Abstract

Interleukin (IL)-7 is a central cytokine that controls homeostasis of the CD4 T lymphocyte pool. Here we show on human primary cells that IL-7 binds to preassembled receptors made up of proprietary chain IL-7Rα and the common chain γc shared with IL-2, -4, -9, -15, and -21 receptors. Upon IL-7 binding, both chains are driven in cholesterol- and sphingomyelin-rich rafts where associated signaling proteins Jak1, Jak3, STAT1, -3, and -5 are found to be phosphorylated. Meanwhile the IL-7·IL-7R complex interacts with the cytoskeleton that halts its diffusion as measured by single molecule fluorescence autocorrelated spectroscopy monitored by microimaging. Comparative immunoprecipitations of IL-7Rα signaling complex from non-stimulated and IL-7-stimulated cells confirmed recruitment of proteins such as STATs, but many others were also identified by mass spectrometry from two-dimensional gels. Among recruited proteins, two-thirds are involved in cytoskeleton and raft formation. Thus, early events leading to IL-7 signal transduction involve its receptor compartmentalization into membrane nanodomains and cytoskeleton recruitment.

Keywords: Cytoskeleton, Interleukin, Lipid Raft, Mass Spectrometry (MS), Signal Transduction, FCS, IL-7, Receptor Assembly, Signaling Complex, T-cell

Introduction

Interleukin (IL)3-7 is a central cytokine that regulates CD4 T cell homeostasis (1–5). It is secreted by a number of cell sources: stromal cells in the red marrow and thymus, keratinocytes, dendritic cells, and endothelial cells (6). CD4 T cell lymphopenia increases the expression of circulating IL-7, resulting in the expansion of CD4 T cell subsets by increasing the metabolism and inactivating cell cycle inhibitors (7, 8). It also lowers the threshold of TCR activation by foreign and self-antigens (9, 10), and it prolongs these effects by inducing anti-apoptotic factors Bcl2 and Bcl-xL, and inhibiting pro-apoptotic factors such as Bad and Bax (11–13).

IL-7 binds to its receptor, IL-7R, which is made up of two glycosylated chains anchored to the membrane by a single helical transmembrane domain (14): IL-7Rα and the common γ chain. IL-7Rα, also known as CD127 (65 kDa, 459 amino acids), is also shared by thymic stromal lymphopoietin (15, 16). The common γ chain (γc), also known as CD132 (56 kDa, 369 amino acids), is shared by IL-2, -4, -9, -15, and -21 (5). IL-7Rα is highly and γc weakly expressed at the surface of resting CD4 T cells. Their stimulation by IL-7 down-regulates the expression of IL-7Rα, which disappears from the cell surface after 12 h, and up-regulates quickly the expression of γc, optimal after 12 h (17–20). IL-7 has high affinity for the IL-7R heterodimer (Kd ∼ 35 × 10−12 m), low affinity for its single proprietary chain IL-7Rα (Kd ∼ 3 × 10−9 m), and very low affinity for γc (Kd > 250 × 10−9 m) (21). IL-7 has been cocrystallized with the extracellular fragment of IL-7Rα in the absence of any γc fragment (22). IL-7Rα has a long cytoplasmic domain (195 amino acids), which is responsible for binding a large array of proteins involved in the signaling pathways that support cell survival and proliferation pathways (4, 23). These include Jak1, which is involved in the Jak/STAT pathway. The γc chain has a shorter cytoplasmic domain (86 amino acids), which binds Jak3. Both Jak1 and Jak3, carried by their respective receptor chains, are required to phosphorylate themselves, then the IL-7Rα carboxyl-terminal Tyr (Tyr(P)-456) upon IL-7 binding. This Tyr(P)-456 provides a single binding site for STAT1, STAT3, and mainly STAT5a and STAT5b. Bound STATs are then phosphorylated by the activated pJak1·pJak3 complex (4, 23). After phosphorylation, the STATs dissociate, dimerize, and are translocated into the nucleus where they induce transcription of gene clusters involved in cell programs (23). Mitogen-activated protein kinase and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathways are also triggered by IL-7·IL-7R binding and give rise to mitogenic and anti-apoptotic signals. Although a wealth of information is available on the various kinases involved in IL-7 signal transduction, less is known of the IL-7 signaling complexes.

This work aimed to describe the IL-7R chain assembly process and the protein content of the signaling complexes before and after IL-7 binding. Our observations in primary CD4 T lymphocytes were based on kinetic investigations of fluorescent-tagged cell components followed by confocal microscopy on living cells, and on biochemical investigations of purified complexes by immunoblotting and mass spectrometry. For the first time, a γc-cytokine receptor is shown to be associated with lipid rafts and cytoskeleton is shown to be involved in IL-7R compartmentalization at the level of a single complex in a single living primary human cell. This approach, at the molecular level and in real time, describes the very first steps in IL-7 response initiation that is crucial to CD4 T cell activation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Human CD4 T Lymphocyte Purification

Venous blood was obtained from healthy volunteers through the EFS (Etablissement Francais du Sang, Centre Cabanel, Paris). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were purified by density gradient centrifugation on Lymphoprep solution (Axis-Schield). CD3+/CD4+ NT cells were prepared from human peripheral blood mononuclear cells by separation on magnetic beads (CD4+ negative purification kit, Miltenyi Biotec). The enriched CD4 T cell population contained >95% CD3+/CD4+ cells. The recovered CD4 T cells were not activated as controlled by the absence of CD69 and CD25 expression.

Cell purity of preparations and IL-7R chain expression at the cell surface were analyzed by flow cytometry with labeled antibodies. Cells were harvested and resuspended in 50 μl of cytometer buffer (phosphate-buffered saline with 0.02% sodium azide and 5% fetal bovine serum) and labeled for 1 h at 4 °C with antibodies to CD4 (eBioscience). CD4 receptor expression was measured by flow cytometry in CD4 T cells on a Cyan LXTM cytometer (DakoCytomation). Data were acquired with Summit version 4.1 software (Dako) and analyzed using FlowJo version 8.3.3 software (Tree Star).

For cytokine activation, CD4 T cells were resuspended at 106 cells/ml in RPMI 1640 medium (Lonza, Verviers, Belgium) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum, 50 mm HEPES, pH 7.4, glutamine, penicillin, streptomycin, and fungizone (complete medium) in 24-well plates, were treated with 1 nm recombinant glycosylated human IL-7 (Cytheris) at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere.

FCS and FCCS Analysis of IL-7R Chain Assembly and Diffusion at the Surface of Living Cells

Fluorescence auto- and cross-correlated spectroscopy (FCS/FCCS) measurements were made on living cells using an inverted laser scanning confocal microscope (LSM510), combined with a ConfoCor2 FCS system (Zeiss). Depth of field was spatially filtered through a 30–300-μm pinhole and fluorescence light was split into two detection channels with the following excitation/emission wavelengths: Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen) (Ar, 488 nm/550–600 nm) and Alexa Fluor 633 (Invitrogen) (He/Ne, 633 nm/BP680 nm). FCS and image data were acquired and then analyzed by LSM software (Zeiss). The observation volumes of the LSM and the ConfoCor systems were aligned by bleaching spots with the ConfoCor in a dried layer of rhodamine-6G (Sigma) on a 0.16-mm glass slide from cross-hair positions in LSM images. Pinhole setting, volume overlap, and ConfoCor/LSM alignment were processed before each measurement session when laser power and temperature were at equilibrium. Pinhole x-, y-, and z-positions were carefully aligned for both channels 488 and 633 nm, and their confocal emission volume overlap was tuned by adjusting the collimator. Confocal volume was calibrated with rhodamine-6G and tested with beads as described under supplemental Fig. S1. Autocorrelation and cross-correlation functions were extracted from fluorescence intensity fluctuations during 30–60-s acquisition times and fitted to three-, two-, or three-/two-dimensional mixed mathematical models according to Ref. 24 with Origin software (OriginLab).

