Abstract

Purpose

Tandem repeat (TR) is the key epitope of mucin 1 (MUC1) for inducing cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) to kill the tumor cells specifically. This study aimed to construct a new recombinant DNA vaccine based on single TR and to investigate the induced immune responses in mice.

Materials and methods

After the synthesis of a recombinant human TR(rhTR)and the construction of the recombinant plasmid pcDNA3.1-TR/Myc-his (+) A (pTR plasmid), C57BL/6 (H-2b) mice were immunized with it (TR group, n = 15). Mice inoculated with the empty vector (EV group, n = 15) and normal saline (NS group, n = 15) were used as vector and blank control, respectively. Cytotoxic assay was carried out to measure the CTL activity. And indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was used to detect anti-TR-specific antibodies.

Results

TR group resulted in more efficient induction of CTL-specific cytolysis against TR polypeptide than both EV and NS groups (both P < 0.01). Vaccine-immunized mice had a higher equivalent concentration of anti-TR-specific antibodies (2,324 ± 238 μg/ml) than either of EV group (1,896 ± 533 μg/ml, P < 0.01) or NS group (1,736 ± 142 μg/ml, P < 0.01).

Conclusion

The novel recombinant TR DNA vaccine targeting at MUC1 of pancreatic cancer was constructed successfully, effectively expressing TR polypeptide in the transfected mammalian cells and inducing TR-specific CTL and antibody response.

Keywords: Pancreatic cancer, DNA vaccine, MUC1, Tandem repeat, Immune response

Introduction

The incidence of pancreatic cancer is increasing steadily, while the prognosis is relatively poor due to low resectability, malignant behavior and low sensitivity to anticancer agents. The overall 5-year survival rate is only 4% (Collins and Bloomston 2009; Freelove and Walling 2006; Zalatnai 2007). Treatment strategies targeting at the residual cancer cells, which are responsible for local recurrence and metastasis, are therefore necessary. Immunotherapy is expected to improve the prognosis of pancreatic cancer because it can act specifically against the tumor (Kawaoka et al. 2008). Adoptive immunotherapy for pancreatic cancer has included the use of peptide vaccine, dendritic cell (DC) vaccine and DNA vaccine. Among those approaches, DNA vaccine has an advantage over other vaccines because it can provide prolonged antigen expression, leading to amplification of immune responses, and inducing memory responses against weakly immunogenic tumor-associated antigens (TAA) (Chaudhuri et al. 2009). Moreover, DNA vaccination can activate both cellular and humoral immune responses as the encoded antigen is processed through both endogenous and exogenous pathways (Wolff et al. 1992; Chaudhuri et al. 2009). Therefore, DNA vaccine is a promising immunotherapy for pancreatic cancer (Wobser et al. 2006; Gaudernack 2006), the key of which is to pick out a suitable TAA overexpressed in pancreatic cancer cell.

Mucin 1 (MUC1) is a type I transmembrane protein containing a variable number of tandem repeats (TR) of a 20-amino acid sequence (GVTSAPDTRPAPGSTAPPAH) in its extracellular domain. In normal cells, TR is heavily glycosylated at the threonine and serine residues, with up to 70% carbohydrates by weight. In contrast, malignant cells including 90% of pancreatic cancer cells overexpress underglycosylated TR domains. Such characteristics of tumor-associated MUC1 make TR-derived epitopes potential targets for immune interventions (Mukherjee et al. 2001; Zhang et al. 2008; Pisarev et al. 2005). Hence, increased attention has been paid in the development of cancer vaccines with tumor-associated MUC1 (Ueda et al. 2005; Limacher and Acres 2007; Ryan et al. 2009).

Many MUC1-derived approaches showed that TR region was the key in forming MUC1-specific immunodominant B- and T-cell epitopes (Mitchell et al. 2007; Tang and Apostolopoulos 2008). Mice immunized with the MUC1-TR peptides (Zhang et al. 1996), MUC1-mannan fusion protein (Lees et al. 2000), or dendritic cells transfected with MUC1 peptides (Lepisto et al. 2008) could develop both humoral and cellular immune responses and partly suppress the growth of MUC1-expressing tumors. Although MUC1-specific antibodies and/or CTLs were detected in host and protected the host from attacking by tumor cells that express MUC1 (Johnen et al. 2001), they were not adequate to generate effective anti-tumor immunity to totally inhibit the growth of tumor (Brossart et al. 2000; Snyder et al. 2006). Moreover, clinical trials with MUC1 showed that MUC1 is a relatively poor immunogen in human beings (Kawaoka et al. 2008; Sugiura et al. 2008) and that the induction of clinically effective anti-tumor immune responses had not been achieved. Consequently, it is necessary to develop new vaccination protocols to induce strong anti-tumor immune responses that are applicable for the treatment of pancreatic cancer.

