Abstract

The approach to the febrile child is always concerning for any physician despite the fact that most fevers are viral in origin. However, in rare cases, a missed bacterial infection can have serious consequences. How can fevers of viral origin be differentiated from those of bacterial origin? Do all febrile children with no obvious infection site need a blood culture? Should antibiotics be administered before the results of the blood culture have been received? In the past 30 years, there has been an overabundance of recommendations, advice, opinions and suggested treatments on this subject. The purpose of this review is to present the evidence that is known at this time concerning the management of the febrile child and to present one approach used in a large urban paediatric emergency department.

Keywords: Children, Fever, Review

Abstract

La démarche face à l’enfant fiévreux est toujours préoccupante pour le médecin, même si la plupart des fièvres sont d’origine virale. Cependant, dans de rares cas, une infection bactérienne passée inaperçue peut avoir de graves conséquences. Comment peut-on distinguer les fièvres d’origine virale des fièvres d’origine bactérienne? Les enfants fiévreux sans foyer d’infection évident devraient-ils tous subir une hémoculture? Les antibiotiques devraient-ils être administrés avant la réception de l’hémoculture? Depuis 30 ans, une surabondance de recommandations, d’avis, d’opinions et de traitements suggérés ont été émis sur le sujet. La présente analyse vise à présenter les observations probantes connues à l’heure actuelle au sujet de la prise en charge de l’enfant fiévreux et à présenter une démarche utilisée dans un grand département d’urgence pédiatrique en milieu urbain.

In children, fever is generally a sign of infection. Fever due to other causes including malignancy is rare. The prognosis for the most common forms of paediatric infections is usually excellent; these infections are much more likely to be viral (rhinitis, pharyngitis, laryngitis, bronchitis, bronchiolitis, gastroenteritis, exanthems) than bacterial (pneumonia, urinary tract infections [UTIs], sinusitis, tonsillitis, otitis).

The medical history, physical examination and, when necessary, a few additional complementary tests usually lead to a prompt diagnosis. The physician can then prescribe the appropriate treatment if necessary, but more often can reassure the child’s parents that the infection is benign and, therefore, counsel them on which symptoms and signs to look for, and how to relieve the discomfort of a high fever when a viral infection is suspected, as it is in most cases.

In a few children, fever is the only clinical finding. In these cases, the physician is faced with a difficult problem. Most unexplained fevers are of viral origin, but an isolated fever can also be the only obvious manifestation of bacteremia. A febrile child with an occult bacteremia cannot be clinically differentiated from a generally healthy child with a simple viral infection (1). Neither the medical history, the physical examination, nor complementary tests indicate a bacterial infection that can potentially lead to serious complications. It is therefore necessary to wait for the results of a blood culture to confirm the bacteremia.

How can a fever of viral origin be differentiated from one of bacterial origin? Do all febrile children with no obvious infection site need a blood culture? Should antibiotics be administered before the results of the blood culture have been received? In the past 30 years, there has been an over-abundance of recommendations, advice, opinions and suggested treatments on this subject. What should be remembered from a long scientific debate with conclusions that are still uncertain?

BACTEREMIA

In 1967, Belsey (2) reported the first three paediatric cases of bacteremia. Torphy and Ray (3) described 11 other cases in 1970. These initial reports gave most of the clinical characteristics of the disease that are known today: infection mainly due to Streptococcus pneumoniae, appearing most often in children less than three years of age with fever higher than 39°C and leukocytosis higher than 20,000/mm3. Before the development of a vaccine for Haemophilus influenzae type B (Hib), pneumococcal bacteremia was three times more prevalent than Hib bacteremia (4). However, up to 25% of Hib infections were complicated by meningitis (5). Over the past decade, the generalized use of the Hib vaccine has almost eliminated bacteremia and other serious Hib infections (arthritis, cellulitis, epiglottitis and meningitis) (6). In 1998, only 50 cases of invasive Hib disease were recorded in Canada (7).

At the present time, with the virtual disappearance of Hib infections, it is estimated that not quite 4% of children between three and 36 months with a rectal temperature of 39°C or higher and a generally healthy appearance have pneumococcal bacteremia (8). In a recent study performed in children of the same age group with a rectal or tympanic temperature of 39°C or higher, the incidence of various types of bacteremia was 1.6% (1). H influenzae was not among the isolated germs. Over 90% of all bacteremias are caused by pneumococcus (1,5,9). The remaining 10% are caused by various bacterial germs, such as Neisseria meningitidis, nontyphoidal salmonella, group A streptococcus, group B streptococcus, Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus and other more unusual germs (1,9). Meningococcus is the most dangerous of them. Group A streptococcus bacteremias appearing with chickenpox usually occur in children who do not appear well (9). With the widespread use of pneumococcal immunization, the distribution of these agents is likely to be affected.