Three-dimensional diffusions of rhodamine-6G, streptavidin-Alexa 488 (SA488, Invitrogen), streptavidin-Alexa 633 (SA633, Invitrogen), IgG-biotin·streptavidin-Alexa 488 (mAbb·SA488), and IL-7-biotin·streptavidin-Alexa 633 (IL-7b·SA633) were analyzed in RPMI medium at 37 °C. Autocorrelation functions (ACF) of fluorescent particle three-dimensional diffusion were fitted with the following model,

|

where N is the number of fluorescent molecules in the actual detection volume defined by Veff = π3/2ω03, and s is the structural parameter representing its shape, as derived from the ratio between its axial and lateral radius s = z0/ω0, i is the component number, ftriplet and τtriplet are the fraction and diffusion time of particles with their fluorophore in the triplet state, fi and τi are the fraction and diffusion time of fluorescent component i (24). The structure factor s was approximated to 5.0 from best fits for ω02 in the range 50 × 103—150 × 103 nm2. Below 50 × 103 and beyond 150 × 103 nm2, s deviation indicated that the volume shape was clearly affected (waved zones are shown in supplemental Fig. S1) and restricted the exploration field with our commercial system. The following values were calculated for τd at ω02 = 70 × 103 nm2 in RPMI at 37 °C: τD[SA488] = 243 μs, τd[SA633] = 245 μs, τD[mAbb·SA488] = 312 μs. Up to 10 ACF were recorded for each of 6 to 10 ω02 values. τD were averaged from these 10 ACF per ω02 values, fitted with Equation 1 for one component. Effective lateral diffusion rates Deff were calculated from the linear regression of the diffusion time τd versus ω02 plots.

Accordingly, the following values were calculated for controls in RPMI at 37 °C: Deff(SA488sol) = 72 μm2/s, Deff(SA633sol) = 72 μm2/s, and Deff(mAbb/SA488sol) = 56 μm2/s.

CD4 T cells were observed before and 10 min after addition of 1, 10, and 100 nm IL-7. When indicated, cells were washed twice in RPMI, 10 mm HEPES, then treated at 37 °C in 10 mm RPMI/HEPES either for 25 min with 2 and 10 μm cytochalasin D (CytD, Sigma) or for 25 min with cholesterase oxidase (1 unit/ml, Sigma) and/or for 5 min with sphingomyelinase (0.1 unit/ml, Sigma) as described previously (25) prior to adding IL-7. IL-7Rα and γc chains expressed at the cell surface were, respectively, labeled with anti-IL-7Rα (mAb 40131, R&D Systems Inc.) tagged with anti-mouse IgG-Alexa 488 (sAb/A488, Invitrogen) or biotinylated anti-IL-7Rα (mAbb) tagged with streptavidin-Alexa 488 and biotinylated anti-γc (mAbb TugH4, Pharmingen) tagged with streptavidin-Alexa 633 in a 1:4 molar ratio to avoid mAb aggregation by tetrameric streptavidins. Antibodies were used in large excess to avoid Ab-induced aggregation of receptors. Biotinylated IL-7 was labeled with streptavidin-Alexa 633 (IL-7b·SA633) in a 1:4 molar ratio as well to avoid cytokine aggregation. Receptor diffusion measurements were acquired within a 10–30-min time frame in culture medium to minimize internalization effects and IgG-induced receptor aggregation. Confocal volumes in the FCS optical system and imaging laser scanning microscope were adjusted and centered on the cytoplasmic membrane. All images and FCS data were acquired at 37 °C using a thermostated dish holder and objective ring. Ten 30-s acquisitions were recorded at 6 pinhole values over 10 points spread over a 3 × 3-μm square of a single cell immobilized on poly-l-lysine-coated glass slides at the bottom of the dish. Briefly, autocorrelation curves, G(τ), were fitted with one up to three components: one fast three-dimension diffusion based component (free mAbb·SA or IL-7b·SA) characterized by its diffusion time in the confocal volume (τD,fast) and described by Equation 1, then one intermediate (τD,inter) and one slow (τD,slow) two-dimensional diffusion-based component as described by Equation 3, corresponding to the membrane-embedded receptor chains in different aggregation states.

|

Overall the model used with 3 components is given by Equation 4.

|

where ffast, finter, and fslow are relative fractions of component populations. Effective diffusion rates Deff were also extracted from the linear regression of τD versus the observed membrane surface area ω02 and confinement time, τ0 at the y intercept at the waist origin, ω02 = 0 in Equation 2. We counted the diffusing particles in Veff from the extrapolation at the origin of autocorrelation functions.

Autocorrelation functions were normalized for comparison with Equation 6.

Cross-correlation functions (CCF) between IL-7Rα·mAbb· SA488 and IL-7b·SA633 were fitted using the following three-dimensional (Equation 7) and two-dimensional (Equation 8) diffusion models, respectively

|

|

where τij is the diffusion time of the complex IL-7Rα·mAbb·SA488·IL-7b·SA633 considered as a unique species carrying both fluorophores mostly anchored to the membrane. SA488/SA633 fluorescence cross-talk was corrected from a single labeling experiment of the same system recorded in both channels (24).

Among our major concerns was receptor aggregation induced by antibodies or streptavidin, and receptor internalization. Diffusion plots (Equation 2) give control of receptor chain aggregation slowing down their diffusion with increasing time: the plot is curving up when acquisition starts from small to large ω02 as observed for diffusion of IL-7Rα labeled with the primary·secondary antibody complex mAb·sAb·A488 beyond 10 min of acquisition time and beyond 20–30 min with mAbb·SA488. Controls were done with either free unlabeled streptavidin, biotin (Sigma), or mouse IgG added in culture medium. Usual conditions applied to lower receptor internalization were unfavorable: decrease of temperature affected membrane fluidity and cytoskeleton adhesion, and deoxyglucose and sodium azide affected receptor compartmentalization. The linearity of the diffusion plot (Equation 2) was used to reject acquisitions affected by internalization events and/or antibody aggregation.

Cell Lysate Ultracentrifugation through a Sucrose Gradient

Purified primary CD4 T lymphocytes were stimulated or not by IL-7 (2 nm, 5 min), then harvested, cooled by adding ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline, centrifuged, and lysed in 0.5% Triton X-100 buffer (50 mm Tris/HCl, pH 7.4, 5 mm EGTA, 5 mm EDTA, 30 mm NaF, 20 mm Na-pyrophosphate, 1 mm Na3VO4, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 10 μm leupeptin). Briefly, 300 μl of lysate supernatant from 5 × 106 cells was loaded on the top of 5 ml of a preformed 5–40% sucrose/Triton buffer gradient and centrifuged for 16 h at 50 krpm using a SW50 rotor in a Beckman ultracentrifuge. Tube contents were divided into 18 280-μl samples and 60 μl were loaded on SDS-PAGE (7% acrylamide-bisacrylamide) and transferred onto a Hybond-ECL nitrocellulose membrane (GE Healthcare) overnight at 4 °C. Membranes were saturated with bovine serum albumin (Sigma), incubated with primary antibodies, and washed in TBS, 0.5% Tween 20 buffer before being incubated with horseradish peroxidase-coupled anti-mouse (Jackson), anti-rat (Amersham Biosciences), or anti-goat (Jackson) secondary antibodies. Proteins were then revealed by ECL-plus Western blotting detection reagents (GE Healthcare). Western blots were analyzed with anti-IL-7Rα (mAb 40131, R&D Systems), anti-γc (pAb AF284, R&D Systems, or mAb TugH4, Pharmingen), and anti-flottilin-1 as a detergent-resistant membrane domain (DRM) marker (mAb 610821, BD Biosciences).

When indicated, pooled fractions of the sucrose gradient were immunoprecipitated using anti-IL-7Rα. Immunoprecipitated proteins were loaded on SDS-PAGE (7% acrylamide-bisacrylamide) and analyzed by Western blotting using anti-Tyr(P) (Ab 4G10, Upstate), anti-pJak (Tyr(p)1022/1023, Ab 44–422G, BIOSOURCE), anti-pSTAT3 (Tyr(p)705, Ab 3E2, Cell Signaling), and anti-pSTAT5 (Tyr(p)694, Ab 14H2, Cell Signaling).

