Abstract

PURPOSE

To assess the significance of CA-125 regression as a prognostic indicator and predictor of optimal cytoreduction at interval debulking surgery (IDS) in women with ovarian or primary peritoneal carcinoma receiving neo-adjuvant chemotherapy.

METHODS

63 women treated between 2004 and 2007 with neoadjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy followed by IDS were studied retrospectively. Preoperative CA-125 values were used to calculate a regression coefficient (CA-125r) using exponential regression analysis. Outcome endpoints were overall survival (OS), time to CA-125 progression by Rustin criteria (TTC) and time to second-line treatment (TTS).

RESULTS

Women with a CA-125 half-life greater than 18 days had a significantly worse OS compared to those with a half-life less than 12 days on univariate testing [HR 3.34, 95% CI: 1.25-8.94, p=0.017]. On multivariable analysis, CA-125r was an independent predictor of OS [HR 1.18 (per 0.01 increase in CA-125r), 95% CI: 1.01-1.40, p=0.043]. CA-125r was independently predictive of TTC and TTS [HR 1.17, p≈0.03 for each]. CA-125r was also predictive of achieving optimal cytoreduction at IDS (AUC 0.756, p<0.001).

CONCLUSIONS

CA-125 regression rate during pre-operative neo-adjuvant chemotherapy is of independent prognostic value. CA-125 regression rate strongly predicts for optimal cytoreduction.

Keywords: CA-125 regression, ovarian cancer, neoadjuvant chemotherapy, interval debulking surgery

Introduction

The conventional treatment of advanced ovarian and primary peritoneal carcinoma is initial cytoreductive surgery followed by chemotherapy. In recent years, an alternative treatment approach of platinum-based chemotherapy followed by interval debulking surgery (IDS) has increasingly been adopted, particularly in high-risk surgical candidates and / or patients where optimal primary cytoreduction is felt unlikely to be possible. Whether such an approach is suitable for all women with stage III and IV disease remains controversial [1,2]. The recently presented results of the EORTC-GCG phase III randomized study, suggests that neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) achieves higher rates of optimal cytoreduction, with reduced morbidity, for equivalent survival in comparison to up-front surgery [3]. The results of two further randomized phase III trials (MRC CHORUS and JCOG0206) are awaited.

A potential advantage of the NAC approach is that it can provide the treating clinician with early information regarding the chemosensitivity of the tumor using clinical, radiological and tumor marker criteria. Decreasing CA-125 levels are known to correlate with response to chemotherapy [4]. In the post-operative setting, absolute CA-125 levels and CA-125 regression are known to be prognostic of outcome [5,6]. In the neoadjuvant setting, where the effect of surgery is excluded, the value of CA-125 remains unclear. The ability to predict optimal cytoreduction, a factor strongly associated with improved outcome [7], is desirable. Recent studies examining absolute CA-125 levels pre-operatively have reported conflicting results [8,9]. The value of CA-125 regression during NAC as a predictor of optimal cytoreduction at IDS has not been explored.

In the current study, we have examined whether CA-125 regression during NAC predicts for optimal cytoreduction and correlates with outcome in women with newly diagnosed ovarian or primary peritoneal cancer.

Patients and Methods

Patients

We conducted a retrospective study of women diagnosed with advanced ovarian or primary peritoneal carcinoma, treated in our institution with neoadjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy followed by IDS between 2004 and 2007. Standard IDS consisted of total abdominal hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, omentectomy and para-aortic and pelvic lymph node dissection. We included women with FIGO stage III, or IV disease as defined by baseline CT imaging, biopsy and/or cytology. Women who had initial laparotomy with minimal, or no debulking (e.g. for bowel obstruction, acute abdomen, omentectomy only, or “open and close” laparotomy) were included provided they subsequently had chemotherapy followed by IDS. Patients with germ-cell, purely stromal or borderline histology, tumors of unknown primary and women with synchronous malignancies were excluded.

