Abstract

Introduction/Aims

Training is essential for future health care providers to effectively communicate with limited English proficient (LEP) patients during interpreted encounters. Our aim is to describe an innovative skill-based medical school linguistic competency curriculum and its impact on knowledge and skills.

Setting

At Stanford University School of Medicine, we incorporated a linguistic competency curriculum into a 2-year Practice of Medicine preclinical doctoring course and pediatrics clerkship over three cohorts.

Program Description

First year students participated in extensive interpreter-related training including: a knowledge-based online module, interactive role-play exercises, and didactic skill-building sessions. Students in the pediatrics clerkship participated in interpreted training exercises with facilitated feedback.

Program Evaluation

Knowledge and skills were evaluated in the first and fourth years. First year students’ knowledge scores increased (pre-test = 0.62, post-test = 0.89, P < 0.001), and they demonstrated good skill attainment during an end-year performance assessment. One cohort of students participated in the entire curriculum and maintained performance into the fourth year.

Discussion

Our curriculum increased knowledge and led to skill attainment, each of which showed good durability for a cohort of students evaluated 3 years later. With a growing LEP population, these skills are essential to foster in future health care providers to effectively communicate with LEP patients and reduce health disparities.

KEY WORDS: interpreter use, evaluation of skills undergraduate medical education, cultural competency, curriculum, cultural competency/education, educational measurement/methods

INTRODUCTION AND AIMS

With a growing linguistically diverse population1, health care providers need to successfully navigate medical encounters with limited English proficient (LEP) patients. Although federal statutes protect against discrimination based on patients' national origin and language2, LEP patients receive inferior quality of and access to care3. Patient-physician interactions, already riddled with communication barriers, are particularly challenging during LEP visits. Health disparities due to communication differences leave LEP patients with poorer understanding of diagnoses and medications4, reduced interpersonal care measures5, and lower satisfaction measures of the encounter6.

Trained interpreters during LEP encounters improve quality of patient-physician communication7, patient satisfaction 8 and clinical outcomes9. Educating health care providers to work effectively with trained interpreters is becoming a priority in medical education.

Recent education standards have prompted the implementation of interpreter-related training for undergraduate medical education (UGME). The accrediting body for UGME programs, the Liaison Committee on Medical Education, has issued cultural competency standards for graduating medical students to meet the needs of diverse patients, including addressing biases that affect quality of care in the LEP population10. The Association for American Medical Colleges tool for assessing cultural competency training (TACCT) emphasizes specific knowledge and skills of working effectively with interpreters in medical student training11.

Knowledge-based training has shown to improve practicing physicians' communication strategies during interpreted encounters12; however, training needs to move beyond knowledge acquisition to incorporate skills13. Recognizing that a skill-based approach may improve care for LEP patients, we designed a systematic longitudinal curriculum to foster developmental skill progression for effective communication during LEP encounters.

In this paper we describe an experiential curriculum preparing medical students to address the needs of LEP patients through instruction on federal and local mandates, LEP health disparities, and communication strategies during LEP encounters. Our primary evaluation interests were to determine: the level of skill performance achieved after the first year curriculum, curricular impact on knowledge regarding LEP encounters, and performance maintenance into the fourth year for one cohort. For evaluation of skills attainment, we used a simulated LEP encounter as part of an objective structured clinical examination (OSCE); for knowledge, we administered a previously validated pre- and post-test in the first year. We also evaluated maintenance of knowledge and skill for our first cohort using the same knowledge test and another simulated LEP encounter administered as part of a high-stakes OSCE using the same valid and reliable checklists to determine the curricular impact on knowledge and skills.

PROGRAM AND SETTING

In 2005, we instituted cultural competency curriculum at Stanford University School of Medicine (Stanford) to increase medical students’ overall knowledge and skills on cultural, linguistic, and other contributing factors to health disparities. The linguistic competency curriculum’s purpose was to increase awareness of language's function during the clinical interview14, emphasize the impact of language barriers, and build effective communication skills during interpreted encounters. We developed strategies to evaluate the 4-year curriculum for specific domains of linguistic competency learning. Specific learning objectives and activities for each session are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Longitudinal Medical School Curriculum to Work Effectively with Interpreters