In the absence of treatment, bacteremias either resolve spontaneously, persist or are complicated by other symptoms. A positive blood culture will not differentiate a bacteremia from a serious active bacterial infection. The most serious complications arising from occult bacteremia often appear before the results of the blood culture are known (10). They include septicemia, meningitis, pneumonia, arthritis, osteomyelitis and cellulitis. The evolution of bacteremia depends primarily on its causal agent.

The usual prognosis for pneumococcus bacteremia is excellent. Most cases (90.3%) resolve completely without treatment (5). Aside from the neonatal period, deaths due to pneumococcus infections are rare in normal children and are almost always the unfortunate outcome of meningitis (11,12). The increase in microbial resistance has had no negative impact on the development and treatment of invasive infections other than meningitis-type infections (12–15). Meningococcus bacteremia is rare but high risk. In the absence of prompt treatment, the speed at which it develops can be rapid. Any delay in treatment can be catastrophic for the child and have serious legal repercussions for the physician (9). The immediate danger arising from meningococcus bacteremia is that it may lead to purpura fulminans, with irreversible septic shock and death. Without treatment or with late treatment, recovery is the exception (16–18). In the absence of purpuric eruption, up to 75% of meningococcus infections remain undetected after the initial examination where the child has been sent home (19).

A number of studies have been done to find and evaluate clinical indicators of bacteremia. A strong indicator of the disease must be present in bacteremic children, and for this indicator to be useful, the frequency with which it appears must be significantly different than in nonbacteremic children. There are no highly reliable indicators known at the present time. This fact can most likely be explained by the complex nature of clinical studies. Investigations are made at different times and in different places; the groups studied are not always homogeneous; data-gathering methods are not standardized; and some statistical analyses are not sufficiently rigorous. No study is truly satisfactory.

AGE

Bacteremia appears at all ages; however, it is more frequent in infants between the ages of three and 36 months. Before the age of three months, the incidence of bacterial disease in febrile infants is about 10% and that of bacteremia is between 2% and 3%. As a rule, bacterial infections are more serious and insidious in infants less than three months. This group, particularly the neonates, is more vulnerable and is exposed to a greater variety of causal agents; group B streptococcus and E coli being the two main ones. The main danger during the neonatal period is for UTI or meningitis (20). In North America, neonatal meningitis caused by Listeria monocytogenes is rare.

TEMPERATURE

Children are considered to be febrile when their rectal temperature reaches or exceeds 38°C while at rest in a comfortable environment and when the child is not wearing excessive clothing (8). In young children, or for a more precise measurement, a rectal temperature is preferable to oral temperature (21). Axillary and tympanic temperature measurements are not as accurate (22). Electronic thermometers give results close to those of a mercury thermometer.

Taking the temperature only shows the child’s degree of fever at a particular moment. A high fever usually urges parents to consult a physician rapidly. However, the physician’s clinical judgement is usually based on the temperature and the general appearance at the time of the examination, not the temperature taken at home. This applies to all children except those younger than three months (23).

The degree of temperature is an important but misleading indicator. Bacteremia is more frequent in children with a temperature of 39°C or higher. The risk of bacterial infection tends to increase with the degree of temperature (21). More often than not, it will be pneumonia or a UTI (24–26) rather than bacteremia or meningitis (27).

The absence of fever or the presence of a low grade fever does not preclude the possibility of a serious infection (21). In the case of normal temperature at the time of the examination but a history of fever, a sepsis examination is indicated for neonates and possibly some infants between the ages of one and three months or if there is the slightest appearance of toxicity (28). It should be noted that an error in reading the temperature, excessive clothing or an overheated room could alter the temperature reading. However, it would be unwise to conclude too hastily that the fever is artificial. A lumbar puncture can be deferred and the infant returned home, if the child can be observed for several hours to ensure the continued absence of fever by repeatedly taking his or her temperature, and if the results of the white blood cell count and urine analysis are normal.

The therapeutic response to antipyretics and the length of the fever do not allow the physician to predict the etiology and seriousness of the infection (21,29). The risk of bacteremia could be slightly higher in children examined within 24 h of the onset of high fever (30). High fever incites parents to consult more rapidly, which can help early detection of any possible bacteremia. Extremely serious infections, such as meningitis or meningococcemia, usually develop in a devastating way in less than 48 h.

