Abstract

Hacker et al. (in this issue) provide further evidence that molecular subtypes of malignant melanoma may develop along divergent pathways. Hacker et al. did not find an association between somatic BRAF-mutant melanoma and germline melanocortin-1 receptor (MC1R) gene status. We discuss this seeming paradox in light of previous studies showing strong associations.

Keywords: epidemiology, dermatology, etiology, skin pigmentation, oncogene, BRAF, MC1R, melanocortin-1 receptor, melanin, mole, nevus

Introduction

Hacker et al. (2009) contribute new data indicating how BRAF-mutant melanomas can be included (2009) in their previously proposed divergent pathway model for melanoma development. Their findings lend support to BRAF-mutant melanomas developing along a pathway positively associated with young age at diagnosis, high nevus counts, contiguous nevus remnants, and ability to tan and inversely associated with evidence of high level of lifetime cumulative sun exposure. However, Hacker et al. found no association between germline melanocortin-1 receptor (MC1R) status and BRAF-mutant melanomas in an Australian population-based study. These results differ from two earlier publications (Fargnoli et al., 2008; Landi et al., 2006) that reported strong associations in three independent populations (two from Italy and one from San Francisco).

Divergent pathways

The results of Hacker et al. are concordant with many other studies which have found distinct risk factors for melanomas harboring BRAF mutations. Both hospital and population-based studies on different continents have found BRAF mutations to be associated with young age at diagnosis (Edlundh-Rose et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2007; Thomas et al., 2007). Others have reported that BRAF-melanomas were associated with contiguous nevus remnants on histologic sections (Edlundh-Rose et al., 2006; Poynter et al., 2006). Similar to Hacker et al., BRAF-mutant melanomas have been reported to be associated with high back nevus counts and increased ability to tan in a North Carolina population-based study (Thomas et al., 2007). Other studies have found BRAF-mutant melanomas to be inversely associated with chronically exposed anatomic site and solar elastosis, providing further evidence of an inverse association with high levels of cumulative sun exposure (Curtin et al., 2005)

Paradox and possible explanations

Hacker et al. (2009) report no association between germline MC1R variants and BRAF-mutant melanomas in 123 cases from Australia. Similarly, we examined the relationship between MC1R status and BRAF-mutant melanomas in our North Carolina population-based study; and, similar to that of Hacker et al., our results do not support a strong association.1 In contrast, Landi et al. scored independent sets of 86 and 112 melanoma specimens from a case-control study in Italy and a hospital-based series in San Francisco for histologic evidence of chronic sun damage (CSD). The majority, 56 and 58, respectively, did not show CSD. They reported that MC1R variants were strongly associated with BRAF-mutant melanomas in biopsies with little histologic evidence of chronic sun damage (non-CSD) (Landi et al., 2006). More recently, in a separate case-control study in Italy including 92 melanomas typed for BRAF mutations, Fargnoli et al. also found germline MC1R variants to be strongly associated with BRAF-mutations, independent of CSD status (Fargnoli et al., 2008).

There are several possible explanations for the differing results among these studies. First, dissimilar estimates may be due, in part, to unique effects of specific MC1R variants, the frequencies of which differ somewhat among study populations. Secondly, there may be unidentified genotypic variation among populations that affects the association of MC1R variants with BRAF-mutant melanoma. For example, inherited variants in other genes related to pigmentation, tanning response, or nevus propensity might influence this association. Furthermore, environmental differences, in particular ambient sun exposure, could affect the relationship.

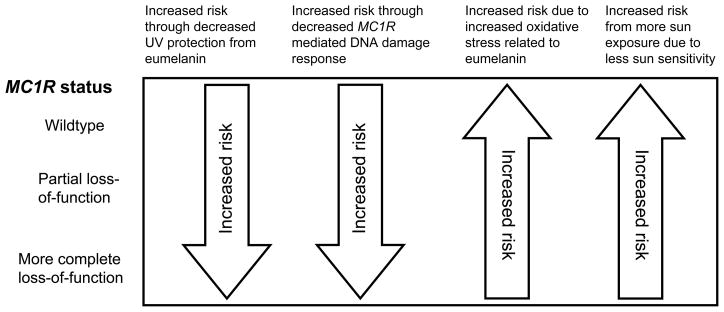

Gene-environment interactions involving MC1R could be quite complex because MC1R functional status alone might have opposing effects on risk of BRAF-mutant melanoma, as shown in Figure 1. In this model, we assume that basal pheomelanin production is the null phenotype of MC1R and that epidermal pheomelanin levels do not vary between the groups based on findings that MC1R mutations reduce eumelanin but do not change pheomelanin concentration in mouse tail epidermis (Van Raamsdonk et al., 2009). Inheritance of decreased function MC1R variants might increase the risk of BRAF-mutant melanoma through diminished constitutive and facultative pigmentation, less effective DNA damage response mechanisms, and increased generation of hydrogen peroxide (Abdel-Malek et al., 2008). However, carriage of more functional MC1R variants might increase risk because eumelanin, as well as pheomelanin, can contribute to oxidative stress (Meyskens et al., 2004), and individuals with more eumelanin may increase their sun exposure due to their relatively decreased sun sensitivity.

Figure 1. Potential opposing effects of MC1R variant status upon risk of BRAF-mutant melanoma.

Functional MC1R allows the production of the darker eumelanin pigment and the tanning response. Carriage of decrease-of-function MC1R variants may allow increased BRAF-mutant melanoma risk through decreased photo-protection by eumelanin and attenuation of DNA damage response mechanisms. In opposition, more functional MC1R variants may increase risk through increased eumelanin leading to more oxidative stress and increase sun exposure due to less sun sensitivity.

