Abstract

The aim of this study was to determine the effects of antioxidants, including α-ketoacids (α-ketoglutarate and pyruvate), lactate and glutamate/malate combination, against oxidative stress on rat spermatozoa. Our results showed that H2O2 (250 μmol L−1)-induced damages, such as impaired motility, adenosine triphosphate (ATP) depletion, inhibition of sperm protein phosphorylation, reduced acrosome reaction and decreased viability, could be significantly prevented by incubation of the spermatozoa with α-ketoglutarate (4 mmol L−1) or pyruvate (4 mmol L−1). Without exogenous H2O2 in the medium, the addition of pyruvate (4 mmol L−1) significantly increased the superoxide anion (O2−·) level in sperm suspension (P ≤ 0.01), whereas the addition of α-ketoglutarate (4 mmol L−1) and lactate (4 mmol L−1) significantly enhanced tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins with the size of 95 kDa (P ≤ 0.04). At the same time, α-ketoglutarate, pyruvate, lactate, glutamate and malate supplemented in media can be used as important energy sources and supply ATP for sperm motility. In conclusion, the present results show that α-ketoacids could be effective antioxidants for protecting rat spermatozoa from H2O2 attack and could be effective components to improve the antioxidant capacity of Biggers, Whitten and Whittingham media.

Keywords: α-ketoacids, antioxidants, oxidative stress, reactive oxygen species

Introduction

The influence of oxidative stress on male fertility is one of the most important issues in reproductive biology research in the past decade 1, 2. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) mainly include three families: oxygen ions, free radicals and peroxides 3. Superoxide anion (O2−·) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) are the common forms of ROS. Some studies suggested that relatively low concentrations of ROS are beneficial for the normal functions of sperm capacitation 4, but excessively high concentrations of ROS are associated with lower acrosin activity 5, sperm DNA fragmentation, impaired sperm motility 6, 7, decrease in sperm acrosome reaction and fusiogenic ability 8. Clinical studies showed that oral antioxidant treatment appeared to improve sperm DNA integrity and outcomes of in vitro fertilization with intracytoplasmic sperm injection among patients with sperm DNA damage or other male infertility 9, 10. In asthenozoospermia patients, the high level of ROS in semen may be associated with the downregulation of a DJ-1 protein, which is involved in the control of oxidative stress 11.

The damage induced by high concentrations of ROS can be prevented by ROS-scavenging enzymes mainly including superoxide dismutase, catalase and glutathione peroxidase. Superoxide dismutase and catalase were shown to improve sperm survival, reduce ROS generation in boar spermatozoa and prevent human sperm membrane lipid peroxidation during freeze-thaw procedures 12, 13. Catalase had pronounced effects on improving the post-thaw quality of canine spermatozoa and the overall functional parameters of human spermatozoa 14, 15. Glutathione peroxidase activity was shown to be important against lipid peroxidation in human spermatozoa because lipid peroxidation increased significantly either through the inhibition of glutathione peroxidase action or by depleting glutathione availability 16. However, in some cases, ROS-scavenging enzymes have no effect in protecting or even negative effects on sperm. For example, catalase did not improve the maintenance of motility during the storage of liquid equine semen at 5°C 17. Furthermore, the addition of superoxide dismutase in the cryopreservation extender did not decrease ROS level, but rather increased DNA fragmentation 18.

Owing to the disadvantages of ROS-scavenging enzymes, some small molecules, such as α-ketoacids, were used as candidate antioxidants. Pyruvate and lactate were used to maintain the normal adenosine triphosphate (ATP) levels of human spermatozoa when damage was artificially induced by H2O2 6. de Lamirande and Gagnon 6 suggested the role of pyruvate was to rescue the glycolysis pathway, although the authors did not discuss the antioxidant property of pyruvate. In the human breast cancer cell line, Nath et al. 19 showed that α-ketoacids can scavenge copious amounts of H2O2 generated by menadione and reduce menadione-induced DNA injury and cytotoxicity. Meanwhile, Upreti et al. 20 found that, in ram spermatozoa, pyruvate regulated the activity of aromatic amino acid oxidase, the enzyme responsible for generation of H2O2, but they did not further investigate the effect of pyruvate against oxidative stress. To date, the exact role of pyruvate and the effect of α-ketoglutarate in protecting spermatozoa from ROS attack are not yet clear.

Some amino acids can also serve as antioxidants. Treatment of rat liver mitochondria with 500 μmol L−1 tert-butyl hydroperoxide (tert-BuOOH, a strong oxidant) resulted in a reduction of ketoglutarate dehydrogenase activity, which led to the disturbance of the tricarboxylic acid cycle and the decrease in ATP synthesis 21. After the simultaneous addition of glutamate/malate, tert-BuOOH did not inhibit rat liver mitochondria respiration even at very high concentrations (500–1 000 μmol L−1 ) 21. Thus, the combination of glutamate/malate may be a good antioxidant.