In normal children, a simple febrile convulsion is not necessarily indicative of bacteremia or meningitis (31,32). In infants, a third of febrile convulsions are due to the human herpesvirus 6 (33).

GENERAL APPEARANCE OF THE FEBRILE CHILD

By definition, occult bacteremia implies a healthy appearance. Case management becomes more complicated when the clinical impression is ambiguous. An alert and active child with a healthy appearance, who is well hydrated, smiles, cries vigorously but is easily consoled; who watches the physician’s movements, seeks his parents’ hand or their soothing eyes and does not cause worry. These signs are reassuring and usually indicate a benign febrile state. They are the components of the clinical evaluation scale proposed in 1982 by McCarthy et al (34) of Yale University (Table 1). This scale is a good clinical tool for evaluating children between three and 36 months old. It is an objective aid to clinical judgement, and confirms a good or bad impression. However, it is better for measuring the seriousness of obvious clinical signs than the hidden disease. It does not distinguish between fatigue and a septic state. In addition, it is disappointing when evaluating very young infants. For infants younger than three months old, the Rochester criteria is more reliable (Table 2) (35). Strictly applied, it allows a high degree of precision in differentiating children who are at low and high risk of infection (35). However, its use during the first month of life is generally considered to be dangerous (20).

TABLE 1.

Yale criteria for febrile children between three and 36 months

|

Each criterion is given a score of either 1 (normal), 2 (moderate impairment) or 3 (severe impairment). A child with a score of 10 or less is unlikely to have a serious illness (less 2.7%). A child with a score of 16 or more has a great probability of serious illness (up to 92.3%). Data from reference 34

TABLE 2.

Rochester criteria for febrile children between 30 and 90 days

|

Data from reference 35

LEUKOCYTOSIS

Bacterial infections are more likely than viral infections to have a leukocytosis count of 15,000/mm3 or more, but because viral infections are much more frequent than bacterial infections, the majority of febrile children with a high leukocytosis count have a viral infection (10). In healthy children from one to three years of age, the normal white cell count varies between 6000 and 17,500/mm3; in children one month of age it varies between 5000 and 19,500/mm3 (36). It is rightly possible to wonder why the risk level for bacteremia has been set at 15,000/mm3 (37). Pneumococcus tends to cause stronger leukocytotic reactions than do H influenzae and meningococcus. Up to 70% of meningococcemia cases have a circulating white blood cell count lower than 15,000/mm3 (16,19). The leukopenia of serious septicemia usually comes with other alarming symptoms. In a group of children of all ages with extreme leukocytosis (white blood cell count 35,000/mm3 or higher), almost 20% had pneumonia, 10% had bacteremia and 12% had a viral infection (38). Considering the decline in Hib infections, leukocytosis with a white blood cell count under 20,000/mm3 is a more acceptable risk level (39).

The percentage and absolute number of total neutrophils are more precise and useful than those of unsegmented neutrophils (bands) (40). This is because the manual count of bands varies from one laboratory or observer to another and because automated cell counters do not differentiate between neutrophils and unsegmented neutrophils (41). Automated cell counters have the advantage of providing more precise cell counts than do manual counts (41).

Children between three and 36 months of age with an absolute neutrophil count greater than 10,000 cells/m3 are at higher risk of occult pneumococcal bacteremia: 8% compared with 0.8% for those with an absolute neutrophil count less than 10,000 cells/m3 (42).

White blood cell count results can be confusing for physicians when there is an obvious discrepancy between the number of leukocytes and the child’s general condition. In such cases, the clinical aspect is more important than a simple laboratory result.

OTHER MARKERS OF INFECTION

Various bacterial markers have been evaluated and recommended: sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, inter-leukin-8, procalcitonin, etc. Though of some clinical value, they are not in general use for various practical reasons (43–45). A recent study has found C-reactive protein of value in the evaluation of febrile young children (46). C-reactive protein was a more useful marker of serious bacterial infection than the absolute neutrophil count or the white blood cell count in a small study (46). However, its use is still debatable. It is likely to make the decision more confusing when there is a discrepancy between the general appearance of the child and the C-reactive protein result and/or white blood cell count. Its role in a world with less and less pneumococcal infection in the future is unknown.

