Abstract

In biological processes, such as fission, fusion and trafficking, it has been shown that lipids of different shapes are sorted into regions with different membrane curvatures. This lipid sorting has been hypothesized to be due to the coupling between the membrane curvature and the lipid's spontaneous curvature, which is related to the lipid's molecular shape. On the other hand, theoretical predictions and simulations suggest that the curvature preference of lipids, due to shape alone, is weaker than that observed in biological processes. To distinguish between these different views, we have directly measured the curvature preferences of several lipids by using a fluorescence-based method. We prepared small unilamellar vesicles of different sizes with a mixture of egg-PC and a small mole fraction of N-nitrobenzoxadiazole (NBD)-labeled phospholipids or lysophospholipids of different chain lengths and saturation, and measured the NBD equilibrium distribution across the bilayer. We observed that the transverse lipid distributions depended linearly on membrane curvature, allowing us to measure the curvature coupling coefficient. Our measurements are in quantitative agreement with predictions based on earlier measurements of the spontaneous curvatures of the corresponding nonfluorescent lipids using X-ray diffraction. We show that, though some lipids have high spontaneous curvatures, they nevertheless showed weak curvature preferences because of the low values of the lipid molecular areas. The weak curvature preference implies that the asymmetric lipid distributions found in biological membranes are not likely to be driven by the spontaneous curvature of the lipids, nor are lipids discriminating sensors of membrane curvature.

Keywords: curvature coupling, lipid spontaneous curvature, small unilamellar vesicle, fluorescence quenching

In biological membranes, lipids are not distributed homogeneously. The inhomogeneity of lipid distributions within a bilayer may be due to preferential association of particular lipid types with membrane proteins (1, 2), domain formation as a result of the interactions between lipids and sterols (3) or due to the preferences of lipids of different shapes toward regions of matching membrane curvature (4). Membrane regions in which the lipid inhomogeneity or sorting is observed are often highly curved. For example, (i) during mating in the protozoon Tetrahymena thermophila, the pore-containing membrane regions, which become highly negatively curved during fusion, are enriched in cone-shaped 2-aminoethylphosphonolipids (5); (ii) in Ca2+-dependent exocytosis and in regulated synaptic vesicle fusion, cone-shaped phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate lipids are important (6, 7), and are thought to facilitate the formation of an intermediate fusion structure by localizing at the fusion site (8); and (iii) lipids of different shapes are differently sorted in the tubules and vesicles in the endosomal pathway (9). These observations have raised the possibility that the distribution of the lipids may be determined by the coupling between membrane curvature and lipid shape.

Depending on the molecular shape, lipids form structures of different curvatures (10). The curvature of a monolayer composed of a single lipid species is determined by an intrinsic property of the lipids called spontaneous curvature (11). The spontaneous curvature of a lipid can be related heuristically to its shape: Cylindrical lipids form planer monolayers, and inverted-conical, and conical lipids form convex and concave monolayers, respectively (10). The cylindrical, inverted-conical, and conical lipids have zero, positive, and negative spontaneous curvatures, respectively (10). The mismatch between the lipid spontaneous curvature and the bilayer curvature introduces packing stress within the lipids (12). It has been hypothesized that in order to reduce the packing stress, the membrane changes its curvature and/or the lipids undergo lateral and transverse redistribution. Lipid spontaneous curvature is hypothesized to play a role in the membrane curvature preference of lipids (13–15).

The only known technique for measuring the spontaneous curvature of lipids relies on the formation of an inverted hexagonal (HII) phase of dioleoylphosphatidylethanolamine (DOPE) in aqueous solution. The periodicity of the HII structures in solutions of different osmotic pressures has been measured by X-ray diffraction and used to estimate both the spontaneous curvature and the bending stiffness of the DOPE lipids (16, 17). Not all lipids form the HII phase; however, the spontaneous curvature of some other lipids can be estimated by analyzing the perturbation in the periodicity of the DOPE HII phase caused by the addition of the second lipid type (17, 18). Theoretical studies based on these measurements (2, 19) and molecular-dynamic simulations (20, 21) suggested that the curvature preference of lipids is weaker than that observed in biological systems. Consistent with these studies, no significant sorting of lipids into membrane nanotubes was observed (22, 23).

To test these theoretical predictions and determine the relationship between the shape of a lipid and its preference to reside in a membrane leaflet of particular curvature, we directly measured the curvature preferences of several structurally different lipids using a fluorescence-based method. In this technique, trace quantities of fluorescently labeled lipids in small unilamellar vesicles (SUVs) of different mean diameters are studied at physiological temperature and salt concentration. The schematic diagrams of the lipids studied are shown in Fig. 1 and Fig. S1 (see SI Appendix). The N-nitrobenzoxadiazole (NBD)-labeled lipid transverse distribution is determined by a fluorescence quenching technique, from which we obtain the curvature coupling coefficient of the lipids.

Fig. 1.

The schematic diagram of the POPC, NBD-lyso-PPE, NBD-DPPE, NBD-lyso-OPE and NBD-DOPE lipids used in this study. POPC is the major component of egg-PC. The structures of NBD-lyso-MPE, NBD-DMPE, NBD-lyso-OPS and NBD-DOPS lipids are shown in Fig. S1 (see SI Appendix).

Model

Curvature-Dependent Transverse Lipid Distribution.