Immunoprecipitation of IL-7Rα-bound Proteins for Two-dimensional PAGE and MS Analysis

After 8–24 h of incubation at 37 °C, purified primary CD4 T lymphocytes were activated with or without 1 nm IL-7 for 5 min. Cells were harvested, washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline, and lysed for 20 min on ice with 0.5% Triton X-100 lysis buffer as described above. Immunoprecipitations were processed from lysates containing 350 μg (two-dimensional PAGE) of proteins pulled down with anti-IL-7Rα mAb (mAb 40131, R&D Systems) for 1 h at 4 °C on a spinning wheel with 250 pm IL-7 when necessary. G-protein coupled-Sepharose beads (GE Healthcare) were then added for 1 h at 4 °C. After four washes in 0.5% Triton X-100 buffer containing 250 pm IL-7 when necessary, samples were resuspended in Triton/urea buffer for IEF (7 m urea, 2 m thiourea, 1 m dithiothreitol, 0.5% ampholyte, 0.5% Triton X-100, 50 mm Tris/HCl, pH 7.4, 5 mm EGTA, 5 mm EDTA, 30 mm NaF, 20 mm sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mm Na3VO4, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 10 μm leupeptin).

Western Blot Analysis

Immunoprecipitated protein samples used for two-dimensional PAGE were also analyzed by Western blotting. Immunoprecipitated fractions from lysed non-stimulated and IL-7-stimulated CD4 T cells were loaded on one-dimensional SDS-PAGE (7% acrylamide-bisacrylamide) and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane treated for Western blotting as described above. The following primary antibodies were used: anti-IL-7Rα (mAb 40131, R&D Systems), anti-γc (pAb AF284, R&D Systems), anti-Jak1 (pAb sc-295, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-Jak3 (pAb sc-513, SCB), anti-STAT1(pAb sc-592, SCB), anti-STAT3 (pAb sc-482, SCB), anti-STAT5 (pAb sc-835, SCB), anti-ERK1/2 (pAb 9102, Cell Signaling), anti-actin (pAb sc-1616, SCB), anti-α-tubulin (mAb sc-5286, SCB), anti-ezrin (rabbit IgG pAb, kind gift of Dr. M. Arpin, Institut Curie), and anti-moesin (mAb 610401, BD Biosciences).

Two-dimensional PAGE Analysis of IL-7R Signaling Complex Components, Identification by Mass Spectrometry

IEF gel strips (16 cm, pH 3–10, Bio-Rad) were loaded with IP proteins with anti-IL-7Rα from 350 μg of proteins from non-stimulated or IL-7-stimulated CD4 T cell lysates according to the Bio-Rad procedure. Strips equilibrated with dithiothreitol buffer, then iodoacetamide buffer were loaded over 16 × 16-cm SDS-PAGE (12% acrylamide-bisacrylamide). The gels were stained with Sypro-Ruby (Invitrogen). Acrylamide gel plugs were cut and removed from Sypro-stained spots using an automat and processed as described previously (21). Trypsin-proteolyzed samples were loaded by the robot onto the MALDI plate target, then dried and mass spectra were acquired as described previously (21) on a 4800 MALDI/TOF/TOF Analyzer (Applied Biosystems) performing MS and MS/MS in automatic mode (3000 laser shots). Subspectra of 50 laser shots were accumulated for the 15 most intense m/z peaks from MS followed by air collision-induced peptide fragmentation (2 kV) and MS/MS analysis to determine the peptide sequence. Trypsin autolysis peptides were used for calibration. Mascot GPS Explorer version 3.6 software (Matrix Science) was used to scout Swissprot data base release 94 (SIB, EBI) supplemented with variant and signal-free sequences. Only monoisotopic masses between 800 and 4000 m/z were used with a maximum peptide mass error of 50 ppm for MS and 0.3 Da for MS/MS. One incomplete cleavage was allowed per peptide and possible methionine oxidation and cysteine derivatization were considered.

RESULTS

Preassembled Free IL-7R Is Compartmentalized after IL-7 Binding

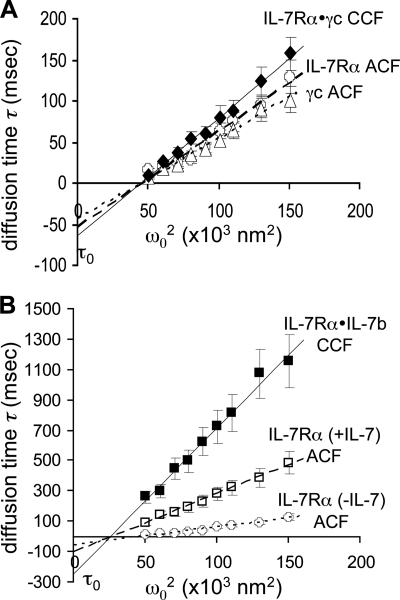

The mechanism of IL-7Rα and γc assembly to form the active receptor, and involvement of IL-7 in this formation were analyzed by FCS measured by confocal microscopy at the surface of living primary human CD4 T lymphocytes. Fluorescent particle species were separated and quantified from their diffusion times in the microscope confocal volume. Diffusion times τD of individual receptor chains IL-7Rα (Fig. 1E, e, τD = 25.8 ms for ω02 = 70 × 103 nm2) and γc (Fig. 1E, d, τD = 23.7 ms) were calculated from autocorrelation functions of fluorescence intensity fluctuations of their labels, fitted with adapted diffusion models (Fig. 1, A–C) for increasing sizes of the observed membrane surface areas (Fig. 1F). ACF were normalized with Equation 6 for comparison. IL-7Rα and γc effective diffusion rates Deff were extracted from the plots shown in Fig. 2A. Deff is inversely correlated to slopes of diffusion times versus observed membrane surface areas ω02: accordingly with Equation 2, Deff = 0.215 ± 0.025 and 0.252 ± 0.030 μm2/s, for IL-7Rα and γc, respectively. Diffusion time of the IL-7Rα·γc complex was calculated from cross-correlation functions of both channel fluorescence intensity fluctuations: one for IL-7Rα·mAbb·A488 and the other for γc·mAbb·SA633 as detailed in Fig. 1E, f. The diffusion rate for the IL-7Rα·γc complex was determined to be Deff = 0.173 ± 0.026 μm2/s, about 20% slower than for IL-7Rα (Fig. 2A). Oligomerization does not significantly affect the IL-7Rα diffusion rate. Eight hours after their purification start, we counted the chains present at the surface of the CD4 T lymphocytes by extrapolation of the autocorrelation function at the origin (Equation 5) in the observed surface ω02. Total concentrations of both chains at the surface correspond to [IL-7Rα] = 108 pmol/m2 and [γc] = 12.3 pmol/m2. The concentration of the complex was extrapolated from the cross-correlated function: [IL-7Rα·γc] = 10.0 pmol/m2. As we had now determined the concentration of different molecular species, we were able to evaluate the dissociation constant at apparent equilibrium: Kd = 24.3 pmol/m2. About 80.2% of γc were assembled in IL-7Rα·γc complexes, whereas only 10.1% of IL-7Rα were engaged in heterodimers. We checked formation of the IL-7Rα homodimer by labeling IL-7Rα with anti-IL-7Rα mAbb coupled to SA488 (50%) and SA633 (50%). From cross-correlations that accounted for half the IL-7Rα·IL-7Rα homodimers (50% SA488/SA633 versus 25% SA488/SA488 and 25% SA633/SA633) we measured the Kd = 336 pmol/m2. In all, 17.4% of IL-7Rα were engaged in homodimers and were then unavailable for γc-binding. The corrected Kd for IL-7Rα·γc dissociation was therefore 19.6 pmol/m2. IL-7Rα affinity for itself is thus 17-fold weaker than for γc.

FIGURE 1.