Reports of MUC1 DNA vaccines are insufficient, and most vaccines have been constructed with the full-length MUC1 cDNA (Johnen et al. 2001; Snyder et al. 2006; Sugiura et al. 2008). Some showed that MUC1-specific CTLs were undetectable after MUC1 DNA immunization but became evident only after tumor challenge. Many approaches have been studied to enhance MUC1-specific CTL responses, including double immunization and the immunization induced by MUC1 antigen coexpressing GM-CSF or Flt-3L (Fong et al. 2006). Double immunization could be induced by MUC1 vaccine combined with MUC1 protein (Mushenkova et al. 2005), DC (Kontani et al. 2002), or IL-18 encoding plasmid (Shi et al. 2007). However, no breakthrough has been made yet. The nature of MUC1-specific cellular immune responses (He et al. 2002) remains unclear. Furthermore, there are some unfavorable sequences, such as regressing sequences and flanking sequences in the full-length MUC1 sequence that could be possibly downregulate the DNA vaccine immunity (Sharav et al. 2007; Tang and Apostolopoulos 2008). Therefore, it is necessary to investigate how to construct a vaccine bearing no unfavorable sequence in order to upregulate its immunity.

Herein, we reported on the construction of a new recombinant TR DNA vaccine and the induced immune responses in mice. Only one TR sequence of MUC1 was used as the core sequence to reduce unfavorable sequences. A KOZAK sequence and a signal peptide sequence of MCP-1 were inserted before TR sequence to conquer self weak antigenicity to augment the MUC1-specific immune responses against the vaccine.

Materials and methods

Plasmid, cell lines and mice

The plasmid pcDNA3.1/Myc-his (+) A, used as eukaryotic expressing vector, GFP plasmid and mammalian COS7 cells were obtained from Key Laboratory of Medical Molecular Virology, Shanghai Medical College, Fudan University. EL4 (C57BL/6-derived mouse T lymphocyte lymphoma, H-2b) cells, used as targets for CTL cytotoxic assays, were purchased from Institute of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, SIBS, CAS. Female C57BL/6 (H-2b) mice (6–8 weeks old, 19–25 g weight, Shanghai SIPPR/BK Experimental Animal Co.) were housed in animal care facilities under isothermal conditions, with access to food and water ad libitum. The mice were kept for 5–7 days during an adaptation period before being subjected to experimental use. The experimental protocol was approved by the Shanghai Medical Experimental Animal Care Committee.

Plasmid construction

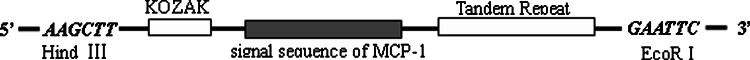

We designed a recombinant human TR (rhTR) gene encoding single TR polypeptide of MUC1. Following a KOZAK sequence, a signal peptide sequence of human monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) was inserted before the TR sequence (Fig. 1). The whole rhTR sequence is as following:  GCCGCCACC is a KOZAK sequence, followed in turn by the signal peptide sequence of MCP-1 (underlined) and the TR sequence (shadowed). On the end of the fragment is HindIII and EcoRI site, respectively. Then, the rhTR gene was cloned into the EcoRI and HindIII sites of plasmid pcDNA3.1/Myc-his (+) A to obtain the recombinant TR plasmid pcDNA3.1-TR/Myc-his (+) A (pTR plasmid). Confirmed by double restriction enzyme digestion with EcoRI and HindIII, the positive clone was identified to direct DNA sequencing.

GCCGCCACC is a KOZAK sequence, followed in turn by the signal peptide sequence of MCP-1 (underlined) and the TR sequence (shadowed). On the end of the fragment is HindIII and EcoRI site, respectively. Then, the rhTR gene was cloned into the EcoRI and HindIII sites of plasmid pcDNA3.1/Myc-his (+) A to obtain the recombinant TR plasmid pcDNA3.1-TR/Myc-his (+) A (pTR plasmid). Confirmed by double restriction enzyme digestion with EcoRI and HindIII, the positive clone was identified to direct DNA sequencing.

Fig. 1.

Schematics of the recombinant human TR (rhTR) gene. It encodes a single TR polypeptide of mucin 1 (MUC1), before which was inserted into a KOZAK sequence and a signal peptide sequence of human monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1)

Transfection assay and Western blot analysis

TR expression of the recombinant plasmid in mammalian cells was confirmed by transfection of pTR plasmid into COS7 cells using a standard calcium-chloride-mediated transfection protocol as described elsewhere (Felgner et al. 1987). Forty-eight hours after transfection, the culture supernatant and lysate supernatant of COS7 cells were collected to assay the intracellular and extracellular expression of TR by Western blot analysis. The synthesized TR polypeptide (GVTSAPDTRPAPGSTAPPAH, synthesized by Shenzhen Hybio Engineering Co. Ltd) was used as positive control. The membranes were blocked, and incubated overnight with anti-mouse MUC1 TR monoclonal antibody (VU 3C6, Hua Mei Company, Shanghai, China) at 1:500 dilution, recognizing the GVTSAPDTRPAP sequence. Goat antimouse IgG-horseradish peroxidase (Hua Mei Company, Shanghai, China) was used as secondary antibody at 1:1,000 dilution.