If we prepare small unilamellar vesicles (SUVs) with a mixture of egg-phosphatidylcholine (egg-PC) and a small mole fraction of NBD-labeled lipids, then the presence of the NBD-labeled lipids is not expected to affect the membrane properties, such as bending stiffness and membrane curvature. Rather, the membrane curvature may affect the transverse distribution of the NBD-labeled lipids (i.e., across the bilayer). The NBD-labeled lipids will prefer the leaflet that costs less energy. The bending energy cost per molecule for the NBD-labeled lipid to be in one of the leaflets is (11)

where H l is the mean curvature of the leaflet in which the NBD-labeled lipids are located, κ is the leaflet or monolayer bending stiffness and, c 0 and a are the mean spontaneous curvature and molecular area of the NBD-labeled lipids, respectively. The sign of c 0 depends on the shape of the NBD-labeled lipid. The bending stiffness, κ, is assumed equal in both of the bilayer leaflets. When the system is in equilibrium, the NBD-labeled lipids, along with the other lipids, translocate between the two leaflets and will prefer the leaflet that is energetically more favorable. According to Eq. 1, the energy cost per lipid for the NBD-labeled lipids being in the outer and inner leaflets are u o = 2κa(H o − c 0)2 and u i = 2κa(H i − c 0)2, respectively, where H o = 1/(R + D/2) and H i = −1/(R − D/2) are the mean curvatures of the outer and inner leaflets, assuming the SUVs are spherical, R is the radius of the SUV bilayer midplane, and D is the membrane bilayer thickness. Note that the outer leaflet is defined to have positive mean curvature (H o > 0) and, therefore, the inner leaflet has negative mean curvature (H i < 0). When the outer and inner leaflets have n o and n i fractions of NBD-labeled lipids, then the lipid densities are ρo = n o/A o and ρi = n i/A i where A o and A i are the outer and inner leaflet surface areas at the level of the headgroups. By using the Boltzmann distribution, we calculate the lipid density ratio as ρo/ρi = exp[−(u o − u i)/k B T]. Therefore, the ratio of the outer and inner leaflet NBD-labeled lipid fractions is

where k B is the Boltzmann constant and T is the temperature. Because the lipids are confined within the bilayer leaflets, we have n o + n i = 1. Therefore, by using Eq. 2, we can calculate n o as

|

Eq. 3 relates the NBD-labeled lipid transverse distribution function, n o, to the bilayer curvature, H (= 1/R), and the NBD-labeled lipid spontaneous curvature, c 0. For the NBD-labeled lipids with positive spontaneous curvature, the energy cost for being in the inner leaflet is higher than that for being in the outer leaflet (u i > u o); therefore, n o increases with the increasing bilayer curvature as the NBD-labeled lipids have preference for the outer leaflet of the bilayer. On the other hand, for negative spontaneous curvature NBD-labeled lipids, n o decreases with increasing bilayer curvature as u o > u i, meaning that the NBD-labeled lipids have preference for the inner leaflet of the bilayer.

When the membrane bilayer is flat or the lipid spontaneous curvature is very small, the energy cost for the NBD-labeled lipids being in either of the leaflets is almost equal (u o ≈ u i). In both cases, the NBD-labeled lipids are symmetrically distributed in the two leaflets, and Eq. 3 becomes

where A is the total area of the two leaflets. Therefore, the symmetric distribution function, n s, is the frame of reference with respect to which we can estimate the asymmetric transverse distribution of the NBD-labeled lipids in the bilayer leaflets.

Curvature Coupling Coefficient.

In biological vesicle systems such as synaptic vesicles or the vesicles in the endosomal pathway, the typical membrane curvature ranges from 0.005 nm−1 to 0.05 nm−1 (corresponding to diameters from 400 to 40 nm). In this curvature range, n o (Eq. 3) is approximately proportional to membrane curvature because, as we show, ≈constant. Therefore, the Taylor expansion of Eq. 3 around zero mean curvature

where

is a good approximation for the lipid distribution. The first term in Eq. 5, (1 + DH)/2, expresses the symmetric distribution of the NBD-labeled lipids in a bilayer of curvature H and is equivalent to Eq. 4 for R ≫ D/2, a valid approximation in our range of bilayer curvatures. The second term, ΓH, is the measure of fractional lipid asymmetry due to the curvature preference of the NBD-labeled lipids. For Γ > 0, the NBD-labeled lipids prefer the outer leaflet and for Γ < 0, the lipids prefer the inner leaflet. As Γ encapsulates all the necessary mechanical parameters, including c 0, that may contribute to the curvature dependent asymmetric transverse distribution of the lipid of interest, we call Γ the curvature coupling coefficient.

Finally, in order to calculate the values of Γ and c 0 from the experimental measurements of the transverse distribution, n o, we have used literature values of the parameters κ, D and a in Eq. 5 (see Relationship Between Curvature Coupling Coefficient and Spontaneous Curvature).

Results

Properties of the SUVs.

We have prepared the SUVs of different sizes and lipid compositions by using the protocol described in the Materials and Methods section. The SUV size distributions were measured by dynamic light scattering (DLS) (Zetasizer Nano ZS). The DLS data (scattered light intensity vs. hydrodynamic diameter) were converted to SUV number (%) vs. hydrodynamic diameter (Fig. 2 A) using the nonnegatively constrained least squared (NNLS) fitting algorithm included in the CONTIN regularization package (24). The mean diameter and standard deviation of the SUVs (Table 1) were estimated by fitting the data with the log-normal distribution function. We did not detect any micelles by DLS, showing that the lyso lipids incorporated into the SUVs.

