Abstract

Objectives

The severity of acute carbon monoxide (CO) poisoning is often based on non-specific clinical criteria because there are no reliable laboratory markers. We hypothesized that a pattern of plasma protein values might objectively discern CO poisoning severity. This was a pilot study to evaluate protein profiles in plasma samples collected from patients at the time of initial hospital evaluation. The goal was to assess whether any values differed from age- and sex-matched controls using a commercially available plasma screening package.

Methods

Frozen samples from 63 suspected CO poisoning patients categorized based on clinical signs, symptoms, and blood carboxyhemoglobin level were analyzed along with 42 age- and sex-matched controls using Luminex-based technology to determine the concentration of 180 proteins.

Results

Significant differences from control values were found for 99 proteins in at least one of five CO poisoning groups. A complex pattern of elevations in acute phase reactants and proteins associated with inflammatory responses including chemokines/cytokines and interleukins, growth factors, hormones, and an array of auto-antibodies was found. Fourteen protein values were significantly different from control in all CO groups, including patients with nominal carboxyhemoglobin elevations and relatively brief intervals of exposure.

Conclusions

The data demonstrate the complexity of CO pathophysiology and support a view that exposure causes acute inflammatory events in humans. This pilot study has insufficient power to discern reliable differences among patients who develop neurological sequelae but future trials are warranted to determine whether plasma profiles predict mortality and morbidity risks of CO poisoning.

Keywords: Inflammatory markers, Smoke inhalation, Hyperbaric oxygen, Cytokines

Introduction

Carbon monoxide (CO) in among the leading causes of injuries and death from poisoning worldwide and nearly 50,000 individuals per year are treated for CO poisoning in the United States.1,2 When CO poisoning is suspected, measurement of the blood carboxyhemoglobin (COHb) is typically performed. The affinity of CO for heme proteins is well known but injuries from CO are precipitated by a combination of cardiovascular effects linked to COHb-mediated hypoxia, hypoperfusion or frank ischemia, and intracellular effects including free radical production and lipid peroxidation. Animal studies indicate that tissue injury results from a combination of hypoxia/ischemia, ATP depletion, excitotoxicity, oxidative stress, and immunological responses.3-13

Given the myriad pathways for injury, it is not surprising that COHb values correlate poorly with clinical outcomes.1,14-20 A COHb level above 25% is used to select patients most likely to benefit from hyperbaric oxygen therapy based on results from a prospective randomized clinical trial.17 Patients over the age of 36 years and those exposed for over 24 h may also benefit from aggressive treatment.21 Even when CO poisoning appears to be relatively mild, however, there are times when delayed neurological sequelae still occur.1,14-18,22,23 CO poisoning most frequently injures the brain and heart. Whereas cardiac enzyme markers are associated with myocardial dysfunction and an elevated risk for long-term cardiac mortality; biochemical markers for brain injury such as neuron-specific enolase and S-100 beta protein have not been found to reliably correlate with severity of poisoning or clinical outcome.24-29

An elevated COHb level is utilized to identify acute environmental CO exposures, but CO poisoning remains a clinical diagnosis because of a wide variety of symptoms and signs that are often shared by other conditions, incomplete understanding of risk factors for morbidity, and a lack of diagnostic tools that are sensitive and specific. Current technology allows for simultaneous measurement of a large number of plasma cytokines, chemokines, and other biomarkers and we reasoned that this approach may offer an improved method to discern the severity of CO poisoning. We have an ongoing protocol in which plasma samples are collected and stored on individuals suspected of suffering from CO poisoning. The goal of this pilot study was to examine plasma samples from patients who had CO poisoning of varying severity and compare the profiles of plasma markers against a group of age- and sex-matched controls. We hypothesized that there may be unique multi-analyte profiles that are correlated with poison severity.

Methods

Patients

A protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board to obtain blood for laboratory analysis from patients undergoing Emergency Department evaluation for suspected acute CO poisoning. A total of 63 samples were selected from among 117 collected between April 19, 2006, and May 22, 2008. Samples from patients with suspected CO poisoning were divided into five groups. Group A were individuals with a history of being found unconscious in a CO-contaminated environment with COHb levels ≥25%. Group B(1) were individuals found unconscious in the CO-contaminated environment but with COHb levels less than 25% and group B(2) were those who had not sustained an interval of unconsciousness but had COHb levels ≥25%. Group C were patients who had not sustained unconsciousness, had COHb levels less than 25%, and CO exposures exceeding 4 h; whereas group D were patients who had not sustained unconsciousness, had COHb levels less than 25%, and CO exposures less than 4 h.

From each severity group, choices were made to achieve nearly equal numbers of men and women and ages spanning 21 years to individuals in their 90s. Details for each group are shown in Supplementary Table A available online at http://informahealthcare.com/doi/suppl/[doinumber]. We then selected 42 plasma samples obtained from individuals with no history of CO exposure who were being seen in our clinics or who were healthy co-workers in the vicinity of the laboratory. Choices for control samples were made to achieve nearly equal numbers of both sexes and spanning a similar age range as among the samples from CO-poisoned patients. Therefore, among the controls five were between 21 and 29 years, two were women and two smoked cigarettes at a frequency of approximately one pack per day (PPD); five controls were between 30 and 39 years, three were women and one smoked one PPD; seven controls were between 40 and 49 years, two were women and one smoked one PPD; eight controls were between 50 and 59 years, two were women and three smoked 0.5–1 PPD; six controls were between 60 and 69 years, three were women and one smoked one PPD; five controls were between 70 and 79 years, two were women; and two controls were between 80 and 89 years, two were women and one smoked 0.5 PPD.