| Year | Session title | Session description | Curriculum or evaluation* | Learning objectives |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pre-session homework assignment: online module† | Interactive online web-based module consisting of 6 video vignettes showcasing working with both untrained and trained interpreters | Curriculum (K, S), evaluation (K) | 1. Recognize techniques during LEP encounters and the impact of poor interpretation |

| 2. Identify legal, ethical, and cultural issues arising in the cross-language medical interview | ||||

| 3. Discuss unique aspects of caring for immigrants. | ||||

| 1 | Clinical skills: working with interpreters (interpreter session #1) | 75-min session with a short didactic section on working with interpreters followed by a brief demonstration. Students then formed 4-person groups to practice skills during scripted role-play exercises | Curriculum (K, S) | 1. Identify when to work with an interpreter |

| 2. Demonstrate effectively working with interpreters | ||||

| 3. Gain awareness of linguistic challenges and developing relationships with patients | ||||

| 4. Define relationships and roles with interpreter and patient | ||||

| 5. Reinforce effective communication strategies. | ||||

| 1 | Problem-focused patient evaluation (interpreter session #2) | 230-min session with 4 focused standardized patient (SP) exercises, including one with LEP patient and standardized interpreter (SI) | Curriculum (S) | 1. Refine the approach to a problem-focused interview and examination |

| 2. Integrate clinical reasoning skills into patient encounters | ||||

| 3. Synthesize advanced interviewing techniques with physical examination. | ||||

| 1 | Year 1 exam | High-stakes end-year exam OSCE exams, one including an LEP patient presenting with a cough and working with an untrained SI | Evaluation (S) | 1. Elicit the patient’s perspective on the current illness |

| 2. Perform a thorough focused examination | ||||

| 3. Perform a focused history and physical examination while appropriately managing an untrained interpreter. | ||||

| 3 | Pediatrics simulated exercise | Students take turns in a round-robin 4-station exercise, one consisting of working with a LEP SP and SI | Curriculum (K, S) | 1. Emphasize value of eliciting the patient’s expectations for treatment |

| 2. Reinforce principles of working effectively with trained medical interpreters. | ||||

| 4 | Year 4 CPX exam‡ | 9-station high-stakes overall assessment including one station with LEP patient requiring suture removal | Evaluation (K, S) | 1. Manage the encounter with the LEP SP and untrained interpreter (SI) |

| 2. Remove three sutures and answer patient questions. |

*Describes the content as curriculum or evaluation piece, or both, with knowledge (K)- or skill (S)-based learning objectives

†Modified from NYU School of Medicine. Working with interpreters module (http://edinfo.med.nyu.edu/interpreter/). Accessed April 24, 2009

‡Fourth year CPX exam administered in 2008 only to 2005 cohort

Year 1 As part of our doctoring course, Practice of Medicine (POM), students received health disparities and communication skills training, including communicating effectively during interpreted encounters. Prior to their first in-class session on interpreted encounters, students completed an interactive Web module consisting of patient-physician-interpreter video vignettes highlighting strategies and common mistakes while working with interpreters15,16.

The in-class session began with a brief didactic emphasizing language access issues and communication strategies. Scripted role-play followed, with trained standardized patients (SP) acting as LEP patients and standardized interpreters (SI) as different types of medical interpreters (ad hoc untrained, family, and trained). We teach the use of trained interpreters as “standard of care," although these teaching exercises also portrayed other types of interpreted encounters to demonstrate their potential pitfalls. Students had the opportunity for skill practice in interviewing SPs and SIs, followed by debriefs with facilitators.

During the third quarter of the first year, students participated in a second skill-based session where they encountered a problem-focused simulated LEP patient. In this session, students interview an SP working with an SI, followed by debriefing with student peers and a faculty facilitator.

Year 3 Students participated in another skill-based simulated patient encounter during their required pediatric clerkship. Over four different scenarios, each student in a group of four took a turn practicing their skills while being observed remotely by their three peers. At the end of the interview, the observing students and facilitator provide structured feedback. The practice is repeated with different scenarios until each of the four students conducted one such interview. Finally, facilitators discuss language-related disparities and legal mandates for LEP patients.

PARTICIPANTS

All first year students (52% women) received this curriculum, beginning with the 2005-2006 matriculating class. All students completed all evaluation and curricular components, though they could opt out of having their data included in some research analyses. We examined knowledge and skill performance for cohorts of students in 2005, 2006, and 2007; only the 2005 cohort is included in the analysis of maintenance of knowledge and skill into the fourth year.