Fig. 2.

Sizes of the SUVs. (A) The size distribution of SUVs extruded through polycarbonate membrane filters with the indicated pore sizes measured by dynamic light scattering (DLS). Mean diameters and standard deviations measured by fitting with the log-normal distribution function are shown in Table 1. (B) Cryo-TEM images of egg-PC + NBD-lyso-PPE SUVs of different size distributions. The images were taken about 24 hours after preparation. SUVs are of mean diameter (i) 31 ± 13 nm, (ii) 50 ± 18 nm, (iii) 70 ± 21 nm and (iv) 83 ± 25 nm (Table 1). Unilamellar, bilamellar, and trilamellar vesicles are marked with single, double, and triple arrowheads, respectively.

Table 1.

The diameters of the SUVs prepared by extrusion through polycarbonate membranes with the indicated pore sizes measured by using DLS and cryo-TEM data

| Pore size, nm | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vesicle property | 15 | 30 | 80 | 100 |

| Mean diameter, nm, DLS | 36 ± 7 | 46 ± 9 | 67 ± 14 | 83 ± 17 |

| Mean diameter, nm, cryo-TEM | 31 ± 13 | 50 ± 18 | 70 ± 21 | 83 ± 25 |

| Second bilayer fraction, fb(%) | 0 | 8 | 11 | 14 |

| Third bilayer fraction, ft(%) | 0 | 2 | 0.6 | 0.8 |

| Second bilayer mean diameter, nm | — | 31 | 46 | 52 |

| Third bilayer mean diameter, nm | — | 26 | 31 | 37 |

The fractional amount of the second and third bilayers, and their respective mean diameters in the MLVs, were estimated by analyzing 200 vesicles from three independently prepared samples from the cryo-TEM images of each size category. The errors are standard deviations.

The presence of multilamellar vesicles (MLVs), which cannot be ascertained by DLS, can potentially confound our quenching technique. We therefore used cryotransmission electron microscopy (cryo-TEM) to obtain images of unstained SUVs of different size distributions in order to estimate the fractional number of MLVs present in the samples (Fig. 2 B). The cryo-TEM images show that there are small fractions of bilamellar and trilamellar MLVs in all but the 36-nm-diameter SUV distributions. We did not observe MLVs with more than three bilayers. The MLVs containing two smaller SUVs, not necessarily concentric, are considered trilamellar. The fractional amount of the second and third MLV bilayers present in the distribution and their mean diameters obtained by analyzing 200 vesicles from three separate sample preparations of each size category are summarized in Table 1. The mean diameters of the SUV distributions measured by DLS and cryo-TEM were consistent with each other; because the cryo-TEM measurements have larger standard deviation due to the smaller number of samples, we used the SUV size-distribution data in our calculations.

Measurement of the NBD-Labeled Lipid Transverse Distribution.

The fractional transverse distributions of the NBD-labeled lipids across the SUV bilayers were measured by quenching the NBD-labeled lipids in the outer leaflet of the SUVs with sodium dithionite (SDT), Na2S2O4 (25). SDT undergoes an irreversible reduction reaction with the NBD and makes NBD nonfluorescent. Furthermore, SDT has very low permeability through the membrane bilayer (25, 26). Prior to these measurements, the SUVs were diluted 10-fold in NaCl-HEPES buffer and incubated for 14 to 16 hours at 37°C to allow the NBD-labeled lipids to equilibrate across the bilayer (confirmed by the quenching measurements). Fluorescence of the SUVs was measured by using a fluorometer (FluoroMax-3, HORIBA Jobin Yvon Inc). The signal-to-noise ratio was always maintained around 20. Because lipid distribution in the bilayer is affected by the pH gradient across the membrane (27), pH 7.4 was maintained inside and outside the SUVs. In order to measure the lipid distribution of the NBD-labeled lipids, we first measured the total fluorescence of a 1-mL solution of SUVs for about 200 seconds and then added 15 mM SDT prepared in 1 M Trizma base (pH 10). We observed a fast decrease in fluorescence due to the irreversible reduction reaction of the SDT with the NBD-labeled lipids in the outer leaflet followed by a very slow fluorescence decrease due to the outward translocation of the inner leaflet NBD-labeled lipids (Fig. 3 A). The NBD-SDT reaction rate is much higher than the SDT membrane permeation, NBD-dipalmitoylphosphatidylethanolamine (NBD-DPPE) translocation, and photo bleaching rates (26). When we dissolved the SUVs with detergent, 20 mM Triton X100, we observed another fast drop in the fluorescence to zero due to the exposure of the remaining inner leaflet NBD-labeled lipids to the SDT, which is still abundant in the buffer (Fig. 3 A). This observation demonstrates that the initial fluorescence drop gives us a good estimation of the mean fraction of the NBD-labeled lipid distribution in the outer leaflets of the SUV ensemble.

Fig. 3.