Laboratory analysis

Samples collected by the clinical team were numerically coded and stored in 500 μL aliquots in a −20°C freezer until shipment on dry ice to Rules Based Medicine, Inc. (RBM), Austin, TX, USA. RBM was blinded to patient details and performed analyses on the numerically coded samples using their proprietary Luminex xMAP® technology. This involves performing up to 100 multiplexed, microsphere-based assays in a single reaction vessel by combining optical classification schemes, biochemical assays, flow cytometry, and advanced digital signal processing hardware and software. The data acquisition, analysis, and reporting are performed on a minimum of 100 individual microspheres from each unique multiplexed set. As this was a survey investigation, analyses were performed using RBM’s standard commercially available HumanMAP® antigen panel. Serology results were expressed as the ratio of raw median fluorescence intensity of target-specific, antigen-coupled microspheres versus median fluorescence intensity generated by bovine serum albumin-coupled (negative control) microspheres in the same sample.

Patient management

Clinical management of patients was performed independent of the blood sample collections. All patients received 100% O2 by tight-fitting non-rebreather face mask while they underwent evaluations in the Emergency Department. Patients in groups A and B were treated with a course of three hyperbaric oxygen treatments over a time span of approximately 36 h. Patients in groups C and D were treated with ambient pressure O2 until asymptomatic, then discharged. On discharge from our institution, all patient charts were placed in a file and contact was attempted by telephone within 2 weeks and again 5–6 weeks later. In cases where patients were having any difficulties they were invited to return for follow-up in our clinic when they did not have their own primary physicians. Patients were asked about their status over the intervening time interval. Questions focused on complaints of headache, excessive fatigue, dizziness and problems with ataxia or balance, chest pains, shortness of breath, weakness, numbness/tingling of extremities, difficulty with thinking, concentration, and ability to perform activities of daily living. An affirmative response to questions related to ataxia/balance or difficulty with thinking, concentration, and activities of daily living was taken as evidence of neurological sequelae for this pilot investigation.

Data analysis

For this study we hypothesized that the maximum differences in plasma markers would be observed in patients with the longest duration of CO exposure and the highest clinical severity. Sample size calculations indicated that a total of approximately 60 CO subjects and 40 controls would provide sufficient power to detect differences of 0.75 SDs between exposed and control subjects. Protein values from each CO patient group were compared against the control group values using two-sample, two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum tests with significance level set at 0.05. Because of the exploratory nature of the study, hypothesis corrections for multiple comparisons were not applied; some false-positive results are therefore expected. Direct inspection of the values indicated that while statistically significant differences might exist for some plasma proteins, little relevance could be assigned because levels were undetectable in many plasma samples. For example, betacellin was significantly different in all CO groups versus control. This was deemed of little relevance because the betacellin level was not detectable in 17 of the 42 control samples and in the majority of samples from each CO group. Data were considered of possible clinical validity where levels were detectable in at least 90% of samples from each group. For statistical management, subjects with undetectable plasma protein levels were assigned a value one-half of the lower limit of detection to calculate mean values. Data analyses were performed using Stata Version 10 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Protein value differences

Concentrations of 99 proteins out of 180 analyzed were significantly different from control for at least one CO group and there were 14 proteins where values were significantly different from control in all CO patient groups (Table 1). A complex pattern of differences was found for many proteins. Where differences from control occurred in two or more of the CO patient groups, figures were generated. Acute phase reactant proteins are shown in Fig. 1, chemokines/cytokines in Fig. 2, interleukins in Fig. 3, other proteins associated with inflammatory responses in Fig. 4, growth factors in Fig. 5, hormones in Fig. 6, and other proteins in Fig. 7.

Table 1.

Proteins significantly different from control in all CO patient groups

| Category | Protein | Control, n = 42 | Group A, n = 20 | Group B1, n = 17 | Group B2, n = 11 | Group C, n = 10 | Group D, n = 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute phase reactants | α-2 MG (mg/mL) | 1.22 ± .16 | 1.84 ± 0.22 | 1.96 ± 0.34 | 1.83 ± 0.15 | 2.64 ± 0.48 | 3.42 ± 0.16 |

| vWF (μg/mL) | 9.74 ± 2.10 | 18.2 ± 3.3 | 15.2 ± 3.8 | 18.8 ± 4.9 | 19.4 ± 3.8 | 33.2 ± 2.5 | |

| Chemo-/cytokines | Rantes (ng/mL) | 12.3 ± 2.8 | 17.7 ± 2.8 | 28.8 ± 7.2 | 30.0 ± 8.1 | 38.9 ± 6.7 | 34.8 ± 8.6 |

| Gro-α (μg/mL) | 0.72 ± 0.24 | 0.77 ± 0.98 | 1.21 ± 0.30 | 1.10 ± 0.24 | 1.52 ± 0.21 | 1.14 ± 0.26 | |

| Trail R3 (ng/mL) | 8.30 ± 0.54 | 14.8 ± 1.8 | 11.9 ± 1.5 | 11.4 ± 1.3 | 13.4 ± 2.5 | 13.7 ± 2.0 | |

| Interleukins | IL-13 (ng/mL) | 63.2 ± 3.1 | 44.1 ± 4.1 | 37.5 ± 3.3 | 38.4 ± 3.5 | 33.0 ± 2.0 | 33.5 ± 1.7 |

| Other inflammatory proteins | MMP-2 (ng/mL) | 128.1 ± 47.3 | 276.6 ± 63.2 | 253.0 ± 111.1 | 329.5 ± 73.9 | 272.9 ± 77.7 | 357.8 ± 94.3 |

| MMP-3 (μg/mL) | 6.48 ± 1.31 | 2.44 ± 0.28 | 3.41 ± 0.67 | 2.11 ± 0.30 | 2.94 ± 0.78 | 4.26 ± 0.88 | |

| IgA (mg/mL) | 0.69 ± 0.06 | 0.89 ± 0.09 | 1.10 ± 0.19 | 1.39 ± 0.18 | 1.28 ± 0.22 | 1.29 ± 0.17 | |

| PAI-1 (ng/mL) | 57.1 ± 16.6 | 122.5 ± 32.0 | 194.6 ± 78.9 | 99.2 ± 22.0 | 101.5 ± 27.5 | 136.7 ± 52.6 | |