FCS analysis of IL-7R chain diffusion. Normalized ACF G(τ) were plotted from 10 averaged acquisitions versus diffusion times τD (log scale in seconds) in panel E for rhodamine-6G (a), SA488 (b), and anti-IL-7Rα mAbb·SA488 (c) in colorless completed RPMI medium fitted as the three-dimensional diffusion particle according to Equation 1. ACF of γc (d) and IL-7Rα (e) were labeled with their respective mAbb·SA488, IL-7Rα·mAbb·SA488 in the presence of unlabeled IL-7 (g) was plotted as mixed two-/three-dimensional diffusion particles at the surface of CD4 T cells analyzed at ω02 = 70 × 103 nm2 and fitted with Equation 4. Normalized CCF were also plotted from 10 averaged acquisitions for IL-7Rα·mAbb·SA488·γc·mAbb·SA633 (f) and IL-7Rα·mAbb·SA488·γc·IL-7b·SA633 (h) considered as two-dimensional diffusion particles at the surface of CD4 T cells. Residuals from fitting with different mathematical diffusion models are given, for example, in panels A-C for IL-7Rα·mAbb·SA488 after ACF fitting with models accounting for one two-dimensional component (A, Equation 3), one two-dimensional and one three-dimensional (B, Equation 4), and two two-dimensional and one thre-dimensional (C, Equation 4). Residuals are also given in panel D for IL-7Rα·mAbb·SA488·γc·IL-7b·SA633 after CCF fitting with models accounting for one two-dimensional component (A, Equation 8). Dashed lines indicates half-height cross-correlation function inflection points of single component diffusion. Arrows indicate diffusion times for slow and fast diffusing particles. Six ACF are plotted at increasing ω02 values for IL-7Rα·mAbb·SA488 (panel F) and six CCF for IL-7Rα·mAbb·SA488·γc·IL-7b·SA633 (panel G). Corresponding curves in e and h plotted in panel E acquired at ω02 = 70 × 103 nm2 are shown with arrows. Corresponding τD values extracted from their fitting were used to build diffusion plots (Equation 2) as shown in Figs. 2 and 3.

FIGURE 2.

Receptor chain diffusion and assembly at the surface of living CD4 T lymphocytes. A, IL-7-free IL-7Rα, γc, and IL-7Rα·γc diffusion analysis by FCS/FCCS. The following diffusion times τD (in 10−3 s) acquired in the absence of IL-7 are plotted versus the surface area ω2 intercepted by the confocal volume (in 103 nm2) accordingly to Equation 2: IL-7Rα·anti-IL-7Rα·mAbb·SA488 ACF (○), γc·anti-γc·mAbb·SA633 ACF (▵), IL-7Rα·anti-IL-7Rα·mAbb·SA488 with γc·anti-γc·mAbb·SA633 CCF (♦). Slopes of the linear regression give effective diffusion rates Deff and intercepts at the y axis extrapolate confinement times τ0. B, IL-7-bound IL-7Rα, γc, and IL-7Rα·γc diffusion analysis by FCS·FCCS. The following diffusion times τD (in 10−3 s) in the presence of IL-7b·SA633 are plotted versus the surface area ω2 intercepted by the confocal volume (in 103 nm2): ACF of IL-7Rα·anti-IL-7Rα·mAbb·SA488 in the absence of IL-7 (○), ACF of IL-7Rα·anti-IL-7Rα·mAbb·SA488 in the presence of IL-7 (□), CCF of IL-7Rα·anti-IL-7Rα·mAbb·SA488 with IL-7b·SA633 (■). Slopes of the linear regression give Deff and intercepts at the y axis extrapolate τ0. Error bars give S.E.

Interestingly, IL-7 binding affects its receptor diffusion as shown with the longer diffusion times at the inflection point in Fig. 1E, curve f, by comparison with curve e for the same observed membrane surface area. IL-7 slows down 2.6-fold the IL-7Rα diffusion rate, as shown in Fig. 2B, Deff = 0.065 ± 0.014 μm2/s. The effect was even more obvious when we observed the complex by analyzing the cross-correlation between IL-7Rα·mAbb·SA488 diffusion and the diffusion of biotinylated IL-7 labeled with SA633 (IL-7b·SA633) (Fig. 1E, curve h, and G): Deff = 0.024 ± 0.0038 μm2/s, 7.2-fold slower than α·γc and 9-fold than α (Fig. 2B). As can be seen in Fig. 2, A and B, extrapolation of the IL-7Rα·γc linear regression crosses the y axis below the origin before (τ0 = −62 ± 9.8 ms) and after IL-7 binding (τ0 = −242 ± 38 ms). τ0 was described by Marguet and colleagues (25) as the confinement time assessing the retention duration of particles by the cytoskeleton meshwork fencing reduced area below the plasma membrane. τ0 increases 4-fold after IL-7-binding, suggesting not only collision of the receptor complex but also tighter interactions with cytoskeleton components.

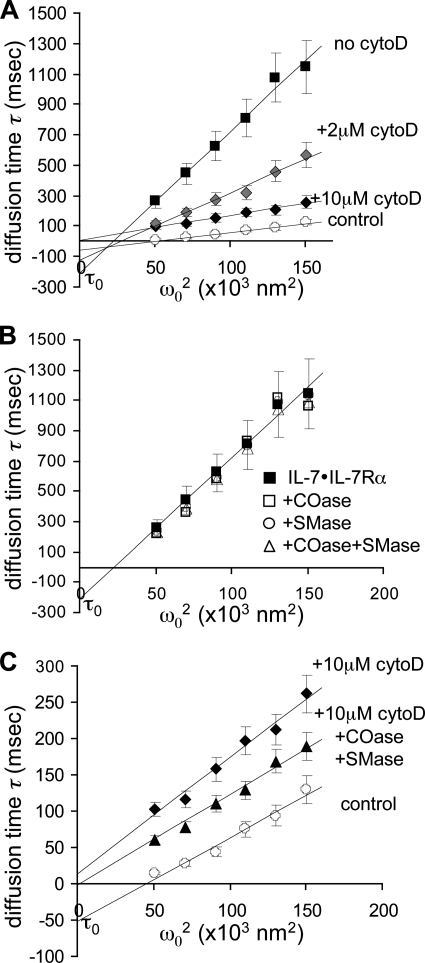

Mechanism Involved in IL-7R Compartmentalization

IL-7 binding slowed down the diffusion rate of the receptor and increased its confinement time. In attempts to demonstrate that the cytoskeleton is involved in confinement time and the diffusion brake, we used a drug that depolymerizes actin fibers: CytD. Fig. 3A shows that CytD did not significantly affect the diffusion rates of IL-7-free receptors: Deff = 0.227 ± 0.030 μm2/s, τ0 = +2.4 ± 0.4 ms for 10 mm CytD compared with Deff = 0.173 μm2/s, τ0 = −62 ms without CytD. By contrast, a CytD dose-dependent increase of IL-7R diffusion was noted in the presence of IL-7: Deff = 0.210 ± 0.033 μm2/s, τ0 = +8.1 ± 1.3 ms for 10 mm CytD compared with 0.024 μm2/s, τ0 = −242 ms without CytD. This 9-fold increase suggests that the IL-7·IL-7R complex is no longer interacting with the cytoskeleton meshwork and is released from its confinement state. Sphingomyelinase and cholesterol oxidase, which inhibit lipid raft formation, had no significant effect on receptor slowing in the presence of its ligand (Fig. 3B): Deff = 0.026 ± 0.0036 μm2/s, τ0 = −182 ± 26 ms. However, sphingomyelinase and cholesterase oxidase did have a noticeable effect after CytD treatment as the IL-7·IL-7R complex was once more freely diffused, as observed for the ligand-free receptor: Deff = 0.349 ± 0.047 μm2/s, τ0 = +11.4 ± 1.7 ms (Fig. 3C).

FIGURE 3.

Effect of the cytoskeleton and lipid rafts on IL-7R diffusion. A, IL-7R compartmentalization is released after addition of CytD. The following diffusion times, τD (in 10−3 s), in the presence of IL-7-biotin·streptavidin-A633 are plotted versus the surface area ω2 intercepted by the confocal volume (in 103 nm2): ACF of IL-7Rα·mAbb·SA488 in the absence of IL-7 (○), CCF of IL-7Rα·mAbb·SA488 with IL-7b·SA633 without CytD (■), in the presence of 2 (gray diamond) and 10 μm CytD (♦). Slopes of the linear regression give effective diffusion rates, Deff, and intercepts at the y axis extrapolate confinement time, τ0. B, IL-7R is not affected by the addition of cholesterase oxidase (COase) (1 unit/ml) and sphingomyelinase (Smase) (0.1 unit/ml). The following diffusion times, τD (in 10−3 s), are plotted versus the surface area ω02 intercepted by the confocal volume (in 103 nm2): CCF of IL-7Rα·mAbb·SA488 with IL-7b·SA633 before (■) and after treatment with cholesterase oxidase (1 unit/ml) (□) and sphingomyelinase (0.1 units/ml) (○) or both (▵). C, IL-7R is freed by cholesterase oxidase (1 unit/ml) and sphingomyelinase (0.1 unit/ml) only after CytD treatment. The following diffusion times, τD (in 10−3 s), are plotted versus the surface area ω02 intercepted by the confocal volume (in 103 nm2): ACF of IL-7Rα·mAbb·SA488 in the absence of IL-7 (○), CCF of IL-7Rα·mAbb·SA488 with IL-7b·SA633 in the presence of 10 μm CytD (♦), 10 μm CytD with cholesterase oxidase (1 unit/ml) and sphingomyelinase (0.1 unit/ml) (▴). Slopes of the linear regression give Deff and intercepts at the y axis extrapolate τ0. Error bars give S.E.