In this study, we determined the effects of α-ketoglutarate, pyruvate, lactate and glutamate/malate as potential antioxidants against oxidative stress on rat spermatozoa in the presence of exogenous H2O2.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and animals

Luminol (5-amino-2,3-dihydro-1,4-phthalazinedione) and lucigenin (bis-N-methylacridinium nitrate), anti-phosphotyrosine monoclonal antibody (PY20), monoclonal anti-α-tubulin antibody and Chlortetracycline (CTC) hydrochloride were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA). 2-methyl-6-(4-methoxyphenyl)-3,7-dihydroimidazo[1,2-a]pyrazin-3-one-hydrochloride (MCLA) was purchased from TCI America (Portland, OR, USA). Horseradish peroxidase (HRP, 300 U mg−1), catalase (3 kU mg−1), superoxide dismutase (1.4 kU mg−1) and Protease Inhibitor Cocktail were purchased from Sangon (Shanghai, China). ATP assay kit was purchased from Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology (Haimen, China). Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail was purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA, USA). Transgreen and propidium iodide (PI) were a kind gift from Professor Hui-Juan Shi.

A total of 40 male Sprague-Dawley rats (weighting 400–500 g) were purchased from Laboratory Animal Center (Shanghai, China). All animal studies were carried out according to local and national guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals and approved by the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of Shanghai Institute of Biological Sciences.

Experimental design

Experiments were conducted in the presence or absence of exogenous H2O2. The presence of H2O2 was used to simulate oxidative stress, whereas the absence of H2O2 was used to determine whether antioxidants have negative effects on spermatozoa. After spermatozoa were treated with various antioxidants and H2O2 for various time periods, the effects of antioxidants were evaluated by examining ROS levels, ATP levels, tyrosine phosphorylation, motility, acrosome reaction and viability.

Preparation of rat spermatozoa

Rats were killed by cervical dislocation or using 10% choral hydrate, and then spermatozoa were released from the caudal epididymides into 3 mL modified Biggers, Whitten and Whittingham (mBWW, free of pyruvate and lactate) medium (NaCl 94.7 mmol L−1, KCl 4.8 mmol L−1, CaCl2 1.71 mmol L−1, KH2PO4 1.2 mmol L−1, MgSO4·7H2O 1.2 mmol L−1, NaHCO3 25 mmol L−1, glucose 5.6 mmol L−1, HEPES 20 mmol L−1, penicillin 60 mg L−1, streptomycin 100 mg L−1, pH 7.6) 22. The concentration of bovine serum albumin in mBWW medium was 0 mg mL−1 for ROS levels assay using MCLA, 15 mg mL−1 for tyrosine phosphorylation and acrosome reactions, and 4 mg mL−1 for other experiments. Spermatozoa were prepared by the swim-up method and incubated at 37°C with an atmosphere of 5% CO2. Sperm density of 1 × 107–2 × 107 and 2 × 106–3 × 106 cells per mL was used for ROS levels assay using MCLA and other experiments, respectively.

Measurement of ROS levels by chemiluminescence

After 1 h of incubation, ROS levels in treated samples were examined. Luminol + HRP and lucigenin were used to examine H2O2-treated samples, whereas MCLA was used to analyze samples without H2O2 treatment. Samples supplemented with catalase (0.2 mg mL−1) or superoxide dismutase (0.1 mg mL−1) were used as controls to confirm that the detected chemiluminescence signals were specific to ROS. Protocols for measuring ROS levels using luminol + HRP, lucigenin and MCLA were described elsewhere 23, 24. The working concentration of luminol and lucigenin was 250 μmol L−1, whereas that of HRP and MCLA was 12 U mL−1 and 20 μmol L−1, respectively. Chemiluminescent signals were recorded in 400 μL of solution or sperm suspension on an LB9507 luminometer (Berthold Technologies, Bad Wildbad, Germany) using a capture time of 10 s in integration mode. The background level was subtracted as described 24. Data are expressed as relative light units.

Sperm motility analysis

Motility was examined by computer-assisted sperm analysis (CASA) using an HTM-IVOS system (version 10.8, Hamilton-Thorne Research, Beverley, MA, USA). Images of sperm tracks were captured in a 100-μm chamber for 0.5 s at 60 Hz. Five arbitrary and independent fields were chosen for sperm-motility examination. At least 500 tracks were measured for each specimen at 37°C.

Examination of sperm ATP content

The process was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. At the end of 1-h incubation, 200 μL of sperm suspension was centrifuged at 800 × g for 5 min. Sperm pellets were lyzed in 200 μL of lysis buffer. Then 100 μL of the lyzed sperm solution and 100 μL of luciferin–luciferase reagent were mixed for 3 s before luminescence was measured for 10 s using the GloMax 20/20 luminometer (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The signal intensities were normalized by setting the control value at 100%. Results are expressed as relative ATP levels.

Sperm viability assay

Dual staining with Transgreen/PI was used to examine sperm viability 25. Transgreen (5 μmol L−1) and PI (5 mg mL−1) were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide and phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), respectively. The sperm suspension (500 μL) was incubated with 1 μL of Transgreen and PI for 15 min at 37°C before examination. Transgreen/PI is excited at 488 nm. The green fluorescence was collected through 525-nm band pass filters. The red fluorescence was collected through 635-nm band-pass filters. Quantitative data on the fluorescently stained sperm populations were collected by FACS using a Calibur LSRII (BD Biosciences, Monona, WI, USA). A total of 10 000 spermatozoa were analyzed, and their viability was expressed as the log of fluorescent intensity for each sample. The generated data were analyzed using the WinMDI 2.9 software (TSRI, La Jolla, CA, USA).