PROGRAM EVALUATION

We evaluated the interpreter curriculum using measures of knowledge and communication behaviors in the first year of training for all three cohorts, and performed a longitudinal analysis of maintenance of knowledge and skill for the 2005 cohort in their fourth year.

Knowledge In conjunction with the online LEP module, first year students completed a validated nine-item pre- and post-module knowledge test on health disparities, language access, and rights of LEP patients16. The same nine knowledge items were used during the OSCE in the fourth year, for the 2005 cohort.

Skill We evaluated students’ LEP skill-based performance during one station of our high-stakes OSCE at the end of the first year for all three cohorts, and again in the fourth year for the 2005 cohort. During these exams, SPs, SIs, and observers assess students’ clinical competence in history taking, physical examination, information sharing, and general patient-physician interaction domains, using previously validated checklists17. In addition, students were rated on skills specific to interpreted encounters with valid and reliable measures of the Interpreter Impact Rating Scale (IIRS), Faculty Observer Rating Scale (FORS), and Interpreter Scale (IS18,19, utilizing the perspectives of the SP, SI, and observer, respectively. A 5-point Likert scale evaluated students’ performance (ranging from 1 = “poor” to 5 = “excellent”).

Our Standardized Patient Program recruits and trains bilingual SPs and medical interpreters to evaluate students using these checklist items. The exhaustive training process ensures inter-rater reliability across all checklists with focused training on reliably evaluating students20.

For the first year OSCE, we evaluated skills using one case during a two-station exam, in which a LEP SP presents with a cough. The SP is monolingual in Russian, Spanish, Vietnamese, or Mandarin, while the SI portrays an untrained ad hoc interpreter. Students must effectively manage the encounter with these challenges in addition to performing a focused medical interview and physical exam. Students received verbal and written formative feedback on their performance from all evaluators.

We integrated a similar encounter into the nine-station, high-stakes OSCE administered in the fourth year to determine whether knowledge and skill performance achieved at the end of the first year was maintained over time. In this fourth year OSCE, the SP requires a minor procedure, but does not speak English. Students must perform typical clinical assessments as well as manage the interpersonal dimension presented by the patient’s lack of English proficiency. Students were evaluated using the same interpreter checklists (IIRS, IS, and FORS). We subsequently compared these results to their performance in the first year OSCE and contrasted performance for students within this cohort to their colleagues who did not complete the first year exercises.

Data analysis We describe the overall first year performance for all three cohorts, as well we pre/post comparisons on the knowledge-based assessment (Wilcoxon signed-rank test). We examined the durability of change in knowledge and skills performance between the first and fourth year for the 2005 cohort and whether completion of the pediatric clerkship helped sustain performance (chi-squared). We also compared the performance of this cohort to other students completing the fourth year OSCE who had not participated in this curriculum (Wilcoxon ranked-sum test). We performed all statistical analysis using Stata/SE 10.1 for Macintosh (StataCorp Statistical Software: Release 10.1, Stata Corporation, College Station, TX). The Institutional Review Board at Stanford University approved the study.

RESULTS

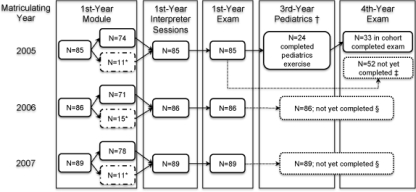

Of our three cohorts of first year students, 260 (100%) participated in the first year interpreter curriculum and exam, and 85% (n = 223) agreed to allow their evaluation data to be used for the knowledge assessment. Of 85 students in the 2005 cohort, 33 (39%) completed the curriculum and all assessments (first and fourth year OSCEs) (see Fig. 1); the remaining students have not yet completed the OSCE in large part because many of our students pursue 1 or more years of research or additional degrees following the second year, thereby delaying completion of the pediatric clerkship LEP curriculum and fourth year knowledge and skill re-assessment. Figure 1 summarizes the student cohorts included in these analyses.

Figure 1.

Interpreter curriculum and evaluation timeline with student distribution by cohort over a 3-year period. *Students withdrew from the research portion of the knowledge pre-and post-test, but subsequently participated in the curriculum. These students consented to participate in the remaining educational and research activities. All students in each cohort participated in the module as a mandatory assignment. †Although the pediatrics clerkship rotation is required curriculum, it is not necessary to complete by the end of the third year, accounting for the 24 students in the 2005 cohort who completed the exercise prior to the fourth year exam. ‡Of 85 students in the 2005 cohort, 52 students chose to pursue other academic endeavors between their preclinical and clerkship years. These students did not take the 4th year exam; however, they will take the exam in subsequent years. §Students in the later cohorts have not yet participated in the 4th year exam.