Fluorescent-quenching method for estimating the fractional outer leaflet NBD-labeled lipid distribution in the SUVs. (A) SUVs of 83 nm mean diameter were prepared from egg-PC with a small mole fraction (0.01%) of NBD-DPPE. Addition of 15 mM SDT caused a fast decrease in total fluorescence due to NBD quenching. The following slow decrease is mainly due to outward translocation of inner leaflet NBD-DPPE lipids. Addition of 20 mM detergent, Triton-X100, dissolves the membrane, exposing the rest of the NBD-DPPE lipids in the inner leaflet to SDT, causing the total fluorescence to drop to zero. Data were normalized after background subtraction. (B) Fluorescence quenching of the SUV outer leaflet NBD-lyso-PPE (Left) and NBD-DPPE (Right) lipids by SDT. The fast drop in fluorescence, I o, represents the fractional amount of NBD-lyso-PPE or NBD-DPPE present in the outer leaflet of the SUVs. In case of NBD-lyso-PPE, I o increases with decreasing SUV diameter. The opposite effect is observed for NBD-DPPE lipids.

Fig. 3 B shows measurements of the outer leaflet NBD-DPPE and NBD-palmitoylphosphatidylethanolamine (NBD-lyso-PPE) lipid fractions in different SUV size distributions. The fluorescent intensity data were normalized after background subtraction. For the 36-nm SUVs, there were no MLVs present in the SUV distribution, so the rapid fractional drop in intensity, I o, is a measure of the average fraction of NBD-labeled lipids distributed in the outer leaflets of the SUVs. For the other SUVs, there was a small contamination with MLVs (Table 1); I o was therefore corrected for these MLVs to obtain n o (see SI Appendix for details).

Curvature Preference of Lipids and the Curvature Coupling Coefficient.

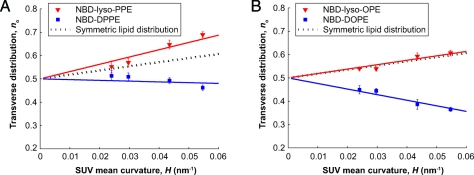

We measured the transverse distribution, n o, for all the NBD-labeled lipids (Fig. 4 and Fig. S2 of the SI Appendix). In all the measurements, the transverse distribution of the NBD-labeled lipids was approximately proportional to the SUV membrane curvature, in agreement with Eq. 5. The saturated lyso lipids, NBD-myristoylphosphatidylethanolamine (NBD-lyso-MPE) NBD-lyso-PPE and showed increasing preference for the positive curvature outer leaflet with the increase in SUV membrane curvature (Fig. 4 A and Fig. S2A of the SI Appendix). On the other hand, the saturated NBD-dimyristoylphosphatidylethanolamine (NBD-DMPE) NBD-DPPE and lipids showed decreasing preference for the outer leaflet with increasing bilayer curvature, which implies that these lipids have preference for the inner leaflet of the bilayer. The unsaturated NBD-DOPE and NBD-dioleoylphosphatidylserine (NBD-DOPS) lipids showed curvature-dependent asymmetric distribution toward the inner leaflets (Fig. 4 B and Fig. S2B of the SI Appendix). Taking the symmetric lipid-distribution function, n s (Eq. 4), as the frame of reference, the saturated lyso lipids, NBD-lyso-MPE and NBD-lyso-PPE, show ≈10% enrichment in the outer leaflet, and the saturated NBD-DMPE and NBD-DPPE lipids show ≈15% enrichment in the inner leaflet of the SUVs with mean curvature 0.056 nm−1 (36-nm diameter). For the same SUV curvature, both the unsaturated NBD-DOPE and NBD-DOPS lipids showed ≈24% enrichment in the inner leaflet, whereas the NBD-oleoylphosphatidylethanolamin (NBD-lyso-OPE) and NBD-oleoylphosphatidylserine (NBD-lyso-OPS) lipids did not show any significant preference for either of the leaflets, as indicated by the overlap of the transverse distribution data points with the line corresponding to n s.

Fig. 4.

The transverse distribution, n o, of the NBD-labeled lipids as a function of SUV bilayer curvature, H. The dotted lines correspond to symmetric distribution, n s (Eq. 4). (A) The NBD-lyso-PPE (▾) lipids show preference for the positive curvature outer leaflet, whereas the NBD-DPPE (▪) lipids show preference for the inner leaflet. (B) The unsaturated NBD-lyso-OPE (▾) lipids do not show any significant preference for any of the leaflets as it overlaps with n s. The unsaturated NBD-DOPE (▪) lipids prefer the negative curvature inner leaflet. By fitting the data with Eq. 5 (the red and blue lines for the single- and double-chain lipids, respectively) we estimated the curvature coupling coefficient, Γ, and spontaneous curvature, c 0, of the lipids (Table 2).

The curvature coupling coefficient, Γ, was estimated (Table 2) by fitting Eq. 5 with the n o vs. H data (Fig. 4 and Fig. S2 of the SI Appendix) by chi-squared minimization weighted by the standard deviations along both of the axes. Thus, the smaller SUVs with narrower size distributions give slightly more weight to the fitting.

Table 2.