Determination of protein tyrosine phosphorylation

At the end of a 5-h incubation, treated samples were collected and washed twice with PBS. Sperm pellets were resuspended in sample buffer containing phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (1 mmol L−1), Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (diluted at 1:1 000), Na3VO3 (1 mmol L−1) and Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail (diluted at 1:100), and incubated at 100°C for 5 min. Sperm proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis on 10% gels and transferred onto nitrocellulose transfer membranes. The membranes were probed with PY20 at 4°C overnight, followed by incubation with a goat anti-mouse IgG, HRP conjugate. An internal control protein was detected with an anti-α-tubulin antibody. Detection of proteins was performed using an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (Thermo Scientific, Madison, WI, USA). The films were scanned using a Luminescent Image Analyzer LAS4000 (Fujifilm, Mishima, Japan). Digital images obtained were analyzed by Multi Gauge V3.0 software (Fujifilm). The intensities were normalized to 1 with the value obtained in capacitating spermatozoa (control group). In all cases, the contribution of the background was subtracted.

Evaluation of sperm acrosome reaction

Spermatozoa were treated with H2O2 and various chemicals for 4 h at 37°C under 5% CO2 atmosphere, stained with chlortetracycline (CTC) and assessed for sperm acrosome reaction as described elsewhere 26, 27. After CTC staining and fixation, more than 200 cells per sample were examined at original magnification of × 1 000 using an Olympus BX51 fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Statistical analysis

One-way analysis of variance (two tailed; paired values) and Tukey's test were used to evaluate the motility, ATP level, acrosome reaction and viability. For ROS level and tyrosine phosphorylation assay, a two-tailed Student's t-test was used to compare spermatozoa under control and different treatments. Data analyses were carried out using the SPSS V17.0 software (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). A difference was considered statistically significant with P < 0.05 26, 28, 29.

Results

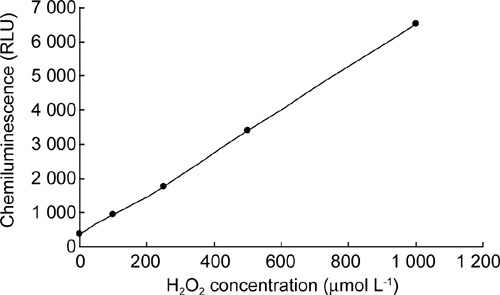

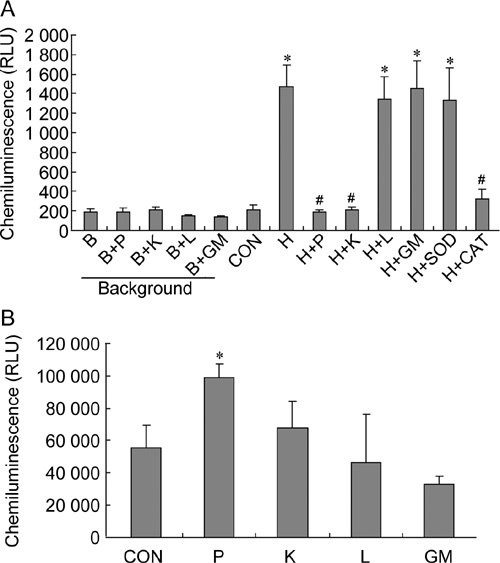

ROS levels in sperm suspension were measured by a chemiluminescence assay. Lucigenin was used to detect H2O2 and O2−·, and the linear relationship between lucigenin-dependent chemiluminescence signals and H2O2 concentrations was observed in our study (Figure 1). ROS levels in samples treated by H2O2, H2O2 + lactate, H2O2 + glutamate/malate and H2O2 + superoxide dismutase were significantly higher than those in the control (P < 0.001) (Figure 2A). ROS levels in samples treated with H2O2 + pyruvate, H2O2 + α-ketoglutarate and H2O2 + catalase were similar to that of the control (Figure 2A). Only pyruvate significantly enhanced (P ≤ 0.01) the production of ROS in the absence of exogenous H2O2 in sperm suspension as determined by MCLA to detect O2−· (Figure 2B).

Figure 1.

Standard curve measured by lucigenin for H2O2. Various concentrations of H2O2 were prepared in mBWW medium and then were measured using lucigenin (250 μmol L−1).

Figure 2.

Effects of antioxidants on reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels in sperm suspensions. (A): ROS levels were assayed using lucigenin. (B): ROS levels were assayed using MCLA. B, mBWW; P, pyruvate (4 mmol L−1); K, α-ketoglutarate (4 mmol L−1); L, lactate (4 mmol L−1); GM, glutamate/malate (4 mmol L−1); CON, control; H, H2O2 (250 μmol L−1); SOD, superoxide dismutase (0.1 mg mL−1); CAT, catalase (0.2 mg mL−1). *P < 0.05, compared with control; #P < 0.001, compared with H sample; (n = 3).