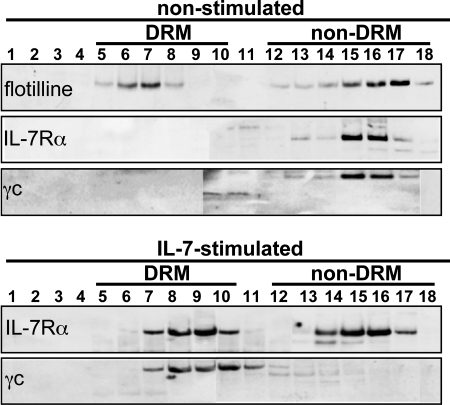

IL-7·IL-7R Is Extracted into Detergent-resistant Microdomains when Activated

As sphingomyelinase and cholesterase oxidase affect the IL-7·IL-7R diffusion rate in the presence of CytD, this suggests that as well as interacting with the cytoskeleton, the receptor is also interacting with lipid rafts or proteins embedded in these rafts. To investigate receptor chain partition inside and outside lipid rafts upon ligand binding, we extracted DRM by ultracentrifugation in sucrose gradients. We lysed the CD4 T cells with 0.5% Triton X-100, removed by centrifugation unlysed cells and organelles, and separated the insoluble and soluble membrane fractions by ultracentrifugation on a sucrose viscosity gradient according to their sedimentation velocities. By using flottilin-1 as a fraction marker of DRM microdomains, we demonstrated, in the Western blot shown in Fig. 4, that IL-7Rα and the γc chain are located in Triton-solubilized fractions 13–17 before IL-7 binding, and in insoluble fractions 6–10 after IL-7 binding. This appearance of IL-7R chains in DRM domains suggests that the receptors are driven into lipid rafts upon IL-7 binding, or that lipid rafts are formed around the cytokine-bound receptor.

FIGURE 4.

IL-7Rα and γc are found in DRM after IL-7 stimulation of CD4 T cells. CD4 T lymphocyte lysates were loaded on a 5–40% sucrose gradient and divided into 18 fractions after 16 h of centrifugation at 50 krpm at 4 °C. Fractions: 1 left, tube top = 5%; 18 right, tube bottom = 40%) were loaded on SDS-PAGE (7% acrylamide-bisacrylamide). Flottilin, IL-7Rα, and γc were located in the membrane fractions by immunoblotting. Fractions corresponding to DRM are indicated above the membrane strip according to flottilin distribution.

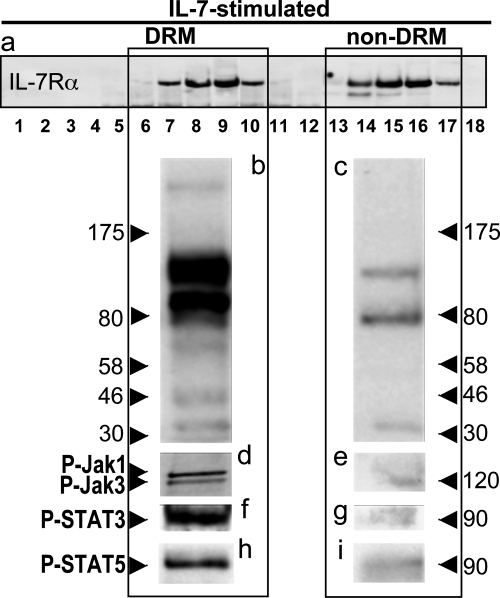

To characterize the role played by receptor partition in signaling, we checked whether Jak/STAT phosphorylation was associated with receptors inside or outside DRM. To do this, we immunoprecipitated proteins with anti-IL-7Rα: 1) from pooled fractions 6–10 (DRM), or 2) pooled fractions 13–17 (soluble fraction of the membrane) of the IL-7-stimulated cell lysate samples. Protein phosphorylation on the Western blots was detected using anti-Tyr(P). Fig. 5 shows that proteins with IL-7-induced phosphorylation of Tyr were mainly located inside DRM. More specifically, phosphorylated Jak1, Jak3, STAT3, and STAT5 after IL-7 activation were found in DRM, with barely traces outside.

FIGURE 5.

Phosphorylated Jaks and STAT5 are found mainly in DRM after IL-7 stimulation of CD4 T cells. Materials were prepared as described in the legend to Fig. 4. a, after centrifugation, fractions 6 to 10 were pooled to provide a “DRM” sample and fractions 13 to 17 were pooled to form a “solubilized” sample. Both samples were loaded on SDS-PAGE (7% acrylamide-bisacrylamide). Tyr-phosphorylated proteins Tyr(P) (b and c), pJak (d and e), pSTAT3 (f and g), and pSTAT5 (h and i) were revealed by immunoblotting.

Proteins Immunoprecipitated with IL-7Rα before and after IL-7 Binding

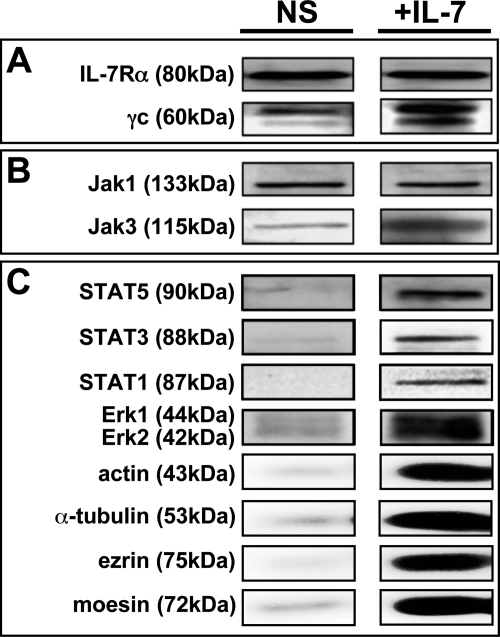

It was clear that some proteins are carried by IL-7R before and after IL-7 binding, and their interactions are preserved in Triton cell-lysis buffer. We therefore investigated the protein cortege pulled down with the receptor by immunoprecipitation using anti-IL-7Rα from lysed CD4 T lymphocytes. The first step consisted in checking the presence of proteins involved in IL-7R signaling that were separated from the IP complex by heat denaturation in SDS and migration on one-dimensional SDS-PAGE. Protein-specific Western blots are shown in Fig. 6. IL-7Rα was detected as a control. γc was found in cells activated by IL-7 and to a lesser extent in resting cells. This demonstrated that γc interacts spontaneously with IL-7Rα at the surface of resting CD4 T lymphocytes prior to becoming embedded in lipid rafts. IL-7 stabilizes the IL-7Rα·γc interaction as suggested by the darker band of pulled down γc. The same amount of Jak1 was carried out before and after IL-7 binding, and this was consistent with the constitutive binding of Jak1 onto the IL-7Rα cytoplasmic domain. The Jak3 band was darker in the activated signaling complexes and its quantity correlated to the amount of γc. Jak1 and Jak3 are resident proteins on IL-7R chains and some complexes were fully preassociated prior to IL-7 binding. As expected, STAT1, STAT3, and STAT5 were pulled down only after IL-7 binding as STAT recruitment after IL-7-induced phosphorylation of the IL-7Rα cytoplasmic domain on Tyr456 provides a STAT binding site. Proteins ERK1 and ERK2 were also clearly recruited on the signaling complex after IL-7 binding to IL-7R. As IL-7R interaction with cytoskeleton was expected, recruitment of actin (microfilament), α-tubulin (microtubule), ezrin and moesin (FERM linking rafted proteins with cytoskeleton) were tested and the presence of all four proteins was confirmed after IL-7 activation (Fig. 6).

FIGURE 6.

