentiation within insecure attachment patterns. Psychoanalytic Inquiry. 1999;19:541–575. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM. Behavioral treatments of suicidal behaviors: Definitional obfuscation and treatment outcomes. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1997;836:302–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb52367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM, Chiles JA, Egan KJ, Devine RH, Laffaw JA. Presenting problems of parasuicides versus suicide ideators and nonsuicidal psychiatric patients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1986;54:880–881. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.54.6.880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM, Rizvi SL, Welch SS. Psychiatric aspects of suicidal behavior: Personality disorders. In: Hawton K, van Heeringen K, editors. The international handbook of suicide and attempted suicide. New York: Wiley; 2000. pp. 147–178. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Warsi G, Dwyer JH. A simulation study of mediated effect measures. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1995;30:41–62. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3001_3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus (Version 3.0) [Computer software] Los Angeles: Author; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Kessler RC. Prevalence of and risk factors for suicide attempts versus suicide gestures: Analysis of the national comorbidity survey. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2006;115:616–623. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.3.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfohl B, Blum N, Zimmerman M. Structured interview for DSM-IV personality. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Pilkonis PA. Personality proto-types among depressives: Themes of dependency and autonomy. Journal of Personality Disorders. 1988;2:144–152. [Google Scholar]

- Pilkonis PA, Heape CL, Proietti JM, Clark SW, McDavid MD, Pitts TE. The reliability and validity of two structured diagnostic interviews for personality disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1995;52:1025–1033. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240043009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilkonis PA, Kim Y, Proietti JM, Barkham M. Scales for personality disorders developed from the inventory of interpersonal problems. Journal of Personality Disorders. 1996;10:355–369. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt S, Nachtigall C, Wuethrich-Martone O, Strauss B. Attachment and coping with chronic disease. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2002;53:763–773. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00335-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman MM, Berman AL, Sanddal ND, O'Carroll PW, Joiner TE. Rebuilding the tower of Babel: A revised nomenclature for the study of suicide and suicidal behaviors. Part 1: Background, rationale, and methodology. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2007a;37:248–263. doi: 10.1521/suli.2007.37.3.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman MM, Berman AL, Sanddal ND, O'Carroll PW, Joiner TE. Rebuilding the tower of Babel: A revised nomenclature for the study of suicide and suicidal behaviors. Part 2: Suicide-related ideations, communications, and behaviors. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2007b;37:264–277. doi: 10.1521/suli.2007.37.3.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel ME. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. In: Leinhardt S, editor. Sociological methodology 1982. Washington, DC: American Sociological Society; 1982. pp. 290–312. [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe LA. Attachment and development: A prospective, longitudinal study from birth to adulthood. Attachment & Human Development. 2005;7:349–367. doi: 10.1080/14616730500365928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stellrecht NE, Gordon KH, Van Orden K, Witte TK, Wingate LR, Cukrowicz KC, et al. Clinical applications of the interpersonal-psychological theory of attempted and completed suicide. Journal of Clinical Psychology: In Session. 2006;62:211–222. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss BM, Lobo-Drost AJ, Pilkonis PA. Einschatzung von Bindungsstilen bei Erwachsenen: Erste Erfahrungen mit der deutschen Version einer Prototypenbeurteilung. [Evaluation of attachment styles among adults: First experiences with the German version of a prototype rating system]. Zeitschrift fur Klinische Psychologie, Psychiatrie und Psychotherapie. 1999;47:347–422. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss B, Kirchmann H, Eckert J, Lobo-Drost A, Marquet A, Papenhausen R, et al. Attachment characteristics and treatment outcome following inpatient psychotherapy: Results of a multisite study. Psychotherapy Research. 2006;16:579–594. [Google Scholar]

- van der Kolk BA, Perry JC, Herman JL. Childhood origins of self-destructive behavior. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1991;148:1665–1671. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.12.1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Merrill KA, Joiner TE. Interpersonal-psychological precursors to suicidal behavior: A theory of attempted and completed suicide. Current Psychiatry Reviews. 2005;1:187–196. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn BE. Discovering pattern in developing lives: Reflections on the Minnesota study of risk and adaptation from birth to adulthood. Attachment and Human Development. 2005;7:369–380. doi: 10.1080/14616730500365944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Violato C, Arato J. Childhood attachment and adolescent suicide: A step-wise discriminant analysis in a case-comparison study. Individual Differences Research. 2004;2:162–168. [Google Scholar]

- Ward MJ, Lee SS, Polan HJ. Attachment and psychopathology in a community sample. Attachment & Human Development. 2006;8:327–340. doi: 10.1080/14616730601048241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch SS, Linehan MM. High-risk situations associated with parasuicide and drug use in borderline personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2002;16:561–569. doi: 10.1521/pedi.16.6.561.22141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright J, Briggs S, Behringer J. Attachment and the body in suicidal adolescents: A pilot study. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005;10:477–491. [Google Scholar]

- Yeomans FE, Levy KN. An object relations perspective on borderline personality disorder. Acta Neuropsychiatrica. 2002;14:76–80. doi: 10.1034/j.1601-5215.2002.140205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]