| Growth factors | IGF-1 (ng/mL) | 102.1 ± 34.0 | 187.3 ± 53.0 | 218.6 ± 81.0 | 346.5 ± 81.4 | 310.8 ± 102.4 | 582.2 ± 120.7 |

| PDGF (μg/mL) | 3.90 ± 1.22 | 4.26 ± 6.23 | 6.17 ± 1.69 | 5.43 ± 1.20 | 7.51 ± 1.59 | 8.36 ± 1.49 | |

| Hormones | Prolactin (ng/mL) | 1.69 ± 0.50 | 2.43 ± 0.80 | 3.11 ± 1.22 | 3.48 ± 1.26 | 4.24 ± 1.94 | 13.6 ± 3.9 |

| Other proteins | SGOT (μg/mL) | 7.53 ± 0.80 | 5.24 ± 0.64 | 4.14 ± 0.95 | 5.33 ± 0.81 | 3.53 ± 0.65 | 1.71 ± 0.36 |

Values are mean ± SE for specified proteins; all values in CO groups were significantly different from control.

Abbreviations in the table are as follows: α2-MG, alpha-2 macroglobulin; Gro-α, CXCR2 ligand growth-related oncogene; IgA, immunoglobulin A; IGF-1, insulin-like growth factor-1; IL-13, interleukin-13; MMP-2, metalloproteinase-2; PAI-1, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1; PDGF, platelet-derived growth factor; RANTES, regulated on activated, normal T expressed and secreted chemokine; SGOT, serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase; TRAIL-R3, tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand decoy receptor; and vWF, von Willebrand factor.

Fig. 1.

Plasma acute phase reactants found to be significantly elevated in two or more of the CO patient groups. Mean values ± SE for control and each of the five CO patient groups are shown. *Values are significantly different from control. Abbreviation is as follows: vWF, von Willebrand factor.

Fig. 2.

Plasma chemokines and cytokines found to be significantly different from control in two or more of the CO patient groups. Mean values ± SE for control and each of the five CO patient groups are shown. *Values are significantly different from control. Abbreviations are as follows: RANTES, regulated on activated, normal T expressed and secreted chemokine; Gro-α, growth-related oncogene; TRAIL-R3, tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand decoy receptor; ENA-78, epithelial cell-derived neutrophil-activating peptide 78; PARC, pulmonary and activation-regulated chemokine; MCP-1, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; MDC, macrophage-derived chemokine.

Fig. 3.

Plasma interleukin (IL) proteins found to be significantly different from control in two or more of the CO patient groups. Mean values ± SE for control and each of the five CO patient groups are shown. *Values are significantly different from control.

Fig. 4.

Additional plasma proteins associated with inflammatory responses found to be significantly different from control in two or more of the CO patient groups. Mean values ± SE for control and each of the five CO patient groups are shown. *Values are significantly different from control. Abbreviations are as follows: MMP, metalloproteinase; IgA, immunoglobulin A; PAI-1, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1.

Fig. 5.

Plasma growth factors found to be significantly different from control in two or more of the CO patient groups. Mean values ± SE for control and each of the five CO patient groups are shown. *Values are significantly different from control. Abbreviations are as follows: HBEGF, heparin binding endothelial growth factor; IGF-1, insulin-like growth factor; PDGF, platelet-derived growth factor; EGF-R, endothelial growth factor receptor; FGF-basic, fibroblast growth factor-basic.

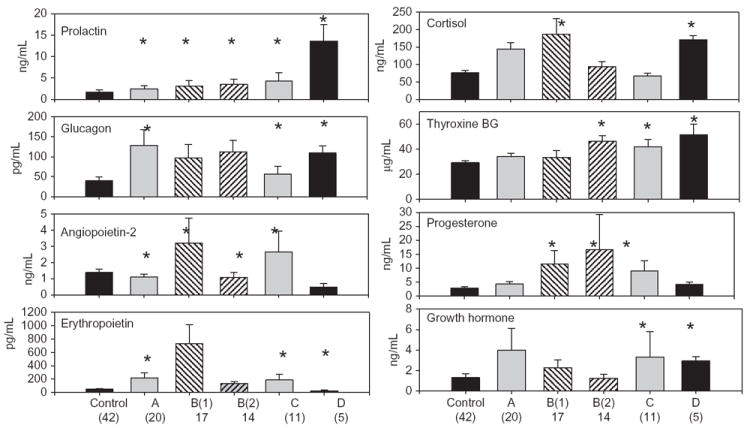

Fig. 6.

Plasma hormones found to be significantly different from control in two or more of the CO patient groups. Mean values ± SE for control and each of the five CO patient groups are shown. *Values are significantly different from control.

Fig. 7.

General plasma proteins found to be significantly different from control in two or more of the CO patient groups. Mean values for control and each of the five CO patient groups are shown. *Values are significantly different from control.

A number of proteins were found to differ from control in only one of the CO patient groups and they are shown in Table 2. There were eight proteins significantly different in group A CO patients. Two proteins were lower in CO patients (hemofiltration chemotactic cytokine-4 and stem cell factor) and six were higher than control (cancer antigen 19-9, intercellular adhesion molecule-1, macrophage inflammatory protein-1β, prostatic acid phosphatase, cytochrome P450 antibody, and histone H4 antibody). Group B1 had significantly higher levels than control for creatine kinase-MB and myoglobin. No group B1 patients exhibited ischemic changes on EKG and none suffered cardiovascular dysfunction. Group B2 had higher values from control in three proteins: alpha fetoprotein, follicle-stimulating factor, and macrophage colony-stimulating factor; and a lower value for Axl tyrosine kinase receptor. There were a notable number of proteins elevated in group C and D patients. A majority of these were IgG auto-antibodies.

Table 2.