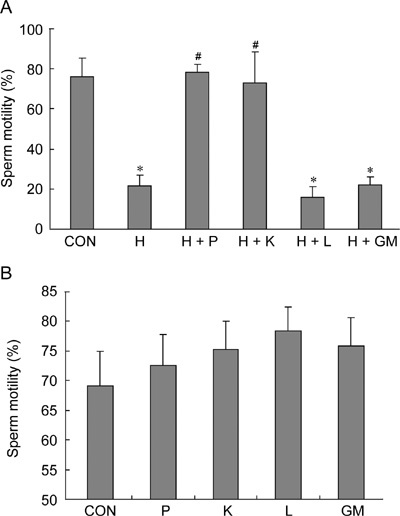

Sperm motility was determined at the end of a 1-h treatment (Figure 3A). H2O2 caused reduction of sperm motility to 22%, which was significantly lower than that of the control (76%) (P < 0.001). Motility of the samples supplemented with pyruvate and α-ketoglutarate were maintained at 77% and 66%, respectively. Motility in the samples treated with lactate and glutamate/malate (16% and 23%, respectively) were significantly lower than the control (P ≤ 0.003). In the absence of H2O2 in the sperm suspension, pyruvate, α-ketoglutarate, lactate and glutamate/malate had an apparent positive effect on motility after a 5-h incubation, but the degree of improvement was not statistically significant (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Effects of antioxidants on sperm motility. (A): Sperm motility was examined at the end of a 1-h treatment using computer-assisted sperm analysis (CASA). (B): Sperm motility was examined at the end of a 5-h treatment using CASA. CON, control; H, H2O2 (250 μmol L−1); P, pyruvate (4 mmol L−1); K, α-ketoglutarate (4 mmol L−1); L, lactate (4 mmol L−1); GM, glutamate/malate (4 mmol L−1). *P < 0.001, compared with control; #P < 0.01, compared with H sample; (n = 4).

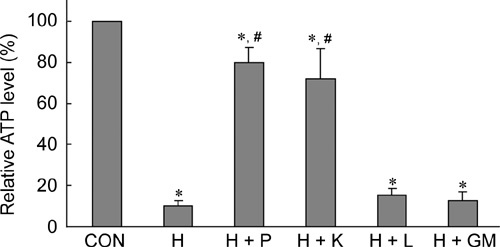

ATP levels in all H2O2-treated (250 μmol L−1) samples were significantly lower than the control (P ≤ 0.002) (Figure 4). H2O2 caused significant loss of ATP in spermatozoa. The samples treated with only H2O2 had ATP levels at 10% that of the control group. Supplementation of pyruvate and α-ketoglutarate allowed the maintenance of sperm ATP at 80% and 72%, respectively, which were significantly higher than those treated with H2O2 only (P < 0.001). Lactate and glutamate/malate had no distinct effect on restoring sperm ATP levels.

Figure 4.

Effects of antioxidants on adenosine triphosphate (ATP) levels. ATP levels were assayed at the end of a 1-h treatment. CON, control; H, H2O2 (250 μmol L−1); P, pyruvate (4 mmol L−1); K, α-ketoglutarate (4 mmol L−1); L, lactate (4 mmol L−1); GM, glutamate/malate (4 mmol L−1). *P< 0.01, compared with control; #P < 0.001, compared with H sample; (n= 4).

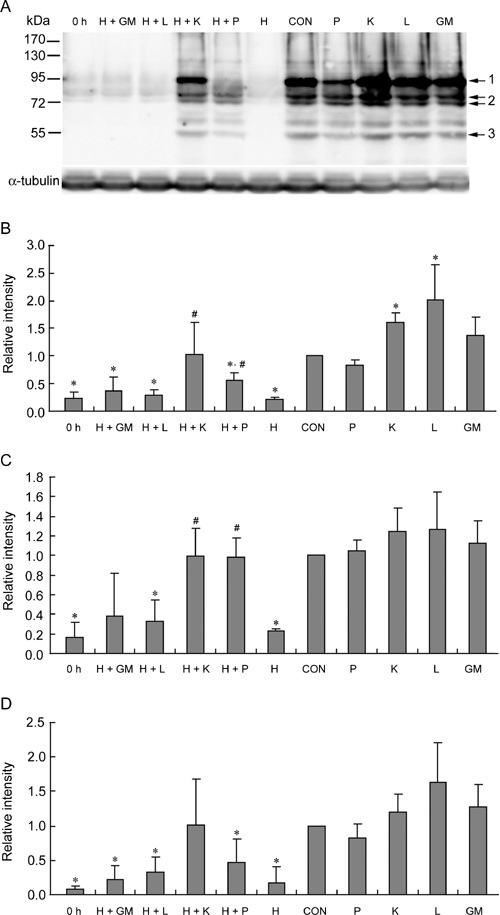

The effects of antioxidants and H2O2 on protein tyrosine phosphorylation were determined at the end of a 5-h incubation period using PY20, an anti-phosphotyrosine antibody (Figure 5). The quantitative data (Figure 5B–D) showed that H2O2 (250 μmol L−1) significantly inhibited tyrosine phosphorylation (P ≤ 0.005). Pyruvate and α-ketoglutarate significantly restored the 95- and two 80-kDa bands (P ≤ 0.04). The 55-kDa band was also restored to certain levels by pyruvate and α-ketoglutarate. Lactate and glutamate/malate had no marked effect on restoring tyrosine phosphorylation. In the absence of exogenous H2O2 in the media, α-ketoglutarate, lactate and glutamate/malate improved tyrosine phosphorylation, whereas only the 95-kDa band was significantly enhanced by α-ketoglutarate and lactate (P ≤ 0.03). Pyruvate had a slight negative effect on the 95- and 55-kDa bands, and no effect on the two 80-kDa bands.