CHEST X-RAYS

An unexplained and persistent fever can be the only manifestation of pneumonia (47). When faced with high fever and leukocytosis greater than 20,000/mm3, the physician should suspect pneumonia (48). In children younger than four or five years of age, bacterial pneumonias are mainly due to pneumococcus. Up to 26% of children younger than five years old with an unexplained fever of 39°C or higher and leukocytosis 20,000/mm3 or higher, who have no respiratory symptoms, may have a pneumonia that can only be detected by a chest x-ray (48). Between 10% and 30% of pneumococcal pneumonias are related to bacteremia. During the first three months of life, the incidence of pneumococcus infections is very low. In the absence of respiratory symptoms, chest x-rays are usually normal. Opinions vary on the necessity of including chest x-rays in the work-up of febrile newborns showing no site of infection (20,21).

UTIs

The prevalence of urinary infections in infants with unexplained fever varies from 5% to 7.5% (21,49). Repeated spells of fever or normal tympanic membranes following several alleged bouts of otitis media should lead the physician to suspect UTI (47). The diagnosis of a UTI must be confirmed by a culture; it is preferable to take urine specimens by bladder tap or catheterization rather than by a bag because bag specimens are often contaminated. In a recent study, 63% of all bag specimens were contaminated compared with 9% for catheter specimen (50). Thus, febrile infants less than three months of age should either be catheterized or have a bladder tap. Older febrile children who are not toilet-trained and who have a risk factor for a UTI, such as UTI symptoms, UTI past history, known renal anomalies, toxic appearance or who have positive urine analysis by bag specimen should be catheterized (50). Febrile infants older than three months of age who are not toilet-trained and are at low risk of UTI should have a bag specimen taken initially (50).

EMPIRICAL ANTIBIOTIC THERAPY

Empirical antibiotic therapy may reduce the number of serious bacterial complications (51), even though it does not prevent meningitis (5,37). It has not been formally proven that the absence of treatment has ever been the direct cause of a serious accident (10,52). Neither the proponents of empirical treatment nor those of foregoing treatment lack good arguments. The scientific data are contradictory and unclear. Any two experts who carefully read the paediatric literature will be unable to agree on the validity of empirical treatment: the literature will reassure one (53) and leave the other (5) undecided. The choice of antibiotics can also be debated. In one case, amoxicillin is no better than a placebo (54); in another, it has a certain advantage (5). Some physicians hesitate between ceftriaxone and a beta-lactam antibiotic (14); others use ceftriaxone with some reservation (39); still others, after making a few methodological changes, find ceftriaxone superior to amoxicillin (55). Without these questionable changes, however, the advantage disappears, and the therapeutic results of both antibiotics are disappointing (10,56,57).

With the rarity of Hib infections, the usefulness of empirical treatment is even more unsure (10,57). Oral antibiotic therapy cannot prevent the risk of meningitis, but it can delay its diagnosis (5,37). Too liberal a use of ceftriaxone will most likely lead to an increase in the number of resistant strains of bacteria (5). A therapeutic compromise would be to treat children with an ambiguous general appearance who have not had an anti-Hib vaccine, whose fever is 40°C or more, who have a high count of leukocytosis and who do not seem to be under optimal observation at home (5,56).

“Fever is not caused by a deficit in ceftriaxone” (58). Ceftriaxone is not a panacea, nor is it total risk insurance. It is an expensive drug that is administered intravenously or intramuscularly in a painful way.

The widespread use of pneumococcal immunization in the near future will likely reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with pneumococcal bacteremias (40,59). This will decrease the difference in outcome between the different approaches: observation in comparison to the approach of empirical treatment for all patients or based on an elevated white blood cell count (59). Efficacious and widespread use of pneumococcal immunization will likely favour the observational approach based on clinical judgement (40,59).

APPROACH TO THE CHILD WITH A POSITIVE BLOOD CULTURE

It is possible to get the results of a truly positive blood culture within 24 h because pneumococcus and meningococcus cultures usually grow faster than those of H influenzae. The results of false-positive blood cultures come in later. The main contaminating germs are coagulase-negative Staphylococcus and Streptococcus viridians (60).

When faced with a positive blood culture, the physician’s approach should depend on the virulence of the germ, the persistence or not of fever and the child’s general condition. Hospitalization is not the rule. However, careful follow-up must be done.

Children in good general health who have had no fever for several hours and in whom pneumococcus has been found can be treated at home (8). The absence of fever at the time of examination does not preclude the existence of persisting bacteremia (10). The rarity of Hib infections and the strong unlikelihood of a meningococcus bacteremia in the absence of fever and other anomalies render it unnecessary to perform another blood culture if the child has regained his usual appearance and behaviour. In geographical areas with a high level of resistant pneumococcus strains, high dose amoxicillin or parenteral ceftriaxone allows the physician to wait for the results of the bacterial sensitivity test. If the child is already taking amoxicillin, the treatment should be continued. Any other type of bacteremia, regardless of the child’s condition, should be treated in a hospital with parenteral antibiotic therapy. Home treatment for exceptional Hib bacteremia can be considered under certain conditions: normal child, absence of fever for the past 24 h, excellent general condition, resumption of routine activities, good family environment and available antibiotic sensitivity.