Mice and immunization

All DNA plasmids were extracted from transformed E. coli Top10F by alkaline SDS lysis and were maxi-extracted using a purification Maxi kit (Shanghai Watson Biotechnologies Inc.). The plasmids were then adjusted to an appropriate concentration in ddH2O and stored at −20°C.

Female C57BL/6 (H-2b) mice were immunized with 100 μg plasmid DNA of the recombinant pTR plasmid (TR group, n = 15) for a total volume of 100 μl by tibial muscle injection. Mice inoculated with the empty vector pcDNA3.1/Myc-his (+) A (EV group, n = 15) and normal saline (NS group, n = 15) were used as vector and blank controls, respectively. Four weeks later, all mice were inoculated again with the same solution.

Detection of antigen-specific immune response

Anti-MUC1 TR antibody detection

Two weeks after the second immunization, 0.5 ml blood from angular vein of the mouse was collected by scalp acupuncture. The supernatant (serum) was ready to detect the MUC1 TR-specific antibodies by using indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Synthesized TR polypeptide was used as coating antigen on 96 well polystyrene plates. For quantitative analysis, monoclonal antibody VU 3C6 was used as standard substance to assay the equivalent concentration of the specific anti-TR antibodies. That is, the potency of tested multiclonal antibodies was regarded equivalent to that of VU 3C6 at the same concentration.

CTL cytotoxic assay

Spleen cell suspensions were prepared and adjusted to the concentration of 5 × 106 cells per ml in 10% fetal calf serum RPMI 1640. The CTL activity was measured in triplicate using a standard 4-h calcein-release assay in U-bottom 96-well microplates (Lichtenfels et al. 1994).

EL4 was incubated with the synthesized TR polypeptide (1 mg/ml) for 2 h at 37°C and was confirmed containing TR by Western blot analysis. TR positive EL4 cells (EL4-TR) were then used as target cells in CTL cytotoxic assays. The expanded effector spleen cells were purified by Ficol and re-suspended in phenolene-free 10% fetal calf serum RPMI 1640, mixed with 5000 calcein AM-labeled targets at effector/target cells ratios (E/T) of 80/1, 40/1, 20/1 and 10/1. The plates were centrifuged at 100g for 3 min and further incubated at 37°C for 4 h. They were then centrifuged again and the supernatants were transferred into another 96-well microplate. The cytolysis of the targets was determined by measuring the fluorescence intensity (FI) of their supernatant using Fluoroskan Asent FL (Thermo Labsystem Co., Ltd, USA). The percentages of cytolysis were calculated as follows:

|

The final results of the specific cytolysis percentages were the value of EL4-TR minus the corresponding value of EL4.

Serum TNF-α and serum IFN-γ detection

In order to investigate Th1 cytokine response induced by DNA-based immunization, serum TNF-α and IFN-γ were detected by biotin–streptoavidin system ELISA using mouse TNF-α ELISA kit and mouse IFN-γ ELISA kit (Biosource Inc., USA), respectively. Briefly, a 96-well plate coated with anti-TNF-α antibody or anti-IFN-γ antibody incubated with diluted sera or various concentrations of standard antigen (mouse TNF-α: 1,250, 625, 312, 156, 78.1, 39.1, 19.5, 0 pg/ml; mouse IFN-γ: 125, 62.5, 31.2, 15.6, 7.8, 0 pg/ml).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were carried out by Statistical Package for the Social Sciences 12.0 (SPSS). Unpaired t-test was applied to evaluate the differences in antibody equivalent concentration, CTL activity of splenocytes and serum cytokine levels between different groups. P values (two-sided) of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Sequencing result and expression of pTR plasmid