Due to these competing effects, it is possible that genotypes with an intermediate loss of MC1R function might produce a favorable host phenotype for production of BRAF-mutant nevi and melanoma. A combination of some eumelanin and decreased DNA damage responses may be most conducive to increased risk of BRAF mutations. Concordant with this possibility is the finding that individuals with more than one MC1R red hair variants (“R/R”) as defined by Duffy et al. tend to have fewer nevi (Duffy et al., 2004), which frequently harbor BRAF mutations. In addition, patients with albinism, who have melanocytes but who do not produce eumelanin, are at low risk of developing melanoma (Ihn et al., 1993). Furthermore, MC1R enhances repair of DNA photoproducts independent of pigmentation (Abdel-Malek et al., 2008), and MC1R variants increase the risk of melanoma even in individuals with darker complexions, a characteristic which normally would be considered protective (Kennedy et al., 2001; Palmer et al., 2000).

Because all studies to date examining the association of MC1R variants with BRAF-mutant melanoma are relatively small, we cannot rule out the possibility that differing results are due to chance alone, and further investigation with larger populations will clarify the relationship. In addition, few MC1R “R/R” participants have been represented in the studies to date, making it difficult to assess the odds of BRAF-mutant melanoma in individuals with very low eumelanin levels with simultaneously decreased DNA damage responses due to their MC1R status. Other genes which regulate tanning responses or pigmentation might be expected to have less influence on eumelanin production in these individuals.

Increased statistical power along with ample representation of different populations, including those with different European ancestries, should help to solve this problem. This work could be approached through larger studies or meta-analyses including diverse populations. Genome-wide association and candidate pathways studies to identify and assess additional inherited melanoma risk factors should provide complementary information. Genotypic variants may be found that are associated with BRAF-mutations or modify the relationship between MC1R variants and BRAF mutations in melanoma. Candidate pathways of interest include those that affect pigment phenotype, tanning response, nevus propensity, and DNA damage response. An increased ability to assign inherited differences and somatic alterations in melanoma to pathways in the divergent pathway model of melanoma development should help our understanding of melanoma risk and lead to better risk prediction and targeted prevention.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center grant, National Cancer Institute grants CA112243 and CA112524, and a National Institute of Environmental Health Science grant ES014635.

Abbreviations

- MC1R

melanocortin-1 receptor

Footnotes

Submitted

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

- Abdel-Malek ZA, Knittel J, Kadekaro AL, Swope VB, Starner R. The melanocortin 1 receptor and the UV response of human melanocytes--a shift in paradigm. Photochem Photobiol. 2008;84:501–508. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2008.00294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaumont KA, Shekar SN, Cook AL, Duffy DL, Sturm RA. Red hair is the null phenotype of MC1R. Hum Mutat. 2008;29:E88–E94. doi: 10.1002/humu.20788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtin JA, Fridlyand J, Kageshita T, Patel HN, Busam KJ, Kutzner H, et al. Distinct sets of genetic alterations in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2135–2147. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy DL, Box NF, Chen W, Palmer JS, Montgomery GW, James MR, et al. Interactive effects of MC1R and OCA2 on melanoma risk phenotypes. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:447–461. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edlundh-Rose E, Egyhazi S, Omholt K, Mansson-Brahme E, Platz A, Hansson J, et al. NRAS and BRAF mutations in melanoma tumours in relation to clinical characteristics: a study based on mutation screening by pyrosequencing. Melanoma Res. 2006;16:471–478. doi: 10.1097/01.cmr.0000232300.22032.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fargnoli MC, Pike K, Pfeiffer RM, Tsang S, Rozenblum E, Munroe DJ, et al. MC1R variants increase risk of melanomas harboring BRAF mutations. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:2485–2490. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihn H, Nakamura K, Abe M, Furue M, Takehara K, Nakagawa H, et al. Amelanotic metastatic melanoma in a patient with oculocutaneous albinism. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:895–900. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(93)70128-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy C, ter Huurne J, Berkhout M, Gruis N, Bastiaens M, Bergman W, et al. Melanocortin 1 receptor (MC1R) gene variants are associated with an increased risk for cutaneous melanoma which is largely independent of skin type and hair color. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;117:294–300. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202x.2001.01421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landi MT, Bauer J, Pfeiffer RM, Elder DE, Hulley B, Minghetti P, et al. MC1R germline variants confer risk for BRAF-mutant melanoma. Science. 2006;313:521–522. doi: 10.1126/science.1127515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Kelly JW, Trivett M, Murray WK, Dowling JP, Wolfe R, et al. Distinct clinical and pathological features are associated with the BRAF(T1799A(V600E)) mutation in primary melanoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:900–905. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyskens FL, Jr, Farmer PJ, Anton-Culver H. Etiologic pathogenesis of melanoma: a unifying hypothesis for the missing attributable risk. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:2581–2583. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-03-0638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer JS, Duffy DL, Box NF, Aitken JF, O'Gorman LE, Green AC, et al. Melanocortin-1 receptor polymorphisms and risk of melanoma: is the association explained solely by pigmentation phenotype? Am J Hum Genet. 2000;66:176–186. doi: 10.1086/302711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poynter JN, Elder JT, Fullen DR, Nair RP, Soengas MS, Johnson TM, et al. BRAF and NRAS mutations in melanoma and melanocytic nevi. Melanoma Res. 2006;16:267–273. doi: 10.1097/01.cmr.0000222600.73179.f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas NE, Edmiston SN, Alexander A, Millikan RC, Groben PA, Hao H, et al. Number of nevi and early-life ambient UV exposure are associated with BRAF-mutant melanoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:991–997. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Raamsdonk CD, Barsh GS, Wakamatsu K, Ito S. Independent regulation of hair and skin color by two G protein-coupled pathways. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2009 Jul 21; doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2009.00609.x. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]