The curvature coupling, Γ, and spontaneous curvature, c 0, of the NBD-labeled lipids in egg-PC membranes

| Lipid | Γ, nm | a, Å2 | c0, nm−1 | r0 = c0−1, nm |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NBD-DMPE | −2.65 ± 0.13 | 43 | −0.31 | −3.3 |

| NBD-DPPE | −2.13 ± 0.13 | 48 | −0.22 | −4.5 |

| NBD-DOPE | −4.19 ± 0.10 | 68 | −0.31 | −3.2 |

| NBD-DOPS | −5.49 ± 0.20 | 66 | −0.42 | −2.4 |

| NBD-lyso-MPE | 1.67 ± 0.13 | 31 | 0.27 | 3.7 |

| NBD-lyso-PPE | 1.32 ± 0.15 | 38 | 0.17 | 5.8 |

| NBD-lyso-OPE | 0.10 ± 0.08 | 47 | 0.01 | |r0| ≥ 55 |

| NBD-lyso-OPS | −0.08 ± 0.16 | 48 | −0.01 | |r0| ≥ 40 |

The values of Γ are obtained by fitting Eq. 5 with the NBD-labeled lipid transverse distribution data (Fig. 4 and Fig. S2 of the SI Appendix). The c 0 values are calculated using Eq. 6. There are about 90 data points per lipid category. The errors are 95% confidence limits.

Relationship Between Curvature Coupling Coefficient and Spontaneous Curvature.

To relate the curvature coupling coefficient, Γ, to the spontaneous curvature, c 0, via Eq. 6, we used the following parameter values for the different NBD-labeled lipids from the literature (where possible). The bending stiffness of a lipid monolayer has the same order of magnitude for different lipids and has been estimated as κ = 10 k B T (κ range, 9–11 k B T) (28–30). The thickness of the egg-PC SUV membrane bilayer, D, is 3.6 nm (31, 32). The NBD fluorophore is attached to the head group of the phosphatidylcholine (PE) and phosphatidylserine (PS) lipids, and the NBD is outside the membrane surface (33); because only a very small proportion of the lipids in the SUVs are labeled with NBD, we assumed that there is no interaction between the NBD-labeled head groups. Therefore, the NBD molecules do not contribute to the molecular area, a, of the attached lipids. The molecular area of the DMPE is 43 Å2 (34), DPPE is 48 Å2 (35), DOPE is 68 Å2 (36), DOPS is 66 Å2 (37), lyso-MPE is 31 Å2 and lyso-PPE is 38 Å2 (38). We measured the areas of lyso-OPE and lyso-OPS to be 47 Å2 and 48 Å2, respectively (see Fig. S3 of the SI Appendix). The uncertainty of the calculated values of c 0 depends on the measurement errors in Γ as well as on the uncertainties in a and κ. The value of κ has a large relative uncertainty: The standard deviation divided by the mean is about 10%. The relative uncertainties in a are small (<5%) and those in Γ are ≈5% except for NDB-lyso-OPE and NBD-lyso-OPS. Therefore, the relative uncertainties of our calculated c 0 values are approximately equal to that of κ except for the cases of the unsaturated lyso lipids.

Discussion

The strength of the curvature preferences of the trace amounts of the NBD-labeled lipids in the egg-PC membrane are quantified by the curvature coupling coefficient, Γ (Table 2). The unsaturated NBD-DOPE and NBD-DOPS lipids show comparatively higher preference for the inner leaflet with Γ values −4.2 nm and −5.5 nm, respectively. The small Γ values of the NBD-lyso-OPE and NBD-lyso-OPS lipids (0.01 nm and −0.08 nm, respectively) imply that these lipids do not display curvature-dependent asymmetric transverse distributions. The saturated NBD-DMPE, NBD-DPPE, NBD-lyso-MPE, and NBD-lyso-PPE lipids, with respective Γ values −2.7, −2.1, 1.7, and 1.3 nm, have a higher preference for the outer leaflet compared with the corresponding unsaturated NBD-labeled lipids.

Knowing the Γ value of a lipid, one can readily estimate the fractional curvature preference of the lipid for a given SUV size by using Eq. 5. For example, by using the value Γ = −4.2 nm for NBD-DOPE, we can estimate that ≈4.2% and ≈21% NBD-DOPE lipids would be enriched in the negative curvature inner leaflet of the SUVs of mean curvature 0.01 nm−1 and 0.05 nm−1, respectively. From Table 2, the curvature preference of all the NBD-labeled lipids would become very low (<10%) in SUVs with a diameter larger than 100 nm. These observations support predictions of coarse-grained molecular-dynamic simulations in SUVs (20, 21) and theoretical studies (2, 19).

Our measurements of the curvature coupling coefficient allow us to estimate the spontaneous curvatures (Table 2). The saturated lyso lipids, NBD-lyso-MPE and NBD-lyso-PPE, are inverted-conical lipids (c 0 > 0) and all the double-chain NBD-labeled lipids are conical lipids (c 0 < 0). The unsaturated lyso lipids, NBD-lyso-OPE and NBD-lyso-OPS, are approximately cylindrical as they have very low spontaneous curvature values.