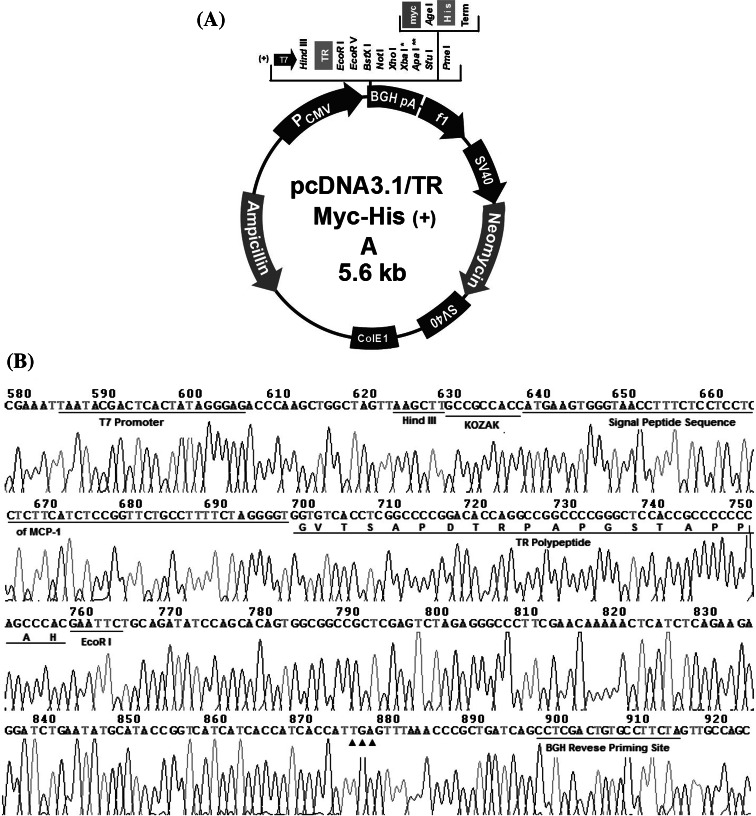

Confirmed by double restriction enzyme digestion, the positive clone was identified to direct DNA sequencing. The whole translation frame (from T7 promotor to BGH reverse priming site, including the rhTR gene) was exactly encoded in the recombinant plasmid (Fig. 2), which confirmed that it was correctly constructed. TR polypeptide was detected in cells transfected with the pTR plasmid (Fig. 3). In blank control, no TR polypeptide was detected either intra- or extracellularly (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Schematics of the recombinant pTR plasmid (a) and sequence of the inserted rhTR gene (b). Each plasmid contains the T7 promoter to drive expression of the rhTR gene, with a BGH reverse priming site, a TGA (filled triangle) termination codon, and contains a bacterial origin of replication (ori) and ampicillin resistance gene to enable plasmid propagation in bacteria. Amino acid residues beginning with the G are shown under the gene sequence, represent the polypeptide encoded by the TR gene

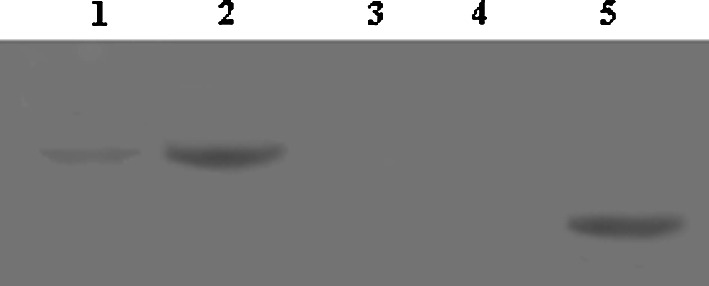

Fig. 3.

Western blot analysis for expression of TR polypeptide in COS7 cells. Forty-eight hours after transfection, the culture supernatant and lysate supernatant of COS7 cells transfected with the pTR plasmid (Lane 1 and Lane 2) or with the empty expression plasmid pcDNA3.1/Myc-his (+) A (Lane 3 and Lane 4) were collected for Western blot analysis to assay the intracellular (Lane 1 and Lane 3) and extracellular (Lane 2 and Lane 4) expression of TR polypeptide. The synthesized TR polypeptide (GVTSAPDTRPAPGSTAPPAH) (Lane 5) was used as positive control

Humoral immune responses

Equivalent anti-TR antibody concentration detected in this study was the equivalent potency of monoclonal antibody VU 3C6. The serum concentration of anti-TR antibody in vaccine-immunized mice (2,324 ± 238 μg/ml) was significantly higher (P < 0.01) than either of EV group (1,896 ± 533 μg/ml) or NS group (1,736 ± 142 μg/ml) 2 weeks after second immunization (Table 1).

Table 1.

Anti-TR-specific antibodies in immunized mice (μg/ml,  ± s)

± s)

| Group | n | Equivalent concentration |

|---|---|---|

| TR | 15 | 2,324 ± 238*# |

| EV | 15 | 1,896 ± 533▲ |

| NS | 15 | 1,736 ± 142 |

Two weeks after the second immunization, MUC1 TR-specific antibodies induced by pTR plasmid (TR group) or empty vector (EV group) or 0.9% NaCl solution (NS group) was detected by indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Monoclonal antibody VU 3C6 was used as standard substance for quantitative analysis. Equivalent concentration means that the potency of tested multiclonal antibodies was equivalent to that of VU 3C6 at the same concentration

* Compared with NS group, P = 0.000; # Compared with EV group P = 0.002; ▲ Compared with NS group, P = 0.231