Proteins immunoprecipited with IL-7Rα before and after IL-7 stimulation of CD4 T cells. Proteins were immunoprecipitated with anti-IL-7Rα from CD4 T lymphocyte lysate and separated on SDS-PAGE (7% acrylamide-bisacrylamide). Corresponding bands were cut out of images of specific immunoblots from non-stimulated (NS) and IL-7-stimulated (+IL-7) cells. A, receptor chains; B, “resident” protein selection; C, “IL-7-recruited” protein selection.

Signaling Complex Analyzed by Two-dimensional PAGE and MALDI-TOF/TOF

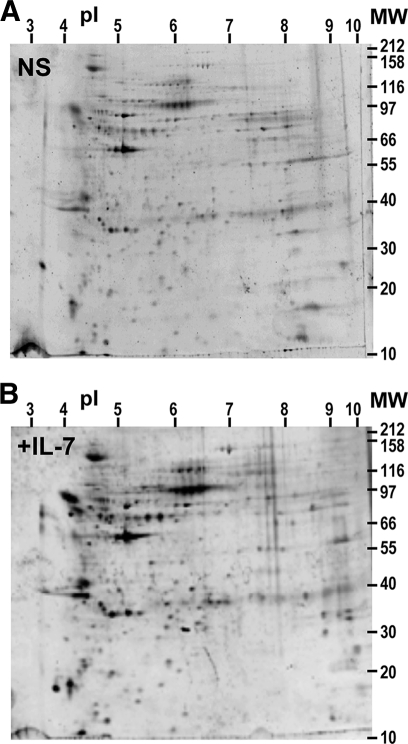

The composition of the signaling complex evidently formed after IL-7 binding was investigated by separating the IP components on two-dimensional SDS-PAGE and Sypro-Ruby staining. Fig. 7 shows a representative pair of two-dimensional PAGEs from non-stimulated (NS) and activated (+IL-7) cells. Eight gel pairs were analyzed from non-stimulated and IL-7-stimulated purified CD4 T cells from 8 healthy human blood donors. The intensity of 314 spots was measured and calibrated per gel, then aligned between gels to compare their Sypro-staining intensity. In all, 249 reproducible spots found in at least 6 of the 8 gels were plugged from two-dimensional PAGE. Proteins were digested in trypsin, eluted, and analyzed by combined MS and MS/MS from MALDI-TOF/TOF procedures. The 109 proteins identified from at least 5 sequenced peptides specific to the protein sequence in the Uniprot data base are detailed in supplemental Table S1. They were then sorted according to the increase in spot staining intensity after IL-7 binding. 78 proteins were increased by a factor of 4 or more, whereas 26 proteins were increased by a factor from 2 to 3.9. We also noted that four proteins were decreased after IL-7 binding.

FIGURE 7.

Two-dimensional PAGE analysis of proteins immunoprecipitated with IL-7Rα before and after IL-7 stimulation of CD4 T cells. Proteins were immunoprecipitated with anti-IL-7Rα from CD4 T lymphocyte lysate and separated on two-dimensional PAGE (pH 3–10 and 12% acrylamide-bisacrylamide). Gels were stained with Sypro-Ruby: A, top, non-stimulated cells (NS); B, bottom, IL-7-stimulated cells (IL-7). pH and molecular weight scales are displayed.

Among the 109 proteins identified, Table 1 lists the 78 proteins recruited by the IL-7R signaling complex after IL-7 binding, i.e. that were at least 4-fold more abundant in the immunoprecipitated complex after IL-7 binding than before. Two-thirds of the pulled down proteins (48/78) are involved in the cytoskeleton (42/78) or have been described as associated with lipid rafts (6/78). None of the proteins in the IL-7R signalosome and none of those found by Western blotting (Fig. 6) in the same IP complex preparation were among the proteins identified until the cut off was lowered to select peptides with m/z peaks bellow the top 15 most intense. The concentration of abundant proteins overwhelmed those present at low levels. Interestingly, the cytoskeleton group included actin and its binding proteins that regulate filament assembly (gelsolin, cofilin, profilin, actin capping proteins, and coactosin) and membrane filament anchors or intermediate linkers (vinculin, zyxin, ezrin, and moesin), proteins involved in microfilament polymerization (HSP70), proteins involved in calcium-induced recruitment by the cytoskeleton (calmodulin, calreticulin, and sorcin), and actin-binding linkers and carriers (myosin, tropomyosin, plastin-2, and derbrin-like). Microtubule subunits (α- and β-tubulin) were abundantly recruited upon IL-7 binding. We also found proteins known for their embedding in lipid rafts (integrin) and their interactions with the cytoskeleton through vinculin, ezrin, and moesin. Plekstrin, which interacts with phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate in lipid rafts was also found. Certain recruited proteins are mainly involved in folding/unfolding and degradation processes (HSP, proteasome activator, thioredoxine, glutathione transferase, and disulfide isomerase) and oxidation-reduction reactions (peroxiredoxin and superoxide dismutase) and might be carried with the cytoskeleton.

TABLE 1.

Proteins identified by MALDI-TOF/MS/MS at least 4-fold more abundant among those immunoprecipitated with IL-7Rα from CD4 T cell lysates when cells were stimulated for 5 min with 2 nm IL-7

a CD4 lymphocytes were stimulated or not by IL-7 and their lysates were immunoprecipitated by anti-IL-7Rα mAb. Immunoprecipitated proteins were separated by two-dimensional-PAGE and SYPRO-stained spots were analyzed for their intensity with SameSpot software and compared between stimulated and non-stimulated conditions over the CD4 T cell lysates from eight blood donors. Reproducible spots were analyzed by MALDI-TOF/MS/MS. The 78 proteins were selected according to the ratio >= 4 from the full table (109 proteins) provided as supplemental Table S1 and divided into four classes. Numbers of classified proteins are bracketed.

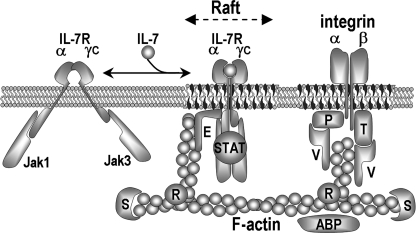

Fig. 8 summarizes the IL-7-driven compartmentalization steps according to our IP analysis before (Fig. 7A) and after (Fig. 7B) IL-7 binding. Cytokine-free IL-7R diffuses freely with a reduced carriage (Jaks) at the surface of CD4 T lymphocytes, then upon cytokine binding IL-7R is recruited by the cytoskeleton and interacts with other raft-embedded proteins.

FIGURE 8.

Sketch views of the IL-7R-signaling complex assembly upon IL-7 binding. Left (NS conditions), the IL-7-free heterodimer IL-7Rα·γc is embedded in the lipid bilayer out of rafts; Jak1 and Jak3 are constitutively bound to their cognate cytoplasmic receptor chains. Right (+IL-7 conditions), the complex IL-7·IL-7Rα·γc is embedded in the lipid raft. STAT is bound to IL-7Rα·γc·Jak1·Jak3. FERM proteins (E) connect IL-7Rα to F-actin. Integrin chains are linked to F-actin through praxillin (P) or talin (T) complexed to vinculin (V) and Arp2-3 (42). ABP represents actin-binding proteins, S symbolizes proteins inhibiting F-actin elongation, and R represents proteins involved in filament ramification. Tubulin assemblies and proteins unrelated to cytoskeleton are not represented.

DISCUSSION

IL-7 induces a variety of responses ex vivo in CD4 T lymphocytes, e.g. cell activation, survival, and proliferation, mainly through γc-signaling Jak/STAT, AKT/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, and mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways. Signaling proteins involved have been mainly identified through their cytokine-induced phosphorylation and have been functionally grouped together in the IL-7R “signalosome” (4, 5, 23). However, the early IL-7 response has yet to be described at the molecular level of its receptor and interacting proteins that form a physical entity and are considered the “signaling complex.” The mechanism involved in assembly of the receptor itself is unknown and the protein involved in signaling transduction is known for phosphorylated ones but very little is known concerning the number and function of the “dark” proteins involved. New time-resolved microimaging tools have now enabled us to analyze receptor assembly on living primary cells revealing the story board of the early receptor response for a few entities at a time, and proteomics approaches the sum of the composition of these complexes.