In the X-ray diffraction measurement of the HII phase at pH 7.0, the spontaneous radius of curvature of the DOPE and lyso-OPE lipids were measured to be ≈−3 nm and larger than 40 nm, respectively (17, 30). Our inferred values of spontaneous curvatures are in good agreement with these X-ray diffraction measurements: The spontaneous radius of curvature, r 0 (= 1/c 0), of NBD-DOPE and NBD-lyso-OPE lipids are −3.2 nm and r 0 ≥ 55 nm (estimated from the standard error), respectively. Our r 0 value (−2.4 nm) for NBD-DOPS at pH 7.4 differs from the X-ray diffraction measurements for DOPS [14.4 nm at pH 7.0 (18)]. However, the concentration of negatively charged DOPS in the X-ray assay is much higher than that in our assay, and the mutual repulsion between the negatively charged DOPS lipids is expected to make the spontaneous radius of curvature positive. Neutralizing the DOPS charge at pH 2.0 in the X-ray experiments decreased the spontaneous radius of curvature to - 2.3 nm (18). As we are using a very small fraction of NBD-DOPS, the effect of coulomb repulsion between the NBD-DOPS is negligible and, hence, we regard our measured r 0 (−2.4 nm at pH 7.4) in close agreement with the X-ray diffraction measurements at low pH. In addition, we estimated that the r 0 values of NBD-DMPE, NBD-DPPE, and NBD-lyso-MPE are −3.3 nm, −4.5 nm, and 3.7 nm, respectively. The r 0 value of NBD-lyso-OPS is estimated, from the standard error of the measurements, to be |r 0| ≥ 40 nm.

According to the derivation of Γ (Eq. 6), the curvature preference of a lipid depends linearly on the lipid spontaneous curvature, c 0, as well as on the monolayer bending stiffness, κ, and lipid molecular area, a. Higher bending stiffness as well as larger molecular area promotes curvature preference of lipids. According to our estimation, despite the similar c 0 values of NBD-DMPE and NBD-DOPE lipids, NBD-DOPE lipids have ≈1.6 times higher curvature preference than that of NBD-DMPE lipids because of the larger molecular area of the NBD-DOPE lipids. For the same reason, the NBD-DMPE lipids have higher curvature preference than the NBD-lyso-MPE lipids, although their spontaneous curvature values are almost equal in magnitude. Therefore, in the cases of larger molecules such as cardiolipin, monosialotetrahexosylganglioside (GM1), transmembrane proteins and peptides, we predict stronger curvature preference because of the larger molecular areas. Also, lipid cluster formation, assisted by sterols or proteins, resulting in a larger area of molecular assembly, could promote stronger curvature preference of lipids. It has been shown that in periodically curved supported bilayer systems, lipid clusters tend to phase separate where the clusters localize in the low membrane curvature region (39). In vesicle–nanotube systems, protein-assisted lipid clusters tend to stay out of the high curvature membrane nanotube region (22, 23). In both cases, in the absence of lipid clustering, the lipids did not show any lateral curvature preference. In the absence of clustering, curvature-dependent lipid sorting was shown to occur only near the demixing point of lipid–sterol mixtures (22). Phase separation and proximity to a demixing point can lead to amplified sensitivity to curvature gradients in various ways (40, 41). These observations can be understood by noting that individual lipids, in general, have very small molecular area compared with transmembrane proteins, peptides, lipid clusters, or heterogeneity of lipids near demixing point. Thus, our observations suggest that, although some lipids have high spontaneous curvatures, the membrane curvature preferences of these lipids is weak because of the small molecular area of the lipids.

In a recently published work, a fivefold relative sorting of two lipid types into membrane tubes with diameters of ≈70 nm was reported (42). These observations contradict other observations (22, 23) as well as our own work (see SI Appendix). Furthermore, our calculation shows that a fivefold lipid sorting is not realistic based on the curvature preference alone (see SI Appendix). Thus, other explanations are required to account for these data.

Let us now compare our observations with some biological membrane systems containing PE and PS lipids, which are mainly unsaturated. In erythrocytes (diameter 8 μm), ≈80% of the PE and 95% of the PS lipids are distributed in the inner leaflet (27). According to Eq. 5, both the PE and PS lipids should be equally distributed in the bilayer leaflets as the membrane curvature of erythrocyte is very small [<0.001 nm−1 (43)]. Therefore, factors other than membrane curvature—such as lipid flippases—must be driving the lipid asymmetry (27). In the case of synaptic vesicles (diameter 40–100 nm), 40–50% of PE and ≈60% of the PS lipids are distributed in the inner leaflet (44, 45). According to our measurements, both NBD-DOPE and NBD-DOPS lipids asymmetrically distributed with ≈60% NBD-DOPE and 65% NBD-DOPS lipids in the inner leaflet of the SUVs in the similar diameter range (36–83 nm). Although the asymmetric distribution of the PS lipids in synaptic vesicles is similar to that of the NBD-DOPS lipids in the SUVs of similar size range, the PE lipids in the synaptic vesicles show a different trend than the NBD-DOPE lipids in the SUVs. Thus, in biological systems the curvature preference of the lipids must be influenced by factors other than a spontaneous curvature.

In this work, we measured the curvature coupling coefficient of NBD-labeled lipids in SUVs composed of a natural lipid mixture, egg-PC, in physiological conditions. Our observations suggest that the coupling between membrane curvature and lipid shape is weak mainly because of small molecular area of the lipids. This implies that the asymmetric lipid distributions within the biological membranes are not likely to be driven by the spontaneous curvature of the lipids, nor are lipids discriminating sensors of membrane curvature.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of the SUVs.