Cellular immune responses

CTL cytotoxic assay delineated that the intramuscular delivery of the recombinant pTR plasmid into C57BL/6 mice resulted in more efficient induction of splenocytes cytolysis against EL4-TR than both groups [34.8 ± 3.1% vs. 9.2 ± 0.8% (EV group), vs. 6.1 ± 0.6% (NS group), both P < 0.01], with an effector/target cells ratio (E/T) of 80/1. When E/T fell to 10/1, the splenocytes specific cytolysis percentages of each group declined accordingly (TR group, 10.0 ± 2.6%; EV group, 2.6 ± 0.2% and NS group, 1.5 ± 0.1%). However, the differences among them were still prominent (Fig. 4a, P < 0.01). Furthermore, the CTL activities of splenocytes of immunized mice had a more significant specific killing activity toward EL4-TR target cells incubating with synthetic TR polypeptide than toward EL4 cells (P < 0.01 at E/T ratios of 80/1, 40/1, 20/1 and 10/1). VU 3C6, a monoclonal antibody of MUC1, recognizing GVTSAPDTRPAP sequence of TR polypeptide, was incubated with EL4-TR cells in advance to block out its target site. As a result, CTL killing activities against pretreated EL4-TR cells were obviously retrained (P < 0.01), which further identified that CTL killing activities was TR specific (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4.

Tandem repeat-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) response induced by twice immunization with different DNA vaccine candidates. Two weeks after the second immunization, the CTL activity of splenocytes from pTR plasmid-immunized mice (TR, n = 15) or empty vector control group (EV, n = 15) or blank control (NS, n = 15) was measured in triplicate by the standard 4-h calcein-release assay using target cells EL4-TR (incubated with the synthesized TR polypeptide) (a). EL4 cells were used as controls. VU 3C6, recognizing GVTSAPDTRPAP sequence of TR polypeptide, was incubated with EL4-TR cells (EL4-TR/VU 3C6) in advance to block out its target site to retrain the specific cytolysis (b). E/T = effector/target cells ratio

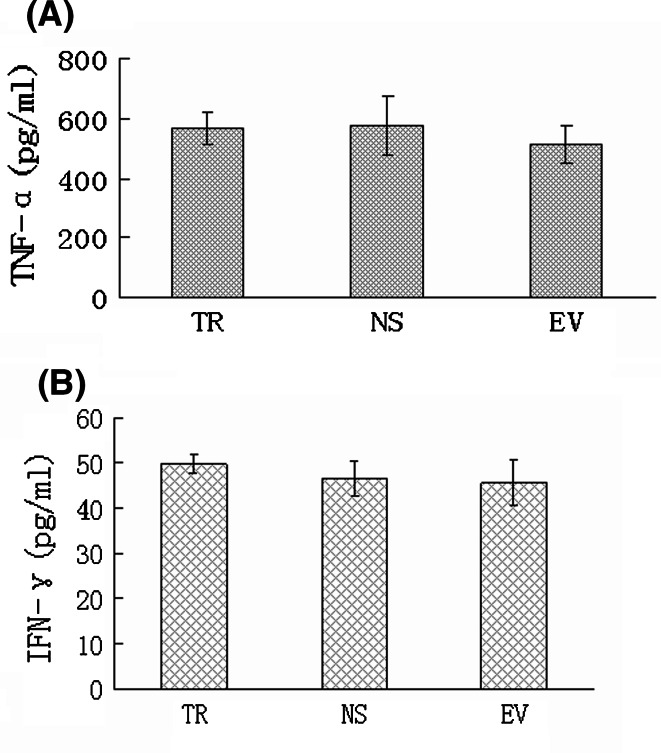

Cytokine responses

Serum cytokine was measured by ELISA to assess Th1 cytokine response induced by DNA-based immunization. Serum TNF-α level of vaccine-immunized mice (567 ± 52 pg/ml) was close to those of NS group (577 ± 99 pg/ml) and of EV group (514 ± 63 pg/ml) (Fig. 5a, P > 0.05) 2 weeks after the last immunization. However, no remarkable difference of serum IFN-γ concentration was found among the three groups (Fig. 5b, P > 0.05).

Fig. 5.

Serum TNF-α (a) and IFN-γ (b) level at time of 2 weeks after twice immunization. Serum cytokine concentration of pTR plasmid-immunized mice (TR, n = 15) or empty vector control group (EV, n = 15) or blank control group (NS, n = 15) was detected by biotin–streptoavidin system ELISA using mouse TNF-α ELISA kit and mouse IFN-γ ELISA kit

Discussion

Herein, we reported for the first time the successful construction of a novel recombinant TR DNA vaccine, merely using one TR polypeptide of MUC1 as the core sequence. Some DNA vaccines based on full-length MUC1 (Zhang et al. 2008; Acres and Limacher 2005) have been constructed and could generate immune responses specific for MUC1-expressing cancer cells in both mice and human beings (Yamamoto et al. 2005; Sangha and Butts 2007; Tang and Apostolopoulos 2008). However, some unfavorable sequences in whole MUC1 gene might cause the inhibition of the vaccine induced immunity (Sharav et al. 2007; Tang and Apostolopoulos 2008); therefore, DNA vaccines based on full-length MUC1 are insufficient to protect the host from attacking by tumor cells expressing MUC1 (Mukherjee et al. 2001; Snyder et al. 2006). Therefore, the new TR DNA vaccine, just encoding one TR polypeptide, is expected to eliminate immunosuppression of unfavorable sequences and to augment the MUC1-specific immune responses.