Figure 5.

Effects of antioxidants on tyrosine phosphorylation. (A): Western blot assay was performed at the end of a 5-h treatment. (B): Quantification of the 95-kDa bands indicated by arrow 1. (C): Quantification of the two 80-kDa bands indicated by arrow 2. (D): Quantification of the 55-kDa bands indicated by arrow 3. 0 h, control sample incubated for 0 h. CON, control; H, H2O2 (250 μmol L−1); P, pyruvate (4 mmol L−1); K, α-ketoglutarate (4 mmol L−1); L, lactate (4 mmol L−1); GM, glutamate/malate (4 mmol L−1). *P < 0.05, compared with control; #P < 0.05, compared with H sample; (n = 4).

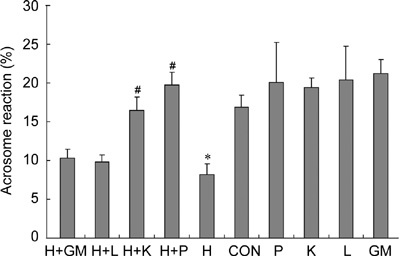

Analysis of acrosome reaction using CTC staining showed H2O2 (250 μmol L−1) causing significant inhibition when compared with control (P ≤ 0.01) (Figure 6). All the antioxidants used in this study restored acrosome reaction to certain levels. α-Ketoglutarate and pyruvate significantly restored acrosome reaction compared with samples treated with H2O2 only (P ≤ 0.02). Without H2O2 treatment, acrosome reaction was improved by these antioxidants, but the degree of improvement was not statistically significant (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Effects of antioxidants on acrosome reaction. Acrosome reaction was assayed at the end of a 4-h treatment using CTC staining. CON, control; H, H2O2 (250 μmol L−1); P, pyruvate (4 mmol L−1); K, α-ketoglutarate (4 mmol L−1); L, lactate (4 mmol L−1); GM, glutamate/malate (4 mmol L−1). *P < 0.05, compared with control; #P < 0.05, compared with H sample; (n = 3).

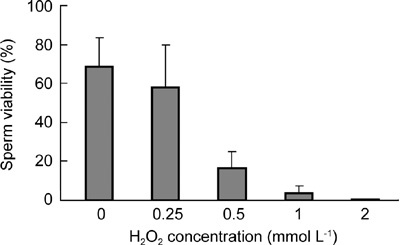

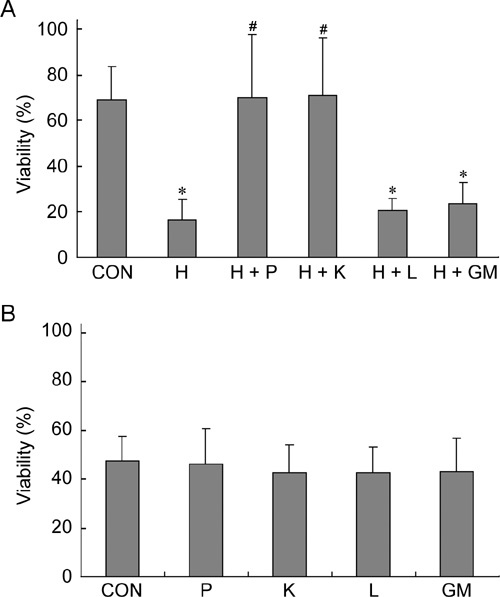

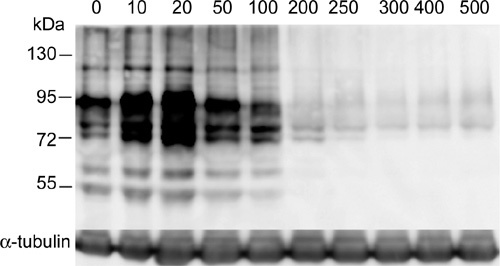

First, effects of various concentrations of H2O2 on rat sperm viability were determined at the end of a 4-h treatment (Figure 7). With increasing concentrations of H2O2, sperm viability gradually decreased. H2O2 at a concentration of 500 μmol L−1 significantly decreased sperm viability compared with control (P < 0.001) (Figure 8A). Sperm viability in H2O2-treated samples supplemented with pyruvate and α-ketoglutarate was restored to 70% and 71%, respectively; however, the sperm viability was only 21% and 24% when supplemented with lactate and glutamate/malate, respectively, which was significantly lower than the control (P ≤ 0.007). Without H2O2 treatment, sperm viability was similar among the groups treated with various antioxidants for 24 h at room temperature (Figure 8B).

Figure 7.

The effects of various concentrations of H2O2 on sperm viability. Rat spermatozoa were incubated with various concentrations of H2O2 for 4h and then viability was assayed using Transgreen/PI staining.

Figure 8.

Effects of antioxidants on sperm viability. (A): Sperm viability was examined at the end of a 4-h treatment using Transgreen/PI staining. (B): Sperm viability was examined at the end of a 24-h treatment using same technique. CON, control; H, H2O2 (500 μmol L−1); P, pyruvate (4 mmol L−1); K, α-ketoglutarate (4 mmol L−1); L, lactate (4 mmol L−1); GM, glutamate/malate (4 mmol L−1). *P < 0.01, compared with control value; #P < 0.01, compared with H sample. (n = 4).