Plasma proteins different from control in one CO group

| Protein | Control | Group A |

|---|---|---|

| Cancer antigen 19–9 (U/mL) | 4.71 ± 0.67 | 6.76 ± 1.95 |

| ICAM-1 (ng/mL) | 102.7 ± 6.2 | 123.7 ± 9.4 |

| Macrophage inhibitory protein-1B (pg/mL) | 177.3 ± 44.2 | 1850.3 ± 1273.3 |

| Prostatic acid phosphatase (ng/mL) | 0.19 ± 0.02 | 0.48 ± 0.22 |

| Cytochrome P450-Ab | 2.44 ± 0.14 | 3.25 ± 0.31 |

| Histone H4-Ab | 1.80 ± 0.12 | 2.11 ± 0.14 |

| HCC chemokine-4 (ng/mL) | 4.24 ± 0.37 | 3.37 ± 0.63 |

| Stem cell factor (pg/mL) | 273.7 ± 20.4 | 187.6 ± 22.2 |

| Protein | Control | Group B1 |

| CK-MB (ng/mL) | 0.64 ± 0.30 | 1.00 ± 0.34 |

| Myoglobin (ng/mL) | 15.5 ± 3.0 | 90.6 ± 49.8 |

| Protein | Control | Group B2 |

| α-Fetoprotein (ng/mL) | 2.20 ± 0.23 | 8.48 ± 6.07 |

| FSH (ng/mL) | 1.35 ± 0.25 | 5.33 ± 2.52 |

| M-CSF (ng/mL) | 0.21 ± 0.02 | 0.29 ± 0.04 |

| Axl ligand (ng/mL) | 9.08 ± 0.64 | 6.73 ± 0.84 |

| Protein | Control | Group C |

| Thyroid micros. Ab | 5.89 ± 0.61 | 8.88 ± 1.98 |

| Scleroderma-70Ab | 5.02 ± 0.31 | 7.77 ± 1.32 |

| RNP-Ab | 2.38 ± 0.08 | 2.73 ± 0.18 |

| Ribosomal protein-Ab | 2.02 ± 0.07 | 2.29 ± 0.12 |

| Proteinase-3 Ab | 3.79 ± 0.16 | 4.83 ± 0.29 |

| HSP32-Ab | 2.89 ± 0.09 | 3.20 ± 0.21 |

| Histone H1-Ab | 2.90 ± 0.24 | 4.53 ± 0.73 |

| β2-Glycoprotein-Ab | 9.57 ± 1.18 | 16.01 ± 2.98 |

| TIMP-1 (ng/mL) | 79.74 ± 8.00 | 101.21 ± 14.02 |

| Thyroglobulin Ab | 4.04 ± 1.85 | 2.71 ± 0.40 |

| Protein | Control | Group D |

| RNP (c) Ab | 4.11 ± 0.24 | 6.79 ± 1.12 |

| RNP (a) Ab | 3.33 ± 0.36 | 8.14 ± 1.64 |

| HSP90aAb | 7.52 ± 0.61 | 14.28 ± 3.69 |

| Collagen type 2 Ab | 1.76 ± 0.24 | 3.25 ± 0.59 |

| Interelukin-12p70 (pg/mL) | 63.4 ± 1.51 | 73.2 ± 4.60 |

| TECK (ng/mL) | 27.6 ± 2.96 | 13.27 ± 2.96 |

Values are mean ± SE for specified proteins; CO group values are significantly different from control.

Abbreviations in the table are as follows: Ab, IgG auto-antibody against the identified protein; Axl, Axl tyrosine kinase receptor; CA 19-9, cancer antigen 19-9; CK-MB, creatine kinase-MB isozyme; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; HSP, heat shock protein; HCC-4, hemofiltration chemotactic cytokine-4; ICAM-1, intercellular adhesion molecule-1; M-CSF, macrophage colony-stimulating factor; MIP-1β, macrophage inflammatory protein-1β; RNP, ribonucleoprotein; TECK, thymus expressing chemokine; TIMP, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases. Auto-antibodies were quantified as a fluorescence ratio (see Methods).

Plasma myeloperoxidase concentration has been reported to be elevated in CO-poisoned patients and this was observed in the current trial.12 The average value across all groups was significantly elevated over control [977.0 ± 510.5 ng/mL (mean ± SE) versus 452.1 ± 107.1, p < 0.05, t-test] but it was not significantly elevated for any individual CO patient group.

Neurological sequelae

Patient outcomes for this preliminary investigation were evaluated by telephone contact. Seven patients reported difficulties that were deemed as possible neurological sequelae. Table 3 shows the complaints each reported. The small sampling does not provide sufficient statistical power to discern plasma marker differences in these individuals versus other patients or the control group. Three proteins exhibited a trend that differed from control and the other CO groups. Antibody against heat shock protein 90 was lower than in all other groups, whereas tumor necrosis factor-α and antibody to ribosomal nuclear protein(c) was higher than all groups.

Table 3.

Patients who reported symptoms that could be neurological sequelae

| Group | Age/sex | Complaints |

|---|---|---|

| A | 21 F | Impaired thinking, chronic fatigue, anxiety at 3 weeks – symptoms were resolved at 7 weeks |

| A | 47 F | Impaired balance at 2.5 weeks post poisoning – symptoms were resolved at 8 weeks |

| A | 50 F | Severe daily bitemporal headache at 2 weeks post-poisoning that was resolved at 7 weeks |

| A | 50 M | Anxiety and depression at 3 weeks post-poisoning more severe than prior to his suicide attempt. No further follow up was achieved on this patient |

| B1 | 49 F | Impaired balance and forgetfulness at 2 weeks post-poisoning. An MRI of the brain at 4 weeks was normal. At 2 years follow-up she stated still suffers mild short-term memory impairment but no headache and has not thought problems warranted any follow-up or evaluation by her physicians |

| B2 | 29 M | Fatigue, headache, and generalized weakness at approximately 1 week post-poisoning. A headache that occurs once every 2–3 weeks has persisted (2.5 years follow-up) |

| C | 33 M | Headache that occurred every 2–4 days from time of poisoning but resolved at 9 weeks post-poisoning |

Smoke inhalation versus other CO sources

Smoke from house fires or a charcoal grill contains numerous caustic agents and may be a more heterogeneous form of CO poisoning than exposures to exhaust from an internal combustion engine or furnace. Because there were 14 proteins significantly different from the control group in all CO poisoning groups, we compared these values from patients exposed to smoke versus those exposed to CO from other sources (Table 4). All plasma protein values were significantly different from control, whereas the values were insignificantly different between the smoke inhalation group and those exposed to CO from other sources.