TR polypeptide, a 20 amino-polypeptides of MUC1 which is a tumor-associated antigen of pancreatic cancer, is however with weak antigenicity (Chu et al. 2006). To increase the antigenicity of TR polypeptide, a KOZAK sequence and a signal peptide sequence of MCP-1 was inserted continuously before TR sequence in our new pTR plasmid. KOZAK sequence could augment the accuracy and yield of TR interpretation (Garmory et al. 2003; Steinberg et al. 2005). While interpreting, signal peptide sequence of MCP-I (Chen et al. 1999) might guide TR to enter the endoplasmic reticulum. Thus, MHC-I antigen processing can be enhanced (Hayashi et al. 2007). The sequencing results (Fig. 2) confirmed that the constructed pTR plasmid absolutely met the design criteria, and the cell transfection assay in vitro and Western blot analysis (Fig. 3) showed that the recombinant DNA vaccine did express TR polypeptide in mammal COS7 cells, mainly intracellularly. Since the expressed rhTR was fused with epitopes of signal peptide of MCP-1, Myc and His, etc., its molecule was much larger than the synthesized TR polypeptide serving as positive control (Lane 5) (Fig. 3).

In this study, immunization with TR vaccine had induced remarkable TR-specific antibody responses in mice. The equivalent concentration of serum anti-TR antibodies in immunized mice was remarkably higher than those of EV group and of NS group (both P < 0.01). It implies that TR antigen expressed extracellularly in the host after immunization can be processed and presented through MHC-II as an exogenous antigen. Finally, CD4+ helper T lymphocytes were activated and TR-specific antibody was induced (Radosevich and Ono 2003). There is a large proportion of monoclonal antibody recognizing TR, for the varying epitopes on TR. As a result, the induced specific anti-TR antibodies are multiclonal.

Since the cellular immune reaction toward tumor cells is also of significance, we further investigate the induced CTL responses in immunized mice. CTL cytotoxic assay showed that the specific killing rate of splenocytes in vaccine-immunized mice toward EL4-TR cells, containing TR polypeptide through co-incubation, was significantly higher than those of EV group and NS group (P < 0.01, Fig. 4a) at varied E/T ratios. It illustrated that it was the rhTR gene cloned into the expression vector that mediated significant TR-specific CTL responses in vaccine-immunized mice. When the target cells were switched from EL4-TR cells to TR-negative EL4 cells, the splenocytes specific killing activity of the immunized mice declined obviously (P < 0.01, Fig. 4b), whereas when VU 3C6 acted with EL4-TR target cells in prior to block out its target site, the CTL killing activities was retrained (P < 0.01, Fig. 4b). These results further confirmed that the cellular immune responses induced by the new DNA vaccine were TR-specific CTL responses. It indicated that TR polypeptide can as well expressed intracellularly, and be processed and presented through MHC-I as an endogenous antigen. Consequently, antigen-specific CTL was activated (Harty and Bevan 1999).

Some studies had found Th1 immune responses, including Th1 cytokine secretion were induced after DNA-based immunization (Zhang et al. 2001; Jani et al. 2004). We are interested in investigating serum cytokine response after the last immunization. However, it seems to be so uneventful that no remarkable difference of serum TNF-α or IFN-γ concentration among the groups was observed. It might be due to faded responses of cytokine at the time of detection, or due to its secretion mode, such as self-secretion or para secretion, which cannot explode billows in the serum (Knutson and Disis 2005).

In summary, the novel recombinant TR DNA vaccine successfully constructed could induce TR-specific CTL responses and antibody responses toward target cells which are bearing TR polypeptide. The new vaccine should be able to induce MUC1-specific immune response to kill pancreatic cancer expressing MUC1, and it is hoped to become key immunotherapy in the future to improve the prognosis of pancreatic cancer.

Acknowledgments

This work was jointly supported by a grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 30801104) and a grant from Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (No. 08ZR1403000). I’d like to appreciate Mingyan Cai and Minjue Ju for their intelligent help.