Knowledge Post-test scores (0.89 SD 0.13) were significantly higher than pre-test scores (0.62, SD 0.25, P < 0.001), representing a 27% improvement on the nine-point scale.

By the fourth year, the 2005 cohort students maintained their knowledge with no significant decrement in post-test knowledge scores.

Skill All first year students completed the end-year OSCE. The internal consistency measure for each checklist is acceptable; Cronbach's α ranged from 0.700 to 0.888. Students performed reasonably well on this end-year performance assessment, with mean scores of 0.69, 0.66, and 0.56 on the IRS, IS, and FORS scales, respectively. These scores indicate “good” to “very good” performance (0 = poor; 1 = excellent). The 2005 cohort showed no decrement in performance on the fourth year OSCE by any of these measures; those in the 2005 cohort who participated in all linguistic curriculum including pediatrics (n = 24) had a slightly higher level of performance than their colleagues in the cohort, but this result was not statistically significant. However, 2005 cohort students performed significantly better than their fourth year students not exposed to the curriculum. The skill results are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Global Ratings of First and Fourth Year Students’ Performance during Skill-based High-stakes Standardized Patient Exams with Limited English Proficient Patients and Interpreters

| Students | N | IIRS* mean (SD) | IS† mean (SD) | FORS‡ mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st year | 260 | 0.69 (0.16) | 0.66 (0.16) | 0.56 (0.16) |

| 4th year | 78 | 0.66 (0.19) | 0.75 (0.15)§ | 0.58 (0.20) |

| Non-2005 cohort (4th year) | 45 | 0.61 (0.16) | 0.76 (0.11) | 0.54 (0.18) |

| 2005 cohort (4th year) | 33 | 0.72 (0.21)‖ | 0.74 (0.19) | 0.64 (0.22)‖ |

*Interpreter Impact Rating Scale (IIRS), standardized patient rates student on overall satisfaction with the encounter

†Interpreter Scale (IS), standardized interpreter rates student on overall satisfaction with the encounter

‡Faculty Observer Rating Scale (FORS), trained observer rates student on global rating of student’s effectiveness in using the interpreter

§Statistically significant (P < 0.001) difference in IS mean scores between first and fourth year performance

‖Statistically significant (P < 0.05) difference between 2005 cohort compared with fourth year students who did not complete the first year exercises

DISCUSSION

We have reported a descriptive study of an integrated longitudinal knowledge- and skill-based curriculum for medical students and evaluation of specific skills associated with good communication and behavior during interpreted LEP encounters. The evaluation results showed significant improvement in preclinical students’ knowledge as well as good skill attainment associated with this curriculum in the first year. Evaluation of knowledge and skills for one cohort in their fourth year showed no decrement from the first year assessment, suggesting durability of the curricular impact over time. Exposure to additional curriculum in our pediatrics exercise may have helped reinforce knowledge and skills.

Our educational innovation has several limitations. First, our curriculum required significant resources to implement, including recruiting bilingual actors for role plays and exams, and paying for additional raters during the OSCEs. The fourth year LEP OSCE station was only administered 1 year, limiting our ability to assess all participants for durability of learning.

Second, the structured curriculum focused on first year students, with variable exposure to interpreted LEP encounters in subsequent years. Additionally, there may have been systematic differences in 2005 cohort students from students not exposed to our curriculum, as well as those who completed the pediatrics clerkship prior to the fourth year evaluation.

Also, while every effort was made to emphasize the value of working with trained medical interpreters during trainings and exams, using ad hoc standardized interpreters during the OSCEs may have unintentionally communicated tolerance for using untrained interpreters during LEP encounters.

Lastly, residents and faculty have variable training in working with LEP patients and may be sending mixed messages role modeling, scheduling, and working with interpreters during LEP encounters.

Additional questions arise from this study, such as how each curricular element affects fourth year performance and what timing of curriculum results in maximum durability. To answer these questions, we will continue to integrate LEP health disparities topics into the UGME curriculum.