In this work, we demonstrate for the first time that IL-7Rα and γc spontaneously form heterodimers (1:1 stoichiometry) at the surface of living human CD4 T cells even in the absence of IL-7. IL-7Rα is highly expressed in the resting CD4 T cells of healthy humans (108 pmol/m2), whereas γc (12 pmol/m2) is present only at low concentrations and thus restricts heterodimer formation (10 pmol/m2). The heterodimer was seen to have a dissociation constant Kd of 19 pmol/m2. The affinity is greater than the γc chain concentration and explains why 80% of γc is found in the bound state in cultures of living cells. As already noted for soluble fragments (21), this very high affinity suggests that the γc chain is titrated by abundant IL-7Rα at the cell surface. We also observed that IL-7Rα forms homodimers, as previously suggested (21, 23) and demonstrated for homolog IL-2Rβ (26–28). We confirmed that these homodimers assemble spontaneously in the absence of IL-7 with 1:1 stoichiometry, and noted that the affinity of IL-7Rα is 17-fold greater for γc than for itself, meaning that formation of the heterodimer is largely favored and does not limit γc binding. Both the heterodimer and the homodimer coexist in resting cells.

IL-7 binding to its receptor is followed by receptor complex compartmentalization. In our studies, the binding of IL-7 to its receptor almost halted its lateral diffusion and, in accordance with the criteria established by Marguet and colleagues (25, 29), receptor retention time in the cytoskeleton meshwork was increased at least 4-fold after IL-7 binding, suggesting not only collision of the receptor complex but also tighter interactions with cytoskeleton components in living cell cultures at 37 °C. This was first demonstrated by showing that the interaction was lost when IL-7-activated cells were treated with a cytoskeleton polymerization inhibitor (cytochalasin D). Our subsequent analysis by two-dimensional PAGE further supported these results as discussed below. IL-7 binding to its receptor also altered its distribution in detergent-resistant membrane nanodomains. This observation suggests that migration was taking place into lipid rafts or that lipid rafts were being formed around the receptor. We have therefore for the first time shown that phosphorylated Jak and STAT5 are associated with raft-embedded receptors. Interestingly, although lipid raft formation was not dependent on the cytoskeleton meshwork, receptor dissociation from the lipid rafts was dependent on depolymerization of actin microfilaments.

Our studies of IP complex composition showed that three categories of proteins were pulled down with anti-IL-7Rα. First, we found both receptor chains themselves, IL-7Rα and γc, moderately associated in the absence of cytokine and then stabilized in the presence of cytokine. Second, some proteins were bound to receptor chains independently of the presence of cytokine, e.g. Jaks. These resident proteins were pulled down before and after IL-7 binding. Third, some proteins were recruited transiently upon cytokine binding and were then phosphorylated and released, for instance, STAT and ERK. These recruited proteins were pulled down only after IL-7 binding. Many proteins involved in IL-7 signaling pathways were not found in the MS protein list according to the stringent selection criteria used for protein identification: at least 5 of the 15 most intense m/z peaks yielded a positive sequence match with the MS/MS analysis. However, the presence of several proteins was validated by Western blotting and many were found from MS lists using less stringent criteria. To date, among cytokine receptors only, the signaling complex associated with mouse IL-1R has been studied by proteomics (30). Interferon, prolactin, growth hormone, and erythropoietin are among those best resolved for their assembly at the molecular level, and although their signaling complexes have not yet been elucidated, pioneer works on epidermal growth factor receptor and prolactin receptor have suggested that machinery carried by the cytoskeleton might be involved (31, 32).

In our work, we noted that two-thirds of the proteins recruited upon IL-7 binding have already been described as part of the cytoskeleton or are associated with lipid rafts. Cytoskeleton-associated proteins identified included microfilament and microtubule compounds, proteins regulating their polymerization and depolymerization, and intermediates such as myosin and tropomyosin. We also found proteins involved in cytoskeleton connection to the membrane (ezrin, moesin, and vinculin). These FERM proteins (for 4.1 protein, ezrin, radixin, and moesin) regulate the anchorage of plasma membrane proteins to actin cytoskeleton. These proteins have already been described in the regulation of signal transduction pathways (33, 34). Ezrin and moesin are well expressed in T cells, whereas radixin is low. FERM proteins interact with positively charged amino acid clusters in the juxtamembrane region of proteins embedded in lipid rafts. There is a putative FERM-binding domain at the juxtamembrane sequence of the cytoplasmic domain of IL-7Rα, characterized by several basic residues (265KKRIKPIVWPSLPDHKKTLEHLCKKPRK292) in the extension of the helical transmembrane domain (240–264) (35) as also found in IL-2Rβ (266NCRNTGPWLKKVLKCNTPDPSK287) but not in γc. This FERM-binding domain could be involved in receptor recruitment of FERM proteins, anchoring the complex to the cytoskeleton. Full-length FERM proteins show a low level of binding activity to both membrane and actin. These inactive states are believed to be expressed by a masking mechanism in which the FERM domain binds the C-terminal half to suppress the actin filament and membrane binding activities (36–39). Biochemical studies have shown that phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate also binds FERM domains and stimulates the binding of FERM proteins to their targets (39, 40). Interestingly, the FERM domains bind the Rho-specific GDP-dissociation inhibitor (RhoGDI) found among IL-7R-recruited proteins and accelerate the release of Rho to activate Rho-dependent processes (39, 41), suggesting involvement by the Rho signaling pathway.

Integrin αIIb receptor chain is among the most IL-7R-recruited proteins upon IL-7 binding. This receptor chain, which interacts with the extracellular matrix (fibronectin and fibrinogen γ), has been described as embedded in lipid rafts (42). Vinculin, which is also among the highly recruited proteins, has been described as interacting with integrin through the talin intermediate. Talin is very heavy (270 kDa) and was not selected from our 12% acrylamide SDS-PAGE. Vinculin links the integrin receptor-talin complex with contribution of actin-related protein 2–3 (ARP2–3) to actin filaments. The functional role played by talin/vinculin/ARP2–3 in T cells has not been assessed but might be involved in linking de novo actin polymerization to integrin activation.

Although lipid rafts have been implicated in a number of cellular functions, their role in lymphocytes has so far been studied mainly in the context of immunoreceptor signaling and is now accepted that lipid rafts are dynamic platforms in T cells where proteins implicated in the TCR signaling cascade are transiently recruited following receptor engagement. Recent data have also shown that the TCR signaling-initiation machinery is actually preassembled in lipid rafts (42). Protein association with lipid rafts is likely to be facilitated by raft coalescence following TCR triggering, a process promoted by cortical actin reorganization and enhanced by the engagement of co-stimulatory receptors such as CD28 (42) and clustered at the immunological synapse. No such coalescence is observed during formation of the IL-7R signaling complex: its distribution looked isotrope.

This work describes the early steps in IL-7R responses to its cognate cytokine at the surface of human resting primary CD4 T lymphocytes. γc chains are weakly expressed at the cell surface, whereas IL-7Rα are abundant. Most of the γc chains are associated with IL-7Rα and form high affinity active receptors that diffuse laterally out of lipid rafts at the cell surface. When IL-7 binds to its preformed receptor, this drives it into lipid rafts or the lipid rafts are formed around the receptor. The IL-7·IL-7R complex then recruits proteins to build the signaling complex, e.g. FERM proteins that anchor the rafted receptor and its carriage to the cytoskeleton meshwork and halt its diffusion as summarized in Fig. 8. Lipid rafts are rich in cholesterol and sphingomyelin, which increase membrane thickness and hold the long single transmembrane helical domain straight, thus favoring the juxtaposition of the cytoplasmic domains. The H-bond network between cholesterol and sphingomyelin reduces the lateral diffusion of lipids and embedded proteins. We hypothesize that viscous rafts slow down the dissociation process between receptor subunits and thereby prolong IL-7·IL-7R association. Cytokine residency time is crucial to amplify the response translated by STAT phosphorylation turnover (43). The cytoskeleton might provide a scaffold for uploading and downloading of signaling proteins, their storage, and might involve large machineries to dispatch signaling products to their targets.