Conflict of interest statement

We declare that we have no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

- TR

Tandem repeat

- MUC1

Mucin 1

- MCS

Multiple cloning sites

- MCP-1

Monocyte chemotactic protein-1

- CTL

Cytotoxic T lymphocytes

- DC

Dendritic cell

- IL

Interleukin

- E/T

Effector/target cells ratio

- ELISA

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

References

- Acres B, Limacher JM (2005) MUC1 as a target antigen for cancer immunotherapy. Expert Rev Vaccines 4:493–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brossart P, Wirths S, Stuhler G, Reichardt VL, Kanz L, Brugger W (2000) Induction of cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses in vivo after vaccinations with peptide-pulsed dendritic cells. Blood 96:3102–3108 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri D, Suriano R, Mittelman A, Tiwari RK (2009) Targeting the immune system in cancer. Curr Pharm Biotechnol 10:166–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen QR, Kumar D, Stass SA, Mixson AJ (1999) Liposomes complexed to plasmids encoding angiostatin and endostatin inhibit breast cancer in nude mice. Cancer Res 59:3308–3312 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu Y, Xia M, Lin Y, Li A, Wang Y, Liu R, Xiong S (2006) Th2-dominated antitumor immunity induced by DNA immunization with the genes coding for a basal core peptide PDTRP and GM-CSF. Cancer Gene Ther 13:510–519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins A, Bloomston M (2009) Diagnosis and management of pancreatic cancer. Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol 55:445–454 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felgner PL, Gadek TR, Holm M, Roman R, Chan HW, Wenz M, Northrop JP, Ringold GM, Danielsen M (1987) Lipofection: a highly efficient, lipid-mediated DNA-transfection procedure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 84:7413–7417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong CL, Mok CL, Hui KM (2006) Intramuscular immunization with plasmid coexpressing tumour antigen and Flt-3L results in potent tumour regression. Gene Ther 13:245–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freelove R, Walling AD (2006) Pancreatic cancer: diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician 73:485–492 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garmory HS, Brown KA, Titball RW (2003) DNA vaccines: improving expression of antigens. Genet Vaccines Ther 1:2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudernack G (2006) Prospects for vaccine therapy for pancreatic cancer. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 20:299–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harty JT, Bevan MJ (1999) Responses of CD8(+) T cells to intracellular bacteria. Curr Opin Immunol 11:89–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi A, Wakita H, Yoshikawa T, Nakanishi T, Tsutsumi Y, Mayumi T, Mukai Y, Yoshioka Y, Okada N, Nakagawa S (2007) A strategy for efficient cross-presentation of CTL-epitope peptides leading to enhanced induction of in vivo tumor immunity. J Control Release 117:11–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J, Shen D, O’Donnell MA, Chang HR (2002) Induction of MUC1-specific cellular immunity by a recombinant BCG expressing human MUC1 and secreting IL2. Int J Oncol 20:1305–1311 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jani D, Singh NK, Bhattacharya S, Meena LS, Singh Y, Upadhyay SN, Sharma AK, Tyagi AK (2004) Studies on the immunogenic potential of plant-expressed cholera toxin B subunit. Plant Cell Rep 22:471–477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnen H, Kulbe H, Pecher G (2001) Long-term tumor growth suppression in mice immunized with naked DNA of the human tumor antigen mucin (MUC1). Cancer Immunol Immunother 50:356–360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaoka T, Oka M, Takashima M, Ueno T, Yamamoto K, Yahara N, Yoshino S, Hazama S (2008) Adoptive immunotherapy for pancreatic cancer: cytotoxic T lymphocytes stimulated by the MUC1-expressing human pancreatic cancer cell line YPK-1. Oncol Rep 20:155–163 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson KL, Disis ML (2005) Tumor antigen-specific T helper cells in cancer immunity and immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother 54:721–728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontani K, Taguchi O, Ozaki Y, Hanaoka J, Tezuka N, Sawai S, Inoue S, Fujino S, Maeda T, Itoh Y, Ogasawara K, Sato H, Ohkubo I, Kudo T (2002) Novel vaccination protocol consisting of injecting MUC1 DNA and nonprimed dendritic cells at the same region greatly enhanced MUC1-specific antitumor immunity in a murine model. Cancer Gene Ther 9:330–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lees CJ, Apostolopoulos V, Acres B, Ong CS, Popovski V, McKenzie IF (2000) The effect of T1 and T2 cytokines on the cytotoxic T cell response to mannan-MUC1. Cancer Immunol Immunother 48:644–652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepisto AJ, Moser AJ, Zeh H, Lee K, Bartlett D, McKolanis JR, Geller BA, Schmotzer A, Potter DP, Whiteside T, Finn OJ, Ramanathan RK (2008) A phase I/II study of a MUC1 peptide pulsed autologous dendritic cell vaccine as adjuvant therapy in patients with resected pancreatic and biliary tumors. Cancer Ther 6(B):955–964 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenfels R, Biddison WE, Schulz H, Vogt AB, Martin R (1994) CARE-LASS (calcein-release-assay), an