Nearly 20% of blood cultures are falsely positive. These cultures are costly in many respects: they add to the parents’ worry; they cause salary losses for one or more members of the family and impose painful experiences on the child (hospitalization, additional laboratory tests, intravenous access); they prolong or call for useless antibiotic therapy; and they promote drug allergies. The best way to prevent contamination of blood cultures is to reduce their clinical use (60).

CASE MANAGEMENT STRATEGIES

In 1993, a group of experts wrote practice guidelines for managing children up to 36 months old presenting with a fever and no site of infection (53,61). This guide, which was published simultaneously in two medical journals, was widely read and provoked many comments and criticisms (5,10,56,62). It is an academic work based on studies of uneven quality that were made before the introduction of the anti-Hib vaccine. The guide puts too much focus on the risk indicators of bacteremia, and it is not necessarily adapted to everyday practice. For these and other reasons, the guide has not received the full support of practitioners (63). Other approaches have been published (35,64–66) and were briefly summarized recently (67). Models have also been presented (68,69).

The various available guides never precisely match the numerous clinical situations that exist, but they can support a hesitant diagnostic approach or validate a therapeutic preference (9,20,39,53,70,71).

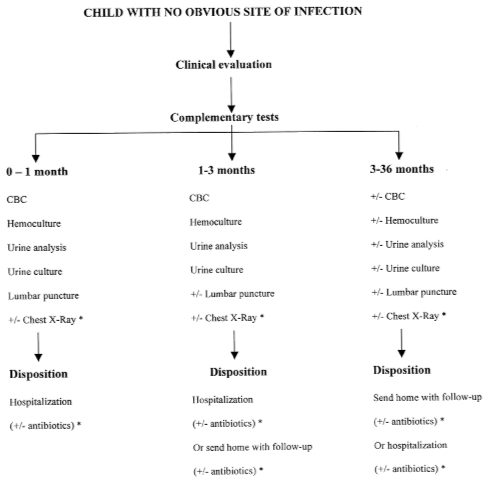

Our approach described below is based on the analysis of the medical literature (Figure 1). It is also based on the vast clinical experience acquired over the years by the staff paediatricians in our emergency department that had an annual census of 70,000 to 85,000 children per year in the past 20 years.

Figure 1).

Management strategy in febrile children when there is no obvious site of infection. CBC Complete blood count; ± With or without. *Usually withheld unless symptom or sign (see text for discussion)

For infants younger than than 30 days old, the safest approach remains a complete and systematic sepsis examination (complete blood count [CBC], blood culture, urine analysis and culture and lumbar puncture) followed by hospitalization for observation with or without empirical treatment (Figure 1). In these cases, age is the determining factor, regardless of the appearance or behaviour of the newborn. Chest x-ray is usually withheld unless the child has respiratory symptoms or signs. Empirical treatment may be withheld in some cases if the newborn has an excellent appearance, the complementary tests (leukocyte count, urine analysis, cerebrospinal fluid analysis) are all within normal range and if there is a good chance that the etiology of the fever is viral (positive family history particularly during summer time). However, in the majority of cases, empirical treatment is the rule.

For infants between one and three months old, it is better to be too conservative than too rash: a CBC, blood culture, and urine analysis and culture should be done (Figure 1). In these cases, the difference in infection risk levels is not as clear as it is for other age groups. In hazardous situations (uncertain clinical judgement, unclear complementary tests, troubled parents, distant home), hospitalization is preferable. Chest x-ray is usually withheld unless the infant has respiratory symptoms or signs. Lumbar puncture is also usually withheld if the clinician is reassured by the general appearance of the infant unless there is doubt about the possibility of a bulging fontanel or the level of irritability of the infant. When the situation is favourable, (normal child, excellent general condition, fever well tolerated, normal leukocyte count, normal urine analysis, good family environment, assurance of fast medical supervision), returning the child to his home should be considered. Empirical treatment in the hospital or at home may be withheld if the infant has an excellent appearance and the complementary tests (leukocyte count, urine analysis and, if performed, the cerebrospinal fluid analysis) are all within normal range.

In children between three and 36 months, risk evaluation is usually more accurate (Figure 1). The medical approach should be based essentially on the physician’s judgement and the parents’ attitudes: a CBC, blood culture, and urine analysis and culture should not be mandatory.