Recognizing the importance of working effectively with interpreters has given rise to the need for a skill-based UGME interpreter curriculum; we were able to implement a feasible and successful longitudinal skill-based curriculum and evaluate its impact on knowledge and skills. With more students trained in linguistic competency, we can be more optimistic about meeting the demands of a growing LEP population.

Acknowledgments

All authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Dr. Pree Basaviah, Ms. Madika Bryant, and Ms. Julianne Arnall in the implementation process of this curriculum. The authors also acknowledge funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, award no. K07 HL079330 “Integrated Immersive Approaches to Cultural Competence” (2005-2010) and the Association of American Medical Colleges grant initiative "Enhancing Cultural Competence in Medical Schools" (2005-2008) supported by the California Endowment.

Conflict of Interest The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.U.S. Census Bureau. Language Use and English-Speaking Ability: 2000. Census 2000 Brief. Available at: (http://www.census.gov/prod/2003pubs/c2kbr-29.pdf) Accessed January 21, 2010.

- 2.Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. 42 U.S.C. 2000d ed; 1964.

- 3.Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington: National Academies Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilson E, Chen AH, Grumbach K, Wang F, Fernandez A. Effects of limited English proficiency and physician language on health care comprehension. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(9):800–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0174.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ngo-Metzger Q, Sorkin DH, Phillips RS, et al. Providing high-quality care for limited English proficient patients: the importance of language concordance and interpreter use. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(Suppl 2):324–30. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0340-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morales LS, Cunningham WE, Brown JA, Liu H, Hays RD. Are Latinos less satisfied with communication by health care providers? J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14(7):409–17. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.06198.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hornberger J, Itakura H, Wilson SR. Bridging language and cultural barriers between physicians and patients. Public Health Rep. 1997;112(5):410–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baker DW, Hayes R, Fortier JP. Interpreter use and satisfaction with interpersonal aspects of care for Spanish-speaking patients. Med Care. 1998;36(10):1461–70. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199810000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karliner LS, Perez-Stable EJ, Gildengorin G. language divide. The importance of training in the use of interpreters for outpatient practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(2):175–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30268.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liason Committee on Medical Education. LCME Accreditation Standards. Available at: (http://www.lcme.org/functionslist.htm) Accessed January 21, 2010.

- 11.Lie D, Boker J, Crandall SJ, et al. Revising the Tool for Assessing Cultural Competence Training (TACCT) for curriculum evaluation: Findings derived from seven US schools and expert consensus. Med Educ Online. 2008;13(11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Bischoff A, Perneger TV, Bovier PA, Loutan L, Stalder H. Improving communication between physicians and patients who speak a foreign language. Br J Gen Pract. 2003;53(492):541–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gurman TA, Moran A. Predictors of appropriate use of interpreters: identifying professional development training needs for labor and delivery clinical staff serving Spanish-speaking patients. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2008;19(4):1303–20. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dysart-Gale D. Clinicians and medical interpreters: negotiating culturally appropriate care for patients with limited English ability. Fam Community Health. 2007;30(3):237–46. doi: 10.1097/01.FCH.0000277766.62408.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kalet AL, Mukherjee D, Felix K, et al. Can a web-based curriculum improve students' knowledge of, and attitudes about, the interpreted medical interview? J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(10):929–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0193.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lie D, Bereknyei S, Kalet A, Braddock C., 3rd Learning outcomes of a web module for teaching interpreter interaction skills to pre-clerkship students. Fam Med. 2009;41(4):234–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Makoul G. Essential elements of communication in medical encounters: the Kalamazoo consensus statement. Acad Med. 2001;76(4):390–3. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200104000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lie D, Bereknyei S, Braddock C, 3rd, Encinas J, Ahearn S, Boker J. Assessing medical students' skills in working with interpreters during patient encounters: a validation study of the interpreter scale. Acad Med. 2009;84(5):8. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31819faec8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lie D, Boker J, Bereknyei S, Ahearn S, Fesko C, Lenahan P. Validating measures of third year medical students' use of interpreters by standardized patients and faculty observers. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(Suppl 2):336–40. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0349-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grant J, Arnall J, Bereknyei S, et al. Preparing medical students to work with interpreters: successful team training techniques to enhance the effectiveness of standardized patients. Presented at: Western Group on Educational Affairs (WGEA) Regional Conference. Pacific Grove, CA. April 28, 2008.