Discussion

Supplementation of sperm incubation media with antioxidants has often been suggested as a way of reducing ROS-induced damage to spermatozoa. The aim of this study was to examine the protective effects of candidate antioxidants α-ketoglutarate, pyruvate, lactate, and glutamate/malate on protecting rat spermatozoa from ROS attack. The H2O2-induced damage in this study may be representative of ROS damage encountered during the incubation before in vitro fertilization or other sperm functional tests.

The luminol probe can measure both intracellular and extracellular ROS, especially O2−·, H2O2 and OH− free radicals, whereas lucigenin can detect extracellular ROS, especially O2−· and OH− free radicals 23, 30. We first tried to measure ROS levels in H2O2-treated samples using luminol, but did not obtain reliable data because the luminol-dependent chemiluminescent signals were quenched too fast when it was added to the mBWW medium containing H2O2 (Table 1). We found that lucigenin-dependent chemiluminescence signals and concentrations of H2O2 have a linear relationship. Furthermore, lucigenin-dependent chemiluminescent signals could be eliminated by catalase instead of superoxide dismutase. Therefore, lucigenin was used to examine H2O2-treated samples in this study.

Table 1. Examination of H2O2 using luminol. Various concentrations of H2O2 were prepared in mBWW medium and then were measured using luminol (250 μmol L−1) + horseradish peroxidase (HRP).

| Time point (s) | H2O2 concentration (μmol L−1) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 10 | 50 | 100 | 250 | |

| 10 | 1 660 RLU | 9 933 RLU | overload | overload | overload |

| 30 | 216 RLU | 245 RLU | 1 260 RLU | overload | overload |

| 50 | 163 RLU | 158 RLU | 400 RLU | 1 116 RLU | overload |

| 70 | 138 RLU | 131 RLU | 323 RLU | 632 RLU | overload |

| 90 | 129 RLU | 137 RLU | 281 RLU | 520 RLU | overload |

Abbreviation: RLU, relative light units.

As lucigenin could produce an artificial signal when measuring superoxide production 31, MCLA was used to measure O2−· levels in samples without H2O2 treatment in this study. Results showed that pyruvate enhanced the production of O2−· in sperm suspension, although the mechanism of this enhancement is unclear.

Sperm motility was rather depleted after a 1-h incubation with H2O2. Impaired sperm motility was associated with a loss of intracellular ATP, as ROS could inhibit the activities of enzymes in the tricarboxylic acid cycle, such as aconitase and ketoglutarate dehydrogenase 6, 32. Our ATP levels assay showed that ATP level in H2O2-treated samples was only 10% of the untreated samples (Figure 4). Besides the antioxidant role, the addition of pyruvate in media would replenish ATP for motility 6. α-Ketoglutarate, lactate, glutamate and malate were also important energy sources to supply ATP for sperm motility 33.

The positive role of ROS as regulators of protein tyrosine phosphorylation has been shown 29, 34, 35. These studies were performed with the physiological concentrations of ROS or endogenous ROS. Effects of various concentrations of H2O2 on rat sperm protein tyrosine phosphorylation were determined, as shown in Figure 9. Low concentrations of H2O2, such as 10 or 20 μmol L−1, enhanced tyrosine phosphorylation, but high concentrations of H2O2 (more than 100 μmol L−1) had negative effects. The inhibition effect of H2O2 (250 μmol L−1) on tyrosine phosphorylation could be reversed with the addition of pyruvate or α-ketoglutarate, not lactate and glutamate/malate, in sperm suspension at the beginning of the treatment.

Figure 9.

The effects of various concentrations of H2O2 (μmol L−1) on sperm protein tyrosine phosphorylation. Rat spermatozoa were incubated with various concentrations of H2O2 for 5h and then tyrosine phosphorylation was assayed using PY20 antibody. α-Tubulin was a 55-kDa protein and used as internal control.

Very little is known about the role of the components in BWW media on tyrosine phosphorylation. Our data indicated pyruvate had a slight negative effect on tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins with sizes of 95 and 55 kDa. α-Ketoglutarate, lactate and glutamate/malate had an improved role on tyrosine phosphorylation and the 95-kDa band was significantly enhanced by α-ketoglutarate and lactate. The mechanism of the enhancement of tyrosine phosphorylation by antioxidants involves the production of endogenous ROS. Although both H2O2 and α-ketoglutarate stimulate tyrosine phosphorylation, they probably regulate the activity of tyrosine kinase through different pathways because α-ketoglutarate mainly enhanced the 95-kDa proteins and H2O2 enhanced all the tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins. Tyrosine phosphorylation in rat sperm was driven by ROS acting through two different but complementary mechanisms 36. O2−· stimulates tyrosine kinase activity indirectly through the elevation of intracellular cAMP, whereas H2O2 acts directly on the kinase/phosphatase system, stimulating the former and inhibiting the latter 36.

de Lamirande et al. 28 showed that both O2−· and H2O2 were involved in the regulation of human sperm acrosome reaction. In bovine spermatozoa, low concentrations of H2O2 could be an inducer of acrosome reaction and high concentrations of H2O2 (250 μmol L−1) had a deleterious effect 37. Our results showed that H2O2 (250 μmol L−1) could also reduce rat sperm acrosome reactions and the addition of pyruvate or α-ketoglutarate in sperm suspension at the beginning of incubation could completely prevent this reduction.