Statistical analysis

SPSS (version 15; Chicago, IL, USA) and R (R Development Core Team, Vienna, Austria) software packages were used for statistical analysis. Estimate of the survival function were computed using the Kaplan-Meier method. Cox's proportional hazards regression [10] was used to evaluate univariate and independent multivariable associations with the effect of clinical, pathological and CA-125 kinetic parameters on outcome endpoints. Age, site of primary, morphology, grade, FIGO stage, presence of ascites, degree of cytoreduction as defined by the surgeon (≤ or >1 cm residual disease), chemotherapy regimen, baseline albumin, albumin prior to IDS (as log2 continuous variables), and preoperative CA-125 regression coefficient (CA-125r) (continuous variable and as tertiles) were considered for all patients. The multivariable model included age, stage, grade, pre-IDS albumin, degree of cytoreduction, and CA-125r (continuous variable only). Receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was performed to evaluate CA-125r as a predictor of optimal cytoreduction. Independent predictive ability of optimal cytoreduction using CA-125r was evaluated using multiple logistic regression.

Outcome endpoints were defined as follows: Overall survival (OS) - interval between date of first chemotherapy cycle and death, or last follow up; time to CA-125 progression (TTC) - interval between date of first chemotherapy cycle and date of CA-125 progression from nadir value, as per Gynecologic Cancer Intergroup (GCIG) criteria [11], or date of death, or last follow up; time to second-line treatment (TTS) - interval between date of first chemotherapy cycle and date of commencing 2nd line, or rechallenge, treatment (chemotherapy, tamoxifen, radiotherapy, surgery), or date of decision for best supportive care only, or date of death, or last follow up.

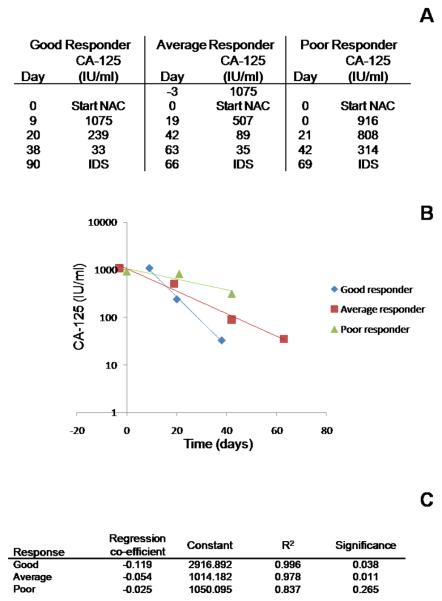

CA-125 regression coefficients

Serum CA-125 levels measured from time of diagnosis until death, or last follow up were recorded. The assay was performed by the Clinical Biochemistry Department, St James's University Hospital, Leeds using an Advia Centaur sandwich immunoassay (Siemens, Camberley, UK). Regression coefficients (CA-125r) were calculated with exponential regression analysis in SPSS using all the CA-125 levels from time of starting NAC (including up to 5 days before the start of chemotherapy) until CA-125 normalization, or day of IDS. Example regression curves for patients with a high, average and low CA-125 regression coefficients are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Regression kinetics for CA-125.

A CA-125 values against time for 3 patients with good, average and poor CA-125 response to NAC B Regression curves plotting CA-125 (y-axis (log-scale)) against time (x-axis) from starting NAC C Regression co-efficients

Results

In total, 63 women fulfilling the above criteria were identified. Their characteristics are presented in Table 1. The median length of follow up from commencing NAC was 31.8 months (range 4.9 – 55.1 months).

Table 1. Patient Characteristics.

| Characteristic | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 63 | 100 |