We first prepared lipid films from 104:1 (mol:mol) mixture of egg-PC (99% pure from chicken egg, product ID: 840051, Avanti polar lipids) and one of the NBD headgroup-labeled phospholipid derivatives NBD-DMPE, NBD-lyso-MPE, NBD-DPPE, NBD-lyso-PPE, NBD-DOPE, NBD-lyso-OPE, NBD-DOPS, and NBD-lyso-OPS (Fig. 1 and Fig. S1). The major component of egg-PC lipid mixture is (POPC) 1-palmitory-2-olely-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (Fig. 1). The lipid films were made by drying the lipid mixture, which was desolved in chloroform-methanol (2:1). The concentration of the lipid mixture was 1 mg/mL. The lipid films were kept in a vacuum oven for 4 hours at 45°C, well above the melting point (−5°C) of the lipid mixture, then rehydrated with NaCl-HEPES buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM HEPES, 0.2 mM EDTA, pH 7.4) for 2 hours with ≈2 Hz agitation at 45°C. Rehydration causes formation of MLVs of different diameters. SUVs of different diameter distributions were prepared by extrusion of the MLVs with 50 passes through polycarbonate membrane filters of pore sizes 15 nm, 30 nm, 80 nm, and 100 nm (Whatman). Prior to extrusion, we applied the freeze-thaw technique to assure that the extruded SUVs were mostly unilamellar.

The double-chain NBD-labeled lipids were purchased from Avanti polar lipid. The NBD-labeled lyso lipids were prepared by phospholypase A2 hydrolysis of the NBD-labeled double-chain lipids and separated by thin-layer chromatography to have single chain NBD-lyso-MPE, NBD-lyso-PPE, NBD-lyso-OPE and NBD-lyso-OPS. The quality of the prepared NBD-labeled lipids was checked by mass spectrometry. The molecular areas of the nonfluorescent lyso-OPE and lyso-OPS lipids were measured using a Langmuir–Blodgett trough as shown in Fig. S3 of the SI Appendix, and the molecular areas of other nonfluorescent lipids were taken from the literature.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

The authors would like to thank Kai Simons, Sol M. Gruner, and the Howard lab members for their helpful comments on the manuscript. M.M.K. would like to thank Werner Kühlbrandt for the suggestions and support regarding the cryo-TEM imaging, Christoph Thiele, Jacques Pecreaux, and Ünal Coskun for helpful discussions, and Julio Sampaio for his help with the quality control of the lipids using mass spectrometry.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0907354106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Dumas F, Sperotto MM, Lebrun MC, Tocanne JF, Mouritsen OG. Molecular sorting of lipids by bacteriorhodopsin in dilauroylphosphatidylcholine/distearoylphosphatidylcholine lipid bilayers. Biophys J. 1997;73:1940–1953. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78225-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zimmerberg J, Kozlov MM. How proteins produce cellular membrane curvature. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:9–19. doi: 10.1038/nrm1784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huttner WB, Zimmerberg J. Implications of lipid microdomains for membrane curvature, budding and fission. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2001;13:478–484. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00239-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McMahon HT, Gallop JL. Membrane curvature and mechanisms of dynamic cell membrane remodelling. Nature. 2005;438:590–596. doi: 10.1038/nature04396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ostrowski SG, Van Bell CT, Winograd N, Ewing AG. Mass spectrometric imaging of highly curved membranes during Tetrahymena mating. Science. 2004;305:71–73. doi: 10.1126/science.1099791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muller M, Zschornig O, Ohki S, Arnold K. Fusion, leakage and surface hydrophobicity of vesicles containing phosphoinositides: Influence of steric and electrostatic effects. J Membr Biol. 2003;192:33–43. doi: 10.1007/s00232-002-1062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Di Paolo G, et al. Impaired PtdIns(4,5)P2 synthesis in nerve terminals produces defects in synaptic vesicle trafficking. Nature. 2004;431:415–422. doi: 10.1038/nature02896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salaun C, James DJ, Chamberlain LH. Lipid rafts and the regulation of exocytosis. Traffic. 2004;5:255–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2004.0162.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mukherjee S, Soe TT, Maxfield FR. Endocytic sorting of lipid analogues differing solely in the chemistry of their hydrophobic tails. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:1271–1284. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.6.1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Israelachvili J. Intermolecular & Surface Forces. 2nd Ed. London: Academic; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Helfrich W. Elastic properties of lipid bilayers: Theory and possible experiments. Z Naturforsch C. 1973;28:693–703. doi: 10.1515/znc-1973-11-1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gruner SM. Stability of lyotropic phases with curved interfaces. J Phys Chem. 1989;93:7562–7570. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leibler S. Curvature instability in membranes. J Physique. 1986;47:507–516. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seifert U. Curvature-induced lateral phase segregation in two-component vesicles. Phys Rev Lett. 1993;70:1335–1338. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.70.1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carnie S, Israelachvili JN, Pailthorpe BA. Lipid packing and transbilayer asymmetries of mixed lipid vesicles. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1979;554:340–357. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(79)90375-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rand RP, Fuller NL, Gruner SM, Parsegian VA. Membrane curvature, lipid segregation, and structural transitions for phospholipids under dual-solvent stress. Biochemistry. 1990;29:76–87. doi: 10.1021/bi00453a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fuller N, Rand RP. The influence of lysolipids on the spontaneous curvature and bending elasticity of phospholipid membranes. Biophys J. 2001;81:243–254. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75695-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fuller N, Benatti CR, Rand RP. Curvature and bending constants for phosphatidylserine-containing membranes. Biophys J. 2003;85:1667–1674. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(03)74596-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Derganc J. Curvature-driven lateral segregation of membrane constituents in Golgi cisternae. Phys Biol. 2007;4:317–324. doi: 10.1088/1478-3975/4/4/008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cooke IR, Deserno M. Coupling between lipid shape and membrane curvature. Biophys J. 2006;91:487–495. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.078683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Risselada HJ, Marrink SJ. Curvature effects on lipid packing and dynamics in liposomes revealed by coarse grained molecular dynamics simulations. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2009;11:2056–2067. doi: 10.1039/b818782g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sorre B, et al. Curvature-driven lipid sorting needs proximity to a demixing point and is aided by proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:5622–5626. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811243106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tian A, Baumgart T. Sorting of lipids and proteins in membrane curvature gradients. Biophys J. 2009;96:2676–2688. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.11.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Provencher SW. CONTIN—A general-purpose constrained regularization program for inverting noisy linear algebraic and integral-equations. Comput Phys Commun. 1982;27:229–242. [Google Scholar]