H2O2 (250 μmol L−1) had marked effect on some sperm functions and only a weak effect on viability after a 4-h treatment. H2O2 (500 μmol L−1) caused a dramatic decrease in sperm viability, which could be prevented by the supplementation of pyruvate or α-ketoglutarate (P ≤ 0.001). Except for the antioxidant roles, pyruvate and α-ketoglutarate could be used as an energy source for sperm motility and survival.

α-Ketoacids quench H2O2 mainly through the reaction of nonenzymatic oxidative decarboxylation 19. In this reaction, α-ketoglutarate is converted to succinate, which would support the tricarboxylic acid cycle 38. Thus, α-ketoglutarate can shunt the tricarboxylic acid cycle on inactivation of ketoglutarate dehydrogenase under oxidative stress. In addition, α-ketoglutarate may also shunt the tricarboxylic acid cycle by the α-aminobutyrate shunt metabolic pathway 39. However, the reaction of pyruvate with H2O2 results in the formation of acetate, which cannot enter the tricarboxylic acid cycle 21. Recently, Mailloux et al. 38 found that the tricarboxylic acid cycle was also an integral part of the oxidative defense machinery in cells, and α-ketoglutarate was a key participant in the detoxification of ROS. Therefore, α-ketoglutarate as an effective antioxidant will protect spermatozoa through multiple pathways.

To determine the roles of pyruvate and lactate, mBWW media (free of pyruvate and lactate) was used in this study. Normal BWW media contain a certain amount of pyruvate (27 μmol L−1) and lactate (23.6 mmol L−1) 22. The main roles of lactate in BWW are as an energy source. Owing to the low concentration of pyruvate, BWW has a weak antioxidant capacity. If high concentrations of pyruvate or α-ketoglutarate were supplemented in the BWW medium, the antioxidant capacity of BWW media will be enhanced.

In conclusion, our results indicate that α-ketoacids has an important role in protecting sperm from the injury induced by H2O2 and they could be effectively used to improve the antioxidant capacity of BWW media.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the Major State Basic Research Development Program of China (973 Program) (No. 2007CB947100) and the Shanghai Municipal Commission for Science and Technology, China (No. 074319111 and No. 07DZ22919). We thank Yi-Hong Wang for his help in animal experiments and Professor Hui-Juan Shi for her kind donation of Transgreen and PI.

References

- Aitken RJ.Sperm function tests and fertility Int J Androl 20062969–75.discussion 105–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aitken RJ, Baker MA. Oxidative stress and male reproductive biology. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2004;16:581–8. doi: 10.10371/RD03089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremellen K. Oxidative stress and male infertility—a clinical perspective. Hum Reprod Update. 2008;14:243–58. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmn004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivlin J, Mendel J, Rubinstein S, Etkovitz N, Breitbart H. Role of hydrogen peroxide in sperm capacitation and acrosome reaction. Biol Reprod. 2004;70:518–22. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.020487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalata AA, Ahmed AH, Allamaneni SS, Comhaire FH, Agarwal A. Relationship between acrosin activity of human spermatozoa and oxidative stress. Asian J Androl. 2004;6:313–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lamirande E, Gagnon C. Reactive oxygen species and human spermatozoa. II. Depletion of adenosine triphosphate plays an important role in the inhibition of sperm motility. J Androl. 1992;13:379–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aitken RJ, Harkiss D, Buckingham D. Relationship between iron-catalysed lipid peroxidation potential and human sperm function. J Reprod Fertil. 1993;98:257–65. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0980257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa T, Oeda T, Ohmori H, Schill WB. Reactive oxygen species influence the acrosome reaction but not acrosin activity in human spermatozoa. Int J Androl. 1999;22:37–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2605.1999.00145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menezo YJ, Hazout A, Panteix G, Robert F, Rollet J, et al. Antioxidants to reduce sperm DNA fragmentation: an unexpected adverse effect. Reprod Biomed Online. 2007;14:418–21. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)60887-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremellen K, Miari G, Froiland D, Thompson J. A randomised control trial examining the effect of an antioxidant (Menevit) on pregnancy outcome during IVF-ICSI treatment. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;47:216–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2007.00723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Zhang HR, Shi HJ, Ma D, Zhao HX, et al. Proteomic analysis of seminal plasma from asthenozoospermia patients reveals proteins that affect oxidative stress responses and semen quality. Asian J Androl. 2009;11:484–91. doi: 10.1038/aja.2009.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roca J, Rodriguez MJ, Gil MA, Carvajal G, Garcia EM, et al. Survival and in vitro fertility of boar spermatozoa frozen in the presence of superoxide dismutase and/or catalase. J Androl. 2005;26:15–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi T, Mazzilli F, Delfino M, Dondero F. Improved human sperm recovery using superoxide dismutase and catalase supplementation in semen cryopreservation procedure. Cell Tissue Bank. 2001;2:9–13. doi: 10.1023/A:1011592621487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael A, Alexopoulos C, Pontiki E, Hadjipavlou-Litina D, Saratsis P, et al. Effect of antioxidant supplementation on semen quality and reactive oxygen species of frozen-thawed canine spermatozoa. Theriogenology. 2007;68:204–12. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2007.04.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi HJ, Kim JH, Ryu CS, Lee JY, Park JS, et al. Protective effect of antioxidant supplementation in sperm-preparation medium against oxidative stress in human spermatozoa. Hum Reprod. 2008;23:1023–8. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez JG, Storey BT. Role of glutathione peroxidase in protecting mammalian spermatozoa from loss of motility caused by spontaneous lipid peroxidation. Gamete Res. 1989;23:77–90. doi: 10.1002/mrd.1120230108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball BA, Medina V, Gravance CG, Baumbe J. Effect of antioxidants on preservation of motility, viability and acrosomal integrity of equine spermatozoa during storage at 5 degrees C. Theriogenology. 2001;56:577–89. doi: 10.1016/s0093-691x(01)00590-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumber J, Ball BA, Linfor JJ. Assessment of the cryopreservation of equine spermatozoa in the presence of enzyme scavengers and antioxidants. Am J Vet Res. 2005;66:772–9. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.2005.66.772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nath KA, Ngo EO, Hebbel RP, Croatt AJ, Zhou B, et al. alpha-Ketoacids scavenge H2O2in vitro and in vivo and reduce menadione-induced DNA injury and cytotoxicity. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:C227–36. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.268.1.C227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upreti GC, Jensen K, Munday R, Duganzich DM, Vishwanath R, et al. Studies on aromatic amino acid oxidase activity in ram spermatozoa: role of pyruvate as an antioxidant. Anim Reprod Sci. 1998;51:275–87. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4320(98)00082-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedotcheva NI, Sokolov AP, Kondrashova MN. Nonenzymatic formation of succinate in mitochondria under oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;41:56–64. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation. WHO Laboratory Manual for the Examination of Human Semen and Sperm-Cervical Mucus Interaction4th edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999. p84.