|

| ||

| Age (years) | ||

| Median (range) | 64 (32-86) | |

|

| ||

| Primary Site | ||

| Ovarian | 42 | 66.6 |

| Primary Peritoneal Carcinoma | 21 | 33.3 |

|

| ||

| Morphology | ||

| Serous | 52 | 82.5 |

| Endometrioid | 2 | 3.2 |

| Clear Cell | 3 | 4.7 |

| Mixed Mullerian Tumour | 2 | 3.2 |

| Missing | 4 | 6.4 |

|

| ||

| FIGO Stage | ||

| III | 47 | 74.6 |

| IV | 16 | 25.4 |

|

| ||

| WHO Performance Status (at baseline) | ||

| 0 | 5 | 7.9 |

| 1 | 32 | 50.8 |

| 2 | 20 | 31.7 |

| 3 | 6 | 9.5 |

|

| ||

| Grade | ||

| 1 | 8 | 12.7 |

| 2 | 20 | 31.7 |

| 3 | 24 | 38.1 |

| Missing | 11 | 17.5 |

|

| ||

| Serum Albumin (g/l) | ||

| At Presentation - median (range) | 38 (23-47) | |

| Prior to IDS – median (range) | 43 (23-48) | |

|

| ||

| Indication for IDS approach | ||

| Extent of disease | 33 | 52.4 |

| High risk surgical candidate | 4 | 6.3 |

| Extent of disease and high risk | 10 | 15.9 |

| Lack of surgical theatre time | 3 | 4.8 |

| Trial participation (CHORUS) | 5 | 7.9 |

| Patient preference | 4 | 6.3 |

| Unknown | 4 | 6.3 |

|

| ||

| Cytoreduction at IDS | ||

| Optimal (≤1 cm residual) | 43 | 68.3 |

| Suboptimal (>1 cm residual) | 20 | 31.7 |

|

| ||

| Pre-operative chemotherapy (no.of cycles) | ||

| 3 | 51 | 80.9 |

| 4 | 9 | 14.3 |

| 5 | 1 | 1.6 |

| 6 | 2 | 3.2 |

In each case, the decision to adopt a neoadjuvant treatment approach was made at a Multidisciplinary Team (MDT) meeting. Overall (Table 1), 14 (22%) women were considered unfit for primary surgery (in terms of surgical risk). 8 (13%) of the 63 patients had initial laparotomy with little or no tumor debulking.

Seventeen (27%) women received single agent carboplatin in both the neoadjuvant and postoperative phase. Five (8%) women received carboplatin preoperatively which was changed to a taxane containing regimen postoperatively: paclitaxel and gemcitabine 3; paclitaxel and carboplatin 1; docetaxel and carboplatin 1. 41 (65%) women commenced neoadjuvant combination carboplatin and paclitaxel chemotherapy. Of these 41 patients, one required a change to single agent carboplatin preoperatively and five postoperatively due to paclitaxel-related toxicity.

The number of cycles of chemotherapy patients received pre-operatively is shown in Table 1. Overall (pre- and post-operative chemotherapy combined), 51 (81%) women received six cycles of chemotherapy, 1 (2%) four cycles, 3 (4%) five cycles, 2 (3%) seven cycles, 5 (8%) eight cycles and 1 (2%) nine cycles.

Normalization of CA-125 (<35 IU/ml) prior to IDS and on completion of post-surgical chemotherapy was observed in 15 (24%) and 49 (78%) of patients respectively. In the preoperative phase, 60 women had between two and seven CA-125 measurements (median=3). Three women had only one preoperative CA-125 measurement and were excluded from tumor marker kinetics analysis.

The CA-125 preoperative regression coefficient CA-125r ranged from −0.119 (max regression) (corresponding to a CA-125 half life of 5.82 days) to −0.01 (corresponding to a CA-125 half life of 69.3 days). One patient had a positive CA-125r (0.001) and essentially static CA-125 (Table 2).

Table 2. CA-125 regression and corresponding half-lives considered as tertiles.

Shaded figures refer to patients illustrated in Figure 1.

| Lowest Tertile | Medium Tertile | Highest Tertile | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CA-125r | CA-125 T1/2 (days) |