Table 4.

Plasma proteins values in patients exposed to smoke versus other CO sources (“non-smoke”)

| Protein | Control (n = 42) | Non-smoke (n = 50) | Smoke inhalation (n = 13) |

|---|---|---|---|

| α-2 macroglobulin (mg/mL) | 1.22 ± 0.16 | 2.14 ± 0.16* | 2.02 ± 0.34* |

| vWF (μg/mL) | 9.74 ± 2.10 | 16.26 ± 1.75* | 29.50 ± 5.16* |

| Rantes (ng/mL) | 12.3 ± 2.82 | 27.03 ± 3.38* | 28.71 ± 5.53* |

| Gro-α (μg/mL) | 0.72 ± 0.24 | 1.09 ± 0.12* | 1.03 ± 0.16* |

| Trail R3 (ng/mL) | 8.30 ± 0.54 | 13.10 ± 0.98* | 12.98 ± 1.51* |

| IL-13 (ng/mL) | 63.2 ± 3.1 | 38.6 ± 2.13* | 39.8 ± 3.2* |

| MMP-2 (ng/mL) | 128.1 ± 47.3 | 301.8 ± 44.7* | 244.9 ± 62.7* |

| MMP-3 (μg/mL) | 6.48 ± 1.31 | 2.63 ± 0.25* | 3.46 ± 0.61 * |

| IgA (mg/mL) | 0.69 ± 0.06 | 1.16 ± 0.09* | 1.04 ± 0.13* |

| PAI-1 (ng/mL) | 57.1 ± 16.6 | 117.5 ± 17.9* | 180.4 ± 75.4* |

| IGF-1 (ng/mL) | 102.1 ± 34.0 | 285.7 ± 40.8* | 262.1 ± 90.9* |

| PDGF (μg/mL) | 3.90 ± 1.22 | 5.99 ± 0.66* | 5.28 ± 0.91* |

| Prolactin (ng/mL) | 1.69 ± 0.50 | 3.18 ± 0.50* | 6.99 ± 2.26* |

| SGOT (μg/mL) | 7.53 ± 0.80 | 4.61 ± 0.45* | 3.98 ± 0.64* |

Values are mean ± SE for specified proteins; all values in CO groups were significantly different from control but values in “non-smoke” and smoke inhalation groups were not significantly different from each other

(p < 0.05, ANOVA). Abbreviations are as in Table 1.

Discussion

Our results indicate that CO exposure triggers release of a large variety of proteins into the bloodstream of patients. This suggests that there may be concurrent activation of numerous biochemical pathways. Many proteins are associated with inflammatory responses, which underscore findings from some animal models.12,13 CO exposure will perturb heme protein binding by nitric oxide; induce a variety of proteins including heme oxygenase (HO), superoxide dismutase, and nitric oxide synthase; alter mitochondrial function; and modify production of ATP and reactive oxygen species.9,30-39 Exposure to CO can precipitate leakage of macromolecules from the lungs and systemic vasculature.40-45 Within the vasculature CO can cause platelet-neutrophil aggregation and neutrophil activation.12,46 There is also a growing list of transcription factors and protein kinases altered because of CO exposure.47,48

CO is a ubiquitous environmental toxicant and CO also functions in cell signaling. The major intracellular source of CO is the microsomal HO system consisting of HO enzymes and NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase. Under some circumstances effects linked to HO activity are replicated by CO inhalation. Investigators have delivered CO via exogenous CO ventilation or by infusion of a variety of metal carbonyl-based compounds capable of releasing CO in biological systems.48-51 Using animal models, these interventions have been shown to protect microvascular perfusion and to elicit anti-inflammatory benefits.48,52-55 Pathways for these effects are complex and responses vary with cell type. CO increases production of reactive oxygen species from mitochondria and also some non-mitochondrial sources that can activate one or more protein kinases (e.g., p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase, c-Jun N-terminal kinase), signal transducers (e.g., peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ), transcriptional regulators (e.g., nuclear factor-κB), as well as guanylate cyclase and lead to secondary events such as vasodilation and fibrinolysis.55-61 Therefore, CO is pro-oxidant and secondary or adaptive responses may occur as with hormesis or pre-conditioning.

Adaptive responses associated with experimental CO exposures have prompted consideration of CO as a therapeutic agent.62 Risks associated with this intervention have been viewed as small because the COHb levels achieved in most trials are no greater than those found in cigarette smokers. Reconsideration on this idea may be warranted based on the elucidation of non-hypoxic mechanisms of CO-mediated injuries and results from this investigation. The number of plasma proteins elevated, even when CO exposures appear mild and COHb values are relatively small (e.g., groups C and D), raise concern that the duration and concentration of CO required to cause inflammatory responses in humans is unclear. It is also unknown whether responses associated with elevations in plasma proteins pose long-term health risks and the mechanism(s) for the elevations of some proteins (e.g., auto-antibodies) are obviously unclear at this time. It is of course possible that some vascular responses arise from irritants other than CO. In contrast to experimental trials in animals the exposures in our study are impure, especially with regard to smoke inhalation. Comparison of protein values in patients suffering from smoke inhalation versus CO poisoning from other sources (Table 4) suggest that effects relatable to CO prevail in a majority of cases despite the presence of a variety of other combustion products.