- 25.McIntyre JC, Sleight RG. Fluorescence assay for phospholipid membrane asymmetry. Biochemistry. 1991;30:11819–11827. doi: 10.1021/bi00115a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moreno MJ, Estronca LM, Vaz WL. Translocation of phospholipids and dithionite permeability in liquid-ordered and liquid-disordered membranes. Biophys J. 2006;91:873–881. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.082115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Devaux PF. Static and dynamic lipid asymmetry in cell membranes. Biochemistry. 1991;30:1163–1173. doi: 10.1021/bi00219a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Niggemann G, Kummrow M, Helfrich W. The bending rigidity of phosphatidylcholine bilayers—Dependences on experimental-method, sample cell Sealing and temperature. J Physique II. 1995;5:413–425. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen Z, Rand RP. The influence of cholesterol on phospholipid membrane curvature and bending elasticity. Biophys J. 1997;73:267–276. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78067-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leikin S, Kozlov MM, Fuller NL, Rand RP. Measured effects of diacylglycerol on structural and elastic properties of phospholipid membranes. Biophys J. 1996;71:2623–2632. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79454-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilkins MH, Blaurock AE, Engelman DM. Bilayer structure in membranes. Nat New Biol. 1971;230:72–76. doi: 10.1038/newbio230072a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tristram–Nagle S, Nagle JF. Lipid bilayers: Thermodynamics, structure, fluctuations, and interactions. Chem Phys Lipids. 2004;127:3–14. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abrams FS, London E. Extension of the parallax analysis of membrane penetration depth to the polar region of model membranes: Use of fluorescence quenching by a spin-label attached to the phospholipid polar headgroup. Biochemistry. 1993;32:10826–10831. doi: 10.1021/bi00091a038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Graf K, Riegler H. Molecular adhesion interactions between Langmuir monolayers and solid substrates. Colloids Surfaces A. 1998;131:215–224. [Google Scholar]

- 35.McQuaw CM, Sostarecz AG, Zheng L, Ewing AG, Winograd N. Lateral heterogeneity of dipalmitoylphosphatidylethanolamine-cholesterol Langmuir–Blodgett films investigated with imaging time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry and atomic force microscopy. Langmuir. 2005;21:807–813. doi: 10.1021/la0479455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dufrene YF, Barger WR, Green JBD, Lee GU. Nanometer-scale surface properties of mixed phospholipid monolayers and bilayers. Langmuir. 1997;13:4779–4784. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Petrache HI, et al. Structure and fluctuations of charged phosphatidylserine bilayers in the absence of salt. Biophys J. 2004;86:1574–1586. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74225-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yamanaka T, Ogihara N, Ohhori T, Hayashi H, Muramatsu T. Surface chemical properties of homologs and analogs of lysophosphatidylcholine and lysophosphatidylethanolamine in water. Chem Phys Lipids. 1997;90:97–107. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parthasarathy R, Yu CH, Groves JT. Curvature-modulated phase separation in lipid bilayer membranes. Langmuir. 2006;22:5095–5099. doi: 10.1021/la060390o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Groves JT, Boxer SG, McConnell HM. Electric field-induced critical demixing in lipid bilayer membranes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:935–938. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.3.935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Veatch SL, et al. Critical fluctuations in plasma membrane vesicles. Am Chem Soc Chem Biol. 2008;3:287–293. doi: 10.1021/cb800012x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hatzakis NS, et al. How curved membranes recruit amphipathic helices and protein anchoring motifs. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:835–841. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Khairy K, Foo J, Howard J. Shapes of red blood cells: Comparison of 3D confocal images with the bilayer-couple model. Cell Mol Bioeng. 2008;1:173–181. doi: 10.1007/s12195-008-0019-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Deutsch JW, Kelly RB. Lipids of synaptic vesicles: Relevance to the mechanism of membrane fusion. Biochemistry. 1981;20:378–385. doi: 10.1021/bi00505a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Michaelson DM, Barkai G, Barenholz Y. Asymmetry of lipid organization in cholinergic synaptic vesicle membranes. Biochem J. 1983;211:155–162. doi: 10.1042/bj2110155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.