CA-125r | CA-125 T1/2 (days) |

CA-125r | CA-125 T1/2 (days) |

||

| −0.119 | 5.82 | −0.059 | 11.75 | −0.038 | 18.24 | ||

| −0.109 | 6.36 | −0.055 | 12.60 | −0.037 | 18.73 | ||

| −0.104 | 6.66 | −0.055 | 12.60 | −0.035 | 19.80 | ||

| −0.102 | 6.79 | −0.054 | 12.83 | −0.034 | 20.38 | ||

| −0.099 | 7.00 | −0.054 | 12.83 | −0.034 | 20.38 | ||

| −0.097 | 7.14 | −0.053 | 13.08 | −0.032 | 21.66 | ||

| −0.092 | 7.53 | −0.052 | 13.33 | −0.028 | 24.75 | ||

| −0.082 | 8.45 | −0.051 | 13.59 | −0.028 | 24.75 | ||

| −0.081 | 8.56 | −0.049 | 14.14 | −0.025 | 27.72 | ||

| −0.074 | 9.36 | −0.049 | 14.14 | −0.024 | 28.88 | ||

| −0.073 | 9.49 | −0.048 | 14.44 | −0.02 | 34.65 | ||

| −0.071 | 9.76 | −0.048 | 14.44 | −0.017 | 40.76 | ||

| −0.068 | 10.19 | −0.048 | 14.44 | −0.016 | 43.31 | ||

| −0.065 | 10.66 | −0.048 | 14.44 | −0.015 | 46.20 | ||

| −0.064 | 10.83 | −0.046 | 15.07 | −0.015 | 46.20 | ||

| −0.064 | 10.83 | −0.044 | 15.75 | −0.015 | 46.20 | ||

| −0.063 | 11.00 | −0.044 | 15.75 | −0.014 | 49.50 | ||

| −0.062 | 11.18 | −0.044 | 15.75 | −0.011 | 63.00 | ||

| −0.061 | 11.36 | −0.041 | 16.90 | −0.01 | 69.30 | ||

| −0.059 | 11.75 | −0.039 | 17.77 | 0.001 | −693.00 | ||

Twenty one women (33.3%) underwent paracentesis during, or within 14 days of starting, NAC.

Univariate Analysis

On univariate analysis, factors significantly (p<0.05) associated with TTS and TTC were degree of cytoreduction at IDS and CA-125r, when considered both in tertiles and as a continuous variable. Pre-IDS albumin, degree of cytoreduction at IDS and CA-125r were associated with OS (Table 3).

Table 3. Univariate analysis.

Significant variables and those considered within the multivariable model are presented. No evidence of violation of the proportional hazards assumption was found in any models (p>0.05 Grambsch Therneau test)

| Time to CA-125 progression | Time to 2nd line | Overall Survival | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Characteristic | HR | 95% CI | p-value | HR | 95% CI | p-value | HR | 95% CI | p-value |

| Age | 1.011 | (0.987, 1.037) | 0.367 | 1.013 | (0.988, 1.039) | 0.302 | 1.021 | (0.989, 1.055) | 0.208 |

|

| |||||||||

| Stage | |||||||||

| 4 vs. 3 | 1.454 | (0.811, 2.605) | 0.209 | 1.444 | (0.795, 2.625) | 0.228 | 1.918 | (0.925, 3.976) | 0.08 |

|

| |||||||||

| Grade | |||||||||

| Grade 2 vs. 1 | 0.726 | (0.297, 1.771) | 0.481 | 0.753 | (0.294, 1.93) | 0.554 | 0.566 | (0.186, 1.721) | 0.316 |

| Grade 3 vs. 1 | 1.276 | (0.537, 3.032) | 0.581 | 1.404 | (0.564, 3.494) | 0.466 | 1.138 | (0.415, 3.119) | 0.802 |

| Grade 3+2 vs. 1 | 1.617 | (0.893, 2.926) | 0.112 | 1.741 | (0.958, 3.165) | 0.069 | 1.692 | (0.827, 3.459) | 0.150 |

|

| |||||||||

| Pre-IDS Albumin (g/l) |

0.496 | (0.119, 2.065) | 0.336 | 0.357 | (0.09, 1.411) | 0.142 | 0.199 | (0.043, 0.917) | 0.038 |

|

| |||||||||

| Cytoreduction | |||||||||

| >1cm vs. ≤1cm | 2.050 | (1.153, 3.645) | 0.014 | 2.331 | (1.310, 4.149) | 0.004 | 2.374 | (1.173, 4.807) | 0.016 |

|

| |||||||||

| CA-125r (as tertiles) (lowest vs. highest) |

2.575 | (1.2974-5.111) | 0.007 | 2.860 | (1.403-5.832) | 0.004 | 3.337 | (1.246-8.938) | 0.017 |

|

| |||||||||

| CA-125r (continuous variable) |

1.183 | (1.069, 1.310) | 0.001 | 1.180 | (1.07, 1.303) | 0.001 | 1.203 | (1.049, 1.379) | 0.008 |

Multivariable analysis

When considering all variables within the multivariable model for OS, no factors were independently prognostic. However, when degree of cytoreduction was removed from the model (since it is an unknown variable prior to surgery), CA-125r was the only factor predictive of OS [HR 1.18 (per 0.01 increase in CA-125r), 95% CI 1.01-1.40, p = 0.043] (Table 4). In other words, when considering the extremes of CA125r within our population, the hazard of death for a woman with a CA125r of −0.01 was 12.98 times that of a woman with a CA125r of −0.119.