CONCLUSIONS

There are no sufficiently reliable markers of bacterial infection. The physician must therefore practice medicine that is fraught with empiricism, but also based on sound scientific arguments and on his or her own personal experience. The child’s general appearance, temperature and leukocyte count are the best evaluation criteria. Practice guidelines never entirely compensate for a lack of clinical judgement.

Too often there is a tendency to rely immediately and excessively on complementary tests to reach a diagnosis on the cause of fever (72). It is often best to take the time to observe the child rather than hastily impose hospitalization, a multitude of tests and useless antibiotics.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the contribution of Dr Barbara Cummins-McManus for reviewing the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lee GM, Harper MB. Risk of bacteremia for febrile young children in the post-Haemophilus influenzae type b era. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1998;152:624–8. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.152.7.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belsey MA. Pneumococcal bacteremia. Am J Dis Child. 1967;113:588–9. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1967.02090200120015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Torphy DE, Ray CG. Occult pneumococcal bacteremia. Am J Dis Child. 1970;119:336–8. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1970.02100050338010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McGowan JE, Bratton L, Klein JO, Finland M. Bacteremia in febrile children seen in a “walk-in” pediatric clinic. N Engl J Med. 1973;288:1309–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197306212882501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rothrock SG, Harper MB, Green SM, et al. Do oral antibiotics prevent meningitis and serious bacterial infections in children with Streptococcus pneumoniae occult bacteremia? A meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 1997;99:438–44. doi: 10.1542/peds.99.3.438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Santé Canada, Comité consultatif national de l’immunisation . Vaccin contre Haemophilus. In: Guide canadien d’immunisation. Ottawa: Association médicale canadienne; 1998. pp. 110–5. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Santé Canada, Division de l’immunisation Rapport national sur l’immunisation au Canada, 1998. Paediatr Child Health. 1999;4(Suppl C):42C–77C. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Powell KR. Fever without a focus. In: Behrman RE, Kliegman RM, Jenson HB, editors. Nelson Texbook of Pediatrics. 16th edn. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2000. pp. 742–7. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuppermann N. Occult bacteremia in young febrile children. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1999;46:1073–109. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(05)70176-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kramer MS, Shapiro ED. Management of the young febrile child: A commentary on recent practice guidelines. Pediatrics. 1997;100:128–34. doi: 10.1542/peds.100.1.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Totapally BR, Walsh WT. Pneumococcal bacteremia in childhood. Chest. 1998;113:1207–14. doi: 10.1378/chest.113.5.1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laupland KB, Davies HD, Kellner JD, et al. Predictors and outcome of admission for invasive Streptococcus pneumoniae infections at a Canadian children’s hospital. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27:597–602. doi: 10.1086/514707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bradley JS, Kaplan SL, Tan TQ, et al. Pediatric pneumococcal bone and joint infections. The Pediatric Multicenter Pneumococcal Surveillance Study Group (PMPSSG) Pediatrics. 1998;102:1376–82. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.6.1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silverstein M, Bachur R, Harper MB. Clinical implications of penicillin and ceftriaxone resistance among children with pneumococcal bacteremia. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1998;18:35–41. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199901000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tan TQ, Mason EO, Barson WJ, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcome of children with pneumonia attributable to penicillin-susceptible and penicillin-nonsusceptible Streptococcus pneumoniae. Pediatrics. 1998;102:1369–75. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.6.1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dashefsky B, Teele DW, Klein JO. Unsuspected meningococcemia. J Pediatr. 1983;102:69–72. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(83)80290-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gottesman G, Israele V, Zierk-Diamond K, Salzman MB. Outcome of untreated meningococcal meningitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1996;15:1048–9. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199611000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sullivan TD, LaScolea LJ. Neisseria meningitidis bacteremia in children: Quantitation of bacteremia and spontaneous clinical recovery without antibiotic therapy. Pediatrics. 1987;80:63–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pollard AJ, DeMunter C, Nadel S, Levin M. Abandoning empirical antibiotics for febrile children. Lancet. 1997;350:811–2. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)62604-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baker MD. Evaluation and management of infants with fever. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1999;46:1061–72. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(05)70175-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Slater M, Krug SE. Evaluation of the infant with fever without source: An evidence based approach. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1999;17:97–126. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8627(05)70049-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kresh MJ. Axillary temperature as a screening test for fever in children. J Pediatr. 1984;104:596–9. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(84)80558-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baker MD, Avner JR, Bell LM. Failure of infant observation scales in detecting serious illness in febrile, 4- to 8-week-old infants. Pediatrics. 1990;85:1040–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alpert G, Hibbert E, Fleisher GR. Case-control study of hyperpyrexia in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1990;9:161–3. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199003000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Girodias JB, Payer P. Managing children with fever. Can J Pediatr. 1989 Sep;:4–8. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Surpure JS. Hyperpyrexia in children: Clinical implications. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1987;3:10–2. doi: 10.1097/00006565-198703000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bonadio WA, Grunske L, Smith DS. Systemic bacterial infections in children with fever greater than 41°C. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1989;8:120–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bonadio WA, Hegenbarth M, Zachariason M. Correlating reported fever in young infants with subsequent temperature patterns and rate of serious bacterial infections. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1990;9:158–60. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199003000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mazur LJ, Kozinetz CA. Diagnostic tests for occult bacteremia: Temperature response to acetaminophen versus WBC count. Am J Emerg Med. 1994;12:403–6. doi: 10.1016/0735-6757(94)90048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Teach SJ, Fleisher GR. Duration of fever and its relationship to bacteremia in febrile outpatients three to 36 months old. The Occult Bacteremia Study Group. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1997;13:317–9. doi: 10.1097/00006565-199710000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chamberlain JM, Gorman RL. Occult bacteremia in children with simple febrile seizures. Am J Dis Child. 1988;142:1073–6. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1988.02150100067028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Teach SJ, Geil PA. Incidence of bacteremia, urinary tract infections, and unsuspected bacterial meningitis in children with febrile seizures. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1999;15:9–12. doi: 10.1097/00006565-199902000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leach CT. Roseola (human herpes types 6 and 7) In: Behrman RE, Kliegman RM, Jenson HB, editors. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 16th edn. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2000. pp. 984–6. [Google Scholar]