Clearly no single pathway or mechanism can explain the variety of plasma protein values altered by CO poisoning. Many pathways activated by CO are likely to occur concurrently and therefore the effects overlap. Moreover, some variations in plasma protein values among the patient groups may arise because of competing or antagonistic processes linked to CO dose and duration of exposure. For example, oxidative stress responses associated with mitochondria can occur with such low CO concentrations that oxidative phosphorylation is not impaired.47 With more severe CO exposures, however, CO-mediated impairments in O2 delivery may lead to frank hypoxia. This would alter or even inhibit production of some reactive species. Nitric oxide synthase activity requires O2 and is directly inhibited by high CO concentrations.37 Therefore, there may be common biochemical events related to the initial exposure which change as more pathways become activated and others inhibited with higher CO concentrations and/or longer exposure times.

Several epidemiological studies have implicated a link between environmental CO exposures and alteration in plasma proteins, but contradictory responses have been reported. Environmental CO exposures were shown to correlate with elevated C-reactive protein in one trial63 but not another by the same group.64 Plasma fibrinogen was increased in one study,65 decreased in one,66 and unchanged in two.63,67 Other studies have reported an elevation in soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1,63 along with decreases in factor VII,63 serum albumin,67 and prothrombin time.68 Therefore, no conclusions can be drawn at this time on whether low-level environmental exposures may alter plasma inflammatory or coagulation markers.

There are several limitations to our study. We examined plasma proteins in the first blood sample obtained from patients on their arrival at the Emergency Department. Plasma levels vary greatly over time based on the magnitude of protein released from tissue stores and clearance rates, so an obvious question for future studies pertains to whether temporal changes would offer better discrimination of patient groups. This investigation also suffers from the sporadic patient follow-up that was achievable. A number of patients were not reachable for follow-up after their houses burned down and others were unwilling to return for follow-up because they had been transported substantial distances for emergency treatment at our facility.

A prospective study involving use of objective neuropsychological testing is planned as this will be necessary to assess whether variations in plasma proteins provide an objective method for stratifying CO poisoning severity. A major clinical challenge is to identify at-risk patients among those who do not suffer overt loss of consciousness. This would aid clinical decisions on treatment and provide an objective method to compare patients in clinical research.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by grant ES016720 from the NIH. We are deeply indebted to the staff of the Department of Emergency Medicine and Institute for Environmental Medicine for their help and cooperation with obtaining blood samples. In particular, we thank R.N. Mary Chin.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this paper.