Table 4. Multivariable analysis.

Again, no evidence of violation of the proportional hazards assumption was found in any fitted models (p>0.05, Grambsch-Therneau test).

| Time to CA-125 progression | Time to 2nd line | Overall Survival | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Characteristic | HR | 95% CI | p-value | HR | 95% CI | p-value | HR | 95% CI | p-value |

| CA-125ra | 1.171 | (1.022, 1.341) | 0.032 | 1.171 | (1.020, 1.345) | 0.025 | 1.103 | (0.912, 1.304) | 0.275 |

|

| |||||||||

| Age | 1.013 | (0.983, 1.045) | 0.389 | 1.015 | (0.985, 1.046) | 0.335 | 1.036 | (0.994, 1.078) | 0.077 |

|

| |||||||||

| Cytoreduction | |||||||||

| >1cm vs. ≤1cm | 1.081 | (0.481, 2.325) | 0.890 | 1.181 | (0.532,2.619) | 0.683 | 1.978 | (0.792, 4.926) | 0.143 |

|

| |||||||||

| Stage | |||||||||

| 4 vs. 3 | 1.376 | (0.658, 2.878) | 0.396 | 1.414 | (0.657, 3.043) | 0.376 | 1.783 | (0.728, 4.369) | 0.206 |

|

| |||||||||

| Grade | |||||||||

| Grade 2 vs. 1 | 0.524 | (0.159, 1.727) | 0.288 | 0.480 | (0.142, 1.624) | 0.238 | 0.453 | (0.113, 1.808) | 0.262 |

| Grade 3 vs. 1 | 1.055 | (0.373, 2.982) | 0.919 | 1.070 | (0.363, 3.158) | 0.903 | 1.228 | (0.381, 3.958) | 0.731 |

When degree of cytoreduction not considered within multivariable model, CA-125r becomes independently significant for OS [HR1.177, 95% CI 1.005-1.379, p = 0.043)

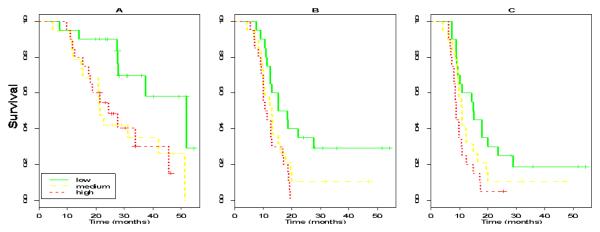

Kaplan-Meier curves for OS based on CA-125r considered as tertiles (low, medium and high) are shown in Figure 2A. Women in the lowest tertile had a CA-125 half-life of less than 11.8 days, the medium tertile had a CA-125 half-life of between 11.8 and 17.9 days and the highest tertile had a half-life of greater than 17.9 days. Median OS at 3 years in patients with low, medium and high CA-125r (equivalent to short, average and long CA-125 half-life) was 52.7 months, 21.8 months and 24.8 months respectively.

Figure 2. Kaplan Meier curves based on CA-125r.

CA-125r was considered as tertiles in all cases. A Overall survival B Time to second line treatment C Time to CA-125 progression

When TTS was examined, considering all variables including degree of cytoreduction, CA-125r was the only variable with independent prognostic value [HR 1.17 (per 0.01 increase in CA-125r), 95% CI 1.02-1.35, p = 0.025). Similarly, CA-125r was the only variable with independent prognostic value for TTC [HR 1.17 (per 0.01 increase in CA-125r), 95% CI 1.02-1.34, p = 0.032]. Kaplan-Meier curves for TTS and TTC based on CA-125r considered as tertiles (low, medium and high) are shown in Figure 2B and 2C.

Ability of CA125r to predict optimal cytoreduction

ROC curve analysis demonstrated that CA-125r was strongly predictive of optimal cytoreduction (Area under the curve (AUC) 0.756; p<0.001) (not shown). CA-125r was also found to be independently predictive of optimal cytoreduction in a multiple logistic regression model (p=0.003) also containing age, stage, grade and baseline albumin.