- Aitken RJ, Buckingham DW, West KM. Reactive oxygen species and human spermatozoa: analysis of the cellular mechanisms involved in luminol- and lucigenin-dependent chemiluminescence. J Cell Physiol. 1992;151:466–77. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041510305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lamirande E, Gagnon C. Capacitation-associated production of superoxide anion by human spermatozoa. Free Radic Biol Med. 1995;18:487–95. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(94)00169-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao HX, Yuan Y, Hua MM, Zhang HQ, Shi HJ. Viability assessment of human sperm using Transgreen and propidium iodide. Chinese Journal of Andrology. 2008;22:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Oberlander G, Yeung CH, Cooper TG. Influence of oral administration of ornidazole on capacitation and the activity of some glycolytic enzymes of rat spermatozoa. J Reprod Fertil. 1996;106:231–9. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.1060231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu JH, He XB, Wu Q, Yan YC, Koide SS. Subunit composition and function of GABAA receptors of rat spermatozoa. Neurochem Res. 2002;27:195–9. doi: 10.1023/a:1014876303062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lamirande E, Tsai C, Harakat A, Gagnon C. Involvement of reactive oxygen species in human sperm acrosome reaction induced by A23187, lysophosphatidylcholine, and biological fluid ultrafiltrates. J Androl. 1998;19:585–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Flaherty C, de Lamirande E, Gagnon C. Reactive oxygen species modulate independent protein phosphorylation pathways during human sperm capacitation. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;40:1045–55. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.10.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal A, Allamaneni SS, Said TM. Chemiluminescence technique for measuring reactive oxygen species. Reprod Biomed Online. 2004;9:466–8. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)61284-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford WC. Regulation of sperm function by reactive oxygen species. Hum Reprod Update. 2004;10:387–99. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmh034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tretter L, Adam-Vizi V. Inhibition of Krebs cycle enzymes by hydrogen peroxide: a key role of α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase in limiting NADH production under oxidative stress. J Neurosci. 2000;20:8972–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-24-08972.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb GW, Arns MJ. Effect of pyruvate and lactate on motility of cold stored stallion spermatozoa challenged by hydrogen peroxide. J Equine Vet Sci. 2006;26:406–411. [Google Scholar]

- Ecroyd HW, Jones RC, Aitken RJ. Endogenous redox activity in mouse spermatozoa and its role in regulating the tyrosine phosphorylation events associated with sperm capacitation. Biol Reprod. 2003;69:347–54. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.102.012716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Flaherty C, de Lamirande E, Gagnon C. Positive role of reactive oxygen species in mammalian sperm capacitation: triggering and modulation of phosphorylation events. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;41:528–40. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis B, Aitken RJ. A redox-regulated tyrosine phosphorylation cascade in rat spermatozoa. J Androl. 2001;22:611–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Flaherty CM, Beorlegui NB, Beconi MT. Reactive oxygen species requirements for bovine sperm capacitation and acrosome reaction. Theriogenology. 1999;52:289–301. doi: 10.1016/S0093-691X(99)00129-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mailloux RJ, Beriault R, Lemire J, Singh R, Chenier DR, et al. The tricarboxylic acid cycle, an ancient metabolic network with a novel twist. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e690. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouche N, Fait A, Bouchez D, Moller SG, Fromm H. Mitochondrial succinic-semialdehyde dehydrogenase of the gamma-aminobutyrate shunt is required to restrict levels of reactive oxygen intermediates in plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:6843–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1037532100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]