References

- 1.Raub JA, Mathieu-Nolf M, Hampson NB, Thom SR. Carbon monoxide poisoning–a public health perspective. Toxicology. 2000;145:1–14. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(99)00217-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hampson NB, Weaver LK. Carbon monoxide poisoning: a new incidence for an old disease. Undersea Hyperb Med. 2007;34:163–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arranz B, Blennow K, Eriksson A, Mansson JE, Marcusson J. Serotonergic, noradrenergic, and dopaminergic measures in suicide brains. Biol Psychiatry. 1997;41:1000–1009. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(96)00239-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ishimaru H, Katoh A, Suzuki H, Fukuta T, Kameyama T, Nabeshima T. Effects of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonists on carbon monoxide-induced brain damage in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Therap. 1992;261:349–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ishimaru H, Nabeshima T, Katoh A, Suzuki H, Fukuta T, Kameyama T. Effects of successive carbon monoxide exposures on delayed neuronal death in mice under the maintenance of normal body temperature. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 1991;179:836–840. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(91)91893-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nabeshima T, Katoh A, Ishimaru H, Yoneda Y, Ogita K, Murase K, Ohtsuka H, Inari K, Fukuta T, Kameyama T. Carbon monoxide-induced delayed amnesia, delayed neuronal death and change in acetylcholine concentration in mice. J Pharm Exp Therap. 1991;256:378–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nabeshima T, Yoshida S, Morinaka H, Kameyama T, Thurkauf A, Rice KC, Jacobson AE, Monn JA, Cho AK. MK-801 ameliorates delayed amnesia, but potentiates acute amnesia induced by CO. Neurosci Lett. 1990;108:321–327. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(90)90661-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Newby MB, Roberts RJ, Bhatnagar RK. Carbon monoxide- and hypoxia-induced effects on catecholamines in the mature and developing rat brain. J Pharmacol Expt Therap. 1978;206:61–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Piantadosi CA, Zhang J, Demchenko IT. Production of hydroxyl radical in the hippocampus after CO hypoxia or hypoxic hypoxia in the rat. Free Radic Biol Med. 1997;22:725–732. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(96)00423-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu Y, Fechter LD. MK-801 protects against carbon monoxide-induced hearing loss. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1995;132:196–202. doi: 10.1006/taap.1995.1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Piantadosi CA, Carraway MS, Suliman HB. Carbon monoxide, oxidative stress and mitochondrial permeability pore transition. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;40:1332–1339. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thom SR, Bhopale V, Han S-T, Clark J, Hardy K. Intravascular neutrophil activation due to carbon monoxide poisoning. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:1239–1248. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200604-557OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thom SR, Bhopale VM, Fisher D, Zhang J, Gimotty P. Delayed neuropathology after carbon monoxide poisoning is immune-mediated. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:13660–13665. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405642101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mathieu D, Wattel F, Mathieu-Nolf M, Durak C, Tempe JP, Bouachour G, Sainty JM. Randomized prospective study comparing the effect of HBO versus 12 hours NBO in non-comatose CO poisoned patients. Undersea Hyperb Med. 1996;23(suppl):7. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raphael JC, Elkharrat D, Guincestre MCJ, Chastang C, Vercken JB, Chasles V, Gajdos P. Trial of normobaric and hyperbaric oxygen for acute carbon monoxide intoxication. Lancet. 1989;2:414–419. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)90592-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thom SR, Taber RL, Mendiguren II, Clark JM, Hardy KR, Fisher AB. Delayed neuropsychologic sequelae after carbon monoxide poisoning: prevention by treatment with hyperbaric oxygen. Ann Emerg Med. 1995;25:474–480. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(95)70261-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weaver LK, Hopkins RO, Chan KJ, Churchill S, Elliott CG, Clemmer TP, Orme JF, Jr, Thomas FO, Morris AH. Hyperbaric oxygen for acute carbon monoxide poisoning. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1057–1067. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choi S. Delayed neurologic sequelae in carbon monoxide intoxication. Arch Neurol. 1983;40:433–435. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1983.04050070063016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hampson NB. Emergency department visits for carbon monoxide poisoning in the Pacific Northwest. J Emerg Med. 1998;16:695–698. doi: 10.1016/s0736-4679(98)00080-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hampson NB, Hauff NM. Carboxyhemoglobin levels in carbon monoxide poisoning: do they correlate with the clinical picture? Am J Emerg Med. 2008;26:665–669. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weaver LK, Valentine K, Hopkins R. Carbon monoxide poisoning: Risk factors for cognitive sequelae and the role of hyperbaric oxygen. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:491–497. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200701-026OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Remick RA, Miles JE. Carbon monoxide poisoning: neurologic and psychiatric sequelae. Can Med Assoc J. 1977;117:654–657. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ryan CM. Memory disturbances following chronic, low-level carbon monoxide exposure. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 1990;5:59–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davutoglu V, Gunay N, Kocoglu H, Gunay NE, Yildirim C, Cavdar M, Tarakcioglu M. Serum levels of NT-ProBNP as an early cardiac marker of carbon monoxide poisoning. Inhal Toxicol. 2006;18:155–158. doi: 10.1080/08958370500305885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kalay N, Ozdogru I, Cetinkaya Y, Eryol NK, Dogan A, Gul I, Inanc T, Ikizceli I, Oguzhan A, Abaci A. Cardiovascular effects of carbon monoxide poisoning. Am J Cardiol. 2007;99:322–324. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Henry CR, Satran D, Lindgren B, Adkinson C, Nicholson CI, Henry TD. Myocardial injury and long-term mortality following moderate to severe carbon monoxide poisoning. J Am Med Assoc. 2006;295:398–402. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.4.398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Satran D, Henry CR, Adkinson C, Nicholson CI, Bracha Y, Henry TD. Cardiovascular manifestations of moderate to severe carbon monoxide poisoning. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:1513–1516. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rasmussen LS, Poulsen MG, Christiansen M, Jansen EC. Biochemical markers for brain damage after carbon monoxide poisoning. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2004;48:469–473. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2004.00362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brvar M, Mozina H, Osredkar J, Mozina M, Noc M, Brucan A, Bunc M. S100B protein in carbon monoxide poisoning: a pilot study. Resuscitation. 2004;61:357–360. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2004.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim KM, Pae HO, Zheng M, Park R, Kim YM, Chung HT. Carbon monoxide induces heme oxygenase-1 via activation of protein kinase R-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase and inhibits endothelial cell apoptosis triggered by endoplasmic reticulum stress. Circ Res. 2007;101:919–927. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.154781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee BS, Heo JH, Kim YM, Shim SM, Pae HO, Kim YM, Chung HT. Carbon monoxide mediates heme oxygenase-1 induction via Nrf2 activation in hepatoma cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;343:965–972. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.03.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakao A, Kaczorowski DJ, Zuckerbraun BS, Lei J, Faleo G, Deguchi K, McCurry KR, Billiar TR, Kanno S. Galantamine and carbon monoxide protect brain microvascular endothelial cells by heme oxygenase-1 induction. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;367:674–679. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.12.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cronje FJ, Carraway MS, Freiberger JJ, Suliman HB, Piantadosi CA. Carbon monoxide actuates O(2)-limited heme degradation in the rat brain. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;37:1802–1812. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zuckerbraun BS, Billiar T, Otterbein SL, Kim PKM, Liu F, Choi AM, Bach FH, Otterbein L. Carbon monoxide protects against liver failure through nitric oxide-induced heme oxygenase 1. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1707–1716. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maulik N, Engelman DT, Watanabe M, Engelman RM, Das DK. Nitric oxide a retrograde messenger for carbon monoxide signaling in ischemic heart. Mol Cell Biochem. 