Discussion

Despite the fact that conclusive randomized data are still awaited, NAC followed by IDS is increasingly used in the management of women with advanced ovarian or primary peritoneal carcinoma. Pre-operative chemotherapy may reduce subsequent surgical risk and / or allow maximal cytoreductive surgery, provided an adequate response to treatment is achieved. Assessment of response to NAC is thus important and, in parallel with other malignancies (e.g. breast cancer), such knowledge may allow early detection of chemoresistance and appropriate tailoring of chemotherapy regimen. This may maximize the chance of achieving macroscopic clearance of disease, a goal increasingly important with the advent of intraperitoneal chemotherapy and cytostatic targeted treatments [12].

CA-125 is an established biomarker in ovarian cancer. However there is little existing data concerning CA-125 regression during neoadjuvant chemotherapy as a valid surrogate for outcome. Le and colleagues crudely defined CA-125 response during NAC as a decrease of >50% from baseline and found no significant association between response and progression-free survival [13]. The same authors subsequently examined CA-125 normalization during NAC as a predictor of survival. 17.8% and 57.8% of patients achieved CA-125 normalization prior to IDS and on completion of all primary chemotherapy respectively. However, normalization of CA-125 (i.e. <35 kU/L) was not an independent predictor of OS [14].

Tate et al. calculated CA-125 regression coefficients in a manner similar to the current study, demonstrating a correlation with survival, although analysis was limited to the univariate level. A coefficient of ≥ −0.039 was used to stratify good and poor responders and, of the 50 patients studied, 33 (66%) were classified as responders. 3-year survival was 70.5% vs. 43.3% in responders and non-responders respectively [15]. Based on these criteria, two-thirds of patients would be classified as responders in our study (CA-125 half-life <17.8 days), with equivalent 3-year survival times of 50.6% and 13.1%. The reason for our poorer outcomes is uncertain but may reflect the often high-risk / poor performance status indication for IDS in our population.

Unlike previous studies, we have gone on to demonstrate the independent predictive and prognostic value of CA-125r on multivariate analysis. When considering time to second line chemotherapy and time to CA-125 progression, CA-125r is a strong and independent prognostic marker, even when considering the degree of cytoreduction subsequently achieved at surgery. CA-125r is also independently prognostic for OS when the degree of cytoreduction is not considered, which is a valid omission given that, prior to surgery, the degree of cytoreduction is unknown. Women with a CA-125 half-life of less than 11.8 days had median OS more than double (52.7 vs. 23.3 months) that of women with longer half-lives. The best responders in this study had half-lives approaching the the natural half-life of CA-125, thought to be in the region of five days [16].

In addition, our data suggest that CA-125 regression and degree of cytoreduction subsequently achieved are strongly interdependent. In other words, a high CA-125r was strongly predictive of optimal cytoreduction at IDS. The obvious drawback to determination of CA-125r is that it requires more than one marker reading and mathematical calculation. A more attractive option would be the use of an absolute pre-operative level and a CA-125 of 500 IU/ml has recently been correlated with optimal cytoreduction (ROC AUC of 0.89) [8]. However this has not been replicated by others [9]. We also considered whether a CA-125 response based on GCIG criteria [17] (excluding 28 day confirmation) would be a more simple way of predicting surgical outcome. However, of the 60 women assessable by such criteria, all but three would have been deemed to have responded, thus negating its value. Furthermore, despite the widespread use of computed tomography (CT) and the development of predictive radiological models, the accuracy of predicting optimal surgery remains limited (18). Combining CA-125 regression with radiological data may increase the accuracy of predicting surgical outcome.

We found a significant association between pre-IDS serum albumin and overall survival in this study. Serum albumin is known to have prognostic value in women with conventionally treated ovarian cancer [19]. The lack of prognostic value of low baseline albumin in this study suggests that, firstly, NAC may ‘rescue’ some of these women and, secondly, that a persistently low serum albumin, despite NAC, is perhaps a more important predictor of outcome in this group of patients.

This study clearly has limitations, primarily related to its retrospective nature. The number of CA-125 measurements available in each patient was variable and may have been influenced by the observed response. A third of women underwent paracentesis during or shortly before NAC, the influence of which on serum CA-125 levels remains uncertain. We have also not examined those patients originally planned for IDS but who, following NAC, did not proceed to surgery, either due to excellent response to chemotherapy or lack of response / progression.