In more general terms, our functional proteomics approach has led to the discovery of mechanisms linking lipid rafts and the cytoskeleton with a number of additional functions involving cell membranes and cytoplasmic proteins in T cells. Our findings have thrown light on an unexpected dynamic pattern of interactions between lipid rafts and not only proteins participating in the IL-7R signaling cascade, but also a wide array of proteins associated directly or indirectly with the plasma membrane and intracellular membranes, and implicated in a variety of cell functions. Although the biological significance of the association between lipid rafts, the cytoskeleton, and the various proteins identified requires clarification, this study provides insight into the profound and far reaching changes induced in a cell by the triggering of surface receptors.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Andres Alcover and Dr. Rémi Lasserre (Institut Pasteur) for helpful discussion. We thank Pascal Roux (Plate-Forme d'Imagerie Dynamique, Institut Pasteur) for expertise and technical help in confocal microscopy, Dr. Klaus Weisshart and Dr. Bernhard Götze (Zeiss) for FCS expert advice, Christine Laurent (IP) for expert advice in two-dimensional PAGE, and Philippe Bogart (Non-Linear) for assistance in gel analysis. We thank Dr. Mark Jones for text editing (Transcriptum). We extend our gratitude to the volunteer blood donors and staff at the Etablissement Français du Sang (Centre Cabanel-Paris).

This work was supported in part by the Institut Pasteur.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Fig. S1 and Table S1.

- IL

- interleukin

- ACF

- autocorrelated function

- CCF

- cross-correlated function

- DRM

- detergent-resistant membrane domain

- FCS

- fluorescence autocorrelated spectroscopy

- FCCS

- fluorescence cross-correlated spectroscopy

- IP

- immunoprecipitation

- Jak

- Janus kinase

- mAbb

- biotinylated monoclonal antibody

- pAb

- polyclonal antibody

- MS

- mass spectrometry

- SA488/633

- streptavidin-Alexa Fluor 488/633

- STAT

- signal transducer and activator of transcription

- TCR

- T cell receptor

- ERK

- extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- MALDI-TOF

- matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ma A., Koka R., Burkett P. (2006) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 24, 657–679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fry T. J., Mackall C. L. (2005) J. Immunol. 174, 6571–6576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee S. K., Surh C. D. (2005) Immunol. Rev. 208, 169–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palmer M. J., Mahajan V. S., Trajman L. C., Irvine D. J., Lauffenburger D. A., Chen J. (2008) Cell Mol. Immunol. 5, 79–89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rochman Y., Spolski R., Leonard W. J. (2009) Nat. Rev. Immunol. 9, 480–490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goodwin R. G., Lupton S., Schmierer A., Hjerrild K. J., Jerzy R., Clevenger W., Gillis S., Cosman D., Namen A. E. (1989) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 86, 302–306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bolotin E., Annett G., Parkman R., Weinberg K. (1999) Bone Marrow Transplant. 23, 783–788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Napolitano L. A., Grant R. M., Deeks S. G., Schmidt D., De Rosa S. C., Herzenberg L. A., Herndier B. G., Andersson J., McCune J. M. (2001) Nat. Med. 7, 73–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fry T. J., Mackall C. L. (2001) Trends Immunol. 22, 564–571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sportès C., Hakim F. T., Memon S. A., Zhang H., Chua K. S., Brown M. R., Fleisher T. A., Krumlauf M. C., Babb R. R., Chow C. K., Fry T. J., Engels J., Buffet R., Morre M., Amato R. J., Venzon D. J., Korngold R., Pecora A., Gress R. E., Mackall C. L. (2008) J. Exp. Med. 205, 1701–1714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiang Q., Li W. Q., Hofmeister R. R., Young H. A., Hodge D. R., Keller J. R., Khaled A. R., Durum S. K. (2004) Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 6501–6513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khaled A. R., Li W. Q., Huang J., Fry T. J., Khaled A. S., Mackall C. L., Muegge K., Young H. A., Durum S. K. (2002) Immunity 17, 561–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maraskovsky E., O'Reilly L. A., Teepe M., Corcoran L. M., Peschon J. J., Strasser A. (1997) Cell 89, 1011–1019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goodwin R. G., Friend D., Ziegler S. F., Jerzy R., Falk B. A., Gimpel S., Cosman D., Dower S. K., March C. J., Namen A. E., Park L. S. (1990) Cell 60, 941–951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pandey A., Ozaki K., Baumann H., Levin S. D., Puel A., Farr A. G., Ziegler S. F., Leonard W. J., Lodish H. F. (2000) Nat. Immunol. 1, 59–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park L. S., Martin U., Garka K., Gliniak B., Di Santo J. P., Muller W., Largaespada D. A., Copeland N. G., Jenkins N. A., Farr A. G., Ziegler S. F., Morrissey P. J., Paxton R., Sims J. E. (2000) J. Exp. Med. 192, 659–670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alves N. L., van Leeuwen E. M., Derks I. A., van Lier R. A. (2008) J. Immunol. 180, 5201–5210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Colle J. H., Moreau J. L., Fontanet A., Lambotte O., Delfraissy J. F., Thèze J. (2007) AIDS 21, 101–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Colle J. H., Moreau J. L., Fontanet A., Lambotte O., Joussemet M., Delfraissy J. F., Thèze J. (2006) Clin. Exp. Immunol. 143, 398–403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park J. H., Yu Q., Erman B., Appelbaum J. S., Montoya-Durango D., Grimes H. L., Singer A. (2004) Immunity 21, 289–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rose T., Lambotte O., Pallier C., Delfraissy J. F., Colle J. H. (2009) J. Immunol. 182, 7389–7397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McElroy C. A., Dohm J. A., Walsh S. T. (2009) Structure 17, 54–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leonard W. J., Imada K., Nakajima H., Puel A., Soldaini E., John S. (1999) Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 64, 417–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bacia K., Schwille P. (2007) Nat. Protoc. 2, 2842–2856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lenne P. F., Wawrezinieck L., Conchonaud F., Wurtz O., Boned A., Guo X. J., Rigneault H., He H. T., Marguet D. (2006) EMBO J. 25, 3245–3256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eckenberg R., Rose T., Moreau J. L., Weil R., Gesbert F., Dubois S., Tello D., Bossus M., Gras H., Tartar A., Bertoglio J., Chouaïb S., Goldberg M., Jacques Y., Alzari P. M., Thèze J. (2000) J. Exp. Med. 191, 529–540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rose T., Moreau J. L., Eckenberg R., Thèze J. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 22868–22876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pillet A. H., Juffroy O., Mazard-Pasquier V., Moreau J. L., Gesbert F., Chastagner P., Colle J. H., Thèze J., Rose T. (2008) Eur. Cytokine Netw. 19, 49–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lasserre R., Guo X. J., Conchonaud F., Hamon Y., Hawchar O., Bernard A. M., Soudja S. M., Lenne P. F., Rigneault H., Olive D., Bismuth G., Nunès J. A., Payrastre B., Marguet D., He H. T. (2008) Nat. Chem. Biol. 4, 538–547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brikos C., Wait R., Begum S., O'Neill L. A., Saklatvala J. (2007) Mol. Cell. Proteomics 6, 1551–1559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lopez-Perez M., Salazar E. P. (2006) Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 38, 1716–1728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zoubiane G. S., Valentijn A., Lowe E. T., Akhtar N., Bagley S., Gilmore A. P., Streuli C. H. (2004) J. Cell Sci. 117, 271–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bretscher A., Edwards K., Fehon R. G. (2002) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3, 586–599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fiévet B., Louvard D., Arpin M. (2007) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1773, 653–660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Girault J. A., Labesse G., Mornon J. P., Callebaut I. (1999) Trends Biochem. Sci. 24, 54–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Andréoli C., Martin M., Le Borgne R., Reggio H., Mangeat P. (1994) J. Cell Sci. 107, 2509–2521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thuillier L., Hivroz C., Fagard R., Andreoli C., Mangeat P. (1994) Cell. Immunol. 156, 322–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gary R., Bretscher A. (1995) Mol. Biol. Cell 6, 1061–1075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hirao M., Sato N., Kondo T., Yonemura S., Monden M., Sasaki T., Takai Y., Tsukita S., Tsukita S. (1996) J. Cell Biol. 135, 37–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Niggli V., Andréoli C., Roy C., Mangeat P. (1995) FEBS Lett. 376, 172–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Takahashi K., Sasaki T., Mammoto A., Takaishi K., Kameyama T., Tsukita S., Takai Y. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 23371–23375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chichili G. R., Rodgers W. (2009) Cell Mol. Life Sci. 66, 2319–2328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stroud R. M., Wells J. A. (2004) Sci. STKE 2004, re7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]