- 34.McCarthy PL, Sharpe MR, Spiesel SZ, et al. Observation scales to identify serious illness in febrile children. Pediatrics. 1982;70:802–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jaskiewicz JA, McCarthy CA, Richardson AC, et al. Febrile infants at low risk for serious bacterial infection – An appraisal of the Rochester criteria and implications for management. Febrile Infant Collaborative Study Group. Pediatrics. 1994;94:390–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nicholson JF, Pesce MA. Reference ranges for laboratory tests and procedures. In: Behrman RE, Kliegman RM, Jenson HB, editors. Nelson textbook of Pediatrics. 16th edn. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2000. p. 2186. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stamos JK, Shulman ST. Abandoning empirical antibiotics for febrile children. Lancet. 1997;350:84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)61812-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mazur LJ, Kline MW, Lorin MI. Extreme leukocytosis in patients presenting to a pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1991;7:215–8. doi: 10.1097/00006565-199108000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Browne GJ, Ryan JM, McIntyre P. Evaluation of a protocol for empiric treatment of fever without localising signs. Arch Dis Child. 1997;76:129–33. doi: 10.1136/adc.76.2.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Isaacman DJ, Shults J, Gross TK, Davis PH, Harper M. Predictors of bacteremia in febrile children 3 to 36 months of age. Pediatrics. 2000;106:977–82. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.5.977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schelonka RL, Yoder BA. The WBC count and differential: Its uses and misuses. Contemporary Pediatr. 1996;13:124–41. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kuppermann N, Fleisher GR, Jaffe DM. Predictors of occult pneumococcal bacteremia in young febrile children. Ann Emerg Med. 1998;31:679–87. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(98)70225-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gendrel D, Raymond J, Coste J, et al. Comparison of procalcitonin with C-reactive protein, interleukin 6 and interferon-alpha for differentiation of bacterial versus viral infections. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1999;18:875–81. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199910000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hatherill M, Tibby SM, Sykes K, Turner C, Murdoch IA. Diagnostic markers of infection: Comparison of procalcitonin with C-reactive protein and leucocyte count. Arch Dis Child. 1999;81:417–21. doi: 10.1136/adc.81.5.417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Strait RT, Kelly KJ, Kurup VP. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-1 beta, and interleukin-6 levels in febrile, young children with and without occult bacteremia. Pediatrics. 1999;104:1321–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.104.6.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pulliam PN, Attia MW, Cronan KM. C-reactive protein in febrile children 1 to 36 months of age with clinically undetectable serious bacterial infection. Pediatrics. 2001;108:1275–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.6.1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lewin S, Dershewitz RA. Bacteremia. In: Dershewitz RA, editor. Ambulatory Pediatric Care. 3rd edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1999. pp. 957–61. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bachur R, Perry H, Harper MB. Occult pneumonias: Empiric chest radiographs in febrile children with leucocytosis. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;33:166–73. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(99)70390-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hoberman A, Chao HP, Keller DM, Hickey R, Davis HW, Ellis D. Prevalence of urinary tract infection in febrile infants. J Pediatr. 1993;123:17–23. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)81531-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Al-Orifi F, McGillivray D, Tange S, Kramer MS. Urine culture from bag specimens in young children: Are the risks too high? J Pediatr. 2000;137:221–6. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2000.107466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Baraff LJ, Schriger DL, Bass JW, et al. Management of the young febrile child. Commentary on practice guidelines. Pediatrics. 1997;100:134–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.100.1.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schriger DL. Management of the young febrile child. Clinical guidelines in the setting of incomplete evidence. Pediatrics. 1997;100:136. doi: 10.1542/peds.100.1.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Baraff LJ, Bass JW, Fleisher GR, et al. Practice guideline for the management of infants and children 0 to 36 months of age with fever without source. Ann Emerg Med. 1993;22:1198–210. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(05)80991-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jaffe DM, Tanz RR, Davis AT, Henretig F, Fleisher G. Antibiotic administration to treat possible occult bacteremia in febrile children. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:1175–80. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198711053171902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fleisher GR, Rosenberg N, Vinci R, et al. Intramuscular versus oral antibiotic therapy for the prevention of meningitis and other bacterial sequelae in young, febrile children at risk for occult bacteremia. J Pediatr. 1994;124:504–12. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)83126-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bauchner H, Pelton SI. Management of the young febrile child: A continuing controversy. Pediatrics. 1997;100:137–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.100.1.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Long SS. Antibiotic therapy in febrile children: “Best-laid schemes...”. J Pediatr. 1994;124:585–8. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)83137-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nelson JD, McCracken GHJ. One-liner of the month. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1991;17:8. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yamamoto LG. Revising the decision analysis for febrile children at risk for occult bacteriemia in a future era of widespread pneumococcal immunization. Clin Pediatr. 2001;40:583–94. doi: 10.1177/000992280104001101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Thuler LC, Jenicek M, Turgeon JP, Rivard M, Lebel P, Lebel MH. Impact of a false positive blood culture result on the management of febrile children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1997;16:846–51. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199709000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Baraff LJ, Bass JW, Fleisher GR, et al. Practice guideline for the management of infants and children 0 to 36 months of age with fever without source. Ann Emerg Med. 1993;22:1198–210. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(05)80991-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Letters to the editor. Practice guidelines for management of infants and children with fever without source. Pediatrics. 1994;93:344–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zerr DM, Del Beccaro MA, Cummings P. Predictors of physician compliance with a published guideline on management of febrile infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1999;18:232–8. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199903000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Baskin MN, O’Rourke EJ, Fleisher G. Outpatients treatment of febrile infants 28 to 89 days of age with intramuscular administration of ceftriaxone. J Pediatr. 1992;120:22–7. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)80591-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Baker MD, Bell LM, Avner JR. Outpatients management without antibiotics of fever in selected patients. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1437–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199311113292001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Baker MD, Bell LM, Avner JR. The efficacy of routine outpatient management without antibiotics of fever in selected infants. Pediatrics. 1999;103:627–31. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.3.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Baker MD, Avner JR. Management of fever in young infants. Clin Pediatr Emerg Med. 2000;1:102–8. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bachur RG, Harper MB. Predictive model for serious bacterial infections among infants younger than 3 months of age. Pediatrics. 2001;108:311–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.2.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bleeker SE, Moons KGM, Derksen-Lubsen G, Grobbee DE, Moll HA. Predicting serious bacterial infection in young children with fever without apparent source. Acta Paediatr. 2001;90:1226–32. doi: 10.1080/080352501317130236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Girodias JB, Chicoine L. Fièvre inexpliquée chez le jeune enfant: bactériémie ou virémie? Facteurs de risque et considérations pratiques. Le Clinicien. 1990;5:39–54. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Société canadienne de pédiatrie, Comité de maladies infectieuses et d’immunisation Approche thérapeutique de l’enfant de 1 à 36 mois souffrant de fièvre sans foyer d’infection. Paediatr Child Health. 1996;1:46–50. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Root RK, Petersdorf RG. Frissons de fièvre. In: Wilson JD, Braunwald E, Isselbacher KJ, et al., editors. Harrison Principes de Médecine Interne. 5e edn. Paris: Medecines-sciences Flammarion; 1992. pp. 125–33. [Google Scholar]