In conclusion, the current work suggests that, amongst chemotherapy responders, CA-125 regression is an important surrogate endpoint during neoadjuvant chemotherapy. A long CA-125 half-life predicts for suboptimal debulking and poor outcome. In such cases, consideration may be given to a more intense/alternative chemotherapy regimen. However, such an approach remains to be tested in a prospective way.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of Cancer Research UK and the UK Medical Research Council [G0802416]. We would also like to thank the following, who in addition to the authors, contributed to the management of patients within the study: Mr Geoff Lane and Mr Sam Saidi, Department of Gynecological Oncology, St. James's University Hospital, Leeds, UK; Dr Dawn Alison, St. James's Institute of Oncology, St. James's University Hospital, Leeds, UK.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

We declare that we have no conflict of interest

Reference List

- 1.Tangjitgamol S, Manusirivithaya S, Laopaiboon M, et al. Interval debulking surgery for advanced epithelial ovarian cancer: a Cochrane systematic review. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;112:257–264. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kang S, Nam BH. Does Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Increase Optimal Cytoreduction Rate in Advanced Ovarian Cancer? Meta-Analysis of 21 Studies. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:2315–2320. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0558-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vergote I, Trope CG, Amant F. EORTC-GCG/NCIC-CTG randomized trial comparing primary debulking surgery with neoadjuvant chemotherapy in stage IIIC-IV ovarian, fallopian tube and peritoneal cancer; Plenary presentation at the 12th Biennial meeting International Gynecologic Cancer Society IGCS; Bangkok, Thailand. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rustin GJ, Nelstrop AE, McClean P, et al. Defining response of ovarian carcinoma to initial chemotherapy according to serum CA 125. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:1545–1551. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.5.1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Riedinger JM, Eche N, Basuyau JP, et al. Prognostic value of serum CA 125 bi-exponential decrease during first line paclitaxel/platinum chemotherapy: a French multicentric study. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;109:194–198. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crawford SM, Peace J. Does the nadir CA125 concentration predict a long-term outcome after chemotherapy for carcinoma of the ovary? Ann Oncol. 2005;16:47–50. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bristow RE, Tomacruz RS, Armstrong DK, et al. Survival effect of maximal cytoreductive surgery for advanced ovarian carcinoma during the platinum era: a meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1248–1259. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.5.1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vorgias G, Iavazzo C, Savvopoulos P, et al. Can the preoperative Ca-125 level predict optimal cytoreduction in patients with advanced ovarian carcinoma? A single institution cohort study. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;112:11–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chi DS, Zivanovic O, Palayekar MJ, et al. A contemporary analysis of the ability of preoperative serum CA-125 to predict primary cytoreductive outcome in patients with advanced ovarian, tubal and peritoneal carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;112:6–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cox D. Regression Models and Life-Tables. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B-Statistical Methodology. 1972;34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rustin GJ. Use of CA-125 to assess response to new agents in ovarian cancer trials. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:187s–193s. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.01.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Armstrong DK, Bundy B, Wenzel L, et al. Intraperitoneal cisplatin and paclitaxel in ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:34–43. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Le T, Hopkins L, Faught W, et al. The lack of significance of Ca125 response in epithelial ovarian cancer patients treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy and delayed primary surgical debulking. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;105:712–715. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Le T, Faught W, Hopkins L, et al. Importance of CA125 normalization during neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by planned delayed surgical debulking in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2008;30:665–670. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)32914-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tate S, Hirai Y, Takeshima N, et al. CA125 regression during neoadjuvant chemotherapy as an independent prognostic factor for survival in patients with advanced ovarian serous adenocarcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;96:143–149. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Canney PA, Moore M, Wilkinson PM, et al. Ovarian cancer antigen CA125: a prospective clinical assessment of its role as a tumour marker. Br J Cancer. 1984;50:765–769. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1984.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rustin GJ, Quinn M, Thigpen T, et al. Re: New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors (ovarian cancer) J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:487–488. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Axtell AE, Lee MH, Bristow RE, et al. Multi-institutional reciprocal validation study of computed tomography predictors of suboptimal primary cytoreduction in patients with advanced ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:384–389. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.7800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clark TG, Stewart ME, Altman DG, et al. A prognostic model for ovarian cancer. Br J Cancer. 2001;85:944–952. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.2030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]