improved fluorescence based test system to measure cytotoxic T lymphocyte activity. J Immunol Methods 172:227–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limacher JM, Acres B (2007) MUC1, a therapeutic target in oncology. Bull Cancer 94:253–257 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell MS, Lund TA, Sewell AK, Marincola FM, Paul E, Schroder K, Wilson DB, Kan-Mitchell J (2007) The cytotoxic T cell response to peptide analogs of the HLA-A*0201-restricted MUC1 signal sequence epitope, M1.2. Cancer Immunol Immunother 56:287–301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee P, Ginardi AR, Madsen CS, Tinder TL, Jacobs F, Parker J, Agrawal B, Longenecker BM, Gendler SJ (2001) MUC1-specific CTLs are non-functional within a pancreatic tumor microenvironment. Glycoconj J 18:931–942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mushenkova N, Moiseeva E, Chaadaeva A, Den Otter W, Svirshchevskaya E (2005) Antitumor effect of double immunization of mice with mucin 1 and its coding DNA. Anticancer Res 25:3893–3898 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisarev VM, Kinarsky L, Caffrey T, Hanisch FG, Sanderson S, Hollingsworth MA et al (2005) T cells recognize PD(N/T)R motif common in a variable number of tandem repeat and degenerate repeat sequences of MUC1. Int Immunopharmacol 5:315–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radosevich M, Ono SJ (2003) Novel mechanisms of class II major histocompatibility complex gene regulation. Immunol Res 27:85–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan SO, Vlad AM, Islam K, Gariépy J, Finn OJ (2009) Tumor-associated MUC1 glycopeptide epitopes are not subject to self-tolerance and improve responses to MUC1 peptide epitopes in MUC1 transgenic mice. Biol Chem 3907:611–618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sangha R, Butts C (2007) L-BLP25: a peptide vaccine strategy in non small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res 13:s4652–s4654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharav T, Wiesmüller KH, Walden P (2007) Mimotope vaccines for cancer immunotherapy. Vaccine 25:3032–3037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi FF, Gunn GR, Snyder LA, Goletz TJ (2007) Intradermal vaccination of MUC1 transgenic mice with MUC1/IL-18 plasmid DNA suppresses experimental pulmonary metastases. Vaccine 25:3338–3346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder LA, Goletz TJ, Gunn GR, Shi FF, Harris MC, Cochlin K, McCauley C, McCarthy SG, Branigan PJ, Knight DM (2006) A MUC1/IL-18 DNA vaccine induces anti-tumor immunity and increased survival in MUC1 transgenic mice. Vaccine 24:3340–3352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg T, Ohlschläger P, Sehr P, Osen W, Gissmann L (2005) Modification of HPV 16 E7 genes: correlation between the level of protein expression and CTL response after immunization of C57BL/6 mice. Vaccine 23:1149–1157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiura D, Aida S, Denda-Nagai K, Takeda K, Kamata-Sakurai M, Yagita H, Irimura T (2008) Differential effector mechanisms induced by vaccination with MUC1 DNA in the rejection of colon carcinoma growth at orthotopic sites and metastases. Cancer Sci 99:2477–2484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang CK, Apostolopoulos V (2008) Strategies used for MUC1 immunotherapy: preclinical studies. Expert Rev Vaccines 7:951–962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda M, Miura Y, Kunihiro O, Ishikawa T, Ichikawa Y, Endo I, Sekido H, Togo S, Shimada H (2005) MUC1 overexpression is the most reliable marker of invasive carcinoma in intraductal papillary-mucinous tumor (IPMT). Hepatogastroenterology 52:398–403 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wobser M, Keikavoussi P, Kunzmann V, Weininger M, Andersen MH, Becker JC (2006) Complete remission of liver metastasis of pancreatic cancer under vaccination with a HLA-A2 restricted peptide derived from the universal tumor antigen survivin. Cancer Immunol Immunother 55:1294–1298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff JA, Ludtke JJ, Acsadi G, Williams P, Jani A (1992) Long-term persistence of plasmid DNA and foreign gene expression in mouse muscle. Hum Mol Genet 1:363–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto K, Ueno T, Kawaoka T, Hazama S, Fukui M, Suehiro Y, Hamanaka Y, Ikematsu Y, Imai K, Oka M, Hinoda Y (2005) MUC1 peptide vaccination in patients with advanced pancreas or biliary tract cancer. Anticancer Res 25:3575–3579 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalatnai A (2007) Novel therapeutic approaches in the treatment of advanced pancreatic carcinoma. Cancer Treat Rev 33:289–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Graeber LA, Helling F, Ragupathi G, Adluri S, Lloyd KO, Livingston PO (1996) Augmenting the immunogenicity of synthetic MUC1 peptide vaccines in mice. Cancer Res 56:3315–3319 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Taylor MG, Johansen MV, Bickle QD (2001) Vaccination of mice with a cocktail DNA vaccine induces a Th1-type immune response and partial protection against Schistosoma japonicum infection. Vaccine 20:724–730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Zhang H, Shi H, Yu X, Kong W, Li W (2008) Induction of immune response and anti-tumor activities in mice with a DNA vaccine encoding human mucin 1 variable-number tandem repeats. Hum Immunol 69:250–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]