1996;157:75–86. doi: 10.1007/BF00227883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brown SD, Piantadosi CA. Recovery of energy metabolism in rat brain after carbon monoxide hypoxia. J Clin Invest. 1991;89:666–672. doi: 10.1172/JCI115633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thom SR, Ohnishi ST, Ischiropoulos H. Nitric oxide released by platelets inhibits neutrophil B2 integrin function following acute carbon monoxide poisoning. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1994;128:105–110. doi: 10.1006/taap.1994.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thom SR, Xu YA, Ischiropoulos H. Vascular endothelial cells generate peroxynitrite in response to carbon monoxide exposure. Chem Res Toxicol. 1997;10:1023–1031. doi: 10.1021/tx970041h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thom SR, Fisher D, Xu YA, Notarfrancesco K, Ischiropoulos H. Adaptive responses and apoptosis in endothelial cells exposed to carbon monoxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:1305–1310. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.3.1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thom SR, Fisher D, Xu YA, Garner S, Ischiropoulos H. Role of nitric oxide-derived oxidants in vascular injury from carbon monoxide in the rat. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:H984–H992. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.3.H984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thom SR, Ohnishi ST, Fisher D, Xu YA, Ischiropoulos H. Pulmonary vascular stress from carbon monoxide. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1999;154:12–19. doi: 10.1006/taap.1998.8553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kjeldsen K, Astrup P, Wanstrup J. Ultrastructural intimal changes in the rabbit aorta after a moderate carbon monoxide exposure. Altherosclerosis. 1972;16:67–82. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(72)90009-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maurer FW. The effects of carbon monoxide anoxemia on the flow and composition of cervical lymph. Am J Physiol. 1941;133:170–179. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Parving HH, Ohlsson K, Buchardt-Hansen HJ, et al. Effect of carbon monoxide on capillary permeability to ablumin and macroglobulin. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1972;29:381–388. doi: 10.3109/00365517209080254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Petersen FB, Siggaard-Anderson J, Kristensen JH, Kjeldsen K. Capillary filtration rate on the human calf during exposure to carbon monoxide and hypoxia (3454m) Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1968;103:49–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thom SR. Leukocytes in carbon monoxide-mediated brain oxidative injury. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1993;123:234–247. doi: 10.1006/taap.1993.1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Piantadosi CA. Carbon monoxide, reactive oxygen signaling, and oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;45:562–569. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bilban M, Haschemi A, Wegiel B, Chin BY, Wagner O, Otterbein LE. Heme oxygenase and carbon monoxide initiate homeostatic signaling. J Mol Med. 2008;86:267–279. doi: 10.1007/s00109-007-0276-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Motterlini R, Mann BE, Johnson TR, Clark JE, Foresti R, Green CJ. Bioactivity and pharmacological actions of carbon monoxide-releasing molecules. Curr Pharm Des. 2003;9:2525–2539. doi: 10.2174/1381612033453785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Motterlini R, Clark JE, Foresti R, Sarathchandra P, Mann BE, Green CJ. Carbon monoxide-releasing molecules: characterization of biochemical and vascular activities. Circ Res. 2002;90:E17–E24. doi: 10.1161/hh0202.104530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Motterlini R, Sawle P, Hammad J, Bains S, Alberto R, Foresti R, Green CJ. CORM-A1: a new pharmacologically active carbon monoxide-releasing molecule. FASEB J. 2005;19:284–286. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2169fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cepinskas G, Katada K, Bihari A, Potter RF. Carbon monoxide liberated from carbon monoxide-releasing molecule CORM-2 attenuates inflammation in the liver of septic mice. Am J Physiol. 2008;294:G184–G191. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00348.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Clark JE, Naughton P, Shurey S, Green CJ, Johnson TR, Mann BE, Foresti R, Motterlini R. Cardioprotective actions by a water-soluble carbon monoxide-releasing molecule. Circ Res. 2003;93:e2–e8. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000084381.86567.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Guo Y, Stein AB, Wu WJ, Tan W, Zhu X, Li QH, Dawn B, Motterlini R, Bolli R. Administration of a CO-releasing molecule at the time of reperfusion reduces infarct size in vivo. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286:H1649–H1653. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00971.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ryter SW, Otterbein LE. Carbon monoxide in biology and medicine. BioEssays. 2004;26:270–280. doi: 10.1002/bies.20005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wijayanti N, Huber S, Samoylenko A, Kietzmann T. Role of NF-kappaB and p38 MAP kinase signaling pathways in the lipopolysaccharide-dependent activation of heme oxygenase-1 gene expression. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2004;6:802–810. doi: 10.1089/ars.2004.6.802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fujita T, Toda K, Karimova A, Yan SF, Naka Y, Yet SF, Pinsky DJ. Paradoxical rescue from ischemic lung injury by inhaled carbon monoxide driven by derepression of fibrinolysis. Nat Med. 2001;7:598–604. doi: 10.1038/87929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mishra S, Fujita T, Lama VN, Nam D, Liao H, Okada M, Minamoto K, Yoshikawa Y, Harada H, Pinsky DJ. Carbon monoxide rescues ischemic lungs by interrupting MAPK-driven expression of early growth response 1 gene and its downstream target genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:5191–5196. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600241103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Morse D, Pischke SE, Zhou Z, Davis RJ, Flavell RA, Loop T, Otterbein SL, Otterbein LE, Choi AM. Suppression of inflammatory cytokine production by carbon monoxide involves the JNK pathway and AP-1. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:36993–36998. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302942200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Arruda MA, Rossi AG, de Freitas MS, Barja-Fidalgo C, Graça-Souza AV. Heme inhibits human neutrophil apoptosis: involvement of phosphoinositide 3-kinase, MAPK, and NF-kappaB. J Immunol. 2004;173:2023–2030. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.3.2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Soares MP, Seldon MP, Gregoire IP, Vassilevskaia T, Berberat PO, Yu J, Tsui TY, Bach FH. Heme oxygenase-1 modulates the expression of adhesion molecules associated with endothelial cell activation. J Immunol. 2004;172:3553–3563. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.6.3553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Scott JR, Chin BY, Bilban MH, Otterbein LE. Restoring HOmeostasis: is heme oxygenase-1 ready for the clinic? Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2007;28:200–205. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ruckerl R, Ibald-Mulli A, Koenig W, Schneider A, Woelke G, Cyrys J, Heinrich J, Marder V, Frampton M, Wichmann HE, Peters A. Air pollution and markers of inflammation and coagulation in patients with coronary heart disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:432–441. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200507-1123OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ruckerl R, Greven S, Ljungman P, Aalto P, Antoniades C, Bellander T, Berglind N, Chrysohoou C, Forastiere F, Jacquemin B, von Klot S, Koenig W, Kuchenhoff H, Lanki T, Pekkanen J, Perucci CA, Schneider A, Sunyer J, Peters A. Air pollution and inflammation (interleukin-6, C-reactive protein, fibrinogen) in myocardial infarction survivors. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115:1072–1080. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pekkanen J, Brunner EJ, Anderson HR, Tiittanen P, Atkinson RW. Daily concentrations of air pollution and plasma fibrinogen in London. Occup Environ Med. 2000;57:818–822. doi: 10.1136/oem.57.12.818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Steinvil A, Kordova-Biezuner L, Shapira I, Berliner S, Rogowski O. Short-term exposure to air pollution and inflammation-sensitive biomarkers. Environ Res. 2008;106:51–61. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Liao D, Heiss G, Chinchilli VM, Duan Y, Folsom AR, Lin HM, Salomaa V. Association of criteria pollutants with plasma hemostatic/inflammatory markers: a population-based study. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol. 2005;15:319–328. doi: 10.1038/sj.jea.7500408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Baccarelli A, Zanobetti A, Martinelli I, Grillo P, Hou L, Giacomini S, Bonzini M, Lanzani G, Mannucci PM, Bertazzi PA, Schneider A, Woelke G, Cyrys J, Heinrich J, Marder V, Frampton M, Wichmann HE, Peters A. Effects of exposure to air pollution on blood coagulation. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5:252–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.